Chapter 2

Abbreviations

The Middle Ages (or medieval period) is present in our daily lives in many ways.1 The same is also true of medieval abbreviations. For instance, the @ symbol (at sign) in our email addresses can be traced back to a letter written by Francesco Lapi, an Italian merchant, dated May 4, 1536, and sent from Seville to Rome.2 In this letter, the @ denotes ‘anfora’ (amphora), then a common unit of measurement.3 Later, the @ symbol acquired the general commercial meanings ‘at the price of’ or per-unit cost.

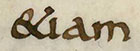

The & symbol (and sign, or ampersand) as it is written today—originally a ligature of ‘et’, which is still discernible in the italic ampersand &—can frequently be found in medieval Latin manuscripts from the eighth century onward in abbreviations such as ‘hab&’, ‘ten&’, ‘ſcilic&’, ‘app&it’, ‘uari&aſ’, ‘l&itia’, ‘&iam’ (Fig. 2.1), ‘&ſi’, and ‘&c&era’, or used separately as ‘&’ denoting ‘et’.4

Fig. 2.1 Lyons, Bibliothèque municipale, MS 324, fol. 3r (Date: 825–50).5

The ∅ symbol (zero sign)—today used to signify the empty set, which has zero members—can be found in manuscripts of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. In those cases, the ∅ symbol denotes ‘instans’ (instant), a moment in time, the duration of which is zero.6 It can also be found in combinations such as ∅ns (instans), ∅tis (instantis), ∅ti (instanti) (Fig. 2.2), or in derivatives like ∅ea (instantanea).7

Fig. 2.2 Fribourg, Bibliothèque des Cordeliers, MS 51, fol. 30v (Date: 1364).8

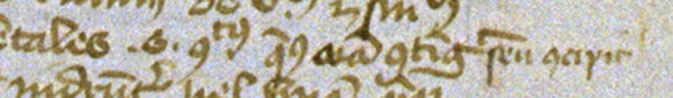

Apart from these special abbreviation marks, which can stand for themselves—there are other, less obvious ones, such as ≈ (esse) or ∻ (est)—the Middle Ages developed a wealth of abbreviation marks that can only be used in combination with letters.9 To start with, there is a three-shaped mark (ꝫ) used for et and for ‘m’ (vertical m), in combination with ‘b’ for ‘bus’ or with ‘q’ for the enclitic ‘que’. A raised nine-shaped mark (ꝰ) is frequently used for ‘us’. A zigzag-shaped mark above a letter (c͛) is used for ‘er’ or ‘re’. A wavelike mark above a letter (c᷈), actually an open ‘flat’ a—the open form being the standard in some medieval scripts such as the Carolingian ‘ꞟ’—often replaces ‘ar’ or ‘ra’ but, generally speaking, it may replace any syllable that contains an ‘a’. A two-shaped mark on top of letters (tꝛ), actually a round r, stands for ‘ur’ or ‘tur’. And the same two-shaped mark on the baseline, combined with a downward stroke, may stand for ‘ris’ as in aꝝles (Aristoteles), though it is more often used at the end for ‘rum’. A dot on or above the baseline after a letter usually signifies a suspension. A horizontal stroke (or two horizontal strokes) above a letter signifies a contraction, which can also be denoted by superscript letters or abbreviation marks.

What we have learned so far allows us to decipher the following abbreviations, all of which are combinations of the letters ‘ca’ with various abbreviation marks: cꝛa (cura), caꝛ (capitur), caꝰ (casus), cā (causa), cāꝫ (causam), ca˭ (causam), cāꝝ (causarum), caꝝ (carum), c͛a (cera), c (charta), c͛

(charta), c͛ (creatura), c͛aꝛ (creatur), and ca· (capitulum, capitulo). On its own, ‘ca’ may also denote a name like Cassiodorus.10

(creatura), c͛aꝛ (creatur), and ca· (capitulum, capitulo). On its own, ‘ca’ may also denote a name like Cassiodorus.10

