CHAPTER 2

ADD: Core Symptoms and Why It Is Increasing in the Population

Despite what it may seem from the constant media reports, ADD is not new. As early as the seventeenth century, the philosopher John Locke described a perplexing group of young students who, “try as they might, they cannot keep their minds from straying.” History is full of references to people fitting the symptom pattern of inattention, restlessness, hyperactivity, and impulsivity. Abraham Lincoln’s third son, Tad, fit the picture. He was described as hyperactive, impulsive (bursting into the Oval Office while chasing his brother), and inattentive. He had learning problems. His mother hired tutor after tutor to come into the White House to help Tad, but they all quit, saying that he was not teachable. One wonders if Mary Todd Lincoln didn’t have ADD herself. She too struggled with impulsivity. On a number of occasions she overspent the White House budget, causing political embarrassment and ridicule for the president. One time when President Lincoln was reviewing the troops, a young captain’s wife caught his eye. Mrs. Lincoln noticed her husband looking at the young woman and started screaming at her husband in front of the whole crowd.

ADD is not even new in the medical literature. George Still, a pediatrician at the turn of the last century, described children who were hyperactive, inattentive, and impulsive. Unfortunately, he labeled them “morally defective.” During the great flu epidemic of 1918, many children also contracted viral encephalitis and meningitis. Of those who survived the brain infections, many were described with symptoms now considered classic for ADD. By the 1930s, the label “minimal brain damage” was coined to describe these children. The label was changed in the 1960s to “minimal brain dysfunction” because no anatomical abnormality could be found in the children. Whatever its name, ADD has been part of the psychiatric terminology since the inception of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) in 1952. (The DSM is the diagnostic bible listing clinical criteria for various psychiatric disorders). Every version of the DSM has described the core symptoms of ADD, albeit by a different name every time.

ADD CORE SYMPTOMS

There is a group of core symptoms common to those who have ADD. These include short attention span for routine, everyday tasks, distractibility, organizational problems (for spaces and time), difficulty with follow-through, and poor internal supervision or judgment. These symptoms exist over a prolonged period of time and are present from an early age, although they may not be evident until a child is pushed to concentrate or to organize his or her life.

SHORT ATTENTION SPAN FOR REGULAR, ROUTINE TASKS

A short attention span is the hallmark symptom of this disorder. People with ADD have trouble sustaining attention and effort over prolonged periods of time, unless they are intensely interested. Their minds tend to wander and they frequently get off task, thinking about or doing other things than the task at hand. Yet, one of the things that often fools inexperienced clinicians assessing this disorder is that people with ADD do not have a short attention span for everything. Often, people with ADD can pay attention perfectly well to things that are new, novel, highly stimulating, interesting, or frightening. These things provide enough of their own intrinsic stimulation, which activates the brain functions that help people with ADD focus and concentrate. When asked about attention span, most people with ADD say that they can pay attention “just fine.” But they often spontaneously add the phrase “. . . if I’m interested.” That is the most important part of the answer: People with ADD need outside stimulation in order to focus. This is one of the reasons they often like scary movies, excitement-filled activities, such as driving fast, or a good argument.

In one study, researchers found a deficiency of adrenaline (the hormone frequently associated with stress or excitement) in the urine samples of ADD children.

I often think of ADD as “adrenaline deficit disorder,” because people with ADD can focus with excitement and interest, but not without it. My son who has ADD without hyperactivity (Type 2), for example, used to take four hours to do a half hour of homework, frequently getting off task. Yet, if you gave him a car stereo magazine, he would quickly read it from cover to cover and remember every little detail in it.

People with ADD have problems paying attention to regular, routine, everyday matters such as homework, schoolwork, chores, or paperwork—problems that have plagued them their whole lives. The mundane is terrible for them and not by choice. As we will see later on, they need excitement or interest to stimulate an underactive brain.

Attention patterns are crucial to a diagnosis of ADD. A person’s tendency to deny that they have attentional problems (because they can concentrate with intense interest) is often a roadblock to accepting the diagnosis or getting proper treatment. I make sure that I ask about attention span for regular, routine, everyday tasks. I also ask about attention span from others who know the person well. Other people may be better observers than the person being evaluated. Parents, siblings, spouses, and friends are often quick to complain about attention and focusing abilities, even when the person has completely denied any trouble concentrating.

