Three

STORM SURGE

DESTRUCTION,

SOLUTION, SUCCESS

Marina del Rey was opened for business in 1962. Bidders for leaseholds were being solicited. In mid-July the same year, offshore storms subjected the marina to excessive wave action. The US Army Corps of Engineers accepted the responsibility of finding solutions to abate the energies. A scale model of the harbor was established at the Waterways Experiment Station in Vicksburg, Mississippi. The model indicated that the most extreme conditions would affect the Administration Center, while other areas would experience intense to moderate effects. In an actual weather event in mid-December 1962, Westside Marina boat owners were unhappy with the violent action of the docks brought on by severe storm surge waves. However, it was the devastating storm of January 1963 that produced heavy wave tidal damage to the Westside Marina as well as to the Harbor Administration Center and Pieces of Eight restaurant. An immediate solution had to be found. Again, the Pacific Ocean was trying to reclaim its marshlands. (Courtesy of LACFD.)

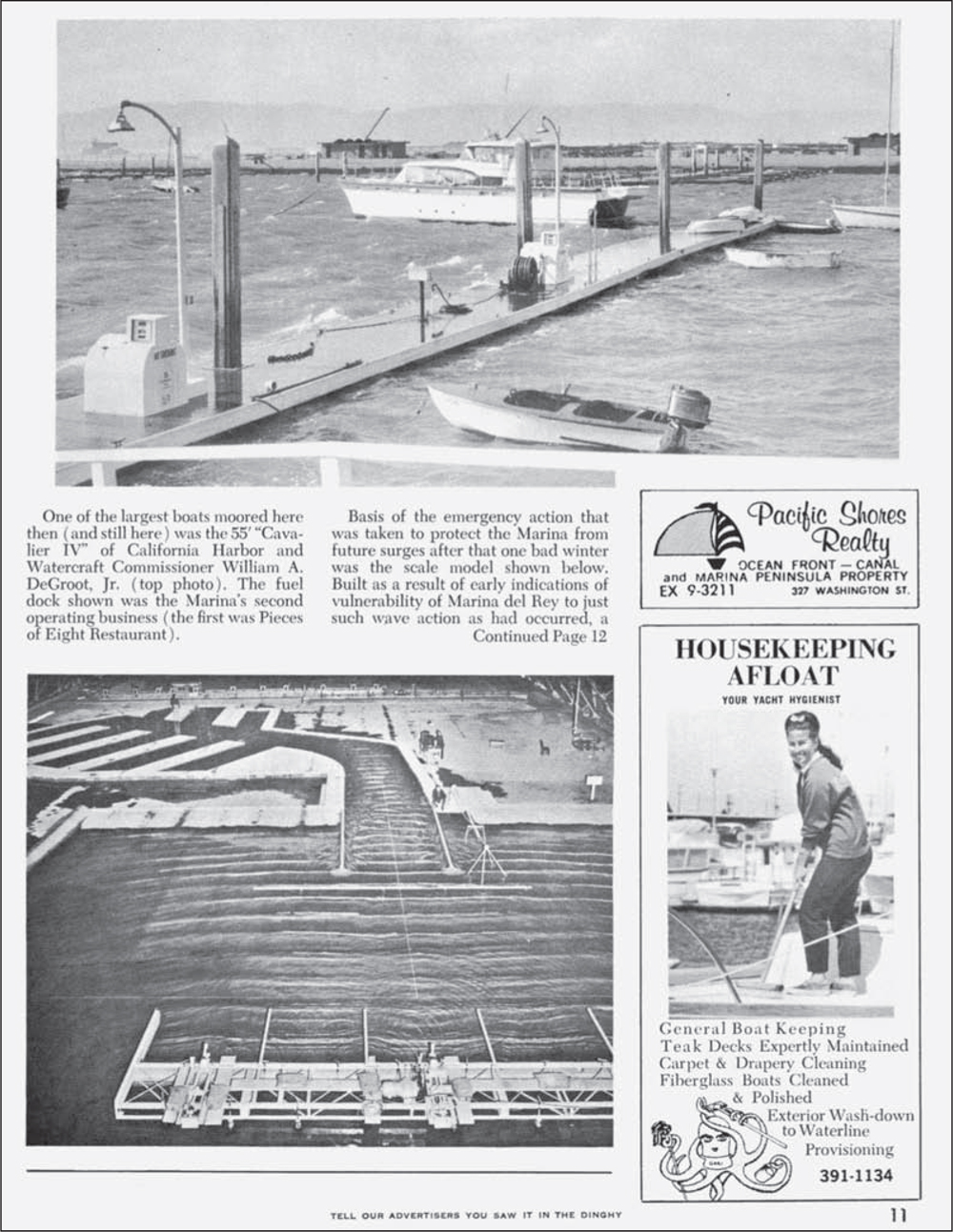

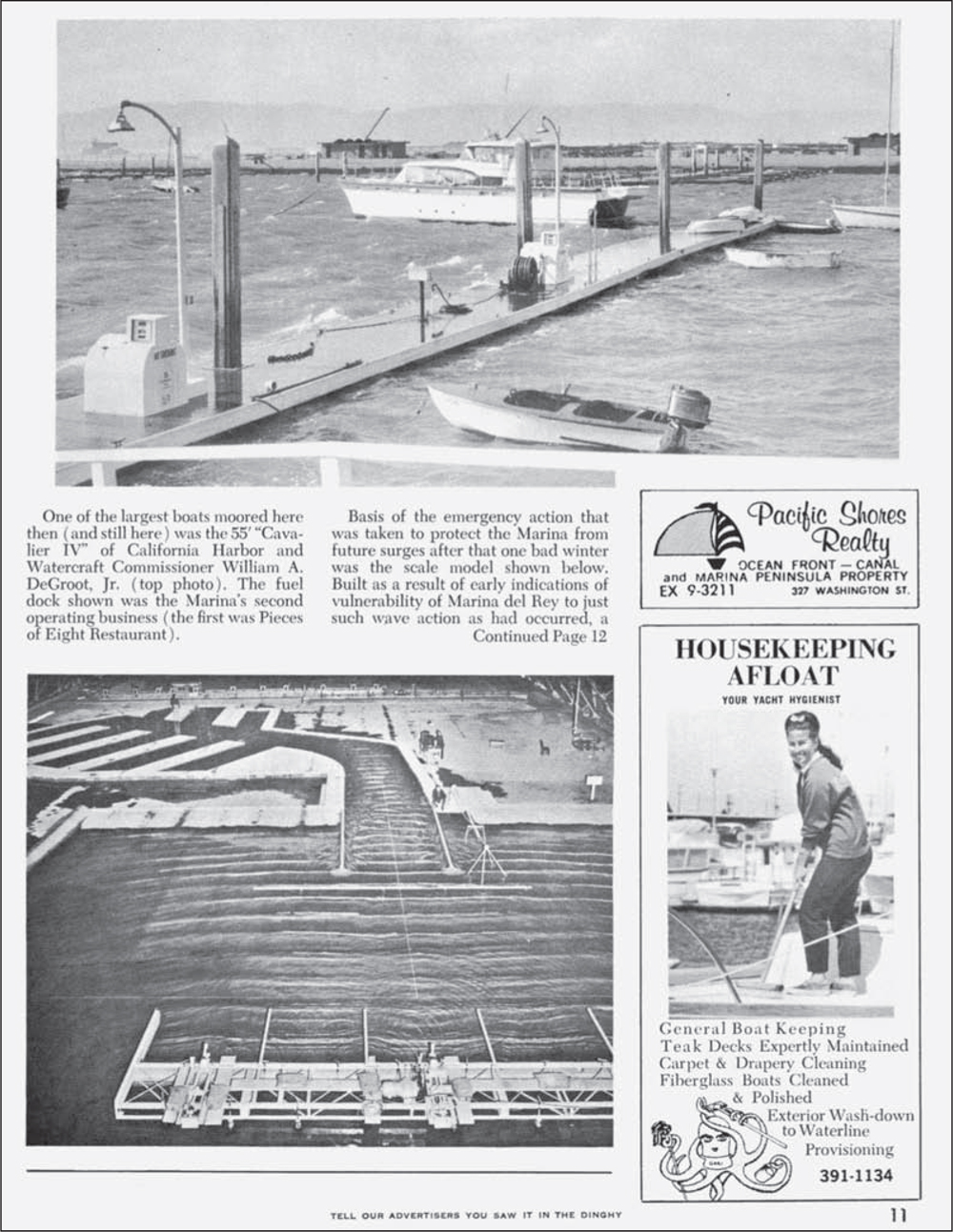

Strong storms in the Pacific Ocean, hundreds of miles offshore, create wave action that funnels strongly into Santa Monica Bay. In January 1963, a violent surge upended docks, pilings, and utilities, as shown here. Boats were removed from the Westside Marina, which was closed on February 11, 1963, until the docks were repaired. (Courtesy of LACDBH.)

