9

The terrible hiatus of World War One ensured that the post-war intake of undergraduates was more varied than the customary influx. The writer J B Priestley (1894–1984), wounded twice and commissioned from the ranks, recalled a ‘crowded and turbulent’ Cambridge where ‘men who had lately commanded brigades and battalions’ were mixed up with ‘nice pink lads’. The Caius entry included athlete Harold Abrahams, who had been commissioned, but too late to see action, and a future Master, Joseph Needham, straight out of public school. Kipling realised the veterans deserved special consideration:

Tenderly, Proctor, let them down, if they do not walk as they should;

For, by God, if they owe you half-a-crown, you owe them your four years food.

Others had been flotsam on the tides of war. A ‘White Russian’ exile, the son of a minister in the short-lived Kerensky government, Vladimir Nabokov (1899–1977) inhabited ‘intolerably squalid’ lodgings while at Trinity, ‘trying to become a Russian writer’. Devoting much time to tennis, goalkeeping and punting, he breezed effortlessly through his degree studies in French and Russian literature and found the spare time to translate poems by Rupert Brooke into Russian and to compose a scholarly essay on the butterflies and moths of the Crimea. As he later confessed:

I had no interest whatever in the history of the place and was quite sure that Cambridge was in no way affecting my soul, although actually it was Cambridge that supplied … the very colours and inner rhythms for my very special Russian thoughts.

For Xu Zhimo (1897–1931), a much briefer bird of passage, the impact of Cambridge at that very same time was, by contrast, a self-acknowledged turning-point, both in terms of what he learnt and what he felt. Having studied in the USA, which he found ‘intolerable’, Xu spent much of 1922 at King’s, where the poetry of Keats and Shelley came as a revelation to him. Returning to a troubled China, he flourished as a poet, editor, translator and teacher until he was killed in a plane crash, not yet 35. Xu’s poem, ‘Saying Farewell to Cambridge Again’, drafted on the Backs, became a standard choice for school anthologies, known to millions and therefore ‘arguably the most famous Chinese poem of the twentieth century.’ In July 2008 a two ton block of white Beijing marble was placed as a memorial to the poet at the western end of King’s bridge over the Cam, inscribed in Chinese characters with the first and last two lines of Xu’s subdued lament:

I leave softly, gently

Exactly as I came –

Gently I flick my sleeves,

Not even a wisp of cloud will I bring away.

Right face

Despite the upheavals of revolution in Russia, the accession to power of Fascism in Italy and the advent of the first, if short-lived, Labour government in Britain, the mass of Cambridge undergraduates remained instinctively conservative in outlook, though in a largely apolitical sort of way. During the General Strike of 1926, when the organised labour movement paralysed transport, power and newspapers in support of the miners’ attempts to resist wage cuts, some 2,000 students volunteered to serve as special constables or seized the chance, as unique as it was unexpected, to realise a childhood fantasy by driving a bus or, better still, a train – less as an expression of class hostility than from an eagerness to shirk their studies for ‘a lark’.

Making a new man of himself

It was during his years at Jesus (1927–32) that Alfred Alistair Cooke (1908–2004) from Blackpool reinvented himself as Alistair Cooke of Manchester, growing a moustache and grinding out all trace of a Northern accent. Talented as a caricaturist and composer, Cooke edited Granta and established The Mummers, the first Cambridge drama group to accept women. Unsurprisingly, given these distractions, Cooke failed to get the expected First. Elizabethan literature expert E M W Tillyard (1889–1962) spoke more truly than he knew when he dismissed Cooke for his ‘journalist’s mind’. His tutor noted likewise – ‘very much out for himself, a clever careerist’. Desperate to stay on, Cooke failed to survive by tutoring and writing, but avoided schoolmastering thanks to the newly-established Harkness Scholarship scheme, which enabled him to escape to Yale to study theatre production. The rest is, indeed, history, much of which Cooke witnessed and reported first-hand and some of which, in broadcasting terms, he made. Cambridge eventually revised its jaundiced impressions but waited until he was 79 to award him an honorary degree.

‘The Great George’

George Macaulay Trevelyan (1876–1962) was to become the most well-known British historian of his generation. Born of a distinguished lineage, the great-nephew of Thomas Babington Macaulay, Trevelyan became an ‘Apostle’ and a Fellow of Trinity. Proclaiming history as a branch of literature, he believed it should be written not for fellow academics, but for the public. His own dissertation was sufficiently readable to be published as England in the Age of Wycliffe (1899). By the time his equally popular England Under the Stuarts (1904) was published he had abandoned Cambridge for London and a literary career. An Italophile, he made his name with a three-volume biography (1907–11), of Giuseppe Garibaldi, hero of the Risorgimento.

