7

THE DIAMOND TRACK TO TRIPOLI

Reflections on Leaving for the Blue

Yes, there it is – ‘Dauntless B.F.’ down on the draft, together with two or three other stalwarts – to return to the Blue on Thursday, just two days away.

So he wanders away from the notice board, just a little disturbed and agitated but not before he has ascertained, to his secret pleasure, that a couple of his particular cobbers are to make the trip with him ... Then he returns to his hut and sits on his paliase and contemplates his kitbag with gloomy interest. The end of Base Hospital with these smooth, cool, unreal sheets, a bed off the ground, a bed with springs and a mattress in place of the inevitable sand and the equally inevitable stone located just under the hip. Meals brought right to one – meals that were different with fresh bread, fresh vegetables; things not out of tins. People doing things for one for a change, but it’ll be good going up with Sonny and Bob and we’re travelling by jeep. At least we won’t be rattled and jolted in a three tonner.

Yes, back to the Blue again; those sandstorms sweeping hot choking sand over and into everything. Boring along tracks feet deep in dust finer than flour, till everything is white, and everyone is irritable. Stuck in the soft sand ... stuck in the mud after rain ... flies, hell-possessed little demons ... the chilling feel as shell splinters go whee-ing a thousandth of an inch above your tenderest spot ... ‘They’re Stukas ... no they’re ours ... they’re George’s ... by God, take cover!’ That tickling right in the centre of your back as you lie in that mere furrow of a slit trench and wait those agonising seconds of a bomb scream. Biscuits and bully and margarine ... spoon meals always and ever ... meals eaten always with the ubiquitous spoon. That’s what it’s like up in the Blue ... but it will be good to be up there again with the boys.

And so Gunner B.F. Dauntless sorrowfully empties out his kitbag. Away with shoes, that silk shirt, those pyjamas, that pair of slacks. Into a sandbag with the contents of those parcels from home: those cakes, oysters, tongues, gingernuts – they’ll be good up in the Blue.

After the Breakthrough

From the breakthrough on the 4th November to as far as Tripoli the Division was never seriously engaged with the enemy. It joined in the chase, it executed outflanking movements, and from time to time it contacted enemy rearguards, but never did it fight a major battle. The story from now in becomes an account of long desert treks; of weeks making new tracks in desert wastelands. It is a saga of quick encirclements, night marches, treks over broken country, engagements with small rearguard forces and of the endless panorama of burnt-out and abandoned tanks and vehicles.

I think the chief feeling among the men [about the breakthrough] was relief, mixed probably with the exhilaration of a victorious advance; relief that at last they were divorced from static warfare. Chappie expressed it to me nicely: ‘We felt as if we were freed from a cage.’

Several times the column was forced to halt to take prisoners. These came in groups from all over the desert, most of them Italians, with an occasional German, all of them thirsty and tired. For instance, a column of enemy vehicles was sighted on our southern flank. The Commanding Officer went forward and engaged them. They in turn deployed and fired back. Two Sherman tanks were sent forward to assist. It was all over in a few minutes. Thirty prisoners and two vehicles were brought in. Later three truck-loads of Italians wandered in from the blue and gave themselves up. Then came a German motor-cycle and side-car, the crew of which surrendered to our T.S.M. Out of the side-car stepped a German officer.

‘I am a German officer,’ he stated in a peculiar accent, ‘and I demand to speak mit an English officer.’

‘Well I’m a bloody Kiwi sergeant-major,’ replied Fred, ‘and you’re coming with me, George.’

When the Battery Commander came over, the Nazi saluted smartly and once more said, ‘I demand to know what will happen to us at dis moment.’

‘At this moment,’ replied Major Bevan, ‘you’ll go with the sergeant-major.’

He went.

The Captured

Wire-whisker

Somehow, the New Zealander abroad combines the truculent aggressiveness of his cousin the Aussie, with a sympathetic tolerance of every man’s way of living. He will eat repulsively oily salad at the hospitable board of a Syrian Muqta, or drink floor polish with a Greek peasant, with the same unself-conscious ease of manner with which he tackles caviar at the country seat of a dowager duchess.