Abbreviations can be very short, sometimes consisting of a single letter combined with an abbreviation mark. If you know how a particular abbreviation has evolved over time, its various forms are easy to recognize: a arꝫ, a

arꝫ, a aꝫ, a

aꝫ, a ꝫ, apꝫ, and, ultimately, aꝫ have all been used to denote ‘apparet’.11 There are, however, no rules that proscribe reading aꝫ as ‘absolvet’, ‘accidet’, ‘adesset’, or any other word that begins with ‘a-’ and ends with ‘-et’. Since the three-shaped mark (ꝫ) has, as mentioned earlier, various other meanings as well, the word could have a different ending. To make things even more complicated, abbreviations were not only used to represent words but also sometimes replaced whole phrases, which resulted in a reading that could be even more farfetched. For example, in medieval disputations, which are often highly logical, aꝫ is sometimes used to denote ‘maior patet’.12

ꝫ, apꝫ, and, ultimately, aꝫ have all been used to denote ‘apparet’.11 There are, however, no rules that proscribe reading aꝫ as ‘absolvet’, ‘accidet’, ‘adesset’, or any other word that begins with ‘a-’ and ends with ‘-et’. Since the three-shaped mark (ꝫ) has, as mentioned earlier, various other meanings as well, the word could have a different ending. To make things even more complicated, abbreviations were not only used to represent words but also sometimes replaced whole phrases, which resulted in a reading that could be even more farfetched. For example, in medieval disputations, which are often highly logical, aꝫ is sometimes used to denote ‘maior patet’.12

Copying books by hand was a time-consuming task. When Jacobus van Enkhuysen, librarian of the Brethren of the Common Life in Zwolle, produced a copy of the entire Bible in six parchment volumes in folio, it took him 12 years to complete his work.13 Understandably, the scribes sought to ease their gargantuan task by using scribal abbreviations. At the same time, the dignity of the manuscript dictated the extent to which an abbreviation could be used. In precious and ostentatious manuscripts such as the Zwolle Bible, abbreviations tend to be rare or are even entirely absent, with the exception of nomina sacra.14 In academic manuscripts, however, abbreviations tend to be frequent. Even though university lectures were sometimes read “ad pennam”—slowly and accentuated to allow the students to write down the lecture carefully—lecture notes are often hastily written and full of strong abbreviations. This also extends to other texts that were copied and compiled for study purposes.

When a text contained a strong abbreviation for a particular word, even medieval scribes were sometimes at a loss when trying to figure out the correct word. For example, in the very first sentence of a treatise on the soul from the fourteenth century, the copyists came across a strong abbreviation that they successively read as ‘discernere’, ‘discutere’, and ‘disserere’—all of which make sense in the given context.15

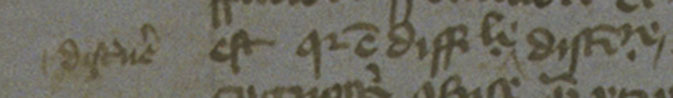

With ambiguities like these, the textual tradition branched out into a multitude of readings. When scribes had access to two or more copies of a particular text, they sometimes added variant readings in the margin or above the line if they were unsure about the correct reading. In a case comparable to the preceding example, the scribe of a commentary on Aristotle’s Physics read ‘distinguere’ (diſtīre) in the main manuscript (“quia est difficile distinguere”) but added ‘discernere’ (diſc͛ne͛) (Plate 2.1) as a variant reading from another manuscript in the margin.16

Plate 2.1 København, Kongelige Bibliotek, MS Ny kgl. Saml. 108 fol., fol. 12ra.

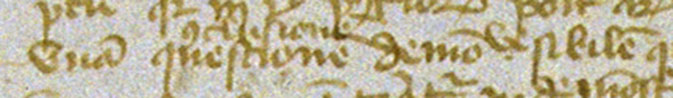

While ‘distinguere’ and ‘discernere’ are largely synonymous, there are other cases where the variant readings change the meaning of the text. For example, it does make a difference whether Aristotle puts forward something as a mere question (quaestio) or as a demonstrative conclusion (conclusio).17 Apparently, at some point in the textual tradition, a scribe misread the nine-shaped abbreviation mark on the baseline for prefixes standing for con-/com- (ⳋ) as the letter ‘q’, the original abbreviation being something like ‘ⳋoꝫ’ or ‘ꝯͦnē’ (conclusionem), which he interpreted as ‘qoꝫ’ or ‘qͦnē’ (quaestionem). The scribe of our commentary read ‘quaestionem’ (queſtionē) (Plate 2.2) in the main manuscript and added ‘conclusionem’ (ꝯcluſionē) as a variant reading from another manuscript above the line.

