Into the Outback

––––––––––––––––

We’re about to drive some of Australia’s remotest roads, so we head over to the servo to get everything checked, fill up on fuel and top up our water supplies.

Day 20

–––––––

Streaky Bay to the Gawler Ranges:

snake country and gumbo

Today we’re headed for Wirrulla, a small town at the southern end of the Gawler Ranges Road. We’re all feeling slightly nervous and tired, and we stop on the way to do a driver change. The car is so full that there’s no space for the seat to go back. Adam is crammed in the back with a charging inverter for his camera equipment, a downloading setup for the shots and Ryan (happily, Rhino only needs space for a tinny and some darts).

I’m in the front, and I lose my shit over Ryan trying to adjust the seat and tearing his shirt in the process – not important in the scheme of things, I know, and I go for a walk to calm down. This is where a few weeks of living in such close quarters, missing our loved ones and putting up with each other starts to get to us...

All is soon forgotten when we reach Wirrulla, jump out and see the signs pointing north. It’s hot out, 32°C, and this marks the beginning of the wild part of the trip – a highlight for all of us, with no set appointments, just random encounters along the way. When you start seeing road signs saying ‘Last fuel for 400km’ and ‘Road closed’/‘Road open’, you know you’re off the beaten track, and this is exactly the medicine I think I need.

The stark landscapes of the Gawler Ranges are full of stunning rock formations, rare native bird species and the famed yellow-footed rock wallaby. We stop on a dried-out salt pan to stretch our legs and take it all in – it’s not long before we start to feel very alone out here. The reality hits us that we’re in the middle of the Outback, with nothing around for several hundred kilometres at least. This is the best feeling: the anticipation of what lies ahead as we drive 3,000-plus kilometres of dirt road all the way to the Gulf of Carpentaria is spiked with adrenalin. Some of the tracks we’re going to be travelling on aren’t even shown on conventional maps...

Night is fast approaching, so we pull over when we reach a crossroads with a stock route. The good thing is that we can set up our swags and get a fire going pretty quickly by now. We’re in snake country here – big tiger snakes and king browns, maybe the odd death adder as well. Not exactly the most comforting thought, factoring in the issue of sleeping in a swag. Adam and Ryan go looking for firewood. There’s only some low-lying tea tree scattered around and we can’t help noticing a lot of small holes in the wood where snakes might be lurking... Not too keen at all on disturbing one of these bad boys.

We get the fire going and fold down the tailgate of the Disco. I tell the boys I’ve got dinner covered tonight. It’s so nice to cook for your friends under the seemingly endless skies of the Australian Outback: no music, no sound, just nature and the crackle of the tea tree on the fire – which smells amazing, by the way. The boys crack open some tinnies. Rhino is already half-cut, it’s been a big afternoon. In the fridge there’s the tail-end of an old salami, along with some whiting and calamari we bought from the fish shop in Streaky Bay and some beach herbs we picked up in Whyalla, and it all goes into the pot to make a sort of seafood and sausage gumbo. We sit around the fire under the stars and enjoy the warmth and spice of the gumbo before calling it a day.

After about half an hour, just when we’ve all fallen asleep, we hear another vehicle coming and immediately get up to see what’s going on. We wait and wait. In the pitch dark, we can see lights, but they just don’t seem to be getting any closer. Finally a car goes past, and the guys yell, ‘G’day, mate!’, their arms hanging out the windows as they turn onto another road... We drift off to sleep again. The Rhino is snoring like a freight train – it’s more accentuated when he’s drunk. When it starts to rain in the night, Adam and I zip up inside our swags, but Ryan is passed out and the next morning he wakes up drenched and totally bitten by mozzies.

Day 21

–––––––

Kokatha land: windmills, wild goats, Coober Pedy and Marla

The next day we push on through the Kokatha indigenous lands, a vast expanse that encompasses some of the harshest and driest terrain on the Australian continent. The road quickly turns from soft red desert sand to slippery shale rock, and we have to slow down. Out here, I can’t risk any damage to the car, or to ourselves.

We finally arrive in central Kokatha, which is just a homestead really, with a lot of sheep fenced into large pens. I can’t help wondering how long it takes for livestock to be transported out from here, and I’m thinking the condition they’re in when they reach the abattoir must be pretty ordinary – we’re talking 400–500 kilometres from anywhere by now.

