Tasmania

––––––––

Wheel skids, car fridge, swag, tarp, computer gear, phone chargers, cable ties, satellite phone, CB radio, engine oil, tool kit, diesel cans x 2, ratchet straps x 2, snatch strap, tyre pump, rope, knives, rifles, ammo and case (lockable), clay thrower and clays, fishing rod and tackle, torch and charger, drone, soap, first aid kit – check.

Day 1

––––––

Packing

Tent, sleeping mat and sleeping bag, chairs (folding) x 2, water bottles x 3, wetsuit, rain jacket. Fire-lighters, small grill, tongs, gas cooker, jaffle iron, plastic tub, whisk, bowls x 2, tea towels, cups, plates, cutlery, coffee, beer, salt, oil, snacks.

What else? I’m sure we’re missing shit...

It’s about 11pm on a Saturday in late September, and I’m in Bowral with Cameron Cansdell. A fellow chef and lover of the outdoors, Cam has a restaurant called Bombini, at Avoca Beach on the NSW Central Coast, and he was the chef at my wedding. Over the years we’ve become good mates and he’s coming along for the initial leg of the trip, so he’s helping me pack. I collected the car from Land Rover head office in Sydney earlier that day, and we’re going through everything in detail, over and over.

The whole trip will cover 13,000 kilometres and, along with photographer Adam Gibson, I will essentially be living out of this vehicle for a couple of months. We have our swags and tents, but I have no idea where we’ll be sleeping each night, and I’m happy for it to be ad hoc – a quiet corner of somebody’s property, a nature strip or roadside campsite.

We have a massive YETI Tundra cooler to fit in, as well as a fridge. We’re struggling to squeeze it all in, so we decide to strap as much on to the roof as possible... At midnight we’re still going – I just want to get this finished. We need to be up early for the seven-hour drive to Port Melbourne, where we’ll board the Spirit of Tasmania ferry to Devonport. It’s 1am before we hit the sack. I’m ruined and tired, but I can’t sleep, can’t stop worrying if we’ve got everything covered, plus I’m bloody excited.

Day 2

––––––

Across Bass Strait: Spirit of Tasmania

Our day starts at about 6am. Both Cam and I are pumped and we fly down the Hume Highway, stopping in a field of vibrant yellow canola near Gundagai to water the plants and stretch the legs. We reach Port Melbourne three hours ahead of boarding time, but Cam and I soon realise we have an issue: we have no way of brewing coffee on the road. All we need is something small that can go on the fire or stove. Cam’s going through Google and directing me around the city centre – it’s ironic that our first foray into hunting and gathering is in Target for a coffee maker.

Back at Port Melbourne, we need to line up early because we have a small arsenal in the car: a Remington 243 rifle, with rounds of ammo, and a 12g lever-action shotgun. One is for the fallow deer we hope to hunt and eat along the way, the other is for wild ducks and waterfowl. They do an inspection and insist that everything on the roof needs to be packed inside the vehicle... Once this is done, a bloke takes the ammo and rifles and locks them away in a cage. The quarantine guys actually seemed more concerned about the fruit we had in the car than the guns – this is Tassie, though!

When we finally get to drive on board, I get a message from Dave Moyle wanting to know if I’m in Tassie yet. Having lived and worked there for several years, Dave has helped me set up some amazing places to visit in the island state, and he’s going to meet us in a few days’ time on Flinders Island. ‘Just boarding,’ I tell him. ‘Have fun on the ship, it’s like a floating RSL,’ he replies. He’s right, this thing is massive. We park on the car deck and head upstairs. I’m thinking maybe an epic schnitty and, as for Cam, deep down I know he wants their finest sauv blanc by the glass (sorry, Cam). Instead we find microwaved pizzas (in fucking plastic). It’s crook – and no, we don’t eat. We settle for a beer and go to bed hungry.

Day 3

––––––

The northwest tip of the island:

beef and octopus

We dock early next morning, by which time I’m ready to eat a body part. Cam jumps on to Google again and finds a little joint in downtown Devonport called Fundamental Espresso. The fact that espresso is spelt properly seems like a positive sign, so we drive straight there, to find unreal vinyl playing in the background. After a night on the Spirit of Tassie with its frozen pizzas, we need a dose of culture and good coffee. And by the look of their bagel menu, we’re in for a tasty little treat – bloody epic bagels, I had two!