Vessels were anchored in the center of the marina to escape damage. The photographs on the next five pages are reproduced from the November 8, 1968, issue of Dinghy magazine, which revisited “the Big Surge.” Publishers Ed and Betty Borgeson later sold the marina’s only boating publication to Darien Murray and Greg Wenger. Dinghy ceased publication upon Murray’s death in 2002. (Courtesy of LACDBH, 1963.)

The November 8, 1968, issue of Dinghy recaps the devastating surge that almost ended the establishment of the new Marina del Rey harbor. The article begins, “Six years ago, in the winter of 1962–63, the fledgling Marina del Rey harbor was beset by what has since become known as ‘the Surge.’ Large and rapid swells built by distant tropical storms far down the coast of Mexico, which once every 50 years or so make a direct hit on our local coastline, drew a bead that winter on the unprotected mouth of the new Marina channel.” (Courtesy of MDRHS.)

The height of the advancing surge along the bulkhead in Basin A at Caballo del Mar (later renamed Tahiti Yacht Landing) is shown in the top photograph. The kind of damage done to the slips here and at the newly completed Westside Marina is shown in the bottom photograph. (Courtesy of MDRHS.)

Damage from the surge included the sucking away of the fill land, shown in the top photograph, at the site of what is now a part of the Marina Point Harbor apartment complex in 1968. The site is seen from the same vantage point in the bottom photograph. Note the advertisement for a full, one-year boat protection service, offered for only $10. (Courtesy of MDRHS.)

One of the largest boats moored was the 55-foot Cavalier IV, belonging to California Harbor and Watercraft commissioner William A. DeGroot Jr. The fuel dock in the foreground of the top photograph was the second business open in the new marina, following Pieces of Eight. The surge model had been well under way by the US Army Corps of Engineers, due to the vulnerability of the marina to such wave action. With the storm, the study was put on a “crash” basis. (Courtesy of MDRHS.)

Very dark predictions were made in the press and elsewhere during early 1963 that the new marina was done for, that it was an amusing but fantastically expensive mistake. However, the solution to the problem was begun by the following winter. The new breakwater was started in October 1963 and completed in 1965. Temporary baffles were removed, and the marina was free from the threat of future surges. (Courtesy of MDRHS.)

