CHAPTER 22

Neurofeedback Strategies for ADD Types

In late 2012, the American Academy of Pediatrics recognized neurofeedback as a Level 1: “Best Support” Intervention for ADD on par with medication. Over the past thirty years, Joel Lubar, Ph.D., of the University of Tennessee, and many other clinicians have reported the effectiveness of brain wave biofeedback, also known as neurofeedback, in the treatment of ADD in children and teenagers.

In 2013, in a high-quality study from Spain published in the prestigious journal Biological Psychiatry researchers compared forty sessions of neurofeedback to Ritalin. Behavioral rating scales were completed by fathers, mothers, and teachers at pre- and post-treatment, and at two- and six-month follow-up. In both groups, similar significant reductions were reported in ADHD symptoms by parents and teachers. However, significant academic performance improvements were only detected in the neurofeedback group.

Biofeedback, in general, is a treatment technique that utilizes instruments to measure physiological responses in a person’s body (such as hand temperature, sweat gland activity, breathing rates, heart rates, blood pressure, and brain wave patterns). The instruments then feed the information on these body systems back to the patient who can then learn how to change them. In neurofeedback, electrodes are placed on the scalp, measuring the number and type of brain wave patterns.

There are five types of brain wave patterns:

- delta waves (1 to 4 cycles per second), very slow brain waves, seen mostly during sleep

- theta waves (5 to 7 cycles per second), slow brain waves, seen during daydreaming and twilight states

- alpha waves (8 to 12 cycles per second), brain waves seen during relaxed states

- SMR (sensorimotor rhythm) waves (12 to 15 cycles per second), brain waves seen during states of focused relaxation

- beta waves (13 to 24 cycles per second), fast brain waves seen during concentration or mental work states

In evaluating over twelve thousand children with ADD, Dr. Lubar has found that the basic issue for these children is their inability to maintain beta concentration states for sustained periods of time. He also found that these children have excessive theta daydreaming brain wave activity. Dr. Lubar found that through the use of neurofeedback, children could be taught to increase the amount of beta brain waves and decrease the amount of theta or daydreaming brain waves. They can train their brains to be more active.

The basic neurofeedback technique asks the patient—child, teen, or adult—to play games with their minds. The patient’s brain is hooked up to the computer equipment through electrodes placed on the head. The computer feeds back to the patient the type of brain wave activity it’s monitoring. For Type 1 (Classic ADD), the patient is rewarded for producing concentration or beta waves, and the more beta states he or she produces, the more rewards accrued. On the neurofeedback equipment, for example, a child sits in front of a computer monitor and watches a game screen that reflects the composition of his or her brain waves. If the child increases the “beta” activity and/or decreases the “theta” activity, the game continues. The game stops, however, when the child is unable to maintain the desired brain wave states. Children find the screen fun and many are able to gradually shape their brain wave patterns to a more normal one. From experience, clinicians know that this treatment technique is not an overnight cure. Children often have to do neurofeedback for thirty to forty sessions to see a significant benefit. In my experience with neurofeedback and ADD, many people are able to improve their reading skills and decrease their need for medication. Also, neurofeedback has helped to decrease impulsivity and aggressiveness. It is a powerful tool, in part, because we are making the patients part of the treatment process by giving them more control over their own physiological processes.