These graces combined with his firm refusal to be bullied have granted him countless exemptions from the regimentalism of a British army. Thus, the case of one ‘Wire-whisker’, a hard-bitten ex-seaman who joined the 6th Field Company as a sapper. After the famous breakthrough at El Alamein the Company was engaged in clearing tons of rock from the steep cuttings where the main desert road wound up the escarpment near Sollum.

Wire-whisker was laboriously placing charges of gelignite, tamping and laying fuses in the burning afternoon sun. Someone came and leaned on his shoulder peering into his work, obstructing his movements. He burst into a torrent of abuse without even turning round. ‘What the b-----hell do you think you’re doing here? This is a blank dangerous area. A man’s trying to do a b----- tricky job and every fool with nothing to do comes poking around and getting in his way. Now get to hell out of it and let me–’ his words died away as he looked, around pop-eyed. But the recipient was a fair-minded man, as well as a strict disciplinarian.

Without a word the man, who is now Field Marshal Sir Bernard Montgomery, walked off down the road.

Derna

‘She’s a whopper when she rolls,’ said a dusty New Zealand driver as he sat during a boil-up and stirred the sand of his desert stove with a bayonet. ‘She’ is the New Zealand Division, and when she rolls she is undoubtedly a ‘whopper’ ... It stretches from one horizon to another. Yet every unit, and vehicle, has its appointed place in this great procession.

The ‘Left Hook’

After five days travel covering nearly 400 miles, we halted again and dug in near two fighter dromes at El Haseiat. We stayed only two days, just time to service the jeep thoroughly then moved south again in a huge outflanking attempt to threaten the rear of the German defences at El Agheila, while allied forces thundered on his front door. The days went by in continuous travel, south and further south, in what was to become famous as the ‘Left Hook’ operation. We passed some bearded patrols of the Long Range Desert Group, and saw a few gazelle and Bedouin. Then we went west at night round the Crystal Hills, following the red lights set along the route marked by the black diamond. It was tiring driving. The whole move was marvellously planned and signposted, and the preparations must have been terrific. Petrol dumps had been prepared, tracks surveyed and bulldozed. The five-day journey went without a hitch or hesitation and, about the middle of December, after an all-night drive, we were on the road behind the Hun line and closing in. Rex joined us in the headquarters group, driving the colonel’s carrier.

As the day progressed, excitement grew intense. We went forward with the brigadier on a reconnaissance ... we all joined up with General ‘Tiny’ Freyberg in another car, with his Honey tank alongside. Two more staff cars and a couple of jeeps swelled the party. Freyberg was highly elated. We all stopped on a ridge, but not seeing what he wanted to see, Tiny leaped back into his car and waved us forward to the next ridge. It was a roaring circus of vehicles ... everyone was intent on keeping as close as possible to the general and we drove each other down with a brutal callousness, brigadiers cursing drivers and drivers cursing brigadiers as we jockeyed for position.

On the next ridge the colonel [Webb] went forward with Freyberg and the brigadier [Gentry] and we could see Tiny demonstrating his orders with great gestures as he pointed ahead to the road ... We could feel that there was some urgency in their planning. Suddenly Kenny and I were beckoned forward. It was our moment. The jeep leaped ahead, scattering a group of brigade majors and staff captains in a bow wave of flying sand. We received orders to return to our battalion [24], which was still on the move, to give the intelligence officer a new bearing on a converging axis of advance, and gather the company commanders together and bring them to the colonel, two miles forward of our present position.

Kenny took the jeep through the bunched cars in a screaming arc, yelling at the top of his voice in excitement, then we headed across the desert to cut the battalion off. After about ten miles we contacted their flank as they rolled steadily on. We drove to the head of the column and gave the intelligence officer in the leading vehicle his orders. Then we circled the battalion gathering together the company commanders, and shot off once more on a tangent at top speed with three half-ton pick-ups in line behind us. We passed the divisional group still on its ridge, busy with map cases and field glasses. They gave us valuable directions, just as we were beginning to wonder whether we had got completely lost with the three company commanders. I was sweating at the very thought. We found our Colonel with the brigadier at the appointed spot. The orders group held a brief reconnaissance then we drove slowly forward to converge with and rejoin the battalion. Dusk was beginning to fall, after a day of intense movement in exalted circles for Kenny and myself. I would always remember it as one of the most exciting days I ever spent.