Trevelyan then played a leading role in the 1922–6 Royal Commission, which reorganised the governance of Oxford and Cambridge. Returning to Cambridge in 1927 as Regius Professor of History, he produced his magnum opus, a three-volume account of England Under Queen Anne. A Northumbrian squire by background, the tall, wiry Trevelyan was a formidable walker and like his hero, Macaulay, believed passionately in treading the very soil where Garibaldi had bled and Marlborough had directed his great victories. In 1940 Trevelyan was chosen by Churchill to become Master of Trinity. His popular masterpiece, English Social History (1944), written against the background of a struggle for national survival, was a reassuring account in which England itself is the silent hero – in the words of a medieval poet, ‘a fair field full of folk’. Trevelyan’s tenure as Master of Trinity was extended by his colleagues to the maximum permissible. He could have been Director of the London School of Economics, President of the British Academy or Governor-General of Canada, but was content enough to remain as a Fellow of the Royal Society, a Fellow of the British Academy and holder of the Order of Merit.

An English revolution?

‘… a general insensitivity to poetry does witness a low level of general imaginative life…’

Ivor Armstrong Richards

Between them, two Magdalene dons, C K Ogden (1889–1957) and I A Richards (1893–1979), transformed the teaching of English as both a language and a body of literature.

Both a linguist and a psychologist, Ogden, founder of the Heretics Society, also established the highly influential Cambridge Magazine, a penny weekly journal of comment that had sold 20,000 copies by 1918. In 1922 he translated Wittgenstein’s Tractatus and, jointly with Richards, published The Meaning of Meaning (1923), an enquiry into how language can be used with greater precision and understanding. Inspired by the little-known contribution of the philosopher Jeremy Bentham (1748–1832) to linguistics, Ogden, with Richards’s aid, created Basic English as ‘an auxiliary international language comprising 850 words arranged in a system in which everything may be said for all the purposes of everyday language’. The vocabulary, 60% of which consisted of single syllable words, included just 18 verbs. During World War Two Churchill pledged to promote its use, via the British Council and the BBC, as an element of British cultural policy, arranging for the Crown to buy out the copyright, thus enabling Ogden to indulge his bibliomania. After selling off his valuable collections, Ogden still left 100,000 volumes at his death.

Richards, a celebrated mountaineer despite a severe early bout of tuberculosis, made his reputation with Principles of Literary Criticism (1924) and Practical Criticism (1929), which, according to the Oxford Companion to Literature ‘revolutionised the teaching and study of English’. Both derived from Richards’s key teaching technique of distributing unattributed poems to students and analysing their written reactions to ‘the words on the page’ – sounds, rhythms, sentence structures. He was appalled to discover that many found the works of Donne or Gerard Manley Hopkins less appealing than the effusions of the Bard of the Trenches, ‘Woodbine Willie’. George Orwell – an Etonian but not a university man – found this revelation hugely amusing – ‘For anyone who wants a good laugh … I recommend I A Richards’s Practical Criticism.’

Richards became a crusader against the critical failings of vagueness, laziness and sentimentality and for an appreciation of complexity, allusiveness, irony and ambiguity. Emphasising close reading to the exclusion of biographical, social and historical context, Richards became the father of ‘textual studies’, whose doctrines were to be developed by his student William Empson and partial disciple F R Leavis (see below). Richards’s later career included extended periods teaching in China and at Harvard and writing works on Mencius, Coleridge and Plato, as well as his own, late, poetry. A Senate House memorial ceremony in 1979 featured white silk funeral banners sent in respect by the Chinese government.

English with attitude

‘… a magnificent, acid, malevolently humorous little man who looks exactly like a bandy-legged leprechaun.’

Sylvia Plath, 1955

The achievement of F R Leavis (1895–1978) was not so much to revolutionise literary criticism as to make it a quasi-religious cult. Born in Cambridge and educated at the Perse School, Leavis won a history scholarship to Emmanuel, switched to English, took a First and completed a doctorate on journalism and literature. In 1929 Leavis married the formidable Queenie Roth, a ferociously bright product of Jewish North London’s intellectual enclave, Hampstead, and an expert on the history of working-class readership. Together they produced (1932–53) the literary journal Scrutiny as a vehicle for their views.

Scorning neckties and carrying his battered texts in a garden sack rather than a briefcase, Leavis was as much preacher as teacher; as concerned with what one should not read as with what one should. Rupert Brooke, he dismissed as exhibiting ‘Keats’s vulgarity with a public school accent’. Part of Leavis’s attraction was that, in contrast to the languorous ambivalences of so many dons, he offered burning certainties, attracting not pupils but disciples – on whom he often turned with venom. As Clive James (1939–) has noted, ‘the Leavisite brand of odium theologicum had all the characteristics of totalitarian argument, right down to the special hatred reserved for heretics.’

