CHAPTER 1

Why I Care

Plus ADD Throughout the Life Cycle

I often tell people I know more about ADD than I want to. I have not only studied ADD from the perspective of a clinician and researcher, I have lived with it at home. My first wife, Robbin, and my current wife, Tana, both have ADD. What can I say, I love exciting women. Also, several of my own children have ADD as well. For years I lived with the guilt that is often associated with having a family member who has this disorder. I thought that I was a terrible husband and a terrible father. These feelings were compounded by the fact that I was a psychiatrist and that I “should” have a perfect marriage and I “should” have well-behaved children. Things “should” have been better than they were. My son, Antony, used to joke that our family was like the cartoon Simpson family poster that read, “Okay, everybody, let’s pretend that we’re a nice, normal family” as they were getting ready to take a family picture. It was not until my children were diagnosed and treated properly that the clouds of guilt began to give way to understanding. I know this disorder from the inside out. I know what it is like:

- to have trouble holding a small child because she is in nonstop motion

- to chase a child through the store

- to chase a four-year-old child who is darting across a busy parking lot, all the while imaging her being struck by a car, which gratefully never happened, but I have the emotional scars from the visual images

- to watch a child take four hours to do twenty minutes of homework

- to watch a child stare at a writing assignment for hours, unable to get thoughts from his brain to the paper

- to go to teachers’ conferences where my child has been described as bright, spacey, and underachieving

- to have to repeat myself thirty-two times to get a child up in the morning

- to be asked for help at 11:00 P.M. the night before a term paper was due when the child knew about it for four weeks!

- to be angry every school morning for years because a child is continually ten minutes late

- to be amazed that a child’s room can become so messy in such a short period of time

- to be always on alert in a store or at a friend’s house so that my child won’t touch or break something

- to be frustrated by trying to teach a child something, only to have him or her continually be distracted by something irrelevant

- to feel guilty about the negative feelings I have toward a child after I’ve told him or her not to do something for the umpteenth time

- to be embarrassed to the point of madness by a child’s behavior in a restaurant (and wonder why I’m spending money to suffer)

- to be interrupted without mercy while I’m on the telephone

- to live through angry outbursts that have little or no provocation

My adopted son Antony was diagnosed with ADD when he was twelve years old. His biological father, Jim, was described as someone who never sat still, was impulsive, and had to be chained to his chair to get his homework done. It was only through the patience and diligence of Jim’s mother, that Jim even finished high school. Like many ADD adults, Jim thrived in the military, as a Marine military police officer. The structure seemed to be very helpful for him. But after the service Jim struggled in all areas of his life. He had several marriages, many jobs, trouble with alcohol, and in his thirties, he shot and killed himself. I was able to adopt Antony when he was three years old. I married his mother, Robbin, who had once been married to Jim. I could adopt Antony even though Jim was alive at the time because Jim never paid child support. In Oklahoma, where I was in medical school, there was a law that if a parent did not live up to their obligation, the stepparent could adopt the child.

I adored Antony, but his room used to follow the second law of physics, meaning that things went from order to disorder. I used to ask him if he planned to have his room that messy. His handwriting was a mess and a half an hour of homework used to take him three hours to do, with his mother yelling at him to sit down and get it done. Antony’s school performance alternated from being excellent if he loved his teacher, to mediocre, despite having a high IQ. As part of a study I was doing on ADD with an electrical brain imaging study called quantitative EEG, I scanned Antony’s brain. His scan pattern was clearly consistent with ADD. He had an excessive amount of slow brain wave activity in the front part of his brain. When I saw the results it made perfect sense to me.

On the surface, Breanne, my oldest daughter, was the perfect child. She was always easy, always sweet, her room was always clean and her homework always done. If I only had Breanne I would have been a terrible child psychiatrist. I would have thought Breanne was so wonderful because I was such a good dad. If I saw your child acting up in the grocery store, I would have thought to myself “give me your child for a week and I will straighten him out and then teach you how to be a good parent.” Well God knew I was like that, so God gave me Kaitlyn.

Hyperactive from before birth, we thought Kaitlyn was going to be a boy, because the lore is that the more active babies are inside their mother’s womb the more likely they are to be boys. Well she wasn’t. Trying to hold Kaitlyn when she was a year old was like trying to hold a live salmon. I had a spiritual crisis because of this child. Many Catholic churches have the tradition of young children sitting with their parents at mass. It was no fun with Kaitlyn, because she was the worst-behaved child at church, which was not only embarrassing, it was bad for business. I treated half the children in the congregation and if my child was the worst one, people would lose confidence in me. So after a while I stopped going to church.