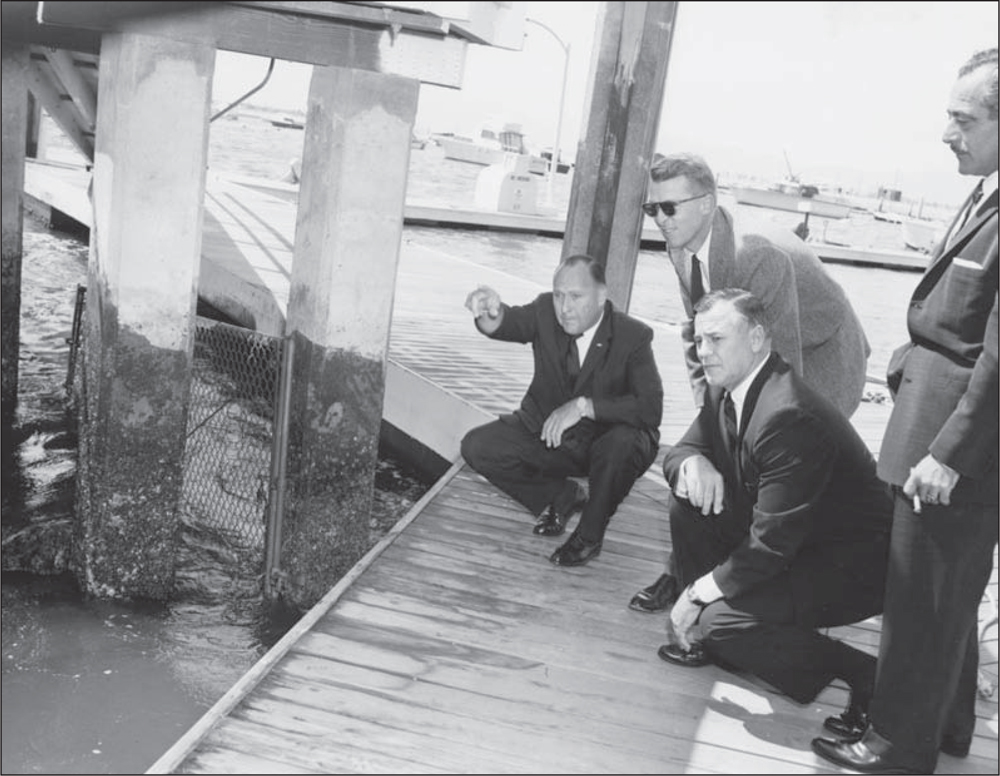

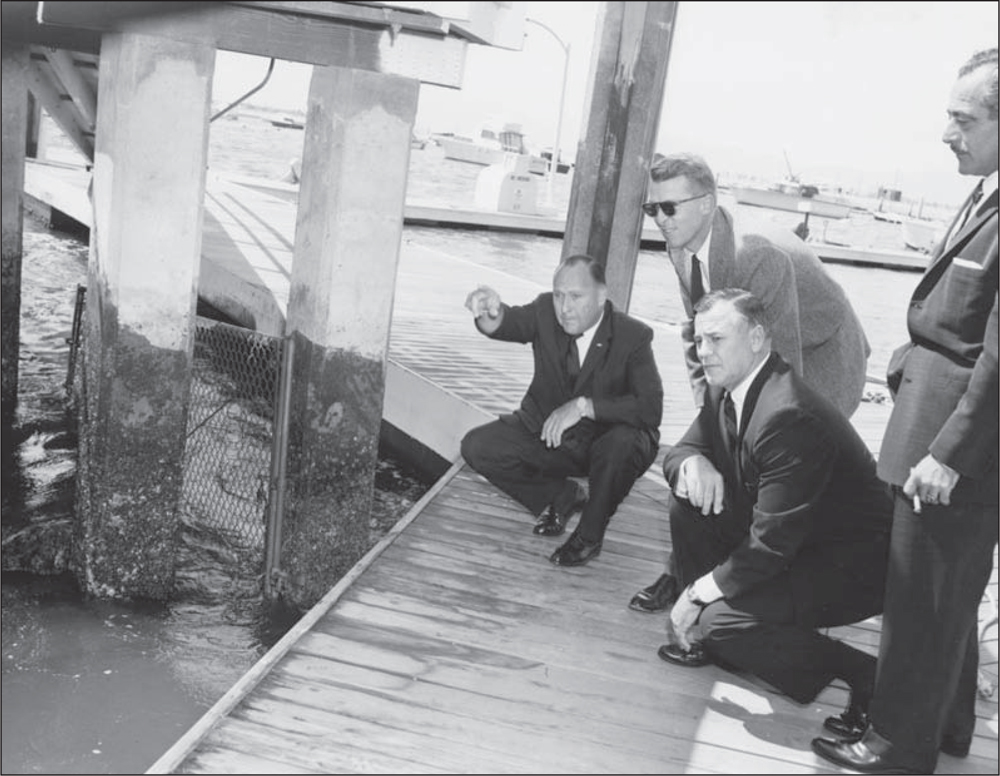

Surveying the damage in 1963 are Aubrey Austin Jr. (left), chairman of the Marina del Rey Small Craft Harbor Commission, and Art Will (second from left), director of Marina del Rey. The two other individuals are unidentified harbor commissioners. It appears that the dock and pilings have separated. (Courtesy of LACDBH.)