In addition to clinical history (from family and friends as well as the person being evaluated), our office also uses the Conner’s Continuous Performance Task (C-CPT), to measure attention span and impulse control to aid in making the diagnosis of ADD. The Conner’s CPT is a computer-based fifteen-minute test of attention, response time, and impulse control. On the screen, letters flash at one-second, two-second, and four-second intervals. Every time you see a letter, you hit the space bar, except when you see the letter X. Whenever you see the letter X you just let it go and do not hit the space bar. People with ADD often have erratic response times (good when the letters come fast at one second intervals, but slower when the letters come at two- or four-second intervals) and more impulsive responses, hitting an excessive number of X’s. This test frustrates many people with ADD. We also use a sophisticated computerized neuropsychological test, called WebNeuro, that gives us scores on attention, impulsivity, memory, information processing speed, and executive function.

DISTRACTIBILITY

Distractibility differs from a short attention span. The issue here is not an inability to sustain attention, but rather a hypersensitivity to the environment. Most of us can block out unnecessary environmental stimuli: traffic sounds, the sound of the air conditioner or heater turning on, the smell of food from the cafeteria, birds flying by the classroom window, even the feel of our own clothing against our skin. People with ADD, however, are often hypersensitive to their senses, and they have trouble suppressing the sounds, sights, smells, and feel of the environment—the sensory noise that surrounds us. The distractibility is likely due to the underlying mechanism of ADD, underactivity in the prefrontal cortex of the brain.

The prefrontal cortex has many inhibitory tracks that signal other areas of the brain to settle down. It sends these inhibitory signals to the thalamus (a structure deep in the brain that gates incoming information) and the parietal lobes (our sensory cortex) so that we do not become overwhelmed or sense too much of the environment. However, when the prefrontal cortex is underactive, the thalamus and parietal lobes can bombard us with too much environmental information. The prefrontal cortex also sends inhibitory signals to the brain’s emotional centers. When this input is not strong enough, people get distracted by their internal thoughts and feelings.

Here are some examples: Many of my patients tell me that they frequently feel irritated by their own clothing. Most people never feel their own clothing unless their attention is directed to it. When directed to think about the shoes on your feet, you can easily feel them, but since you don’t need to pay attention to the feeling of your shoes, your brain blocks out the unnecessary sensation. People with ADD have trouble here. One of my daughters with Type 3 (Overfocused) ADD used to repetitively take off her socks if the seam was not perfectly aligned.

ADD patients also routinely cut the tags out of their clothing. I remember the weekend my ex-wife (who was later diagnosed with ADD) moved into my apartment after our wedding. Unbeknownst to me, she cut the tags out of all of my shirts. When I asked her why, she said she thought I would appreciate it. She hated how tags felt and always removed them from her clothing. I had never felt a tag in my life, and asked her if she wouldn’t mind asking me first next time before she took scissors to my clothes.

The hypersensitivity to touch can also cause sexual problems, because many people with ADD do not like to be touched, or they react negatively if touched the “wrong” way. The distractibility also makes it harder to have an orgasm. In lectures, I often ask, “What does an orgasm require, besides a reasonable lover?” The answer is focus. You have to pay attention to the feeling long enough in order to make it happen. Many people, especially women, with ADD struggle to have orgasms, and with the right treatment they feel so much better.

In a similar way, sight sensitivity is a frequent problem. While it may not seem like much of an issue, seeing too much can cause problems in many situations. When driving, for example, it is important to focus on the road. Many people with ADD, however, see everything around them, becoming bombarded with visual stimuli. Reading a book also requires you to block out extraneous visual stimuli. Unfortunately, many people with ADD are unable to do this and they are frequently distracted by the movements around them. Later in the book, I will write about the Irlen Syndrome, a visual processing problem, commonly associated with ADD. Many people with ADD also complain of being excessively bothered by sounds, especially the chewing sounds of others. I have several young patients who will not go to school because they are so bothered by the sounds that other students make. I once evaluated an inmate who told me that he got murderous thoughts when other inmates would drag chess pieces across the chess board while playing the game. The noise, he said, would make him crazy. Other patients have told me that they need white noise (such as that of fans) to block out the other sounds in the environment. My ex-wife used to sleep with a fan on in our room in order not to hear all of the other sounds in the house—whether it is seventy degrees out or twenty degrees out. I often hid under the covers to avoid the noise and the cold breeze from the fan.

