North-east Greece

Capital of the late Roman prefecture of Illyricum; abbreviated to Salonika during the Turkish period and up to 1927, when the original name was officially reinstated

During its glory years the state of Macedon, homeland of Alexander the Great, was entirely rural, with nothing much in the way of towns and nothing at all in the way of a capital city. The country’s rise from bit player to top dog had been incredibly rapid, in essence the work of a single king, Philip II, in a not-so-very-long reign of twenty-three years (359–336 BC). Constant campaigning meant that, even if building a worthy Hauptstadt had been on his must-do list, Philip never had the time to actually do it. And as his son Alexander left Greece as soon as he had secured the crown, this situation remained unchanged during his reign too. The end result was that, after two generations of hegemony over Greece, the nearest thing Macedon had to a political centre was whichever country palace the ruler happened to favour – the choice being between Aigai and Pella.

Not long after Alexander’s death his empire broke up, and the governors of the different provinces declared themselves kings. Macedon became the share of Alexander’s brother-in-law, Cassander. In 316 he decided to celebrate his rule by founding two new towns. One of them was a refurbishment of Potidaea, a place with a considerable history that had been destroyed during one of Philip’s wars. This was to be called Cassandreia. The other was a brand-new creation formed by merging the populations of twenty-six villages on and around the Thermaic Gulf. This he named after his wife Thessalonike. Presumably he thought Cassandreia had the better prospects, but if so he was to be (posthumously) disappointed. It was Thessaloniki that became the metropolis that Macedon had hitherto lacked.

The process took a very long time. It was only in the Roman period that Thessaloniki emerged as a place of importance, and the first person to refer to it as the metropolis of Macedonia is the geographer Strabo, at the end of the first century BC. The next step up came another 300 years later, when it became the capital of the diocese of the Moesias, a newly created group of provinces that embraced about a third of the Balkans. A few years later the emperor Galerius made it his official residence (from 305 to his death in 311). None of his successors agreed with his choice, so this particular bit of glory didn’t last, but the enhanced provincial status was confirmed when the prefect of Illyricum, the top man as regards Balkan defence, exchanged his post on the Danube for a safer life in Thessaloniki in 441. So long as the empire had a Danube frontier, Thessaloniki would retain responsibility for its central sector.

For a while it looked as if the frontier had been lost to the Huns (which was why the prefect had retreated to Thessaloniki in the first place), but after the death of their king Attila in 453, they withdrew to the Russian steppe and imperial troops were able to reoccupy the line of forts along the river. The next bout of trouble was more serious and lasted far longer. In 586, Slav tribes broke through the defences of the central sector and reached the gates of Thessaloniki itself. Moreover, these were not raiders but migrants. By 615 the entire area between the town and the Danube had been lost to the newcomers, and Thessaloniki had become a Greek-speaking island in a Slav sea. The only way of communicating with CONSTANTINOPLE was by boat.

Recovery was very slow. A land link with Constantinople was re-established in 783, but it took a further fifty years to make it safe. It was only in the tenth century that things really began to look up. The century hadn’t started well – a raid by an Arab fleet in 904 did a great deal of damage – but as the century progressed the town began to share in the general recovery experienced by the Byzantine state at this time. In 1018, when the Danube frontier was restored (for the last time), Thessaloniki seemed to have regained all the advantages it had enjoyed in the late Roman era.

The final phase of the empire’s history began with the Battle of Manzikert, a crushing Turkish victory in 1071 that immediately put the Anatolian half of the empire in jeopardy. The subsequent intervention of the Latin West, in the form of the Crusades, brought turbulent times for the European provinces too. Thessaloniki was sacked by the Normans in 1185 and actually became the capital of a Crusader mini-kingdom in 1204. This was replaced by a Byzantine equivalent, the empire of Thessaloniki, in 1224, before the final reincorporation of the town into the Byzantine Empire in 1246. In the interim the Danube provinces had been taken by the Bulgars, starting in 1186. All this sounds like bad news, as indeed some of it was, but there was an upside. In the wake of the first Crusaders came the Venetians and Genoese, eager for trade and offering new markets. So long as Thessaloniki had a hinterland, it could enjoy the benefits brought by the increase in Aegean traffic. The record of its buildings suggests that it did, that the thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries were Christian Thessaloniki’s Indian summer, and that it was only with the loss of the hinterland, first to the Bulgars, then to the Turks, that decline set in. The city fell to the Turks in 1387, briefly returned to Byzantine rule in the aftermath of the Battle of Ankara in 1402, before its definitive incorporation in the Ottoman Empire in 1430. It remained under Turkish rule until 1912.

