3

Civic progress

By the mid-16th century, Cambridge had begun to look more than just a modest market town. A Paving Act in 1544 gave promise of less muddy streets and a memorable visit by Queen Elizabeth I in 1564 prompted a general sprucing up. In the same year the Chancellor was empowered to license alehouses, cutting their number from 80 to around 30. In 1573 the university was granted its own coat of arms. The town followed suit two years later, with a design featuring Magdalene (Great) Bridge, the ancient castle, three ships and the rose and fleur-de-lys, indicating royal favour. Pointedly, there are no references to the presence of the university. The ruined remains of former religious houses were replaced by new colleges – Emmanuel and Sidney Sussex – and the decayed Gonville Hall was revived. In 1604 the university was invited to send two Members to Parliament. The town meanwhile campaigned for promotion to the status of city but the university, fearing the ‘power and authority which the very bare title of a city will give unto them’ scotched that by backstairs appeals to its friends and alumni in high places. Both Town and Gown remained, however, vulnerable to capricious Nature in the shape of plague, with more than 400 dying in 1610, and another very severe outbreak in 1630. In 1666, the year after London’s Great Plague, more than 800 were carried off, one in eight of the town’s population.

Fires of faith

Henry VIII repudiated the authority of the Pope to become head of the Church in England, yet died believing himself a good Catholic. His three children set the country on a religious switch-back, which ultimately created a Church of England, basically Protestant in its doctrines but, for Puritans, still too Catholic in governance and worship.

Henry’s precociously pious son Edward VI pushed England towards Protestantism. In 1549, when the first edition of Archbishop Cranmer’s Book of Common Prayer came into use, Cranmer invited the German Protestant theologians Martin Bucer (1491–1551), an ex-friar married to an ex-nun, and Paul Fagius (1504–1549), to Cambridge as Regius Professor of Divinity and Regius Professor of Hebrew, respectively. Providence, however, had other plans. Fagius died of plague almost immediately. Bucer died in 1551 and was buried in the chancel of Great St Mary’s. None of this had been good for university recruitment. Bishop Latimer warned Edward VI that ‘there be none but great men’s sons in colleges and their fathers look not to have them preachers’.

Passionately Catholic Mary (r.1553–58) led a sustained campaign to reinstate Catholicism. Mass was re-established, all but three Cambridge heads of houses dismissed, Protestant activists driven into exile and searches made for suspect writings and incriminating letters. Visitors to Oxford now orientate themselves from the Victorian Gothic ‘Martyrs’ Memorial’, honouring the deaths in 1555 of Bishops Latimer and Ridley (c.1500–1555) and Archbishop Cranmer, burnt for refusing to renounce their Protestant convictions. These ‘Oxford Martyrs’ were, all three, Cambridge men.

In 1557 Fagius and Bucer were posthumously tried and condemned for heresy and their coffins dug up and burnt in the market place, while heretical books were flung on the flames. However, following Elizabeth I’s accession in 1558 their degrees and titles were restored and Bucer’s memory was honoured with a second funeral in 1560, memorialised with a floor plaque to the right of the altar of Great St Mary’s.

Caius College

What is now the fourth largest college is usually referred to as Caius (pronounced ‘Keys’), the Latinised form of the name of its re-founder Dr John Keys or Kay(e) (1510–1573). Caius went to Gonville Hall as a fount of the new ‘Greek learning’. Intended as a theologian, by 23 he was Principal of Fiswick’s (Physwick) Hostel but left in 1539 to study abroad. In Padua, Europe’s leading centre of medical education, he qualified as a doctor under the founder of modern anatomy, Andreas Vesalius (1514–1564). Returning, Caius lectured on anatomy, became royal physician to Edward VI, Mary and Elizabeth and served nine times as President of the Royal College of Physicians. The leading expert on the Roman medical authority Galen, Caius also wrote a definitive account of sweating sickness and as London’s leading practitioner became very rich.

In 1557 Mary authorised Caius to re-found his old college, Gonville Hall, which, crippled by the royal confiscation of Physwick Hostel, was in danger of being swallowed up by the cuckoo Trinity. Curiously for a medical man, Caius’ articles of governance at Gonville excluded ‘the deaf, dumb, deformed, chronic invalids and Welshmen.’ The last may have been the result of a clerical error – ‘Wallicum’ rather than perhaps the intended ‘Gallicum’ – i.e. Frenchmen. In that same year, Caius conducted, at Gonville Hall, Cambridge’s first recorded dissection of a human body.

In 1559, following the death of the Master of what was henceforth Gonville and Caius College, Caius was persuaded to succeed him. Autocratic and cantankerous, Caius sacked several fellows and was accused of being a crypto-Catholic. As adjudicator, Archbishop Parker found ‘both parties … not excusable from folye’, criticising Caius for ‘overmoche rashness for expelling felowes so sodonly’. He conceded that ‘the contemptuose behaviour of these felowes hath moch provoked him’ and concluded realistically that ‘founders and benefactors be very rare in these days … Scholars controversies … many and troublouse’. A prolific, and respected, medical author, Caius ventured into history to prove Cambridge more ancient than Oxford. Ecclesiastical historian Professor C N L Brooke has dismissed Caius’s De Antiquitate Cantabrigiensis Academiae (1568) as ‘a miracle of perverted learning, based on a magnificent list of irrelevant authorities.’

