6

CASEY LEFT, WASHINGTON for a tour of the Middle East CIA stations. He had asked the station chief in Saudi Arabia to arrange for him to attend Catholic mass there on Easter Sunday, and the Saudi intelligence service provided guards. Here was an intelligence service willing to do just about anything, to spread around vast sums of money for intelligence and operations. In Israel, Casey was extremely impressed with the Mossad, which had good human-source intelligence penetrations. Throughout the region he saw a great reliance on human sources. A solid human source was a great advantage, a twenty-four-hour-a-day watch who would provide early warnings. Intelligence services with such sources didn’t have to tune in to precisely the right frequency or communications channel at the right moment, or count on the overhead satellite being in the exact spot. A human source could also provide an evaluation of the information.

When he returned to Washington, Casey decided to concentrate on selecting his DDO, the man who would run the human spies. He found something a little too smooth about the people already in the Operations Directorate. Too much HYP—Harvard, Yale, Princeton. The clothes were too fine, perhaps, the manners too refined, the talk, on the other hand, not sufficiently defined. Not enough-street. They were certainly good and devoted people, but they were too often elliptical. Not enough fire in the belly.

None seemed to have the broad, worldly experience of Casey’s own generation, an understanding of the post-World War II era and business.

Casey had not yet put a name to this description. But Max Hugel, meanwhile, had told him that he wanted more of the action than a Deputy Director for Administration could claim. He had gone so far as to say that someone, whom he did not identify to Casey, had suggested him for DDO. Hugel said he thought he could be of great assistance.

Casey said he would decide soon. He also mentioned the possibility of Hugel to John Bross.

Bross was adamantly opposed. He had been part of the Operations Directorate. Believe me, he told Casey, it’s subterranean. No outsider could fully understand the directorate, let alone lead it.

Bross wanted Casey to have Dick Helms’s views. Helms agreed to come up. He wanted to provide his opinion personally to Casey. Casey told Helms he just knew that Hugel would be good at this. Hugel had learned Japanese and had run a big business in Japan, penetrating the culture and bringing Japanese typewriters and sewing machines here.

Let him punch his ticket as part of the team first, Helms argued. Deputy Director for Administration was important. Why not leave him there for two years and then promote him to DDO? What was the hurry? Helms reminded Casey that in the past the DDOs either had come from the directorate or, in the case of McMahon, had had thirty years at the CIA. Casey ought to be worried about security, Helms said. Not that Hugel was untrustworthy, but he had no background. Security, silence, was second nature to an operations veteran, ingrained, a first commandment. All those secrets in the hands of a neophyte?

Casey thanked Helms, who left thinking that the Director had seen his overwhelming logic.

On the morning of May 11, Casey told John Bross that he was still seriously considering Hugel for the job. Bross continued to oppose it, but he sensed that this was the one matter on which Casey was not going to listen. To push more would be to challenge Casey’s authority. Casey was laying claim to his prerogative.

Later that day, at the meeting with his senior deputies and staff, Casey without prelude, snapping his fingers, waving the issue away, said that Max Hugel was being appointed the new DDO.

There were about fourteen people jammed into the conference room. Normally, there was no way whatsoever to read anyone at one of these open meetings. But this time the silence was stunning; a growling stomach would have been heard. The CIA people had just barely accommodated themselves to Hugel as the DDA.

There was not a word uttered. What was there to say? And Casey had not invited comment. One beat and he moved on to the next subject.

A joke already in circulation was, “What does Hugel say each morning to Casey? ‘Boss, Boss—the plane, the plane!’” Just like the doting, white-suited midget Tatoo in the television show Fantasy Island announcing a new batch of visitors to Ricardo Montalban.

After the meeting, word spread throughout Langley: Casey has made a typewriter-and-sewing-machine salesman the DDO.

In his second day on the job, Hugel called together his senior assistants in the DDO. He had written out his main points. He pledged to work for the directorate, to build it, to support it. He told them that they were underpaid and that things should be done to rectify that, reminding them that many of their colleagues had left because they couldn’t afford to send their children to expensive colleges.

The experienced hands knew that this was an idle promise. Government pay is set in stone by Congress and little can be done about it, especially by an agency deputy.

Hugel said that people should advance only on merit, and that the younger people should be given a chance. They needed more language training, better human intelligence, more effective counterintelligence.

When he finished, there was no reaction—nothing. Hugel looked around the room. All these people had been trained to conceal their purposes, their feelings. There wasn’t a single clue on a single face. Hey, Hugel wondered to himself, have I said something wrong? But these people considered inexpressiveness an art.