Sensitivity to taste is another common problem. Many people with ADD will eat only foods with a certain taste or texture. Parents frequently complain that they have trouble finding foods their children will eat. One of my patients went through a two-year period where he would only eat burritos with peanut butter and bananas.

Organizational Problems (Space and Time)

Organizational struggles are also very common in ADD, specifically disorganization for space, time, projects, and long-term goals. A common ADD trait, space disorganization is often seen early in the lives of ADD children. When you look at their rooms, closets, dresser drawers, desks, or book bags, you frequently see a disaster. Things are left half done, half put away, or dropped wherever. I used to tell my son that his room followed the second law of physics, entropy, in which things degrade from order to disorder. His room showed hyper-entropy. I remember helping him clean his room on Sunday afternoons, but by Sunday evening it often looked a mess. Once, when he was in the third grade, I went to an open house at his school. All of the desks were in neat rows . . . except one. It was out of place with papers hanging out of it. My heart sank. I knew it was Antony’s desk, and when I opened the desk’s lid I saw his name.

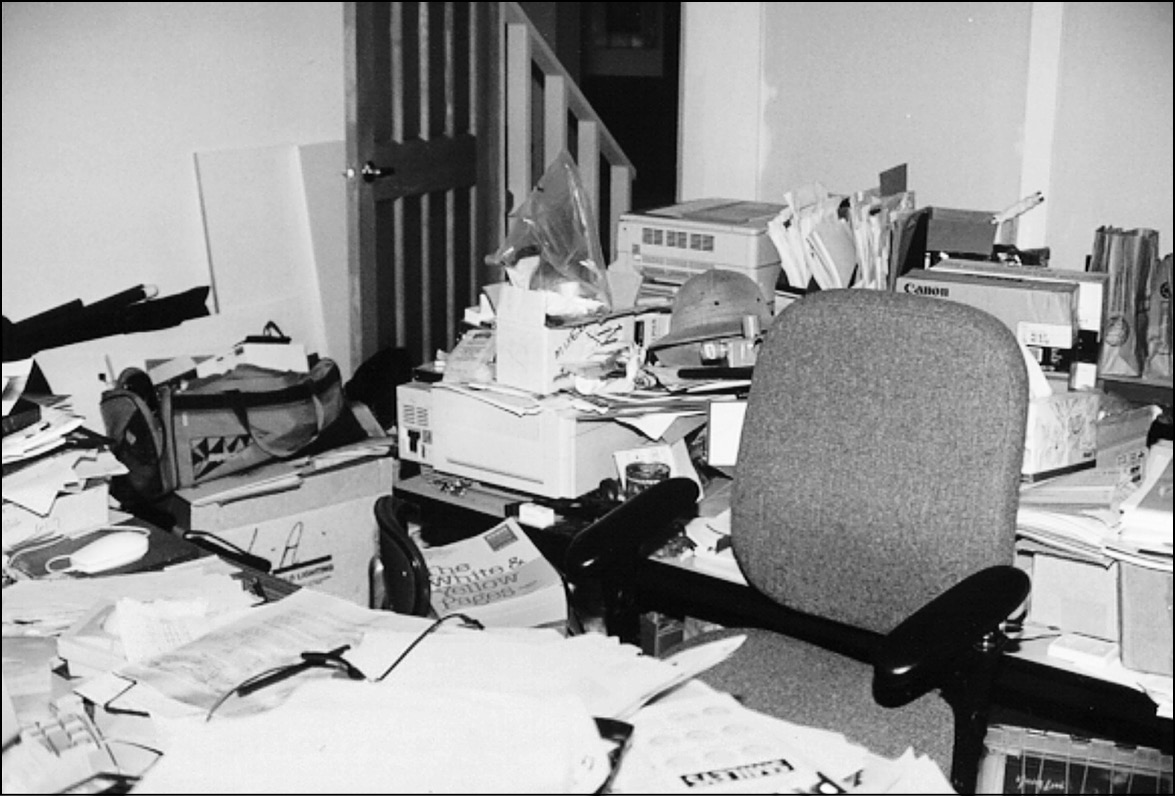

Other people often complain bitterly about the disorganization, such as bosses, teachers, children, and spouses. I have received letters from wives writing about their ADD husbands. “He’ll tell you he’s organized,” they write, “but I am enclosing a picture of his office [filing cabinet, closet, or garage]. What do you think?” The pictures show spaces that are incredibly overstuffed and disorganized.

People with Type 3 Overfocused ADD often appear very organized on the outside. They are often perfectly dressed, and parts of their living spaces may be very neat. For example, they may insist on perfect living rooms, but if you go into their drawers or their closets, you’ll find a disaster.

Similarly, time organization plagues people with ADD. They tend to be late and have trouble predicting how long things will take them to do. Often they will agree to do too many things at once, not realizing the time commitment involved. The chronic tardiness lands many ADD people in deep trouble. For example, they get fired from jobs for being late to work, not once, but on a chronic basis. Many of my patients’ spouses have told me that they have to lie in order to be on time for appointments or engagements. “If I tell her we have to leave at noon, invariably she won’t be ready until 12:30 or 1:00 P.M. It makes me so mad! So in order for me not to feel so stressed out I tell her we have to leave at 11:00. She hasn’t caught on yet.”

ADD people often take a haphazard or disorganized approach to projects or chores, dramatically increasing the time it takes to complete them. For example, one of my patients planned to clean out the garage over the weekend. On Friday night he put half of the garage contents into the driveway, but then he started organizing the boxes that were inside the garage. Three weeks later the neighbors started to complain about the mess in the driveway. One of the college students I treat complained about spending excessive time on projects. When I asked him to explain the process of doing a project, it was clear that it had no beginning, middle, or end: he was working on multiple ideas that did not have any structure to them.

