A MODEL INVESTIGATION

SURVEILLANCE TEAMS FROM London’s Metropolitan Police and MI5, the United Kingdom’s domestic intelligence agency, were staking out a brick house at 386A Forest Road in Walthamstow. It was late July 2006, and the weather was unusually hot in northeast London: 89 degrees Fahrenheit, with blue skies and a gentle breeze out of the southwest. Number 386A was a three-bedroom flat in a block of close-set houses. MI5 and the police were monitoring Abdulla Ahmed Ali and Tanvir Hussain, who had bought the flat on July 20 for about $250,000.1 Walthamstow is famous for its market, which stretches nearly a mile along High Street. In recent years the city’s Muslim population had swelled, and many of the families were of Pakistani descent. Large-scale immigration from Pakistan to Britain began in the 1950s; by 2005, according the British government, nearly 50 percent of Muslims in England were Pakistani.2

As Hussain and Ali walked into the flat, they sensed they were being watched.

“How is the skin infection you were telling me about? Has it got worse or is the cream working?” a contact in Pakistan asked Ali, using a Yahoo! e-mail account.3

British and American intelligence agents, who were monitoring their communications, believed the e-mail was sent by Rashid Rauf, referred to by Ali as Paps or Papa. A known al Qa’ida operative, Rauf had once been a member of the Pakistani terrorist group Jaish-e-Mohammad and was married to a relative of the group’s founder, Maulana Masood Azhar. Rauf was born in England to Pakistani parents, who brought him up in Birmingham, where his father was a baker. The CIA had been tracking Rauf on suspicion that he was involved in a number of terrorist plots overseas.

“Listen, it’s confirmed,” replied Ali a few days later. “I have fever. Sometimes when I go out in the sun to meet people, I feel hot. By the way I set up my music shop now. I only need to sort out the opening time. I need stock.”4

“Do you think you can still open the shop with this skin problem? Is it only minor or can you still sort an opening time without the skin problem worsening?” came the reply from Pakistan the next day.5

“I will still open the shop,” Ali responded. “I don’t think it’s so bad that I can’t work. But if I feel really ill, I’ll let you know. I also have to arrange for the printers to be picked up and stored . . . I have done all my prep, all I have to do is sort out opening timetable and bookings.”6

British intelligence officials, who had dubbed the investigation Operation Overt, believed that “skin infection” meant surveillance. Abdulla Ahmed Ali’s concerns were, of course, justified. British authorities hadn’t yet figured out exactly what the cell was planning, but they knew enough to become alarmed, especially on the heels of the successful July 7 terrorist attack in London a year earlier, which had killed fifty-two people and injured more than seven hundred others. In domestic and international intelligence circles, anxiety was growing that Ali, Hussain, and several of their friends were planning a major terrorist operation.

A Flood of Martyr Operations

Abdulla Ahmed Ali and Tanvir Hussain had raised no red flags as students. “They were normal boys,” recalled Mark Hough, a teacher at Aveling Park School, a secondary school of six hundred students that Ali had attended ten years before. “Ali was a good sportsman, a nice lad, and a typical fourteen-year-old.”7 Hanif Qadir, who ran a youth center called the Active Change Foundation, came to a similar conclusion: “Abdulla Ahmed Ali was a very upstanding young man.”8 Qadir and several colleagues had established the foundation in 2003 to provide a haven for estranged youth at risk for violent extremism, and Ali and several friends had worked out at its gym.

Ali, whom his friends dubbed “the Emir,” was now twenty-five years old, a husband, and the father of a two-year-old son. He was taller than most of his friends and walked with a self-confident swagger. His charismatic personality and candidness attracted friends and frequently placed him at the center of attention. “I would describe [Ali] as a strong character, someone who’s upfront, which I liked about him,” one of his friends later remarked. “He would speak his mind.”9

Ali possessed a good education and a degree in computer systems engineering. Born in East London, he was one of eight children from a successful first-generation Pakistani immigrant family. He had been devout since age fifteen, when he had become a follower of the Tablighi Jamaat movement, which had been founded in 1927 in Delhi to encourage Muslims to adhere more closely to the practices of the Prophet Muhammad. Ali had short-cropped hair and brown eyes. He kept his beard neatly trimmed, though it became patchy below his cheekbones, and he had a pockmark just above the bridge of his nose. Ali wore Western clothes and looked like a typical British young man. But privately he had developed a profound rage at the United States and Britain for their military operations in Afghanistan, Iraq, and other Muslim countries.

“Thanks to God, I swear by Allah, I have the desire since the age of fifteen or sixteen to participate in jihad in the path of Allah,” he bragged in a video produced in late July 2006, pointing his index finger at the camera. “Stop meddling in our affairs and we will leave you alone. Otherwise expect floods of martyr operations against you, and we will take our revenge and anger, ripping amongst your people and scattering the people and your body parts and your people’s body parts responsible for these wars and oppression decorating the streets.”10

Ali’s friend Tanvir Hussain was also twenty-five years old. Born in Blackburn, Lancashire, he had moved with his family when he was a young child to Leyton, a high-density suburban area of East London that boasted sizable numbers of ethnic minorities, including Pakistanis. In previous days the neighborhood had been home to the film director Alfred Hitchcock and the soccer superstar David Beckham. Hussain met Ali in secondary school. He went on to work as a part-time postman and studied business and information systems at Middesex University in northwest London. He was educated, gregarious, and a respectable athlete, excelling at cricket and soccer. He had an olive complexion, a crew cut that gave him a boyish look, dark brown eyes, and a short beard. His nose, which was crooked and jutted to the right, looked like it had been broken in a bar fight.