As a disciple of I A Richards, Leavis discarded the narrative tradition of literary history in favour of close textual analysis. Loathing Marxism, materialism and mass media, contemptuous of advertising and technology, he believed that the true history of the English had been written by its great novelists, notably George Eliot (1819–1880). This was still true for authors such as Henry James and Joseph Conrad (1857–1924), who were not even English. Through appreciative analyses in Scrutiny, in the lecture room and as a provocative speaker at student literary gatherings, Leavis promoted the work of James Joyce (1882–1941), T S Eliot (1888–1965) and D H Lawrence (1885–1930) when their names were scarcely known, let alone part of any canon; likewise the poetry of Gerard Manley Hopkins (1844–1889), W B Yeats (1865–1939) and Ezra Pound (1885–1972).

Leavis remained controversial in Cambridge to the end, excluded from the English faculty until he was past 40 and from its board until almost 60, and only appointed Reader on the eve of retirement. Outside Cambridge it was different. Leavis’s impact on generations of teachers of English was incalculable. He was awarded five honorary degrees and made a Companion of Honour. To the end he remained unshaken in his belief that in an age of cultural barbarism the university must be ‘more than a collocation of specialist departments … a centre of human consciousness: perception, knowledge, judgment and responsibility’; and at the heart of the university must be ‘a vital English school’. Though Leavis, of course, believed that that school was to be found in the pages of Scrutiny – ‘the essential Cambridge, in spite of Cambridge’. The music shop of Leavis Senior, opposite the gates of Downing College, is now a branch of Pizza Hut.

Young Turks

The inter-war years were a golden age for Cambridge science. Professorships were established in newly-recognised fields including aeronautical engineering, mineralogy and petrology, animal pathology and biochemistry.

At the Cavendish, J J Thomson was succeeded as head by his first ever research student, the New Zealander Ernest Rutherford (1871–1937), who is claimed by The Cambridge Dictionary of Scientists to have ‘founded nuclear physics’. He had already been awarded the Nobel Prize for Chemistry in 1908. Rutherford was the first to describe the structure of the atom correctly, to predict the existence of the neutron and to collaborate with colleagues to bring about the first nuclear fusion reaction. Energetic and charismatic, Rutherford attracted a galaxy of young talent to Cambridge, making it the world centre for what he called, in the title of his last book, The Newer Alchemy.

If the younger Leavis can be said to have had a scientific counterpart it was J D Bernal (1901–1971), nicknamed ‘Sage’ while still an undergraduate at Emmanuel. In a decade at the Cavendish, he played a major role in the development of crystallography, with ground-breaking investigations into the structure of viruses and proteins, and became ‘the founding father of molecular biology’. Bernal’s extraordinary range of interests also led him to undertake pioneering work in the history of science. Max Perutz remembered Bernal’s sub-department – ‘housed in a few ill-lit and dirty rooms … These dingy quarters were turned into a fairy castle by Bernal’s brilliance’. Nobel Laureate Dorothy Hodgkin (1910–1994) recalled lunchtime picnics in the lab when the conversation ranged from anaerobic bacteria to Romanesque architecture or Da Vinci’s ‘engines of war’. Elected a Fellow of the Royal Society at 36, Bernal, a lifelong Communist, played a key role as a top-level scientific adviser during World War Two and earnt the unusual distinction of being the recipient of both the United States Medal of Freedom and the Lenin Prize for Peace.

The Westminster Abbey memorial to Paul Dirac (1902–1984) was the first to carry an equation as part of its inscription and lies next to that of his predecessor as Lucasian Professor of Mathematics, Sir Isaac Newton. Dirac is the founding father of quantum mechanics, which explains phenomena as various as why the stars shine and how transistors work. It was also Dirac who predicted the existence of ‘anti matter’. Appointed to the Lucasian chair at just 30, a year later Dirac shared the Nobel Prize for Physics with Erwin Schrödinger (1887–1961).

‘And I remember Spain’

Born in December 1915, Rupert John Cornford (1915–1936) was named after Rupert Brooke, who had died in April of that year. Cornford’s mother, the poet Frances Cornford (1886–1960), was a granddaughter of Charles Darwin; his father, confusingly, was the classicist Professor Francis Cornford. Frances Cornford was an admirer of Brooke’s poetry, as well as a personal friend. Her son came to despise the whole ‘Georgian’ school of poetry and, rejecting the association with Brooke, insisted on using his second given name. During three years at Trinity, Cornford devoted most of his waking hours to Communism but still managed to collect a First in both parts of the historical tripos. He also fathered an illegitimate son but abandoned both the child and its mother on discovering the love of his life in Newnham history student Margot Heinemann (1913–1992).

When civil war broke out in Spain in July 1936, Cornford, with no Spanish, left at once, without telling even his family, to become the first Englishman in the International Brigade. A serious head wound during the battle for Madrid curiously rekindled his impulse to write and over a few weeks he produced memorable work, notably Heart of the Heartless World. John Cornford was killed in a shambolic skirmish near Lopera, probably on his 21st birthday.