In addition, many people with ADD take a disorganized approach to their own lives. They frequently lack long-term goals and tend to live from crisis to crisis or problem to problem.

DIFFICULTY WITH FOLLOW-THROUGH

People with ADD frequently suffer from poor follow-through, lacking the staying power to see projects through to the end. They will do something so long as there is intense interest. In addition, they put things off until the very last minute—until the looming deadline generates enough stress to entice them to get it done. For example, if there is a term paper due in a month, they will put it off, put it off, and put it off until they are pushed to the wall of the deadline, working feverishly to finish, even if they have told themselves that this time they will get to their project early.

Often people with ADD have so many different interests, they will only do a project as long as it holds their curiosity. I once saw a college professor for evaluation. His wife sat in on the initial session. I asked him how many projects he started last year. He said, “I think about three hundred.” His wife added in an irritated tone, “He only finished three, and none of them were for me.”

Many people with ADD will complete 50 to 80 percent of their task and then go off to another project. They frequently get distracted by other things and fail to follow through with the task at hand. Many people with ADD pay late fees on bills, even though they had the money to pay the bill on time.

Poor follow-through affects many areas of life. Here are some examples:

- schoolwork—fails to turn in assigned work

- chores at home—things often put off until the very last minute or not done at all

- work—reports or paperwork not turned in on time

- finances—late charges paid, even when the money is there because bills were not paid on time

- friendships—promises go unfulfilled

- health—fail to follow through on diets, taking supplements or medication, or getting their lab work done when asked.

POOR INTERNAL SUPERVISION

Many people with ADD have poor internal supervision. The prefrontal cortex (PFC) is the brain’s chief executive officer because it is so heavily involved with forethought, planning, impulse control, and decision making. North Carolina neuropsychiatrist Thomas Gualtieri, M.D., succinctly summarized the human functions of the PFC: “the capacity to formulate goals, to make plans for their execution, to carry them out in an effective way, and to change course and improvise in the face of obstacles or failure, and to do so successfully, in the absence of external direction or structure. The capacity of the individual to generate goals and to achieve them is considered to be an essential aspect of a mature and effective personality. It is not a social convention or an artifact of culture. It is hard wired in the construction of the prefrontal cortex and its connections.”