Have you ever seen children on little yellow leashes in the mall? After having Kaitlyn I believed in little yellow leashes because she was always trying to get away. But my problem was that I wrote a column in the Daily Republic, a local newspaper where I lived, and whenever I went to the mall people recognized me and said things like, “Hey, you’re Dr. Amen! I loved your column.” I just could not deal with, “Hey, you’re Dr. Amen! Why is your child on a leash?” So what I used to do with Kaitlyn was put her in her stroller and tie her shoelaces together so she couldn’t get out. Now, I am not proud of that but when you have a hyperactive child you do things just to survive.

When Katie was three years old I went back to church, but left her at home. I went to pray for a healing. I believe in healings. At the time I knew that 30 percent of three-year-olds look hyperactive, while only 5 to 10 percent of four-year-olds are hyperactive. So the first time you can really diagnose ADD with confidence is about four years old. I lit candles at church, and even put an extra fifty dollars in the offering, trying to bribe God. I wrote to the Pope and asked him to send a blessed picture that I could put by her bed. But he must have had a secretary with ADD because no one wrote me back. At the age of four years old I brought Katie to a colleague who diagnosed her with ADD.

During Kaitlyn’s evaluation the psychologist looked at Robbin, and then at me and basically asked us who had it. As we will see, ADD usually runs in families. Obviously, it couldn’t be me, I thought, except I do have an older brother who was hyperactive as a child and did not do well in school. But those issues were never mine. I tended to be anxious, on time, and focused. The answer came when our doctor asked Robbin how she studied. At the time Robbin was slowly finishing her bachelor’s degree. Robbin said she could never study at home; there were too many distractions. She would get into her car and park underneath a street-lamp, where there were no kids, no noise, nothing, then she could study. When Robbin was diagnosed with ADD, a new world of hope and understanding happened between us. The treatment for ADD significantly helped Kaitlyn too.

