CHAPTER 9

Type 4: Temporal Lobe ADD

The temporal lobes, underneath your temples and behind your eyes are involved with memory, learning, mood stability, and visual processing of objects. Type 4: Temporal Lobe ADD is commonly associated with learning and behavioral problems. It is often seen in people with ADD who struggle with mood instability, irritability, dyslexia, and memory problems.

The SPECT studies seen in Temporal Lobe ADD show abnormalities in the temporal lobes (usually significant decreased activity) along with decreased activity in the prefrontal cortex during concentration tasks. These patients exhibit both prefrontal and temporal lobe symptoms. I saw this type of ADD very early in my brain imaging work, especially with our most difficult patients, and began to see a correlation with earlier head injuries. Associated with domestic violence and suicidal thoughts, this type of ADD can ruin a family.

Kris

The second brain SPECT study that I ever ordered was on Kris. By age twelve, Kris had a long history of emotional outbursts, increased activity level, short attention span, impulsiveness, school problems, frequent lying, and aggressive behavior. At age six, Kris was placed on methylphenidate (Ritalin) for hyperactivity but he became more aggressive and started to have visual hallucinations, so it was stopped. After he attacked a boy at school when he was eight years old, he was admitted to a psychiatric hospital in Alaska where his father was stationed in the military. He was given the diagnosis of depression and started on the antidepressant desipramine (Norpramin). It didn’t help. By the age of twelve, Kris had been seen for several years of psychotherapy by a psychiatrist/psychoanalyst in the Napa Valley. His parents were seen by the same psychiatrist as well to help them be more effective in handling Kris’s behavior.

The psychiatrist and mother did not get along very well. The psychiatrist frequently blamed the mother as the “biggest part of Kris’s problem.” It was true that Kris’s mother looked angry, but she felt that nothing she did ever worked with Kris. The psychiatrist told her that if only she would get into psychotherapy and deal with her own childhood issues then Kris’s problems would go away. Somehow his mother just didn’t believe that was true. Before Kris she had not been angry or upset.

Kris’s behavior escalated to the point where he became more aggressive and uncontrollable at home. When he attacked another child at school with a knife he was placed in a psychiatric hospital. I was on call the weekend Kris was admitted to the hospital. Seemingly by random chance he became my patient. To connect with my patients on the child psychiatry ward, I often played touch football with them. That day Kris was on my team. Every single play he cheated. When we were on defense, in between plays, he would move the ball three steps back and look at me with an expression that said, “Are you going to yell at me like my mother does?” I decided not to yell at Kris, but rather to scan his little brain to get some clues as to why he acted the way he did. I refused to play his ADD game of “get the adult angry.”

Kris’s brain SPECT study was very abnormal at rest, showing marked decreased activity in the left temporal lobe. It was 40 percent less active than his right temporal lobe. When Kris performed the concentration task there was marked decreased activity in the prefrontal cortex.

Given the temporal lobe problems, I placed Kris on the anticonvulsant medication carbamazepine (Tegretol) as a way to normalize his temporal lobe. Within a month he was a dramatically different child. He was more compliant, more social, and much more pleasant to be around. On the day he was discharged from the hospital I was on call again. I gathered my patients and we played football. Kris was on my team again. This time, on every single play he talked to me about what we were going to do in the game. His behavior was effective and goal directed rather than conflict driven.