Hussain had dabbled with drinking, drugs, and girls in college, before finding Islam. He blamed the West for killing Muslims abroad and vowed to commit suicide to kill Westerners. “You know, I only wish I could do this again—you know, come back and do this again,” he shrieked into the camera in his own video confessional, “and just do it again and again until people come to their senses and realize, you know, don’t mess with the Muslims.”11

Links to Pakistan

What most alarmed British and American officials, however, were the young men’s connections with al Qa’ida operatives. One of the most notable was Rashid Rauf, who was the primary conduit between al Qa’ida in Pakistan and Abdulla Ahmed Ali and his colleagues. In 2003 and 2004, Ali had worked in Pakistan for a charity called Crescent Relief, which was run by Rashid Rauf’s family. He returned to the United Kingdom in January 2005 and then made several trips back to Pakistan in 2005 and 2006.12 When he returned in June 2006, British police and intelligence officials were sufficiently interested in him to open his luggage. Inside they found a large number of batteries, the powdered soft drink Tang, and other possible components of a homemade bomb.13

Ali kept in regular contact with Rashid Rauf and others in Pakistan via e-mail, text messages, and phone calls. The ability of the plotters to visit Pakistan, which many of them did in the years before 2006, and remain in contact with operatives such as Rauf transformed them from novices to professional terrorists. They became knowledgeable about explosives, including the use of hydrogen peroxide as a key component in bombs. Interacting with radicalized al Qa’ida operatives in Pakistan made them more committed to terrorism. They were savvier, utilizing countersurveillance techniques they had learned in training camps in Pakistan. They also had coaching, operational guidance, and encouragement from Pakistan during the planning process. Several of the e-mails, presumably from Rashid Rauf, prodded Ali and his colleagues to move faster. On July 20, 2006, Ali’s contact in Pakistan told him, “You need to get a move on. Let me know when you can get it for me.”14

The most senior al Qa’ida official involved in the plot was Abu Ubaydah al-Masri, al Qa’ida’s head of external operations, who had helped plan the operation from Pakistan. He had been an al Qa’ida commander in Konar Province and had worked his way to the top of al Qa’ida’s leadership structure. Rauf appeared to be a middleman between Abu Ubaydah al-Masri and the UK plotters. In addition, British intelligence identified one of Abdulla Ahmed Ali’s associates as Mohammed Gulzar, a native of Birmingham who had left the United Kingdom in 2002 after being implicated with Rashid Rauf in the murder of Rauf’s uncle. Galzar had returned to Britain from South Africa in 2006 under the false name Altaf Ravat.15

Another associate was Mohammed al-Ghabra, a twenty-eight-year-old Syrian-born naturalized British citizen who lived with his mother and sister in London. According to U.S. government documents, which were shared with the British, Ghabra had organized travel for several individuals to meet al Qa’ida leaders in Pakistan and Iraq and undertake jihad training.16 U.S. and UK intelligence agencies suspected that Ghabra was an al Qa’ida facilitator. In fact, the British began Operation Overt because they came across Abdulla Ahmed Ali’s cell when they were monitoring the activities of Ghabra and his network of associates.

American Concerns

By 2006 government officials on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean had become increasingly concerned about a terrorist attack against one or more airplanes in Europe or the United States. The FBI had sent MI5 a 2003 bulletin titled “Possible Hijacking Tactic for Using Aircraft as Weapons,” which warned that suicide terrorists might be plotting to hijack transatlantic aircraft by smuggling explosives past airport security and assembling the bombs on board. It concluded that “components of improvised explosive devices can be smuggled onto an aircraft, concealed in either clothing or personal carry-on items like shampoo and medicine bottles, and assembled on board. In many cases of suspicious passenger activity, incidents have taken place in the aircraft’s forward lavatory.”17

The CIA and other U.S. intelligence agencies helped track the cell’s support network in Pakistan, and the FBI and the Department of Homeland Security focused on links to the United States. Michael Chertoff, secretary of the Department of Homeland Security, chaired a series of meetings on Operation Overt, using the Roosevelt Room in the White House for several of them. Most of the participants, including John Negroponte, the director of national intelligence, were confident that the British had the investigation under control.18

At the FBI, director Robert Mueller called a meeting of his senior staff after being briefed on the plot. “Our first question should be, what are the plotters’ capabilities?” said Philip Mudd, who was deputy director of the FBI’s National Security Branch, which oversaw counterterrorism and counterintelligence investigations. “Is there an imminent threat? Do they have access to weapons and explosives?”

The advisers nodded. The answer appeared to be yes.

“Second,” he continued, “what is their intent?”

The available evidence suggested that they were targeting flights.

“Third, what are their overseas connections?”