We stop and have a look at an old windmill just outside the settlement. There are a lot of the original Southern Cross windmills out here. Produced commercially from the early 1900s, they’re all supposed to be individually marked with a serial number. I look for a plate somewhere on it, but can’t see anything. It still seems to be working alright and pumping water, though, so we have a drink of the metallic-tasting water and a bit of a refreshing wash as well. In these parts, you have to take the opportunity to wash when you can!

Driving on, we come across a huge mob of wild goats, I’m talking 200-plus goats. They just meander across the track in front of us. Some of the bucks are massive and as we’re running low on food we’re tempted to shoot one for meat – but we’re in a national park and can’t use firearms without permission.

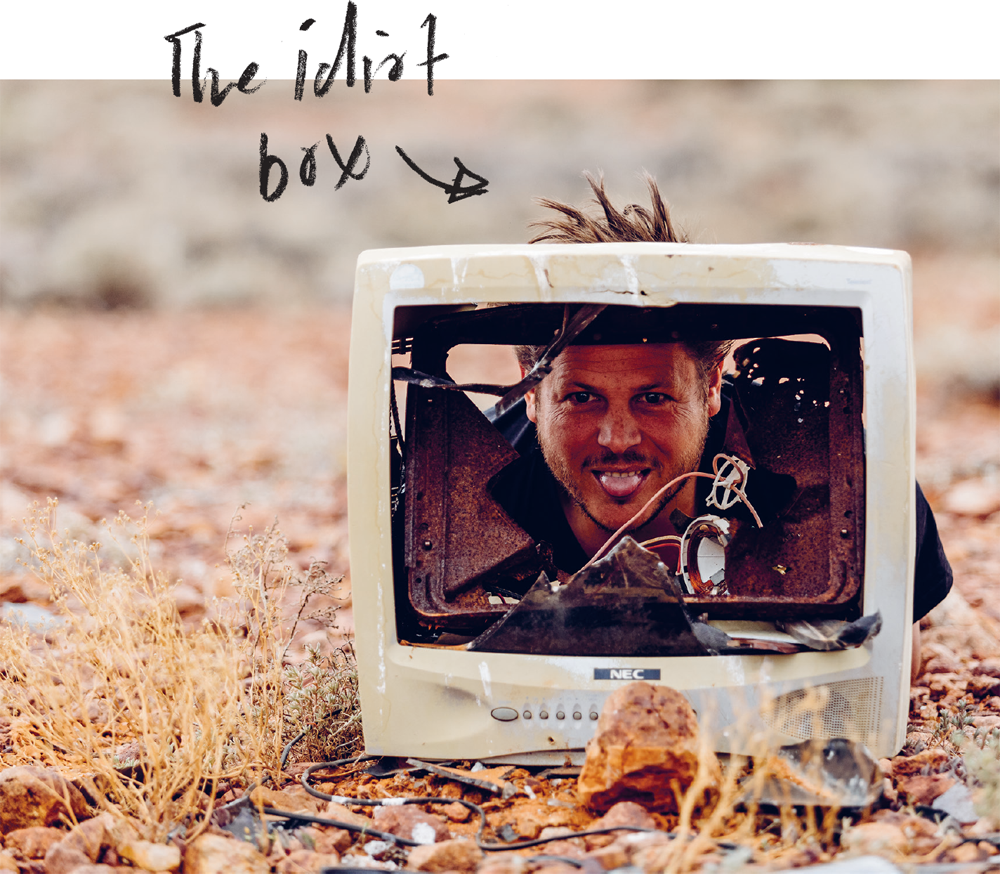

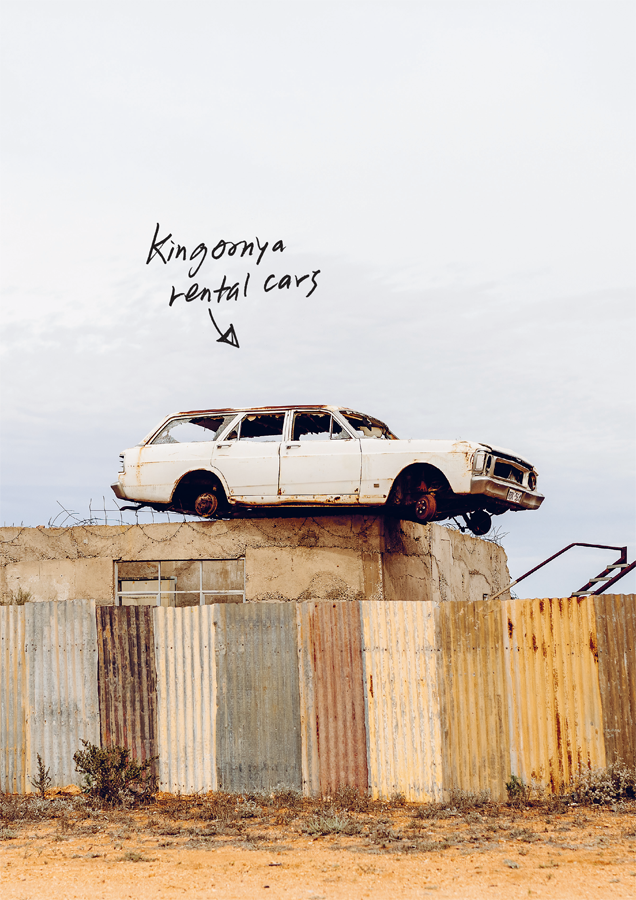

We eventually roll into Kingoonya, the first town we’ve seen in days of driving, and it’s pretty confronting: the houses, really more like sheds, are just standing. There’s an eerie atmosphere, as if the place has been forgotten. Once a vital link in the Trans-Australian railway, for many years the township relied on the Tea and Sugar train for its weekly supplies, but now trains no longer stop here and it has an abandoned air about it.

We were planning to stay the night here, but by the looks of it, I’d sooner sleep out under the stars again somewhere down the track. We pull up in front of the only public house – little more than a tin shed with XXXX written all over it – and peel ourselves off the car seats.

A bloke in a pair of stubbies and a bluey yells out, ‘Christ, she looks too low to be driving around these parts, mate!’ I explain that the chassis can be raised up and down, depending on the terrain, and we’d lowered it so we could easily get out. Well, he’s infatuated with it. Up here, it seems everybody drives a Land Cruiser, but the Discovery is holding up well, and so far all I’ve needed to do to keep this wagon on the road is pump up the tyres after a beach expedition. Touch wood!

