During the 8th century the intermarriage of Pictish and Scottish royalty began to produce leaders with claims to both kingdoms. Occasionally, Scots became kings of the Picts, although more often the Picts dominated the Scots. Yet there was also a strong sense of nationalism, and both populations fought for their independence.

The balance of power was upset by the arrival of the Vikings in the early 9th century. The Vikings conducted daring raids into the heart of Pictish territory, which the Scots saw as an opportunity to free Dalriada. In 834, as the Pictish king Oengus II faced a Viking raid in the north, the Dalriadan leader Alpin rebelled, forcing the Picts to split their army in two. On Easter Day the first Pictish army was defeated at the hands of the Scots, and Alpin marched north to attack the rear of the second Pictish army, who had successfully seen off the Vikings. In the second battle, however, the Scots were brutally defeated and Alpin slain by Oengus, who ‘cut off his head’.

Alpin was succeeded by his son, Kenneth, who allied himself with the Vikings against the Picts. In 839 the Picts suffered a disastrous defeat at the hands of the Norsemen in which the High King Eogainn, his brother Bran, and ‘numberless others’ were killed. The slaughter of the Pictish nobility and warrior elite opened Kenneth MacAlpine’s claim to the vacant Pictish throne and a chance to re-establish Causantin Mac Fergus’ dynasty over both peoples.

The vagaries of matrilineal succession meant that several others had an equal claim, and Drust IX actually took the throne. What happened next is unclear, but it is believed that MacAlpine attacked and destroyed the remnants of the Pictish army in 841, and then, according to legend, he invited the surviving claimants to the throne from all seven Pictish Royal Houses to a feast to settle things peacefully.

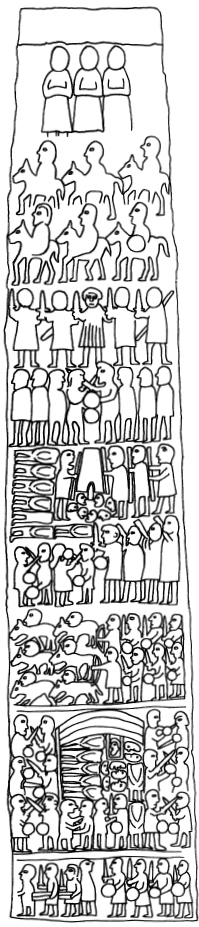

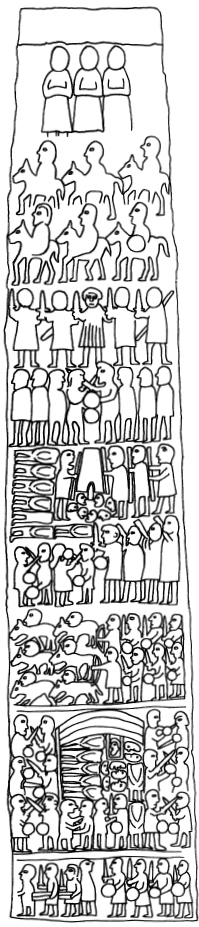

Situated in the town of Forres, the 6.5 metre-high (21 ft) Sueno’s Stone could be considered a Pictish ‘Trajan’s Column’. On one side is an intricate Celtic cross, and on the other are carved over 100 warlike figures. The badly weathered top appears to show three long-robed figures with crossed hands - perhaps there were once five, but they may also be the Holy Trinity or a depiction of the triplicate war-goddess. Below them assemble the cavalry and what is obviously the king and four companions.

In the middle third of the stone is a great battle. Champions duel before a watching crowd and battle-horns trumpet. Swordsmen follow archers into battle, preceded by what might be an uncharacteristically cramped attempt at more cavalry, or alternatively war dogs and their handlers. In the centre, staff-carrying priests ring a Celtic church quadrangular bell, signalling victory, and the stack of seven decapitated bodies and heads suggest a ritual beheading of captive enemies, perhaps one trophy for each Pictish king. The lower third shows a second battle, and at the bottom the victors chasing off the losers. There are more beheadings held underneath an arch or bridge. One head in particular is displayed publicly in a cage underneath the structure.

The stone dates from the 9th century, and there have been many suggestions as to what event it depicts. The style of the images, utilising dozens of small figures, is common on Irish crosses, leading some to theorise that it was erected by Kenneth MacAlpine to celebrate his victory over the Picts. However, Sueno’s Stone is a Pictish-style cross-slab, not an Irish free-standing cross, and the cross-side is carved with typically Pictish vine-scroll, indicating Pictish workmanship. Kenneth MacAlpine is also unlikely to have risked offending his Pictish subjects with such a provocative image of defeat and subjugation. The best clue to the subject is the fact that two separate battles are depicted, suggesting that it commemorates the double Pictish victory over the Norsemen and Alpin of Dalriada in AD 834, with the specially displayed head being that of Alpin himself.

They brought together as to a banquet all the nobles of the Picts, and taking advantage of their perhaps excessive potation and the gluttony of both drink and food, and noted their opportunity and drew out bolts which held up the boards; and the Picts fell into the hollows of the benches on which they were sitting, caught in a strange trap up to their knees, so that they could never get up; and the Scots immediately slaughtered them all… And thus the more warlike and powerful nation of the two peoples wholly disappeared; and the other, by far inferior in every way, as a reward obtained in the time of so great a treachery, have held to this day the whole land from sea to sea, and called it Scotland after their name.

While not exactly history, this story certainly explains how the Scots could inherit the land when ‘the Picts were far superior in arms’. Kenneth moved his capital to Scone and brought the relics of St Columba, including the Stone of Destiny. A hostile takeover by Kenneth is supported by the fact that the Picts resisted Scottish domination. After the short reign of MacAlpine’s second son, the capital was moved back to the Pictish seat at Fortevoit, and an attempt was made to revive Pictish matrilineal succession by bringing to the throne the son of Kenneth’s daughter by the ‘King of the Britons’, who reigned for ten years. For several generations the custom of matrilinear descent continued, but only within the MacAlpine dynasty, until in 858 Domnall I proclaimed that both Pict and Scot would live under one set of laws (a Dalriadan one), and the Scots and Picts were forever united.

In the end the Picts disappeared through a process of cultural colonialism. Gaelic replaced Pictish as the language of the nobility, Pictish fashions were replaced by Scottish ones, and Scottish myths and stories told by Scottish bards replaced Pictish tales. Early Scottish cross-slabs, though in the Pictish style and obviously created by Pictish carvers, show no Pictish symbols, suggesting that the outward marks of being a Pict, such as warrior tattoos, might mark one as an enemy of the king, and were quickly discontinued. The population began to be called Scots, as they lived in Scotland now, and their Pictish ancestry was gradually forgotten.