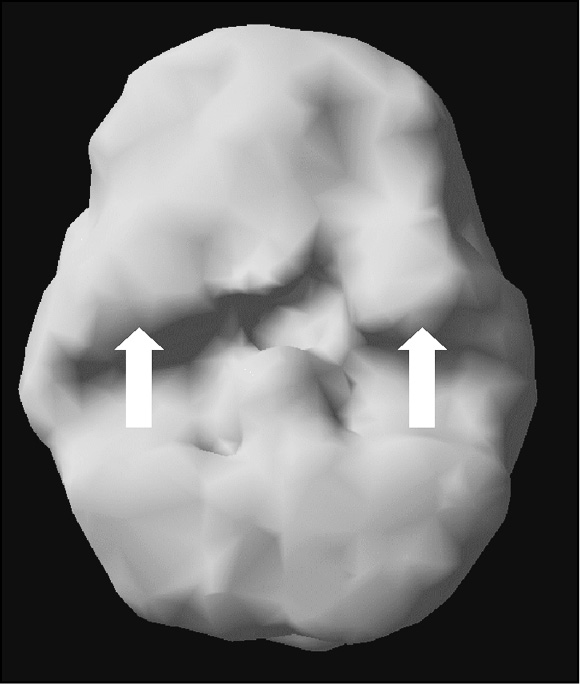

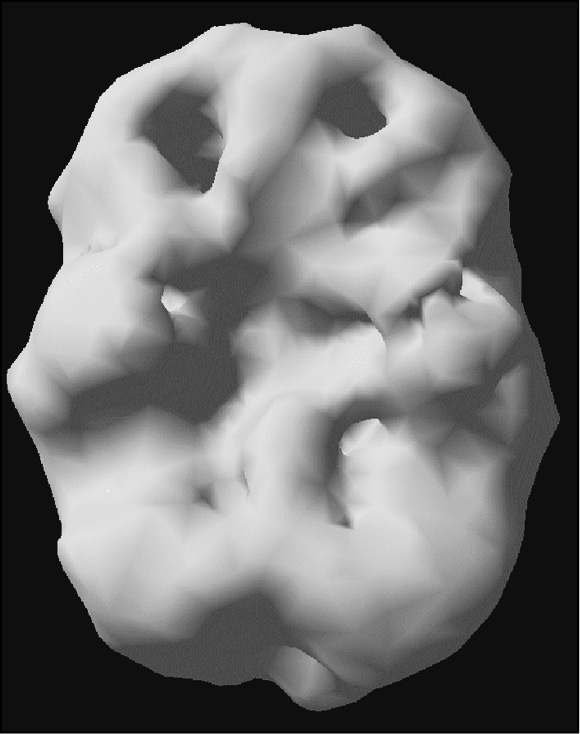

Kris’s SPECT Pictures

Underside surface view at rest. Mild decreased prefrontal and left temporal lobe

Underside surface view with concentration. Marked decreased prefrontal and left temporal lobe

When Kris went back to school his behavior was much better but he still struggled academically. Due to the fact that he had two problems (the left temporal lobe disorder and prefrontal cortex shutdown) I added the stimulant medication magnesium pemoline (Cylert). This helped his attention span and his schoolwork dramatically improved. His mother no longer looked like “the problem.” The positive response to treatment held for many years. Before his graduation from high school years after I met him, I gave a lecture to the teachers at his school. He saw me in the hallway and came up to me to introduce me to five of his friends.

What do you think would have happened to Kris if I hadn’t figured out that he had a temporal lobe problem? It is likely that he would have found himself in the California Youth Authority, juvenile hall, a residential treatment facility, or multiple psychiatric facilities. His mother would have continued to feel that she was the cause of his problems. I often feel sad when I think of all the children like Kris who never get the help they need. They get labeled as bad, willful, defiant children who need more punishment, rather than, what I see as the truth, children with medical problems who need treatment.

The temporal lobes play an integral part in memory, emotional stability, learning, temper control, and socialization. On the dominant side of the brain (usually the left side for most people) the temporal lobes are intimately involved with understanding and processing language, intermediate and long-term memory, complex memories, the retrieval of language or words, emotional stability, and visual and auditory processing.

Language is one of the keys to being human. It allows us to communicate with other human beings and it allows us to leave a legacy of our thoughts and actions for future generations. Receptive language, being able to receive and understand speech and written words, requires temporal lobe stability. The dominant temporal lobe helps to process sounds and written words into meaningful information. Being able to read in an efficient manner, remember what you read, and integrate the new information relies heavily on the dominant temporal lobe. Problems here contribute to language struggles, miscommunication, and reading disabilities.

Through our research we have also found that emotional stability is heavily influenced by this part of the brain. The ability to consistently feel stable and positive, despite the ups and downs of everyday life, is important for the development and maintenance of consistent character and personality. Optimum activity in the temporal lobes enhances mood stability, while increased or decreased activity in this part of the brain leads to fluctuating, inconsistent, or unpredictable moods and behaviors.

The nondominant temporal lobe (usually the right) is involved with reading facial expressions, processing verbal tones and intonations from others, hearing rhythms, appreciating music, and visual learning.

Recognizing familiar faces and facial expressions and being able to accurately perceive voice tones and intonations and give them appropriate meaning is critical to social skill. Being able to tell when someone is happy to see you, scared of you, bored, or in a hurry is essential for effectively interacting with others. A. Quaglino, an Italian opthamologist, reported on a patient in 1867 who, after a stroke, was unable to recognize familiar faces despite being able to read very small type. Since the 1940s, more than one hundred cases of prosopagnosia (the inability to recognize familiar faces) have been reported in the medical literature. Patients who have this disorder are often unaware of it (right hemisphere problems are often associated with neglect or denial of illnesses) or they may be ashamed at being unable to recognize close family members or friends. Most commonly, these problems were associated with right temporal lobe problems. Results of current research suggest that knowledge of emotional facial expressions is inborn, not learned (infants can recognize their mother’s emotional faces). Yet, when there are problems in this part of the brain social skills can be impaired.

The temporal lobes help us process the world of sight and sound, and give us the language of life. This part of the brain allows us to be stimulated, relaxed, or brought to ecstasy by the experience of great music. The temporal lobes have been called the “Interpretive Cortex,” as it interprets what we hear and integrates it with stored memories to give interpretation or meaning to the incoming information. Strong feelings of conviction, great insight, and knowing the truth have also been attributed to the temporal lobes.

