Indre-et-Loire, France

Classical Caesarodunum Turinorum

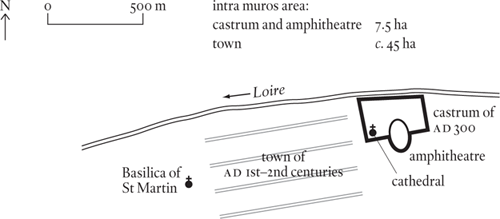

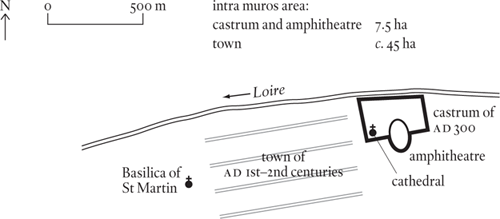

Roman Tours was built, apparently on a greenfield site, as a county town for the local Celtic tribe, the Turini. Work probably started in the reign of Augustus (27 BC–AD 14), with the planners laying out a street plan of the usual gridded type on the south bank of the Loire, and the authorities cajoling the better-off Turini into building themselves houses there. The grid probably covered around forty-five hectares and the built-up area forty hectares by the second century AD when the town acquired its sole surviving monument, a massive amphitheatre. This was situated at the eastern end of town and, truth to tell, all we know of the town is that it occupied the area between the amphitheatre in the east and a cemetery in the west; all the rest – the grid, its extent, and the extent of the built-up area – are suppositions with almost no archaeology to back them up.

Such prosperity as Roman Tours had enjoyed in the first century began to ebb away in the second, well in advance of the third-century invasions that were to bring more drastic sorts of trouble. With the fourth century came two important consolations: Tours was made the administrative centre of one of the new small-sized provinces, Lugdunensis III, and in consequence of this promotion it became the seat of an archbishop. When the governor arrived, he probably found the town in ruins; more certainly he found what was left indefensible, for there is no evidence that early Roman Tours had ever been walled. His solution was to fortify the amphitheatre and a small area around it and concentrate what was left of the population in this castrum. The enclosed area was tiny, amounting to no more than 7.5 hectares. The archbishop built his cathedral – the predecessor of the current Cathedral St-Gatien – in the south-west quarter of the castrum, and there is no sign of urban life continuing outside of it. Late Roman Tours was not really a town in any meaningful sense of the word.

It was against this unpromising background that Tours acquired its first measure of fame. This came in the form of St Martin, archbishop of Tours in the last days of the empire, a great enemy of pagans and the founder of many churches and monasteries. When he died in AD 397 he was buried in the old western cemetery, which subsequently became a hallowed spot. By 470, St Martin’s reputation as a miracle worker – even in death – was attracting so many pilgrims that the church authorities built a basilica over his tomb. As the Roman Empire crumbled away, other buildings were added, including an abbey, and eventually, in 918, after the Normans had burned down the original basilica, the complex was given its own defensive wall. Medieval Tours consisted of two physically distinct mini-towns: the settlement around the basilica of St Martin (‘Châteauneuf’), and the old Roman castrum a kilometre (0.6 miles) to the east. Of the two it was Châteauneuf that was to prove the more dynamic.

Roman Tours is unlikely to have held more than a couple of thousand people at best; in its final form it was too small for more than a few hundred.