When there are problems in the prefrontal cortex, as is typical in ADD patients, forethought is a constant struggle. The PFC helps you think about what you say or do before you say or do it. The PFC helps you, in accordance with your experience, select among alternatives in social and work situations. For example, a person with good PFC function is more likely to have a tempered, reasonable disagreement with a spouse. A person with poor PFC function is more likely to do or say something that will make the situation worse. Likewise, if you’re a checkout clerk with good PFC function and a difficult, complaining person (who has poor PFC function) comes through your line, you are more likely to keep quiet or give a thoughtful response that helps the situation. If you have poor PFC function, you are more likely to do or say something that will inflame the situation. The PFC helps you problem-solve, see ahead of a situation, and, by learning through experience, pick between the most helpful alternatives.

The PFC is also the part of the brain that helps you learn from your mistakes. Good PFC function doesn’t mean you won’t make mistakes; everyone does. Rather, you won’t make the same mistake over and over. You are able to learn from the past and apply its lessons. A student with good PFC function can learn that if he or she starts a long-term project early, there is more time for research and less anxiety over getting it done. A student with decreased PFC function doesn’t learn from past frustrations and may tend to put everything off until the last minute. In general, poor PFC function leads people to make repetitive mistakes. Their actions are not based on experience, or forethought, but rather on the moment.

The moment is what matters. This phrase comes up over and over with my ADD patients. For many people with ADD, forethought is a struggle. It is natural for them to act out what is important to them at the immediate moment, not two moments from now or five moments from now, but now! A person with ADD may be ready for work a few minutes early, but rather than leave the house and be on time or a few minutes early, she may do another couple of things that make her late. Likewise, a person with ADD may be sexually attracted to someone he just met, and even though he is married and his personal goal is to stay married, he may have a sexual encounter that puts his marriage at risk. The moment was what mattered.

In the same vein, many people with ADD take what I call a crisis management approach to their lives. Rather than having clearly defined goals and acting in a manner consistent to reach them, they ricochet from crisis to crisis. In school, people with ADD have difficulty with long-term planning. Instead of keeping up as the semester goes along, they focus on the crisis in front of them at the moment—the next test or term paper. At work they are under continual stress. Deadlines loom and tasks go uncompleted. It seems as though there is a need for constant stress in order to get consistent work done. The constant stress, however, takes a physical toll on everyone involved (the person, his or her family, coworkers, employers, friends, etc.).

ADD IS INCREASING IN THE POPULATION

ADD is increasing in the population, a fact that frightens me, and it should frighten you as well. When you look at the fallout from untreated ADD, our society may be in for a lot more problems, especially considering that ADD remains underdiagnosed and undertreated. Thirty years ago, teachers would typically have one or two Classic ADD kids in their classrooms. Now I hear them say they have three, four, or five of these kids. What is happening? Are we just better at recognizing ADD? Are societal influences causing more ADD symptoms? One answer comes from David Comings, M.D., a geneticist from the City of Hope Hospital in Los Angeles. In his book The Gene Bomb he postulates that as our society becomes more technologically advanced, we require students to stay in school longer to get the best jobs. The students who drop out of the educational system first are those with ADD and learning disabilities. (Remember, 33 percent of untreated people with ADD never finish high school.) If you drop out of school first, what behavior are you likely to engage in first? You guessed it: sex. I see a much higher percentage of teenage pregnancies in ADD girls. They do not think through the consequences of their behavior. Also, according to Dr. Comings, ADD women have their first baby on average at the age of twenty. Non-ADD women have their first baby on average at the age of twenty-six. ADD women tend to have more children. Non-ADD women tend to have fewer children.

