6

Reform one: Town

The Municipal Corporations Act of 1835 removed corrupt, self-recruiting oligarchies throughout the country and enlarged the electorate for the selection of their replacements. In Cambridge this strengthened Town against Gown, but even more important in this respect was the Cambridge Award Act of 1856, containing many concessions from a university increasingly preoccupied with its own need for internal reform. Oaths requiring the Town Council to uphold the privileges of the university were abolished; the Chancellor’s Court lost its power to judge university members guilty of misbehaviour; the Vice-Chancellor’s powers to license ale houses, regulate markets and fairs and inspect weights and measures were transferred to Justices of the Peace. Most university and college properties became liable for rates, the main source of local government revenue.

In 1850 the Cambridge Chronicle revealed that Falcon Yard, off Petty Cury, was home to 300 people, sharing just two privies; but while the town was still disfigured by poverty, pollution and prostitution, there is evidence of rising living standards in the opening of two stores which became Cambridge institutions – Robert Sayle’s in 1840 and Joshua Taylor’s in 1861. In 1842 new Assize Courts were built on Castle Hill. In 1849 a major fire destroyed many properties in the market area, necessitating much rebuilding; not until 1875, however, was a regular, professional fire brigade established. Cambridge also became one of the earliest towns in England to open a public library; the dome-lit premises in Wheeler Street served as the Tourist Information Centre until recently and are now occupied by a smart restaurant. The beginnings of a modern public water supply were finally laid on in 1853–55. In 1858 the Cambridge College of Art was opened by the art historian and social critic John Ruskin (1819–1900); it would eventually evolve into Anglia Ruskin University. In 1869 a group of cobblers banded together to establish the first Cambridge Co-operative Society to sell cheap, unadulterated provisions to the humbler members of the community.

Thwarted ambition

My father will probably have informed you how little I was at first captivated by the external appearance of Cambridge … a dull and shabby town … The river Cam both in colour and width strongly resembles a ditch.

Thus, the unprepossessing first impressions of Alexander Chisholm Gooden (1817–1840), son of a wealthy and cultured London businessman, upon arriving at Trinity in 1836. Lodged in Jesus Lane, five minutes from his college, which he immediately pronounced most inconvenient, Gooden soon fell thrall to accepted routine – chapel at 7:00am and lectures at 9:00, with dinner at 4:00 as a brief break, if not a decorous occasion – ‘a savage piece of business; every man mangles the joints for himself … this meal takes not more than twenty minutes.’ Apart from that, as Gooden confided to a former school friend, ‘Hall, chapel, walk in alternate monotony … are the literature, philosophy and science of a Cambridge continuation, I do not call it life’.

Gooden found the town ‘enlivened by very few amusements’, a visit by Wombwell’s celebrated menagerie being one rare high spot and the lodging of circuit judges with their colourful attendants another. The laying of the foundation stone of the Fitzwilliam Museum was a ‘very dull affair’, accompanied by a Latin speech ‘not of Augustan purity’. When Gooden later moved into college rooms his ‘continuation’ would be ‘enlivened’ by the ravings of a neighbouring don drinking himself into dementia.

The freshman’s dutiful letters home reveal a constant preoccupation with colds and constipation. The famously penetrating frosts of Cambridge meant that one night ‘every liquid whatever in my bedroom was turned to ice’. Winter examinations were taken in the unheated Senate House with participants shivering in greatcoats. Gooden’s letters to his mother are replete with euphemistic references to the laxative properties of rhubarb, morbid fears of damp bedding and effusive gratitude for parcels of warm underwear, referred to coyly as ‘unmentionable articles’. Anxieties about the lower social orders – his landlord, landlady and bedder – inhibited Gooden from accepting further home comforts: ‘Mother’s offer of a ham is tempting but I have no keeping place under my own hands and though my people are decently honest, it would not be fair to tempt their virtue by placing unlimited confidence in them.’ In fact they were entirely upright and caring.

Gooden’s overriding aim was a Trinity Fellowship. This involved much tactical thinking, undertaken with agonised advice from his tutors and father, about which prize and scholarship examinations he should contest. These opportunities for academic virtuosity provoked rivalries both collegiate and personal. St John’s and King’s figure frequently on Gooden’s horizon of academic combat, other colleges meriting scarcely a mention. Competitors were judged by character as well as scholarly competence, Gooden dismissing one as ‘a Sim’ (follower of the evangelical Rev Simeon) and ‘a sloven’ (to many the two were inextricably associated), and expressing the fervent wish that ‘a gentleman in creed and cleanliness may beat him’.

Like many good classicists, Gooden laboured over compulsory mathematics, which embraced astronomy and aspects of physics treated mathematically rather than experimentally, such as optics and dynamics. This involved extensive revision in vacations, lest he forget material painstakingly acquired from paid tutors during term-time. Overshadowing all, however, was the university test that labelled a man for life – ‘a man can take his degree but once and there is nothing afterwards to make up for failure in that examination.’