The answer was disturbing. Ali and Hussain were in touch with al Qa’ida operatives in Pakistan. This connection made it one of the most serious plots—perhaps the most serious plot—targeting the United States since September 11, 2001.19

Others agreed. “As an operation,” remarked Art Cummings, the FBI’s special agent in charge of the Counterterrorism Division and Intelligence Branch at the Washington field office, “it did not appear to be just a homegrown plot. There were growing signs that it had al Qa’ida direction.”20

Cummings was a rising star at the FBI. His father had worked at the U.S. Department of Agriculture and later been assigned to Pakistan and Brazil, where Cummings spent time as a child. He attended high school in Bowie, Maryland, a suburban town 15 miles northeast of Washington, and served in the U.S. military as an elite Navy SEAL. He had also learned Mandarin Chinese, which came in handy when he investigated Chinese espionage cases for the FBI.21 By the summer of 2006, Cummings had settled into his job in the Washington field office. He hit the gym religiously, often sailed on the weekends, and most days carried a .40-caliber Glock. At forty-eight, he had magnetic blue eyes and a charming personality. But he was not afraid to be blunt, and Director Mueller occasionally chided him for having “sharp elbows.” When asked by the head of a prominent Muslim organization why the FBI was so interested in the Muslim community, Cummings was frank. “I can name the homegrown cells, all of whom are Muslim, all of whom were seeking to murder Americans,” he replied. “It’s not the Irish, it’s not the French, it’s not the Catholics, it’s not the Protestants, it’s the Muslims.”22 Cummings was intensely passionate about his job and now devoted his time to focusing on the airlines plot.

Long before September 11, al Qa’ida had considered using airplanes as weapons. Cummings and other FBI and CIA officials remembered Operation Bojinka, a failed plot by al Qa’ida operatives Khalid Sheikh Mohammed and his nephew, Ramzi Yousef, to blow up twelve airliners and their passengers as they flew from Asia to the United States. The plot was uncovered in the Philippines in 1995 after a fire at Yousef’s safe house brought him to the attention of local police. Files found on his laptop contained flight data on aircraft, including departure times, flight numbers, flight durations, and aircraft types. Yousef, who had been involved in planning the 1993 World Trade Center attack in New York, was eventually arrested in February 1995 in Islamabad by Pakistani authorities, with assistance from the United States. Abu Ubaydah al-Masri had apparently drawn on lessons from Operation Bojinka when instructing Abdulla Ahmed Ali and his network.23

Preparing the Bombs

In July 2006, MI5 and Metropolitan Police kept Ali under close surveillance, even watching him when he played tennis in the local park with Hussain and other friends. British security agents originally calculated that Ali’s and Hussain’s cell consisted of at least eight members. But they eventually discovered more than fifty potential members who were planning several waves of attacks, forcing MI5 and law enforcement officials to deploy nearly thirty surveillance teams to monitor the suspects. The security agents watched them around the clock, following them on shopping trips to supermarkets, pharmacies, and garden centers. One of their most unusual purchases was a large quantity of Lucozade and Oasis, energy drinks they found in local supermarkets. After a few weeks, there was a major breakthrough. British intelligence used an informant to get bugged phones into the hands of the cell members. This was to have a remarkable impact on better understanding the plot.

One day Ali met a young man in the park, well outside of eavesdropping range. The surveillance team followed the new suspect to High Wycombe, a town of about 100,000 people 30 miles northwest of London. British intelligence identified the individual as twenty-six-year-old Assad Ali Sarwar, who they soon discovered was the principal bomb maker.

Figure 1: Map of Greater London

Sarwar was heavyset, with dark bushy eyebrows, fleshy cheeks, full lips, and an overgenerous nose. Unlike Ali and Hussain, he didn’t grow a beard but sported a thin layer of stubble. Sarwar was an unemployed dropout from Brunel University, a medium-tier British school. At the time he was living with his parents in High Wycombe. Between 2002 and 2005 he held a variety of jobs: postman, shelf-stacker at Asda supermarket, security guard, and information technology worker for British Telecom. He had a reputation for being too direct, sometimes to the point of being boorish. He first traveled to Pakistan in 2003 with the Islamic Medical Association charity and met Ali, and he returned in 2005 when he met a man called Jamil Shah, who taught him how to make bombs. Sarwar’s role in buying bomb-making material and mixing ingredients suggests that he received more technical training in Pakistan than other members of the cell.

British intelligence soon discovered that Sarwar was mixing hydrogen peroxide with several other chemicals and storing the mixture in his garage. Hydrogen peroxide is a pale blue liquid, slightly more viscous than water. Most people use it for bleaching hair, cleaning cuts, and other household purposes. But when mixed with certain ingredients, it is highly sensitive to heat, electrical shock, and friction and can be ignited with fire or electrical charges. More important, it is a critical ingredient in such highly explosive compounds as hexamethylene triperoxide diamine (HMTD) and triacetone triperoxide (TATP), which had been used by al Qa’ida and other terrorists in previous attacks.

MI5 and police surveillance teams continued to monitor the brick building on Forest Road, but they needed to get inside to see what the cell was doing. One night when no one was home, a small team broke into the flat with a night-vision camera and videotaped the items Ali and Hussain had bought on their shopping expeditions, including the Lucozade and Oasis bottles. They also installed a camera in the wall to provide live pictures and sound. The position of the camera wasn’t ideal, since it showed only a partial view of the flat, but it was good enough to give British authorities a sense of what was going on. MI5 and the police were trying to understand everything about the individuals they were monitoring—they watched the suspects during the day and found out who their friends and associates were, which restaurants and gyms they used, and which Internet sites they surfed. They bugged their flat, tapped their phone lines, tracked their Internet and mobile phone usage, watched their credit card and bank transactions, and covertly monitored their movements, all in an effort to build as complete a picture of the terrorists as possible.24

While Ali and Hussain suspected British intelligence might be monitoring their movements, they had no idea that they were being watched on a live video link as they prepared ingredients for the bombs in the flat. Surveillance teams observed them as they drilled small holes in the bottoms of the energy drink bottles and took turns inserting syringes into the holes, extracting the sugary water, and squirting in a mixture of hydrogen peroxide that Sarwar had concocted. They then injected food coloring into each bottle, restoring the appearance of a sports drink, and filled the hole in the bottom so that the seal on the cap remained unbroken.