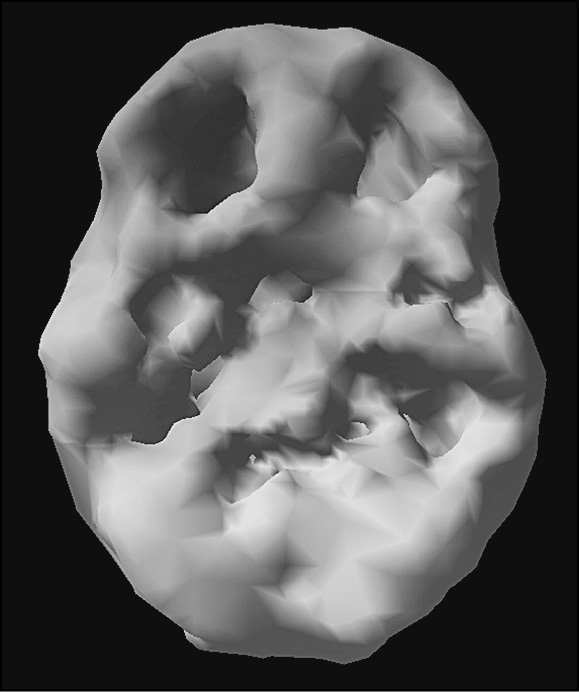

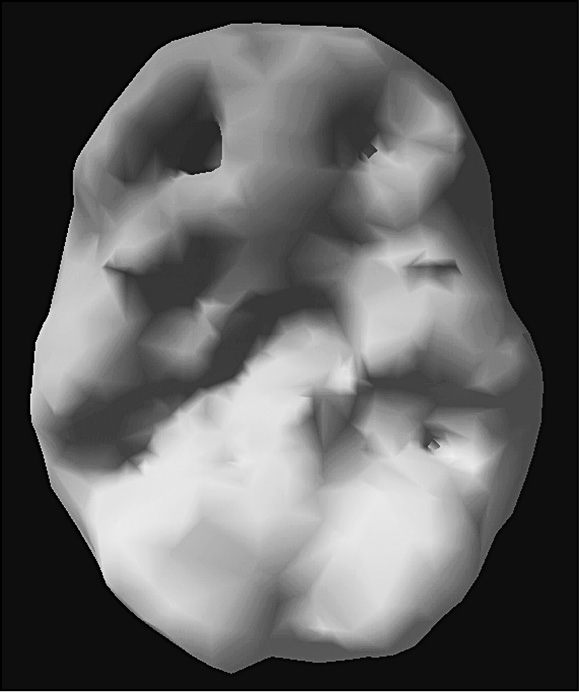

Even though Breanne was the perfect child, the truth is I never thought she was very smart. It hurts me to say that, but that was how I felt. I had to teach her simple things over and over and she did not learn her times tables until she was in fifth grade. I had her tested by a psychologist in the third grade who basically told me the same thing: she wasn’t that smart. She didn’t say it that way, but I could read between the lines. But the psychologist said Breanne would be okay because she worked so hard. In fact, in eighth grade Breanne won a presidential scholar award, not for academics but for effort. In tenth grade, however, things started to fall apart. She was in a college prep school and stayed up every night until one or two o’clock in the morning to get her homework done. Then one night, while studying genetics in biology, she came to me confused and in tears and said she thought she could never be as smart as her friends. It broke my heart. The next day I pulled up her brain scan that I had done when she was eight years old. When I first started to do brain SPECT scans in 1991 I scanned everyone I knew. I had scanned my three kids, my mother, even myself. At the time I only had the experience of someone who had seen fifty scans. Now, seven years later, I had seen thousands of scans. With experienced eyes I was horrified by what I saw. Breanne had low overall activity, especially in the front part of her brain.

I came home that night and told Breanne what I saw and told her I wanted to get a new set of scans. Because of the injection of a radiopharmaceutical that is necessary for the SPECT scan, she protested, “I don’t want a scan, Dad. All you think about are scans.” But I am a child psychiatrist. I know how to get my way with kids. I felt this was very important and so I asked her what it would take to get her to agree to a scan. She told me she wanted a telephone line in her room. I started to think that maybe she was smarter than I thought. Well, her new SPECT studies were virtually identical to the ones seven years earlier. I cried when I saw them.

I put her on a low dose of medication, and the next night I rescanned her. Her brain normalized. Breanne’s learning struggles had nothing to do with her intelligence. The low activity in her brain was limiting the access she had to her own brain. I had her continue with the low dose of medicine along with some supplements. A week later Breanne and I went to dinner together. She said learning was much easier for her. In fact, she said, “I think I am going to be a geneticist. I can see the DNA molecule rotate in my head. Don’t you think it’s the future, Dad?” I was floored. Three months later, Breanne brought home straight A’s. These were the first A’s of her life. Over spring break that year I was invited to Israel to speak to an International ADD Conference. I took Breanne with me. On the plane I saw Breanne do schoolwork for eight straight hours. I leaned over to her and asked, “So what do you think the difference is, being treated for ADD?” What she said was so telling.

Breanne’s Concentration SPECT Study Before and After Treatment (Underside Surface View)

Improved activity

“I used to hate school, Dad, because I had trouble learning. A one hour class seemed like it went on all day long. It was painful. Now, I can pay attention, and that same class seems like it goes by in twenty minutes and I love it because I can do it.” That statement is critical. Many kids and adults hate school and learning because it is hard, and no one likes feeling incompetent.

Breanne went on to say, “I used to be very religious in school.”

“What does that mean?” I asked.

“After ten minutes I was so lost in class that I would pray to God that the teacher would not call on me, because I had no idea what was going on. Now, I can track things and learning is much easier.” She said she now understood concepts of biology for the first time. Usually a shy child in class, she started raising her hand and even participated in debates. At dinner one night she winked at me and said, “I kicked butt in a debate today, Dad.” This was not the same child I knew. She had a completely different perception of herself—one that fit the reality of her being smart, competent, and able to look forward to a bright future.

Even though I had heard these stories from my patients for many years, it was something else to hear it from my own daughter. Through the rest of high school and college, Breanne got straight A’s, and was accepted to one of the best veterinarian schools in the world at the University of Edinburgh. Even though Breanne decided not to go, because she had just given birth to her first child, she knew she was good enough to be accepted, which made all the difference in how she thought about herself.