Caius’s commitment to the college manifested itself in a substantial building programme, enlarging the Master’s lodging and creating Caius Court (1565–7) as student accommodation. Its design drew on his medical expertise to pioneer the three-sided courtyard, an open side deemed essential for air circulation against damp, infectious vapours. This novel idea was to be taken up at Emmanuel and Sidney Sussex, Trinity, Trinity Hall (Library Court), Peterhouse (Entrance Court), Pembroke (Ivy Court) and Jesus (First Court). Much later it was applied to the main court at King’s (1824–8), Gisborne Court at Peterhouse (1825–6), New Court at St John’s (1826–31), Memorial Court at Clare (1923–4), North Court at Jesus (1963–4) and the Wolfson Flats at Churchill (1965–8).

Caius’s major architectural legacy was, however, the construction (to his own designs) of a sequence of fantastical gateways symbolising the successful progress of a model student: he would enter via the modest Gate of Humility (1565), pass through the Gate of Virtue (1565–7) and emerge through the triumphal arch of the Gate of Honour (1573–5) to proceed to the Old Schools and take his degree. (A fourth gate in Tree Court, opening onto a lavatory, is referred to unofficially as the Gate of Necessity.) The original Gate of Humility was removed to the Master’s garden. On Trinity Street its 19th century replacement still bears the injunction ‘Humilitatis’. The Gate of Virtue, linking Tree Court to Caius Court, is Gothic on one side, classical on the other. The extravagant Gate of Honour now leads rather incongruously into constricted Senate House Passage. Pevsner observes that this gate, smallest of the three, is absurdly out of scale for the complexity of its design and decoration – ‘illustrations make one expect a building twice the size’. See what you think of one of the most photographed architectural details in Cambridge.

Caius’s memorial in the college chapel carries an epitaph as terse as even Latin gets – Fui Caius (‘I was Caius’) – complemented by Vivit Post Funera Virtus (‘Virtue Lives Beyond the Grave’) – the very words chosen by Caius for Thomas Linacre (c.1460–1524), first President of the Royal College of Physicians, whose tomb in St Paul’s Cathedral he paid to refurbish.

Caius was succeeded by the lawyer Thomas Legge (1535–1607). Another Norwich man, Legge also fell out with his juniors and was accused of favouring Yorkshiremen and Catholics, embezzlement, and disturbing students with rowdy music, none of which stopped him from serving as Regius Professor of Civil Law, Vice-Chancellor (twice) and Justice of the Peace for Cambridge. He also wrote a play in Latin about Richard III.

Parker’s principles

An early but cautious Protestant, learned scholar, potent preacher and conscientious educator, Matthew Parker (1504–1575) was successively chaplain to the ill-fated Anne Boleyn (1501–1536) and then to Henry VIII, who ordered his election in 1544 as Master of his old college, Corpus Christi. Parker immediately reordered its affairs, organising inventories of assets and properties and commissioning a college history. Scrupulously conscientious, he yet remained, like his close friend John Caius, a loyal member of the Norwich and Norfolk university mafia, endowing scholarships and fellowships limited to candidates from his own city and county and giving them preference in the allocation of rooms, the reservation of books and even bedding.

Gonville and Caius College

Despite his Protestantism, Parker was sufficiently traditionalist to keep the college as Corpus Christi, despite the Papist overtones of the name. Even so, he was one of Mary’s victims, forced to live on the run until her death in 1558. Parker then pleaded with Elizabeth to allow his return to Cambridge, but loyal to the memory of her mother, Anne Boleyn, the Queen instead persuaded him to become the second Protestant Archbishop of Canterbury in 1559, tasked with enforcing the beliefs, worship and Bible of the new ‘Church of England’.

However, Parker remained devoted to both Corpus and Cambridge. In 1568 Elizabeth authorised him to recover library holdings scattered by Henry’s dissolution of religious houses. Ostensibly the aim was to copy precious documents but hundreds were never returned, and the bulk of the collection, 433 manuscripts, went to Corpus. The manuscripts form an invaluable historical record. Almost 40 predated the Norman Conquest, with highlights including the earliest extant editions of the Dark Age chronicler Gildas, Asser’s biography of Alfred the Great, a ninth-century dictionary defining more than two thousand Anglo-Saxon words, and autographed letters of Luther, Calvin, Anne Boleyn and Edward VI. The Parker Library, now with 550 manuscripts, went online in 2010 (www.parkerweb.stanford.edu). Visit the site to see the oldest illustrated Latin Gospel in existence – the sixth-century Augustine Gospels on which the Archbishops of Canterbury still take their oath of office. It has been in England longer than any other book.

In 1570 Parker endorsed the new statutes which would govern the university until the reforms of the mid-Victorian period. Largely with a view to curbing Puritan extremism, these enhanced the powers of the Vice-Chancellor and Heads of Colleges, enabling them to influence most appointments, and in effect, authorising them to interpret the university’s statutes as they chose. These changes were highly unpopular with the radical element amongst the junior fellows, but were enforced despite their resistance.

One of Parker’s last gifts to Cambridge was one of its earliest pieces of town planning – the creation in 1574 of University Street, running from the Old Schools to the west door of Great St Mary’s. Cutting through a jumble of alleys, houses and hostels, this impressed contemporaries but has now completely disappeared. The re-naming of Emmanuel Back Lane to Parker Street in the 18th century may be a tribute to the Archbishop – but Parker’s Piece has nothing to do with him; in 1613 Trinity College swapped the 25 acres it owned in Barnwell Field for the area, then owned by the town and known as Garret Hostel Green, where Trinity would expand its buildings. At that time Trinity’s Barnwell holding was leased to college cook Edward Parker – hence Parker’s Piece.