Hugel met the challenge with more work. He was given a code name, a secure phone, a car, a driver, and a home safe in which to store secret documents. As he scanned the secret-agent reports and the outlines of some of the operations, it was clear that much of the secret information came from people who were betraying their countries. He was uneasy. Why were these people selling out? Was their information reliable?

Hugel paid a courtesy call on Senator Goldwater. The Senate Intelligence Committee chairman was a key base that needed covering. When Hugel came in, it was obvious that Goldwater didn’t know him from beans. Goldwater sat, asked no questions, said almost nothing.

Hugel left feeling ice. There had been no advance preparation by the CIA liaison with the Congress. Hugel’s way had not been greased.

On May 15, four days after his appointment, Hugel picked up The Washington Star, which carried a regular column by Cord Meyer, who had been with the CIA for twenty-six years. Passionately anti-Communist, pro-CIA, and a friend of John Bross, Meyer, a Yale graduate who had lost an eye in combat during World War II, was the embodiment of the Ivy League Cold Warrior. Class. Tweed. Connections. He had risen to be the No. 2 in the Operations Directorate before leaving the agency in 1977. As a columnist for the Star he reflected old-boy thinking and had instant access to its latticework, fed daily by phone calls and lunches of retirees who seemed never to leave town.

Hugel read the headline of Meyer’s column in astonishment: “Casey Picks Amateur for Most Sensitive CIA Job.”

“…Casey has rejected the unanimous advice of old intelligence hands,” Hugel read of his own appointment as DDO. “This government job was once described by columnist Stewart Alsop with only slight exaggeration as ‘the most difficult and dangerous after the president’s.’

“Allen Dulles, Richard Helms and William Colby all held this job before subsequently becoming CIA directors but they earned their promotion by many years in intelligence assignments.

“The KGB chiefs in Moscow will find it incredible….”

Meyer noted that the only other case where a CIA director had reached outside for his DDO had been the appointment of Richard Bissell, a brilliant economist who as DDO “became the unfortunate architect of the Bay of Pigs.” The Hugel appointment, he wrote, was “a breathtaking gamble for which the country will have to pay heavily if Casey has guessed wrong.”

Hugel was deeply hurt. Meyer had not called to hear his side.

The next day Hugel glanced at The Washington Post. “Daggers Drawn for New CIA ‘Spymaster,’” said the front-page headline. The old boys were coming out into the open. George A. Carver, another CIA veteran from Yale, was quoted: “This is like putting a guy who has never been to sea in as Chief of Naval Operations…. It’s like putting a guy who is not an M.D. in charge of the cardiovascular unit of a major hospital.”

Casey was quoted defending Hugel, saying that the criticism was coming from “a bunch of guys who think you can only understand this business if you’ve been here 25 years.”

The New York Times editorialized against Hugel’s appointment, under the sly headline “The Company Mr. Casey Keeps.”

Casey and Hugel discussed the matter and agreed that things were going well, not badly. They were challenging the status quo, and the status quo didn’t like it. Casey dashed off a letter to the Times that was published May 24, praising Hugel’s “drive, clarity of mind and executive ability…abilities and experience.”

Reading the articles at home, where he was beginning a new career as a writer, Stan Turner understood the old-boy attack. It brought back a rush of disagreeable memories. Turner felt a kinship with Casey, who was obviously getting the full treatment. As a gesture of support, he wrote a letter to the Post, published on May 25:

“Mr. Casey is ultimately responsible for how well the directorate performs. He is entitled to select his own team and should be judged on the results, not the appointment.

“I received similar criticism in 1977 when I made changes and reductions in the Directorate of Operations. These proved to be eminently successful. Let’s give Director Casey his chance without the burden of premature criticism.”

At the White House, Meese, Baker and Deaver were uneasy about all the attention that was focused on Casey’s man Hugel. Sensitive intelligence work was under way, and if Hugel was a fuck-up there could be problems for Reagan. Their protective instincts were running high. They had always been skeptical about the value of Casey’s and Hugel’s operational work during the presidential campaign. Were clowns running the CIA?

Casey wrote a private letter to the President arguing that Hugel possessed valuable business skills, hinting that Hugel’s efforts in organizing special-interest groups, especially ethnic voter groups, were not all that different from covert work.

The Reagan aides decided there was no way, and no good reason, to intervene.

Casey first noticed the cool eyes, though the man was six foot eight.