Temporal lobe abnormalities occur much more frequently than previously recognized. The temporal lobes sit in a vulnerable area of the brain in the temporal fossa (or cavity), behind the eye sockets and underneath the temples. The front wall of the cavity includes a sharp bony ridge (the lesser wing of the sphenoid bone), which frequently damages the front part of the temporal lobes in even minor head injuries. Since the temporal lobes sit in a cavity surrounded by bone on five sides (front, back, right side, left side, and underside) they can be damaged from a blow to the head at almost any angle.

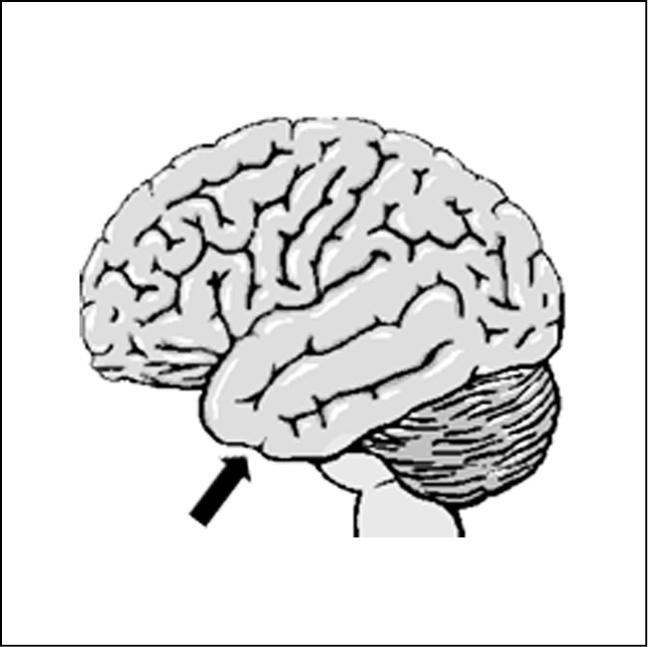

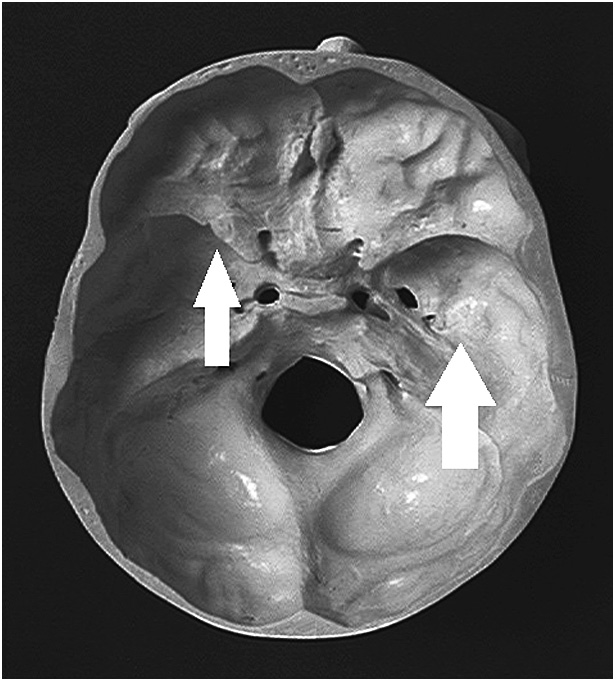

Model Showing the Base of the Skull

(Thick arrow points to temporal fossa where temporal lobes sit, thin arrow points to sharp edge of the lesser wing of the sphenoid bone)

As with other brain problems, temporal lobe problems can come from many different sources, the most common being genetic (you can get these problems from your parents), toxic or infectious exposure, and head injuries. In my clinic, we will ask you five times whether or not you ever had a head injury. (It amazes us how often people forget they have had head injuries!) Our intake paperwork will ask you if you’ve ever had a head injury. Our historians, who people see before seeing our physicians, ask this question. Our brain imaging information sheet asks this question. If we see that patients answer no, no, no to this question we’ll ask them again. If they say no for the fourth time we’ll ask, “Are you sure? Have you ever fallen out of a tree, off a fence, or dove into a shallow pool?” It is not uncommon for people to say, “Oh yeah, now I remember.” One man, after saying no four times to this question said, “Oh yeah, I fell out of a second story window. I forgot.” Other patients, after saying no four times, have told me about falling out of cars, going through car windshields, falling off porches five feet onto their heads, falling off balconies, down staircases, etc. Your brain is very soft and your skull is very hard. Your brain is more sophisticated than any computer we can design. You cannot just drop a computer and expect things will be okay. The temporal lobes, prefrontal cortex, and cingulate gyrus are the most vulnerable brain areas to damage by virtue of their placement within the skull. They are the most heavily involved parts of the brain in terms of thinking and behavior.