Whenever I tell Breanne’s story at lectures many women come up to me afterwards with tears in their eyes and tell me that they can relate to her. If only they knew, how life would have been different for them. My comment to them is, “You cannot change the past, but you can certainly start where you are now and work hard to change the future.” I want your future to be the best it can be, no matter where you start from.

As we will see, ADD has deep genetic roots. When Kaitlyn had my grandson Liam, he so reminded me of her. Trying to hold him was like holding a live salmon. He is sweet, but very busy. And the ADD activity and beat go on.

I have used the principles in this book to guide the treatment of my patients and to help my own family. I know this information will help you.

ADD THROUGHOUT THE LIFE CYCLE

One of the best ways to diagnose ADD is to understand a detailed history of a person’s life. Here’s a look at ADD throughout the life cycle. It is important to note that ADD does not just appear in the teenage years or in adulthood. When you know what to look for, you can see that ADD symptoms have been present for most of a person’s life.

Many hyperactive ADD children (Classic ADD) are noted to be overly active in the womb. One mother told me that her unborn child kicked her so hard during the eighth month of pregnancy that he broke her ninth rib! Many are also difficult from birth: A significant number are colicky, fussy eaters, have a difficult time being comforted, are sensitive to noise and touch, and have eating and sleeping difficulties. As toddlers, they’re often excessively active, mischievous, demanding, difficult to toilet train, and noncompliant with parental requests (like the terrible twos on overdrive).

Most ADD children are not recognized as such until they go to school: In kindergarten or in first or second grade, schoolteachers often notice the difference between these children and others. Teachers have a large database of expected behavior, while most parents do not. By the time they have entered school, hyperactive boys’ problems with aggression, defiance, and oppositional behavior have often emerged. These problems often lead to social isolation and poor self-esteem.

Many ADD kids have varying degrees of poor school performance related to failure to finish assigned tasks, disruptive behavior during class, and poor peer relations. The time that these problems become apparent often relates to intelligence and the school setting. Often, the brighter the child, the later he or she is diagnosed. Up until that time, the child is likely to be labeled as an underachiever, willful, defiant, or oppositional.

At one time, it was believed that ADD symptoms disappeared by puberty. However, current studies indicate that only 25 to 50 percent of ADD kids fully outgrow their symptoms by puberty. Many do not outgrow their symptoms and they have difficulty with their family, school, and/or the community. This misperception occurred in part because most ADD children outgrow the hyperactive component before or at puberty. The problems with inattention and impulsivity remain, and many teenagers are taken off their medication just at a time when their defiant behavior is at its peak. I have seen that many teens experience serious school and social failure after the pediatrician or family doctor prematurely takes them off their medication.

There is a high incidence of conflicts in ADD families, especially during the teenage years. These conflicts often center around failure to do schoolwork, problems completing routine chores, and difficulty being trusted to obey the rules. I have seen many teenagers sent away from home (to a residential treatment setting, boarding school, or relative’s house) as a way for the family to survive the turmoil.

Many adults with ADD live lives of chronic frustration. Psychiatrists Henry Mann and Stanley Greenspan wrote the first article on ADD in adults in 1977, yet the medical community was very slow to recognize ADD in adults. It has only been since the late 1980s that professionals began talking about ADD beyond the adolescent years. Still, even now many professionals do not understand ADD in adults and often describe these people as having character problems, anxiety, depression, or even manic-depressive disorder. Their childhood ADD symptoms are assumed to have just melted away. Adults with ADD often come to our clinic with the following concerns:

- Concerns about a child with ADD. Most adults with ADD are only diagnosed after they bring one of their children in for evaluation. During a thorough history, the child psychiatrists ask about family history. Through these questions the light goes on for many people.

- Poor school/work performance caused by the following symptoms: poor sustained attention span to reading, paperwork, etc.; high susceptibility to boredom by tedious material; poor organization and planning; procrastination until deadlines are imminent; restlessness, trouble staying in a confined space (not a phobia); impulsive decision making; inability to work well independently; failure to listen carefully to directions; frequent impulsive job changes; poor academic grades for ability; frequent lateness for work/appointments; or a tendency to misplace things frequently.

- Symptoms of trouble thinking clearly, generally poor self-discipline, moodiness, chronic anxiety, restlessness, substance abuse, uncontrolled anger, marital problems, sleep problems, financial problems, or impulsiveness.