I text Adam, who is driving up from Hobart, to meet us here. He arrives with heaps of shit and camera gear, including a swag that could sleep about ten, so we spend the next half-hour working out how we’re going to fit it all into the Land Rover.

It’s mid-morning by the time we make our way towards Stanley, in the northwestern tip of the island, to meet a farming family whose passion for life and nature inspires me. The fresh sea air, clean water and high-quality pasture in this part of Tasmania produces some of the best beef I’ve tasted in Australia. The Cape Grim peninsula first came to the attention of European settlers as early as 1798, during Bass and Flinders’ circumnavigation of Tasmania. As most of this part of the island was heavily forested, the pasture here offered precious grazing land for settlers’ sheep and cattle.

The Bruces began farming here in 1975, when David and Marie Bruce bought the Western Plains property, followed by Highfield in 1980. Four adjoining properties have since been added to their holding: The Oaks and Harman’s Swamp in 1985, Morton’s in 1996, and Glas Inis in 2013. The Bruces practise rotational grazing to ensure the cattle have access to clean fresh pasture every 2–4 days. John, David and Marie’s son, explains that the exact timing of the rotations is determined by the leaf-emergence rate of the ryegrass, which is indicative of the strength of the rootstock. This varies across the year, depending on soil temperature and rainfall.

Talking deer heads and white walls with Iain Bruce, John’s son.

John and his son, Iain, take us down to a special little part of the property, where we set up camp – it’s hidden away and there’s an old cabin looking out over Bass Strait where the family used to camp out at night. Afterwards we head into Stanley for a quick look around (and a couple of frothies at the Stanley Hotel) before we go to meet Martin Hardy of T.O.P. Fish, who catch the octopus we use at Biota. In the notoriously turbulent waters of Bass Strait they set a total of 20,000 pots, lifting them when the weather permits. They primarily land octopus, but also catch abalone and crayfish. Martin shows us the facility, a processing area with large tanks that hold octopus, plus crays and abalone when they’re in season. We take some octopus to cook for dinner over the fire, and Cam spots a massive Southern cray he can’t resist buying.

Back at Western Plains, we light a fire on the beach, and while it gets going we spend the afternoon shooting clays together and catching up... John and Iain are dark horses when it comes to shooting – they turn out to be better shots than Cam, Adam and I put together.

The key to cooking over any fire is good coals, and when they’re ready we set about getting dinner happening: pasture-fed Cape Grim beef rib, octopus and crayfish. We don’t have an unlimited pantry, that’s not what this trip is about – it’s about real ingredients in their environment. There’s something pretty special about cooking beef on the land where it’s been raised, using octopus caught in the waters right in front of you, and of course Cam’s massive crayfish.

Fireside talks about deer populations in Tasmania.

We cook the beef rib, then leave it to rest. In the car, we’ve got some staples, such as butter, salt, pepper and a few sauces, but my idea is that we’ll build up our supplies as we go from location to location. So for this first dinner, it’s just chargrilled beef, crayfish split in half and cooked over the fire with butter and wild garlic, and seared octopus – simple, and yet amazing, when you consider that everything we’re eating comes from within 10 kilometres of where we’re sitting. The entire Bruce family, Adam, Cam and I sit by the fire and have dinner together.

After a long day, we eventually crawl into our swags. But barely ten minutes later I hear a strange noise. Shining the light outside, I see there are at least twenty penguins waddling around our tents. For such unassuming birds, these little guys make some serious noise, and they go at it all night!

Day 4

––––––

Launceston and Blessington:

butter and a deer hunt

We pack up camp and have coffee with John and his wife, Angela, then John takes us to see his ‘man cave’, a sort of trophy room lined with the mounted heads of animals he and Iain have shot. John and Iain are keen hunters and conservationists, and today we are all heading to Blessington, on the other side of Launceston, in search of deer.

Fallow deer first arrived in Tasmania in the 1830s, with a herd being kept in the Van Diemen’s Land Company’s Highfield enclosure at Stanley from 1837 until at least 1851. Subsequently, releases took place on private properties across central Tasmania for many years, and by 1975 there were large herds in several regions. However, the harvesting of bucks and protection of does caused a surplus of females – and due to overcrowding, poor nutrition and a deficiency of mature stags, many of these females failed to breed.