Plate 2.2 København, Kongelige Bibliotek, MS Ny kgl. Saml. 108 fol., fol. 3va.

In the following example, the original abbreviation may have been something like ‘ꝯit’ or ‘ꝯīt’, which one could read as ‘contingit’ or ‘convenit’, among other possibilities.18 The scribe of our commentary read ‘contingit’ (ꝯtīgt) in the main manuscript, but added ‘concipit’ (ſeu ꝯcipit) as a variant reading from another manuscript in the margin (Plate 2.3).

Plate 2.3 København, Kongelige Bibliotek, MS Ny kgl. Saml. 108 fol., fol. 9vb.

In fact, an abbreviation such as ‘ꝯit’ or ‘ꝯīt’ can have many more readings. Depending on the context, it may also be read as ‘consistit’, ‘constituit’, ‘contigit’, ‘concludit’, ‘convertit’, ‘contulit’, ‘consuevit’, or ‘congruit’, to name but a few options.

It is worthwhile briefly to remind ourselves of how many different readings are possible with a strong abbreviation. Take, for example, the common abbreviation “anֿs”. Looking at this abbreviation through the eyes of a novice reader, “anֿs” may signify any word that starts with the letter a, ends with the letter s, and has the letter n somewhere in between. Searching the Thesaurus Formarum Totius Latinitatis,19 a database of Latin word forms, for instances of “a*n*s” (with the asterisk denoting any string of characters, or no character at all), we get a total of 7,820 results.20 Even when we apply some heuristic rules to narrow down the number of results, the figure is still considerable. For example, we may say that the first two letters (“anֿ”) frequently stand for the preposition ante. When searching for “ante*s” we get 178 results.21 Likewise, we may say that the last two letters (“nֿs”) are frequently used for the ending ens. When searching for “a*ens”, we get 322 results.22

Experience shows that in nine out of ten cases, the abbreviation “anֿs” stands for “antecedens”.23 This, however, cannot be deduced a priori by applying scribal or heuristic rules; it can only be known a posteriori by collating as many instances as possible. In general, one may say that frequently used words or phrases are abbreviated the most. Ultimately, however, only experience can tell what words or phrases are frequent in a given context and which abbreviations were actually used.24

For this reason, collections of abbreviations have been compiled from the earliest days.25 In the late Middle Ages, more and more lists of abbreviations were put together.26 This is unsurprising, since both the sheer volume of texts and the number of abbreviations used increased significantly during the thirteenth, fourteenth, and fifteenth centuries. In the age of printing, the anonymous Modus legendi abbreviaturas in utroque iure was reissued many times over.27 The first edition of this book was probably printed in Cologne around 1475, and subsequent editions were published in Basle, Strasbourg, Nuremberg, Louvain, Paris, and elsewhere.28 It was reprinted continuously until 1623.29 In the sixteenth century, we have the Nuova regoletta nella quale troverai ogni sorta de abbreviatura usuale,30 which contains around 900 abbreviations, and Manutius’ De veterum notarum explanatione quae in antiquis monumentis occurrunt.31

In the eighteenth century, the first attempts were made to devise a comprehensive collection of abbreviations. Daniel Eberhard Baring published his Clavis diplomatica in 1737,32 followed by Johann Ludolf Walther’s Lexicon Diplomaticum in two volumes in 1747.33 In the late nineteenth century, two major dictionaries of Latin abbreviations were compiled. The first was Alphonse Chassant’s Dictionnaire des abréviations latines et françaises in 1846, which was corrected and augmented several times;34 the second was Ramón Álvarez de la Braña’s Siglas y abreviaturas latinas in 1884.35