The homemade bomb was ingenious, though anyone carrying it onto a plane would have to partially assemble it after going through airport security. To set off the bomb, each terrorist was supposed to heat up a low-voltage bulb that was sitting in either HMTD or TATP, using power from a disposable camera. The explosion would then initiate the main charge—the hydrogen peroxide mix—and bring down the airplane. The terrorists also mixed Tang with hydrogen peroxide and other ingredients to color the liquid and create a more powerful explosion. Ali had scribbled notes to help him remember:

Clean batteries. Perfect disguise. Drink bottles. Lucozade, orange, red. Oasis, orange, red. Mouthwash, blue, red. Calculate exact drops of Tang and colour. Make in HP [hydrogen peroxide]. Check time to fill each bottle. Check time taken to dilute in HP. Decide on which battery to use for D. Note: small is best.25

If they could get the measurements right, a bomb in a Lucozade or Oasis bottle could contain half a kilogram of explosive. A bomb of that size could be catastrophic if placed appropriately on an airplane, especially in a pressurized cabin at 30,000 feet. Surveillance teams overheard the plotters discussing the construction of eighteen bombs for their attack, suggesting that the cell planned to destroy nine passenger flights in midair. Each cell member intended to carry two bottled explosives through security in case one of them was taken away.

In July, with British police and intelligence agents listening, Ali and Hussain discussed potential targets.

“I wanted to find out from the travel agent . . . the ten most popular places that British people holiday,” noted Hussain.

“We got six people in it. Me, Omar B., Ibo, Arrow and Waheed,” responded Ali, referring to the number of terrorists. “There’s another three units, there’s another three dudes.”

“There’s another three more, huh?” Hussain queried. “Seven, eight, nine, ten, eleven, twelve, thirteen—that’s 15 . . . 18. Phew! Think of it, yeah.”26

With the help of colleagues in Pakistan, the British terrorists had learned from past plots and attacks. Their decision to disguise the explosives as sports drinks was calculated to exploit vulnerabilities in airline security, which would enable them to smuggle the bottles through screening. In late July 2006, many cell members had applied for new passports by claiming that their previously issued passports had been lost or stolen. British officials believed that the new passports may have included pictures of the plotters that showed them as Westernized in appearance and would have erased all stamps and visas, especially to countries of concern, such as Pakistan.27 Moreover, the cell was clearly watching UK and international security agencies and their security practices and probing for weaknesses. The media coverage that had followed many of the previous plots and attacks, including the availability of transcripts from the legal trials of the accused, provided useful information for terrorists on government tactics, techniques, and procedures.

Furthermore, the plotters used coded language in their communications, referring to government surveillance as “skin infection” and “fever,” to their bomb factory as the “music shop,” to a U.S. airplane carrier as the “bus service,” and to a dry run of the attack as “the rapping concert rehearsal.”28 They were also careful to meet in large open areas that were beyond eavesdropping range, in some cases lying facedown to communicate to minimize detection.29

Trial Run

In mid-July, Ali’s contact in Pakistan, presumably Rashid Rauf, encouraged the cell members to go on a trial run to test airport security.

“Hi gorgeous,” he wrote. “Well nice to hear from you . . . Your friend can go for his rapping concert rehearsal . . . But somewhere popular would be good . . . Make sure he goes on the bus service which is most common over there.”30

British police and intelligence officers followed Ali into an Internet café, where he downloaded transatlantic flight schedules. He appeared to be particularly interested in United and American Airlines, as well as Air Canada. Surveillance teams then heard Ali and Hussain discussing possible destinations, including Washington, D.C., New York, Chicago, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Montreal, and Toronto. British authorities believed that the terrorist cell intended to explode the liquid bombs over the Atlantic.

Throughout their final preparations, the plotters maintained close contact with al Qa’ida operatives in Pakistan, especially Rashid Rauf, who provided operational and tactical guidance. While in Pakistan in June 2006, Ali had registered two e-mail addresses to communicate with Rauf. For one he claimed to be an American woman called Tippu Khjan from Shepherdstown, West Virginia. In the second address he used the identity Jameel Masood, again filling in “United States” under the location heading. Sarwar also set up e-mail accounts under false names.

Around August 3, British government officials informed their American counterparts that the plotters were probably planning to detonate the bombs on flights to the United States and Canada. This raised the stakes for U.S. officials. Willie Hulon, who headed the FBI’s National Security Branch, called Art Cummings at the Washington field office and placed him in charge of the FBI’s response. Cummings jumped into his Chrysler 300, switched on the flashing blue and red lights, and raced to the National Counterterrorism Center in McLean, Virginia. After being briefed on the intelligence, he suggested that the FBI begin issuing orders for wiretaps and physical surveillance of people in the United States who were suspected of having connections to the plot.

“Our focus,” he said, should be “Is there anything bad that could kill us here?” He told his agents, “Give me everything we’ve got on these guys. I need to know everybody who’s touched any of these guys ever in their lives, from the time they were born. Every person these guys have ever spoken to, paid, run into.”