SPECT HELPS TO FOCUS NEUROFEEDBACK

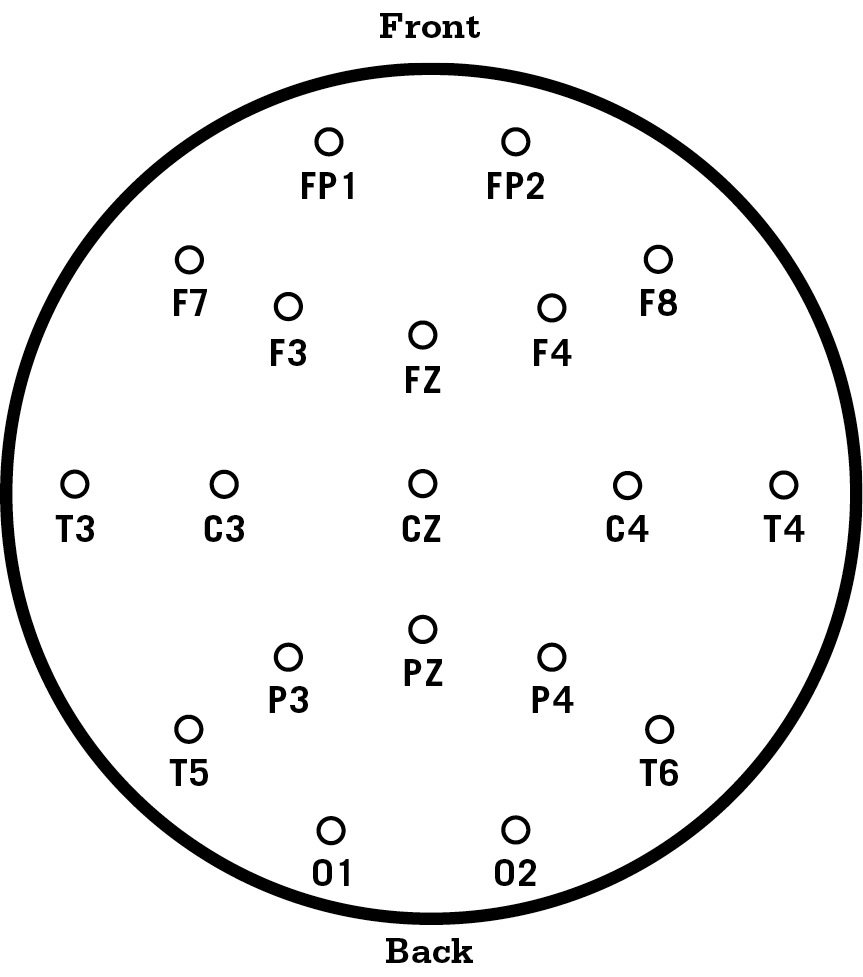

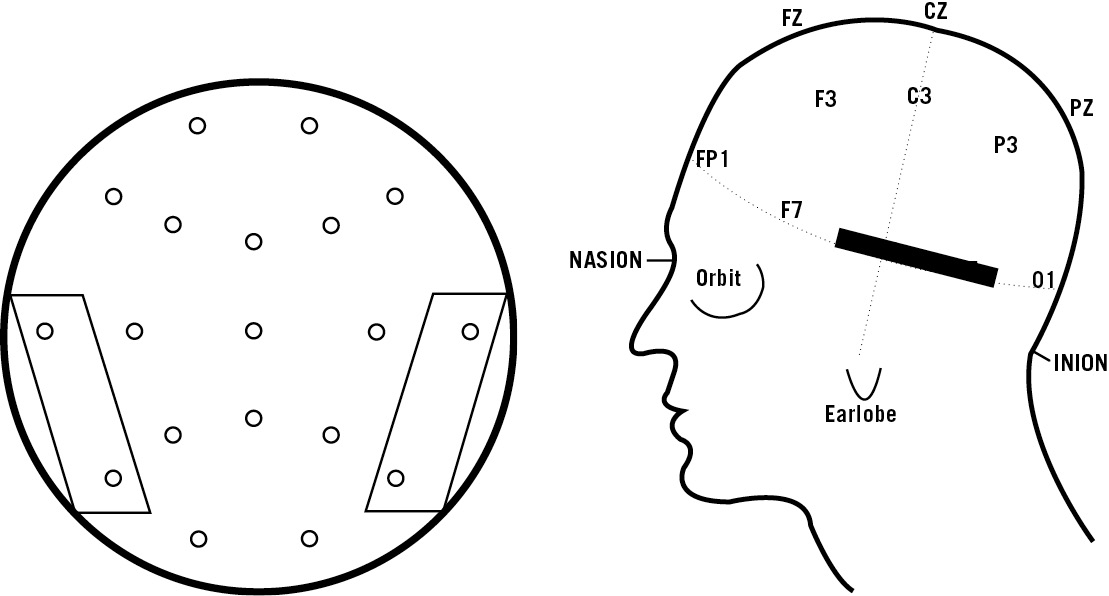

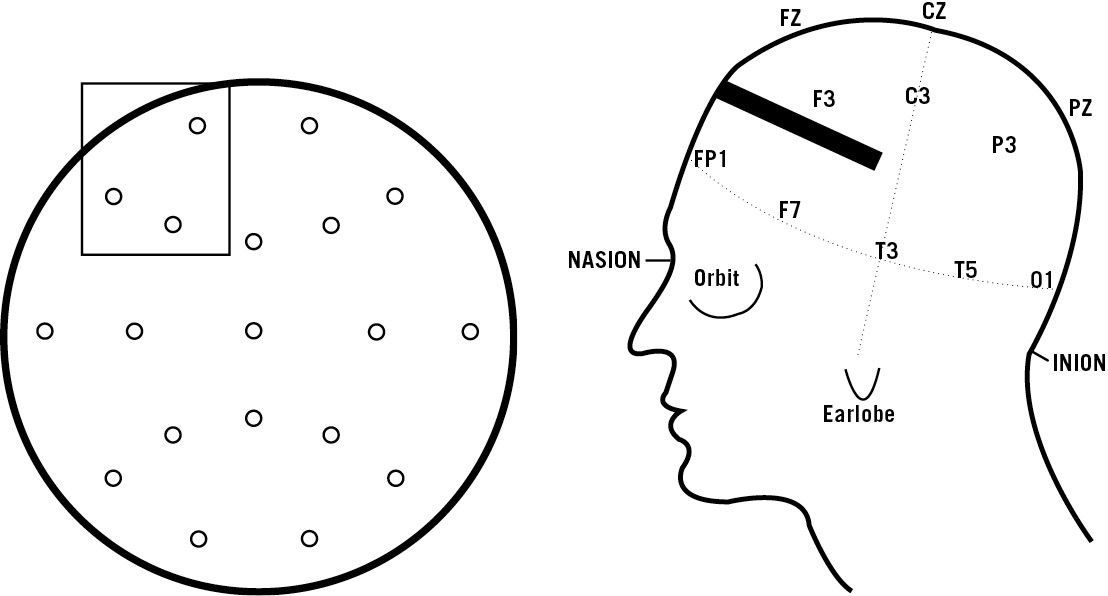

Through SPECT we have seen that ADD is a complex condition. Therefore successfully treating it requires more than one neurofeedback treatment. The figure below shows standard electrode placements. For people interested in neurofeedback, here is a list of training sites that we use in our office for the different ADD types. Share them with the neurofeedback professional in your area.

Joey, age seven, was brought to our clinic by his mother for hyperactivity, restlessness, impulse control problems, inattention, and distractibility. She heard about our work with neurofeedback and wanted an alternative to medication. Joey did neurofeedback twice a week for two years. After six months we began seeing significant changes, including less hyperactivity and longer ability to focus. In addition, his interest in reading significantly increased. After he stopped the neurofeedback, he continued to do well in school and at home. He maintained an exercise program and a higher protein, lower carbohydrate diet.

Figure 22-A, B (Top Down View, Left Side View)

Standard Electrode Placement Areas:

FP = frontal poles,

F = frontal lobe areas,

C = central areas,

P = parietal lobe areas,

T = temporal lobe areas,

O = occipital lobe areas.

