CHAPTER 7

Type 2: Inattentive ADD

The second most common type of ADD is Type 2: Inattentive ADD. Unfortunately, many of these people never get diagnosed. Instead they are labeled slow, lazy, spacey, or unmotivated. While Type 1 people bring negative attention to themselves with their hyperactivity, constant chatter, and conflict-driven behavior, Inattentive ADD folks tend to be quiet and distracted. Rather than cause problems in class, they are more likely to daydream or look out the window. They are not often impulsive and are less likely to blurt out inappropriate things. They are frequently thought of as couch potatoes who have trouble finding interest or motivation in their lives. Girls seem to have this type as much as or more than boys. As in Type 1 (Classic) ADD, dopamine is generally considered the neurotransmitter involved in Inattentive ADD—although, in this case, its imbalance is felt by another area of the brain.

Read the following four examples of Type 2 ADD. Seeing what these people went through and how they were helped gives a clear picture of the nature of Inattentive ADD.

Sara

Eight-year-old Sara was brought to our clinic by her mother and father. They were worried about her inability to pay attention. A few minutes of homework often took her three to four hours, with her parents upset at her for taking so long. She appeared spacey, internally preoccupied, and generally in her own world. Her room was usually very messy. She had poor social skills and often ignored children her own age whom her parents arranged to come over to the house to be her playmates. Even though she did not have a defiant attitude at home, she often simply did not do what was asked of her. She said that she had forgotten or didn’t hear the request. Her teacher said that she appeared to be a smart child but performed far below her potential. Her mind wandered in class and she had to be reminded to pay attention. She frequently made silly mistakes on tests and homework. Her handwriting was awful. Hearing and vision tests checked out normal, as did thyroid studies done by the pediatrician and tests for learning disabilities by the school psychologist. Sara had all the hallmarks of Type 2 ADD, but the parents were hesitant to start treatment, and wanted further evaluation. We did a SPECT study to evaluate her brain function. Clinically, she appeared to have Inattentive ADD. Sara’s SPECT study showed marked decreased activity when she tried to concentrate, especially in the prefrontal cortex. I prescribed a high-protein, low-carbohydrate diet (her diet before the evaluation had been almost entirely carbohydrates), regular exercise, and a regimen of 500 milligrams of L-tyrosine twice a day. Sara’s schoolwork and behavior improved within the first week of starting this regimen. Whenever Sara strayed from her treatment, she again became spaced-out and inattentive.

Chris

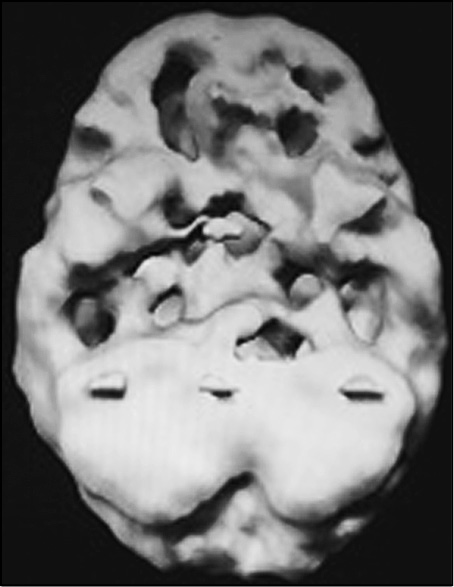

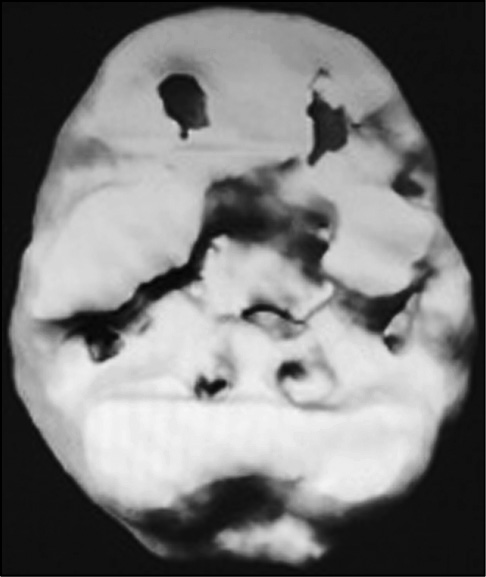

Ten-year-old Chris was diagnosed as mentally retarded at age six. He was a slow learner and now read at only the first-grade level. After testing Chris, the school psychologist said that he had only limited potential. His parents were very upset with the prognosis given by the school psychologist, because at home they saw flashes of real intelligence. They also saw problems: For example, his room tended to be very disorganized, even though the parents tried to help him. Chris had a low energy level and frequently had to be called on several times before he would answer. A local neurologist ordered a brain MRI, EEG, and blood tests, all of which were normal.

