WESTWARD BOUND

Thomas Jefferson commissioned Lewis and Clark to explore the vast wilderness beyond the Missouri River and chart the young country’s future. Their daring journey continues to offer lessons about how America can find its way in the world

BY WALTER KIRN

Jefferson dispatched Meriwether Lewis (left), William Clark and their Corps of Discovery on a two-year exploration of the Louisiana Purchase

THERE ARE SO MANY lessons and morals to be drawn from the expedition of Lewis and Clark that each generation tends to pick a new one according to its temperament and needs. Here is one that seems suitable: If we as Americans could see the future, we might never set to work creating it.

When they dipped their oars into the Missouri River and started rowing west through Indian country over 200 years ago, the captains were looking for something they would never find—because it wasn’t there. The Northwest Passage, the fabled missing link in a continuous navigable waterway between the Atlantic and the Pacific oceans, existed only in the explorers’ minds, but its image was enough to move them forward, and that was enough to alter history. Their adventure, like most great ones before and since, was born of equal parts hope and ignorance, sustained by fortune and determination, and consummated by an accomplishment that was unimaginable at the outset but, looking back, appears inevitable. Columbus, remember, was trying to reach India.

Cartographers were able to accurately map Lewis and Clark’s trek to the Pacific (above) based on details meticulously recorded by the explorers. In North Dakota they enlisted the aid of Sacagawea (below), a Shoshone Indian girl

What Lewis and Clark and their party finally found—although they didn’t know it at the time—was not a path between the oceans but a story whose power to challenge and absorb would bridge the more profound gap between their day and ours, between that age of new possibilities glimpsed and this one of unforeseen upheavals survived. By the time President Thomas Jefferson sent the captains up that muddy river and out of sight, the young nation already had a Constitution, but it lacked an epic. It had a government but no real identity. Lewis and Clark helped invent one.

It still lives, despite interstate highways, despite the web, despite vanishing forests, despite terrorism—despite everything. Great narratives never grow obsolete. There are much better maps of the West than those that the Corps of Discovery created, but there are still no better stories.

“If the expedition was just about a grand trip across the West, as great as that would be, it wouldn’t capture my attention or the attention of so many Americans,” says Gary Moulton, Professor Emeritus of History at the University of Nebraska and editor of the 13-volume set The Journals of the Lewis & Clark Expedition. What captivates scholars like Moulton, not to mention countless amateur history buffs, is the way the story grows and changes, adapting itself to evolving American moods.

“A hundred years ago,” says Mark Spence, a historian working with the National Park Service and the owner of HistoryCraft, which creates programs on the history of the United States, “Lewis and Clark were viewed as symbols of industrial expansion, overseas imperial trade and so on. Fifty years ago, they were really viewed as Cold Warriors in the forest; they epitomized the virtues of the company man. Today they are multicultural diplomats and proto-ecologists.”

Lewis and Clark saw themselves as Army officers. Their instructions from their Commander in Chief were clear, and the spirit behind them was practical, not poetic: claim the West and its wealth for the U.S. With Spain to the south and Britain to the north and everything in the middle up for grabs, the first American space race had begun. The expansion of knowledge was one objective—the mission was furnished with scientific instruments—but the expansion of power was its chief goal.

“Jefferson is a good man of the Enlightenment,” says James Ronda, retired professor of western American history at the University of Tulsa. “Knowledge is valued to the extent that it is useful. The yardstick here is always utility. He’ll measure a river by its navigability. He measures land by its fertility.”

The people who lived on these lands were measured too. Would the Indians help or hinder the march of progress? That was always the first question in the captains’ minds as they rounded a bend in the river and saw smoke, or glimpsed a horseman watching from a bluff. The noble cross-cultural moments came later. Before Clark helped a teenage Sacagawea give birth inside a wintry fort, and before she repaid him a thousand times over by arranging with her Shoshone kinsmen for the expedition’s passage over the Rockies, Lewis drew his sword against the Teton Sioux as they strung their bows. The whole grand endeavor might have ended right there, in the present Pierre, S.D. Had the Indians known what was coming in the years ahead, they might have wished it had.

But they couldn’t see the future either. The Indians had an illusion of their own, even more magnificently mistaken than the captains’ vision of the Northwest Passage: peace everlasting with this strange new race. The Corps carried shiny medallions to foster this dream. The coins showed President Jefferson on one side and a symbolic handclasp on the reverse.

Mutual curiosity helped too. York, Clark’s black slave, was a hit with the Indians, hamming it up to break the ice. In time, relations grew friendly, even intimate. The men of the Corps were soldiers, not saints, and their commanders were realistic men, not cartoon superheroes. Lewis carried a stockpile of medicine, including potions to treat venereal diseases. He found more than a few occasions to administer the stuff to his men.

IT IS SAID THAT ALL STORIES HAVE two sides. In the best stories, the two sides are inseparable. Pull them apart, and it makes the whole thing meaningless. “[The expedition] has that mixed quality of great news for one people and bad news for another group of people,” says Patricia Limerick, who chairs the board of the Center of the American West at the University of Colorado in Boulder. “It is not the greatest news,” she says, “to have a party of agents of empire come through.”