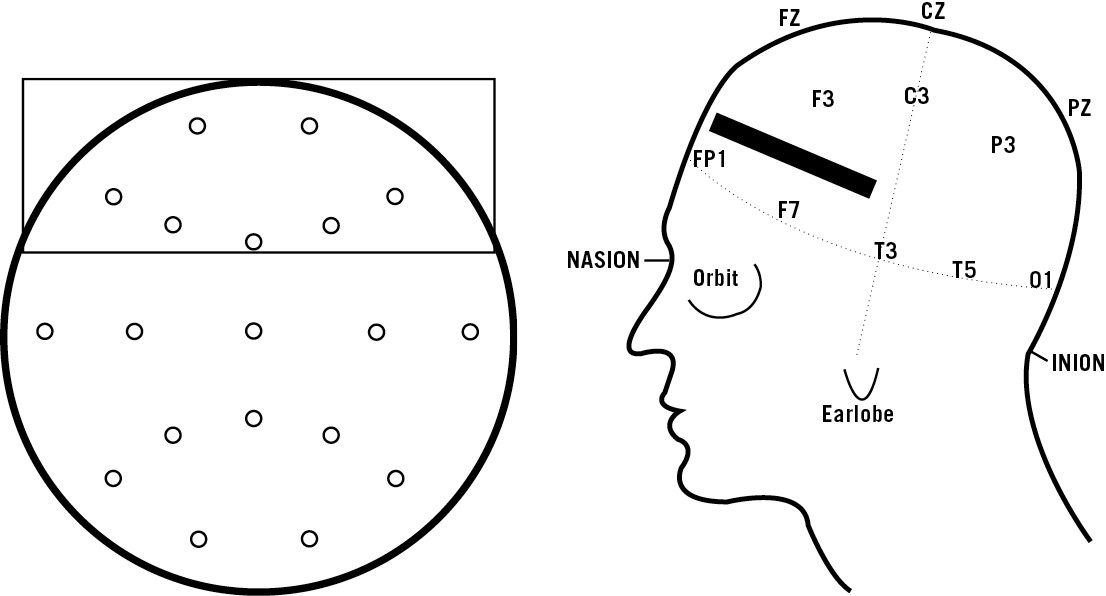

TYPE 3 (OVERFOCUSED) ADD

In Overfocused ADD there is excessive activity in the anterior cingulate gyrus. It is helpful to do the neurofeedback training over the front central part of the brain between FZ and CZ. This training helps people shift attention and feel more settled, less worried, and more compliant. It also enhances attention span. The training consists of enhancing high alpha activity (relaxed but focused).

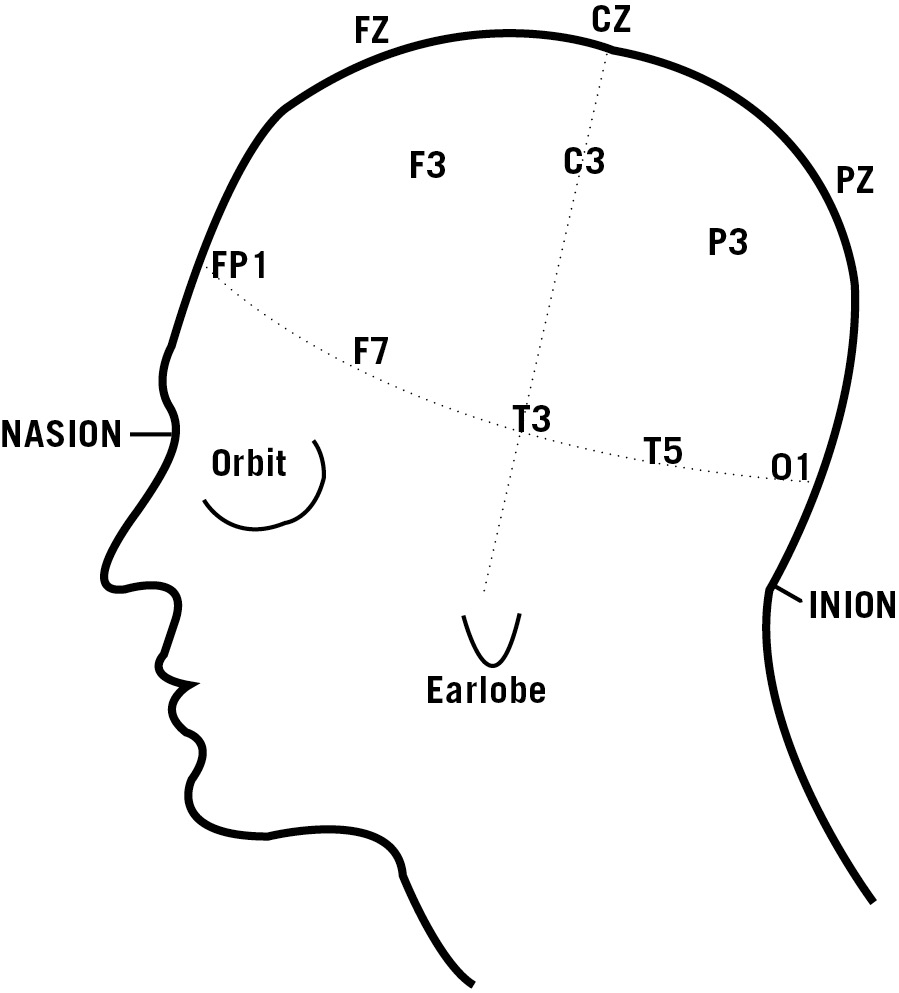

Type 1 (Classic) ADD and Type 2 (Inattentive) ADD

Classic and Inattentive ADD show decreased activity (excessive theta activity and poor beta activity) in the prefrontal cortex. It is helpful to do the neurofeedback training as close to the prefrontal poles as possible. The training consists of enhancing prefrontal beta activity and decreasing prefrontal theta activity.