In 1994, a deer biologist was engaged to work with hunters, landowners and the government and make some recommendations on how to manage the wild deer population. These included a crop-protection tag system, and educating hunters to harvest antlerless deer, thus allowing young male deer to reach maturity. Some areas have ongoing problems with excessive numbers of deer, in part due to the more widespread use of irrigation – this results in lusher pastures and crops, which in turn attracts the deer, and Tasmania’s 5,000 licensed deer hunters play a vital role in managing the population.

But first, on the way through Launceston, I want to stop and see somebody I met a while ago, Olivia Morrison. Our paths first crossed when I was working on a dining event for the Melbourne Cup, based around Tasmanian ingredients, and I loved her passion and drive for doing something she believes in. She wasn’t working in the food industry at the time – she just loved good butter and saw a gap in the market for real butter made by hand, using locally sourced ingredients. She started making some of the best butter I’ve tasted, out of her garage in Launceston and now, a few years on, the Tasmanian Butter Company has expanded to bigger premises that include an on-site bakery and café called Bread & Butter, where we have a pit-stop for some lavishly buttered scones.

Love a scone, actually – with half an inch of cold butter in it.

A beautiful buck. It’s nice to be lost in the moment – this one’s just for watching.

When we arrive in Blessington, I notice the change in atmosphere. The altitude is higher here (about 600 metres above sea level) and the air is fresher; it reminds me of my home in the Southern Highlands. It’s beautiful, a landscape of pine trees and big gums, my kind of place. We drive over and through creeks full of running water to reach a small hunting cabin. Built for cold nights in the Tassie highlands, the cabin is full of history – kitted out with equipment that’s been left behind for the next time, it would surely have some stories to tell.

We unpack and get organised, and we all talk about our gear. Very important in these situations, gear! Next we start to look at the weather, what the wind is doing, when the sun sets and rises. And finally the deer: fallow deer, which is what we’re hunting, bed down during the day and feed at night. Our plan is to catch them as they move into open pastures or paddocks to graze the adjacent woodland, feasting on trees crusted in lichen. Something about walking quietly through the tall timbers, stalking deer, makes your senses come alive – your eyesight becomes sharper, your hearing heightened.

We’re out until about 11pm, taking a few shots at some deer on the edge of the scrub... When we miss, we decide to call it a night and head back to the cabin. With a fire going outside, we settle in for nightcaps and fireside chat.

Day 5

––––––

The Derwent Valley and Hobart:

adventures in fermentation

It’s a very wet morning, so we decide to leave the Bruce family to go about their day and drive on towards Hobart. Adam the photographer suggests we take the scenic Highland Lakes Road, climbing about 500 metres into an eerie and dramatic landscape of denuded trees. We reach a sort of plateau before winding our way down through some magical landscapes to the Derwent Valley, where we’re going to visit the Two Metre Tall brewery.

Back in 2004, Ash and Jane Huntington moved to their 580-hectare farm from a vineyard in southern France, chasing a dream of growing vines and making wine here. However, when they discovered a rich hop-growing history in the region, they decided on a brewery instead. Since then Tasmanian ingredients have become integral to the ales and cider they ferment in their converted shearing shed, giving them a sense of place and a connection to the land.

Full of enthusiasm, they start talking about weeds, native ingredients, wild fermentation and mash tuns. While Ash gets on with brewing a batch, Jane shows us where the magic happens and we taste a few brews, including their classic Cleansing Ale and a range of farmhouse ales. When Ash emerges from the shed, covered in the day’s work, he says ‘G’day’ and immediately starts talking about the variety of grains and plants they use. It doesn’t take me long to realise that any leaf or grain they find is going to be fermented – these guys are so passionate about their craft it’s infectious.