There is a historical example of how this childbearing dynamic can change a population. I am of Lebanese heritage. Lebanon was first made a country in 1943, but had long-standing roots in the Phoenician culture. At the time, in 1943, the country’s population was approximately half Christian and half Muslim. The Lebanese parliament was set up as half Christian and half Muslim to reflect the population. At the time, however, the Christians were better educated than their Muslim counterparts. They tended to stay in school longer. They also tended to have fewer children. Thirty-two years later—in 1975, when civil war broke out in Lebanon—the country was only one-third Christian and two-thirds Muslim. Part of the reason for the civil war was the change in population dynamics. In thirty-two years, a generation and a half, the population showed a dramatic shift.

Let’s bring this example closer to home. In 1972, renowned psychologist Thomas Auchenbauch performed a study to determine the incidence of learning and behavioral problems in children among the general population. At the time, using standardized instruments that he developed, he reported that 10 percent of the childhood population had learning or behavioral problems. A generation later, in 1992, he repeated the study using the same psychological instruments on basically the same population. He found a staggering difference: Eighteen percent of the childhood population now met the criteria for learning or behavioral problems. The incidence of problems had nearly doubled in a generation. Why? One reason is that ADD parents are having more ADD children.

SOCIETAL CONTRIBUTIONS TO ADD

There are other factors contributing to the rise of ADD and related problems in our society: an increase in processed foods and lower fat in the diet, excessive television and computer (phone, tablet) time, video games, and decreased exercise. Moreover, we are also better at diagnosing ADD. In addition to having improved psychological assessment tools, ADD has received repeated national exposure over the past twenty years. It has been on the cover of Time, Newsweek, and U.S. News & World Report. Almost all of the talk shows have done repeated programs on ADD, and there have been several national best-selling books. ADD has become part of movies, TV shows, courtroom dramas, and national legislation. We are at least better at thinking about it and talking about it. Over the last twenty years we have seen strong interest in the medical and mental-health community to learn more about ADD and get beyond the myths and the hype of ADD.

As far as excess television is concerned, the research is compelling: Kids who watch the most TV do the worst in school. TV is a “no brain” activity. Everything is provided to the brain (sounds, sights, plots, outcome, entertainment), so it doesn’t have to work to learn or make new connections. Like a muscle, the more you use your brain, the stronger it becomes and the more it can do. The opposite is also true: The less you work it, the weaker it becomes. Repeatedly engaging in “no brain” activities, such as TV, decreases a person’s ability to focus. In addition, the pacing of TV has changed over the past thirty years. Thirty years ago a thirty-second commercial had ten three-second scenes. The same commercial in 2000 has thirty one-second scenes. We are being programmed to need more stimulation in order to pay attention.

Video games are often another serious problem. I have seen that many ADD children literally become addicted to playing video games. They will play for hours at a time, to the detriment of their responsibilities, and go through tantrums and withdrawal symptoms when forced to stop. A study on brain-imaging and video games was published in the journal Nature. In the study, PET scans were taken while a group of people played action video games. The researchers were trying to see where video games worked in the brain. They discovered that the basal ganglia (where the “attention” neurotransmitter dopamine works in the brain) were much more active when the video games were being played than at rest. Both cocaine and Ritalin work in the basal ganglia. Side note: the reason cocaine is highly addictive and prescription stimulants like Ritalin tend not to be is related to how each drug is metabolized. Cocaine has a powerful, immediate effect that stimulates an enormous release of the neurotransmitter dopamine. The pleasure this brings rapidly fades, leaving the desire for more. Ritalin, and other stimulants like Adderall, on the other hand, work more slowly, inducing no high or pleasure in most people and the effects stay around for a longer time. Similarly, video games bring pleasure and focus by increasing dopamine release. The problem with them is that the more dopamine is released, the less neurotransmitter is available later on to do schoolwork, homework, chores, and so on.

Many parents have told me that the more a child or teen plays video games, the worse he does in school and the more irritable he tends to be when asked to stop playing. In a 2011 study, teens who reported five hours or more of video games/Internet daily use had a significantly higher risk for sadness, suicidal thoughts, and planning.

In another study from the Centers for Disease Control it was found that female video-game players reported greater depression and poorer overall health than nonplayers. Male video-game players reported a higher body mass index and more Internet use time overall than male nonplayers.