“Mr. President, we have been on the defensive ideologically,” the man said in a booming, confident voice. He continued with a well-crafted paragraph about El Salvador. The junta, backed by the United States, was hard to defend; the human-rights violations were too frequent, too visible, though Duarte was doing his best. The Administration must return to the offensive, and not just with a military program and a diplomatic program. The Reagan Administration must work for free elections in El Salvador, he said. Even though the Special National Intelligence Estimate just issued that month, June, by Director Casey had concluded that there was a military stalemate between the Salvadorian junta and the rebels, and that it would be two years before the junta could gain a clear upper hand, democracy must be the goal.

Casey saw President Reagan perk up, stir in his chair. A real nerve had been struck. It was a simple idea, and certainly far in the future.

“Let’s go with that,” the President said.

Casey had been impressed with the presentation made by Thomas O. Enders, the Assistant Secretary of State for Latin America. In several months, Enders had taken charge of Administration diplomacy and policy for his region with flair and drive. He had a seasoned understanding of interagency infighting as State, Defense, Casey’s CIA and the National Security Council fought for control. By tradition, he chaired the meetings of the normally contentious representatives, which he called the “core group.” Some weeks they met daily, even twice a day. Enders knew he needed consensus, and intellectually he was attempting to develop a coherent plan. Casey knew Enders from his own SEC and State Department days. There was no more perfect product of the Eastern seaboard than Enders: parents, Ostrom Enders and Alice Dudley Talcott, of Connecticut; Yale ’53, graduating first in his class. When he was appointed assistant secretary, Enders didn’t know Spanish, but he was a brilliant linguist and learned it in several months. He had an affected manner and was intellectually impatient, try as he might to conceal it. He was suspect by both left and right; by the left for his role during the Vietnam War in the U.S. Embassy in Cambodia, carrying out the “request-validate-execute procedure” for the heavy bomber attacks; by the right because he had been a Kissinger protégé.

Casey made sure he sat down with Enders later to pick his mind.

“There is no structure for decision-making in the White House,” Enders lamented. His boss, Haig, had tried preemptively to take full control and had lost. “But no one won.”

Casey took note.

“But I can make the interagency core group work,” Enders said.

Casey pledged that the CIA would cooperate—no turf battles from him. But he wondered whether the thinking was large enough. The set of concepts—free elections and democracy—for El Salvador was just a start. The Administration needed a plan for all of Latin America; in fact, one was needed for the whole world.

Enders agreed. The splintering of foreign-policy authority was going to make things difficult. “Al came in with a cry of alarm but no plan.”

Casey dipped into the CIA institutional memory some more—the files, briefings. He probed the key CIA people, frequently jotting on small index cards. World history in the last six years had been dominated by one conspicuous trend: the Soviets had won new influence, sometimes predominant influence, in nine countries:

South Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos in Southeast Asia.

Angola, Mozambique and Ethiopia in Africa.

South Yemen and Afghanistan in the Middle East and South Asia.

Nicaragua.

How had this been done? It was clear to Casey that the Soviets, exploiting the aftermath of the U.S. withdrawal from Vietnam, had used surrogates and proxies to stage revolutions and takeovers. Was there a way to do it to the Communists? Not just a piecemeal approach, such as seizing on the Afghanistan invasion to support the rebels there; or acceding to the requests of Saudi Arabia to help covertly in South Yemen, or promoting democracy in El Salvador and creating a firewall against the leftist rebels.

In the same six-year period the Soviets had lost considerable influence in six countries—Bangladesh, Guinea, India, Somalia, Iraq and the Congo. But this was ambiguous as far as Casey was concerned. He was interested in taking one back from the Soviets—a visible, clean victory.

“Where can we get a rollback?” Haig had asked.

“I want to win one,” the President had said.

Casey realized that this meant guerrilla warfare. He had reinforced his education in the importance of guerrilla movements five years earlier while researching his book on the American Revolutionary War. Published in 1976, for the Bicentennial, the 344-page book, Where and How the War Was Fought, was the result of the Casey method—extensive reading and on-scene inspection. He had immersed himself in the main books on the Revolutionary War. He had sailed through the key volumes of Douglas Southall Freeman’s seven-volume George Washington; Casey would say that Volumes 3 and 6 were indispensable. A speed reader, he raced through many pages a minute, grasping concepts and point of view, lingering where he wanted, skimming where he lost interest. Friends considered him a book thief who would borrow and rarely remember to return. The books became precarious stacks at Mayknoll. The literature on Revolutionary intelligence operations, deception and political warfare sparked particular attention, including Pennypacker’s General Washington’s Spies, Ford’s A Peculiar Service and Carl Van Doren’s The Secret History of the American Revolution.

