Al Qa’ida in Pakistan

THE MANHUNT FOR Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, one of the masterminds of the September 11 attacks, grew hot in Pakistan in 2003. U.S. intelligence agencies had been desperate to find the al Qa’ida leader, whom colleagues referred to by his code name, Mukhtar. Agents had been contacting every imaginable human source and culling through huge caches of signals intelligence. Just after the September 11 attacks, George Tenet had urged his staff to move outside their comfort zones. “All the rules have changed,” he warned in a memo titled “We’re at War.” “Each person must assume an unprecedented degree of personal responsibility.”1 U.S. and Pakistani intelligence agents had mapped out a network of contacts close to Khalid Sheikh Mohammad, yet they still lacked enough information to capture him.

The situation changed early in 2003. The hunt centered on Rawalpindi, a bustling Pakistani city of nearly 1.7 million located on the Potwar Plateau, 9 miles southwest of Islamabad, the nation’s capital. Rawalpindi lies along the ancient trade routes that connected Persia and the Central Asian steppes to India. Sikhs settled the area in 1765 and invited nearby traders to take up residence as well. It became a strategic military outpost after the British occupied the Punjab in 1849. The old parts of Rawalpindi boast densely packed houses decorated with intricate woodwork and cut brick corbels, with narrow streets that open up into a series of bazaars. The city also has a tradition of sheltering fugitives. Early in the nineteenth century, Shah Shuja, the exiled king of Afghanistan, fled to Rawalpindi after he was deposed by Mahmud Shah. Rawalpindi was an ideal place for al Qa’ida terrorists to hide.

On February 28, 2003, Pakistani intelligence received a tip that an associate of Khalid Sheikh Mohammed who was willing to assist in his capture was arriving at Islamabad International Airport. The informant was scheduled to meet Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, or KSM, as U.S. operatives referred to him, that night in a house on Peshawar Road. Khalid Sheikh Mohammed was the opposite of the pious al Qa’ida militant exemplified by Ayman al-Zawahiri and Osama bin Laden. He had thick black hair, brown eyes, and a plump physique, and he led a lavish lifestyle. While in the Philippines in late 1994 and early 1995, he apparently attended a number of parties where alcohol was consumed and he spent generously on women, frequenting go-go bars and karaoke clubs in Manila. He reportedly gave large tips. He also purportedly buzzed a tower with a rented helicopter to impress a female dentist he was dating.

Yet Khalid Sheikh Mohammed was involved in some of al Qa’ida’s most notorious terrorist attacks and plots, from the September 11 attacks to the 2002 Bali bombings and the assassination of the Wall Street Journal’s Daniel Pearl. “I decapitated with my blessed right hand,” he bragged, “the head of the American Jew, Daniel Pearl, in the city of Karachi, Pakistan.”2 Some intelligence analysts dubbed him the Forrest Gump of terrorists. CIA reporting had indicated that he was “the driving force behind the 11 September attacks as well as several subsequent plots against U.S. and Western targets worldwide.”3

Sensing that the capture of Khalid Sheikh Mohammed was imminent, Marty Martin, who was at the CIA’s Counterterrorist Center, pulled aside George Tenet late on the afternoon of February 28. “Boss, where are you going to be this weekend?” he asked. “Stay in touch. I just might get some good news.”4

Then came the information they needed.

“I am with KSM,” the informant said in a text message, after slipping into a bathroom in the squat two-story white house in Rawalpindi.5

The Pakistanis and Americans shifted into overdrive. At 4:45 a.m. on March 1, they surrounded the home of Ahmed Abdul Qudoos, a pale, white-bearded man who was a member of the Pakistani Islamic political party Jamaat-e-Islami. Pakistani forces broke down the front door and rushed in, brandishing weapons and shouting. In one of the rooms, a man on the ground floor pointed upward. “They are up there,” he yelled.6

Pakistani forces dashed upstairs and found Khalid Sheikh Mohammed and several accomplices, including Mustafa al-Hawsawi, a Saudi member of al Qa’ida who had helped organize and finance the September 11 attacks. KSM quickly grabbed his Kalashnikov; a Pakistani agent tried to wrestle it from him, but the gun went off, shooting the agent in the foot. Before Khalid Sheikh Mohammed and Mustafa al-Hawsawi could do further damage, they were overpowered, hooded, bound, hustled from the house, placed in a vehicle, and quickly driven away, as was Ahmed Abdul Qudoos.

Tenet’s phone soon rang, waking him up. It was Marty Martin. “Boss,” he said, “we got KSM.”7

The capture of Khalid Sheikh Mohammed was a major intelligence victory. Despite the billions of dollars the United States had spent on technical intelligence, it was old-fashioned human intelligence that secured the target. This is what Hank Crumpton had been preaching. “Distance and remote technology may reduce physical risk and protect our consciences, but we lose the tactile sense of the human battlefield,” he had warned.8 The informant, who was “a little guy who looked like a farmer,” according to one American official who met him, was attracted by the $25 million bounty on Khalid Sheikh Mohammed’s head.9 He was duly rewarded.

Sometime later Tenet congratulated him in person. The informant wore one of his best suits, which was neatly pressed, to the meeting. “Do you think President Bush knows of my role in this capture?” he asked Tenet, somewhat innocently.

“Yes, he does,” Tenet replied, “because I told him.”

“Does he know my name?” the informant asked.

“No,” Tenet answered. “Because that is a secret that he doesn’t need to know.”10

Movement into Pakistan

After the Taliban was overthrown, al Qa’ida operatives fled en masse to Pakistan. “The movement of al Qa’ida fighters into Pakistan came in waves,” noted Robert Grenier, the CIA’s station chief in Islamabad.11

A polished operator, always impeccably dressed, Grenier was a passionate Boston Red Sox fan who had a bachelor’s degree in philosophy from Dartmouth College. His aura in the CIA community grew after the September 11 attacks, when he engaged in face-to-face discussions with Mullah Osmani, the deputy of Taliban leader Mullah Omar, in the mountains of Baluchistan Province in Pakistan. After Osmani declined to help the CIA by handing over bin Laden, Grenier had another idea. Would he help overthrow Mullah Omar? As Grenier explained, Osmani “could secure Kandahar with his corps, seize the radio station there, and put out a message that the al Qa’ida Arabs were no friends of the Afghans and had brought nothing but harm to the country and that Bin Laden must be seized and turned over immediately.”12 It would have been a bold move, but Osmani declined.