The battalion pushed forward into the evening, over increasingly rough country. The troops had had a tiring journey. We had been on the move for nearly twenty hours, with very brief stops for brew ups. As darkness increased the going became even worse, and without lights, the trucks gradually bunched up to maintain visual contact. Tired drivers, working like mad, swung their three-tonners up and down across the wadis, slammed down the sharp declivities and ground up narrow defiles and brief escarpments. The infantry in their bucking, swaying vehicles, must have had a wretched time as they prepared to attack immediately after de-bussing.

Never did I admire the infantry more than on this occasion. When the ridge was reached at 2300 hours, the trucks lined up side by side and a start line was improvised in front of their bonnets. The companies filed out, took up their position, and in half an hour had started the attack. There was no artillery support, as the guns had been left miles behind during the day’s travel. The battalion’s three-inch mortars and anti-tank guns were the only supporting weapons. All vehicles retired as the attack went in. We were left beside the RAP and an American ambulance, to follow up with the anti-tank when the flare signal was given. The infantry had progressed about four hundred yards when they met heavy fire from mortars and Spandau machine guns. They must have pushed another 50-100 yards through this beaten zone before we heard the first Bren open up.

The fighting became general right along the ridge as they worked their way forward, further and further away from us. The American ambulance driver was an interested observer as we lay beside our vehicles peering forward under the rims of our steel helmets at the progress of the battle. He echoed our sentiments when he said with conviction, ‘Them guys are all right.’

The success flare went up and we drove forward ... The companies were all in position but unable to dominate the road as well as had been hoped, and the anti-tank boys went out to them in support. In spite of efforts made by the infantry and the carriers, we heard German transport rolling past all night just off the road, by-passing our position. The Hun started shelling our position before switching to the wadi behind us, where daylight revealed the brigade’s B Echelon transport in a confused tangle.

Later that day our artillery came up and the Hun retired under their fire ... A graphic story could be read in the abandoned enemy positions. Tanks and mobile gun positions had been dug in to face an eastern front, then suddenly they had realised an army division was approaching from behind. You could see the slur of tracks as vehicles were turned to face the flank and the haste in which positions were dug in to face a new front ... The Hun broke out of his line at El Agheila and retreated along the coast. We remained stationary for three days, as most of the petrol was taken to replenish armour, leaving only sufficient for 50 miles per truck.

During this immobile period we got our first chance for a long time of a really thorough wash and change of clothes. It was a great treat: I had almost reached the stage of keeping windward of myself.

On 20 December the battalion moved through Nofilia to a spot near the coast where we bivvied over Christmas and New Year. Christmas dinner was a traditional army affair with officers serving the men ... The food was good, the cutlery non-existent, but a great deal of effort had been put into the rations and their preparation. We squatted cross-legged on the desert, our mess tins on our knees and enjoyed the moment. It was no great hardship for the officers – they stood briefly on the wrong side of the dixies, ladle in hand. Normally they ate just as we did, officers’ mess being a thing unknown while on campaign. I went to a Christmas service in the afternoon and spent the evening writing home and to Nan, all such a long way away.

We had a bottle of beer each in the evening. Beer was very scarce. General Montgomery had discovered that a bottle of beer took up approximately the same space in a ship’s hold as a 25-pounder shell, and preferred the more lethal cargo.

Grave Near Sirte

‘How are things going?’ asked the General.

‘Fair sir,’ said the sentry, looking glum.

‘Don’t worry, we’ll be in Tripoli by the 25th, said the General.

The sentry reflected on this. ‘No sir, that won’t do.’

‘Why?’ the General asked.

‘Because it’s my birthday on the 23rd, sir.’

‘Well we’ll see what we can do,’ The General promised with a smile.

The sentry saw the Union Jack flying over Tripoli on the 23rd.