The real joy in his research had been a string of weekend field trips with Sophia and Bernadette. Casey loved traveling with his wife and daughter. It was a comfortable trio. One Thursday they all took a night flight to Maine and for four days they followed the route of Benedict Arnold along the rivers to Quebec, then along the St. Lawrence to Montreal, and the Richelieu to Lake Champlain. A three-day weekend was spent following General Washington’s trail from Valley Forge across the Delaware into New Jersey battle sites. They did Boston, Philadelphia, New York, the Carolinas, Georgia. On a cruise they retraced the route from Annapolis to Yorktown down Chesapeake Bay. Casey had his notes, his books, photocopies of the relevant maps, Boatner’s Landmarks of the American Revolution. He went to the hilltops, walked the trails, carefully eyed the relics. Sophia and Bernadette followed each step.

“I found the most vivid and immediate sense of being there, actually seeing the tactical and strategic significance along the Arnold trail…” he wrote. Each time he wanted to go to the exact spot and unravel the Revolutionary geography as it was then, often hidden under modern cities and pavement.

On the excursions, or as he waded through the books, Casey asked the central question: How and why did the Americans win? How had such a ragtag group been able to defeat the foremost world power, the British? The Revolutionaries, he finally wrote, were victorious because they used “irregular, partisan guerrilla warfare.” They were the Vietcong, the rebels in Afghanistan. The spirit, the techniques, the tactics were with the irregulars. You really had to appreciate a native resistance, he said. It was the side to be on. This was, Casey felt, a point of continuity between the eighteenth and twentieth centuries. Now he could apply it. If the native resistance did not come banging on the door of the CIA, as the Afghans had done, then maybe the CIA had to go out and discover it.

To further avoid surprises, Casey began looking for another outsider. He wanted someone to act as an intellectual tripwire to alert him to looming foreign disasters, perhaps someone on the analytic side to mix it up with the CIA insiders. There was just too much wooly thinking. He invited up to his office Dr. Constantine C. Menges, a tall, bespectacled, scholarly looking forty-one-year-old Hudson Institute conservative who had worked on the Reagan campaign. Menges had a radio announcer’s voice and spoke with eternal self-confidence. When Casey questioned him about major foreign-policy problems, Menges presented to him copies of several short op-ed pieces he had written for The New York Times. In a 1980 article, Menges stated that events in Iran, Afghanistan and Nicaragua marked “a turning point in the invisible war between radical and moderate forces” for control of oil, the Middle East and Central America. In another, “Democracy for Latins,” he called for a strategy to defeat the Soviets in Latin America by promoting democracy and the center; ties and support to right-wing dictatorships alone would not work, he said. In still another, “Mexico: The Iran Next Door,” Menges forecast trouble to the south.

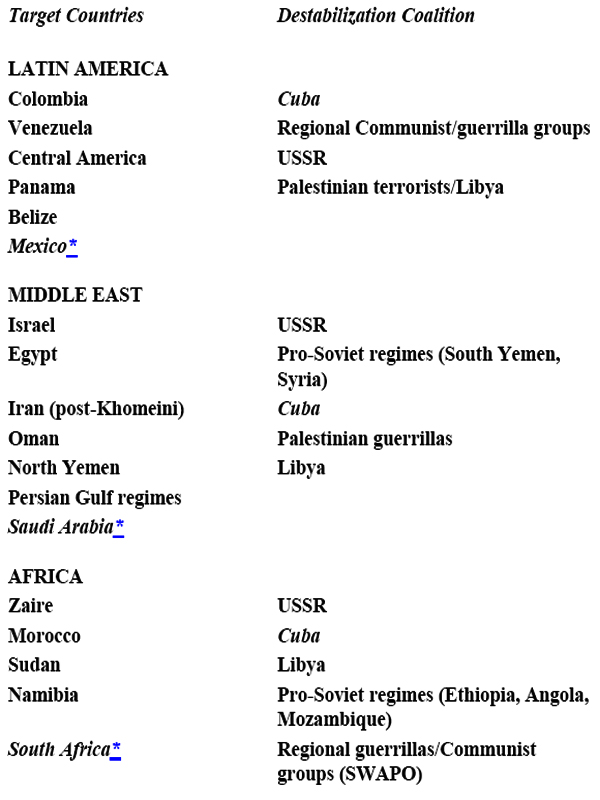

Casey glanced at the articles, which seemed to show strategic thinking, relating events taking place in different parts of the world, and as well a willingness to give weight to ideas. Menges had developed a rational calculus about Communist expansion. He brought a two-page paper in which he described how the Communists joined in partnership with others in what he called the “Destabilization Coalition.”

Included was a chart for three strategic areas:

POLITICAL-PARAMILITARY WAR AGAINST

U.S. INTERESTS IN THREE STRATEGIC ARENAS

These were overall strategic objectives and techniques, but Menges said the Communists had no timetable. They were patient.