Fortunately, the Pakistani government was more supportive. On the morning after the September 11 attacks, the U.S. ambassador to Pakistan, Wendy Chamberlin, went to see Pakistan’s president, Pervez Musharraf. She had been sent to pose a question asked by President Bush: “Are you with us or against us?” The meeting, which took place in one of Musharraf’s Islamabad offices, was tense. America was reeling from the events of the preceding day, and President Bush wanted a quick answer from Musharraf. After an hour, Musharraf appeared to be waffling on his commitment to the United States, so Chamberlin resorted to a bit of Hollywood drama. Sitting close to him, she half turned away and looked down at the floor in a display of exasperation.

“What’s wrong, Wendy?” he asked.

“Frankly, General Musharraf,” she responded, “you are not giving me the answer I need to give my president.”

Musharraf quickly replied, “We’ll support you unstintingly.”13

They agreed to discuss more details on September 15. On that day, Chamberlin presented a series of discussion points. One of the most important was capturing al Qa’ida operatives streaming into Pakistan from Afghanistan.

Musharraf had his own negotiating points. “We want you to pressure the Indians to resolve the Kashmir dispute in our favor,” he said.

“We can’t do that,” Chamberlin responded. “This is about the terrorists who attacked America on our soil and not about Kashmir.”

Musharraf was not finished. “We’d also like you to ensure that U.S. aircraft do not use bases in India for operations in Afghanistan,” he insisted.14

His request was not altogether surprising. Pakistan and India had been involved in at least three major wars over the status of Kashmir—in 1947–1948, 1965, and 1971—as well as multiple skirmishes. The most recent border skirmish had, ironically, been initiated by Musharraf in 1999. Pakistani troops and Kashmiri insurgents crossed the Line of Control, which separates Indian- and Pakistani-controlled parts of Jammu and Kashmir, and occupied Indian territory in Kargil. The incident sparked furious artillery clashes, air battles, and costly infantry assaults by Indian troops against dug-in Pakistani forces.15

“We can do that,” Chamberlin told Musharraf. The United States considered Indian bases militarily unnecessary and recognized how provocative their use might be for Pakistan.16

In the end, Musharraf agreed to many of America’s requests. He permitted overflight and landing rights for U.S. military and intelligence units, allowed access to some bases in Pakistan, provided intelligence and immigration information, cut off most logistical support to the Taliban, and broke diplomatic relations with the Taliban.17 The United States used several bases (such as those near Jacobabad, Dalbandin, and Shamsi), set up a joint Pakistani-American facility in the U.S. embassy in Islamabad for coordinating U.S. aircraft flying through Pakistan, and shared intelligence on key Taliban and al Qa’ida leaders.18 The U.S. military also installed radar facilities in Pakistan, which provided extensive coverage of Pakistani airspace.19

Similarly, the United States agreed to many of Musharraf’s requests. U.S. aircraft could not fly over Pakistani nuclear facilities, the U.S. military could not launch attacks into Afghanistan from Pakistan, and the United States would provide economic assistance to the country. These concessions provided a solid foundation for U.S. actions in the fall of 2001 against the Taliban and al Qa’ida. U.S. successes in Afghanistan in 2001, however, had an unpleasant consequence: al Qa’ida forces began to scatter. U.S. intelligence assessments indicated that the bulk of al Qa’ida fighters were flowing into Pakistan’s tribal areas. But many went to such cities as Peshawar and Karachi, while others migrated to Iran.

In December 2001 a U.S. government assessment examined possible al Qa’ida routes from Afghanistan to Pakistan and Iran through several Afghan locations: Konar, Jalalabad, Gardez, Kandahar, and Zaranj.20

Al Qa’ida operatives ended up using all of them. In a meeting in Kandahar that month, al Qa’ida leaders who had remained in southern Afghanistan, led by Saif al-Adel, instructed a group of roughly five hundred fighters to go to Pakistan through Afghanistan’s eastern Paktia Province, near Gardez. They were mainly Arabs, although a smaller number were Uzbeks and Tajiks. Some were temporarily housed in the city of Zormat, while others fled to the Zormat Mountains and then continued into Pakistan.

Figure 4: U.S. Assessment of Potential al Qa’ida Routes

The Management Council

Others fled to Iran and formed al Qa’ida’s “Management Council,” a group of senior officials who supported Osama bin Laden and other leaders in Pakistan. They included Abu al-Khayr al-Masri, Abu Muhammad al-Masri, Saif al-Adel, Sulayman Abu Ghayth, and Abu Hafs al-Mauritani. The exodus of some al Qa’ida members to Iran posed a particular problem for the United States. There was no U.S. military and intelligence presence in Iran, at least not overtly, and the United States had an openly adversarial relationship with the Iranian government. Grenier told CIA headquarters, “Many al Qa’ida fighters were trying to get to Iran. They were interested in temporarily settling in Iran, or else moving on to Gulf states or other sanctuaries. They didn’t want to stay in Pakistan because the government was cooperating with the United States.”21 While the Shi’ite Iranian leadership was generally opposed to Sunni al Qa’ida militants, Iranian officials, motivated by the old adage “my enemy’s enemy is my friend,” provided some aid to anti-American groups.

The Iranian government considered the U.S. presence in neighboring Afghanistan a threat to its security. Iranian intelligence officials soon initiated a meeting with al Qa’ida leaders. Ramzi bin al-Shibh, who was at a December 2001 meeting, reported that Iranian officials expressed their willingness to allow transit and give shelter to some members of al Qa’ida, though under tight scrutiny.22 Beginning in late 2001, Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps Qods Force, whose mission is to organize, train, equip, and finance foreign Islamic revolutionary movements, sheltered over two dozen al Qa’ida members in hotels and private residences.