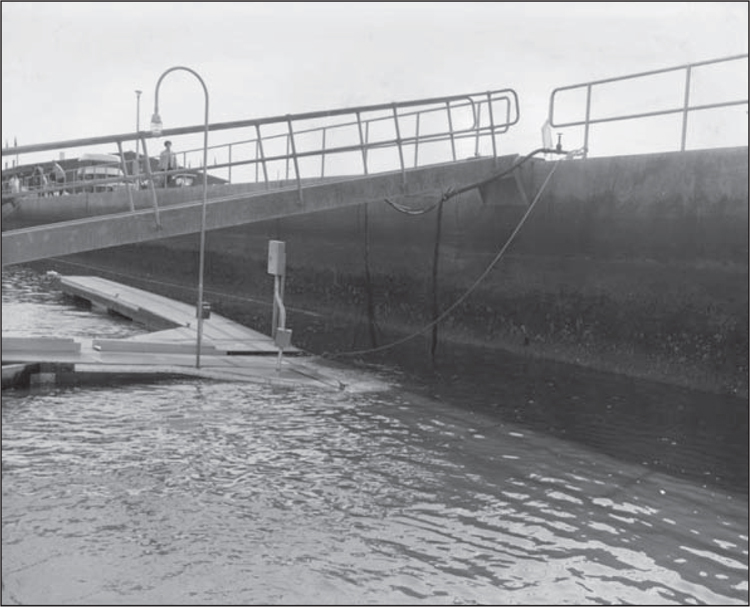

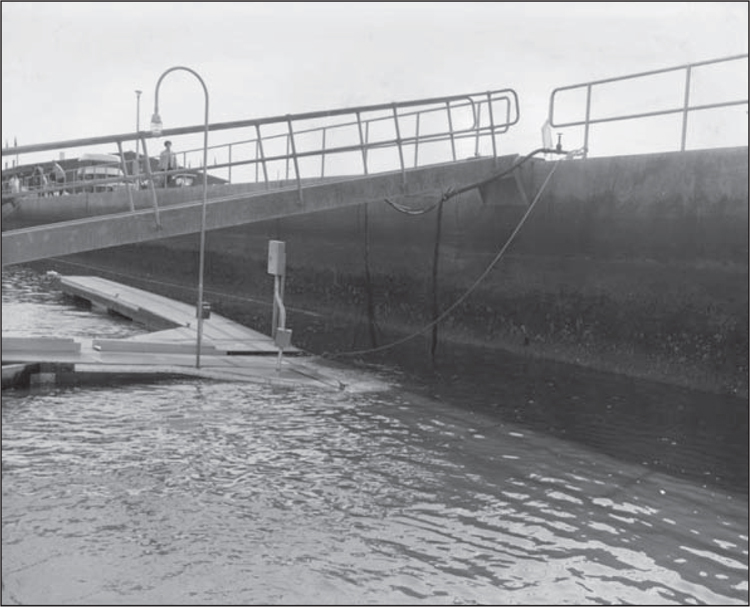

In this 1963 photograph, the gangway leading to the walkway along the finger where the boats are docked appears to be twisted. The dock under the ramp is broken and not connected to the walkway. Excessive wave action has apparently crunched the dock against the seawall and twisted it apart. (Courtesy of LACDBH.)

As seen in the above photograph, taken in 1963, the “washing machine” wave action undermined the walkway along the seawall at Pieces of Eight restaurant (right). The damage was especially intense in the area next door, where the Harbor Administration Center is located on Fiji Way (below). The severity of the surge intensified the urgency for the US Army Corps of Engineers to speed up its short-term solution for immediate prevention of more damage as well as to develop a permanent safe-harbor plan. Fortunately, both county engineers and the Corps of Engineers had already been studying previous wave and tidal actions at the Vicksburg Experimental Station and were prepared to move on a plan to build a temporary baffle system to prevent more damage while a permanent deflection breakwater was being constructed. (Both, courtesy of LACDBH.)

The director of Marina del Rey, Arthur Will, journeyed to Vicksburg, Mississippi, to the Army Corps of Engineers Experimental Station, where wave studies were being conducted with the tank model of Marina del Rey. Standing on a simulated mole with two unidentified Army engineers in 1963, Will (center) watches the machine-generated wave action effect on the seawalls and ponders what might be done to mitigate adverse effects. (Courtesy of US Army Corps of Engineers.)