Another study from Norway found that as computer game playing increased there was a higher prevalence of sleeping problems, depression, suicide ideations, anxiety, obsessions/compulsions, and alcohol/ substance abuse. And, in a study published in the journal Pediatrics, a two-year study of elementary and high school children in Singapore found that the prevalence of pathological gaming was about 9 percent, similar to other countries. Lower social competence and greater impulsivity seemed to act as risk factors for becoming pathological gamers, whereas depression, anxiety, social phobias, and lower school performance seemed to act as the consequences of excessive gaming.

I saw the negative effects of video games in my own house. Nintendo came into our home when my son was ten years old. Initially, I thought that it was very cool. I never had exciting games like these when I was a child. I was outside playing basketball, baseball, or riding my bike with friends. But over the next few years I saw Antony spending more and more time with the video games and less time on his homework. Moreover, he would become argumentative when he was told to stop playing. I decided that Nintendo had to go. We were all better off without it.

One cannot overlook other aspects of the Internet as a potential source of serious problems for children and ourselves. The Internet is such a valuable source of information, but it is also filled with danger and time wasters. Because of the impulsivity and excitement-seeking nature of many people with ADD, they frequently visit sexually explicit sites, engage in racy conversations with others, and find creative ways to get into trouble. One of my teenage patients thought she fell in love on a dating site. She was seventeen when the story unfolded. She met a man from Louisiana in a chat room. They talked for hours, sent scanned photos, started talking over the telephone, and decided to marry after two months, even though they had never met in person. When I found out about it in therapy, I called a meeting with her parents. When she tried to break it off with this man, he threatened to kill her. We discovered that he had recently gotten out of prison for violent behavior. It’s essential that parents supervise time children spend on the Internet and that they put limits over the kinds of sites available. Recent studies have shown that the kids who spend the most time on the Internet have the poorest social skills. Balance and supervision are the biggest keys.

I have become more concerned recently about a child’s exposure to how computer and TV screens flash (or refresh themselves). If you look at some computer monitors or television screens through a video camera, you will see black lines quickly roll across the screen. TV and computer screens flash at different speeds, up to thirty flashes or cycles per second. Interestingly, this speed of flashing is similar to a concentration brain state. Your brain gravitates to that rhythm, and you tune in to whatever is drawing your attention—forced focus, so to speak. “Entrainment” is the technical term of this phenomenon: Your brain picks up the rhythm in the environment. So if a light (or TV) flashes at a slow rate, one’s brain picks up the slow rate and that person feels sleepy. If it flashes at a fast rate, you may feel energized or anxious. If your brain picks up a concentration flashing rate, you will focus on the TV or computer screen, even though you may not be at all interested in what’s on it. Have you ever had the experience of watching TV even though you didn’t want to—the feeling of being mesmerized or compelled to watch, even though you were bored with what was on? I have. One example of mass entrainment occurred in late 1997 in Japan. Tens of thousands of Japanese children were watching the top-rated Nintendo cartoon Pokémon. During one scene there was an explosion in which red, white, and yellow lights flashed at approximately 4.5 cycles (or flashes) per second for several seconds. All of a sudden kids started to have seizures. Seven hundred and thirty Japanese children went to emergency rooms that night, reporting seizures. Most of the children had never had a seizure before. The 4.5 cycles per second happened to be a seizure frequency. That was a dramatic example, but I wonder what all of this exposure to computer flashing is doing to our children. As far as I know, no one is studying it, and we should be.

Video games and television have led to another major contributor in the rise of ADD in our society: the lack of exercise. Exercise increases blood flow to all parts of the body, including the brain. As kids watch more TV and spend more time exercising only their thumbs with video games, they are becoming more sluggish and less attentive. Through the years I have seen a direct relationship between the level of exercise a person gets and the severity of their symptoms. I have seen a number of ADD professionals (such as physicians and attorneys) get through school by exercising two to four hours a day. I have also noted that when my ADD patients are playing sports, such as basketball, where there is intense aerobic exercise, they do better in school, without any change in their medication. Exercise is important on many levels, and we’ll talk more about it later on.