FREE TO BE HAPPY

The Declaration of Independence enshrined the pursuit as everyone’s right. But the founders had something much bigger than bliss in mind

BY JON MEACHAM

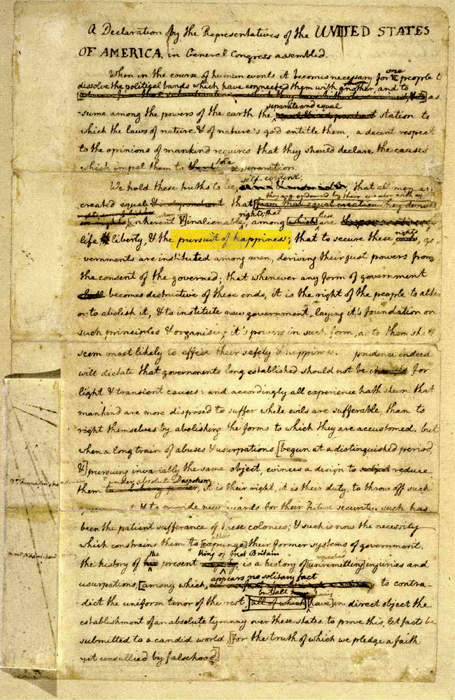

THE DRAFT

A committee tasked with writing what would become the colonies’ Declaration of Independence chose Jefferson to write the draft. The document was submitted to the Continental Congress on June 28, 1776, and adopted on July 4. The phrase “pursuit of happiness” appeared in each version of the text

SITTING IN HIS SMALL two-room suite in the bricklayer Jacob Graff’s house at Seventh and Market Streets in Philadelphia—he hated the flies from nearby stables and fields—Thomas Jefferson used a small wooden writing desk (a kind of 18th century laptop) to draft the report of a subcommittee of the Second Continental Congress in June 1776. There were to be many edits and changes to what became known as the Declaration of Independence—far too many for the writerly and sensitive Jefferson—but the fundamental rights of man as Jefferson saw them remained consistent: the rights to life, to liberty and, crucially, to “the pursuit of happiness.”

To our eyes and ears, human equality and the liberty to build a happy life are inextricably linked in the cadences of the Declaration, and thus in America’s idea of itself. We are not talking about happiness in only the sense of good cheer or delight, though good cheer and delight are surely elements of happiness. Jefferson and his colleagues were contemplating something more comprehensive—more revolutionary, if you will. Garry Wills’ classic 1978 book on the Declaration, Inventing America, puts it well: “When Jefferson spoke of pursuing happiness,” wrote Wills, “he had nothing vague or private in mind. He meant public happiness which is measurable; which is, indeed, the test and justification of any government.”

The Virginia Declaration of Rights—drafted in 1776 by George Mason and considered a model for the Declaration of Independence—spoke of “pursuing and obtaining happiness and safety.” It also named “acquiring and possessing property” among the “inherent natural rights,” phrasing that would not be echoed by Thomas Jefferson

THE MODEL

George Mason

The idea of the pursuit of happiness was ancient, yet until Philadelphia it had never been granted such pride of place in a new scheme of human government—a pride of place that put the governed, not the governors, at the center of the enterprise. Reflecting on the sources of the thinking embodied in the Declaration, Jefferson credited “the elementary books of public right, as Aristotle, Cicero, Locke, Sidney, & c.”

As with so many things, then, to understand the Declaration we have to start with Aristotle. “Happiness, then,” he wrote, “is ... the end of action”—the whole point of life. Scholars have long noted that for Aristotle and the Greeks, as well as for Jefferson and the Americans, happiness was not about yellow smiley faces, self-esteem or even feelings. According to historians of happiness and of Aristotle, it was an ultimate good, worth seeking for its own sake. Given the Aristotelian insight that man is a social creature whose life finds meaning in his relation to other human beings, Jeffersonian eudaimonia—the Greek word for happiness—evokes virtue, good conduct and generous citizenship.

As Arthur M. Schlesinger Sr. once wrote, this broad ancient understanding of happiness informed the thinking of patriots such as James Wilson (“the happiness of the society is the first law of government”) and John Adams (“the happiness of society is the end of government”). Once the Declaration of Independence was adopted and signed in the summer of 1776, the pursuit of happiness—the pursuit of the good of the whole, because the good of the whole was crucial to the genuine well-being of the individual—became part of the fabric (at first brittle, to be sure, but steadily stronger) of a young nation.