But in 2002, Iran’s intelligence agency, the Ministry of Intelligence and Security, took charge of relations with al Qa’ida and began rounding up operatives and their families in such cities as Zahedan. Early in 2003, Iran seized members of the Management Council and as many as sixty leaders and associates who had sought refuge there after September 11. Most al Qa’ida leaders and their families were placed under house arrest in crowded conditions. In several instances al Qa’ida prisoners, including women and children, complained to Iranian officials about their conditions and staged protests. In 2003, Osama bin Laden apparently sent a letter to Tehran threatening attacks if al Qa’ida leaders and his own family members were not released. But Iran did not comply and bin Laden did not follow through with the attacks.

Saif al-Adel, who was a member of al Qa’ida’s inner shura, had escaped to Iran through Afghanistan’s western border.23 Like most other al Qa’ida leaders in Iran, Adel was placed under house arrest, though he retained access to the Internet and telephones. Using money provided by wealthy donors from the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, and Kuwait, Adel rented apartments in Iran for some al Qa’ida members and their families. He also reestablished contact with the al Qa’ida leadership and began to organize groups of fighters to return to Afghanistan and support the overthrow of the Karzai regime. In 2003, according to Saudi and U.S. officials, Adel was in communication with the al Qa’ida cell in Saudi Arabia that carried out bombings in Riyadh on May 12.24 He was also in touch with the Arabic-language newspaper Al-Sharq al-Awsat and told it that he believed around 350 “Afghan Arabs” had been killed in Afghanistan since the U.S. invasion and around 180 had been captured. He contributed articles to Mu’askar al-Battar, a jihadist magazine published under the auspices of al Qa’ida’s affiliate in the Arabian Peninsula.25

Sa’ad bin Laden, the third of bin Laden’s sons, and Abu Mus’ab al-Zarqawi, the future leader of al Qa’ida in Iraq, also fled to Iran, as did a handful of other al Qa’ida fighters. Sa’ad bin Laden had developed a close relationship with his father. From Iran he continued to assist al Qa’ida, apparently helping with the truck bombing of a synagogue in Djerba, Tunisia.26

Back at the CIA’s Counterterrorism Center, Philip Mudd and other senior officials were concerned that al Qa’ida leaders were in Iran. Al Qa’ida and Iran did not like each other, Mudd believed, and they certainly didn’t share a common ideological view. But their mutual support did not help the United States. Al Qa’ida leaders didn’t like the situation either, but they didn’t have a better option. If they staged an attack against Iran, some of their leaders might be executed. For Iranian officials such as Ahmad Vahidi, a commander in the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps and later minister of defense, holding and monitoring several al Qa’ida leaders was a wild card.27 Iran could provide them with a safe haven from their bitter enemy, the United States. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill had used similar logic when he declared to his personal secretary, John Colville, that “if Hitler invaded Hell, I would make at least a favorable reference to the devil in the House of Commons.”28

Pakistan’s Struggles

Most al Qa’ida leaders, however, went to Pakistan. In cooperation with the United States, the Pakistani government deployed units from the regular army, Special Services Group, Frontier Corps, and Directorate for Inter-Services Intelligence to conduct operations along routes from Afghanistan to Pakistan. Two brigades of infantry forces from the Ninth Division of the XI Corps were deployed for border and internal security operations for much of 2001 and 2002. Pakistan also established two quick reaction forces from the Special Services Group to provide local commanders with the ability to deploy troops quickly. In addition, approximately four thousand Frontier Corps forces were used to conduct operations in Pakistan’s Federally Administered Tribal Areas.29

In October 2001, Frontier Corps forces clashed with militants crossing the border around Nawa Pass in Bajaur Agency, one of the tribal districts. In December 2001, Pakistan deployed a mixture of forces to Khyber and Kurram Agencies during U.S. operations at Tora Bora and helped capture a small number of al Qa’ida and other foreign fighters.30 Early in 2002, Pakistan increased force levels in North and South Waziristan to target militants during Operation Anaconda. In May, Pakistani forces raided a suspected weapons cache in North Waziristan, netting mortar rounds, antipersonnel mines, and ammunition. The next month soldiers from the Special Services Group, Frontier Corps, and Pakistan’s regular army conducted an assault against al Qa’ida operatives during Operation Kazha Punga in South Waziristan. Pakistani troops entered Khyber and Kurram Agencies to capture al Qa’ida fighters coming from Afghanistan.31

The United States viewed these initial Pakistani military operations as a limited success, even though Pakistan allowed Taliban leaders to establish a sanctuary in Baluchistan Province. Over the course of 2002, Pakistan’s security agencies picked up thousands of militants, though many were eventually released.32 In some cases the militants were released at the cutoff period for detention under the Maintenance of Public Order law or by the relevant courts on bail. Despite these drawbacks, Pakistan played a role in achieving one of the most significant objectives: the overthrow of the Taliban regime. “Musharraf became an international hero,” remarked Ambassador Chamberlin. “Money was flowing into Pakistan. And Pakistan was no longer a pariah state. The situation was euphoric. Musharraf was on the cover of every magazine and newspaper.”33

Yet these large conventional operations netted few major al Qa’ida figures. As President Musharraf later acknowledged, Pakistan’s military forces could not “control a border belt which is so mountainous, treacherous,” and facilitated al Qa’ida’s movement into Pakistan. “They went in unnoticed,” he remarked, “and they went into the cities.”34 The challenge was clear. Large numbers of conventional military forces like those deployed by Pakistan could not win this shadow war. Instead the hunt required lethal clandestine operations from agencies that could operate with speed and stealth in rural and urban areas. It was a mission better suited for police, intelligence units, and special operations forces.

The Manhunt Begins

While al Qa’ida fighters slipped into Pakistan, a clandestine manhunt began across the country’s settled areas. One of the first major captures was Abu Zubaydah, who was born on March 12, 1971, to Palestinian parents in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.35 His six-volume diary, which was seized when he was captured in 2002, revealed a troubled childhood. Zubaydah was rejected by colleges in Saudi Arabia, Egypt, the Philippines, and the United States before he entered a program in New Delhi. Homesick and dejected, he struggled to find direction, writing that “a Palestinian is born in a country not his [and] has to coexist in a country whose citizens first look toward him as one of a displaced people. Their looks sometimes speak out and hurt you.”36 Zubaydah recounted painful experiences of prejudice and rejection associated with his Palestinian heritage. He also suffered from bouts of loneliness.