Britain’s leading Communist agitator, Harry Pollitt (1890–1960), observed brutally, if rationally, that Cornford’s death was a great loss to the Communist cause as it had Welsh miners to spare but precious few first-class intellectuals. Cornford’s son, James, was adopted and brought up by his own parents. Margot Heinemann eventually had a daughter with J D Bernal, remained a Communist until the dissolution of the Communist Party of Great Britain and was still teaching at New Hall at 76.

Cornford’s sacrifice was not unique. Julian Bell (1908–1937), nephew of Virginia Woolf, returned from teaching English in China to take up the Spanish cause. Whereas Cornford had lived in bare-light-bulb austerity, Bell had enjoyed having ‘a car, and my own rooms, furniture, pictures – all the amenities of Cambridge at its best’. When he was invited to join the Apostles ‘I felt I had reached the pinnacle of Cambridge intellectualism’. He had. Four years dissipated on two dissertations failed to secure him a King’s fellowship – hence the odyssey to Wuhan. Respect for his mother’s pacifist principles led Bell to become an ambulance driver in Spain but he was killed at the battle of Burete, aged 29.

David Haden-Guest (1911–1938), a leading light of the Moral Sciences Club, decorated his Trinity room with a picture of Lenin. Studying in Germany, he became an active anti-Nazi, and later taught mathematics in Moscow. Haden-Guest was also killed in action with the International Brigade in Spain. A Textbook of Dialectical Materialism, based on notes from his lectures to workers at a Marx Memorial School, was published posthumously.

The enemies within

While the Communist Cornford fought Fascism to die in a foreign country, a clique of his Cambridge contemporaries opted to fight Fascism by betraying their own. Self-assigned servants of a supposedly larger patriotism, they were recruited as agents of the USSR. Flamboyant Etonian and Apostle, Guy Burgess (1910–1963) of Trinity penetrated the British establishment via the BBC, MI6 and the Foreign Office until he arranged to be recalled from the British Embassy in Washington DC for ‘serious misconduct’ in 1951 when he believed himself to be under suspicion. Burgess then ‘disappeared’, only to re-emerge in 1956 in Moscow, where he died of alcoholism in 1963. Burgess’s closest collaborator, Donald Maclean (1913–1983), recruited as a spy by Anthony Blunt while still an undergraduate, took a First in Modern Languages at Trinity Hall and rose through the Foreign Office ranks to betray secrets about Britain’s atomic programme and the formation of NATO before fleeing with Burgess in 1951, also turning up in Moscow where he became a colonel in the KGB. As head of British counter-espionage, charged with combatting Soviet subversion, ‘Kim’ Philby (1912–1988) was uniquely placed to betray many agents and pass on CIA secrets to the USSR. He also tipped off Burgess and Maclean that they had come under suspicion and should flee. Sacked in 1955, Philby evaded arrest, eventually fleeing to the USSR in 1963, where he was granted political asylum. The mannered Anthony Blunt (1907–1983), another Apostle and a Fellow of Trinity, limited his betrayals to wartime service with MI5 and pursued a glittering career as Britain’s leading art historian. Appointed to take charge of the royal picture collection in 1945, he also became the director of the Courtauld Institute of Art in 1947, a post he held for the subsequent 27 years. Having made a secret confession in return for immunity from prosecution in 1964, Blunt was not publicly unmasked until 1979, when he was stripped of his knighthood. A ‘fifth man’ was eventually identified as John Cairncross (1913–1995), another brilliant linguist who worked as a code-breaker at Bletchley Park and passed almost 6,000 documents to the USSR. Cairncross, a Scot who did not share the public school background of the other four, worked independently of them. His exposure obliged him to reinvent himself as a professor of French literature in the USA and then a translator in Italy before marrying an opera singer in the year of his death at the age of 82.