Cummings’s list highlighted the complexity of the FBI’s response and the quantity of information that the Bureau needed to collect and analyze. He wanted to know “who went to school with them, had any type of contact with them, any type of communication with family members, friends of family, all of them. I want financials, associates, travel. Start giving me numbers that I can start working with.” But that wasn’t all. “Put on technical surveillance 24/7,” he continued, referring to twenty-four-hour wiretaps and electronic bugs. “Wake ’em up, put ’em to bed. Every single piece has to be reviewed and looked at, not just for threats but for opportunity.”31

By late July 2006, Assad Ali Sarwar had prepared the hydrogen peroxide. Some of it was later recovered from his garage in a boiled-down form, a concentration that could be used for an attack. Sarwar also buried a suitcase that contained bomb components, including thermometers, citric acid, hexamine, hydrogen peroxide, syringes, and glass flasks under the roots of a tree in the High Wycombe woods. In a nearby wooded area, search teams discovered 20 liters of hydrogen peroxide in 5-liter containers hidden in black garbage bags. “We found out we was under surveillance,” said Abdulla Ahmed Ali, “so I told [Sarwar] to hide it.”32

There were other disturbing developments. On July 27 surveillance teams listened to cell members putting together martyrdom videos at 386A Forest Road. Abdulla Ahmed Ali made his video using a Sony Handycam camera and angrily addressed Westerners. “Sheikh Osama [bin Laden] warned you many times to leave our lands or you will be destroyed,” he counseled. “And now the time has come for you to be destroyed, and you have nothing but to expect that floods of martyr operations, volcanoes, anger, and revenge are erupting among your capital.”33 The same day Tanvir Hussain produced a similar video warning that “collateral damage is going to be inevitable and people are going to die.”34

On July 31, British intelligence and police found two plastic bags in East London that contained wires attached to miniature bulbs with exposed filaments designed to spark liquid bombs. The DNA and fingerprints on the bags and material belonged to Tanvir Hussain. On August 7, British home secretary John Reid and MI5, worried that cell members had turned to final preparations and that attacks were imminent, alerted key cabinet members about the plot. On August 8 the secretary of state for transport, Douglas Alexander, was given a full intelligence briefing on Operation Overt while on vacation in the Isle of Man.

The next day Alexander flew back to London in a Ministry of Defense helicopter. The director-general of MI5, Eliza Manningham-Buller, updated him on unfolding events, noting that “there was an alleged plot to bring down a number of aircraft over the Atlantic.” She added that “there was surveillance of the suspects under way. And there would be an operational judgment made by the police as to the right time to take action against the individuals who were under surveillance.”35 Manningham-Buller was the daughter of Viscount Dilhorne, who had served as solicitor general, attorney general, and lord chancellor in Conservative governments from 1951 to 1964. Growing up in the company of ministers, she knew how to work with intelligence agents and government officials.36

Back in Washington, senior White House, Department of Homeland Security, CIA, and FBI officials were equally alarmed, and they remained in regular contact with the British. Art Cummings observed that U.S. government officials were growing restless because the British had not yet arrested the plotters. Indeed, British officials were willing to let the surveillance efforts continue in order to collect intelligence on the plotters’ support network. On Wednesday, August 9, Home Secretary Reid told colleagues that an attack “was not imminent. There was sufficient time left to take any action should it prove necessary.”37

That day cell member Umar Islam made a martyrdom video in the flat on 386A Forest Road. “If you want to kill our women and children, then the same thing will happen to you,” he warned. “This is not a joke. If you think you can go into our land and do what you are doing in Iraq, Afghanistan, and Palestine and keep on supporting those that are fighting against the Muslims and think it will not come back on to your doorstep, then you have another thing coming.” Umar Islam then acknowledged that he had been inspired by Osama bin Laden and Taliban leader Mullah Muhammad Omar. “Mullah Omar, Sheikh Osama, keep on going and remain firm. You inspired many of the Muslims and inspired me personally to follow the true path of the Prophet.”38

Ali directed Umar Islam during the videotaping. “Relax, don’t try and speak posh English. Speak normal English that you normally speak. When you mention Allah, do that,” Ali continued, extending his index finger upward and then moving it downward violently for emphasis. “When you’re making a point, point away, that hand movement, you’re warning the kuffar. Give a bit of aggression, yeah, a bit loudly. We’re higher than everyone else.”39

Umar Islam had narrowly avoided blowing the operation. A few days before, his wife had stumbled on the script of his suicide video, which had accidentally fallen out of his pocket. “I came in, I saw it on the table,” said Islam, referring to the script. His wife picked it up. “Is this what I think it is?” she asked. He retorted, “Don’t ask me no questions.”40 Despite his wife’s protests, he refused to explain or discuss the matter further.

The Arrests

By August 9, John Reid was still comfortable enough with the pace of the investigation that he attended a soccer game that evening between his beloved Celtic team and Chelsea in London at Stamford Bridge, Chelsea’s home stadium. But a development in Pakistan changed the course of the operation. Pakistan’s intelligence agency, the Directorate for Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI), arrested Rashid Rauf. British officials believed that once cell members in the UK heard about the arrest, they would stop planning and destroy the evidence.