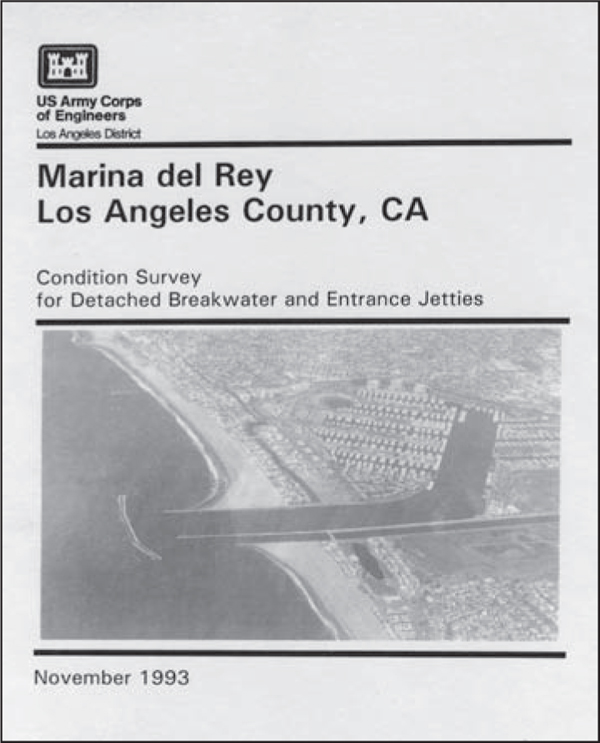

The resulting investigative and hands-on research findings were later published in a 1993 engineer’s manual. The results conclusively show that a range of wave actions could cause extensive damage in certain parts of the marina. The engineers recommend short- and long-term cures: First, install temporary sheet-pile baffles across the entrance channel; second, build a permanent detached breakwater. (Courtesy of US Army Corps of Engineers.)

In the above photograph, the generated turbulent wave-water action damage can be noted on the area corresponding to the location of Pieces of Eight restaurant and the Harbor Administration Center. This action indeed occurred in January 1963. County files indicate that 11-second intervals with close to 15-foot waves had been recorded in previous years, which is why the model had been constructed earlier to study known wave actions. Below, the same wave-tidal action produced little to no damage on the scale model experiment when a breakwater was added to the mouth of the entrance channel. The decision was made to build a breakwater. (Both, courtesy of US Army Corps of Engineers.)

The US Army Corps of Engineers at Vicksburg also modeled the breakwater with great precision as to water-wave and tidal actions under various storm conditions. Seasonal aspects were considered. It was usual for the wave actions to be less pronounced in the summer months, so a time window came into play for the construction of the detached breakwater. (Courtesy of US Army Corps of Engineers.)

The model study without the breakwater shows wave-tidal action definitely entering the channel entrance and proceeding directly into the marina main channel. As the marina harbor is now contained by concrete seawalls, the funnel effect increases the turbulence of the water and can be destructive, as previous inner harbor studies showed. (Courtesy of US Army Corps of Engineers.)

By placing the scale model under various simulated weather patterns, the optimum placement of the breakwater was determined. The wave action is virtually nil in the protected entrance channel area in the model test. The height, width, type of stone, and construction layers are specified in “The Marina del Rey Typical Breakwater Cross Section,” issued by the US Army Corps of Engineers. In the photograph to the right, the framed “souvenir” edition is being accepted in 1963 by chairman Aubrey Austin Jr. (left) and marina director Art Will (center). Officer Peacock of the US Army Corps of Engineers (right) is present at this initiation of the start of construction of the detached breakwater. (Both, courtesy of US Army Corps of Engineers.)

Chairman Aubrey Austin Jr. (left), engineer officer Peacock (center), and marina director Arthur Will hold large rocks and are poised to toss the material at the spot where the new breakwater will be built. The ceremony took place on September 20, 1963, with barge No. 8 standing by. (Courtesy of US Army Corps of Engineers.)