His biggest struggle was with his father, a schoolteacher and administrator. Zubaydah wanted to please his father but also wanted to establish his own identity. “I simply believe in my independence from everything, even from my father,” he wrote. “Aren’t you going to finish your medical school to please your Dad?” he queried, somewhat rhetorically, in another entry. “Well, I decided to get my martyrdom certificate instead. I do not think my father will be happy about it.”37

Zubaydah turned to jihad. With a neatly trimmed black beard and spectacles, he looked more like a graduate student than a terrorist. He first traveled to Afghanistan to participate in the anti-Soviet war in 1990, feeling that this would bring him closer to God. After mingling with the radicalized contingent of foreign fighters, he became obsessed with destroying Israel and the United States. His initial request to join al Qa’ida in 1993 was rejected, apparently because he was a “generalist” and al Qa’ida leaders were looking for someone with “niche skills.”38 But he was obstinate. He received a shrapnel wound to the head in the early 1990s while fighting on the front lines in Afghanistan, a testament to his commitment to jihad.

Over the next decade Zubaydah became one of the most ruthless international terrorists, with a close connection to senior al Qa’ida officials. Though not a formal member of al Qa’ida, he developed a personal relationship with Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, Ayman al-Zawahiri, Abu Mus’ab al-Zarqawi, and even Osama bin Laden. In the late 1990s he played a role in the millennium plots, including the plans to bomb Radisson hotels in Amman, Jordan, and three other sites. On November 30, 1999, Jordanian intelligence intercepted a call between Abu Zubaydah and Khadr Abu Hoshar, a Palestinian militant, and determined that an attack was imminent; Jordanian police arrested twenty-two conspirators and foiled the attack. Abu Zubaydah was sentenced to death in absentia by a Jordanian court for his role in the plots. He also developed a relationship with Ahmed Ressam, who was captured in December 1999 at the U.S.-Canadian border in Port Angeles, Washington, and later convicted of planning to bomb the Los Angeles International Airport on New Year’s Eve. Ressam had stayed at Zubaydah’s guesthouse in Islamabad in January of that year.39

By 2001, Zubaydah was running several training camps and guesthouses for foreign fighters in Afghanistan, including the Khaldan training camp near Khowst Province, as well as a series of guesthouses in Pakistan, primarily in Islamabad.40 The guesthouses were used as temporary residences by foreign fighters on their way to—or back from—the Khaldan camp. Khaldan was not under the control of al Qa’ida, though Zubaydah knew many of the members. He pulled the plug around April 2000, not long after bin Laden told him that “it would be better if Khaldan camp remains closed.”41 Bin Laden wanted to unify the unwieldy network of foreign fighters operating in Afghanistan under his umbrella.

But Zubaydah kept popping up in U.S. and British intelligence reports. On May 30, 2001, senior CIA officials, led by George Tenet, briefed Condoleezza Rice that Zubaydah was working on a number of attack plans, some of which appeared to be close to execution. In June, British intelligence briefed the CIA that Zubaydah was planning suicide car bomb attacks against U.S. military targets in Saudi Arabia.42 In August a Presidential Daily Brief entitled “Bin Laden Determined to Strike in U.S.” stated that Zubaydah was in touch with the millennium bomber Ahmed Ressam. “Convicted plotter Ahmed Ressam has told the FBI,” the brief noted, “that he conceived the idea to attack Los Angeles International Airport himself, but that in [REDACTED], Laden lieutenant Abu Zubaydah encouraged him and helped facilitate the operation. Ressam also said that in 1998 Abu Zubaydah was planning his own U.S. attack.”43

On September 11, 2001, Zubaydah was in a safe house in Kabul with a group of foreign fighters watching video footage of the twin towers burning. The group slaughtered several sheep to celebrate the attacks. He went into hiding soon after, as the manhunt for al Qa’ida fighters began. In December he escaped to Karachi, Pakistan, through Afghanistan’s eastern Paktika Province, moving among safe houses and using more than thirty-five aliases. Pakistani and U.S. intelligence agencies began to piece together his movements based on human sources, signals intelligence, interrogations of lower-level operatives, and the clandestine monitoring of e-mails. U.S. intelligence agencies, including the National Security Agency and the Central Intelligence Agency, provided much of the signals intelligence and other technical intelligence by tracking cell and satellite conversations.44

In February 2002, CIA station chief Robert Grenier learned that Zubaydah had frequented thirteen safe houses in three cities: nine in Faisalabad, one in Karachi, and three in Lahore. Armed with one of Zubaydah’s cell phone numbers, the CIA and FBI began tracking his movements. But Zubaydah was careful about security. He turned on his phone only briefly, to collect messages. On a wall at the U.S. embassy in Islamabad, U.S. intelligence officials posted a large blank piece of paper with Abu Zubaydah’s phone number at the center. Over the next several weeks they linked phone numbers and data points from U.S. and Pakistani intelligence files, creating a map of Zubaydah’s social network.45

In the early morning hours of March 28, 2002, Pakistani and American security officials raided all thirteen sites simultaneously. The site in Faisalabad, an industrial city in Punjab Province, was a sizable coffee-colored, two-story building with large pillars at the front door, white trim around the outside windows, and razor wire atop the outer wall—not exactly a rustic cave. The Pakistanis took the lead, breaching the perimeter fence and breaking the reinforced front door with a ramrod. A soldier confronted Zubaydah with an AK-47.46

“The first thing the guy does is, he grabs the barrel of it and tries to wrestle the gun away,” said an FBI official. “This turns out to be Abu Zubaydah. So he is at the other end of the gun. The Pakistani soldier, judging the path of least resistance, he pulls the trigger. So Abu Zubaydah’s pulling the gun, which shoots him in the stomach and groin and puts numerous rounds through him, and he goes down.”47

The CIA suddenly had a bizarre situation. Deciding that Zubaydah could provide useful information on past and future terrorist attacks, the CIA leadership moved to keep him alive. Alvin Bernard “Buzzy” Krongard, the CIA’s executive director, was on the board of directors at Johns Hopkins Medical Center. He arranged for a doctor to fly a CIA-chartered aircraft to Pakistan and save Zubaydah’s life.48