Jake

Jake, age sixty-five, came to see me from Mississippi. His wife heard me on national television and she was sure he had a temporal lobe problem. He was moody, had memory problems, and was often aggressive. Jake often heard bees “buzzing,” even though no bees were around. The temper problems seemed to come out of nowhere. “The littlest things seem to set me off. Then I feel terribly guilty,” he said. When Jake was fifteen years old, he was in a diving accident where he hit his head on the board and was unconscious for several minutes. After the accident, he had more problems in school and more problems with his temper. His brain SPECT study showed decreased activity in both the front and back of the left temporal lobe (a pattern frequently seen in head injuries) and decreased activity in his prefrontal cortex. Seeing this pattern, it was clear to me that many of Jake’s problems came from the poor activity in his left temporal lobe and PFC, likely from the teen accident. I placed him on Depakote (an antiseizure medication known to stabilize activity in the temporal lobes) and Adderall, along with the other Type 4 suggestions given later. When I spoke to Jake and his wife three weeks later they were very pleased. The temper outbursts stopped completely and he felt more focused and energetic. Six years later his temper remains under control.

TEMPORAL LOBE PROBLEMS

Common problems seen with left temporal lobe abnormalities include aggression—internally or externally driven, dark or violent thoughts, sensitivity to slights, mild paranoia, word-finding problems, auditory processing problems, reading difficulties, and emotional instability.

The aggressiveness often seen with left temporal lobe abnormalities can either be externally expressed toward others or internally expressed in aggressive thoughts toward oneself. Aggressive behavior is complex, but in a large study performed in my clinic on people who had assaulted another person or damaged property, more than 70 percent had left temporal lobe abnormalities. It seems that temporal lobe damage or dysfunction makes a person more prone to irritable, angry, or violent thoughts. One patient of mine with temporal lobe dysfunction (probably inherited, as his father was a rageaholic) complains of frequent, intense violent thoughts. He feels shame over having these thoughts and didn’t understand where they came from. “I can be walking down the street,” he told me, “and someone accidentally brushes against me, and I get the thought of wanting to shoot him or club him to death. These thoughts frighten me.” Thankfully, even though his SPECT confirmed left temporal lobe dysfunction, he had good prefrontal cortex function so he is able to supervise his behavior and maintain impulse control over these terrible thoughts. In a similar case, Misty, a forty-five-year-old woman, came to see me for anger outbursts. One day, someone accidentally bumped into her in the grocery store and she started screaming at the woman, which was the reason she came to see me. “I just don’t understand where my anger comes from,” she said. “I’ve had sixteen years of therapy and it is still there. Out of the blue, I’ll go off. I get the most horrid thoughts. You’d hate me if you knew.” In her history she noted that she had fallen off the top of a bunk bed when she was four years old. She was unconscious for only a minute or two. The front and back part of her left temporal lobe was clearly damaged. A small dose of an anticonvulsant medication was very helpful to calm the monster within.

I often see internal aggressiveness with left temporal lobe abnormalities, expressed in suicidal behavior. In a study from our clinic, we saw left temporal lobe abnormalities in 62 percent of our patients who had serious suicidal thoughts or actions. After I gave a lecture about the brain in Oakland a woman came up to me in tears. “Oh Dr. Amen,” she said, “I know my whole family has temporal lobe problems. My paternal great grandfather killed himself. My father’s mother and father killed themselves. My father and two of my three uncles killed themselves and last year my son tried to kill himself. Is there help for us?” I had the opportunity to evaluate and scan three members in her family. Two had left temporal lobe abnormalities and anticonvulsant medications were helpful in their treatment.

In terms of suicidal behavior, one very sad case highlights the involvement of the left temporal lobes. For years I wrote a column in my local newspaper about the brain and behavior. One column was about temporal lobe dysfunction and suicidal behavior. A week or so later a mother came to see me. She told me that her twenty-year-old son had killed himself several months ago and she was grief stricken over the unbelievable turn of events in his life. “He was the most ideal child a mother could have,” she said. “He did great in school. He was polite, cooperative, and a joy to have around. Then it all changed. Two years ago he had a bicycle accident. He accidentally hit a branch in the street and was flipped over the handlebars, landing on the left side of his face. He was unconscious when an onlooker got to him, but shortly thereafter came to. Nothing was the same since then. He was moody, angry, easily set off. He started to complain of ‘bad thoughts’ in his head. I took him to see a therapist, but it didn’t seem to help. One evening, I heard a loud noise out front. He had shot and killed himself on our front lawn.” Her tears made me get teary. I knew that her son might well have been helped if someone had recognized that his “minor head injury” likely caused temporal lobe damage and that anticonvulsant medication may well have prevented his suicide. Of interest, in the past twenty years psychiatrists have been using anticonvulsants to treat many psychiatric problems. My suspicion is we are treating underlying brain problems we label as “psychiatric.”