I’m fascinated to learn more about the specific plants he’s working with, so Ash leads the way into a small area of the shed that looks like a meth lab. With plants everywhere and wild ferments bubbling away, it reminds me of our workshop back at Biota. He starts by saying, ‘I’ve steeped this gear and got nothing. So it’s almost a waste of time. And then I thought, Aw, fuck it, I’ll just put a ferment through it and see what happens. And boom, it’s fuckin’ tasty and totally off the hook. First you ferment the natural oils that come out of the plants as they are heated, and then you’re starting to get all these aromatics and you’re just thinking, Oh my godfather, OK, here we go.’

I could stay here for days talking wild plants, ferments and gnarly flavour profiles... But we have to push on to Hobart, where we need to put Cam on a plane back to Sydney before we head off to meet another bloke who’s equally passionate about fermentation.

Adam James first became interested in fermentation while travelling through Japan. He recalls the exact moment: in a tiny sake bar in Kyoto he was served a snack of fresh tofu topped with a fermented chilli paste called kanzuri. The intense, layered flavour and complexity struck such a chord that he dedicated his life to trying to recreate it.

Previously at Hobart’s Tricycle Café, Adam has been dabbling in all things fermented for several years. Inevitably, hobby turned into obsession, and in 2016 he was awarded a Churchill Fellowship to undertake a ‘fermentation world tour’. His research took him to Denmark, Italy, France, Georgia, China, Korea and Japan, where he studied fermentation techniques old and new. He is currently focusing on expanding his range of fermented condiments, combining seasonal produce with traditional methodologies.

I ask if there are rules and formula involved. ‘Totally’, he says. ‘If you go to Japan and make miso, which I did in this sixth-generation miso house, they’re very strict about how you do things. I was telling him about the kind of stuff I’m doing now with koji, which he’d taught me how to make. And he’s rolling his eyes, as if to say “you crazy white man” kind of thing. For six generations he hasn’t moved outside that formula. But for me, it’s all about opening it up. I take a traditional technique and fuck around with it, putting it into a Tasmanian context by using whatever I can get locally.’

Adam also experiments by fermenting vegetables on their own – for example cucumbers and tomatillos – and then blending them, just as you would with different grape varietals for wine. ‘That one worked really well: these green summer vegetables were all high in acidity, so throwing them together was fucking outrageous. Super-good. With fermentation, playing around is how you get results, tasty results.’

I could happily settle in at Adam’s house for a while, especially as he has an epic vinyl collection and we might even get to taste some of the special miso he keeps hidden out the back somewhere – he’s always trying different flavours and ingredients. However, we have to go if we’re to catch the last ferry for the short hop across to Bruny Island.

It’s an overcast evening, and as it looms out of the mist, Bruny has a certain calmness about it, a sense of being untouched. While Adam is taking some shots of the sun punching through the clouds, I stand there in the freezing night air and think about my kids at home. It’s been less than a week and already I miss them.

Bruny Island is actually two land masses – North Bruny and South Bruny – joined by a sandy isthmus. We find a caravan park at Adventure Bay, on South Bruny, and we wheel in there and set up camp in about six minutes. We’re getting good at this.

The place is deserted: it reminds me of the trailer-park scene in Con Air, but with gum trees. There’s a caravan in the corner not far from us, and there’s a massive barney going on inside. The night is dead-still, so you can hear every word... I guess it’s all part of the experience. The weather is shit – cloudy, grey and wet – and what we really need is a hot shower. We find the coin-operated shower, a first for me. I love the idea of a coin-operated hot shower. But I drop my second dollar, and when I look down to where it landed I decide against foraging for it in the drain, so my shower is cut short. I got the important parts washed, though! We head to the pub – you can’t miss it, it’s the only one on the island – for some frothies and hit the sack.

Day 6

––––––

Bruny Island:

wakame-wrapped sea urchins

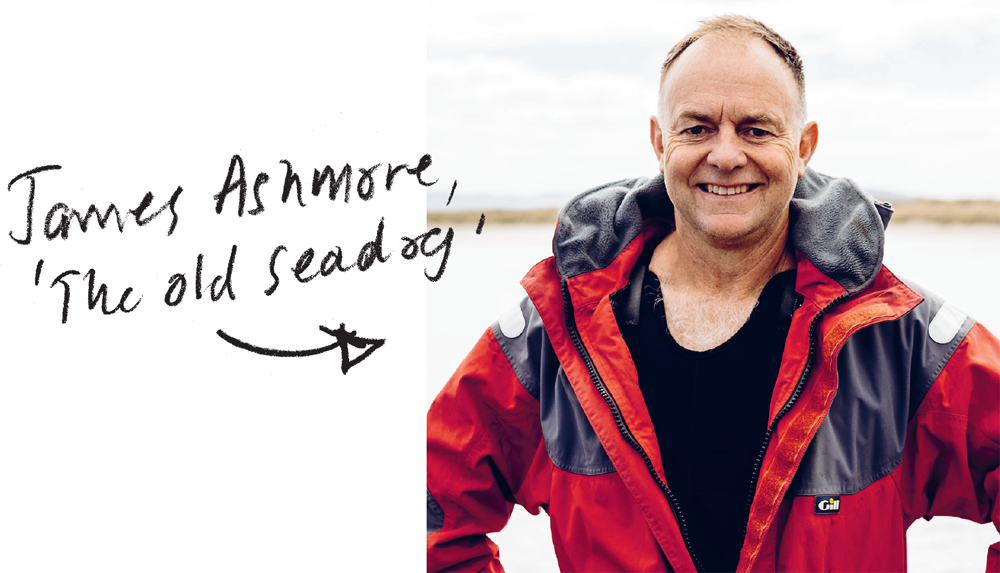

Next day we’re up early to meet James Ashmore, the owner of Ashmores Southern Fish Markets, who supplies our restaurant with lots of seaweed and sea urchins and some southern calamari. I first met James a few years ago, when we talked about seaweed and his love of the water, and he’s keen to show me the rich marine environment here.

It’s about 7 in the morning, and Adam and I are hankering for a decent coffee. It’s good to go on a trip with a bloke who drinks as much coffee as I do (before lunch). Hardly anything is open, so we end up in the ferry terminal, and the coffee is seriously crook – milky and warm. Not what I need before I jump into the brisk waters of the Southern Ocean...

At Dennes Point, we get changed into our wetsuits and wait for James. Eventually he scoots round the corner in a heavy-duty wetty, which makes me a little nervous. He’s a mad keen surfer as well, and he’s already been checking out the surf.

‘What’s the water temp, mate?’ I ask.

‘Oh, I think it’s about 5–7 degrees,’ he says.

Now if you ask me, that’s fucking cold, even if you do have some coverage on you.

Looking back, this was the hardest morning on the trip for me, because it was so cold. I was really hoping that I wouldn’t have to go in the water – I’ll do anything on the land, but I’m not fond of going underwater.

So, naturally, James says, ‘OK, we’re going in. We’re going to look for urchins and abalone, and see what seaweeds we can find.’

Adam manoeuvres the tinny into position and we jump into the water. It’s like ice, and there’s a strong current. James points out some of the seaweeds we use at the restaurant: frilly mekabu, ribbon-like kelp and the serrated fronds of wakame. It’s amazing to see them in their natural habitat. When we buy the seaweed from him it’s already been processed and packed in a beautiful little bag. It’s a stunning product, really fresh, and contains different varieties depending on the time of year. All of them have distinct flavour profiles and textures, and some are used in cooking, while others are eaten raw. We pull up a selection of the seaweeds, so we can take a closer look at them. They appear totally different out of the water, with contrasting kinds of light on them.

All this time I’m swimming through 5-degree water in a 2mm surfing wetsuit that I usually do stand-up paddle boarding in. It’s completely freezing, but put all that aside and you’re swimming through this forest of seaweed that just keeps going and going. There must be 300 or 400 metres of it around the point, just waving in the water, with the sunlight starting to come through in the early morning.

Checking out the catch with James.

James introduced me to this little number a few years ago. I’m going back for more.

The whole time I’m thinking about sharks too, because James had said there’s been bull sharks around, and it’s dark still. Now I don’t know if he’s just said that to make me shit my wetsuit – but I wouldn’t be able to spot them anyway, because with all the seaweed you can’t see more than a metre in front of you...

James goes down a lot deeper with a diving hookah on and comes up with some stunning sea urchins. The waters here are home to a mix of long-spined sea urchin, an introduced species, and the native Tassie ones, which are whiter and have shorter spines. The long-spine urchins are taking over, so there is a program to catch and sell them, to allow stocks of the native species to recover.