Perne’s pragmatism

In the theological maelstrom of the 16th century, few proved more buoyant than Andrew Perne (1519–1589). A fellow of St John’s and Queens’, Master of Peterhouse, canon of Windsor and Dean of Ely, Perne, serving five times as Vice-Chancellor under Protestant Edward VI, Catholic Mary and Anglican Elizabeth, was variously both for and against the adoration of images, the doctrine of transubstantiation and the authority of the Pope. He also organised the desecration of the bodies of Bucer and Fagius, then presided over their reinstatement, inspiring a new verb, ‘to perne’, meaning to have a threadbare garment turned. Perne seems to have shared the joke, commissioning a weathervane for St Peter’s church marked with his initials, AP – variously interpreted to mean A Protestant, A Puritan or A Papist. Miserly but hospitable, sycophantic but eloquent in repartee, Perne was constant in loyalty and generosity to the college and the university, building Peterhouse library and bequeathing to it and the University Library the contents of his own fine collection.

Printing and publishing

The first printer in Cambridge was Johann Lair of Siegburg, who anglicised his name to John Siberch. Arriving in 1521 with his own press, he printed ten different titles, but whether for professional or personal reasons, returned to Germany in 1522. In 1534 Henry VIII granted the university the right to print books, but it was not until 1584 that university printer Thomas Thomas published the first titles – treatises on the Holy Communion, a Latin dictionary and an edition of Ovid. A volume by the Puritan preacher, Walter Travers (c.1548–1635) of Trinity, put forward Presbyterian views critical of the new Anglican church settlement. Archbishop Whitgift wrote a weary ‘I told you so’ letter to William Cecil, the Chancellor of the university – ‘Ever since I heard that they had a printer at Cambridge, I did greatly fear that this and such like inconveniences would follow.’ Whitgift ordered all copies of the offending volume destroyed and as a further precaution, banned the printing of any book not authorised by himself or the bishop of London. In 1586 the Court of Star Chamber grudgingly agreed that Cambridge and Oxford might each have one press only, with all other printing to be concentrated in London, under its watchful eye. Despite these less than encouraging origins, Cambridge University Press now claims to be the oldest publishing house in continuous existence in the world. Its most important early production was the ‘Geneva Bible’ of 1591, used by Shakespeare and the early Puritan settlers of New England. Later titles included the works of Milton and Newton.

Out of ruins

Emmanuel College was founded by Sir Walter Mildmay (1523–1589), whose Essex family had done well out of the dissolution. Mildmay attended Christ’s, leaving without a degree, but as a Gray’s Inn lawyer he specialised in property and auditing, later becoming Treasurer of Elizabeth I’s household and Chancellor of the Exchequer. In 1583 Mildmay paid Cambridge’s former Dominican friary £550 for a new college to be erected (1584–8), not, its founder warned, to provide ‘a perpetual abode for fellows’, but to breed men of learning for ordination to go out into the world and change it. The founding statutes bade members to avoid idle gossip and to watch over and, if necessary, reprove each other’s behaviour.

Laurence Chaderton (c.1536–1640) was almost 50 when he became Emmanuel’s first Master, forced into accepting the task (and a miserly stipend of £15 a year) by Mildmay’s insistence that ‘If you won’t be Master, I won’t be Founder.’ Chaderton held the post for 38 years. His grave in the college chapel claims he eventually died in his 103rd year.

When the Queen remarked challengingly, ‘Sir Walter, I hear you have erected a puritan foundation’, Mildmay replied with studied ambiguity – ‘No, madam, far be it from me to countenance anything contrary to your established laws but I have set an acorn, which when it becomes an oak, God alone knows what will be the fruit thereof.’ Half a century later the financial legacy of one of Mildmay’s ‘fruit’ founded Harvard College.

As the first new college in Cambridge since the Reformation, Emmanuel paved the way for the foundation of Sidney Sussex College in 1596, established on the former site of the Franciscan friary. The college was established with the £5,000 legacy of Frances Sidney, Countess of Sussex, who died in 1589 before her project could be realised. Her executors, John Whitgift (c.1530–1604), Archbishop of Canterbury, and Sir John Harington (1561–1612), battled through financial complications to bring it to fruition. Harington – wit, charmer and godson of Elizabeth I – was twice banned from court for his risqué writings and is now remembered as the inventor of the flushing toilet. He once wrote that Cambridge was ‘the Nursery of all my good breeding’ – tongue in cheek?

Sidney Sussex was the first Cambridge college to open its fellowships to Scotsmen and Irishmen, though not, as it were, fresh from the branch. Celtic candidates had to have been in Cambridge for at least six years. And if Emmanuel was an acorn, Sidney Sussex was initially little more than a seed, consisting of a Master, three fellows and four scholars.

The topographer William Camden acknowledged the significance of ‘the other University of England’ and more particularly its 16 colleges – ‘sacred mansions of the Muses, wherein a great number of learned men are maintained and wherein the knowledge of the best arts and the skill in tongues so flourish, that they may rightly be counted the fountains of literature, religion, and all knowledge whatsoever, who right sweetly bedew and sprinkle, with most wholesome waters the gardens of the Church and Commonwealth’. Camden made his general point firmly, not to say floridly, enough but he could not know that by 1640, 2.5% of the male population was attending university, a figure not to be exceeded until the 1930s.