In addition to aggression, we have seen people with left temporal lobe abnormalities be more sensitive to slights and even appear mildly paranoid. Unlike people with schizophrenia who can become frankly paranoid, temporal lobe dysfunction often causes a person to think others are talking about them or laughing at them when there is no evidence for it. This sensitivity can cause serious relational and work problems.

Reading and language processing problems are also common when there is dysfunction in the left temporal lobe. It is currently estimated that nearly 20 percent of the U.S. population has difficulty reading. Our studies of people with dyslexia (underachievement in reading) often show underactivity in the back half of the left temporal lobe. Dyslexia can be inherited or it can be brought about after a head injury, damaging this part of the brain. Here are two illustrative cases.

Thirteen-year-old Denise came to see me because she was having problems with her temper. She had pulled a knife on her mother, which precipitated the referral. She also had school problems, especially in the area of reading for which she was in special classes. Due to the seriousness of her aggression and learning problems I decided to order a SPECT study at rest and then again when she tried to concentrate. At rest her brain showed mild decreased activity in the back half of her left temporal lobe. When she tried to concentrate the activity in her left temporal lobe completely shut down. As I showed Denise and her mother the scans, I told Denise that it was clear that the more she tried to read the harder reading would become. As I said this she burst into tears. She cried, “When I read I am so mean to myself. I tell myself, ‘Try harder. If you try harder then you won’t be so stupid.’ But trying harder doesn’t seem to help.” I told her it was essential for her to talk nicely to herself and that she will do better reading in a setting that is interesting, fun, and relaxed. I sent Denise to see an educational therapist. She taught her a specialized reading program that showed her how to visualize words and use a different part of the brain to process reading.

Carrie, a forty-year-old psychologist, came to see me two years after she sustained a head injury in a car accident. Before the accident, she had a remarkable memory and she was a fast, efficient reader. She said reading was one of her academic strengths. After the accident, she had memory problems, struggled more with irritability, and reading became difficult for her. She said that she had to read passages over and over to retain any information and that she had trouble remembering what she read past just a few moments. Again, her SPECT study showed damage to the front and back of her left temporal lobe (the pattern typically seen in trauma). I had her see my biofeedback therapist to enhance activity in her left temporal lobe. Over the course of four months she was able to regain her reading skills and improve her memory and control over her temper.

In our experience, left temporal lobe abnormalities are more frequently associated with externally directed discomfort (such as anger, irritability, aggressiveness), while right temporal lobe abnormalities are more likely associated with internal discomfort (anxiety and fearfulness). The left-right dichotomy has been particularly striking in our clinic population. One possible explanation is the left hemisphere of the brain is involved with understanding and expressing language and perhaps when the left hemisphere is involved one could express their discomfort. When the nondominant hemisphere is involved the discomfort is more likely expressed nonverbally.

Nondominant (usually right) temporal lobe problems more often involve social skill problems, especially in the area of reading and recognizing facial expressions and recognizing voice intonations. Mike, age thirty, illustrates the difficulties we have seen when there is dysfunction in this part of the brain. Mike came to see me because he wanted a date. He had never had a date in his life and was very frustrated by his inability to meet and successfully ask a woman out on a date. During the evaluation Mike said he was at a loss as to what his problem was. His mother, who accompanied him to the session, had her own ideas. “Mike,” she said, “misreads situations. He has always done that. Sometimes he comes on too strong, sometimes he is withdrawn when another person is interested. He doesn’t read the sound of my voice right either. I can be really mad at him and he doesn’t take me seriously. Or he can think I’m mad, when I’m nowhere near mad. When he was a little boy, Mike tried to play with other children but he could never hold on to friends. It was so painful to see him get discouraged.” Mike’s SPECT showed marked decreased activity in his right temporal lobe. His left temporal lobe was fine. The intervention that was most effective for Mike was intensive social skills training. He worked with a psychologist who coached him on facial expressions, voice tones, and proper social etiquette. He had his first date six months after coming to the clinic.

Abnormal activity in either or both temporal lobes can cause a wide variety of symptoms including: abnormal perceptions (sensory illusions), memory problems, feelings of déjà vu (that you have been somewhere before even though you haven’t), jamais vu (not recognizing familiar places), periods of panic or fear for no particular reason, periods of spaciness or confusion, and preoccupation with religious or moral issues. Illusions are very common temporal lobe symptoms. Common illusions include:

- seeing shadows or bugs out of the corner of the eyes

- seeing objects change size or shape (one patient would see lampposts turn into animals and run away, another patient would see figures move in a painting)

- hearing bees buzzing or static from a radio

- smelling odors or getting odd tastes in the mouth

- feeling bugs crawling on skin or other skin sensations

- Unexplained headaches and stomachaches also seem to be common in temporal lobe dysfunction.