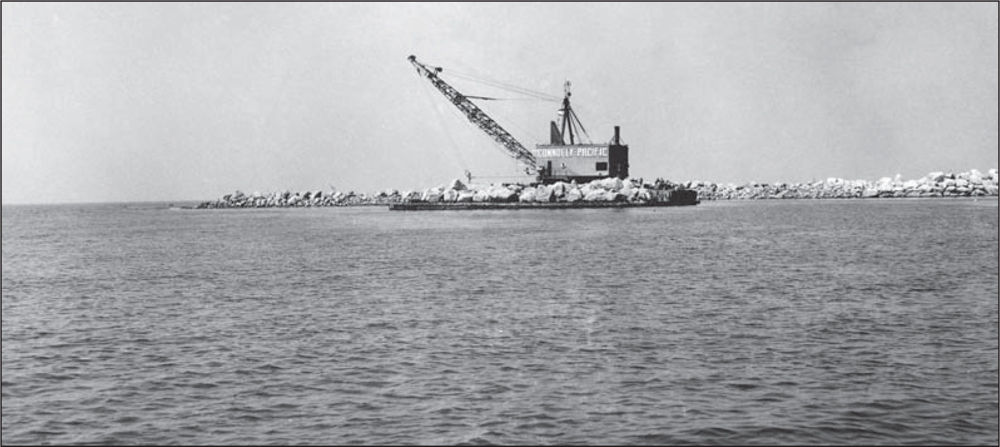

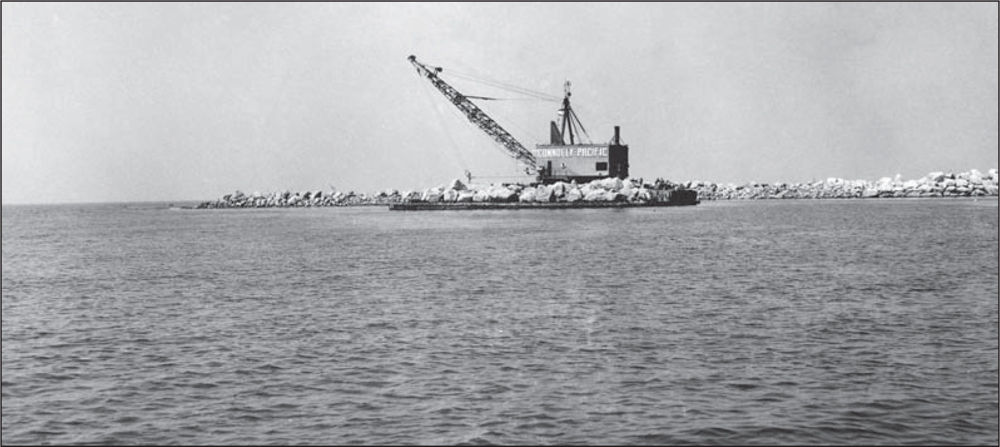

Connolly-Pacific Company started work on October 15, 1963, after being awarded a special federal appropriation. Many Marina del Rey original leaseholders and county officials lobbied intensely to Congress and the Senate for funds. So, once again, the giant crane lifted boulders off the barge brought from the Catalina quarry, onto the new detached breakwater, as seen here in 1964. (Courtesy of LACFD.)

For temporary protection to the inner harbor, sheet-pile baffles were installed a few feet south of the US Coast Guard station and extended 450 feet into the main channel. On the west side of the main channel, but staggered about 200 to the west, another set of baffles 450 long was installed. Marina waters were placid while the detached breakwater was being built. There was plenty of room for boats to enter and leave the harbor, as seen here in 1963. (Courtesy of LACFD.)

In this 1963 photograph, the baffle from the east side of the main channel can be seen jutting out of the riprap just below the residential Villa Venetia apartment buildings, under construction at the end of Fiji Way. The undeveloped areas beyond Villa Venetia are Ballona Wetlands, now a protected habitat. On the right is Ballona Creek. (Courtesy of LACFD.)

The detached breakwater is halfway finished in this 1964 photograph. Waves can be seen crashing against and over the rocks, while the crane sits in the relatively protected non–wave action leeward section. The prevailing wind is usually from the west, so the high rock formation also protects against heavy wind as boats enter Marina del Rey. (Courtesy of LACFD.)