First New Zealand Troops Move in

Jan 23 – Tripoli at last! Little more than an hour ago – it is now three in the afternoon – our most forward troops, a Maori Battalion company, reached the outskirts of the city, followed closely by other New Zealand forces. They will be the first Dominion troops of occupation in Tripoli and will camp among trees and green surroundings, most welcome to the eye after weeks of the weary desert journey from Alamein.

All the way across the hundreds of miles of desert the Eighth Army has crossed since the Alamein line broke in early November, The New Zealanders have taken the hard inland route. By careful route-planning and superb driving many difficulties were overcome in our earlier sweeps, but in this last 400-mile drive from the Gulf of Sirte to Tripoli, our tanks, guns and hundreds of three-ton trucks, have crossed a variety of the wildest possible country and at a speed which brought them to Tripoli only a few hours behind the forces driving along the easier coastal route.

In a small village about ten miles from the city, General Freyberg stood on the roadside. He was saluted by his men as they passed, though, some did not salute – they waved, and their waves were returned – there was nothing ceremonial about it. The men welcomed the sight of the leader who had brought them to the goal they had had in mind for so long. There was many a handshake at the Azizia Gates, still a few miles from the heart of the city, with Maori Bren carriers strung along the roadway ... There was a sound of distant explosions, which brought the comment from one Maori soldier ‘I hope they haven’t blown up the brewery.’

Tripoli

On Thursday, February 4th, we had a big day when Alan, Dick and I cleaned the truck out thoroughly and then removed the detachable canvas hood. All the spit and polish was in preparation for a ceremonial parade and an inspection by Winston Churchill who had flown to Tripoli. When all was ready our regiment moved out in column of route and proceeded to the other side of Suani where an area had been cleared for the occasion. We had a practice parade and march past and returned to an assembly area for lunch. At two in the afternoon the British Prime Minister arrived and then, in company with General Montgomery, made an inspection of the New Zealand Division by car. Alongside the General, with his brown sun-tanned features, Mr Churchill looked a real ‘pale-face’ but of course he had just come from the middle of an English winter.

Being tall I was on the right flank of our battery line, consequently seeing the great man at fairly close quarters and distinctly hearing him say to General Montgomery; ‘These are soldiers.’ That was praise enough for any troops. After a short speech by Mr Churchill we marched past on foot and shortly afterwards rumbled past him with our vehicles in line, and behind us came the 5th Regiment, then the 6th and so on until all units had past the saluting base. We then returned to our camp at Suani and there was a noticeable lack of grumbling usually attached to a ceremonial parade. Maybe Winston Churchill didn’t have anything to do with it, but a couple of days later I was promoted to a full bombardier!!

Churchill inspecting us in the desert after a particularly trying time, many losses, and no reinforcements for a long while. Winnie wanted to know everything.

‘Why do they call the New Zealand Division “Kiwis”?’ he asked quizzically.

Hardened old warhorse that Churchill was, I think my mate rocked him when he answered:

‘Because we are bloody near extinct, sir.’

Some of our men report that a wonderful, incredible heaven lies over a hill a few miles away. The soldier’s dream has at last materialised; for it is said that big Chianti wine vats, thirty feet by ten feet wide and about four feet deep, cover the floor of some of the houses. Here one lowers a bucket on a rope to draw the red wine; then one carries it away in great bottles holding several gallons. It is free. One man fell in up to his thigh, while another who made to rescue him fell right in.

‘War Wastage’

Furneaux Martyn

A week later the majority of us went in to a camp a mile or two out of Tripoli and there Alan and I dug a good deep hole (air raids were inclined to be rather frequent over the town) and put our little bivouac tent over it, firmly anchoring one of the guy ropes to a near-by palm tree. About a chain from the door of our ‘bivvy’ was a garden containing beans and carrots ... we helped ourselves. The young tender carrots were delicious and I ate them by the dozen.

We were stationed there so as to be handy for the job of unloading stores and equipment from the merchant ships in Tripoli harbour. There were no wharves available for unloading the stuff, so it all had to be manhandled and brought ashore in lighters. That job lasted a fortnight and despite the fact that we worked under adverse conditions many times, such as wind and rain in the middle of the night and occasional air raids, the ships were still unloaded. The work we liked most was unloading foodstuffs which were largely American, when being only human, and Kiwis at that, we did very well for ourselves regarding food and drink. There was an excellent brand of grape-juice which seemed to be a particular favourite, and of course tinned fruit was always welcome.