Casey later read the articles and asked Menges back for a second meeting, during which he invited him to be candid. Menges said he was worried about the competence of the whole CIA, which, like any bureaucracy, avoided accountability and responsibility. Back in the 1970s he had been a deputy assistant secretary for education and had worked for Frank Carlucci, then the deputy at Health, Education and Welfare. When Carlucci had moved to become deputy CIA director in 1978, Menges had warned him about trouble in Iran. No one had listened. In 1979, before the Sandinista revolution, he had forecast leftist trouble in Nicaragua. Again he had gone to Carlucci and the CIA, where his views were ignored. This was not hindsight. He produced more of his published articles, including one, “Echoes of Cuba in Nicaragua,” in June 1979, before the Sandinistas overthrew Somoza. It forecast that the Sandinistas would pose as moderates and use “coalition government” before revealing their true Marxist-Leninist colors.

“Success,” the article said, “would create the political base and momentum for beginning revolutionary warfare against Mexico during the early 1980s.” Menges told Casey that what disturbed him was not so much the way his ideas had been treated as it was the smug failure of the CIA to anticipate and prevent crisis.

Casey offered Menges the job as his national intelligence officer for Latin America. For that region he would represent the DCI in the inter-agency meetings, oversee the writing of the National Intelligence Estimates, head a monthly “warning” meeting on potential threats, and recommend the U.S. response.

Menges was reluctant to join the CIA. He said it might taint his academic work.

“Look,” Casey said, “you’re so concerned about this, and here you were warning the Carter Administration for three years about Iran and Nicaragua, and now I’m asking you to come and serve…. What are you waiting for?”

Menges accepted.

Casey was surprised that the agency provided regular background press briefings to reporters heading overseas on assignment. He told Herb Hetu, Turner’s public-affairs man who was still at the CIA, to discontinue all such briefings at once. Hetu thought the briefings provided important media contacts and began to protest, “But—”

“I didn’t ask for discussion or debate,” Casey said. “Do it.”

One evening in early July, CIA general counsel Sporkin received a strange, muffled call at home. The caller finally identified himself as “Max,” and requested an urgent meeting “at the place.” Sporkin realized it was Hugel, who wanted to talk at headquarters. When the two met within the hour, Hugel said that he needed help. Two former business associates from New York, securities dealers Thomas R. McNeil and his brother Samuel F. McNell, were making some accusations that they had secretly taped Hugel giving out insider information on his company Brother International six or seven years before.

On Friday, July 10, Sporkin called the Post. Another reporter, Patrick Tyler, and I had received copies of sixteen Hugel tapes the previous month, and we were pursuing a possible story. Sporkin said he wanted to hear the tapes. We said it was premature. Sporkin offered to help, adding that if anyone in the CIA had done anything wrong, he and Casey had to know. Finally, we agreed that Sporkin could come and listen to the tapes if he brought along Hugel, whom we wanted to interview. Sporkin insisted on coming that afternoon. Casey wanted to know now.

Several hours later, more than a dozen people assembled around the table in the board room on the eighth floor of The Washington Post: Sporkin; Hugel, with several of his personal attorneys, including Judah Best, a Washington lawyer who had represented Vice-President Spiro Agnew; Benjamin C. Bradlee, executive editor of the Post; Tyler; myself; two attorneys for the Post who were securities experts; and four other Post editors.

Hugel, five foot five, wore a conservative chocolate-brown pinstriped suit, a plain tie and a shirt with small light, subdued dots. His smile was warm.

“I’m here to find out what the hell’s going on,” Sporkin said, adding that he represented only the CIA and not Hugel personally. He then slouched back in his chair and looked bored.

We tried some general questions. Had Hugel ever provided inside information to the McNells? Had he ever threatened to kill one of the McNells’ lawyers? Did he know that money he had loaned one of the McNells had been intended to go into their securities firm, which had been pushing the stock in Hugel’s company?

Though his lawyers intermittently protested, they let Hugel answer before any tapes were played. “Untrue, completely one hundred percent untrue” that he knew the loan was going to the securities firm. He denied everything. “The answer is absolutely, unequivocally no—absolutely not. Never.” He nervously rubbed his large, chubby hands together. His voice had a sweet quality as he made a plea and began to refer to those in the room by their first names. Yes, he wanted his stock to go up, of course he wanted his stock to go up. “If a guy’s taping you on the other side of the phone,” he said, looking for understanding across the table, “I don’t know how he’s wording the question or what he’s saying. If you don’t know you’re being taped”—and he looked up—“you can set everybody up.

