A LEGACY OF MYTH AND CONTRADICTION

While we now realize that Thomas Jefferson was a flawed great man, his words and deeds still offer much to inspire and move us

BY JOSEPH J. ELLIS

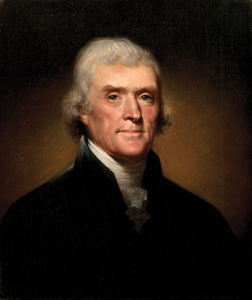

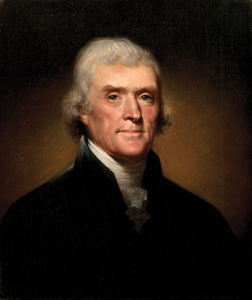

MY EXPOSURE TO THE abiding potency of Thomas Jefferson’s legacy began in Richmond, Va., where I was speaking during a book tour for my biography of Jefferson, American Sphinx. A well-coiffed woman who described herself as a poet got up and proclaimed that everything I was saying about Jefferson was wrong; as she explained in her rich Southern accent, “Mr. Jefferson appeared to me in my bedroom last night and warned me that you would tell lies about him.” She then finished with a flourish: “Mr. Ellis, you are a mere pigeon on the great statue of Thomas Jefferson.” When she came up to get her book signed, I had sufficiently recovered to muster a response: “Madam, it makes no difference whether or not you regard me as a pigeon. But you ought not regard Jefferson as a statue.”

One could argue that all the prominent founders come down to us as statues, mythologized and capitalized as Founding Fathers, creatures of legend more than history. Jefferson’s legacy has certainly benefited from inclusion within this semisacred tradition, though in his case the electromagnetic field is stronger. More always seems at stake. James Parton, one of Jefferson’s earliest biographers, declared that the man from Monticello enjoyed a special aura: “If Jefferson was wrong,” Parton observed, “America is wrong. If America is right, Jefferson was right.” Apparently if American history were a casino, whoever held the Jefferson card could never lose.

The Jefferson Memorial was created by John Russell Pope, the architect who designed the memorial to President Theodore Roosevelt that was planned for the Tidal Basin. Roosevelt’s cousin President Franklin Roosevelt decided not to build it so he could instead erect a monument to Jefferson, a spiritual leader of the Democratic Party

Jefferson’s legacy also possessed the remarkable ability to float from one political camp to another. How else to explain what we might call Jefferson’s disarming political promiscuity? Both Abraham Lincoln and Stephen Douglas claimed that Jefferson was on their side in their famous debates over slavery and sovereignty in 1858. Both North and South went to war believing they fought for Jeffersonian principles. Republican Herbert Hoover and Democrat Franklin Roosevelt insisted both that Jefferson was their political hero in the presidential election of 1932. The beat goes on. Whether it is abortion, gun control, health care or gay rights, partisans on both sides of our most contested issues often identify as disciples of Jefferson.

The historical Jefferson ascended into America’s political version of heaven and was canonized as an all-purpose American saint on April 13, 1943, when President Franklin Roosevelt dedicated the Jefferson Memorial on the Tidal Basin of the National Mall. The real man who walked the earth from 1743 to 1826 was replaced by an incandescent symbol whom Roosevelt called the “Apostle of Freedom.”

Roosevelt’s more urgent purpose was to enlist Jefferson in what he called “a great war for freedom” against America’s totalitarian enemies in World War II. This same juxtaposition of freedom vs. tyranny worked its rarefied magic a few years later to make the Jeffersonian message the sanctioned rationale for the struggle against the Soviet Union in the Cold War.

At the risk of sounding unpatriotic, one could easily puncture the inflated rhetorical balloons that Roosevelt released. Two inconvenient facts come to mind: first, that Roosevelt appropriated [i.e., stole] land on the Tidal Basin already assigned for a memorial to his cousin Theodore, in order to give the Democratic Party a shrine that offset the prominence of the Lincoln Memorial and the great Republican hero; second, that FDR’s New Deal embodied the essence of everything about federal power that Jefferson despised.

But the deeper truth is that not just any man can become America’s Everyman. There were reasons why the Jeffersonian image possessed such infinite malleability; why, if you will, it could float so freely from his age to ours. Jefferson himself seemed to recognize the primal source of his everyman legacy when he chose to place “Author of the Declaration of American Independence” as the first entry on his tombstone.

When the 33-year-old Jefferson sat down in mid-June of 1776 at his portable desk—custom designed for him by a former slave—he was writing what became the magic words of American history. Here they are:

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness—That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.

These have become the most important 55 words in American history, the essence of the American Creed. It was Abraham Lincoln, no less, who first called attention to their abiding significance:

All honor to Jefferson—to the man who in the concrete pressure of a struggle for national independence by a single people, had the coolness, forecast, and capacity to introduce into a merely revolutionary document, an abstract truth ... and so embalm it there, that to-day, and in all coming days, it shall be a rebuke and stumbling-block to the very harbingers of re-appearing tyranny and oppression.

The “abstract truth” was a Jeffersonian version of heaven on earth, where the inherent tension between individual freedom and social equality has been miraculously resolved—think Marx’s version of a classless society after the state withers away—and all men and women can live together in perfect harmony once, to paraphrase an 18th century French philosopher, the last king has been strangled with the entrails of the last priest. It is a glimpse of paradise that is the faith-based source of Jefferson’s enduring allure and the centerpiece of the liberal tradition in American history.