Monica, age seventeen, came to the clinic for problems with anxiety, worrying, temper outbursts, poor school performance, and oppositional behavior. Her symptoms were much worse right before the onset of her menstrual period. She was in psychotherapy for two years, which seemed to help her temper problems but not her oppositional behavior or school performance. She had tried Prozac and Paxil with her family doctor but she did not like the side effects. Monica’s SPECT study showed marked increased activity in the anterior cingulate gyrus on both the rest and concentration studies. When she learned about neurofeedback, she liked the idea of learning how to control her own brain (sort of an “anterior cingulate control thing”). We did neurofeedback over her anterior cingulate gyrus twice a week for six months. In the first month she noticed less worrying. By the end of six months she felt more focused, less anxious, and overall more cooperative, an assessment her family validated. Nevertheless, she still had a hard time right before her period. I placed her on a small dose of St. John’s Wort (300 milligrams twice a day) which seemed to smooth out her menstrual mood swings.

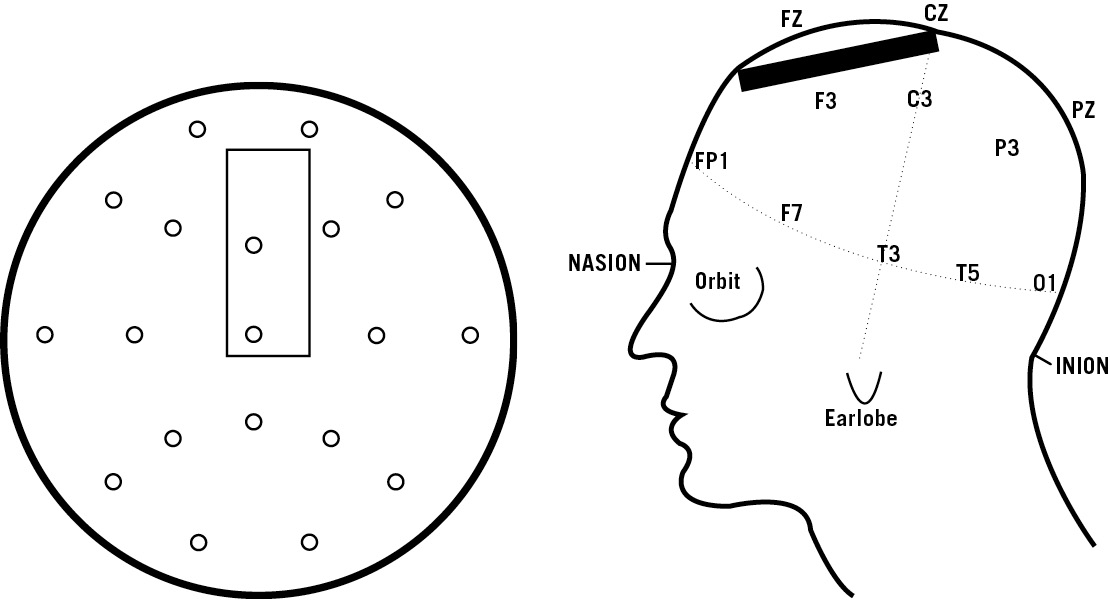

TYPE 4 (TEMPORAL LOBE) ADD

In Temporal Lobe ADD there is usually decreased activity (excessive theta activity) over the temporal lobes on one or both sides. Neurofeedback training over the affected temporal lobe seems to do the most good. We have seen this training help people have better mood stability, improved reading ability, and improved memory. The training consists of enhancing SMR activity and suppressing theta activity over the affected temporal lobe.

Marty, age fourteen, came to see us for temper outbursts, memory problems, poor reading skills, inattention, disorganization, and language problems (he had problems finding the right words and he often misunderstood people). His SPECT study showed significantly decreased activity in his left temporal lobe at rest. When he concentrated, the temporal lobe activity decreased even further along with his prefrontal cortex activity. He had had a poor response to Ritalin and the parents were hesitant to try an anticonvulsant medication. They wanted to try nonmedication options first, and they liked the idea of neurofeedback. We started neurofeedback training over Marty’s left temporal lobe. Within two months we noticed that his reading was starting to improve and his temper was better. After six months there was more mood stability. At that point, we started training his prefrontal cortex to be more active. He learned quickly. After eighteen months of training, Marty felt more in control of himself and much improved. In addition to training, he also exercised regularly and ate a consistent simple carbohydrate-free diet.