“That’s an unfair thing,” Hugel added.

Sporkin interrupted. “I don’t care if I stay here all night, but if you’ve got the stuff on the tape I must have it. I’m just telling you I’m going to be here until hell freezes over and I want to hear that. I’ve got to make recommendations.

“Those are very serious charges,” Sporkin said. “I mean some of them are. Some of them, I think from my [SEC] background, are just bullshit, quite frankly. But some of them when you’re talking about market manipulation, it’s a very”—and he thumped the table loudly—“serious charge. And if you’ve got the proof on that, I’ve obviously got to see it.”

Tyler played a December 13, 1974, tape of a conversation that had taken place after the McNells’ lawyer threatened Hugel with a lawsuit. Hugel’s voice came through loud and clear: “And then he had the audacity, the nerve, to threaten me with some goddamn cockamamie lawsuit, that I—it’s so distasteful to me that I’m ready to throw up…. What the fuck kind of shit is that?…Let the fuck sue me…That’s bullshit, Sam, I’ve been at that cocksucker, I’ll put that bastard in jail…. I’ll kill that bastard.”

Tyler clicked off the recorder.

“What’s there to comment on?” Hugel said sheepishly. “It is what it is.”

“That’s your voice? Do you recall the conversation?”

“Yes,” he said.

“But you indicated earlier that…”

“Obviously my memory failed me,” Hugel said stiffly, bravely facing the contradiction. In pain, he said again, “The tape is what it is.” And he asked to hear the next tape.

We played a tape in which Hugel told Tom McNell, “Get some pencil and paper, will you? What I’m giving you is strictly confidential stuff, okay?”

It was a long tape, again clear and precise, in which Hugel provided the dollar figures on sales forecasts.

Is that insider information?

“I can’t answer that question. I will not answer…”

Hugel hesitated. More tapes were played. What about the insider information?

“You know, you take me back into ’74, and the only reason I could possibly do it is like any aggressive businessman that’s complimenting his company and saying things are happening, but, you know, and you’re proud of what you’re doing, that’s the only possible reason. I’m a very enthusiastic guy, I could…”

But if you’re proud of what you’re doing, you wouldn’t want to keep it confidential?

“Well, I said ‘confidential,’ you know, that’s what the tape says…. Ah hell, it’s a way of…Jesus it’s…Why would the man tape my conversation?” Hugel was almost inconsolable on this point. “Why?” he asked, looking around the room. “What does it, what’s the purpose?”

Sporkin, still wearing his hat as the foremost securities enforcement expert in the country, said that the missing element in all this was evidence that Hugel had profited from his disclosures of the information. That was the necessary element to make it a crime, he said.

“I guarantee you,” Sporkin said, “that there’s none of us sitting at this table that hasn’t said something on a phone that if it had been taped we would not be very happy with it.” There were nods all around.

Sporkin asked Hugel and his personal attorneys to leave the room. After they left, Sporkin said in almost a whisper, “This is going to be a very difficult decision on my part…. You know, I can make an easy decision. There’s an easy decision I can make.”

“Cut,” Bradlee said.

“Yeah,” Sporkin said. “Whether it’s a correct one I don’t know.” He wanted to listen to all the tapes in full and make an assessment for Casey.

“It’s not our job to help you make your decision, that’s the short of it,” Bradlee said, but Hugel, of course, would be provided a chance to respond to anything before it went into the paper.

“I don’t know whether you have a smoking gun there or not,” Sporkin said.

Hugel returned to the room, saying he was postponing a trip abroad as DDO on an important operation.

“This is a very serious matter, my friends,” he said. “My personal reputation’s at stake. I intend to see this thing through to its very end.”

Midafternoon Sunday, July 12, Casey returned from a three-day trip abroad and convened a 4 P.M. meeting at Langley attended by Inman, Sporkin and Bob Gates. The information was still fragmentary, Sporkin told the others, saying that it was not clear whether there were possible violations or stock manipulation.

Inman told Casey that when a problem like this arose there were two overriding considerations. First, there could be no cover-up or appearance of a cover-up. Second, the potential problem had to be isolated. That meant Hugel should go on administrative leave. If there wasn’t anything to it, he could then come back. If there was something, he was effectively out the door.

Sporkin said he was opposed to administrative leave. What event in the future would change the situation? Who would decide there was nothing to it? These things could hang fire for months or more.

Casey, too, was reluctant to agree to administrative leave. It might be terribly unfair. These things often came to nothing—headline charges that are investigated and lead nowhere. And in the meantime someone’s career and name were muddied. Casey wanted to know what was the worst aspect of the whole matter.