After a few beers and a chat with some blokes who are also just passing through, we decide to move on. We’re headed towards Coober Pedy, about 400 kilometres away via Tarcoola. As we drive over the sand-covered rail lines, the road widens and quickly becomes full of sand ruts and washouts – this goes on for 250 kilometres until we hit the Stuart Highway, a long-awaited stretch of bitumen.

No sooner are we on the highway than we see a city runabout pulled off to the side of the road with three young backpackers alongside it, looking extremely lost and insecure. We decide to take a look. Now I don’t admit to knowing much about engines, but I do know when one is fucked, and this little car is well fucked. That’s what happens when you drive through central Australia with no oil. These kids had bought a car from a bloke in Coober Pedy, who obviously buys shitty little cars and then flogs them off to unknowing backpackers – this one had probably done three laps around Australia already.

We decide to leave two of them with the broken-down car and take the other guy, a young German, into Coober Pedy to sort the issue with the bloke he bought the car from. He jumps in the back of the Disco, squeezing in between Adam and a Remington 243. I’m sure Wolf Creek is crossing his mind by this stage, so we cover up the rifle with Ryan’s ripped shirt from earlier. When we drop him off at the bloke’s house, we feel like we should stick around to see what happens – but time is slipping away from us and we have to keep driving north.

We go off to explore Coober Pedy. We aren’t there long until we all start to notice the same vibe happening – and we’re not talking opals, but a bucket-load of crap ’Straya souvenirs. Every second shop is a souvenir shop, and the place feels strangely unreal, like walking through a Sim City... I guess that’s to be expected when you’re on the road more frequently travelled (same goes in life, really), but I can’t wait to pull off the tarmac and hit some dirt and diversity again, to connect with the natural world. Get me the fuck out of here!