The raid on Zubaydah’s house and the attempt to save his life were both successful. Pakistani authorities captured roughly two dozen al Qa’ida members. The raid—and eventually Zubaydah—provided a wealth of information. First, Zubaydah was captured at a safe house operated by Lashkar-e-Taiba, or Army of the Righteous, a terrorist group established in the 1980s to liberate Indian-controlled Kashmir through violence. Zubaydah’s presence at the safe house indicated that Lashkar members were facilitating the movement of some al Qa’ida members in Pakistan. This discovery was disturbing to some U.S. officials, since Lashkar-e-Taiba had close links with Pakistan’s spy agency, the ISI. Zubaydah frequently used a computer that belonged to Lashkar-e-Taiba in Faisalabad from late 2001 until early 2002.49

Second, several key pieces of intelligence captured at the Faisalabad safe house led to other al Qa’ida operatives. These included two bank cards, one from a bank in Kuwait and another from a bank in Saudi Arabia, as well as Zubaydah’s diary, computer disks, notebooks, and phone numbers. The diary was particularly illuminating and became a rich source of information. In one entry, for example, Zubaydah noted that he was preparing for follow-on attacks within days after September 11. A diary entry in 2002 described plans to wage war in the United States by instigating racial wars, initiating timed explosive devices, attacking gas stations and fuel trucks, and starting timed fires.50 A Saudi captured with Zubaydah, Ghassan al-Sharbi (also known as Abdullah al-Muslim), who was in his early twenties, was planning to hack the New York Stock Exchange.51

Third, Zubaydah provided considerable detail to his FBI and CIA interrogators about al Qa’ida.52 As one CIA report concluded, “Within months of his arrest, Abu Zubaydah provided details about al Qa’ida’s organizational structure, key operatives, and modus operandi. It was also Abu Zubaydah, early in his detention, who identified KSM as the mastermind of the 11 September attacks.”53 Zubaydah provided more intelligence than almost any other operative, telling his interrogators that “brothers who are captured and interrogated are permitted by Allah to provide information when they believe they have ‘reached the limit of their ability to withhold it’ in the face of psychological and physical hardships.”54

“Take Me on Your Journey”

In early 2002, Art Cummings traveled to Guantánamo Bay, Cuba. Located at the southeastern end of the island, Guantánamo Bay boasts a spacious harbor surrounded by verdant hills. In 2002 the U.S. military constructed a detainment camp there for captured al Qa’ida and other terrorists. Cummings had been sent by the FBI to interview U.S. citizens and others involved in plots against the U.S. homeland. He wanted to know why these individuals were radicalizing and fighting the United States.

“Take me on your journey,” he said to one young detainee, “on how you went from college in the United States to the battlefield of Afghanistan.”

The reply stopped Cummings short.

“Well,” the detainee explained, “I had a choice of doing what my parents told me to do: go to college and get a job. Or I could go to Mindanao, shoot rocket-propelled grenades, and blow things up.”

Joining a militant group was exhilarating for a young man. The detainee suddenly had the opportunity to travel to exotic places and take courses in weapons training, learn intelligence skills, and bond with other youths committed to a common cause. Cummings could relate; he had joined the Navy SEALs for similar reasons. Still, he was perplexed.

“What about Islam?” he asked.

“Couching this whole thing in terms of Islam,” the detainee answered, “was what made my parents happy.”

Religion was a secondary motivation for joining the fight.

“But once I joined,” the detainee explained, “I couldn’t get out. If I returned to my native country, they would have arrested me and thrown me into prison.”55

Cummings wanted to understand the detainees’ motivations, but he also needed to collect information on terrorist plots and the al Qa’ida network. His interviews with captured al Qa’ida fighters reinforced his conviction that coercive techniques were generally unnecessary and often counterproductive. He argued that what drove some terrorists to talk was forcing them to ponder their future.

“You understand, you’re going to die in this steel box,” Cummings told several of them. “And when you’re dead, your life is nothing. You will die, and you will be nothing to anyone. When you die, you will be in an unmarked grave, and no one will know how you died, when you died, or where you’re buried.”

For others, it was manipulating basic human needs. “Eventually these guys just get tired of living in austere conditions, and the government offers them different accommodations based on different levels of cooperation,” said Cummings.

One detainee was blunt. “He saw a little snuff on my lip,” explained Cummings. “He asked for some, so I said, ‘Sure.’ I gave him some.”

The doctors at Guantánamo Bay were outraged.

“Okay,” Cummings replied, “enlighten me here. What’s the problem?”

“Well, it’s not healthy,” one doctor lectured him.

“The only reason he’s talking to me is because I’m supplying him with snuff,” Cummings retorted. “So I’m going to be bringing a tin of Copenhagen every time I interrogate this guy. And I guarantee you that every time before he starts talking, he’s going to put a big ol’ mighty healthy dip in his lip.”56

Cummings’s concern about coercive techniques spoke to a much broader debate within the U.S. government and across the American public. In a letter to President Bush in December 2002, for example, Human Rights Watch executive director Kenneth Roth said that he was “deeply concerned by allegations of torture and other mistreatment of suspected al-Qaeda detainees.”57 Human Rights Watch reported that eleven suspects, including Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, had “disappeared” in secret prisons and might have been tortured under the direction of the CIA.58 A 2005 U.S. Justice Department memo stated that Khalid Sheikh Mohammed had been waterboarded 183 times and Abu Zubaydah 83 times. The memo concluded that the “CIA used the waterboard extensively in the interrogation of KSM and Zubaydah, but did so only after it became clear that standard interrogation techniques were not working.”59

The reality was complicated. In a few instances, as with Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, coercive measures appeared to provide some information on homeland plots. But whether these techniques were necessary is unclear, and determining that would require proving the counterfactual argument that more traditional techniques could have been as effective. The divide was particularly acute between some CIA officials, who insisted that coercive measures were necessary and effective, and many FBI officials, who asserted that they were counterproductive.60 In the vast majority of cases, coercive techniques appeared to be unnecessary and al Qa’ida operatives provided information in response to more traditional interrogation techniques.