The thinking about happiness came to American shores most directly from the work of John Locke and the Scottish-Irish philosopher Francis Hutcheson. During the Enlightenment, thinkers and politicians struggled with redefining the role of the individual in an ethos so long dominated by feudalism, autocratic religious establishments and the divine rights of kings. A key insight of the age was that reason, not revelation, should have primacy in human affairs. That sense of reason was leading Western thinkers to focus on the idea of happiness, which in Jefferson’s hands may be better understood as the pursuit of individual excellence that shapes the life of a broader community.

Like, say, the newly emerging United States of America. Pre-Jefferson, the precept was explicitly expressed in the newly adopted Virginia Declaration of Rights, a document written by George Mason and very much on Jefferson’s mind in the summer of 1776. Men, wrote Mason, are “equally free and independent, and have certain inherent ... rights, [among them] the enjoyment of life and liberty, with the means of acquiring and possessing property, and pursuing and obtaining happiness and safety.” Property is often key to happiness, but Mason was thinking more broadly, drawing on the tradition of the ancients to articulate a larger scope for civic life.

From John Winthrop to Jefferson to Lincoln, Americans have been defined by our sense of our own exceptionalism—a sense of destiny that has, however, always been tempered by an appreciation of the tragic nature of life. We believe ourselves to be entitled by the free gifts of nature and of nature’s God—of our Creator, in a theological frame—to pursue happiness. What Americans don’t always let on is that we know, beneath the Rockwellian optimism and the Reaganesque confidence and the seemingly boundless faith in a democratically digital future, that we have been promised only a chance to pursue happiness—not to catch it. Americans would rather the world thought of us as Jimmy Stewarts, when there’s a strong strain of Humphrey Bogart in our national character. We’re optimists and believers, yes, but we’re practical about it, even if we don’t want you to know it.

Strictly personal happiness has its own paradoxes. Experience teaches us that the more aggressively we pursue it, the harder it can be to find. (Ask Jay Gatsby, or just about any second-term President of the U.S.) Still, there are a lot more people trying to get into this country than out of it. If it were the other way round, we wouldn’t be debating immigration the way we are.

If the 18th century meaning of happiness connoted civic responsibility, the word has occasionally been taken to be more about private gratification than public good. It’s really about both, but in some eras of U.S. history the private pursuit has crowded out the larger one. Consider the Gilded Age, the cultural excesses of the 1960s and ’70s or the materialism so prevalent in the 1980s. Whether the issue at hand is financial ambition or personal appetite, the pursuit of happiness, properly understood, is not a license to do whatever we want whenever we want if we believe it will make us happiest right then. Happiness in the Greek and American traditions is as much about equanimity as it is about endorphins.

Much is often made of the fact that Jefferson inserted “the pursuit of happiness” in place of “property” from earlier formulations of fundamental rights. Yet property and prosperity are essential to the Jeffersonian pursuit, for economic progress has long proven a precursor of political and social liberty. As Jefferson’s friend and neighbor James Madison would say, the test is one of balance and proportion. More often than not, Americans have managed to find that balance.

We must, therefore, be doing something right. The genius of the American experiment is the nation’s capacity to create hope in a world suffused with fear. And while we are too often more concerned with our own temporary feelings of happiness than we are with the common good, we still believe, with Jefferson, that governments are instituted to enable us to live our lives as we wish, enjoying innate liberties and freely enjoying the right to pursue happiness, which was in many ways the acme of Enlightenment ambitions for the role of politics. For Jefferson and his contemporaries—and, thankfully, for most of their successors in positions of ultimate authority—the point of public life was to enable human creativity and ingenuity and possibility, not to constrict it.

In 1816, Jefferson wrote John Adams about the nature of grief. Drawing on his affection for Homeric poetry, Jefferson quoted the lines from The Iliad in which Priam and Achilles come together one night shortly after Achilles has killed Hector, Priam’s son. The two sit together for a time, musing on the unhappiness of the mortal world.

Two urns by Jove’s high throne have ever stood,

The source of evil one, and one of good;

From thence the cup of mortal man he fills,

Blessings to these, to those distributes ills;

To most he mingles both.

This was the tragic Jefferson, and the tragic American. On other occasions he—and we—could refuse to accept the twilight. “Whatever they can,” Jefferson said of us, “they will.” He lived, as we do, somewhere between Homer and hope, seeking a happiness that will warm our days—and shape not only our own internal worlds, but the world around us.