We leave town on the Stuart Highway, happy to see the back of the big Hollywood-hillside-knockoff ‘Coober Pedy’ sign. After a few more hours behind the wheel, we reach a small town called Marla, still in South Australia. We feel like we’ve been driving for a bloody long time, and thought we would surely be in the Northern Territory by now; not the case.

The town takes its name from the Marla bore, which is itself a corruption of the Aboriginal marlu, meaning ‘kangaroo’. Marla is not very big, with a population of about 100, but it’s got a massive servo and an overnight campground, with hot showers – that’s right, hot showers! Unanimously we decide to wheel in, grab a roast dinner from the servo (pretty crook, actually) and then a shower to wash away the sins of our dinner choice.

Day 22

–––––––

The Stuart Highway to Alice and onto the Sandover Highway: desperate for diesel

Next morning, we get an early start and press on towards Alice Springs, a monotonous seven-hour drive away on the Stuart Highway.

On this trip I told myself I didn’t want to go to any of the big tourist attractions, especially if I’ve been there before. I didn’t want to visit sights just to get the obligatory shot, so if you don’t see a photo of Uluru (Ayers Rock) in here it’s because I’ve been there already, and because you can Google it. I was after the kind of images and experiences you can’t Google – the real Australia and the spontaneity of meeting people in the most unlikely places.

One of the local station owners near Marla. Great talks over a cold beer about their station, their land and its people.

We stop around the halfway point at a roadhouse in the middle of nowhere. It’s pissing down, which has me worried for the next 2,500 kilometres we are yet to travel. Remote roadhouses like this one usually have facilities like a bar (a must out here), a campground and a shop that sells the basic necessities and fuel. It’s about 11am, and we sit down in the bar area, which is completely empty apart from three indigenous guys who own and operate a huge cattle station nearby, as well as this roadhouse. They are kicking back until the rain eases, and we enjoy having a chat with them about their lands, and what the future holds for the land they farm. Also, one of them is a shark on the pool table: I have a few rounds with him and then call it once I’ve been beaten more than a handful of times.

When we jump back in the car and head north to Alice Springs, it’s still pissing down... If the Wet settles in, we won’t be able to keep going. When it’s been dry for so long and the land is arid, the water just sits on top of the soil and doesn’t seep in, meaning nasty, nasty road conditions, washouts and real danger.

We don’t stay in Alice for long. Really, the only reason we’re here is the airport: we’re dropping off Adam, who needs to check in with his young family after being on the road for a few weeks, and picking up Tim West, the sous-chef from Biota. While the boys get a late lunch, I do some ringing around: I’m trying to get a gauge of the Sandover Highway, some 750 kilometres of dirt track that heads northeast towards Queensland. It isn’t used much, and for most of the way you are crossing the traditional lands of the Alyawarra people. It has unknown hazards – sandhills, corrugations and black-soil plains that are an impassable quagmire after rain. During the Wet, Alpurrurulam (Lake Nash), near the border with Queensland, becomes completely inaccessible, so we are going to have to check on the weather conditions at Arlparra, an indigenous community about a third of the way along.

For months I’ve been researching this road and getting no real answers. I call the local police stations, but they don’t know a lot either – all they say is that it’s remote. We’re carrying plenty of water and spare fuel (apparently the longest run between fuel stops is around 320 kilometres), and our car is equipped with Hema off-road maps and access to real-time satellite weather information...

Soon we find ourselves at the start of the Sandover Highway, about 200 kilometres from Alice. It’s unnerving to think that we’re about to drive on one of the most remote roads in Australia, with no network coverage and no idea of the road conditions. The sky is blue, with low grey clouds scudding across it, and the track is sticky from some earlier rain; not too bad, though. But the sign says it all: ‘Dangerous road conditions ahead’.

Tim, Ryan and I step outside the car to talk about whether or not we do this, or just go on the Plenty Highway instead. I’m in two minds. I’m doing this trip because I want to see this country for all its challenges. I want it to challenge me to my fullest, and I also hope it opens the hearts and minds of my fellow travellers. Just as we are trying to decide, a white Falcon comes charging down the track: it’s missing its front bumper and the back bumper is hanging off. I walk out into the middle of the road to flag down the people in the car so I can ask them what the conditions are like. They stop, reluctantly (I wouldn’t stop for me, either), and I see they’re an Aboriginal family. I ask about the road, and in a very deep, almost shy voice, the driver says, ‘Good’, and then drives off. In this moment, I’m thinking to myself that maybe I really don’t belong here. The guy spoke in broken English, which is of course fine – it’s us who are the strangers here, passing through Aboriginal lands – but, for a fleeting moment, standing there in the heart of this country, for the first time in my life, I feel like I don’t belong here, like I’m a guest, and it’s a good, honest feeling in a way.