In the end Gooden achieved the foothills of academic eminence, winning the prestigious Chancellor’s Medal in 1840, gaining a creditable degree, attracting pupils and looking forward to election to a junior fellowship. During a vacation in Germany, however, he so over-exerted himself rowing that he died within days, just 23. Apparently his hypochondria wasn’t so misplaced after all.

Railway revolution

In 1845 the Eastern Counties Railway at last reached Cambridge – just about. As anyone with heavy baggage who has missed the last taxi will know, it’s a long mile from the station to the city centre. The university deplored a form of communication by which undergraduates could reach London, and its limitless temptations, in just over an hour. Just as bad, the railway would also enable ‘day-trippers’ to descend on Cambridge, ruining its accustomed serenity. In 1851 the Vice-Chancellor protested that it would ‘convey foreigners and others to inflict their presence on the university and its day of rest’ and that therefore Sunday excursions were ‘as distasteful to the University Authorities as they must be offensive to Almighty God’. The university therefore extracted extraordinary powers from Parliament regarding railway business. University officers were empowered to quiz railway employees about any person on the station ‘who shall be a member of the University or suspected of being such’. On Sundays the railway was forbidden to pick up or set down passengers at Cambridge or within three miles of it between 10:00am and 5:00pm. This ban remained in force until 1908.

For an altogether more positive approach to this new marvel of human ingenuity one must turn to Ely Cathedral, where a fatal accident on the Norwich line in 1845 prompted the inscription of a 24 line verse – The Spiritual Railway – on the grave of the two victims. The following extract conveys an appealingly up-beat message:

The Line to heaven by Christ was made

With heavenly truth the Rails are laid,

From Earth to Heaven the Line extends,

To Life Eternal where it ends.

Repentance is the Station then

Where Passengers are taken in ….

In First, and Second, and Third Class

Repentance, Faith and Holiness,

You must the way to Glory gain

Or you with Christ will not remain.

Come then, poor Sinners, now’s the time

At any Station on the Line,

If you’ll repent and turn from sin,

The Train will stop and take you in.

In 1863 Cambridge station was rebuilt in its present form with the longest platform in Europe, stretching for almost a quarter of a mile. In 1866 a second London route was opened, terminating at King’s Cross. By 1871 the number of day-trippers had grown large enough to stimulate the publication of a forerunner of this book – A Railway Traveller’s Walk Through Cambridge.

Some limited industrial development took place alongside the railway, notably the premises of James Sendall & Co, Horticultural Builders, Heating Engineers and Iron Founders, whose speciality was glasshouses. In the 1880s and 1890s Romsey Town developed as a working-class suburb of brick terraces, many inhabited by railway workers. In 1894 Fosters opened their giant flourmill by the station. Another minor industrial nucleus developed along the Newmarket Road with quarries, half a dozen brick and tile works, an iron foundry, a gas works and coal yards. The concentration of men doing heavy industrial work created a corresponding demand for places where they could ‘put the sweat back in’. At one time there were no fewer than 22 pubs between Wellington Street and Hutchinson’s Court, one every 22 yards.

Speaking volumes

A significant commercial development occurred in the town centre in 1843 when the corner shop at No 1 Trinity Street was taken over by Daniel Macmillan (1813–1857) and his brother Alexander (1818–1896), who soon branched out from bookselling into publishing. Thackeray and Tennyson both gave readings on the premises. In April 1857 the firm published that enduring classic Tom Brown’s Schooldays, which ran through five editions before the end of the year. Other key Macmillan titles would include Francis Turner Palgrave’s Golden Treasury of English Songs and Lyrics (1861) and Charles Kingsley’s The Water Babies (1863). When the firm moved to London in 1863, the former premises passed to a nephew, Robert Bowes (1835–1919), and the business traded as Macmillan and Bowes until 1907 and then as Bowes and Bowes. Robert Bowes became a civic stalwart, a town councillor and a major in the local Volunteers, governor of the Perse School, promoter of Cambridge Working Men’s College and Newnham College and an expert on John Siberch and the history of printing in Cambridge. He was also responsible for publishing the Concise Guide to Cambridge (1898) by John Willis Clarke and a facsimile edition of Cantabrigia Illustrata.

The Fountain at Trinity College

Polymath

You’ll find, though you traverse the bounds of infinity,

That God’s greatest work is – the Master of Trinity.

Sir Francis Doyle, 1866

William Whewell (1794–1866) – pronounced Hyou-well – was the scientist who invented the word ‘scientist’, and ‘physicist’ as well. He was also a priest, poet, philosopher and translator and wrote authoritatively on subjects ranging from tides to German Gothic churches. Born a carpenter’s son, he died the immensely rich Master of Trinity. A gangling youth, Whewell matured into a prizefighter’s physique and, even in middle age, could jump the entire flight of steps up to Trinity’s Dining Hall in a single bound, a feat generations of undergraduates have tried – and often failed – to emulate. Winner of a university prize for English poetry, Second Wrangler, President of the Union Society, a founder of the Cambridge Philosophical Society and FRS at 26, Whewell spoke German so well he was turned away from meeting Humboldt (1769–1859) because a porter was told to admit only an Englishman. Successively Professor of Mineralogy and Professor of ‘Moral Theology and Casuistical Divinity’, Whewell also served as President of the Geological Society and of the British Association for the Advancement of Science. His magnum opus was a comprehensive account of the history and philosophy of all science. Whewell described science; he was not interested in experiment.