The undergraduate population, like the society from which it came, was hierarchical in composition. As the Renaissance made a veneer of learning a social necessity among the aristocracy, the proportion of young noblemen attending – rather than studying at – Cambridge increased. In return for hefty fees they usually dined with fellows and were relieved of the squalid obligation to take examinations. However, most undergraduates were ‘pensioners’, obliged both to pay fees and take exams. At the bottom of the heap were ‘sizars’ working their way through college by waiting on their better-off fellows at table, clearing the chamber pots in their rooms, helping out in the library or labouring in the college grounds.

Cambridge and Court

Elizabeth I built up something of a reliance on Cambridge men, and her favourites came to include the Archbishops Edmund Grindal (c.1519–1583) and John Whitgift; Dr John Dee (1527–1608), her personal astrologer; Sir Francis Walsingham (c.1532–1590), her self-appointed head of security; his master code-breaker and forger, Thomas Phelippes, alias Peter Hollins (1556–1625); the poetic courtier Edmund Spenser (c.1552–1599); her fated favourite, Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex (1566–1601); Sir Walter Mildmay; Sir Thomas Gresham (1519–1579), her financial guru and most trusted adviser; and William Cecil (1520–1598), Lord Burghley, Chancellor of the University for almost 40 years.

The career of Thomas Nevile (c.1548–1615) illustrates the interaction between academic and ecclesiastical advancement and royal patronage. Initially at Pembroke Hall, Nevile became Master of Magdalene, a chaplain to Elizabeth I and Vice-Chancellor, also enjoying incomes from appointments at the cathedrals of Ely, Peterborough and Canterbury, as well as country rectories where the actual parish duties were performed by a curate as his deputy. Appointed Master of Trinity College – a post created by royal decree – Nevile undertook a dramatic building programme, which is his chief legacy. The surviving buildings from Kings Hall, Michael House and the Physick Hostel were demolished in 1597 to make way for the Great Court (1597–1605), which is the largest in either Cambridge or Oxford. Nevile himself stumped up £3,000 a year over seven years (1602–8) to pay for a complementary new hall, big enough to stage plays in. The largest in Cambridge, it is exactly the same size as Middle Temple Hall in London (103ft × 40ft × 50ft). He then paid for what is now Nevile’s Court (1614), which featured the novelty of two parallel cloistered ranges – and still had enough left over to bequeath to the college ‘a bachelor’s bounty’.

The Marlowe mystery

Playwright Christopher Marlowe (1564–1593) was not yet 30 when he died, stabbed above the eye in a tavern brawl in Deptford. Whether he was deliberately ‘eliminated’ on the order of the government remains unclear. Marlowe was probably recruited into Walsingham’s secret service while still at Corpus Christi, which he entered in 1581. After taking his BA in 1584 Marlowe was absent for such prolonged periods it became uncertain whether he would proceed to MA – until the Privy Council directed the university authorities to grant the degree as Marlowe had been employed ‘on matters touching the benefit of his country’, possibly infiltrating circles of English Catholics abroad or liaising with Protestant rebels in the Netherlands.

Marlowe may well have begun writing Dido, Queen of Carthage, and possibly even the first part of Tamburlaine the Great, while still at Cambridge. Mixing in criminal as well as theatrical and courtly circles in London, Marlowe enjoyed brief but brilliant success with The Jew of Malta, Dr Faustus and Edward II. A professed atheist and homosexual with a penchant for violence, he was probably protected by Walsingham until the latter’s death in 1590, after which Marlowe’s dissolute lifestyle virtually guaranteed his untimely end. The only generally acknowledged portrait of Marlowe, painted by an unknown artist in 1585, was rediscovered in 1952 among a pile of builder’s rubble during renovation work on the Master’s Lodge at Corpus. The baby-faced genius stares out, half-smiling, beneath an enigmatic motto – Quod Me Nutrit Me Destruit (What Nourishes Me Destroys Me).

A Cambridge character

Thomas Hobson (c.1544–1631) inherited a cart and eight horses and went on to build a fortune from his stable by operating a carrier’s service to London and hiring out horses. Hobson ensured that each of his mounts was properly rested and fed. His insistence that they were only available in strict rotation faced clients with accepting ‘Hobson’s Choice’ – or none. As a carrier Hobson provided wheeled transport essential for those who could not ride (women, children, the aged and infirm) and for bulky baggage, like scholars’ books and trunks. He also had a prestigious sideline conveying ‘great vessels of fish’ (tanks in which live fish were kept fresh) ‘for provision for his Majesty’s household.’

Hobson’s business acumen also brought him extensive properties, including no fewer than five manors. His public spirit led him to serve as mayor and in 1628 to give the city the site for ‘Hobson’s Workhouse’, more notoriously known as the ‘Spinning House’, where the indigent were set to spin yarn in return for their keep. Located on the south side of St Andrews’ Street, it was demolished in 1901. Hobson House now marks its site.

Between 1610 and 1614 the Cambridge New River was built, at the joint expense of town and university, to bring fresh water from Nine Wells near Trumpington – a parallel to the exactly contemporary New River project to supply London. Hobson’s will provided for the perpetual maintenance of this work. A handsome hexagonal stone conduit, with shell niches, strapwork ornamentation and an ogee cupola, originally stood on Market Hill in 1614, but is now on Trumpington Street, opposite Scroope Terrace. Hobson was buried in his own parish church, St Benet’s, sufficiently renowned for Milton to write two humorous epitaphs in his honour. He is also remembered in the names of Hobson’s Passage and Hobson Street.