This bloke lives for the water, and soon we’re all sitting on the wharf, cracking open sea urchins. These are my favourite things – they remind me of ocean butter. Fresh sea urchins from the chilled Tasmanian waters, rolled in wakame plucked straight from the ocean. Hands down, this would have to be one of the best things I have ever eaten – a meal in itself, and our breakfast that day.

James keeps a short board in his tinny and is off to catch a surf break now, so we part ways. We drive over to the ferry terminal on Bruny (giving the coffee a miss this time) and head back to the mainland.

Day 7

––––––

Triabunna: scallops and mussels

We drive off the ferry and head north of Hobart to Spring Bay, near Triabunna, where Phil Lamb grows the mussels we’ve been using at Biota for almost five years.

On the way, we hit up the Triabunna fish and chip shop for some deep-fried ‘brown food’. Adam says we should get the scallops. Now I’m thinking of the mainland chip-shop version of scallops – battered potato slices, ideally dredged with chicken salt. But he offers me one and it’s an actual scallop. To be honest, I would have preferred my type of scallop, which in Tassie is called a potato cake, I’m told... WTF?

When we get to Spring Bay, Phil takes us out to his marine farm near Maria Island. The scenery is absolutely stunning, though I imagine it can get pretty gnarly out here on the water, especially in winter.

Phil tells me how it all began. They used to grow scallops, starting them off on the seabed, then dredging them up when they reached a certain size and putting them into lantern cages. But starfish ate too many of the young scallops – they tried all sorts of things, but in the end it just didn’t work. It was very labour intensive, and every two years the wild fisheries would open and the price for scallops would plummet, so they gave that away.

However, all was not lost, as they discovered that the ropes holding the scallop cages were getting covered in mussel spat. The beard, or byssal thread, of the mussel, which is secreted by a gland near the foot of the mussel, enables them to hang on to the rope. The young mussels quickly grew, so they started selling those and just kind of transitioned into farming mussels. The mussel beds now span about 1,500 hectares, and it’s the fast-flowing, deep water here that makes the mussels grow so well – it’s unusual to have such powerful currents in a water depth of 25–35 metres. The mussels live on long ropes suspended vertically in the water, where they benefit from the flow of water carrying fresh nutrients to them, growing large and plump.

Algal blooms for growing oysters and mussels.

We head back to Spring Bay, where Phil shows us his latest project, a room where they grow algae, which they then use to grow oysters from scratch. It looks like a scene from a sci-fi movie, with large plastic sacks full of living organisms. Through a carefully timed and exacting process, oyster seed stock is fed on the algae until the young oysters reach the size of a pinky-finger nail. They are then sold to oyster farmers all over the country, who grow them on to full size.

By now Adam and I are both hanging out for a coin shower and a frothy. Happily, the Triabunna tourist information centre has an amazing coin-operated shower, the best I’ve experienced to date – I’m becoming quite the expert now. Then it’s off to the Triabunna pub to rip the scab off a cold one... Boags XXX, of course.

Day 8

––––––

Leap Farm and Maria Island:

goat’s cheese and calamari

Our next stop is Leap Farm, Copping, a small pocket of Tassie near Bream Creek, where I’m catching up with Iain and Kate Field. They produce Tongola goat’s cheese, which we use at the restaurant for special dinners and events.

When we arrive, it’s bloody mayhem... I have never seen so many kids! Iain and Kate are both out on the farm: Iain is flying a drone over the property to try and spot some stray goats that have decided to go into someone else’s paddock for a quick arvo snack, and Kate is milking.

The ribbons for lost kids.

It’s late arvo, so we head back to our camp on top of the mountain overlooking Marion Bay. This place is beautiful: fertile rolling pastures, massive rock formations and coastal air from a wild ocean. One of Adam’s mates who lives nearby drives up the mountain to say g’day, really nice bloke, and we all sit by the fire and have a few tinnies.

Suddenly I start to feel pretty average. Now I never get sick, I have iron guts, but I reckon that scallop from Triabunna chip shop wanted out, and it was willing to take the fastest route possible. It knocked me for six for about three hours, then I was like a new man.