ADD IN THE ELDERLY

There is also no question in my mind that ADD exists in the elderly and that it seriously handicaps many of them. I have diagnosed many elderly people with ADD, mostly after I have seen their children, grandchildren, or great-grandchildren. My oldest patient, Betty, was ninety-four when she came to see me. I had seen three generations of people in her family: her son, grandson, and great-granddaughter. When I asked her why she wanted to be evaluated, she said that she wanted to be able to finish reading the paper in the morning. ADD symptoms in the elderly cause social isolation, difficult behavior, and a higher incidence of cognitive problems. For decades geriatric psychiatrists have used medications like Ritalin to help sharpen cognitive skills. Perhaps they were, in part, treating the very high incidence of ADD in the elderly.

Watch for the Wall

Many bright children with ADD, especially Type 2 (Inattentive ADD), are not diagnosed until later in their development, if at all. They do fine for a while and then slam into failure: The Wall! Depending on intelligence, class size, and knowledge level of the parents, they may not have problems until third grade, sixth grade, ninth grade, or even college. I’ve treated some college professors who received good grades in graduate school but still had the majority of symptoms of the disorder. They state, however, that it took them four or five times the amount of time and effort to do as well as their peers.

My son, whose greatest difficulties were in the ninth grade, actually got straight A’s in the sixth grade. He said, “In sixth grade, I knew everything that the teacher was talking about. It was easy. In ninth grade, I did not know as much and I couldn’t bring myself to focus on all the material I needed to learn.”

The Wall is different for each person with ADD.

ADD STORIES THROUGH THE LIFE CYCLE

ADD may not make someone look different on the outside, but you can see it plainly when you know what to look for. The following case histories demonstrate how ADD impacts people throughout the life cycle. The names and details have been altered, as they have been throughout this book, to protect the confidentiality of my patients.

Children

ALFIE

Alfie, age ten, had trouble from the time he was very young. In preschool the teachers complained about his lack of attention, hyperactivity, and disruptive, impulsive behavior. Alfie’s work was sloppy, he frequently forgot or lost assignments, and his desk at school and his room at home were usually a mess! Alfie constantly challenged his parents, seemed to thrive on chaos and conflict, and frequently hurt himself by doing stupid things, such as jumping out of trees. He had already broken three bones. Homework was always a struggle. Work that typically took their other kids thirty minutes to finish took Alfie three or four hours to complete, with his parents having to provide constant supervision. While doing his homework, he was up every five minutes looking for food or bothering his older sister. In second grade, Alfie started to hate school and thought he was stupid, even though he tested above average. Alfie typically blamed others for his problems.

His parents were at their wits’ end and constantly talked about the problems. They alternated between blaming Alfie, blaming the “lousy” school, and blaming themselves. When Alfie was five years old, his mother took him to his family doctor because of his high activity level and difficult nature. While she was talking to the physician Alfie sat perfectly still and was polite and attentive. The doctor told Alfie’s mother, in no uncertain terms, that there was nothing the matter with the boy and that she needed parenting classes. The mother left the doctor’s office in tears because he had confirmed her worst fear: she was a defective parent who caused her son’s problems. Despite the parenting classes, the problems continued.

When he was in fifth grade, Alfie came to the Amen Clinics for an evaluation. It was clear from watching him that he had difficulty concentrating, was distractible, active, and impulsive. He scored poorly on the Conner’s Continuous Performance Test (C-CPT), a fifteen-minute test of attention. Alfie’s diet was erratic and filled with lots of sugar and artificial dyes and he got little exercise. His lab tests, including thyroid studies, zinc, and blood chemistries were all normal. Alfie had Classic ADD: He was inattentive, distractible, disorganized, hyperactive, and impulsive. I changed his diet, increased his exercise, gave him EPA omega-3 fatty acids and a brain-directed multiple vitamin, talked with the school on effective classroom management techniques, and had his parents attend a parenting group designed specifically for dealing with ADD children. We also taught Alfie some specialized biofeedback techniques. Six months into his treatment, Alfie was a different child. He was less impulsive, his attention span had increased, and he was calmer. His grades improved dramatically. Six years later he likes himself, is effective at school, and has healthy relationships at home and with friends.