Whewell was contemplating quiet retirement when in 1841 his life was totally transformed by his belated marriage and unexpected election as Master of Trinity. Whewell used this powerful position to secure the election of Prince Albert, husband of the young Queen Victoria, as Chancellor of the University in 1847, aiming, with Albert’s enthusiastic support, to broaden the curriculum by promoting the teaching of philosophy and science. Whewell’s views on what science should be taught to undergraduates were, however, decidedly cautious, not to say reactionary. Mathematics offered certainties, science rather too much speculation. Nothing, therefore, should be allowed on the curriculum which had not been generally accepted among the scientific community for at least a century. Standing outside academia, Prime Minister Sir Robert Peel (1788–1850), who had personally chosen Whewell as Master of Trinity, wondered wryly whether the young gentlemen of Cambridge were to be exposed to such apparently contentious matters as electricity. Reformist, but no radical, Whewell believed that if Cambridge needed reforming, it should be left to reform itself, ferociously defending such traditions as college autonomy and the exclusion of Dissenters.

Outside Cambridge Whewell was known for a tract arguing that the Earth was not unique in the universe as the only populated planet. This view was readily endorsed by that perennial punster the Reverend Sydney Smith (1771–1845) who, being told that Whewell’s strong point was science, riposted that his weak point was ‘omniscience’. Whewell also took as a proof of the existence of God as Designer of the Universe that the daily rotation of the earth provided exactly the time humans needed to sleep.

Whewell made two happy marriages, which, with the incomes from his various offices, made him wealthy enough to pay for the building of two student hostels as well as endowing a chair of international law, to promote perpetual peace between nations. A notoriously poor horseman, Whewell died after a fall, accompanying his nieces in the Gog and Magog hills. He is buried in the ante-chapel at Trinity where there is a statue (1872) by Thomas Woolner (1825–1892). Opposite him is a statue (1845) of one of Whewell’s own heroes, Francis Bacon, which Whewell had himself set up. The fourth line on the front describes Bacon as Scientiarum Lumen Facundiae Lex (Light of Knowledge and the Law of Eloquence) while the fifth refers to his slumped posture Sic Sedebat (he used to sit like this) when cogitating deeply. On the side of his chair is an extract from a letter Bacon wrote to Trinity, urging the study of science as evidence of God’s Creation. Whewell can also be seen in effigy on the outside of Whewell’s Court, looking down on the former All Saints churchyard.

In contrast to the flamboyant Whewell, Isaac Todhunter (1820–1884) was the archetypal ascetic recluse. Asked how long a ‘hard reading man’ could take off, he advised that ‘the forenoon of Christmas Day would be in order’. Despite having been ‘unusually backward’ at school, he became a teacher himself through evening classes at University College, London. Entering St John’s at an elderly 24, he devoted 15 years to monastic frugality and highly profitable industriousness. Using his college lodging as an austere classroom, he inhabited two closets, one as his bedroom, the other his study, lined with books; ‘each in a brown paper cover inscribed in exquisite handwriting with the title’. Apart from an hour walking college footpaths for exercise and an hour for dinner, Todhunter devoted every waking moment to teaching or compiling mathematical textbooks which became runaway bestsellers. According to his former pupil Leslie Stephen, editor of the Dictionary of National Biography, by 1864 he ‘had saved enough money to give up the drudgery of teaching, married and wrote books for the learned upon the history of mathematics’. Todhunter also mastered nine languages.

Reform two: Gown

The reforms initiated by the Duke of Newcastle in 1750 fended off further change at Cambridge for a century. He was succeeded in 1768 by the Duke of Grafton (1735–1811), who made no official visit after 1774 – i.e. for almost 40 years. On his election his successor, William Frederick, Duke of Gloucester (1776–1834) – one of several royal personages to be thought the original ‘Silly Billy’ – gave a celebratory dinner so lavish that guests were seated in Trinity’s cloisters. After that he visited just twice. At 75, his successor, the Marquis of Camden (1759–1840) was an unlikely candidate for firebrand reform and fended off threats of external interference with promises that the colleges were diligently beavering away at their own proposals for improvement. His successor, the Duke of Northumberland (1785–1847), maintained this semi-fiction and probably felt he’d done his bit by donating in 1842 the immense Warwick Vase that stands on the Senate House lawn.

The election of Prince Albert in 1847 therefore marked something of a break with a tradition of torpor and obfuscation. Not yet 30, Albert was itching to be useful and, as a German and a fully paid-up intellectual, was painfully aware how far the ancient English universities languished behind their continental counterparts – or even their newer rivals in London and Durham.

Some of the colleges had begun tentative reforms. Trinity had introduced an entrance examination. Peterhouse had no longer limited fellowships to men from particular counties. Theologian Dr John Graham (1794–1865), Master of Christ’s and a close ally of Prince Albert, even suggested fellows might marry and the university be opened to non-Anglicans.