While the breakwater is being built, 82-foot Coast Guard cutters wait in readiness for water rescues or emergencies in 1964. Los Angeles International Airport is six miles to the south of Marina del Rey, with air traffic landing and taking off over the ocean. Leasehold development of the commercial and residential structures intensified after the viability of the marina had been secured. (Courtesy of LACFD.)

Success! The detached breakwater was completed in January 1965, with final wrap-up and formal dedication of Marina del Rey taking place on April 10, 1965. This event signaled that the facility had finally achieved its goal to be the largest man-made marina in the world. Designed for a capacity of nearly 6,000 pleasure craft berthed in water slips, the number expands to 8,000 when dry-storage boats are included. The number swells when trailer boats are launched from the public ramp. Potential leaseholders began bidding for restaurant parcels. Apartment parcels were snapped up by developers, who achieved nearly 100 percent occupancy. Seasonal day populations often exceeded 30,000. Yet to be built are several parks and public facilities. (Courtesy of LACFD.)

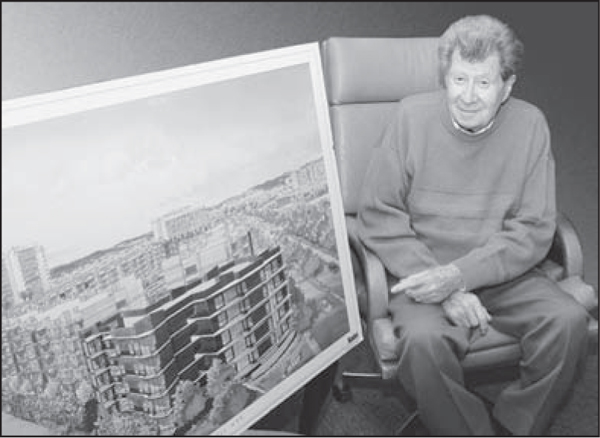

Above, Sen. Thomas H. Kuchel (left), of the California Senate Appropriations Committee, is recognized in 1964 by Los Angeles County officials for his assistance in obtaining federal funds for improvement of Marina del Rey’s yacht harbor. The work helped to prevent a recurrence of wave damage experienced in 1963. Senator Kuchel was presented with a symbolic piece of rock from the first barge load deposited in the new offshore breakwater. He was also given a resolution of county appreciation, with photographs of a model of the new protective project. Shown here with Kuchel are, from left to right, Joseph M. Pollard, administrative assistant to county supervisor Warren M. Dorn; county engineer John A. Lambie; and director Arthur G. Will of the County Small Craft Harbors Department. Also instrumental in obtaining funds were Aubrey Austin Jr., chairman of the Small Craft Harbor Commission, and Jerry Epstein (below), a major Los Angeles real-estate developer of Parcels 23 and 24. (Above, courtesy of LACDBH; below, courtesy of Greg Wenger Photography.)

Construction of Mystic Cove Marina by leaseholder David Jennings is visible in the lower foreground of this 1965 photograph. The anchorage-only parcel suffered little damage in the storm surge because of its location deep into Basin F. The Marina del Rey Hotel (center) now has boat slips constructed on the south side of the mole. (Courtesy of LACDBH.)

Located at the main entrances of Marina del Rey are large information standards showing the configuration of the marina and directions to the few businesses and marina anchorages already built in 1966. In order to become the world’s largest man-made marina, the County of Los Angeles had to bring in developers and users. (Courtesy of LACFD.)

Marina “country fairs,” including amusement-park concessions, food booths, merry-go-rounds, and Ferris wheels, were set up to provide a fun experience for visitors to the new marina site. Evenings and weekends were usually filled with some kind of entertainment that could take place on the empty land. (Courtesy of LACDBH.)

Another event intended to attract the public’s attention to the location of the marina was a mini-zoo exhibit. It occupied the empty parcel between Admiralty Way and Lincoln Boulevard and between Bali Way and Mindanao Way. The windmill building in the background is the iconic symbol of the Van de Kamp’s Bakeries, which stood on the east side of Lincoln Boulevard. (Courtesy of LACDBH.)