Legacies of learning

A Caius man from the age of 17 until his death, Stephen Perse (1548–1615), as a physician and financier, built up a Cambridge property portfolio sufficient to endow six fellowships and six scholarships at Caius and help fund part of what is now Tree Court. The rooms of the original Perse Building (1617–18) were each built with a ‘convenient Studdie’, an early recognition that scholarship might require silence and solitude. The bulk of Perse’s estate, however, was for a grammar school for 100 pupils, initially housed in former buildings of the Austin Friars, in what is now appropriately called Free School Lane. Decayed by 1800, the Perse School’s main room was used as a picture gallery before the school was successfully revived in the 1840s and transferred to Hills Road in 1888. The university bought its original site for £12,500 for an engineering laboratory, and it is now the location of the Whipple Museum of the History of Science: the original Jacobean hall, with its hammerbeam roof, survives. Distinguished Perse alumni include Reuben Heffer and F R Leavis. The monument to Perse in Caius’ chapel has been attributed to Maximilian Colt (d.1641), sculptor of the monument to Elizabeth I in Westminster Abbey. Another statue of Perse, holding a model of his school, can be seen in Tree Court at Caius. Perse also paid for the road now known as Maids’ Causeway, and almshouses in Newnham Road.

John Harvard (1607–1638) was born in Southwark, by London Bridge; his mother, having married three times, accumulated considerable property, to her son’s ultimate benefit. After attending Emmanuel College from 1627–35, Harvard married in 1637 and migrated, settling at Charlestown, Massachusetts, where his wealth and learning immediately made him a man of standing and influence. He died, however, in 1638, childless, leaving half his considerable estate to a proposed college for which £400 had already been pledged, and also bequeathing his library of 329 volumes, probably the largest in the colonies at that time. Harvard’s bequest prompted construction to begin and in 1639 the college was named in his honour and its site, Newtown, renamed Cambridge. John Harvard is commemorated by a stained-glass window in the chapel of Emmanuel College. As there was no surviving portrait the Victorian designers were told to make him look like John Milton but with longer hair.

Puritan pioneers

John Harvard was one of tens of thousands who left England in the ‘Great Migration’ of the 1630s, fleeing the rule of Charles I, who governed without Parliament and supported the anti-Puritan regime of his Archbishop of Canterbury, William Laud (1573–1645). Cambridge men provided the intellectual core of this colonising movement. William Brewster (c.1560–1644), who had studied at Peterhouse, led the way as one of the original Mayflower ‘pilgrims’ in 1620, followed by William Blackstone (1595–1675) an alumnus of Emmanuel, who in 1623 founded what became Boston. Thomas Hooker (1586–1647), a graduate of Queens’, established the first church in Cambridge, Massachusetts and founded Hartford, Connecticut. Of the 140 graduates known to have emigrated to the American colonies before 1645, 102 came from Cambridge. Thirty-five of these were from Emmanuel College alone, outnumbering the entire Oxford contingent of 32. A further 13 were from Trinity, including the first ‘Overseer’ of Harvard, John Cotton (1585–1652). The president-designate, Nathaniel Eaton (1610–1674), another Trinity man, was sacked for thrashing students and embezzling funds, but the situation was rescued by the first actual holder of the office of President, learned, pious Henry Dunster (1609–1659) a graduate of Magdalene. John Eliot (c.1604–1690), the ‘apostle to the Indians’, was a Jesus man, as was, much later, East Apthorp (1733–1816) a signatory to the Declaration of Independence. (Another signatory was Thomas Lynch of Caius.) Peter Bulkeley (1583–1659) of St John’s was a founder of Concord, New Hampshire. John Robinson (c.1576–1625), pastor to the Pilgrim Fathers, studied at Corpus. Pembroke contributed Roger Williams (1604–1683), founder of Rhode Island. In 1654 Pembroke received John Stone, the first American to become a fellow at a British university.

One of the earliest Harvard graduates was George Downing (1623–1684), who became a spy for Cromwell, then a turncoat to the Royalists and a secret agent against the Dutch. He received some land as a reward, on which he built Downing Street in Whitehall, where British prime ministers reside at No 10. The dubious fortune he amassed ultimately went to found Downing College.

Creeping classicism

Cambridge buildings of the early 17th century combined creativity with confusion as old-fashioned late Gothic oriels and ogees were thrown together with pediments and balustrades inspired by the models of the Classical world.

When St John’s decided to build a new library it opted for a ‘retro’ Gothic look which initially bemused John Williams, Bishop of Lincoln (1582–1650), Lord Keeper of the Great Seal, who was paying for it. Bishop Carey (d. 1626) reassured him on behalf of the college that ‘men of judgment liked the best the old fashion of church windows, holding it the most meet for such a building.’ Pevsner notes the significance of this deliberate historicism – ‘here for the first time Gothic forms were used self-consciously … There can be few examples of a true Gothic Revival in the country (or, indeed, any country) earlier than this.’ One hundred feet long, the library, built in 1624, did feature one recognisable novelty – bookcases attached to the walls, rather than freestanding. At the top of the oriel gable of the river elevation are the initials ILCS – Iohannes Lincolnensis Custos Sigilli – John of Lincoln, Keeper of the Seals.