Nelson Bray

It was very important to unload as quickly as possible and to get that ship out of the harbour. Everyone worked really hard, all of the time ... Sometimes to get a truck filled in time I would give them a hand; especially if it was a NAAFI ship. They were always grateful for a hand to finish the job, because some of the boys had worked hard, long hours, and they knew what a dangerous place it was to be. If I saw a box come along of, say, tinned milk, chocolate, tinned fruit or cigarettes, I would forget to put it on the truck and it would find its way into my ambulance. When I got two or three boxes onboard, I was off with my ‘patient’, back to our lines – it all went into our canteen. Then I would go back as quickly as I could in case I had a real patient, and maybe get another box or two.

Roger Smith

Our officers worked like slaves and totally supported suggestions from the more experienced men for getting the job done more quickly. The officers tolerated no transport slip-ups, made sure our tea and food arrived on the dot, and saw that there was a hot shower at the end of the shift. After we had been going for about ten days, we started to get stale and the work slowed down considerably. It was then that Captain Suter, one of the company commanders, hit on the bright idea of working to a set job instead of to a period of time. ‘Get that lighter unloaded and you can go home to bed regardless of the time’ it worked wonders. We unloaded more cargo than ever before and invariably cut an hour off the end of our shift. It involved Suter in endless arguments with the port authorities, as we marched out an hour or more before the end of the period. But no one could deny that the work was being done.

Furneaux Martyn

The more uninteresting and tiring work was handling motor fuels and ammunition, as we couldn’t very well drink petrol or oil, and a 500lb bomb didn’t seem at all appetizing. Sometimes we were working in the holds of vessels out in the harbour and sometimes unloading from the barges on to the dockside. Without the Red-caps, common to the docks where they snooped round to make sure we were ‘good little boys’, the job on board ship was much more congenial. However, despite a certain amount of ‘war wastage’ we, the N.Z. Division, stepped up the unloading rate to something like 2000 tons a day.

Roger Smith

One night we had a surprise raid. A plane sneaked in with its motors cut and caught the whole dock area completely by surprise – the arc lights were full on. We were all grouped beside the old fort on the dock having a cup of tea, and the first thing we heard was the whistle of bombs directly above us and then the sound of motors barking into life. The plane sowed a stick of bombs completely across us, two actually crashing through the dock at our feet. None of them exploded – I can only assume that they were dropped from too low an altitude to ‘arm’. Then the raid started in earnest. I was running for the stone arch over the old portal, my cup of tea held out in front of me as in an egg and spoon race, when I heard yells from the water and returned with a couple of others to see what the trouble was. Apparently a bunch of the boys had been standing on the edge of the dock and on the first whistle of falling bombs they had obeyed the infantry man’s impulse of self-preservation and instinctively flung themselves face downwards – to fall headlong into the harbour. We had quite a job getting them out, as most of them were quite helpless with laughter at their predicament

We spent 17 days and nights on the wharf. On the last night I got Kenny to bring the jeep at about midnight and we stocked it up with a couple of cases of fruit and one of condensed milk and a bottle of rum which Jeff and Bull had stolen – the robbers! Kenny did favours for most of the company, and took quite a load out. By the time we had tied everything on, the jeep looked so much like a three tonner that we just joined a convoy and drove out past the provost quite happily. We all marched home stiff-legged that night, with our battle dress pants bulging. By this time the guards were used to our peculiar gait, and conveniently turned a blind eye.

In a pub in England in 1945 I met a Tommy ... On being told that I was a New Zealander, he turned to me and said, ‘Oo-aye, smasheen jokers these Kiwis ... but wot fookeen thieeeves!’