The British were furious. The CIA, which had been monitoring Rauf in Pakistan, was concerned that he was preparing to go into hiding and had encouraged the arrest. He was believed to be developing several international terrorist plots in addition to the British one, and American and Pakistani intelligence officials wanted to interrogate him. U.S. government officials had reached their risk threshold. It unnerved them that the plotters in the UK were on the verge of launching an attack. As Michael Chertoff acknowledged, “We needed to bring the case to resolution before there was a serious prospect that it might become active.”41 Over at the FBI, Philip Mudd agreed. Rashid Rauf was targeting the United States, and there was a narrowing window of opportunity to capture him. Agents had good intelligence on his current location, but that might change in an instant. American officials were worried that he would go underground in Pakistan’s tribal areas, where CIA coverage was spotty. “If we didn’t catch him now,” Mudd argued, “he would likely disappear.” And they might not get another shot at him. “Rauf was a core plotter,” emphasized Mudd. “He was a big deal.”42

For Art Cummings, the capture of Rashid Rauf illustrated a lingering struggle between the CIA and the FBI. Rauf had been seized with his laptop, but the CIA refused to share the laptop—or the information in it—with the FBI. “The irony,” said Cummings, “is that we didn’t have enough information to prosecute a case against Rashid Rauf in the United States if the Pakistanis extradited him to us, even though they were unlikely to do so.”43

Senior British officials were stunned that they had not been given adequate warning of Rauf’s arrest. They had been caught completely off guard. Even more disturbing, Rauf soon escaped from Pakistani custody. He and his police escort entered a mosque in Rawalpindi to pray; Rauf went to the bathroom, jumped out the window, shaved his beard, and fled to Pakistan’s tribal areas. U.S. and British intelligence agents strongly believed that the police officers escorting him facilitated his escape. The United States eventually tracked him down, and two years later he was killed in a drone strike.

On August 9, 2006, however, with Rauf still in Pakistani custody, British police suddenly had to arrest a number of suspects whom they hadn’t planned to seize for several more days. “We believed the Americans had demanded the arrest and we were angry we had not been informed. We were being forced to take action, to arrest a number of suspects, which normally would have required days of planning and briefing,” remarked Andy Hayman of the Metropolitan Police. “Fearful for the safety of American lives, the U.S. authorities had been getting edgy, seeking reassurance that this was not going to slip through our hands. We moved from having congenial conversations to eyeball-to-eyeball confrontations.”44

At 9:30 p.m. on August 9, the UK government’s crisis committee, referred to as COBRA, held an emergency meeting in Cabinet Office Briefing Room A, which was in a secure cellar in Whitehall between the Houses of Parliament and Trafalgar Square and gave the committee its name. The room is linked to Downing Street, where the British prime minister lives, and other government buildings, such as the Foreign and Commonwealth Office and the Cabinet Office, through a series of corridors. John Reid chaired the meeting wearing sunglasses because of an eye infection.

The meeting included senior officials from MI5, the military, police, and other relevant ministers, such as Douglas Alexander. “There was an air of tension and determination,” Reid recalled.45 In light of Rauf’s arrest, the UK government decided to arrest the cell members immediately. The police then moved quickly, with the support of MI5.

That evening, Abdulla Ahmed Ali was saying his prayers outside his car, which was parked at Walthamstow’s town hall, when police found him. Assad Ali Sarwar was there as well. Ali’s notebook contained a list of ingredients: batteries, drink bottles, and hydrogen peroxide. In his pocket police found the USB memory stick he’d used to download information on transatlantic flights from the Internet café.46 They also found Umar Islam’s martyrdom tape, which had been produced only a few hours earlier.

“What’s this?” inquired the police officer who had grabbed Ali.

“A USB stick,” he responded.

“Whose is it?” the officer queried.

“Mine,” said Ali.

“What’s on it?” the officer continued, growing impatient.

“Holiday destinations in America,” remarked Ali.47

The game was up for Ali and his network. By Friday, August 10, all the main suspects were in custody and had been charged with conspiracy to commit murder.

A Victory

Operation Overt was a model investigation—one of the first major successes against al Qa’ida outside Afghanistan and Pakistan since the September 11 attacks. At the time, skepticism had been growing in the United States about whether al Qa’ida was still a threat. Operation Overt offered a stark reminder that al Qa’ida and its allies posed a serious danger to the United States and other Western countries. Abdulla Ahmed Ali, Tanvir Hussain, and Assad Ali Sarwar were eventually convicted, in 2009, of plotting to use liquid explosives to blow up airplanes, the culmination of an impressive effort by the Crown Prosecution Service, the UK government authority responsible for prosecuting criminal cases investigated by the police. Ali was sentenced to a minimum of forty years in prison, Sarwar to a minimum of thirty-six years, and Hussain to thirty-two years. Umar Islam was convicted of conspiracy to murder and sentenced to a minimum of twenty-two years in prison.