Still in use today is Adriano Cappelli’s Lexicon abbreviaturarum. It first appeared in 1899 as part of the series “Manuali Hoepli.”36 It has since been revised four times, twice in Italian for the same series (1912, 1929) and twice in German for “Webers illustrierte Handbücher” (Leipzig 1901, 1928).37 A longer version of the Latin title was used in 1899—Lexicon abbreviaturarum quae in lapidibus, codicibus et chartis praesertim medii-aevi occurrunt—but all subsequent editions have reduced the title to two words, following the example of the German translator: Lexicon abbreviaturarum: Wörterbuch lateinischer und italienischer Abkürzungen. The first Italian edition contained 10,000 entries, and although a further 3,000 entries were added in the German translation of 1901, the next Italian edition in 1912 was enlarged by only a thousand entries; its present size stands at approximately 14,000 entries. Since 1929 no changes have been introduced into the Italian text, which continues to be reprinted under the title Lexicon abbreviaturarum: Dizionario di abbreviature latine ed italiane usate nelle carte e codici specialmente del medio-evo riprodotte con oltre 14000 segni incisi con l’aggiunta di uno studio sulla brachigrafia medioevale, un prontuario di Sigle Epigrafiche, l’antica numerazione romana ed arabica ed i segni indicanti monete, pesi, misure, etc.38

The Lexicon was never available in an English edition, as it was in German, but Cappelli’s prefatory treatise on the elements of Latin abbreviation has been published in an English translation under the title The elements of abbreviation in medieval Latin paleography by Adriano Cappelli, Lawrence, Kansas 1982.39

Auguste Pelzer’s Abréviations latines médiévales: Supplément au Dizionario di abbreviature latine ed italiane de Adriano Cappelli presents a valuable supplement based on Vatican manuscripts.40 It contains approximately 1,500 entries that cannot be found in Cappelli.

According to Adriano Cappelli’s Lexicon abbreviaturarum, all medieval abbreviations can be divided into six categories (some of these abbreviation techniques are still in use today).

1. Truncation. A word is abbreviated by truncation when only the first part of the word is actually written out, while an abbreviation mark replaces the missing final letters. Examples are: b. (beatus), a.t. (alia translatio), fi· (fide), and oꝭ (omnis). Today, only the dot on the baseline has survived in abbreviations of titles, such as Prof. (Professor), and in commercial abbreviations as part of firm names such as Co. (Company), Corp. (Corporation), and Inc. (Incorporated).

2. Contraction. A word is abbreviated by contraction when one or more of the middle letters are missing. Such an omission is indicated by one of the general signs of abbreviation: ſpֿſ (spiritus), grֿa (gratia), roֿ (ratio), and anֿs (antecedens). Today, we frequently use contractions, but usually without any sign of abbreviation, in abbreviations such as Mme (Madame) and Mlle (Mademoiselle) in social titles, or in the last part of street names such as Blvd (boulevard), Pkwy (parkway), and Rd (road).

3. Abbreviation marks significant in themselves. These signs indicate which elements of the abbreviated word are missing, no matter what letter the symbol is placed above or joined with as a ligature. Examples are: ꝓ (pro), ꝓbō (probatio), ꝓbale (probabile), and ꝓlogꝰ (prologus).

4. Abbreviation marks significant in context. In this category are signs that indicate which elements are missing in an abbreviated word whose meaning is not set and constant but varies relative to the letter for which the sign stands. Examples are: ꝑ (per), ꝑfcō (perfectio), ꝑcial’ (partialis), and ꝑcio (portio).

5. Superscript letters. With a few exceptions, a word is abbreviated with superscript letters at the end of a word where a superscript letter, whether a vowel or a consonant, simply indicates the ending of the word. Examples are: ad (aliud), aa (maior nota), gͤci (Graeci), and ꝓꝓpiete (proprietate). Today, we use abbreviations such as nº (numero/number) as well as in ordinal numerals such as 1st, 2nd, 3rd, and 4th.

6. Conventional signs. This category includes all signs that stand for a frequently used word or phrase; in most cases these are not recognizable as letters and they are almost always isolated. Examples are: ≈ (esse), ≈nr (essentialiter), ∅ (instans), and ∅ti (instanti). Today, our currency symbols €, £, $, and ¥ fall into this category as do Ⓡ (registered trademark) and © (copyright), as well as many conventional signs in the sciences that are not recognizable as letters such as ×, ÷, =, ≠, ≈, ∅, ⊕, ⊗, ∞, and so on.