ANGELICA

Angelica, age four, was very busy. Ever since she could walk, she ran. Her parents had to keep their eyes on her at all times. She ran off as soon as her mother, Jill’s, back was turned. She was her own “little wrecking crew” when she went shopping with her mom or dad. Her parents brought her to see me after she ran into the street and was almost hit by an oncoming car.

Angelica was also moody, irritable, oppositional, very talkative, and able to throw epic tantrums. Jill could not take Angelica anywhere without a commotion, which made the mother feel isolated and alone, which is not uncommon for mothers of ADD children. In restaurants she wiggled, yelled out, and screamed if she didn’t get her way. Other adults would stare at Angelica’s parents with disapproving looks that said, “Why don’t you beat that bratty child to behave better!” The parents often felt humiliated. Spanking, in fact, seemed to backfire. The more they spanked Angelica, the more she would act up—as if she wanted more punishment. Angelica had a very short attention span, never playing with anything for longer than a few minutes. She could tear her room apart in a moment.

Angelica tore up my office too. She messed up the papers on my desk, tossed books off my bookcase, and slapped her mother when she tried to get her to sit still. The parents were at their wits’ end. Angelica had the type of ADD we call the Ring of Fire. Likely, it had genetic roots. Jill’s father was an alcoholic and she had a brother who had been diagnosed with both ADD and bipolar disorder. Angelica’s father had a mother who had been hospitalized for suicidal thoughts. Angelica had already seen two child psychiatrists who had tried her on Ritalin and Adderall; both of these medications made her worse. She didn’t sleep or eat and was markedly more irritable. With an atypical response to medication, I ordered a brain SPECT study, which showed multiple areas of overactivity in her brain, which is why it is called the Ring of Fire (more on this pattern coming soon). As we will see, this pattern can have a number of causes, from food allergies, inflammation, or an early bipolar pattern. The goal of treatment was to eliminate anything that could be trouble for her and calm her brain. I put her on an elimination diet to see if she was sensitive to food, and placed her on a group of supplements to calm her brain, including omega-3 fatty acids, GABA, 5HTP, l-tyrosine, and brain-directed multiple vitamins. Within several weeks she became more settled, more cooperative, more playful, more attentive, and much more relaxed. Her mother was amazed at how little she was yelling at Angelica now. The parents also took a parenting class, which helped them gain the skills necessary to deal with a very challenging child.

Teenagers

KRYSTLE

Krystle’s mother came to one of my lectures. When I described ADD, she started to cry, knowing that the symptoms I had listed fit her daughter’s life. Shortly thereafter, she brought Krystle to our office. Krystle had a short attention span, was easily distracted, disorganized, and often did not finish her assignments. Even when she did them, she often forgot to turn them in. Krystle had low energy and struggled with motivation. She wanted to be a teacher, but believed she was not smart enough. She sat in my office, already demoralized at age fifteen.

Krystle had Inattentive ADD, a common but frequently undiagnosed condition in females. I started her on an omega-3 fatty acid supplement, a brain-directed multiple vitamin, and a low dose of a stimulant medication. In addition, I had her increase her exercise and protein intake, and worked with her on self-esteem and school strategies. Within two weeks of starting treatment, Krystle dramatically improved. I remember her coming into my office so tickled that she could finally get her work done. In the semester after she started treatment, her grade point average went from a 2.1 to a 3.2. She was thrilled that she could keep up with her friends at school and no longer thought of herself as “stupid.” The demoralized girl I had first met was developing into a hopeful and forward-looking woman.

GREGG

When Gregg first came to see me at the age of fourteen, he was a wreck. He had just been expelled from his third school for fighting and breaking the rules. He told off teachers for fun and picked fights with other kids on the school grounds. He also never did his homework and he talked about dropping out of school, saying he didn’t need an education to take care of himself. At home he was defiant, restless, messy, and disobedient. He teased his younger brother and sister without mercy. Anytime his parents would speak to him, he’d get defensive and challenging. His parents were at their wits’ end, and their next step was a residential treatment center.

When I first saw him he was a “turned-off” teenager with averted eyes and nothing much to say. He told me that he didn’t want to be sent away but that he wasn’t able to get along with his family. He found school very hard and thought he was stupid. When I did a test of verbal intelligence on him, however, his demeanor started to change. He liked the test and seemed challenged by it. His verbal IQ score was 142, in the superior range and far from stupid. Looking back in Gregg’s history, it was clear he had had symptoms of ADD his whole life. He was a fidgety kid with awful handwriting and a messy desk. He had trouble waiting his turn in school, and endured being called stupid because he had trouble learning.