In the event the ancient universities were unable to fend off the appointment in 1852 of a Royal Commission, whose brief was ‘to enquire into the state, discipline and revenues’ of the university and its colleges. They interpreted this very broadly to recommend the establishment of courses in engineering, modern languages, history and theology, to suggest the establishment of Boards of Studies to ensure what was taught matched what was examined and to establish new professorships and lectureships open to married men, plus the creation of new laboratories and museums. The commissioners did not, however, propose anything as radical as a general entrance examination and made only anodyne proposals in relation to the colleges. In the end Caius took the lead in abolishing celibacy, though other colleges followed only hesitantly over the following 20 years.

The university predictably tried to pre-empt external reform by making its own proposals but, equally predictably, failed to finalise them in time. Accordingly, in 1856 the Bill for Cambridge was passed by Parliament to revise the complex structure of governance of the university, abolish obsolete offices, redirect ancient endowments to fund new professorships, lengthen terms and tighten up residence requirements. Henceforth a declaration of faith was only required of those taking degrees in divinity, although fellowships and membership of the senate were still limited to Anglicans. Religious restrictions were finally lifted from 1871 onwards, although it was decreed that Morning and Evening Prayer should still be observed in college chapels. Subsequent Royal Commissions recommended raising standards in Scientific Instruction (1873) and decreed that college contributions be required to support university teaching (1877), a move which was denounced as an assault on the autonomy of colleges – which it was.

Revival: Gothic

While Downing College and the Fitzwilliam Museum were large-scale exercises in the neo-Classical mode, interest in the newly-fashionable Gothic mode of architecture was quickened by the drastic but highly praised restoration of Holy Sepulchre church undertaken by Anthony Salvin (1799–1881) as a consolation prize for not getting the commission for the Fitzwilliam. A protégé of John Nash, Salvin was Britain’s leading authority on medieval castles. At Cambridge his first college project in 1852 was to remodel the east range of the Principal Court at Trinity Hall in a restrained Italianate manner. In 1853 he undertook a complex remodelling of the hall and library on the west side of Caius. Salvin had by then found favour with Whewell of Trinity, for whom he had restored the façade of the Master’s Lodge (1843) and then built Whewell’s Court (1859–60, 1866–8), commended by Pevsner as

… amongst the most satisfying of nineteenth century Cambridge buildings … The best thing … is the sensitive scaling of the three parts … The first court … small, irregular in shape and paved … the second no more than a strip of turf … Yet … visually … an extremely pleasant interlude. The other main court … much larger and squarer, with a turfed centre and two big square towers as its main accents …

Salvin was also responsible for the east window at St Mary the Great in 1857. All Saints, Jesus Lane (1864), the work of G F Bodley (1827–1907), brother-in-law and first pupil of Sir George Gilbert Scott (1811–1878), replaced the demolished All Saints in St John Street, traditionally known as All Saints in the Jewry or All Saints by the Hospital. Its former churchyard now features a memorial cross designed by Basil Champneys. Bodley’s All Saints (now closed) features decorative work, notably the famed east window, by William Morris and his usual collaborators Ford Madox Brown and Edward Burne-Jones. Their collaboration began in 1861 with restoration work on the hall at Queens’, one of the very earliest of Morris’s projects, and there was a similar collaboration on the 1864–7 restoration of the chapel at Jesus College and the installation there in 1873–7 of new stained-glass windows. Bodley’s work at Cambridge continued over more than 40 years, beginning in 1858–61 with the redecoration of the chapel at Queens’. In 1885 he redecorated Holy Trinity, Market Street, the former stronghold of Charles Simeon. Bodley’s Buildings (1893) at King’s is a bold, L-shaped neo-Tudor block, while Christ’s library (1895–7) is a discreetly tactful addition.

Sir George Gilbert Scott built up the largest architectural practice in Victorian England and is credited with some 700 projects. Pevsner scathingly characterises Scott’s Chapel of 1863–9 at St John’s College as ‘eminently High Victorian in that it is oversized, correct in its details and utterly unaware of what the unity of a court demands’. 193 feet long, with a tower 163 feet high, its late-13th century Gothic is supposed to represent what Scott thought the original college chapel would have looked like, modified by nods towards the chapel of Merton College, Oxford and the Saint-Chapelle in Paris. Scott also (1862–5) enlarged the Hall at St John’s. His other Cambridge work included the rebuilding (1862–7) of most of the West Court of the Old Schools, the 1867 restoration of medieval St Mary Magdalene and the design of the Chetwynd Building (1873) at King’s College. He also made major alterations at Ely Cathedral – moving the choir stalls, inserting a choir screen and reconstructing the famous lantern.