Iain and Kate moved from the mainland to Leap Farm in the height of winter 2012. They wanted to escape from the city and seek a lifestyle with more simplicity and depth. The goats are considered part of the family and are all individually named. Every one of their goats is matched up, with coloured ribbons for each mother and kid: blue goat, pink goat, green goat. It’s quite amazing to see fifty-plus kids find their mums in a paddock.

They tend their land according to robust organic and ecological principles, sowing thirty-four species of meadow plants and grasses to promote diversity. In the paddocks they have cattle and goats, which are complementary species, grazers and browsers respectively. They also have managed blackberry clumps to ensure a good supply for the goats, who can’t seem to get enough of it.

Iain and Kate pride themselves on taking a natural approach, following the natural lactation cycle of the goats and milking only once a day. Their milkers rest for three months while they’re pregnant, and the kids stay with their mothers until weaning.

All their cheese is handmade on the farm, with deliberately gentle milk handling and processing practices in place. A big part of their philosophy – and something I particularly like – is that they understand seasonal variation in the milk and embrace it in their cheesemaking.

Every single day, Iain and Kate feed all the kids with a bottle – this is full on, it’s relentless.

For us, just to be there for a few hours and see what happens in order to produce some of the country’s best goat’s cheese is unforgettable... not an easy gig.

We jump into the car and drive back up to Triabunna wharf (bypassing the scene-of-the-crime fish shop), where we’re going to meet a bloke by the name of Murray Knight to try and catch some calamari. Murray supplies the line-caught southern calamari we use at Biota.

Southern calamari would have to be one of my favourite ingredients, but I have never done this before. Like all fishing, it requires patience – and I have the patience of a red-headed stepchild, so I’m not going to last long. We boost out there in his tinny, and the thing is covered in squid ink, so I’m guessing we’re in with a chance.

After we’ve been out for about an hour, listening to a bunch of stories from Murray, I’m starting to wonder if we’re going to catch anything. Suddenly, he spots another bloke on the water.

‘Look at that maggot,’ he says. ‘I’ve been doing this for years and then these young blokes come in and just fish where I’ve been, but I have a secret spot up my sleeve.’

We head over to a sandbank off a rock ledge and throw a jig in... Boom! A calamari chases the jig and takes it. Now these things are predators, they attack. Murray pulls it in and lands it on the deck, and it’s massive. ‘A male,’ he says, and two seconds later it shoots its load (of ink) all over Adam. I reckon he’s had that happen before, though, as it doesn’t seem to faze him too much, and we spend another hour reeling in some more calamari.

We get back to shore covered in ink and keep heading north, until Adam asks, ‘Where are we staying, Viles?’ I haven’t really thought about it and figure we’ll just pull over to the side of the road somewhere – everywhere up here is stunning – but Adam thinks we might be able to stay on a farm near Triabunna, owned by another of his mates. We stop and say g’day, then head through the fields of Hereford cattle, windows down in the car, smelling the salt air. Adam says, ‘Wait till you see this place, Vilesy...’

Southern calamari, one of my favourite ever ingredients.

We unpack the car, set up camp and go for a walk over a sand dune dotted with samphire, warrigal greens, sea parsley and saltbush. The only tracks on it are those of small animals and over the other side is a beach with white-as-white sand, orange rock formations at its south end and crystal-clear water – it’s bloody cold, though. I have a few rigs in the car for salmon fishing, so we decide to walk around the rocks and throw a few lures in... and just like that, we soon have a small salmon and some parrot fish. That’s dinner taken care of, so we head back to camp, open up a few frothies and light a fire. To start with, we cook some vegetables with eggs in a skillet over the fire and scatter over some goat’s cheese from Leap Farm. Then we throw the fish on the grillplate and sprinkle over some dried abalone. The fish is unreal, the perfect meal. We hit the sack, and it’s one of the best night’s sleep I’ve had on the trip so far.

Day 9

––––––

Bicheno: another deer hunt

The next morning we’re up early, ready for another go at deer hunting, this time near Bicheno, a small coastal town that backs on to a large national park. In town I look around for some ammo as I have run out. There’s no sports store or ammo shop, but the local grocery store sells ammo, so you can buy your Winnie Blues, a case of tinnies, some Aussie-nan ‘white bread’ and some ammo all at once (only in Tassie).