Several of the anticonvulsants are used for migraine prevention, including Depakote and Neurontin. Often when headaches or stomachaches are due to temporal lobe problems anticonvulsants seem to be helpful. Periods of déjà vu (the feeling you’ve been somewhere before even though you never have) and jamais vu (feeling unfamiliar in familiar surroundings) also are seen in temporal lobe states. Also, unexplained periods of anxiety or fearfulness is one of the most common presenting symptoms with temporal lobe epilepsy. Many patients experience sudden feelings of anxiety, nervousness, or panic. Frequently, many patients make secondary associations to the panic and develop fears or phobias. For example, if the first time you experience the feeling of panic or dread is when you are in a grocery store or at a park, you may then develop anxiety every time you go into a grocery store or go to the park.

Moral or religious preoccupation is a common symptom with temporal lobe dysfunction. I have a little boy in my practice who, at age six, made himself physically sick by worrying about all of the people who were going to hell. Another patient spent seven days a week in church, praying for the souls of his family. He came to see me because of his temper problems, frequently directed at his family, which were often seen in response to some perceived moral misgiving or outrage. Another patient came to see me because he spent hours focused on the “mysteries of life,” could not get any work done, and was about to lose his job as a writer for a Bay Area magazine. All of these patients had temporal lobe abnormalities.

Hypergraphia, a tendency toward compulsive and extensive writing, has also been reported in temporal lobe disorders. One wonders whether Ted Kaczynski, the reported Unabomber, didn’t have temporal lobe problems given the lengthy, rambling manifesto he wrote, his proclivity toward violent behavior, and his social withdrawal. Some of my temporal lobe patients spend hours and hours writing. One patient, who moved to another state, used to write me twenty- and thirty-page letters, detailing all of the aspects of her life. As I learned about temporal lobe hypergraphia and had her treated with anticonvulsant medication her letters became more coherent and were shortened to two to three pages, saying the same information. Of note, many people with temporal lobe problems have the opposite of hypergraphia; they are unable to get words out of their heads and have a paucity of writing. One of the therapists in my office, who’s a wonderful public speaker, could not get the thoughts out of his head to write his book. On his scan there was decreased activity in both of his temporal lobes. On a very small dose of Depakote his ideas were unlocked and he could now write for hours at a time.

Memory problems have long been one of the hallmarks of temporal lobe dysfunction. Amnesia after a head injury is frequently due to damage to the inside aspect of the temporal lobes. Brain infections also cause severe memory problems. Harriet came to see me from New England. She was a very gracious eighty-three-year-old woman who had lost her memory fifteen years earlier during a bout of encephalitis. Even though she remembered events before the infection she could only remember small bits and pieces after the accident. An hour after she ate she would feel full but forgot what she ate. Her daughter heard me lecture in Burlington, Vermont, and told her to come see me. Harriet said, “I left my brain to the local medical school, hoping my problems would help someone else, but I don’t think they’ll do anything with my brain except give it to medical students to cut up. Plus I want to know what the problem is. And write it down. I won’t remember what you tell me!” Harriet’s brain showed marked damage in both temporal lobes, especially on the left side, like the virus went to that part of her brain and chewed it away.

Jenny

Jenny, sixteen, tried to kill herself the night before I first met her. Her boyfriend had just broken up with her. He told her that he was tired of the fights she started with him. She told him that she would kill herself if he left. When he started to leave, she took a knife and cut her wrist. He called the police who took her to the hospital. At that time Jenny was also having problems in school. Many of Jenny’s teachers said she was not living up to her potential and that she needed to try harder. There were also many fights between Jenny and her parents. Whenever they asked her to do something around the house she would fly into a rage. Over the last year she had broken a window and put several holes in walls and doors. Taking the history, I learned that at the age of eight, Jenny had fallen off her bike face-first onto the cement. She had lost consciousness for about ten minutes. Since the accident, she had complained of headaches and vague abdominal pain. Her pediatrician told her mother that it was just stress. Jenny was also overly sensitive to perceived slights, she frequently saw shadows that were not there, she had periods of anxiety with little provocation, and she had trouble with reading and memory.

Jenny had Temporal Lobe ADD, one of the most difficult behavioral types of this disorder. She had trouble with inattention and impulse control. She was also conflict-seeking and underachieved in school. In addition, she had specific temporal lobe symptoms, such as headaches and abdominal pain, illusions, periods of anxiety for little reason, hypersensitivity to others, and memory and reading problems. One of the hallmarks of Temporal Lobe ADD is aggression. She had both external aggression (toward others and objects) and internal aggression (toward herself: the suicide attempt). Her brain SPECT study showed decreased activity in the prefrontal cortex (giving her trouble concentrating) and decreased activity in her left temporal lobe (probably from the head injury that predated the onset of many symptoms). I placed her on the anticonvulsant Neurontin, which stabilized her mood instability and temper, and Adderall, which helped her attention span and impulsiveness. In addition, she changed her diet and exercised every day. Six years later she remains much better. She has just finished college and has been in a stable relationship for two years.