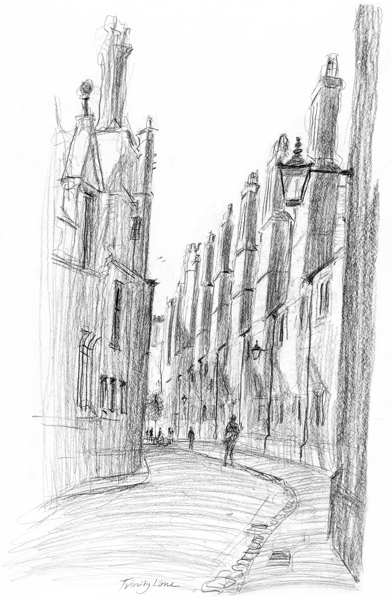

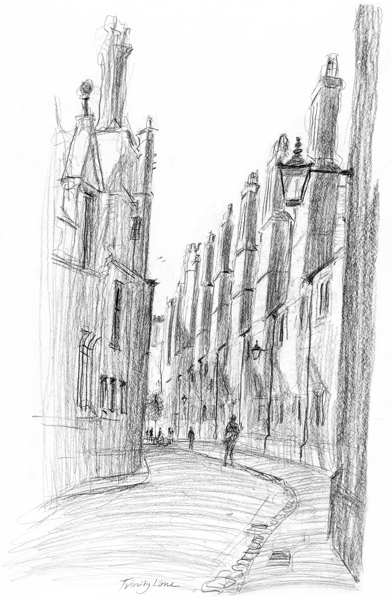

Trinity Lane

Quest for certainty

The intellectual odyssey of Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889–1951), seeking the limits of the thinkable, was mirrored in a life bereft of stability. Austrian by birth, originally trained in mechanical engineering, he studied aeronautics at the University of Manchester until a deepening interest in mathematics led on to philosophy and Cambridge in 1912 to study under Bertrand Russell. After five terms Wittgenstein left to become a recluse in Norway, a decorated artillery officer in the Austro-Hungarian army, a prisoner of war, a village primary school teacher, a gardener’s labourer and a self-taught architect. Returning to Cambridge in 1929, Wittgenstein offered for his PhD thesis his most celebrated work, the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, running to just 75 pages. This gained him both a doctorate and a fellowship at Trinity. In 1939 he succeeded to the chair of philosophy previously occupied by George Edward Moore (1873–1958).

Wittgenstein’s attempts at a clarification of thought through a critique of language led to a questioning of such basic philosophical terms as ‘proposition’, ‘rule’ and ‘knowledge’. His teaching was an agonised process of self-interrogation and self-accusation which left his listeners enthralled or bewildered, and Wittgenstein himself drained; the ordeal immediately exorcised by a trip to one of the Cambridge flea-pit cinemas and a hasty pork pie. Interestingly, while he taught in English he still wrote in German – beautifully. Having become a British citizen in 1938, on the outbreak of war Wittgenstein forsook the comforts of Trinity to work as a porter in Guy’s Hospital in Blitz-torn London and as a laboratory assistant in Newcastle. He returned briefly to Cambridge after the war but quit teaching in 1947. His Philosophical Investigations, published posthumously in 1953, essentially contradicted the position he presented in the Tractatus.

‘… little more than a towering bookstack’

Described as looking like a cross between a ‘warehouse and an Assyrian palace’, a ‘motor factory or steam laundry’, the University Library was built between 1931 and 1934 to the designs of Sir Giles Gilbert Scott. The 156-foot tower which looms over the surrounding countryside was imposed on the original design at the insistence of the American benefactor who stumped up half the cash needed for the project. As its steel skeleton rose inexorably higher, contemporaries discussed whether or not it was ‘a Mistake’, opinions varying from ‘eye-sore’ to ‘beautiful – in its own way of course but definitely beautiful’ to ‘admirable in any place but this.’ The entire stock of the University Library – 1,142,000 books – was transferred from the Old Schools site in 689 loads, during eight weeks of the Long Vacation of 1934, by Library staff and porters hired from Eaden Lilley’s department store. Horse-drawn vans were preferred over motor trucks to maintain an even pace between those loading and those unpacking.

Cambridge University Library prides itself on being the largest open-access library in Europe, with some two million volumes available to readers. Placed end to end, the shelves would stretch from Cambridge to Brighton. As the historian Piers Brendon notes, the freedom to browse creates endless opportunities for ‘that incomparable tool of academic research, serendipity’, whereas in Oxford’s Bodleian library ‘you have to know what you are looking for in order to request it and it takes time to arrive.’ The UL also accommodates the entire libraries of Peterborough Cathedral and the Royal Commonwealth Society and the 70,000 volumes collected by Lord Acton. Its other treasures range from Chinese oracle bones dating from 1200 BC to the 14,000 letters of the Darwin Archive. And every week as a result of its status as one of six ‘copyright libraries’ in the British Isles it receives some 1,500 books, 2,000 issues of periodicals and hundreds of maps and pieces of sheet music to add to its collections … plus 70,000 monographs and dissertations a year … plus any purchases that might be made around the world. Once an item comes into the possession of the Library it is never for sale.

New buildings, not noticeably new architecture

Despite the unfavourable economic background of the inter-war depression, many colleges undertook building projects, Clare’s Memorial Court being perhaps the boldest and most coherent. In 1922–3 Jesus added a small corner range to Second Court. Garden Court was built at Sidney Sussex in 1923–5. In 1925–6 Magdalene undertook one of the most imaginative and successful schemes in the city, creating Mallory Court by adding new buildings to existing medieval cottages. In 1927 King’s removed the railings along its frontage and replaced them with the low wall that generations of tourists have sat on ever since. In 1930–2 the doyen of the British architectural profession, Sir Edwin Lutyens, designer of celebrated country houses and the Cenotaph, added a range to Benson Court at Magdalene. In 1929–32 his collaborator in designing New Delhi, Sir Herbert Baker, added the north range to Downing College.