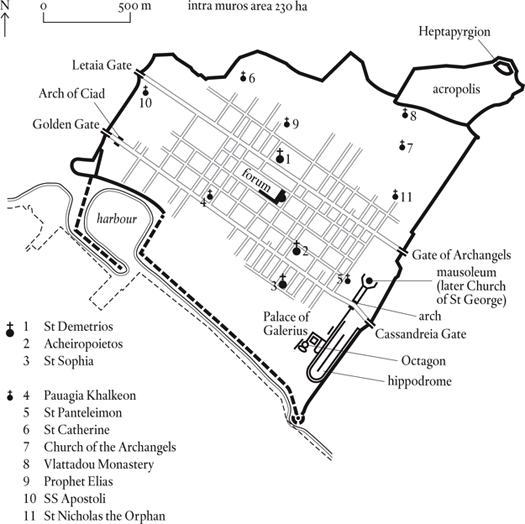

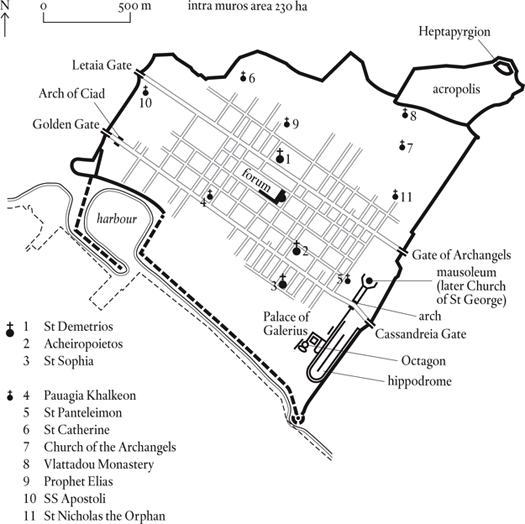

As is the case with many Greek coastal settlements, Thessaloniki consisted of a lower town where the people lived, and an acropolis some way inland, which acted as a citadel of last resort. Thessaloniki’s lower town was laid out as a rectangular grid of streets and avenues, half a dozen or more avenues parallel with the shore, and more than two dozen cross-streets (a surviving inscription gives an address on 18th Street). Remarkably, much of the grid is still visible in the present-day street plan, a testimony to 2,300 years of continuous habitation. The land walls too, even if much rebuilt, seem to have kept close to the original trace, although at two points there is clear evidence that they had moved out a bit: the early Roman version of the Golden Gate ended up well inside the final version (it was left as a free-standing arch), and, on the opposite side of town, the walls take a jog around the north end of Galerius’ palace. Most of the northern half of the circuit survives: the walls and towers of this part are basically late Roman work, although there are some towers with Palaeologan (late Byzantine) inscriptions in and around the acropolis, and other elements are obviously Turkish. The line of the sea wall is unknown, and the reconstruction of this and the harbour works attributed to Constantine the Great is purely hypothetical. Trial excavations in this area could be very rewarding.

The two main building complexes surviving from the Roman period are the forum, of which a corner is visible in the centre of town, and the Palace of Galerius in the south. The palace was preceded by a monumental arch commemorating Galerius’ victories over the Persians; north of it was a circular building presumably intended as his mausoleum. Half the arch survives, as does the mausoleum, which by the fifth century had become the Church of St George – ironical considering that Galerius was a determined opponent of Christianity. Other parts of the palace survive as foundations, as does the outline of the hippodrome, a must-have add-on for an imperial palace of this period.

Aside from these public monuments of the imperial era, Thessaloniki is known for its many churches. The three most remarkable are the Acheiropoietos of the mid fifth century, St Demetrios, a seventh-century replacement of a fifth-century original, and St Sophia, built some time between the late sixth and the early eighth centuries. After a long gap, church building resumed in the late Byzantine period; half a dozen churches, most of them rather small, represent the final flourish of Christian Thessaloniki. All these churches, early Christian and Palaeologan alike, ended up as mosques following the Turkish conquest of 1430.

The first firm evidence we have for the size of Thessaloniki’s population is an Ottoman census of households from 1478. This shows that the town was still more Christian than Muslim at the time – 1,275 Christian households and 826 Muslim. By 1519 the two communities were equal in size (1,387, compared to 1,374), and both were overshadowed by a Jewish community of 3,143 households. Although the Jewish community was swollen by refugees expelled from Spain in 1492, it must already have been in existence in 1478 (indeed, Benjamin of Tudela says the town had 500 Jews in the twelfth century), so the early account needs upward adjustment. If we assume something of the order of 1,000 Jewish households in 1478, the total population for this date will be 1,275 + 826 + 1,000 = 3,101 × 4 = 12,404, say 12,000, compared to 1,387 + 1,374 + 3,143 = 5,904 × 4 = 23,616, say 24,000 in 1519. Interpolating gives us a total population of 18,000 for 1500, and back-projecting suggests that the population is more likely to have been under than over 10,000 in 1450. This fits with the fact that the number of captives taken by the Ottoman sultan Murad II when the town surrendered to him in 1430 was only 7,000.

On this basis it seems reasonable to take 10,000 to 15,000 as the range of Thessaloniki’s population in its prosperous phases. There seem to have been two of these: the first beginning with the town’s brief prominence as a tetrarchical capital in AD 305 and ending with the loss of its hinterland to the Slavs in the early seventh century; the second beginning with the late tenth-century recovery of the Byzantine Empire and lasting until the empire’s collapse in the early fifteenth century. To be conservative, we can credit Thessaloniki with a population of 10,000 in the period AD 350–600 and again in AD 1000–1400. If you are an optimist you could raise some or all of these figures to 15,000. The final figure of 18,000 is the only one that is entirely secure.