Jenny

Low prefrontal and left temporal lobe activity

Omar

Omar, thirty-two, was sent to our clinic by his defense attorney after he had been arrested for felony spouse abuse. Omar was Jordanian and he was married to a woman from Lebanon. They had been in the United States for four years. On six occasions in the last four years Omar had lost his temper and assaulted his wife. On the last occasion he broke her ribs and left arm. His explosions seemed to come out of the blue. His wife said that some days he woke up “different.” On certain days he had headaches, was overly sensitive, and nothing his wife did was right. All his life he had the core symptoms of ADD. He did poorly in school, despite being of above average intelligence. His teachers said that he was impulsive and had a short attention span. Homework used to take him half the night to do with his mother standing over him to get it done. He was disorganized and frequently late to obligations. Despite his problems, he had risen to a top salesperson in his company and he was responsible for other salespeople at work. Due to his explosive rage he had attended psychotherapy and an anger management class. They did not seem to make much difference. He also had seen a psychiatrist who had diagnosed him with ADD and given him Ritalin. The Ritalin made him feel speedy and irritable.

Our feeling is that anyone who assaults another person should have a brain scan. Omar’s SPECT study showed decreased activity in both of his temporal lobes and decreased activity in the prefrontal cortex. He was placed on Neurontin and Adderall and given the dietary and exercise advice for this type. Over the next three months I adjusted his medication dosages and his temper cooled while his ability to focus and organize himself improved. The scans were used in his court case. As part of the plea agreement, Omar had to do community service and see a psychiatrist every month for five years. If he dropped out of treatment he would be taken to prison.

Frequently, stimulants, such as Ritalin or Adderall, make this ADD type worse if they are given without anticonvulsant medication to stabilize temporal lobe function. They cause people to be irritable and sometimes more aggressive. Stabilizing the temporal lobes with anticonvulsant medications, such as Lamictal, Depakote, or Neurontin can literally rescue a life from despair, hatred, and self-loathing. After the temporal lobes are treated, a stimulant medication may be very helpful for concentration.

Jacob

Jacob lived with his grandparents. His mother was a drug addict and unable to care for him. Jacob was exposed to drugs in utero. When I saw him at the age of six he was hyperactive, very impulsive, easily distracted, struggled with learning, and had severe temper problems. His pediatrician had diagnosed him with ADD and put him on a stimulant medication, but four days later he had visual hallucinations. He saw what he described as ghosts (green blobs) floating around him. He also became much more irritable. The pediatrician referred Jacob to me. I ordered a SPECT study to evaluate his temporal lobes and also to see if there was drug damage still evident from his in utero exposure. It was no surprise when I saw overall decreased activity in his brain, especially in the area of the left temporal lobe. Jacob’s temper improved on an anticonvulsant. A month later I started Adderall to help his attention span. A year later he was much better.

John

John, a seventy-nine-year-old contractor, had a longstanding history of alcohol abuse and violent behavior. He had frequently physically abused his wife over forty years of marriage and had been abusive to the children when they were living at home. Almost all of the abuse occurred when he was intoxicated. As a boy he had been described as hyperactive, slow in school, and impulsive. At age seventy-nine, John underwent open-heart surgery. After the surgery he had a psychotic episode, lasting ten days. His doctor ordered a SPECT study as part of his evaluation. The study showed marked decreased activity in the left outside frontal-temporal region, a finding most likely due to a past head injury, and decreased activity in his prefrontal cortex. When the doctor asked John if he had ever had any significant head injuries, John told him about a time when he was twenty years old. While driving an old milk truck, that was missing its side-rear mirror, he put his head out of the window to look behind him. His head struck a pole, knocking him unconscious for several hours. After the head injury he had more problems with his temper and memory. There was a family history of alcohol abuse in four of his five brothers, but none of his brothers had problems with aggressive behavior. Given the location of the brain abnormalities (left frontal-temporal dysfunction) he was more likely to exhibit violent behavior. The alcohol abuse, which did not elicit violent behavior in his brothers, did in him. He was placed on carbamazepine and Adderall. His behavior was much more even and he was able to focus better than he had even when he was a child.