The pace of construction quickened in the 1930s. Selwyn built a library (1930), Jesus a south range to Chapel Court (1931), Girton Woodlands Court (1931), Pembroke a new Master’s Lodge (1932–3) and Trinity Hall two new ranges in North Court (1934). In 1934 Caius’s new hostel facing onto Market Hill became one of the earliest modern buildings in the city centre. At Queens’, Fisher Court (1935–6), west of the Cam, employed a conventional architectural style (‘suburban Tudor’) but followed an unconventional curving plan to create unforeseen restrictions on the future development of the area to its north; it is notable, however, as the first college building with the luxury of bathrooms and lavatories near students’ rooms, rather than across some chilly courtyard. In 1936 St Catharine’s added a west range to Sherlock Court. Sidney Sussex built a range along Sussex Street in 1937–9. Newnham put up its Fawcett Building (1938) and St John’s finally (1938–40) completed its Chapel Court, North Court and Service Court. Along the west side of Bridge Street the college also demolished 18 houses and shops, Warren’s Yard, Sussum’s Yard and Coulson’s Passage to make way for a new music school – and bike sheds.

University projects were limited to the Department of Pathology (1927) and the Scott Polar Research Institute (1933–4), another effort by Sir Herbert Baker.

The most significant municipal undertaking was the rebuilding of the Guildhall (1939) to the designs of Charles Cowles-Voysey – perhaps a riposte to the county’s new (1932) Shire Hall on Castle Hill on the site of the old County Gaol. In 1934 the borough boundaries were extended to embrace both Cherry Hinton and Trumpington. In 1936, as if in acknowledgment of the demolitions wrought in the name of progress, the 16th century White Horse Inn was converted into a museum of folk history. A Cambridge Preservation Society had come into existence in 1928.

In 1922 the Cambridge Evening News complained that ‘for three months of the year Cambridge is almost a deserted city and trade dwindles to a mere trickle.’ A rapid expansion of motor traffic was, however, soon to promote both prosperity and problems. The town undertook numerous road-widening schemes, as at Jesus Lane (1922) and along Bridge Street (1938). Drummer Street was redeveloped in 1925 to create a major bus depot and space for car parking. Other measures included the introduction of one-way streets from 1925, and the provision of more parking space in New Square in 1932. The river crossing at Fen Causeway was undertaken in 1926, providing 90 jobs for recruits from the ranks of the unemployed. The university made its own, characteristically negative, contribution by imposing severe limitations on the ownership of motor cars by the student population.

To cope with the increasing number of visitors to Cambridge the University Arms Hotel added a large extension to its rear. National retailing chains in the form of Woolworth’s, Marks & Spencer, Boot’s and Sainsbury’s also opened branches in Cambridge. Local businesses succumbed to the competition; the 16 breweries existing in 1900 were reduced to six by 1925. Stourbridge Fair finally petered out. In 1931, as the nation entered the depths of depression, Cambridge acquired a quite novel entertainment venue – The Dorothy. In its basement was a pub, The Prince of Wales, on the ground floor a shop and restaurant, on the first floor a dance hall, on the second a dining hall and at the top a roof garden.

The movies increased in popularity among both students and townsfolk. In 1925 a second purpose-built cinema, the Tivoli, was opened on Chesterton Road and in 1930 the Central cinema on Hobson Street was rebuilt. In 1931 the Victoria cinema opened where Marks & Spencer now stands and in 1937 another establishment, the Regal, was opened. In the same year Cambridge elected its first ever Labour Mayor, who bore the uncompromisingly proletarian name of Bill Briggs. Communists in the university surprised few – but a Labour mayor!

In 1575 William Soone, formerly Regius Professor of Civil Law, recorded that ‘to beguile the long evenings’ in the depths of winter, students ‘amuse themselves with exhibiting public plays, which they perform with so much elegance, such graceful action, and such command of voice, countenance and gesture, that if Plautus, Terence or Seneca, were to come to life again, they would admire their own pieces and be better pleased with them than when they were performed before the people of Rome.’

In 1579 Richardus Tertius, a play about Richard III, written by Thomas Legge (1535–1607), Master of Caius, was performed in the hall of St John’s. The great dining hall at Trinity, built in 1608 by Thomas Nevile, was clearly intended for periodic use as a theatre. Historian Patrick Collinson, indeed, claims it as ‘England’s oldest surviving theatre’, no less. The most common Tudor and Jacobean fare was comedy – in Latin – mostly by Terence. In 1614 James I braved wintry weather to trek over from Newmarket to see four plays on four nights, including Ignoramus, a satire on lawyers. Despite the fact that the piece took six hours to get through, James loved it, and came back two months later for an encore performance.