The new chapel at Peterhouse, by contrast, built between 1628 and 1632, during the Mastership of Matthew Wren (1585–1667), uncle of Christopher Wren, featured a mixture of motifs, including a classical pediment. Rawle considers it ‘one of the finest buildings of its date in Cambridge and certainly the most striking at Peterhouse.’ The classical cloisters at the west end were a later addition.

At Clare the rebuilding of what became the Old Court began in 1638 but ended abruptly in 1642 with the outbreak of civil war, by which time only the east and south ranges had been completed. Rebuilding was not recommenced until 1669 and only completed in 1715, with balustrades added in 1762. Despite taking 77 years to accomplish, Pevsner, who devotes more than two entire pages to it, considered it ‘more of one style than any other 17th century work in Cambridge’; the first totally classical court in the university. The south range, viewed from the lawns of King’s and the west range, viewed from across the river, are breathtaking in their repetitive orderliness. In 1639–40 Clare also built the first bridge in Cambridge in a classical mode.

Pevsner’s palm is, however, reserved for the ‘New’ (now Fellows’) Building at Christ’s (1640–3), as ‘the boldest building of these years … one of the most original of its date in England’. Rawle likewise judges it the first ‘almost purely’ classical building in Cambridge, notably for pioneering a new style of cross window, later much imitated. Lacking a munificent benefactor, the college wrote – in Latin – a circular letter to alumni in which it expressed itself ‘confident that you will not let down the honour of those buildings in which you drew the seeds of that virtue and erudition that still adorn you as a man.’ It evidently worked, with alumni raising some two-thirds of the budget of more than £3,600. Three, rather than the normal two, storeys high, with dormers inserted in the roof space and fronted by a balustrade, it was built quite independent of the previous court and featured alternating triangular and segmental pediments above its principal windows. Strongly symmetrical, it encapsulated what the Oxford-educated dilettante John Evelyn crisply called ‘exact architecture’.

The gardens of the religious houses of medieval Cambridge provided herbs for kitchen and sanatorium, fruit for the table and space for quiet contemplation. The monks of the Benedictine house which stood where Magdalene College now is were expected by the rules of their Order (Ora et Labora – Pray and Work) to labour daily in its gardens. The gardens of Emmanuel and Sidney Sussex are also on land once tilled and tended by monks. Peterhouse, King’s Hall and Pembroke all cultivated the saffron crocus, a highly valued crop, used for both cooking and dyeing – 4,000 blooms were required to produce a single ounce. As the university spawned overcrowded lodging houses and the town was interlaced with squalid alleys, college gardens became refuges for informal teaching and recreation. As colleges developed their individual identities and a parallel sense of rivalry, gardens became objects of pride – and expenditure. In 1532 Queens’ decided that its President should have his own garden ‘for frute’ and ‘to walk in’. In 1575 the same college built a framework for a vine in the Fellows’ garden and bought in 1,000 honeysuckles.

David Loggan’s views of Cambridge show Pembroke had a bowling green and sedate walks but that most of its gardens were given over to productive purposes – an orchard with espaliered fruit trees, ponds for carp and pike, hives for bees and beds for fruit, vegetables and herbs. By then college gardens were being enjoyed by visitors as well as residents. Celia Fiennes remarked that ‘St John’s College Garden is very pleasant for the fine walks, both close shady walks and open rows of trees and quickset hedges, there is a pretty bowling green with cut arbours in the hedges … Clare Hall is very little but most exactly neat; in all parts they have walks with rows of trees and bridges over the river and fine painted gates into the fields’.

Generations of undergraduates have exploited college gardens as potential weak points in the systems of security and surveillance. In 1754 the future Rev Dr John Trusler (1735–1820), strolling round Emmanuel College ‘perceived a key left in the gate … through which the gardener was wheeling dung’. Trusler seized his chance, paid a nearby smith to make a template of it, returned the original undetected, and had his own duplicate made, after which ‘everyone wished to become my friend,’ so that they could evade the normal evening curfew of 9:00 p.m. in summer, or 6:00 p.m. in winter.

The 18th century ‘Grand Tour’ exposed English gentlemen to continental gardening, and the emerging cult of ‘the picturesque’ awakened an appreciation of natural landscape. Botany likewise emerged as a science and an essential study for the aspiring doctor or apothecary. Familiarity with plants and garden design became therefore one of the accomplishments expected of the educated. By implication therefore, a place of education should have gardens; well-ordered by the dictates of art and the insights of science.

The Botanic Garden

In 1772 St John’s employed Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown (1716–1783), doyen of English landscape designers, to revamp their Fellows’ Garden. In 1779 he presented a master-plan for reordering the Backs as a single unified parkland, sweeping away existing avenues of trees and – more importantly – overriding boundaries between different college properties. This proved several steps too far. Thanked politely for his efforts with a silver presentation plate, he was sent on his way.