Once folded into the Bill of Rights, Jefferson’s enshrinement of individual rights became an expansive mandate to end slavery, grant women the vote, prohibit racial segregation and in all likelihood sanction gay marriage. Although it is disconcerting to realize that Jefferson himself would have disavowed much of the Jefferson legacy, it is based squarely in the words he wrote and what they have come to mean for us.

While the mythical Jefferson persists with considerable potency in mainstream American culture, his stock has been going down in the scholarly world for several decades. There are two overlapping reasons for the lengthening shadows that have been cast over the Jeffersonian legacy.

In the Black Hills of South Dakota, sculptor Gutzon Borglum blasted from the side of Mount Rushmore a tribute to Presidents Washington, Jefferson, Theodore Roosevelt and Lincoln. Jefferson’s head was dedicated in 1936

First, the ongoing publication of the Jefferson papers, plus the simultaneous appearance of modern editions for all the prominent founders, has created the most comprehensive account of any political elite in recorded history. Because we know more about them, flawed founders have become the new norm, and Jefferson’s flaws have raised serious questions about his place in the pantheon.

The scholarly criticism of Jefferson has on occasion resembled the kind of indictment that Jefferson leveled at George III: he fled in disgrace from his office as governor when British troops invaded Virginia; he claimed to loathe political parties while covertly creating America’s first opposition party; while serving as Secretary of State in the Washington Administration he spread rumors that Washington was senile; he hired scandalmongers to libel his old friend John Adams during the election of 1800, then lied about it; he decried any robust exercise of executive power as monarchical, then took the most far-reaching executive action in American history by purchasing the Louisiana Territory; he bankrupted the New England states with his misguided embargo policy, then left his successor, James Madison, to deal with the War of 1812; he led a lavish lifestyle in which his wine cellar was always well stocked but his bank account always empty, so that when he died, he was the modern equivalent of several million dollars in debt.

The second shadow is slavery. The civil rights movement in the 1960s heightened historians’ interest in race and slavery, and once Jefferson’s life was viewed primarily through that lens, his reputation was fated to fall. Jefferson’s frequent claim that he hated slavery and wished to see it ended also lost credibility given his refusal to play a leadership role in the antislavery movement after 1784, then embracing the patently absurd idea of “diffusion,” the belief that allowing slavery to spread to the Western territories would bring about its demise. If slavery was America’s original sin, and it was, Jefferson’s record of complicity in its continuance and expansion is now a permanent stain on his legacy.

HIS VIEWS ON RACE POSE EVEN greater problems. One of the reasons Jefferson could not envision any workable plan to end slavery was that he presumed, like many of his white peers in both the North and South, that freed slaves would have to be sent elsewhere because the very idea of a biracial American society was unimaginable. In Jefferson’s view, moreover, African Americans were inferior not because they were slaves but because they were black. Nature, not nurture, was the problem, and no effort at education or postemancipation compensation could solve it, because black inferiority was a biologically intractable fact. Asked when a person of mixed-race ancestry could be considered white, he answered that neither a one-half nor a three-quarter white person qualified, but seven-eighths did because “then the blood cleared.”

By this reckoning, Sally Hemings, who was described as “mighty n’ar white,” did not quite cross the line. The story of “Sally and Tom” had its origins in 1802, when a journalist who specialized in scandal, James Callender, broke the news in a Richmond newspaper that Jefferson had fathered several children by his mulatto slave. The accusation haunted Jefferson’s reputation without any resolution about its accuracy until 1998, when new techniques in DNA research produced a perfect match between the Y chromosome in the Jefferson line and in one of the Hemings children. Most scholars now regard a liaison between Jefferson and Hemings as beyond a reasonable doubt.

This titillating tale extended the shadow of hypocrisy and duplicity over Jefferson’s reputation for a serious reason. Namely, the argument that slavery could not be ended for fear that freed slaves would pollute the purity of the Anglo-Saxon race was exposed as an insufferably pathetic contradiction, since Jefferson himself was the father of several mixed-race children.

The net result of the recent scholarship on Jefferson the man has been to complicate the consensus on the Jeffersonian myth. Jefferson has become controversial again, as he was in his own lifetime. But now the controversy reaches an unprecedented level of historical significance and intellectual resonance. For the “Apostle of Freedom” who wrote the magic words of American history is firmly embedded in the racial and racist values that contradict the core meaning of Jeffersonian. If Jefferson’s whole life was a series of contradictions, what does that say about the America he has come to symbolize?

It is safe to ask that question, since Jefferson is securely ensconced on Mount Rushmore, the Tidal Basin, the nickel and the $2 bill. And aficionados of Jefferson’s contributions to architecture, gardening, fine wine, education and table etiquette can confidently pursue their interests without qualms.

For those more disposed to risk exploring the darker side of the Jefferson mystery, let me end with a suggestion: first, read the selections that follow; then go to the Mall, stand between the memorials to Jefferson and Martin Luther King Jr. and read aloud the passage that begins “We hold these truths to be self-evident”; then see if you can start a conversation between the two icons. If you can, it is the newest installment of the ongoing American dialogue. As John Adams muttered on his deathbed in 1826, “Thomas Jefferson still lives.”

Author Joseph J. Ellis’s most recent book is The Quartet: Orchestrating the Second American Revolution, 1783-1789