Yorkshire, England

Classical Eboracum, capital of the Roman province of Britannia Inferior; diocese: Britain

York was originally built as a legionary fortress by IX Hispana in AD 71. The legion, which had previously been stationed at LINCOLN, provided the spearhead for the Roman advance into northern Britain on the route east of the Pennines. It kept York as its base until early in the second century when it was transferred to the continent before mysteriously disappearing from the Roman army list – maybe annihilated, more probably cashiered following a culpable defeat. Its place at York was taken by VI Victrix, which arrived in Britain from Germany in AD 122. This legion was to remain at York as long as the empire lasted.

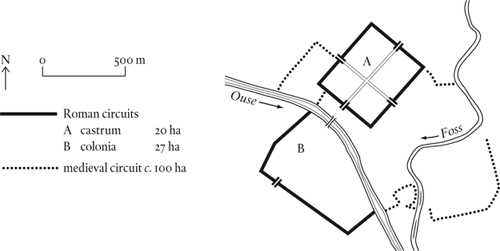

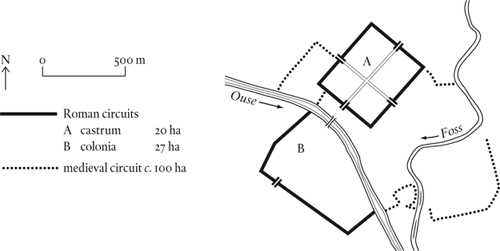

The twenty-hectare legionary fortress of York lies on the north bank of the River Ouse. A civilian settlement soon grew up on the opposite bank, and this ultimately received official recognition as a Roman colony. The promotion may well have been linked to another cause, the choice of York as the capital of North Britain (Britannia Inferior) when the province of Britain was divided in two by Caracalla (AD 211–17).

Roman York now entered its most prosperous phase. The legionary garrison was at its full strength of 5,000 or so, there were something like 2,000 civilians in the walled (27-hectare) town on the opposite bank, plus another 1,000 in the shanty town surrounding the legionary fortress, a total of around 8,000. It seems unlikely that York ever exceeded a population of 10,000, because it remained what it had been from the start, a garrison town. It can, however, claim the title of ROME’s northernmost town of significant size.

Little remains of York’s Roman glories. On the south side of the Ouse there is nothing at all to see; on the north bank there are some stretches of the fortress wall, and the corner tower on the west, referred to in travel literature as the ‘Multangular Tower’. More interesting are the remains of the legionary headquarters building under the cathedral crossing. The amphitheatre has not been found as yet.

The mid third century AD will have marked the peak of York’s Roman prosperity. In the fourth century the strength of the garrison will have halved and halved again in line with the reduction in the size of the legions that took place throughout the empire. Similarly, the governor’s entourage will have been cut when Britannia Inferior was divided into two, maybe three, smaller provinces. And population trends were down anyway. As an urban unit, Roman York was already dying when the fifth century opened. By the sixth century both the castrum and the colony were deserted.

If York was in ruins in the seventh century, the Catholic Church had not forgotten its previous status, and when the opportunity for a missionary enterprise in the north presented itself, York was given a starter bishop. In 735 the see was elevated to an archbishopric, making it the second most senior ecclesiastical post in the land. As such it was an obvious target for the Vikings when, 100 years later, they began laying the foundations of a kingdom covering the northern half of Britain. York became a capital again, this time of a Scandinavian state standing in opposition to the Anglo-Saxon (English) kingdom of Wessex in the south. It fell to the English in 954, then, after a severe harrying, to William the Conqueror in 1068–9. The Domesday survey indicates a population in the 4,000 to 5,000 range in 1086 (while suggesting it had been nearer 8,000 twenty years earlier). This figure had risen to 14,000 in the fourteenth century when the newly built wall enclosed something over 100 hectares (compared to the two Roman perimeters’ total of forty-seven hectares, a figure that could be raised to sixty hectares if the unwalled civilian settlements on the north bank are included).