PART II

THE MANY FACES OF THE SOCIOPATH

The following section represents the results of my interviews with victims and sociopaths, about the behavior of sociopaths in different settings. These chapters deal with: 1) living with a sociopath, 2) having a work and personal relationship with a sociopath, and 3) having a strictly business relationship with a sociopath.

Behavior and Lies

Is the person who behaves like a sociopath really a sociopath? Classically, a sociopath needs the condition diagnosed by a psychiatrist or other mental health practitioner. However, few sociopaths are actually diagnosed this way. Thus, one is left with the characterized behavior patterns and traits and the way others define someone with whom they have had a business or personal relationship or someone who they have just read about or observed in action on news videos. This behavioral approach is the one I have used in selecting people to interview or in citing the stories I have read about or viewed online.

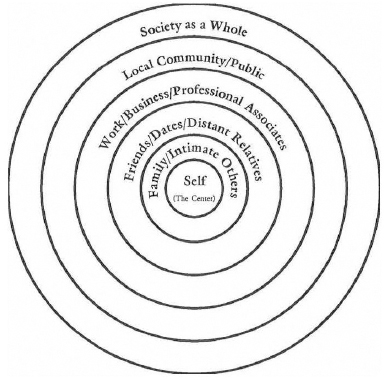

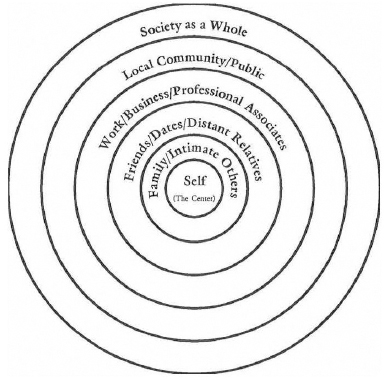

The use of lies creates a protective shield or weapon for attack which sociopaths use, much more often than the average person. I began thinking of the way lies can be used to defend or attack in a variety of situations, ranging from activities in public, at work, and in one’s personal life. These are like zones around the individual which go from the more personal to society as a whole.

An example of these zones of action looks something like this, originally published in my book Making Ethical Choices, Resolving Ethical Dilemmas, now published by Changemakers Publishing.

The nature of the lies may differ, since they are created for different situations in different zones of life. But the overall pattern of behavior is the same.

Certainly, one cannot always be correct in inferring that someone is a sociopath by observing or interacting with them in a very small number of encounters. But one might make a good guess timate of a person’s thoughts, beliefs, feelings or lack of feelings, and intent based on the circumstances. The process is much like what a prosecutor seeks to do in showing if someone has a mens rea, or general or specific intent sufficient to indicate they intended to commit a certain crime, which is defined by having the necessary mens rea to commit it. In the criminal justice system, having a mens rea needs to be brought out by evidence that certain actions or lack of actions reflect a person’s interior thoughts, beliefs, feelings, and attitudes that contribute to this required criminal intent. But people every day draw on their own perceptions beliefs of how and why people act as they do to help facilitate and social relationships, for one has to continually make guesses about people’s meanings based on what they say or how they act. In everyday communication, these guesses become second nature; we don’t think about them and we learn to behave in a way we consider appropriate in response to whatever else the person says or does. By the same token, we may come to judge someone else as behaving normally or like a sociopath, though the sociopath’s skill in wearing a mask can conceal this identity from others.

Behaving Like a Sociopath and the Views of Others

I began thinking about how sociopaths can use lies to support their behaviors in different settings when an associate heading a school told me about a student who sought revenge on another student, and also when I followed the Oscar Pistorius trial online. These were very different settings and stories—but the classic pattern of behaviors commonly engaged in by sociopaths were there in both cases.

In the “less famous” case, a student in a small professional college, let’s call her Jean, harbored a long-term resentment against three other students, Meg, Betty, and Veronica, though outwardly, Jean acted friendly and helpful to the others. Then came the time to take the final test, which was half of the students’ grades, based on entering the answers on a multiple choice answer sheet.

After the test, Meg, Betty, and Veronica thought they did very well, and were surprised when the instructor called them in to tell them they had failed, so they didn’t graduate, because their overall marks weren’t high enough. The instructor was surprised, because the three had been good students, but he felt he couldn’t pass them because of such low grades.

That would have been that, had one student not come forward with the truth. She told the instructor that she had heard another student say that Jean had been bragging about how she was able to go into the instructor’s office, pick up the test answer sheets, and change the three ladies’ answers, so they would be wrong on many questions, and return the answer sheets with the wrong answers. The instructor was flabbergasted, but soon remembered how he had often left the office unlocked for a few minutes, during the times he would go to the rest room or get a snack. After he asked around to see if anyone saw anything unusual, another student said she had observed someone going into and out of his office, but didn’t think much about it at the time. Eventually, the instructor traced back the chain of students to discover two friends of Jean’s who heard her bragging about changing the exam.

At first Jean tried to lie her way out of everything. She talked about only going into the instructor’s office to look for him. She acted surprised that anyone could think she would change exam answers. But the instructor confronted her with the results of his own investigation, which led him to discover a hallway videocam, which showed her proudly proclaiming how easy it was to sneak out the answer sheets to make changes and sneak the test back in again. So clearly Jean was caught and had to confess. Ultimately, she was the one who was suspended, and the instructor invited Meg, Betty, and Veronica to retake the exam, which they all passed, so they could graduate.