A friend of Chris’s mother was a patient at our clinic and suggested that she have Chris evaluated by us. Reviewing his tests, I saw not only that Chris had a low IQ, but also that the psychologist noted that Chris had been very inattentive during the test. In talking to Chris, I found that I had to work hard to make eye contact with him. He gave only limited answers to my questions and seemed easily distracted by the things in my office. I ordered a SPECT study to understand how his brain worked. I believe that all children diagnosed with mental retardation need a functional brain-imaging study. Overall, Chris had very poor blood flow in his brain, especially in the prefrontal cortex. I scanned him again on Adderall to see if it would have a positive effect. On Adderall he had significantly more activity in his brain. Almost immediately the parents noticed a difference in Chris. He was more talkative, more energetic, and more responsive. The next year he picked up three grade levels in reading. A year later, IQ tests were redone and found to be in the normal range. Today, Chris is happy and performing well in school. Prior to treatment, Chris’s brain was in darkness. Now, with treatment, the lights have been turned on: It was as if we had given a blind person sight.

Chris’s Concentration SPECT Study On and Off Adderall

(Underside Surface View)

No meds

With Adderall

Gary

Gary, age twenty-nine, came to see me because he had trouble living independently. His parents were still supporting him. Despite his high intelligence, he underachieved in school. Teachers said he didn’t care and needed to try harder. He appeared unmotivated, tired, and off in his own world. Even his girlfriend had trouble getting his attention. Even though he worked at several odd jobs and was good at carpentry, he did not make enough money to pay all of his bills. Employers fired him for being late to work or not coming back from lunch on time. Gary’s father told him to “get his stuff together” or he would not help Gary anymore.

Even though many people would call Gary lazy, I suspected a medical problem. Gary had symptoms consistent with Type 2 (Inattentive) ADD. Rather than being hyperactive, he appeared underactive. He was spacey, easily distracted, inattentive, and lethargic. His brain SPECT study showed marked decreased activity in the prefrontal cortex when he tried to concentrate. I placed him on a low dose of stimulant medication (Adderall), a higher-protein, lower-carbohydrate diet, and regular, intense exercise. Over the next two years he was able to become more effective in his day-to-day life.

Jenna

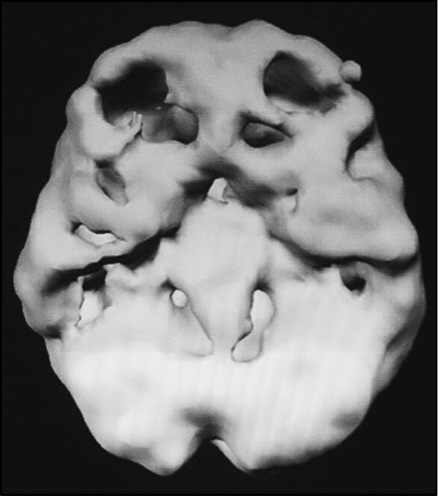

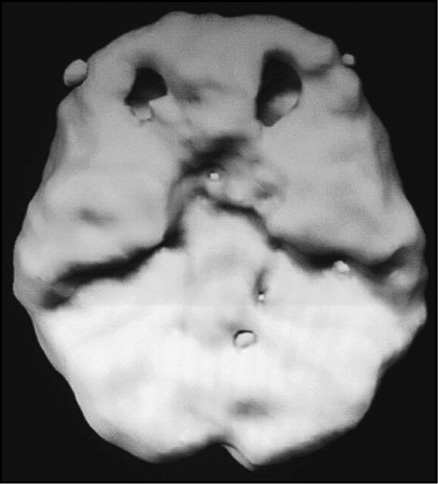

Jenna, a fifty-seven-year-old artist, was referred to Amen Clinics by her psychiatrist. She complained of trouble concentrating, distractibility, “fuzzy thinking,” disorganization, low energy, difficulty reading, and feelings of life being overwhelming. Facing the day was frightening for her. She would become frozen and panicked by daily tasks, such as opening the mail. She has a beautiful house, but there were piles everywhere. Many of her friends said that she was “too creative” to be organized and focused. Her doctor had tried her on a small dose of Ritalin, which had a significant positive effect on her symptoms. He wanted to send her for a second opinion and for brain-imaging studies to clarify the diagnosis and better target her treatment.

Clinically, Jenna was diagnosed with Type 2 (Inattentive) ADD. Two SPECT studies were performed as part of her workup. The first study, performed without any medication, showed marked decreased activity, especially in her prefrontal cortex. The second study was performed several days later after she took a dose of Adderall. With medication there was significant overall improvement throughout her whole brain, especially in the prefrontal cortex. On Adderall she feels much better. “I feel like I have access to much more of my own brain,” she told me, which indeed the SPECT study verified.

Initially, Jenna was very afraid of medication. She wanted to deal with her problems in a “natural” way. In fact, she had tried different diets, exercise, and meditation, with little effect. On medication, she feels more focused, and more organized, with more consistent energy and more brainpower. She still exercises, eats right, and meditates to help keep her brain healthy. She has asked me who the natural Jenna is, the one with the underactive brain or the one with the normal-looking brain. My bias is that she is really herself when her brain works right. Since our first visit in 1998, Jenna has referred most of her family to me because they struggle with very similar issues.

Type 2 ADD is usually very responsive to treatment. As the case studies illustrate, it is often possible to change the whole course of a person’s life if the disorder is properly diagnosed and treated.

Jenna’s Concentration SPECT Study On and Off Adderall

(Underside Surface View)

No meds

With Adderall