Scott’s successor as doyen of the profession was Alfred Waterhouse, RA (1830–1905), best known as the architect of the Natural History Museum in London. Having established a solid reputation in Manchester and Liverpool, Waterhouse approached Cambridge with even more self-confidence than Scott. The Union building of 1866 was at least tucked away, but his 1868–70 rebuilding of Tree Court at the south-east corner of Caius could scarcely have been more prominent. Pevsner is incandescent about its external frontage:

at the corner the building blossoms out into a tall tower … a spire, big chimneystacks, a monumental gateway … statuary in niches, in fact everything the architect could think of … The tower … dwarfs the Senate House … competes with St Mary and … is pretentious and … utterly unconscious of the character of the architecture into which it should fit …

The work was, however, hailed as an outstanding success when completed and in 1883 the architect returned to Caius to build a set of Lecture Rooms.

In the meantime, Waterhouse had made a Tudor undergraduate block at Jesus, a new Master’s Lodge, Hall, Library and accommodation block at Pembroke (1871–5) and the east range of New Court at Trinity Hall (1872). Noting that Waterhouse was ‘the last architect to be guided by respect for the character of old work’, Pevsner observes of his efforts at Pembroke that ‘in every case where he added … he spoiled something that was there and replaced it by something out of keeping’. Pevsner does, however, warmly commend the eclectic New Building (1878) added by Gilbert George Scott Junior (1839–1897), with its mixture of Gibbsian window-surrounds, Arts & Crafts angels and Dutch gables.

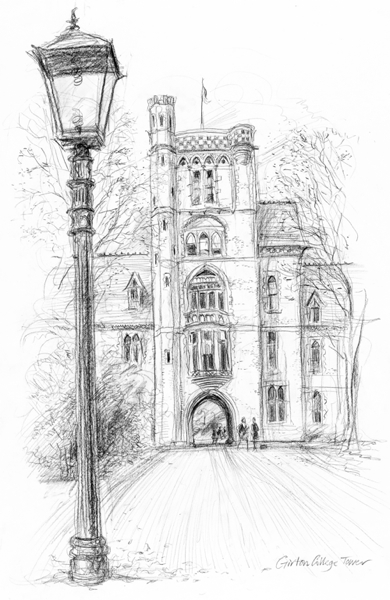

Waterhouse rounded off his Cambridge collegiate oeuvre at Girton, employing his favourite materials of red brick and red terra cotta. The first building, for the Mistress, one lecturer and 21 students was completed in 1873 and now forms part of Emily Davies Court. Far more important, however, was Waterhouse’s major innovation in student accommodation, substituting corridors for staircases to link student rooms. This not only introduced much more light and air but also minimised social isolation and maximised social interaction and rapidly became the norm. Waterhouse continued to make additions in the same style at Girton before handing work over to his son, Paul (1861–1924), followed by his son, Michael (1888–1968).

Girton College Tower

Alfred and Paul Waterhouse were jointly responsible for Fosters’ (now Lloyd’s) Bank (1891) on Sidney Street. Striped bands of limestone and brick emphatically mark the building off from nearby colleges as being unmistakably ‘town’ not ‘gown’. The bank’s Dutch-style gables and tower assert a brash, bourgeois self-confidence, which implied that any cash left in the care of the Fosters – local millers-turned-bankers, who also supplied four Cambridge Mayors – could not be more secure. Exuberance, however, was reserved for the stunning tiled interior. Do pop in for an exhilarating glance.

No 10 Trinity Street was built in the 1880s for a firm of solicitors, which included two members of the Foster family, one of them a Cambridge Town Clerk. The Gothic pediment above the doorway is an hourglass (a warning to clients not to waste time?) surrounded by finger-wagging advice – Praeteritum Corrige (Correct the Past) Praesens Rege (Control the Present) Futurum Cerne (Perceive the future). Decades of 20th-century undergraduates knew this building as The Whim, which, when Clive James was a postgraduate in the 1960s, served the self-defined ‘artistic world … as a headquarters, clearing house, comfort station, watering hole and gossip exchange. The Whim worked on the French café system: you could sit for a long time over a single cup of coffee as long as you didn’t mind paying too much for it in the first place. I enjoyed writing there because there was a good chance of being interrupted.’

‘this very unrevolutionary woman’

Girton College was essentially the creation of (Sarah) Emily Davies (1830–1921). Denied education by her clergyman father, following his death at 30 she threw herself into campaigning for women’s rights to employment, education, medical training and the vote. Small and plain, Miss Davies proved a first-rate organiser and public speaker. In 1867 she began to plan the establishment of a woman’s college offering education at university level. It opened in 1869 with five students in temporary accommodation at Benslow House, Hitchin, Hertfordshire, 30 miles from Cambridge. In 1873, the college, by now with 15 students, relocated to an extensive 46 acre site near Girton, two miles from the male-dominated centre of Cambridge. Emily Davies had enlisted capable and influential supporters to her cause, not least the eminent novelist George Eliot (1819–1880), but Girton nevertheless represented the triumph of her own unspectacular combination of tact and tenacity. (Her tact was, however, sometimes selective – ‘Girton is for ladies, while Newnham is for governesses’.) The university’s official history is unusually fulsome in its praise – ‘one of the heroic figures in Cambridge history; firm as a rock, endlessly fertile in plans and schemes, ruthlessly persuasive, all at once friendly and formidable’ but also admits that ‘she had little conception of scholarship; she never knew much of Cambridge – she escaped to London whenever she could.’