In the long run, Limerick is right, of course, but the Lewis and Clark expedition was really a series of short runs placed end to end until it stretched all the way to the Pacific. At a time when Americans have every reason to fear what’s waiting for them down the trail, from enemy armies to our capacity for misunderstanding and miscalculation, it’s important to remember that what’s to come is first a matter of what one does today, here, on this spot. All those footsteps will add up.

Even with the addition of Sacagawea, who had lived in the regions the expedition had yet to cross, the Corps was not always sure where it was going, but its members were keenly aware of where they stood at every important moment along the way. Lewis and Clark looked around, not just ahead—at prairie dogs in their burrows, at herds of buffalo massing in grassy valleys, at lights in the sky and seedlings in the soil.

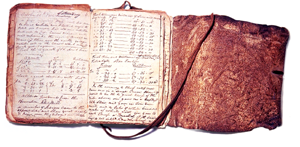

Clark filled 13 journals with sketches and notes, like this October 1805 entry on pages bound in elk skin

And they took the time to write down in their journals everything they saw. If not for the piecemeal epic the captains scratched out while crouching on hillsides and squatting on riverbanks, we might not remember Lewis and Clark at all. “There are a lot of very terse diarists in the world who say, ‘Proceeded up river and camped,’” says Limerick. “We’re very lucky to be their heirs because of their fluidity of words.”

Their words didn’t grab the nation’s attention immediately. The first edition of the journals didn’t appear until eight years after the expedition ended, in 1814. Hundreds of books later, it’s hard to imagine the absence of Lewis and Clark from the pageant of popular American history. Without them, there would still be stirring tales of exploration but none that turn on the exquisite irony of an adolescent Indian girl giving crucial advice to two male Army officers. There would still be images of frontier adversity but none so stunning as that of Lewis expecting to see a path to the Pacific but discovering endless ranks of mountains instead. There would still be historical markers on Western highways but none that lead thousands of miles to the sea and allow the pilgrim at every stop to cross-reference the vista spread out before him with the written impressions of those who blazed the trail.

“It’s the emblematic American journey,” says Ronda. “In U.S. history there is always a tension between home and the road. We talk a good talk about the joys of home, but the truth is we are obsessed with the road.”

Like every road, this one goes both ways. The country that Lewis and Clark returned through was not the same country they had just crossed. Its rivers had been named, its plants and animals sketched and classified, its native people apprised of their new status as subjects of a distant government whose claim to the place consisted of a document—the Louisiana Purchase—that none of its actual inhabitants had signed.

So that the natives wouldn’t think the Corps coveted their land, it distributed medals bearing the motto “Peace and Friendship” and, on the other side, a profile of Jefferson

The tribes reacted differently to their changed positions in the new order. The Nez Perce, who had considered killing Lewis and Clark when they first spotted them limping out of the mountains in what is now Idaho, welcomed them like lost brothers on their return trip, offering idealistic pledges of permanent friendship with the U.S., whose citizens would later repay the gesture by forcing the tribe from its hunting and grazing grounds and corralling its weakened remnants on reservations. The Blackfeet had a touchier response, perhaps because their unrivaled dominance on the northern Plains was threatened by the Americans’ plans to begin trading with neighboring tribes. One morning, while camping in what is now Montana, Lewis awoke to a struggle between an underling and an Indian who was trying to steal a rifle. Moments later, one Blackfoot brave lay fatally stabbed and another was bleeding from the gut, cut down by a bullet from Lewis’ gun.

Aside from the captains’ early floggings of disobedient underlings, this was the party’s only violent act. More remarkable, perhaps, is how much violence the explorers avoided, despite their varied ethnic and racial backgrounds and the ceaseless frustrations of the trip. It’s an inspiring thought—the melting pot on the march—but like most simple images of the famous journey, it doesn’t tell the full story, or even half of it. For every uplifting aspect of the tale, there’s a difficult, melancholy sidelight, which may well be the secret of its abiding power.

After 8,000 miles and 28 months of travel from their start near St. Louis, the Corps returned to a hero’s welcome as joyful as it was short-lived. Jefferson, according to historians, soon grew disappointed in the enterprise. It had failed to substantiate his Western dreams of a well-watered garden convenient to the Pacific where generations of self-sufficient farmers would live in democratic bliss, free from old, corrosive political controversies over issues like slavery. As for peace with the Indians and among the Indians, well, those medals certainly were handsome. And then there was Lewis, of course, the chronic depressive who may have reached his spiritual high point somewhere back along the wild Missouri. In 1809, while on his way to Washington to defend his expense report to a bureaucrat in the War Department, he lay down in a Tennessee inn and shot himself.

Some people are better at leaving than at returning.

But who knew? Not Lewis, not Jefferson, not the Indians. We don’t know either. Particularly since the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, we sense that there’s something enormous and strange ahead of us—in the darkness, over the mountains, through the trees—but we have no idea what it is or how far off. To find it, face it and live to write the story, we’ll have to be resourceful, lucky, patient, flexible and observant, much as Lewis and Clark were. We’ll have to row into the current of our ignorance, one stroke at a time.

With reporting by Deirdre van Dyk