Excited at the news that the road is passable, we all jump in the Disco. The boys are saying, ‘We’re doing this’, ‘We gunna do this’. We want to calculate the fuel usage, and the car starts to work out what fuel we will need as it adjusts to the road conditions. We’re sitting on 70 kilometres per hour and the road is okay, a little sandy with some pretty soft edges, but I pick a line on the top of the road and stick to it. We notice that we’re not seeing any kangaroos or wildlife, the odd eagle but not a great deal of emu or anything else; it’s just such a different landscape. It is vast, and the soil is the reddest soil I’ve seen. There’s spinifex everywhere and it’s flat.

We’re only about 30 kilometres in when the road starts to get nasty, with sand ruts and washouts that I’m struggling to see in the slanting afternoon light. It’s about 4pm and the day is disappearing. I drop the speed but that doesn’t help, so I set the Disco to ‘sand’ mode and increase my speed to 80 kilometres per hour. It digs in like it’s on rails – what a beast, it’s just eating up these conditions.

We stop for a roadside dinner about two hours from Arlparra, and I go for a little wander to see if there’s anything other than spinifex. I don’t see any trees or signs of food, and we don’t want to camp just anywhere as a lot of the land here is native title, which means we can drive through on the road, but can’t go off-road without written consent from the community. Dinner consists of cooler leftovers – nothing to hunt and no water to fish in means slim pickings, but we’re all keen to eat quickly and push on, as we have a long road ahead of us.

We finally reach Arlparra, where we need to fill up on fuel. We have around 400 kilometres’ worth of fuel left in the tank and about 40 litres in cans on the roof, so we might make it, but there’s no buffer. Our fuel calculations are based on the assumption that we make it out the other side and don’t need to turn around, so I want to fill up as a precaution.

When we pull in, it’s like a ghost town – the small petrol station is empty and the bowsers have locks on them. Now, for those who’ve never been to an indigenous community in the Outback, it’s an eye-opener. The modest houses are more like tin sheds and are built directly on the ground, there are no gardens or grass and it’s bloody dry out here. However, it’s a community, and there’s a school (I actually contacted them to see if we could stop and do some cooking with the kids, but they were on holidays when we were passing through, which is a shame).

I decide to go for a walk to find somebody, but I can’t find a soul – apart from two guys hanging out of a car doing burn-outs about half a kilometre away, and I decide to leave them to it. By now it’s getting late and dark. As I’m wandering around, the setting sun is creating shadows on the walls of the buildings and around the baseball court and I notice they’re painted with beautiful indigenous artwork. It takes a little while to tune in to it, but there is a lot of beauty in this place. Later I find out that Arlparra is in the Utopia region, which is world-famous for its Aboriginal art.

We push on towards Alpurrurulam, about another 600 kilometres, give or take... By now, it’s dark and we are officially worried about our fuel situation. On the maps I notice that there is a cattle station nearby. Now most of the stations round here are not too keen on people entering their property – what with it being so vast and so remote, there is a lot of livestock theft, as well as burglary. And normally, there is nothing worse than driving off the main road into an unknown place, let alone somebody else’s home, without any warning or prior arrangement, but we are desperate.

Local artwork in a covered shelter in the community of Arlparra.

We drive through the big entrance into Ammaroo Station and up to the work shed, where a young bloke in a skid steer is packing up for the day. He doesn’t notice us and walks on inside. As he’s walking across the perfect green lawns, surrounded by bull dust, I call out, ‘G’day, mate!’ He turns around and says, ‘G’day’. I stay where I am, so as not to intrude, and explain that we’re looking to buy some diesel. He yells out, ‘Mum, somebody’s here...’ A lady who looks like she has talked to every bloody bull in every paddock comes out. I mean, these guys look like they work so fucking hard each day, and here I am at their family home, pestering them at knock-off time for fuel. I feel pretty bloody bad. I can tell she’s wary of us, not unreasonably, but she says, ‘How can I help?’ I ask if I can buy some fuel. Anna, her name is Anna, says, ‘Sure, how much worth?’ I scramble around the car for money, and we find $40 between us... that should give us enough to get to Gregory Downs at least.