The intelligence collection and analysis displayed in Operation Overt was unparalleled. “We logged every item they bought, we sifted every piece of rubbish they threw away (at their homes or in litterbins),” according to one British police account. “We filmed and listened to them; we broke into their homes and cars to plant bugs and searched their luggage when they passed through airports.”48 The authorities sifted through every piece of intelligence imaginable. As British police later acknowledged, “When a key figure, Abdulla Ahmed Ali, returned from Pakistan in June 2006, we searched his luggage and resealed it without him noticing. Inside . . . were bomb-making components and their discovery led to a step change in the operation.” They also blanketed 386A Forest Road: “We were on their tail when Ali bought a flat in Walthamstow for £138,000 cash and we ‘burgled’ the property to wire it up for covert sound and cameras. We watched as they experimented with turning soft-drinks containers into bottle bombs, listened as they recorded martyrdom videos and heard them discuss ‘18 or 19.’ ”49

In monitoring the e-mails—and using them as evidence in court—the British reached out to American law enforcement agencies, which contacted Yahoo! headquarters in Silicon Valley, California, to secure the personal correspondence and account information of the suspects.50 Indeed, following a UK request, a series of court orders in January and February 2009 released the e-mails from a court of law in California. They were used as evidence in the trial.

Even before the investigation began, the UK had devoted a breathtaking amount of time and resources to meld its police and intelligence operations, especially Metropolitan Police and MI5.51 Peter Clarke, who served as national coordinator of terrorist investigations for Metropolitan Police, noted that “the most important change in counterterrorism in the UK in recent years has been the development of the relationship between the police and the security service . . . It is no exaggeration to say that the joint working between the police and MI5 has become recognized as a beacon of good practice.”52 The British government also adopted a strategy for stopping terrorists, referred to as CONTEST, which was divided into four components: pursue, prevent, protect, and prepare. “Pursue” included intelligence-gathering and other steps to identify terrorist networks and stop attacks; “prevent” involved deterring people from becoming terrorists or supporting terrorism; “protect” focused on hardening targets and strengthening border security; and “prepare” emphasized forward planning and other steps to mitigate the impact of a terrorist attack.53

Over the course of the investigation, the police seized a mountain of information contained on 200 mobile phones, 400 computers, and 8,000 CDs, DVDs, and computer disks that contained over 6,000 gigabytes of data. They searched nearly seventy homes, businesses, and areas such as public parks.54 In addition, the Bank of England ordered banks to freeze the assets of nineteen individuals suspected of participation in terrorist acts.55 In July 2010 three more individuals were convicted in Woolwich Crown Court of participating in the plot to blow up transatlantic airliners with liquid explosives: Ibrahim Savant, Arafat Waheed Khan, and Waheed Zaman.56 Several other apparent cell members were found not guilty of conspiring to murder.

It is difficult to overstate the significance of Operation Overt. It was established on the heels of several successful terrorist attacks linked to al Qa’ida: on September 11, 2001, in the United States; on March 11, 2004, in Spain; and on July 7, 2005, in the United Kingdom. In addition, al Qa’ida in Iraq had been conducting a series of attacks against U.S. and Iraqi forces since 2003. The transatlantic plot was a serious effort to kill a large number of American, British, and other civilians. As Michael Chertoff remarked, the 2006 airline bombing plot appeared “to have been well planned and well advanced, with a significant number of operatives.”57 The FBI’s Philip Mudd agreed: “It was the most intense plot up to that point after September 11.”58

Waves and Reverse Waves

Operation Overt proved a harbinger of things to come. Since al Qa’ida was founded in 1988, a series of waves (surges in terrorist violence) and reverse waves (decreases in terrorist activity) have characterized the struggle against the group. As political scientist David Rapoport described, a terrorism wave is a “cycle characterized by expansion and contraction phases.”59 Over time the ability of terrorist groups to conduct attacks in order to achieve their political goals waxes and wanes.

Terrorism waves are examples of a more general phenomenon in international politics: similar events sometimes happen more or less simultaneously within countries or broader geographic regions. Beginning around 1828, for example, democratization spread across the world, a development that political scientist Samuel Huntington dubbed “the first wave” of democratic advancement. This was followed by a second wave from 1943 to 1964, and a third wave beginning in 1974. Each wave saw significant increases in the number of democratic countries worldwide.60

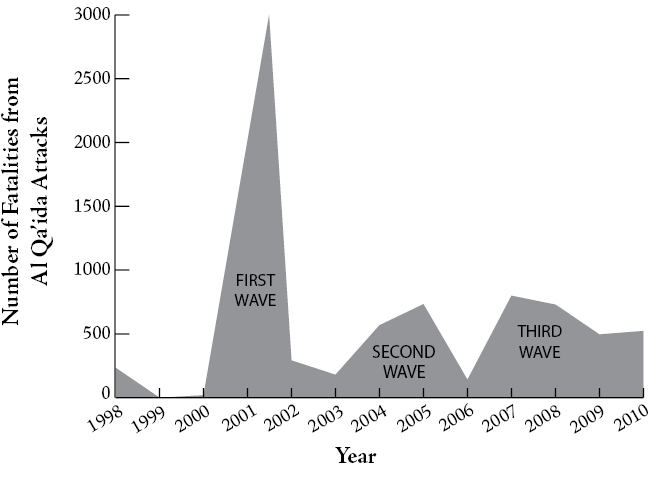

Similarly, al Qa’ida–affiliated terrorism has occurred in at least three waves over the decades-long lifespan of the organization. As Ayman al-Zawahiri argued in such books as Knights Under the Prophet’s Banner, one of al Qa’ida’s primary objectives in conducting attacks has been to kill as many enemies as possible.61 Consequently, the number of fatalities from al Qa’ida attacks provides a useful indicator of the group’s activity. Other data, such as the number of attacks, are less useful, since they don’t differentiate an operation that fails to kill individuals from one that kills several hundred people. For al Qa’ida leaders, this difference is important. Figure 2 illustrates al Qa’ida’s waves using data from the Global Terrorism Database at the University of Maryland. The data include fatalities caused by al Qa’ida and its affiliates in Pakistan, Afghanistan, Iraq, Somalia, the Arabian Peninsula, and North Africa.62