Thomas Heywood (c.1570–1641), himself a Cambridge undergraduate in the 1590s, argued in An Apology for Actors (1612) that performing in plays was a useful training for the world of public affairs ‘emboldening … junior scholars, to arm them with audacity, against they come to be employed in any public exercise’. The commercial stage, however, was frowned on by the university authorities, who even banned the townspeople from watching puppet-shows, although Stourbridge Fair offered the more exotic attractions of rope-dancers, fireworks and freak-shows. Touring companies of actors trying their luck in Cambridge were either paid off or seen off. Since the repeal in the 1850s of statutes banning drama, the atmosphere has changed somewhat…

THE ADC

Cambridge University Amateur Dramatic Club was founded in 1855, making it England’s oldest university theatre group. It is still the largest in Cambridge. The core support came from Trinity, its leading light 19-year-old Francis Cowley Burnand (1836–1917), the first of many subsequent students to devote more time to the stage than study. In his case it paid off. Scotching family plans for the Anglican priesthood by becoming a Catholic, qualifying for the bar but declining to practise, Burnand wrote over 100 pieces for the stage, enjoyed a great hit with Black-Eyed Susan (1866), edited Punch for 26 years and ended his days as Sir Francis Cowley Burnand, patriarch of 13 offspring.

The ADC was fortunate early in its existence to find permanent premises in the Hoop, a former coaching inn on Park Street, whose business had been badly hit by the coming of the railways. Until the 1920s the standard theatrical fare was the sort of lightweight stuff that Burnand had proved so adept at turning out. After it became home to the Marlowe Society (see below), the Club began to engage with Elizabethan texts and other classic works.

The ADC was burnt down in 1933 but, thanks to widespread popular support, rebuilt within 18 months. Women were permitted on the stage from 1935 onwards. Threatened with bankruptcy in 1974, it was taken over by the university and nowadays is technically its smallest department. Membership is not, however, limited to members of the university but is open to all full-time students in Cambridge.

ADC alumni have included four Directors of the Royal National Theatre (Sir Peter Hall, Sir Trevor Nunn, Sir Richard Eyre and Sir Nicholas Hytner) as well as the late Sir Michael Redgrave (1908–1985), Sir Derek Jacobi, Sir Ian McKellen, Sam Mendes, Simon Russell Beale and Rachel Weisz. (www.cuadc.org)

The Marlowe Society

The Marlowe Society was founded in 1907 to revive interest in the Elizabethan and Jacobean theatre, no Shakespeare having been performed in Cambridge since 1886. The Society’s first production was Dr Faustus, featuring the newly-arrived Rupert Brooke. In 1922 the Society presented a milestone production of Troilus and Cressida. Soon after it became the special directorial province of the charismatic ‘Dadie’ Rylands (see below). James Mason (1909–1984) of Peterhouse took a First in Architecture in 1931 but it was the reception given to his performance that year as Flamineo in the Society’s production of The White Devil that encouraged him to abandon the drawing-board for the boards. By 1944 James Mason was Britain’s top box-office star and would eventually appear in more than 100 films. In 1948, at the height of the Berlin Blockade, when Stalin sent the Red Army Choir to the German capital on a propaganda tour, the British Council riposted by dispatching Rylands and the Marlowe Society to play Measure for Measure and The White Devil. Between 1957 and 1964 Rylands and the Society responded by obliging the BBC to record all of Shakespeare’s works to mark the 400th anniversary of his birth. In 1977 Griff Rhys Jones enjoyed spectacular success with Ben Jonson’s Bartholomew Fair, as Sam Mendes did with Rostand’s Cyrano de Bergerac in 1988. In 1993, to mark the 400th anniversary of Marlowe’s murder, Robin Chapman produced Chistoferus or Tom Kyd’s Revenge.

Footlights

Footlights’ alumni have included John Cleese, Sir David Frost, Michael Frayn, Sir Jonathan Miller, Peter Cook, Bill Oddie, Clive Anderson, Tim Brooke-Taylor, Stephen Fry, Hugh Laurie, Nick Hancock, Steve Punt, David Baddiel, David Mitchell and Sacha Baron Cohen, not to mention numerous bishops and MPs, several Professors of Music, one of Mrs Thatcher’s speechwriters, an Attorney-General, a chairman of the International Olympic Committee, a Lord Keeper of the Great Seal of Scotland and the author of The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. Since the 1960s, at least, dozens of applicants have applied to Cambridge less to get into the university than to get into Footlights.

Footlights was established in 1883 and gave its first public performance – which included a cricket match – to the inmates of a Cambridge pauper lunatic asylum. In 1885 it put on its first original operetta Uncle Joe at Oxbridge. Since 1892 it has only staged original material. In 1897 Footlights presented an imaginative spoof portraying Cambridge in the year 2000, The New Dean. A rich American benefactor saves the university from ruin at the cost of imposing a feminist regime and himself marries the female Vice-Chancellor. The new – female – dean breaks all the rules by marrying an undergraduate. The Bedmakers Union protest at this breach of propriety by striking until their leader replaces the Dean and employs her as her maid. Male dons meanwhile are redeployed as college servants. This vision of the future was, however, too fantastical to survive even its own denouement, as the opera ends with all the female university officials resigning voluntarily to embrace marriage instead.