We’re fortunate enough to be staying in a cabin on the property where we’ll be hunting. It’s surrounded by dense woodland, and when we open the doors, there are deer antlers mounted on the walls, and shells and rifle parts lying around – a true hunter’s cabin. We set off to scout out the best place to build a hide and settle on a small clearing in a field of fresh grass, building our hide down wind.

Adam and I go back to the cabin and put dinner on. We have some goat meat from Leap Farm in the car fridge, so I put on a goat curry and leave it to slow-cook for a few hours while we go hunting.

We sit in the hide for an uneventful two hours, then Adam spots a couple of fallow deer. Problem is they’re about 500 metres away, too far for a clean shot – and by the time we decide to move closer to them it’s already dark and visibility is poor. It’s a shame, but I firmly believe that if the shot can’t be a clean shot, it’s not worth taking.

We head back to the cabin for our goat curry before hitting the hay.

Day 10

–––––––

St Helens: in search of abalone

Tonight will be our last night on mainland Tassie and we plan to stay in the Bay of Fires, which has been on my wish list for a long time.

The drive to St Helens is majestic – we go through a lot of small coastal communities, the kind of places where you could just forget all your troubles and live a simple life. We spend the morning in St Helens having a look around, go for a drive to the Bay of Fires to find a campsite, and lock one in – it’s magic, right on the water.

We’re here to meet a guy called Dave Allen, who’s super-passionate about anything that comes from the ocean, and has supplied seafood to some of Australia’s top restaurants. Adam and I head back into town to see him, but he’s running late so we decide to get some supplies to make a celebratory dinner, in anticipation of actually catching some abalone.

Eventually we find Dave. Almost a decade ago, he pioneered sea urchin processing in Tasmania, at Goshen, just inland from the Bay of Fires, and his enthusiasm for sea urchins is boundless. Soon we discover that we also both have a fondness for the southern mud (native) oyster.

Dave grew up in this area and knows it like the back of his hand. His seafood is great, and he really knows his stuff, but it can be a precarious way of making a living. He takes us a little further north for a dive. Adam goes in as well and comes up with a bag full of abalone – the smaller ones we put back, and the rest we keep. Dave comes back with us to share our last-night dinner.

Fireside abalone, cooked in beer, garlic and butter.

Now abalone can be a real bitch to cook, especially if all you have is a fire, but I think the best approach is to keep it simple: just fire, abalone, garlic, butter and beer.

You need to beat the abalone with a rock or the back of a heavy frying pan until a small crack appears on the top of the shell. Place the abalone in the pan, cracked side down, then add a little garlic and a dob of butter. Add enough beer to cover, as well as a massive fistful of butter. Cook for about quarter of an hour, then remove from the heat, cover the pan and leave it for half to three-quarters of an hour. Go for a swim or something, or just settle back with a few cold ones – the beer of choice for the abalone is Boags XXX or Furphy.

Now cook up some linguine, slice the abalone super-thin and then toss them and their juices through the pasta. So tasty – especially if you’re in the Bay of Fires, looking at one of the prettiest sunsets imaginable.

ADAM GIBSON

Photographer

Being born in Tasmania, I was, unbeknownst to me, delivered into an isolated and distinctive part of Australia. It was not until I started to visit ‘the mainland’ as a teenager that I realised just how much the island state’s separation had shaped my outlook and character. From this early connection to our oceans, vast wilderness and people, I realise now just how lucky I am to call Australia my home.

These thoughts lead me to think of a time before my family arrived in Australia, the time of the Aboriginal people and the precious connection they have to the land we share today – their sacred, ancient connection. The more I travel across Australia, the stronger my respect for the knowledge and spirit of the Aboriginal people grows.

Geographically and culturally, Australia is a land of great contrasts – and my life is built around the pursuit of contrast, of light and shadow, and of magic. For me, travelling across the country has given me the ability to truly appreciate the spirit of this place and its people, and the incredible visual opportunities that exist within it.

The chance to work with James on this project was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity... however, we’re already planning our next adventure, which is a testament to what a brilliant experience this book was to create. James and I share a common view on many things and working together on this book was a fantastic, hilarious and emotional trip that I will never forget, and I am honoured to be a part of it.