TYPE 5 (LIMBIC) ADD

In Limbic ADD there is decreased activity in the left prefrontal cortex and increased activity in the deep limbic areas. Since the deep areas are too deep in the brain to do neurofeedback training, we have found that teaching the patient to increase beta activity over the left prefrontal cortex has the most beneficial effect. This training helps improve focus and mood while decreasing negativity and negative thoughts. Of interest, a relatively new treatment for depression termed transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) uses powerful magnets to increase blood flow in this part of the brain. TMS has been shown to be very effective in resistant depression.

Robbie, forty-two, came to see me after he had lost his job and was nearly homeless. He was disheveled, lethargic, and demoralized. His history and SPECT studies clearly indicated Limbic ADD. His whole life he had underachieved in school and barely finished high school even though he had been tested as having an IQ of 120 (bright normal). He was disorganized, inattentive, and easily distracted. Teachers used to say that he did not live up to his potential and that he would do better if he tried harder. There were also teacher comments on his report cards that he should try to be more cheerful and positive. His SPECT study showed decreased left prefrontal cortex activity both at rest and with concentration and increased deep limbic activity on both studies.

He wanted to do neurofeedback instead of medication. Robbie trained his left prefrontal cortex to be more active. At first the training was very slow. It took him six months to be able to tune into his own brain wave patterns. But once he caught on to how to do the neurofeedback, the training went much faster. Within a year he felt better energy and he was more positive. He went to junior college and enrolled in an airline mechanics course. He got straight A’s in the course and was very proud of his abilities. He surprised himself by discovering a hidden artistic side, and he started bringing us sculptures and drawings. At the end of three years of neurofeedback training, he was significantly improved. Five years later he remains so.

TYPE 6 (RING OF FIRE) ADD

The neurofeedback protocol for this type of ADD is unknown at this time. Due to the diffuse nature of the cerebral hyperactivity, we doubt that one training site will work. It’s possible that multiple training sites will be helpful, such as SMR training over the parietal and lateral prefrontal areas and high alpha training over the anterior cingulate area, but it is yet to be determined.

TYPE 7 (ANXIOUS) ADD

In Anxious ADD we often see excessive beta activity in the right prefrontal cortex. The neurofeedback protocol for this type of ADD is to calm this part of the brain, but not too much, so we do high alpha training over this area.

Audio-Visual Stimulation (AVS)

A similar treatment to neurofeedback is something called Audio-Visual Stimulation. This technique was developed by Harold Russell, Ph.D., and John Carter, Ph.D., psychologists at the University of Texas, Galveston. Both Drs. Russell and Carter were involved in the treatment of ADD children with neurofeedback, but they wanted to develop a treatment technique that could be available to more children. They based their technique on a concept termed “entrainment,” in which brain waves tend to pick up the rhythm in the environment around them. They developed special glasses and headphones that flash lights and sounds at specific frequencies that help the brain “tune in” to be more focused. Patients wear these glasses for thirty to forty-five minutes a day.

I have tried this treatment on a number of patients, with some encouraging results. One patient, who developed tics on both Ritalin and Dexedrine, tried the glasses for a month. His ADD symptoms significantly improved. When he went off the Audio-Visual Stimulator, his symptoms returned. The symptoms again subsided when he retried the treatment.

Trigeminal Nerve Stimulation (TNS)

Another potentially interesting and helpful treatment for ADD is something called Trigeminal Nerve Stimulation (TNS). It is a noninvasive treatment already approved in Europe and Canada for refractory epilepsy and major depression. A study of twenty seven- to fourteen-year-old children presented at the 2013 Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association reported that use of TNS resulted in robust improvements in ADD symptoms and executive function, as well as on computerized testing of cognitive measures. Ian Cook, M.D., of UCLA said there is great excitement over the potential of this treatment.

“The trigeminal nerve is one of the twelve cranial nerves, and stimulation of this one nerve can enhance functions such as attention, emotional processing, concentration, anxiety, and seizure generation,” Dr. Cook said. Using positron emission tomography (PET) scans, these researchers had previously shown that electrical stimulation of trigeminal nerves using an adhesive patch on the forehead attached to a stimulator resulted in increases in blood flow within sixty seconds in areas such as the frontal lobes.

During studies of the system in refractory epilepsy and treatment-resistant depression, Dr. Cook said, they noticed that patients also reported that they were able to focus their attention better, which led to current study. TNS is not yet approved in the United States, but may be soon, and is worth watching.

Neurofeedback, AV stimulation, and TNS hold significant promise as non-pharmacological treatments for ADD.