Eschewing any form of pedagogic apartheid, the first Mistress of Girton aimed to have her students perform at the same level as the men and, as far as possible, under the same conditions. She was triumphantly vindicated in 1887 when Agnata Ramsay (1867–1931) was awarded higher marks than the officially-recognised Senior Classic. Henry Montagu Butler (1833–1918), Master of Trinity, promptly married Miss Ramsay (34 years his junior) – certainly some sort of recognition; but it would be another 60 years before Cambridge women were actually entitled to a degree for their examination performance. Agnata’s marriage proved happy and fruitful. The eldest of her three sons, James Ramsay Montagu Butler (1889–1975) became Regius Professor of History.

Miss Davies’ other main aim was to build accommodation and teaching facilities for hundreds of future students. A chapel, library and garden could wait. In fact they were realised long before her demise, which was nice but not, in her view, the point. As the university’s official history notes ‘she left Girton loaded with debt, but very amply provided with buildings’.

On the Cam

Harvard graduate William Everett (1839–1910) read classics at Trinity between 1859 and 1863 before returning home to an unspectacular academic career. He did, however, produce what the distinguished American historian Henry Steele Commager hailed as the best American account of Cambridge life, On the Cam (1866). Everett argued that both England’s ancient universities were essentially aristocratic institutions – ‘not means for diffusing education among the people, but … the great training schools for the governing classes.’ But he drew a fundamental distinction between the two. Whereas Oxford was chiefly patronised by the ‘old aristocracy’ of hereditary landed wealth, Cambridge attracted the offspring of the ‘new aristocracy’ of business and the professions – ‘the wing devoted to progress and the new world of thought is devoted to Cambridge’. Certainly in the promotion of science Cambridge would increasingly set the pace.

The first guidebook to Cambridge, Cantabrigia Depicta (1763), rhapsodised over the excellence of the ‘Flesh, Fish, Wild-Fowl, Poultry, Butter, Cheese and all Manner of Provisions from the adjacent country’. Butter, in particular, was singled out for its abundance and the peculiar way it was sold, which fascinated the novelist Maria Edgeworth (1767–1849) in 1813 – ‘All the butter in Cambridge must be stretched into rolls a yard in length and an inch in diameter, and these are sold by inches, and measured out by compasses, in a truly mathematical manner, worthy of a university’. ‘Yard Butter’ survived until the rationing regulations of the Great War killed it off. The other local speciality was ‘the best Saffron in Europe’.

Short commons

These observations were written after the draining of the Fens had opened up an immense new region of highly productive soil and when East Anglia was at the forefront of an ‘agricultural revolution’ which was transforming breeds, crops and techniques of cultivation. Two centuries previously a future Master of St John’s, preaching at Paul’s Cross in London, had envisaged the average Cambridge scholar living a life of extreme frugality. Rising between 4:00 and 5:00, he should dine at 10:00am, sharing ‘a penny piece of beef amongst four, having a … porridge made of the broth of the same beef, with salt and oatmeal, and nothing else’. Supper, at 5:00pm, was to be ‘not much better than their dinner’. The austere Bishop Fisher commended keeping students half-starved, a ‘low diet’ being ‘necessary to concentration.’ The confessional diary of undergraduate Samuel Ward in 1595–6 shows him failing to live in Puritanical self-denial – bingeing variously on cheese, pears, walnuts, raisins and damsons and ‘going to drink wine and that in the Tavern’. Writing in March 1625, Lady Paston kept her son William, at Corpus Christi, supplied with home-made treats, which she repeatedly urged him to share: ‘I have sent thee, as thou desirest, some edible Commodity for this Lent to eat in your chamber, your good tutor and you together: a Cake and Cheese, a few puddings and links [sausages]: a turkey pie pasty: a pot of Quinces and some marmalade.’

Outbreaks of plague could disrupt local food supplies so badly that colleges would be reduced to a state of nutritional siege. In 1625 college steward Joseph Mede recorded distractedly that ‘all our market today could not supply us commons for night’, so he had to serve ‘eggs, apple-pies and custards, for want of other fare’. The plague of 1630 caused most of his colleagues and students to flee while the rest remained gated inside, relying on their regular ‘Butcher, Baker and Chandler’ to ‘bring the provisions to the college gates, where the Steward and Cook receive them’. Communal dining was not to everyone’s taste, anyway. The high-handed Master of Pembroke, Samuel Harsnett (1561–1631), thought his status as a bishop entitled him ‘to keep state at his meals in his lodgings’ and to make ‘both the Cooks at once his men … so that sometimes the kitchen was without a cook the whole day together … leaving the College but one poor sole boy to dress commons.’

Writing in 1662, John Strype (1643–1737), a Jesus freshman, reassured his mother that his college was better than most in the matter of ‘Commons’, the daily fare consumed communally in hall, but, even so, it sounded rather dreary:

… we have … such meat as you know I do not use to care for; and that is Veal, but now I have learnt to eat it. Sometimes … we have boiled meat, with pottage; and beef and mutton, which I am glad of: except Fridays and Saturdays, and sometimes Wednesdays; which days we have Fish at dinner, and tansy or puddings for supper.