Early (1910–1914) Footlights excursions onto the London stage lampooned socialism and vegetarians but donated takings to children’s charities and the blind. In 1913 a Caius oarsman, Jack Hulbert (1892–1978), notched up an early success with his musical comedy, Cheero Cambridge, and went on to become a major inter-war star of stage and screen. In 1936 Footlights staged the first of 53 revues at the Arts Theatre. By the 1950s, BBC TV and Radio were broadcasting extracts from Footlights productions and transfers to the London stage were regularly lasting three weeks. In 1957 women were at last admitted – since when the names of Miriam Margolyes, Eleanor Bron, Julie Covington, Germaine Greer, Emma Thompson, Sue Perkins and Sandi Toksvig have been added to the roll-call of alumnae. In 1963 Cambridge Circus made it to New York and New Zealand. Clive James led a successful assault on the Edinburgh Fringe in 1967.

Footlights has had various homes, all more or less cramped and scruffy. In Clive James’s day it was above a fish shop in Petty Cury. Stephen Fry remembers ‘a dank, pine-clad hovel in the Union Society’s bowels’. Now it has no specific home of its own, but regularly mounts ‘smokers’ (from informal revues where smoking was allowed), a Christmas pantomime, a spring revue and a summer touring show. For a more extensive account see www.footlights.org and Robert Hewison, Footlights: A Hundred Years of Cambridge Comedy (1983).

The Arts Theatre

The Arts Theatre, opened in 1936, was the brainchild of J M Keynes, who also saw to its financing and establishment. Of the £32,000 required, Keynes provided nearly £30,000 and eventually got only £17,000 of it back. In the opening season Keynes’s wife, the Russian ballerina Lydia Lopokova, took the leading parts in Ibsen’s A Doll’s House and The Master Builder. As a small boy, Sir Peter Hall stood at the back, for sixpence, watching Sir John Gielgud (1904–2000) play Hamlet. The Arts has not only provided a venue for Footlights and the Marlowe Society, but also for visiting companies, opera, ballet and previews of London productions. It was completely rebuilt in 1995–1997 at a cost of some £10,000,000.

‘Dadie’ Rylands: ‘not merely a performer, but a celebrity’ – Lord Annan

There was once a don at King’s whose pupils and protégés included the ADCs roll-call of theatrical knights (Hall, Nunn, Jacobi, McKellen) and whose talents as a director or lecturer were sought out by the Old Vic, the BBC and the British Council. George Humphrey Wolferstan Rylands (1902–1999) was universally known as ‘Dadie’, from his childhood mispronunciation of ‘baby’. A stylish rather than a penetrating lecturer, whose subject-matter ranged from Shakespeare, Dryden and Pope to problems of translation and the influences of Greek and Latin on English style, Rylands was also an inspiring teacher in tutorials. Himself the son of a West Country land agent, he proved an unexpectedly capable wartime administrator of King’s complex property portfolio, as well as being for decades a mainstay of the Marlowe Society and the Arts Theatre. Having made a stunning debut in 1921 in King’s annual Greek play, 20 years later he would astonish donnish colleagues playing the title roles in wartime productions of Othello and King Lear. As a director Rylands’s preoccupation was, in Ian McKellen’s words, to instill in actors ‘the most scrupulous attention to the classic texts, transforming their understanding’ and to set an impeccable standard for the speaking of blank verse.

Rylands’s doctoral thesis became his first book, Words and Poetry (1928), in which he argued that the impact of verse is on the ear before the brain, making it a matter of music, rather than of morals; he consequently detested the brutal judgmentalism of Leavis. 1928 was also the year in which Rylands moved into the rooms at the Old Provost’s Lodge which were to be his home until his death. Bloomsbury artist Dora Carrington (1893–1932) decorated the doors and fireplaces. Despite her judgment that they looked like the work of a sick mouse (blaming too many cocktails), they are now lovingly treasured. Rylands entertained Virginia Woolf to lunch there that same year, a crucial incident recorded in her famous essay A Room of One’s Own.

Rylands’s most influential book was a Shakespeare anthology, widely carried by servicemen during World War Two, which subsequently became the basis for Gielgud’s bravura one man stage show, The Ages of Man. Etonian, Apostle, CBE and Companion of Honour, in youth ‘miraculously blond’, in old age wealthy enough to give a fortune to his college, university and beloved Arts Theatre, Dadie Rylands was also prone to self-destructive drunkenness, devastated by the death of his adored mother, guilt-ridden by his homosexuality and allegedly aged ten years by the exposure of his friend Anthony Blunt as a spy. As Lord Annan pointedly asked the year after Rylands’s death – what would the government’s new-fangled assessment exercise have made of his ‘academic career’? – ‘Where were the books … what had he been doing? Play-acting? Surely we want stout volumes … not a succession of ephemeral activities.’ Would the idea that he had not only have exerted a seminal influence on English theatre, but enhanced the culture of the entire country, even have crossed their minds?