Sporkin said it was the tapes—the language and the calls with advance information.

Casey felt that chief executive officers call their stockbrokers, call them all the time.

It is going to be a problem, Sporkin said, having the DDO quoted on tape saying some pretty rough things. On one tape, for instance, Hugel told his stockbroker, “I’ll cut your balls off…. I’ll get my Korean gang after you and you don’t look so good when you’re hanging by the balls anyway.”

Sporkin decided he had an obligation to be frank with Hugel—in private. “Look, Max,” Sporkin said later when the two were alone, “the statute of limitations has run. So no one can prosecute you. But you have to go.”

Why? Hugel asked.

“Quit,” Sporkin said. “You go to the Hill to testify and they’ll eat you alive.” The problem, Sporkin explained, was perjury, certainly unintentional. You could go pitch out your categorical denials, but you can’t argue with those tape recordings. Congress is not some newspaper where you can say anything, deny anything. “You want only one story to come out after the one on those tapes,” Sporkin said. “That’s the one on your resignation—then the Hill will leave you alone. You’ll be history. That’s my advice. You asked for my advice as a lawyer, as a friend. That’s it. It’s in the interest of the agency and in your interest, so I can say it to both you and the Director.”

That evening Hugel invited both Casey and Sporkin over to his house for dinner. Hugel felt a strong personal obligation to Casey for the DDO job in the face of all the internal opposition. He was deeply aware of the trouble his appointment had already caused. Among the three CIA newcomers who were gathered around Hugel’s table there was less than a year of CIA experience. Hugel said that the charges were a bloody lie.

In the presence of Casey, Sporkin hovered in a neutral position.

Casey mentioned that Inman had suggested administrative leave for Hugel, an indefinite leave until the matter was cleared up.

“Bill,” Hugel said, “there is no way that I came to Washington to get myself clobbered in the face every day.” In an office as visible as the DDO, he didn’t see how he could win a battle to clear his name and do his job. His hands would be tied. “I can’t win that battle as a public servant. The only way I can win it is as a private citizen.”

Sporkin said he was sure that the newspaper story would be published soon.

Hugel told Casey, “If the article is detrimental to the agency, to myself, to you, I’m going to resign.”

Casey wasn’t sure. Administrative leave was not a great solution, but it was looking better than resignation.

“If they come up with an article that’s damaging,” Hugel said, “I’m not going to hurt the agency. I’m not going to hurt you. And I’m certainly not going to hurt the President. I’ll resign.”

“Look, Max,” Casey said, “it’s your shot to call.”

The next morning Hugel’s lawyer, Judah Best, called the Post and said they wanted a second meeting. Best brought sixteen documents from Hugel’s business files and a letter saying that they needed additional time to gather more information. A story now would be “reckless,” he said.

That afternoon the same group gathered in the fifth-floor news conference room. Hugel seemed subdued and even more nervous. We said we wanted to avoid a repeat of Friday’s meeting when he had issued blanket denials about certain actions and then was faced with the contradictions on tape.

Hugel began to protest.

Sporkin said to him, “Listen to his question and if you don’t know, why don’t you just say you don’t know. That’s what’s not helping you. If you don’t know, say you don’t know.”

We said we planned to run a story the next day and it would include any statement from Hugel.

“I want to make my request,” Sporkin said impatiently. “Fairness or whatever it is, I still want to hear those tapes.”

More were played. Twice Hugel excused himself to go to the bathroom. He finally asked for the floor.

“I want to apologize for my very quick answers on Friday to your questions,” he said, “without having the chance to think through…. My responses could have been much better. I had no intention to give deceiving or misleading statements.” He was wringing his hands and leaning forward. He said he had never profited from those stock transactions. He might have been a novice; he might have been naive. But he had started a company from almost nothing and left it when it was doing $100 million a year in business. His net worth was $7 million.

Hugel paused. He said that in a 1957 book called Operation Success there was a chapter devoted entirely to his success in business with Brother International.* “I was on the front cover of Coronet magazine, and we’re trying to get a copy and will send it to you…So I was proud of what I did and I’m proud of it now.”

He listed his qualifications, his fluency in Japanese, his international experience, his ability to deal with foreigners.

“I took this job because I wanted to serve my country. I did it at great financial sacrifice. My whole life and reputation is at stake here,” he said. Tears were welling in his eyes. “That it would be most damaging to me and my family…Who are perfectly innocent. And should not be treated that way. And it’s a shame,” he said, raising his voice dramatically, the Hugel of the tapes, “that an individual willing to give up all kinds of potential monetary gain just to come and serve this country, just to try to do that, should be condemned by people of this type on information that goes back well over seven or eight years…”

Hugel said it would be “most difficult in the future to get people to come to Washington to accept jobs.