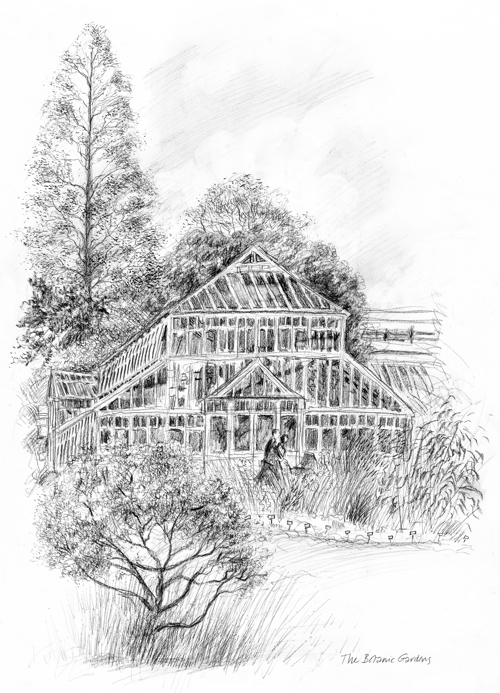

The Botanic Garden

Oxford, although no great friend to science, had acquired a Botanic Garden for teaching purposes by the 1620s, belatedly following the Continental examples of Pisa, Padua and Heidelberg. Cambridge had to wait more than another century to do so. William Heberden (1710–1801) of St John’s in April and May 1747 gave a course of 31 lectures – with a week’s break for the Newmarket races – on the medicinal uses of local plants. Alas for Cambridge, Heberden soon afterwards qualified as a member of the Royal College of Physicians and left for profitable private practice in the capital – ‘much lamenting the want of a Public Garden.’ This loss rankled with the Master of Trinity, Richard Walker (1679–1764), who had his own personal patch of ‘exotics’ like pineapples, bananas and coffee. A passionate ‘florist’, he was astonished when a fellow enthusiast shot himself dead one spring, bursting out ‘Good God! Is it possible? Now, at the beginning of tulip time!’ In 1760 Walker at his own initiative and expense bought land for a university Botanic Garden (on the future site of the Cavendish Laboratory), conveying it in trust to the university.

The expansion of the town in the early 19th century made it essential to remove Walker’s bequest to a more spacious location. This was achieved by the Rev John Stevens Henslow (1791–1861), professor of Botany and mentor of Darwin. Henslow was also curate at St Mary the Less, whose churchyard is now an explorer’s delight for children. The Botanic Garden finished moving to its new 20-acre (since expanded to 40-acre) site in 1846. Henslow’s other major contribution was to extend the Garden’s purposes beyond a purely medicinal remit so that plants might be collected and studied for their economic potential. He is memorialised in the name of Henslow’s Walk.

Originally open to all ‘respectably dressed strangers’, the Botanic Garden was a much-favoured refuge of former Pink Floyd star Syd Barrett (1946–2006) after he had renounced rock ‘n’ roll for abstract painting. Major features now include rock gardens of limestone and sandstone, a Scented Garden, Dry Garden and Winter Garden, more than 20 specimens of trees of record dimensions and nine national collections, including those of geraniums, fritillaries and tulips. The Garden now modestly describes itself as ‘particularly good in July-August; particularly interesting in winter’. It is also still home to the Faculty of Plant Sciences. Its architectural features include the iron gates of its predecessor on Free School Lane and a Director’s House (1924) by Mackay Hugh Baillie Scott, rhapsodically described by Pevsner as ‘a rare example of what perfection the neo-Georgian or neo-Colonial style could attain.’ In 2011 the Sainsbury Laboratory was opened for 120 researchers in the Department of Plant Sciences, also providing a new home for the University Herbarium, which houses 1,000,000 plant specimens, including those collected by Darwin during his voyage on HMS Beagle.

College Gardens

The college gardens at Sidney Sussex date from the 18th century. University historian George Dyer, writing in 1814, was effusive in his praise – ‘an admirable bowling-green, a beautiful summer-house, at the back of which is a walk, agreeably winding, with a variety of shrubs intertwining and forming … a fine canopy … with nothing but singing and fragrance and seclusion: a delightful summer retreat; the sweetest lover’s or poet’s walk, perhaps, in the University.’ The main lawn is now split by a bank, a surviving vestige of that ancient defensive moat, the King’s Ditch, and dominated by a beech and a horse chestnut tree, both huge. Herbaceous borders are hemmed in with low box hedging. Beyond an arch in a high yew hedge lies an unexpected hidden garden of lawns and shrubs. A small rock garden is easily missed. The flowers of a formidable wisteria overhang the garden wall at the junction of Green Street and Sidney Street.

George Dyer was more measured about the gardens at Jesus – ‘though they contain but little of shrubbery, they are, at least, the best fruit gardens in the university … in the fellows’ garden is a good proportion of flowers and plants, which, to assist the botanical student, are marked with their scientific names, according to the system of Linnaeus.’

At Emmanuel a surprisingly spacious garden features an ornamental pond once stocked with fish when the Dominican friary stood here. Now ducks hold sway and even have their own page on the college website. Wendy Taylor’s statue ‘A Jester’ marks the site of a 16th century tennis court. The majestic Oriental plane tree is more than two centuries old, grown from seeds gathered at Thermopylae of ancient fame. In the 1960s a Tudor-style knot-garden was created in New Court.

Pembroke’s tranquil garden features rich herbaceous borders. Arthur Benson spoke of it as ‘a beautiful, embowered, bird-haunted place’. The elegant oasis of Peterhouse is similarly tucked away behind the Fitzwilliam Museum. From the 1860s until the interwar years the area contained a deer park, whose inhabitants periodically provisioned the dons’ table.

Henry James thought Trinity Hall’s riverside retreat was ‘the prettiest corner of the world … narrow and crooked; it leans upon the river, from which a low parapet, all muffled in ivy, divides it; it has an ancient wall adorned with a thousand matted creepers on one side, and on the other a group of extraordinary horse-chestnuts. The trees are of prodigious size; they occupy half the garden’. The don showing him round agreed that it was ‘the most beautiful small garden in Europe.’