Despite the controversy, the interrogation of al Qa’ida detainees and, more important, the capture of millions of documents and other information from raids led to additional arrests. “High and medium value detainees have given us a wealth of useful . . . information on al-Qa’ida members and associates,” concluded one CIA assessment, “including new details on the personalities and activities of known terrorists.”61 The CIA took pride in the fact that “the intelligence acquired from these interrogations has been a key reason why al Qa’ida has failed to launch a spectacular attack in the West since 11 September 2001.”62 Detainee interrogations were a critical source of human intelligence. In 2004, for instance, the CIA counted a total of 6,600 human intelligence reports on al Qa’ida, half of which were from detainee reporting.63

As the debate raged on, however, al Qa’ida members continued to fall.

Falling Dominoes

Born on May 1, 1972, in Yemen, Ramzi bin al-Shibh grew up in a working-class neighborhood in Sana’a, the capital city. Sana’a is situated at the foot of Mount Nuqum, at an elevation of more than 7,200 feet above sea level, in the western part of the country. For centuries it has been the chief economic, political, and religious center of the Yemen Highlands. In 1987, bin al-Shibh’s father died and his mother and older brother, Ahmed, looked after him. In 1987, while still in high school, he worked as a part-time clerk for the International Bank of Yemen. While he first became a devoted Muslim, at the age of twelve, he did not appear to be radical.64 A childhood friend described him as “religious, but not too religious.”65

Bin al-Shibh first attempted to leave Yemen in 1995, when he submitted an application for a U.S. visa but was rejected. He then went to Germany, applying for asylum under the name Ramzi Omar. In Hamburg he met Mohammed Atta, who became the lead al Qa’ida operative in the United States, coordinating the attacks with bin al-Shibh.66 The two became close friends, and bin al-Shibh began to show signs of radicalization. He increasingly complained about a “Jewish world conspiracy” and argued that the most important duty of every Muslim was to pursue jihad.67 By 1998, bin al-Shibh and Atta shared an apartment in the Harburg section of Hamburg and had begun to associate with two other September 11 hijackers, Marwan al-Shehhi and Ziad Jarrah. By that time bin al-Shibh was wiry, with recessed eye sockets, black hair, and a scraggly beard. He often wore a white and red kaffiyeh, or headscarf, typical of Yemeni men. Friends and acquaintances described him as charismatic and self-confident.

“His philosophy, even his vocabulary, is very much like bin Laden’s,” remarked Yosri Fouda, an Al Jazeera reporter who interviewed him. “He also has the sheikh’s serene charm, zest, and religious knowledge.”68

In late 1999, bin al-Shibh traveled with Atta, al-Shehhi, and Jarrah to Kandahar, where they were trained at al Qa’ida camps. The four met Osama bin Laden and pledged bayat, or loyalty, to him. They also accepted his proposal to martyr themselves in an operation against the United States.69 “I swear allegiance to you,” they repeated, “to listen and obey, in good times and bad, and to accept the consequences myself. I swear allegiance to you, for jihad and hijrah, and to listen and obey. I swear allegiance to you, to listen and obey, and to die in the cause of God.”70

As bin al-Shibh later acknowledged, bin Laden was an alluring figure, revered by al Qa’ida members. He generally had a calm demeanor, even during stressful situations, and was viewed as a pious Muslim. Bin Laden was humble and talked to those around him with a sincere and respectful demeanor. He rarely talked down to people, and he interacted with fighters from all levels of al Qa’ida, sharing meals with the lowest-level foot soldiers. He listened carefully. When discussing the tactics of an operation, for example, bin Laden would consider the opinions of everyone involved, giving each person his attention.71 But when he made up his mind, he could be myopic and bullheaded. As his son Omar recalled, “His stubbornness had brought him many problems. Once he wished for something, he never gave up.”72

Bin al-Shibh was apparently chosen to be one of the September 11 hijackers and traveled with Atta to Karachi at the end of 1999 to meet with Khalid Sheikh Mohammed and discuss the plot in more detail.73 He returned to Germany early in 2000. Bin al-Shibh attempted to obtain a U.S. visa to attend flight school on four occasions from May to November of that year. But the U.S. Department of State rejected each application.74 He was apparently so desperate to get into the United States that he e-mailed a U.S. citizen in San Diego and asked her to marry him, but that failed as well.75

In the eight months before the attacks, bin al-Shibh was the primary intermediary between the hijackers in the United States and al Qa’ida leaders in Afghanistan. He relayed orders from al Qa’ida operatives to Atta via e-mail or phone and met with Atta in Germany in January 2001 and in Spain in July 2001 to discuss the operation’s progress.76 The CIA made it clear that “Ramzi Bin al-Shibh, not KSM, was in direct contact with the 11 September hijackers once they were in the United States.”77

In August 2001, Mohammed Atta and bin al-Shibh discussed the impending attacks via e-mail. Atta pretended that he was a young man in the United States talking to Jenny, his girlfriend in Germany.

“The first semester starts in three weeks,” he wrote to bin al-Shibh. “Nothing has changed. Everything is fine. There are good signs and encouraging ideas. Two high schools and two universities. Everything is going according to plan. This summer will surely be hot. I would like to talk to you about a few details. Nineteen certificates for private study and four exams. Regards to the professor. Goodbye.”78

As U.S. intelligence officials later realized, the four schools meant the intended targets in the United States and the “nineteen certificates” indicated the nineteen hijackers. A week before the attacks, bin al-Shibh left Germany and arrived in Afghanistan, where he soon celebrated what he called the “Holy Tuesday Operation.” After the U.S. bombing campaign began in the wake of the attack, he fled Afghanistan and spent about six weeks in Iran. In early 2002, bin al-Shibh traveled to Karachi and began working with Khalid Sheikh Mohammed on follow-on plots against the West, including an attack against London’s Heathrow Airport.79 The plot involved hijacking two aircraft from Heathrow and crashing them into the terminal buildings. He also worked on a manuscript justifying the September 11 attacks, titled “The Truth About the New Crusade: A Ruling on the Killing of Women and Children of the Non-Believers.” It was a rambling document that tried to justify civilian casualties.