There’s something about travelling through the bush and meeting people like Anna. I don’t know Anna and her family, but what I can tell you is that genuine, good-hearted and kind people are everywhere around us. Anna, you and your family saved our asses that day – and if you ever read this book, thank you.

By now we’re all wide awake and decide to just keep on driving... We’re not sure of the road ahead and it’s dark, but the night sky is the brightest I’ve ever seen. Tim is having a nap in the back and Rhino and I are up the front. The track is alive at night with tiger snakes that span the entire width of the road, and the headlights cut through insects the size of small budgies. I’m on a mission: this road requires complete focus, even more so at night.

I take a look at the maps, comparing routes and tracks. The decision to be made is whether to stay on the Sandover all the way to Alpurrurulam and run the risk of road closures due to poor conditions, or turn off about 20 kilometres sooner, onto a track that will take us up to join the Barkly Highway and then into Camooweal, across the border in Queensland. The issue is that the other track is not mapped – it’s a road through Austral Downs, a cattle station that occupies an area of about 469,000 hectares. I decide to take the turn off: it’s a narrow road running along a fenceline and it leads to a closed gate that says ‘Private Propert’, but we open it and carry on driving. Most of these big stations have through-roads you can drive on, as long as you don’t venture off the road.

It’s about midnight now, and I’m starting to fade... Mind you, by taking this route we have essentially gone from South Australia to central Queensland, via the Northern Territory, in one massive hit. To give you an idea of the distances involved and the time it takes to cover them, we’ve just spent four and a half hours driving across just this one property. At one point I veer off the track to miss a bull standing in the middle of the road – this isn’t uncommon in these parts, and it’s pretty dangerous to be driving at night, but we can’t stop on Austral Downs, let alone make a camp, so we just have to keep going until we get to Camooweal.

We finally pull off the dirt onto the bitumen of the mighty Barkly Highway and drive into Camooweal, wrecked. We roll out the swags and sleep comes quickly.

TIM WEST

Biota, Bowral

Sitting at Sydney airport, I can feel myself getting more and more nervous, not because of the flight but because of all the unknowns. I have no return flight booked, no idea what to expect, and no idea what I’m doing, where I’m going, what I’ll see or eat, or who I’ll meet. All I have is a bag full of undies, a camera and a fishing lure that I had to fight airport security to keep – you’re welcome, Ryan!

James Viles, my boss and mentor, is going to meet me in Alice Springs. All I know is that we’re driving to be inspired: by the people, the produce, the land, the journey, the stories and the friendships. Essentially, this is an R and D trip for the next phase of Biota and I keep telling myself that I just need to take notes, take photos, listen and be open...

We’re soon in the middle of nowhere, and I can’t believe we just drove one of the most challenging roads in Australia at night. James was determined to get through it, no way was he stopping short of it – his determination is second to none. Next day we’re still driving off-road when we get a flat tyre. It’s over 40°C and we only have one spare, but I guess it wouldn’t be a Biota trip without some suspense! After nursing the car for three hours, it’s a massive relief to roll into a service station, where I eat the most amazing mango of my life so far. Warmed by the sun all day, it tastes incredible.

On the drive to Gulf Country I’m riding shotgun, quite literally. A rifle barrel is hard up against my thigh and, I’m not going to lie, it’s making me a little bit nervous. I’ve never really been comfortable around guns, and I’m not sure how I’ll get on if James asks me if I want to have a go at shooting. Note to self: if you see a boar, hit it! Or, as James says, ‘Do anything under the sun to kill it – it’s a bloody pest, Timmo, don’t feel guilty.’

When we reach Van Rook Station, it strikes me as an unbelievable place, like something out of an old American movie set in the Deep South, around Mississippi or New Orleans; it just has that vibe about it. Barramundi fishing as the sun sets is a pretty special way to end the day.