The custom of ‘fish days’, a hangover from Catholic practice, was regarded as patriotic; maintaining a large fishing fleet created a ‘nursery of seamen’ as a reserve for war. If a meal left one hungry one could buy extra snacks of basics such as bread, butter, cheese or beer, or more self-indulgently, slices of tongue or cake. Veal remained in favour at Jesus for centuries as Coleridge remembered a waiter presenting cuts from a large, coarse animal, ‘tottering on the edge of beef!’

Thomas Gray, newly-arrived in 1737, wrote, in much the same terms as Strype:

if any body don’t like their Commons, they send down into the Kitchen to know, what’s for Sizing: the Cook sends up a Catalogue of what there is; and they choose what they please: they are obliged to pay for Commons, whether they eat it or no: there is always Plenty enough: the Sizers feast upon the leavings of the rest.

In some colleges sizars ate leavings from the fellows’ table – a far more delectable perquisite.

The fastidious Conrad von Uffenbach, visiting in 1710, was less impressed by Trinity’s dining hall than repelled by its ambience – ‘Very large, but ugly, smoky and smelling so strongly of bread and meat that it would be impossible for me to eat a morsel in it.’ He also thought Cambridge inns ‘very ill-appointed and expensive’ and complained that ‘one must dine every day pretty near alike, as on mutton etc.’ Culinary relief came from the celebrated Dr Bentley of Trinity, where Uffenbach was ‘very sumptuously entertained’, though ‘as his wife dined with us, we did not converse upon serious matters.’ Coffee houses supplied another welcome refuge, offering refreshments, the solace of tobacco and the opportunity to read the – then very expensive – newspapers. The Greek’s Coffee House was run by a genuine Greek, whose nationality was thought sufficient to guarantee a mastery of preparing the mysterious brew.

A century later, as a nervous Trinity freshman, future novelist Edward Bulwer-Lytton (1803–1873) learnt the hard way that dining in common had a Darwinian edge to it:

When the dishes were all placed on the table, there was … a murmur and a sudden rush … I dropped into place by an enormous sirloin of beef. This was abruptly seized and a fork stuck in it. A pile then suddenly rose on the plate of my opposite neighbour. Scarcely had he relinquished the sirloin than it was pounced upon by another … A third succeeded and I began to cast a disconsolate glance at a hacked and maimed shoulder of mutton … when I found the beef before me … and was just going to make up for lost time … it vanished in a trice.

Something to celebrate

Major events in the life of colleges – the anniversary of its foundation, the inauguration of a new Master, the completion of a major building project – have for centuries been marked by feasts of splendour, not to say excess. University, as well as college, occasions were traditionally marked by consumption on a heroic scale. As late as the 1820s the formal proclamation of Stourbridge Fair involved rituals of eating and drinking spread over most of a day. At 11:00am the Vice-Chancellor, attended by an entourage of university officers, went to the Senate House ‘where a plentiful supply of mulled wine and sherry … with a great variety of cakes, awaited their arrival’. Having despatched these, the official party proceeded by carriage to the Fair itself, where, after making the formal proclamation, they were ‘joined by numbers of Masters of Arts, who had formed no part of the procession, but who had come for the express purpose of eating oysters. This was a very serious part of the day’s proceedings and occupied a long time.’ After a brief interval, during which waiters reordered the dining area, a dinner was served, for some 30 to 40 persons, consisting of an unvarying annual menu of herrings, roast neck of pork, ‘an enormous plum pudding’, legs of pork boiled, pease-pudding, goose, apple pies and ‘a round of beef in the centre’. The wine, apparently, was ‘execrable’ but a great deal was drunk before the party broke up at 6:30pm.

To mark Queen Victoria’s coronation in June 1838, the people of Cambridge had a huge picnic on Parker’s Piece, attended by 3,000 Sunday school pupils and ‘charity children’ and 12,000 of ‘the poor’. £1,758 collected from the city’s affluent residents paid for 7,029 joints of meat, 4,500 loaves of bread, 1,650 plum puddings and 99 barrels of beer.

The more affluent mid-Victorian undergraduates entertained each other to substantial breakfasts between nine and ten. Coffee, tea and muffins were bought in from ‘town’ while the college kitchen supplied hot dishes such as soles, cutlets, steaks, chops or ‘spread eagle’ – a fowl split and stewed with mushrooms. This was followed by the smoking of pipes and the consumption of ale or cider before the party dispersed to aid their digestion by sitting through a lecture or two before lunch.

As the cult of sport came to dominate the late Victorian university the proliferation of sporting clubs provided occasions for lavish formal dinners – at least formal when the evening began. The menu for the University Drag and Beagle Hunt in 1892 consisted of solid stuff to fill solid young men – Mock Turtle or Clear Spring Soup, Salmon with Cardinal Sauce or Smelts with Hollandaise Sauce, Sirloin of Beef or Saddle of Mutton, followed by Braised Fowl a la Milanaise or York Ham and topped off with Winchester Puddings, Rhubarb Tarts and Jellies. The Bump Supper served at Caius a couple of years later was even more pretentious, the Frenchified menu studded with in-jokes based on the local landscape – ‘Potage a la get-out-at-the-Pike-and-Eel’ and ‘Canard Sauvage a la Ditton Fen’ etc.