“Someone might say that it is the innocent, the elderly, the women, and the children who are victims, so how can these operations be legitimate according to sharia?” bin al-Shibh asked rhetorically. “They are legally legitimate,” he answered, “because they are committed against a country at war with us, and the people in that country are combatants.”80

As the manhunt for al Qa’ida leaders in Pakistan intensified in 2002, bin al-Shibh grew increasingly wary about personal security. During an interview with journalist Yosri Fouda, he became incensed when he discovered that Fouda had brought along his mobile phone. Bin al-Shibh grabbed the phone from him, removed the SIM card and battery, and placed it in another room to ensure that U.S. and Pakistani officials couldn’t track it.81

He was right to be worried. Much as with Khalid Sheikh Mohammed and Abu Zubaydah, patient intelligence analysis by Pakistani and American operatives—using human sources, intercepts, and information collected from other raids—paid off. The U.S. interrogation of Abu Zubaydah provided critical information on bin al-Shibh’s travel patterns and associates.82 But the biggest break came on September 10, 2002, when ISI officers detained Mohammad Ahmad Ghulum Rabanni, an al Qa’ida operative and Pakistani citizen, along with his driver. During interrogations that day, they provided information about al Qa’ida safe houses in Karachi, including the one where bin al-Shibh was hiding.

Pakistani forces moved quickly. In the early morning hours of September 11, 2002—one year after the attacks in New York City and Washington—Pakistani ISI officers, Army Rangers, and police conducted raids of three suspected al Qa’ida residences in two sections of Karachi. The first safe house was located on Tariq Road in the Pakistan Employees Cooperative Housing Society area, an affluent section of the city, home to nearly one million people. When Pakistani forces began the raid, three individuals present, including Ramzi bin al-Shibh, held knives to their throats and threatened to kill themselves rather than be taken into custody. The standoff lasted four hours before Pakistani officers overpowered and seized them.83 Pakistani and U.S. officials discovered a wealth of information when they combed through the safe house, including high explosives, nearly two dozen remote radio detonators, individually wrapped documents belonging to various members of Osama bin Laden’s family, a handwritten note to a senior al Qa’ida operative, identification cards for Ahmad Ibrahim al-Haznawi (a September 11 hijacker), and contact information for several known al Qa’ida operatives.84

The two other safe houses were located in the defense II commercial area of Karachi. ISI officers had information that six to eight al Qa’ida operatives who were part of a special terrorist team deployed to attack targets in the city were staying there. Preparing for the worst, the ISI called in backup. The raid began around 10 a.m. on September 11, and a two-and-a-half-hour firefight ensued between al Qa’ida fighters and Pakistani security forces. The terrorists, who were mostly Arabs, threw four hand grenades and fired hundreds of rounds at Pakistani forces, who returned fire. Two Arabs were killed, five were captured, and several ISI operatives, police, and Rangers were injured. During a search of the safe houses in this area, Pakistani authorities seized a laptop computer that contained a variety of manuals and files describing al Qa’ida ideology and tactics.85

As with other captures, intelligence collected at the three safe houses was critical in tracking down al Qa’ida operatives. Bin al-Shibh led to Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, who was seized on March 1, 2003. Not all Pakistanis supported their government’s decision to deliver him, or any al Qa’ida fighters, to the United States, however. One Pakistani newspaper published an article called “FBIistan,” complaining about the raid and saying that if “any foreign person has committed a crime in Pakistan, he should be tried under the law of the land. But we have been playing the role of a mercenary for the United States.”86 Musharraf’s government ignored these objections, however, and continued to cooperate with the United States, receiving millions of dollars in reward money. The press continued to prove nettlesome to counterterrorism operatives: on March 2, 2003, some media outlets showed photos of Khalid Sheikh Mohammed as a suave and dashing fighter, painting him as al Qa’ida’s James Bond. Marty Martin from the Counterterrorism Center phoned George Tenet. “Boss,” Martin noted in palpable disgust, “this ain’t right. The media are making the bum look like a hero. That ain’t right. You should see the way this bird looked when we took him down. I want to show the world what terrorists look like.”87

CIA officers on the scene of Khalid Sheikh Mohammed’s arrest had taken digital pictures of him and sent them back to CIA headquarters. Tenet suggested that Martin and Bill Harlow, the CIA’s spokesman, look through the photos. They found the most evocative one, and Bill called an Associated Press reporter and told him, “I’m about to make your day.”88 The photo showed a disheveled Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, moments after the capture, still groggy from being awakened in the middle of the night and dragged out of his house. It was not a good hair day. He had bloodshot eyes, day-old stubble, and a sizable mat of chest hair showing under his grimy white T-shirt.

His capture produced a trove of new intelligence. U.S. and Pakistani officials seized a hard drive that had information about the four airplanes hijacked on September 11, including code names, airline companies, flight numbers, and names of the hijackers. It also had transcripts of chat sessions belonging to at least one of the September 11 hijackers, three letters from Osama bin Laden, spreadsheets that described financial assistance to families of known al Qa’ida operatives, a letter to the United Arab Emirates threatening attack if that country’s government continued to help the United States, and a document summarizing operational procedures and training requirements of an al Qa’ida cell.89 The CIA’s interrogation of Khalid Sheikh Mohammed was also useful, shedding light on al Qa’ida’s strategic doctrine, plots, key operatives, and probable methods of attacks on the U.S. homeland.90

Other dominoes began to fall. Khalid Sheikh Mohammed provided critical information that aided in the 2003 capture of Majid Khan, an al Qa’ida official who was involved in planning multiple attacks in the United States.91 In an example of how information from one detainee can be used in debriefing another, Khalid Sheikh Mohammed detailed Majid Khan’s role in delivering $50,000 in December 2002 to operatives associated with Hambali, the military leader of the Indonesian terrorist organization Jemaah Islamiyah. U.S. officials then confronted Majid Khan with this information, and he acknowledged that he had delivered the money to an al Qa’ida and Jemaah Islamiya operative named Mohd Farik bin Amin, better known as Zubair.92 Khan provided Zubair’s physical description and contact number.93 Because of that information, Zubair was captured in June 2003.94 In addition, Khalid Sheikh Mohammed led the CIA and FBI in August 2003 to Hambali, who was hiding in Thailand. Hambali had developed a close relationship with al Qa’ida operatives and was intimately involved in the 2002 terrorist attack in Bali, which killed more than two hundred tourists.95