Why had Jean done what she did, while outwardly acting like a friend to the three women? As it turned out, she was jealous of their success in school. She imagined if they flunked out, she could be one of the top three students. She felt great pride at seeing them flunk and imagining herself receiving honors on stage during the graduation. So she initially lied to appear that she had no reason to harm the three women, and she lied again to get out of being blamed for their failure, until it became too late to make any more excuses—her real intentions toward her victims were on tape.

Though at the time Jean was never considered a sociopath, her “destroy the enemy” approach to cause the three women to fail the exam and flunk out of school was just how a sociopath would behave—doing whatever is necessary to remove any obstacles to her goal of being in the top three in her class, since she thought that would help her find a job in the field after graduating. She didn’t care about the damage it might do to the three students, so she lied until she was caught and had no way to explain away her lies.

Right around the time I heard her story, I was also following the Oscar Pistorius trial and saw the parallels. In his well-known story, he claims he heard an intruder, got out of bed without checking if his girlfriend was beside him in bed, blasted four shots into the locked bathroom door, killing his girlfriend, and then yelled, sobbed, tried to revive her, and called to get help. Conversely, the prosecutors argued that Pistorius had an argument with his girlfriend, and after she fled into the bathroom to escape his anger, he shot her, and later sought to cover up his actions by claiming it was all a terrible accident.

Was it? Or was Oscar using lies to cover up what happened by claiming he thought he was shooting at an intruder, instead of feeling real guilt for what he had done. In rendering the verdict, the judge concluded that the prosecution couldn’t prove he had the necessary intent—the mens rea—to prove murder, although she found him guilty of culpable homicide for negligently firing the gun into the bathroom door. Yet, without a confession of what he was actually thinking and feeling, how could the prosecutor prove his intent? So for five months, the trial went on, as Pistorius and his defense lawyers sought to convince the jury of his side of the case, while some evidence even suggested that he was taking acting lessons to help him show the proper behavior and emotions to portray his deep grief and guilt for what he had done.

Yet, while Pistorius’s strategy worked in a court of law, where someone’s intent can be hard to prove, in the court of public opinion, the feeling was thsat he had gotten away with murder. Though no one used the term “sociopath,” the comments after the news of the verdict described his behavior as the acts of a sociopath.

To illustrate, here are some representative comments from the most recent social media comments I reviewed—virtually all of the posters did not believe he accidentally shot through the door. Rather they took the view that this was a classic case of murder out of jealousy or revenge, after which Pistorius used his lies and money to escape the charge of murder. Some critics even compared him to OJ Simpson, who also killed his ex-wife and got away with murder.

Tons, for instance, had this to say:

Pistorius is the OJ Simpson of South Africa, He is not an actor but surely he passed screening. This legless man was fortunate enough to marry a beautiful woman and enjoy flirting while married. I believed he killed her because she is leaving him and because she couldn’t put with his bad behavior as explained by his former girlfriend. OJ Simpson was also fortunate to marry a white woman. She divorced him because he is manipulating and controlling too …Both of these killers got away with murder

Terrence considered Pistorius’s behavior in the court room all an act. As he noted:

…This guy is totally guilty. OP blatantly shot this woman, and put on that bull (sh)(it) act in the court room.

For Rich Rodriguez, Pistorius’s actions showed he was immediately in cover up mode after killing his girlfriend. As he observed:

So nowadays an intruder climbs into your bathroom from the outside and locks the door. How is he going to steal anything while being in the crapper.?? In addition, Pistorius had to reach under the bed for the gun and he could not see that Reeva was gone??.. Pistorius knew Reeva was in the bathroom when he went for his gun, and when she wouldn’t open the door he shot her. After the murder the first person he calls was his manager or handler and not 911 or the police. An hour after he shot her and after they had their story concocted, they then called the authorities.

Finally, to cite one more comment from Quietlyoutrageous, Pistorius’s ntent to kill and cover it up with lies was obvious:

OP- GUILTY AS THEY COME! What a crock of rubbish to think he did not have intent to kill! One shot ok, but anything over 3 shots is intent to kill period! He knew exactly who was in the bathroom, No one in the world is that stupid to not know and if he wasn’t some celebrity then he would already be behind bars where he should be!

In sum, though no one used the term “sociopath” in reacting to the Pistorius actions and his trial, the general consensus was that Pistorius acted intentionally and afterwards tried to get out of the responsibility for what he did by claiming a fear of an intruder led to a tragic accident. Those who provided these comments believed he lied to escape the consequences of his actions, just like a sociopath might to get what he wants—in this case, freedom from punishment for his actions. And the strategy worked well, since the verdict was “culpable homicide” instead of murder, and a five-year sentence that could result in as little as ten months in jail, followed by the rest of the sentence served under house arrest. As of this writing, after the prosecutor appealed the verdict of manslaughter, an appeals court of five judges found Pistorius guilty of murder on the grounds that he would have known that shooting through the door would have killed whoever was behind it. The court also found that the original trial did not “take into account all the circumstantial evidence involved in the case, including key police evidence, which was in error.” Thus, Pistorius will now go to court to receive a new sentence, which could be as little as 15 years, which is the minimum punishment for murder in South Africa. Potentially, he could still appeal on the basis that his Constitutional rights have been violated, and he is now under house arrest, while awaiting the next step in the process.

Thus, in very different contexts, lying can be used to achieve goals and evade consequences—whether in a work/school environment or in one’s personal life, as further illustrated in the following chapters.