The Fellows’ Garden at Christ’s College is famous for a mulberry tree traditionally associated with Milton and held to be the survivor of 1,000 Cambridge mulberries planted at the behest of James I as part of an ill-managed attempt to establish a native British silk industry. Unfortunately the King’s mulberries were the kind silk-worms don’t eat – Morus nigra, not Morus alba. (Jesus also has a sole survivor of this initiative, though there are none at Emmanuel, which also pandered to the royal whim.) The cypress trees at Christ’s were raised from seeds gathered around the tomb of Shelley in Rome. (Unlike Milton, Shelley has no direct connection to Cambridge but went to University College, Oxford until they threw him out.) The nearby 18th-century plunge pool at Christ’s is now more picturesque than inviting, perhaps because the water is third-hand, having come underground from Emmanuel, which takes it from the Botanic Garden. Christ’s also has a memorial to C P Snow, of ‘Two Cultures’ fame.

The Fellows’ Garden at Magdalene College includes a Victorian pets’ cemetery. When Rudyard Kipling was made an Honorary Fellow in 1932 he wrote to his daughter that, apart from having free use of a Guest Room, ‘my other privilege is to walk on the grass of the Quads and in the Fellows’ Garden. Undergrads are crucified for doing this.’ Kipling’s poetic licence may be granted, but the 1958 edition of the Blue Guide made a similar point with equal succinctness – ‘Cambridge lawns are sacred to the feet of resident Fellows.’

The poet A E Housman once wrote:

Loveliest of trees, the cherry now,

Is hung with bloom along the bough

And stands about its woodland ride

Wearing white for Eastertide.

Housman, an assiduous member of the Trinity College gardening committee, is appropriately commemorated by an avenue of cherries planted along the Backs.

Selwyn College gardens reflect the High Victorian delight in huge flowerbeds, a reaction against the ‘natural’ look of the previous century with its emphasis on trees and shrubs. Appropriately, the planting of one bed celebrates the college connection with New Zealand, for whose first bishop the college is named.

The Newnham College website, apparently without intending a pun, describes the development of its gardens as ‘organic’, by which it means that a plan devised by the eminent Gertrude Jekyll was not adopted, except for the notion of extensive herbaceous borders. The oak opposite Clough Hall was a gift from Prime Minister Gladstone (1809–1898). Newnham’s first principal, Anne Jemima Clough, promoted gardening to expose young ladies to fresh air and exercise – as well as valuing it as a provider of wholesome food. Clough’s successor, ‘Nora’ Sidgwick was memorialised with a summer house in 1914. Unusually among Cambridge colleges no grassed area of Newnham 17 acres is out of bounds to undergraduates.

During both World Wars Cambridge college gardens were sacrificed to grow food rather than flowers. Blessed with 46 acres of grounds and conveniently near ample supplies of manure from the university farm, Girton set a praiseworthy example under Chrystabel Procter (1894–1982), then one of the few female head-gardeners in Cambridge. The Fellows’ Garden at Girton was created by one of its graduates, a doyenne of modern English gardeners, Penelope Hobhouse.

New gardens

Intriguingly for a university which habitually thinks in centuries, several of the most outstanding college gardens are essentially post-war creations. The Fellows’ Garden at Clare, arguably the most consistently admired in Cambridge, was recreated by a college fellow, biologist Professor Nevill Willmer (1902–2001), whose landscape ‘pictures’ reflect his passions for plants, painting and optical science. Willmer’s celebrated herbaceous borders demonstrate his theories about how human perceptions of colour change with changing light, blues becoming lighter at dusk, as yellows simultaneously deepen. The planting of white flowers only along the walk between Garret Hostel Lane and the old kitchen garden wall exaggerates its perceived length. A curving lawn running down to the Cam provides a perfect setting for garden parties and balls, and a sunken water garden makes an equally suitable backdrop for outdoor theatricals in summer. The lily pool enclosed on three sides by a clipped yew hedge was inspired by a garden at Pompeii. In front of Memorial Court stands a DNA double helix symbol, commemorating James Watson’s link with the college. Fortunately for non-members, the gardens at Clare are among the most accessible, open daily from Easter until September.

The 13 acres of grounds at Robinson College skilfully stitch together ten former gardens of surrounding Victorian and Edwardian properties, absorbed into the college fabric. Mature trees and an ornamental lake with a wooden bridge and elevated walkway are complemented by a croquet lawn, a purpose-built outdoor theatre and an outdoor teaching area. Shrubs, borders and waterways welcome pheasants, woodpeckers, kingfishers, grass snakes and fresh water mussels. Nicholas Chrimes interprets this creation as a nod to William Kent and Capability Brown, the fathers of English-style landscape gardening in which ‘nature was both humoured and tweaked.’

Lucy Cavendish College features an Anglo-Saxon herb garden created in the 1980s by Lady Jane Renfrew, whose special field of archaeology was palaeoethnobotany and who sourced her selection from a tenth-century work by the Benedictine monk Aelfric. Woads and pimpernels and other plants from before the Norman Conquest flourish there, showing how the first English made medicines, perfumes and dyes and flavoured food.

At Murray Edwards College head gardener Jo Cobb has rejected the generally favoured ‘country house’ look in favour of ‘non-traditional’ planting schemes. The gardens are, however, geared to the university’s very traditional calendar. Newcomers are welcomed at the beginning of the academic year in October by a blaze of bright colours, and graduates can expect their great day, 30 June – graduation day – to coincide, not at all by chance, with a peak of floral glory.