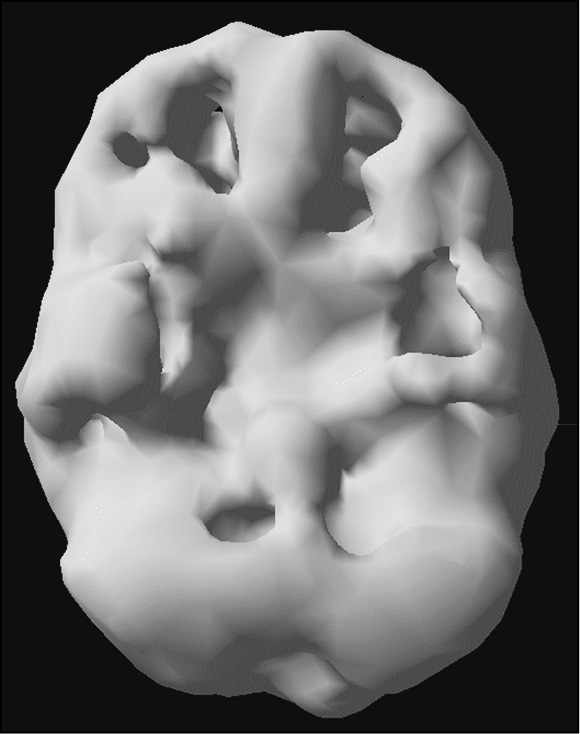

John’s Concentration SPECT Study (Left Side Surface View)

Left side surface view (Note marked area of decreased activity in the left frontal and temporal region)

Neil

Neil, a seventeen-year-old male, was diagnosed with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and left temporal lobe dysfunction (diagnosed by EEG) at the age of fourteen. Before then (from grades one to eight) he had been expelled from eleven schools for fighting, frequently cut school, and had already started drinking alcohol and using marijuana. He had a dramatically positive response to 15 milligrams of methylphenidate (Ritalin) three times a day. He improved three grade levels of reading within the next year, attended school regularly, and had no aggressive outbursts. His grandmother (with whom he lived) and his teachers were very pleased with his progress. However, Neil had a negative emotional response to taking medication. He later said that taking his medication, even though it obviously helped him, made him feel stupid and different. Two years after starting his medication, he decided to stop it on his own without telling anyone. His anger began to escalate again, as did his drinking and marijuana usage. One night, while he was intoxicated, his uncle came over to his home and asked Neil to help him “rob some women.” Neil went with his uncle who forced a woman into her car and made her go to her ATM and withdraw money. The uncle and Neil then raped the woman twice. He was apprehended two weeks later and charged with kidnapping, robbery, and rape.

I was asked by Neil’s defense attorney to evaluate Neil. I agreed with the clinical history of ADD and suspected left temporal lobe dysfunction because of the chronic aggressive behavior and abnormal EEG. I ordered a series of brain SPECT studies: one at rest, one while he was doing a concentration task, and one on methylphenidate. The rest study showed mild decreased activity in the prefrontal cortex and the left temporal lobe. While performing a concentration task, there was marked suppression of the prefrontal cortex and both temporal lobes. The third scan was done one hour after taking 15 milligrams of methylphenidate. This scan showed marked activation in the prefrontal cortex and both temporal lobes.

After understanding the history and reviewing the scan data, it was apparent that Neil already had a vulnerable brain that was consistent with long-term behavioral and academic difficulties. His substance use may have further suppressed an already underactive prefrontal cortex and temporal lobe, diminishing executive abilities and unleashing aggressive tendencies. It is possible that with an explanation of the underlying metabolic problems and brief psychotherapy on the emotional issues surrounding the need to take medication, this serious problem might have been averted. In prison, he was placed on an anticonvulsant and had no aggressive outbursts for the past two years.

DIFFERENTIATING TYPE 4 TEMPORAL LOBE ADD FROM TEMPORAL LOBE EPILEPSY

I am often asked how to differentiate Type 4 Temporal Lobe ADD from temporal lobe epilepsy. This can be challenging. Both disorders are due to abnormal activity in the temporal lobes. Both disorders are helped with anticonvulsant medication. Temporal Lobe ADD may be a combination of a variant of temporal lobe epilepsy that is comorbid with ADD. In order for the diagnosis to be Temporal Lobe ADD there needs to be long-standing core ADD symptoms in addition to the temporal lobe symptoms. Many people with TLE do not have ADD symptoms and so would not fall into the Temporal Lobe ADD category.

THE TREATMENT DEPENDS ON A COMBINATION OF THE SYMPTOMS AND SCAN FINDINGS

Not everyone who has temporal lobe problems on SPECT needs to be placed on anticonvulsant medication. When there is mood instability, irritability, or temper problems, we tend to use anticonvulsants. When there is learning or memory problems we tend to use supplements, such as gingko, vinpocetine, and phosphatidylserine, or medications, such as Aricept or Namenda—medications originally developed for Alzheimer’s disease, to enhance learning and memory. More on this in the medication and supplement chapters.