Victorian dons indulged in domestic dinner-parties, gargantuan by modern standards, throwing a huge burden on their servants. Lady Caroline Jebb (1840–1930), an American by birth, knew she had a gem in her Mrs Bird who, with only the help of a girl hired for the day, single-handedly prepared for a dozen guests fresh-baked rolls, ‘white soup’, sole fillets with lobster sauce, roast leg of mutton, turkey with oyster sauce and roast duck with its sauce. Two entrées – foie gras and ‘sweetbreads stewed with mushrooms and truffles’ – were sent over from the college kitchen to give Mrs Bird breathing-space between courses. College also supplied a plum pudding and a Charlotte russe, followed by cheese and ‘desserts’.

Gwen Raverat (1885–1957), the celebrated wood engraver, remembered the social perils of such occasions:

The guests were seated according to the Protocol, the Heads of Houses ranking by the dates of the foundations of their colleges, except that the Vice-Chancellor would come first of all. After the Masters came the Regius Professors in the order of their subjects, Divinity first; and then the other Professors according to the date of the foundations of their chairs … It was better not to invite too many important people at the same time or the complications became insoluble to hosts of only ordinary culture. How could they tell if Hebrew or Greek took precedence, of two professorships founded in the same year?

In April 1885 Raverat’s parents gave a small dinner party, with only two male guests, but the menu still ran to Tomato Soup, Fried Smelts and Butter Sauce, Mushrooms on Toast, Roast Beef, Cauliflower and Potatoes, Apple Charlotte, Toasted Cheese and a dessert selection of Candied Peel, Oranges, Peanuts, Raisins and Ginger. In October of the same year the guest of honour was eminent scientist Sir William Thomson (1824–1907), so the menu was even grander – Clear Soup, Brill and Lobster Sauce, Chicken Cutlets and Rice Balls, Oyster Patties, Mutton with Potatoes, Artichokes and Beets, Partridges and Salad and then a choice of Caramel Pudding or Pears and Whipped Cream, followed by Cheese Ramequins or Cheese Straws, followed by an Ice, concluded with Grapes, Walnuts, Chocolates and Pears – the whole extravaganza prepared and served by three household servants, Gwen’s mother eschewing College staff as an extravagance.

Bachelor dons in the wealthier colleges needed no outside invitations to indulge themselves. Larger-than-life historian, Oscar Browning, a Fellow of King’s for 50 years, began daily with bread and butter and tea in bed, followed by a full breakfast in hall, had lunch, with claret, then afternoon tea and for dinner soup, fish, a joint, hot dessert, cold dessert and savoury, with champagne. He then set his alarm clock for 3:00am to drink a bottle of strong ale. ‘Hard daily tennis and a Turkish bath’ and vacation exertions, like crossing the Alps on a tricycle, helped him live to 86.

After the Great War large-scale domestic dinner parties were curtailed by the rising cost of servants and the falling value of academic salaries. But collegiate bachelors were largely cushioned from these. Mansfield Forbes (1889–1936) of Clare ‘entertained with erratic munificence’, characteristically Sunday breakfast parties for a dozen guests which started at 9:00 and ‘were apt to go on indefinitely.’ For the host the guests mattered more than the food. On one occasion he ‘scoured the country to collect seven red-haired curates as a sort of centrepiece … and on another … a large number … all of whose names ended in –bottom or –botham, and left them to mutual introductions.’

In 1929 A E Housman hosted a dinner for ‘the Family’, an exclusive donnish dining club originating as a semi-secret Jacobite clique. Members included the Masters of Clare, Magdalene and Downing, the Regius Professor of Physic, the Professor of Astrophysics and the University Librarian. Their meal began with Whitstable oysters, with a 1918 Meursault; then came a pastry appetiser with Oloroso sherry, sole fillets with a 1921 Auslese, mutton cutlets, noisette potatoes and buttered green beans, with a 1921 Pommery, followed by a savoury, four desserts, two more wines, port (1878!) and cognac (1869!).

Virginia Woolf, lunching at King’s in the 1920s, ate soles and partridges – ‘many and various … with all their retinues of sauces and salads … potatoes, thin as coins … sprouts, foliated as rosebuds’ and then, ‘wreathed in napkins, a confection which rose all sugar from the waves.’ This was in the most blatant contrast to the austerity described in her depiction of fictional ‘Fernham’ (i.e. Newnham) College where dinner consisted of ‘plain gravy soup … beef with its attendant greens and potatoes … prunes and custard … biscuits and cheese’, with tap water to drink. Noting fair-mindedly that ‘the supply was sufficient and coal-miners doubtless were sitting down to less’, she yet cannot have imagined the gastronomic privations that a second World War would inflict on a future generation of female students, when the young ladies of Girton would consume the college swans, first as roasts, then as rissoles and finally as soup.