Due to the severity of his problems, and the potential departure of Gregg from the family, I ordered a brain SPECT study to evaluate the functioning of his brain. The study showed that he had two problems. When Gregg tried to concentrate, the front part of his brain, which should increase in activity, actually decreased. This is the part of the brain that controls attention span, judgment, impulse control, and critical thinking. His brain study also showed decreased activity in his left temporal lobe, which, when abnormal, often causes problems with learning, and sometimes violent or aggressive behavior. I diagnosed Gregg with Temporal Lobe ADD.

As I explained these findings to Gregg, he became visibly relieved. “You mean,” he said, “the harder I try to concentrate, the worse it gets for me.” He responded very nicely to a combination of medication to balance the trouble in his frontal and temporal lobes (a stimulant and anticonvulsant), in addition to a brain-directed multiple vitamin, omega-3 fatty acid supplement, neurofeedback over his left temporal lobe, an improved diet, and exercise. He was able to remain at home, finish high school, and start college—a far cry from the stupid troublemaker he and everyone else thought he was.

Adults

BRETT

Brett, twenty-seven, had just been fired from his fourth job in a year. He blamed his bosses for expecting too much of him, but it was the same old story. Brett had trouble with details, he was often late to work, he seemed disorganized, and he would miss important deadlines. The end came when he impulsively told off a difficult customer who complained about his attitude.

All his life Brett had similar problems, and his mother was tired of bailing him out. He dropped out of school in the eleventh grade, despite having been found to have a high IQ. He was restless, fidgety, impulsive, and had a fleeting attention span. When he was in school, small amounts of homework would take him several hours to complete, even with much nagging and yelling from his mother. Brett had mastered the art of getting people angry at him, and it seemed to others that he intentionally stirred things up.

Brett had had lifelong symptoms of Classic ADD that had gone unnoticed, even though Brett had been tested on three separate occasions. With appropriate treatment at last, his life made a dramatic turnaround. He returned to school, finished a technical degree in fire-inspection technology, and got a job. He has kept that job for eight years now and feels that he is happier, more focused, and more positive than ever before.

LARRY

Larry, sixty-two, came into therapy because his wife threatened to start divorce proceedings against him if he didn’t get help. She complained that he never talked to her, he was unreliable, he never finished projects that he started, and he was very negative. He tended to be moody, tired, and disinterested in sex. As a child, he had mediocre to poor grades in school, and as an adult he went from job to job, complaining of boredom.

Larry was referred to me by his marital therapist, and rightly so: Larry had Limbic ADD, with problems that looked like a combination of ADD and mild, chronic depression.

Larry’s SPECT study showed decreased prefrontal cortex activity and increased activity in the deep limbic system of his brain. Seeing his scan convinced him of the need for treatment. He started on an intense aerobic exercise program, changed his diet, and took an omega-3 fatty acid supplement, a brain-directed multiple vitamin, and SAMe, a dietary supplement that has been shown to support mood and, in my experience, help with attention. Within a month his mood was better and he felt more focused. As Larry improved, the couple progressed quickly in marital therapy and have been happier than when they were first married.

SARAH

Sarah, forty-two, was anxious and frustrated when she first came to see me. She also complained of being irritable and short with her children and husband. Furthermore, she had trouble getting to sleep, which was new, and couldn’t get out of bed in the morning. In school, growing up, she was easily distracted, and homework took her forever to do. She often froze during tests and scored very poorly on timed tests. In addition, she would never speak up in class. In college, she purposefully took classes where there were no oral assignments. She told me if she had to give a presentation in class, she just didn’t show up. She would rather get an F than speak in front of the class.

Sarah’s grandmother, father, and sister had problems with anxiety. She also had two nephews who had been diagnosed with ADD. As I listened to her story, it was clear that Sarah had Anxious ADD, where her internal anxiety was constantly distracting her. Her lab tests were all fine, except she had a low progesterone level, which is common for many women in their early forties. When progesterone goes low, anxiety often increases, and can cause issues with sleep and anxiety. Sarah responded nicely to relaxation exercises, diet and exercise changes, and a combination of supplements to boost the neurotransmitter GABA and dopamine, omega-3 fatty acids, along with progesterone cream.