Figure 2: Al Qa’ida Waves

The first wave began with the attacks against the U.S. embassies in Tanzania and Kenya in 1998, followed by the bombing of the USS Cole in Yemen in 2000. This wave crested with the September 11 attacks and was followed by a reverse wave as allied forces captured and killed al Qa’ida leaders and operatives in Afghanistan, Pakistan, the United States, and elsewhere. A second wave began in 2003 after the U.S. invasion of Iraq and was characterized by spectacular attacks across Iraq and in Casablanca, Madrid, London, and other cities. A second reverse wave began around 2006, as the Anbar Awakening severely undermined al Qa’ida in Iraq, British and American intelligence agencies foiled numerous plots, and U.S. and Pakistani strikes killed senior al Qa’ida operatives in Pakistan. A third wave surged between 2007 and 2009, following the rise of al Qa’ida in the Arabian Peninsula, and was again followed by a reverse wave as the United States targeted Osama bin Laden and other senior leaders in 2011.

Wave Patterns

In light of these patterns, this book asks two questions: What factors have caused al Qa’ida waves and reverse waves? And what do the findings indicate about a fourth wave?

At first glance, there are several possible answers to the initial question. Perhaps wave patterns reflect a decision by al Qa’ida’s leaders to delay attacks and wait for an opportune moment to return to violence. But there is little evidence to support this argument, since al Qa’ida leaders have pursued plots consistently over the past decade. Research on terrorism highlights several other possibilities: terrorist campaigns have sometimes declined or ended because the leader was killed, there was a negotiated settlement, groups imploded or became marginalized, they were crushed by military forces, or they made a transition to criminal or other activities.63 But these explanations fall short. Al Qa’ida became increasingly decentralized over time, ensuring that the killing of its leader—Osama bin Laden—would not destroy the group. There have also been no settlements with any of al Qa’ida’s affiliates, the group has not imploded, the use of conventional military forces has actually strengthened al Qa’ida, and the group has not transitioned to other activities.

Instead, three factors help explain wave patterns: the counterterrorism strategy of America and its allies, al Qa’ida’s own strategy, and the competence of local governments where al Qa’ida has tried to establish a sanctuary. For all of these actors, the struggle has depended to a large degree on the precise use of violence.64 In many ways, it is a war in which the side that kills the most civilians loses.

The first is variation in the counterterrorism strategy of America and its allies. As in most counterterrorism campaigns, the United States has utilized an assortment of strategies. One has been overwhelming force—the deployment of large numbers of conventional forces overseas to destroy terrorist groups and their support networks. This strategy is best illustrated by the large buildup of U.S. and allied military forces in Iraq and Afghanistan after September 11. Another has been a light-footprint approach characterized by a small military presence and a reliance on clandestine law enforcement, intelligence, and special operations forces to help foreign governments dismantle al Qa’ida and to conduct precision targeting.65 As we shall see, a light-footprint approach has been more effective in weakening al Qa’ida and has minimized Muslim radicalization. But U.S. and allied counterterrorism efforts alone do not explain wave patterns.

A second factor is variation in al Qa’ida’s strategy. Terrorist groups have long used attacks to achieve their political goals. Al Qa’ida has sometimes adopted a punishment strategy that involves attacks on civilian populations—a strategy al Qa’ida in Iraq leaders embraced after the U.S. invasion. At other times al Qa’ida leaders have implemented a more selective strategy focused on killing government officials and their collaborators. Over the past two and a half decades, al Qa’ida has lost considerable support when it has adopted a punishment strategy, especially when it has killed Muslims.

A third factor is the ability of local governments to establish basic law and order in their territory when faced with an al Qa’ida presence. Al Qa’ida has established safe havens in countries with a support base of sympathizers and financially, organizationally, and politically weak central governments. Some governments, such as the Taliban in Afghanistan, have actively supported al Qa’ida. Others have tried to counter the group, but their security forces have been too weak or corrupt, as in Yemen. Still others have been effective, as Pakistan was in the aftermath of September 11, when several al Qa’ida leaders were captured in Pakistani cities with the cooperation of the United States. The Arab Spring, popular uprisings that led to the collapse of several North African and Middle Eastern regimes beginning in 2011, was a welcome sign for those fighting for democracy. But it also undermined stability and eroded the strength of several governments, providing an opportunity for al Qa’ida to establish a foothold.

As the past two and a half decades illustrate, there is no single recipe for defeating al Qa’ida. Its organizational structure, strategies, and tactics have evolved over time and in different countries, indicating that counterterrorism efforts must adapt to changing conditions within al Qa’ida sanctuaries. Yet terrorism waves have frequently ebbed when the U.S. and other foreign powers have utilized a light-footprint strategy focusing on clandestine activity, al Qa’ida has embraced a punishment strategy that kills civilians and undermines its support base, and local governments have developed effective police and other security agencies.

Our story begins on the front lines of Sudan, Afghanistan, and Pakistan, where individuals such as Osama bin Laden and Ayman al-Zawahiri prepared for their apocalyptic showdown with the West. From the beginning, however, they faced withering criticism from within the Islamic community about their support of violence. Khartoum would be their first test.