A Laughingstock

Al Qa’ida leaders were now under intense pressure in Pakistan. U.S. intelligence agencies, including the CIA and the FBI, were sharing information and coordinating efforts better than they had before September 11. The relationship wasn’t perfect, but it had improved. The director of the Counterterrorist Center chaired a meeting each evening that included CIA officers and representatives from other agencies across the U.S. government.96

In this season of success for U.S. and Pakistani forces, al Qa’ida suffered a staggering number of losses. In addition to Abu Zubaydah, Ramzi bin al-Shibh, and Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, dozens of leaders were captured: Abdu Ali al Haji Sharqawi in Karachi in February 2002; Yassir al-Jazeeri in Lahore in March 2003; Mustafa al-Hawsawi in Rawalpindi in March 2003; Walid bin Attash and Ammar al-Baluchi in Karachi in April 2003. Key al Qa’ida leaders were also captured or killed in other countries, including in Thailand, Yemen, Saudi Arabia, and Morocco. Most of these operations, such as the capture of Abd al-Rahim al-Nashiri in 2002, were the result of careful intelligence work, not the use of large-scale military force.

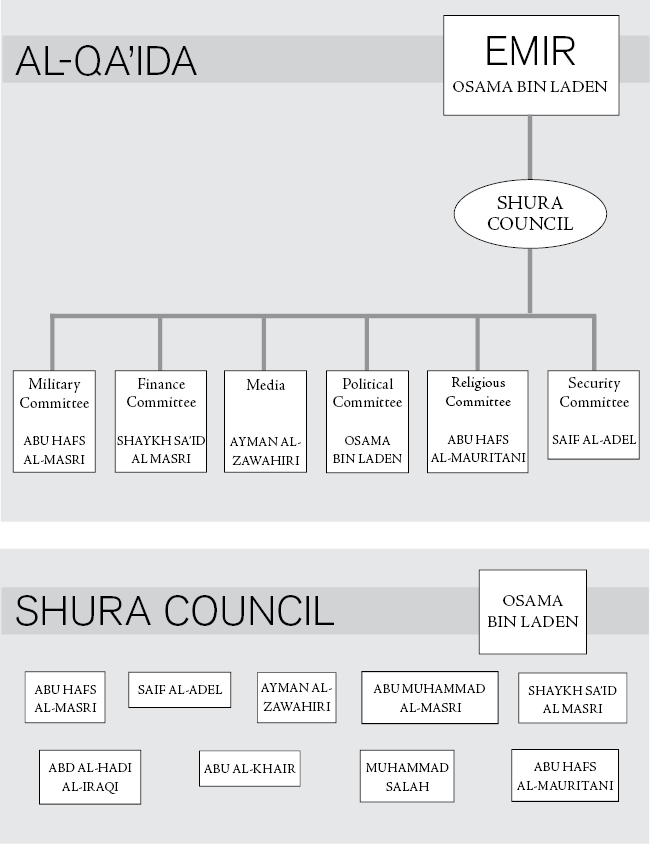

The United States now possessed a more nuanced understanding of its enemies. Al Qa’ida was composed of a shura council and several core committees: military, media, finance, religious, families, documents, radio communications, and external support. It was hierarchically structured, much like a multinational corporation. The shura council was the most powerful committee and served as an advisory body to Osama bin Laden, who acted as its chairman, asking questions and listening to the discussions at hand. The council met regularly, sometimes once a week, to discuss important issues. Key members included Ayman al-Zawahiri, Abu al-Khayr al-Masri, Abu Ghayth al-Kuwaiti, Saif al-Adel, Abu Muhammad al-Masri, Abd al-Hadi al-Iraqi, and Shaykh Sa’id al-Masri.

Figure 5: Al Qa’ida Organizational Structure, 2001

As leader, bin Laden was primarily concerned with the shura council and the military committee, especially its external operations subcommittee. By 2003 some of the shura members, such as Muhammed Atef, had been killed. The rest had fled to Pakistan, Iran, and other locations.

Al Qa’ida’s difficulties were captured in a letter from Saif al-Adel to Khalid Sheikh Mohammed on June 13, 2002. “Today, we are experiencing one setback after another and have gone from misfortune to misfortune,” he wrote. It was embarrassing and made al Qa’ida a “laughingstock of the world.”97

Part of the problem, Adel explained, was bin Laden, who had failed to develop a cogent strategy for what would happen after the September 11 attacks, beyond a general commitment to fight the Americans. On October 2001, bin Laden made at least two public appearances in Khowst Province, noting that while al Qa’ida might lose part of northern Afghanistan, it would surely hold southern Afghanistan. In a message to Mullah Omar on October 3, he remarked that U.S. military operations in Afghanistan would fail. “A campaign against Afghanistan,” bin Laden wrote, “will impose great long-term economic burdens, leading to further economic collapse, which will force America, God willing, to resort to the former Soviet Union’s only option: withdrawal from Afghanistan, disintegration, and contraction.”98

But by 2003 he appeared to have been wrong. Al Qa’ida lost its sanctuary in Afghanistan, and a growing number of members were captured or killed because of clandestine U.S. operators. The reverse wave against al Qa’ida had gained momentum as the United States continued to execute an effective light-footprint strategy led by the CIA, FBI, and special operations forces. Senior al Qa’ida leaders had not planned far enough ahead. They had no real plans for additional attacks against the United States. Bin Laden, Adel complained, continued to pressure other leaders to “attack, attack, attack.” But there was no clear organization, and security concerns made it almost impossible for al Qa’ida leaders to communicate with each other. It was time, he argued, to pull back and reconsider the group’s goals and missions. “I say today we must completely halt all external actions until we sit down and consider the disaster we caused,” he concluded. “My beloved brother, stop all foreign actions, stop sending people to captivity, stop devising new operations, regardless of whether orders come or do not come from [bin Laden].”99

Al Qa’ida leaders had hoped to attack the United States again. But the FBI and other U.S. government agencies, working desperately to prevent another attack on the homeland, now faced their most significant test in the United States.