“I’m just giving you gut, heart.”

At CIA headquarters, Casey was growing increasingly anxious that he had not heard from Sporkin. He figured he had better advise the chairmen of the congressional intelligence committees. Casey reached Edward P. Boland of the House committee, but was unable to get through to Goldwater.

Later Hugel’s attorney issued a three-paragraph statement emphatically denying any wrongdoing, and saying he was “deeply disappointed” that the story was going to be published. Hugel added, “I shall continue to serve my country as long as it requires my services, and long after these rantings from the past have ceased.”

Hugel thought it must be about 3 A.M. when he was awakened by Sporkin’s call. The story was out, Sporkin said, reading the headline, “CIA Spymaster Is Accused of Improper Stock Practices,” and continuing: “‘Max Hugel, who holds one of the most sensitive jobs in the Reagan Administration as chief of the CIA’s clandestine service, engaged in a pattern of improper or illegal stock market practices…’”

“That’s disgusting,” Hugel said.

Sporkin read on, outlining the allegations, saying that there were extensive quotes from the tapes.

“Okay,” Hugel said. “That’s it. Don’t read me any more. I’m resigning.”

Soon after sunrise, Hugel called Casey. “I’m done,” he said emotionally. “I’m doing it. I’m resigning.”

Casey said it was unfair—totally unfair.

Hugel, choking up, agreed.

Casey didn’t try to change Hugel’s mind.

It wasn’t until 9:40 A.M. that Casey reached Goldwater to tell him what the Senator already had read in the newspaper. Goldwater was angry. Why was the DCI so late with the news? He had heard a reliable rumor several days earlier that the story was coming.

In the White House, chief of staff James Baker and counsel Fred Fielding were worried. They wanted the damage limited at once. Fielding was pushing hard for an immediate resignation and had made the point directly to Casey. Baker called Casey.

“Max is going to step aside,” Casey said.

Baker was surprised and relieved that it had moved so fast. When Baker told the President later that morning, Reagan too was quite surprised, remarking that he was not sure what Hugel had done wrong.

At his home, Hugel read the article for himself. There was his picture on the front page. Jesus, Hugel thought, it was a lousy picture. He had so many better ones.

There were columns of transcripts from the tapes with all his bare language concealed as if it was not fit for the Post. Fuck was “f—-.” Shit was “s—-.” Cocksucker was “c—-sucker.” Piss was “p—-” But nothing was left out. All very clever, dirty and crude, Hugel felt.

He dressed, and his driver took him to CIA headquarters. It was painful in the corridors as he walked to his office. All eyes were on him. Some people seemed to be crying. Some came up to him and said how unfortunate, how unfair. Some couldn’t say what was on their minds. Hugel was sure that many were elated: the outsider was out. And there was a coldness in others, the professional chill.

He wrote a “Dear Bill” letter which he walked down to Casey’s office. Both Hugel and Casey were very emotional. It was a most difficult parting.

Casey’s letter accepted the resignation “with deepest regret.”

Hugel went back to his office, picked up his briefcase and walked out.*

For the moment Casey had had enough of bucking the system in the Operations Directorate, and he immediately named John H. Stein, forty-eight, the new DDO. A Yale graduate with a twenty-year career in the agency, including assignments as CIA station chief in Cambodia and Libya in the seventies, Stein was low-key, hard-working, and not a wave-maker.

It was time, Casey concluded, to settle down the Operations Directorate. In practical terms, he would just have to be his own DDO.

Casey decided he would have to set an example. For some time, one of his Middle East stations had been talking about placing an eavesdropping device in the office of one of the senior officials in that country, a main figure whose conversations would provide vital hard intelligence. At the station it was back and forth about the risk assessment; there was hesitancy and floundering as the DO officers debated how to make an entry into the office. They had raised irresolution to an art form. “I’ll do it myself, god-damm it,” Casey said. Though it was totally against tradecraft practice to risk using even a DO officer for such a mission, the DCI, insisting, placed the bug during a courtesy visit to the official—another violation of trade-craft. By one account, he inserted a thin, miniaturized, long-stemmed microphone and transmitting device shaped like a large needle in a sofa cushion during his visit. By another account the listening device was built, Trojan-horse style, into the binding of a book that Casey brought as a gift for the official. One senior agency officer insisted that the story was apocryphal, but others said it was true. Among several DO officers it was accepted as gospel. Casey only smiled when I asked about this incident several years later. But he glowered dramatically when I mentioned the name of the country and the official, and said that that should never, never be repeated or published.