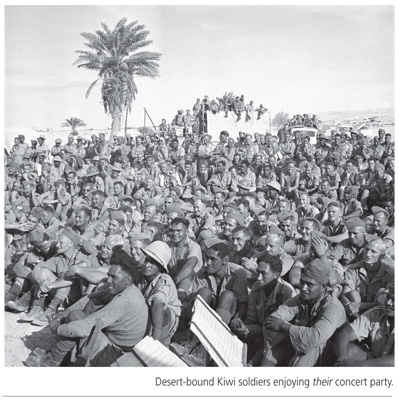

The Kiwi Concert Party

Towards the end of 1943 the people of New Zealand had the opportunity of hearing the Kiwi Concert Party while it was back on furlough from the Middle East ... this quotation from the tour programme:

‘We invite you, ladies and gentlemen, to join, in imagination, the boys of the 2nd N.Z.E.F. at a Kiwi performance in the Western Desert ... the theatre walls and the comfortable seats have gone; the chilly stars are gleaming above you – sit down on the sand, pull up your greatcoat collar against the breeze, for the stage is bounded only by night. From widely scattered dugouts and trucks, you and your pals have walked across the sand converging on the small focus of human gaiety, and oasis of light and sand in a vast black world.

‘The orchestra is seated on their chairs in the sand; the lights flicker up on the front curtain, the man next to you has opened up a bottle of Stella: there’s music in the air; it’s the Kiwi Revue.’

That is literally true, and it happened scores of times from Syria to Tripoli, in foul weather or fine, always to a crowd of men hungry for music and humour.

...on Wednesday, 17th February, we moved out of the Union Theatre [Tripoli] and set up stage at the Miramare, where the great operas of Verdi, Rossini and others had been performed by the world’s leading artists. Here we had everything we required ... all the conveniences of a modern opera house, although it required two days’ hard work cleaning it up and arranging curtains and lights to suit Terry’s requirements for the show.

Under such ideal conditions, the performances had to be good. Even though the speakers gave trouble, and the city light supply gave out at alarming intervals, we managed to get the show over to the huge crowds that filled the seats, overflowed onto the aisles, and crowded on to the sides of the stage. They loved Dick Marcroft’s pitiful item. Dressed most untidily in a dirty battledress several sizes too big for him, great heavy army boots and a side hat that fell over one eye with a classic grace that would have made any modern milliner green with envy, he came on very fearfully to ask Terry, who was conducting the band on stage:

‘Please can I ave a mugev-water?’

Terry referred him to Jim Millins in the wings and off trotted Dick, glancing behind him all the time as though afraid that the band or Terry would throw him out. After a couple of items he would be back, poking his head round the curtain and beckoning Terry for yet another ‘mugevwater.’ This went on several times until Terry got distracted and demanded:

‘Another “mugevwater,” what are you doing with it all?’

‘Well, you see, my truck’s on fire!’ answered Dick in his most lugubrious tones.

‘But surely it must be out by now, with all the water you’ve had.’

‘Oh, no,’ said Dick, ‘my mate’s keeping it going while I get the water.’

It was in this show that Terry introduced the stage band playing ‘The William Tell’ Overture, conducted by that eminent maestro Professor Leopold Popowski – the item that had New Zealand audiences in tears. There can be no doubt about Terry’s artistry, but if there was any, his performance as the ‘eminent maestro’ soon dispelled it; his gestures and antics were clever to the last degree, and the whole satire was polished and finished to its very last note and movement.

The British Public Relations Service had organised a daily newspaper in Tripoli soon after the troops moved in, and they gave us a very glowing write-up:

‘I take my hat off to Terry Vaughan for his orchestrations, his satire of Leopold Popowski, and I take off my jacket to the pathetic figure, scruffy, sorrowful, mug in hand, who interrupts the show time and again to ask for a mug of water.

‘And my shirt – that comes off for Wally Prictor, the prima donna of all female impersonators. Impersonation becomes so finished when Wally Prictor sings, ‘torch-like’ into the mike that you need a course in Pelmanism to remember that the lovely blonde is none other than Sergeant Wally Prictor.

‘And before I finish I take off what is left of my clothing, W.D., in praise of the beefy singer, Tony Rex, and the Chaplinesque humour of John Reidy, the trombone player who doesn’t need to say anything to be funny.

‘So, left in my shoes, I stand in naked praise of the best show in Africa.’