It should be noted that not all medieval abbreviations start with the initial letters of the words they represent. Examples include l’ (vel), ·n· (enim), go (ergo), and gi (igitur). As our examples illustrate, it should be noted that the six categories discussed here are not mutually exclusive.

There were no restrictions on which techniques could be used to abbreviate a particular word. For example, the word ‘consequentia’, a frequent word in logical argumentations, has been abbreviated variously as: ꝯ᷈, ꝯa, ꝯn᷈, ꝯna, ꝯnֿa, ꝯn˭a, ꝯnֿcia, ꝯſeꝗa, ꝯſequētia, con˭a, and conֿcia.

It remains a matter of debate whence exactly these different abbreviation techniques originated. Contraction, for example, which is clearly the most frequently used abbreviation technique in late-medieval manuscripts, can be traced back to the abbreviation of nomina sacra, which in turn can already be found in early Greek Christian manuscripts.41 The most common of these abbreviations are: ΘΣ = θεός, ΚΣ = κύριος, ΙΣ or ΙΗΣ = Ἰησοῦς, ΧΣ or ΧΡΣ = Χριστός, and ΠΝΑ = πνεῦμα. Following the Greek example, these abbreviations were written in Latin texts as D̅S = Deus; DN̅S or DM̅S = Dominus; IH̅S = Iesus; XP̅S = Christus; and SP̅S = Spiritus. These Latin abbreviations sometimes imitated the Greek letters by using visually similar letters from the Latin alphabet.42 The origin of the usage of contracting the nomina sacra, however, remains unclear to this day. The Christian scribes may have received their inspiration from the Jewish tradition of writing the inexpressible tetragram in the Greek versions of the Old Testament, or, alternatively, from a similar usage of writing the names of emperors in Greek cursive script.43

It can be useful to be aware of the fact that some abbreviations originated in the British Isles, while others were invented (and frequently used) in Spain or on the Italian Peninsula. In Italy, for example, ‘qui’ was represented by a distinctive abbreviation, written with a horizontal stroke through the descender of the letter q.44 This abbreviation was also used in combinations, such as ‘ꝗa’ (quia), ‘ꝗdē’ (quidem), or ‘aliꝗd’ (aliquid). Thomas Aquinas used this abbreviation in his own handwriting, the famous “littera inintelligibilis” as it was dubbed by contemporaries,45 which, however, is only ‘illegible’ as far as Thomas’s script is concerned, while the abbreviations used are not exceptionally difficult to decipher.46

Notably, however, scholars traveled, and so did their books and their abbreviations. A scribe who, like Thomas Aquinas, was trained in Naples, Italy did not immediately change his abbreviation techniques when he traveled to Paris and started to copy manuscripts there. Hence, we should be careful not to use abbreviations as the sole instrument in dating or locating a particular manuscript, even though they are undoubtedly useful as additional evidence.

Little is known about scribal training in the use of abbreviations. It should thus be all the more worthwhile briefly to look at one of the rare examples of a medieval tutorial for novice scribes. Our example is special in that it is an attempt to reform scribal practice, which apparently had got somewhat out of hand. The multitude of abbreviations in use during the Late Middle Ages had become a danger when it came to the transmission of religious texts. If a text is considered to be holy, as in the case of the Holy Scripture, it is naturally of the utmost importance that every single word is transmitted correctly. There must not be the slightest doubt as to what word the scribe has copied. It is certainly no coincidence that the Congregation of Windesheim, where this tutorial was compiled in the late fourteenth or early fifteenth century, prepared, at around the same time, a critical revision of the Latin Bible (Vulgate).

The title of the treatise as given in the Incipit reads as follows: “Quaedam regulae de modo titulandi seu apificandi pro novellis scriptoribus copulatae.”47 This title introduces us to some technical terms related to the art of abbreviating. The term ‘titulare’ literally means ‘to add a titulus to a letter’. The term ‘apificare’ is used as a synonym and literally means ‘to add an apex to a letter’.

At the beginning of the text, the terms ‘titulus’ or ‘titellus’—the text does not use the term ‘apex’—refers to the abbreviation strokes placed on top of letters to indicate contraction. Later on in the treatise, however, the term is also used to refer to other abbreviation marks. We may thus readily say that ‘titulus’ or ‘titellus’ refers to any sign that is used to indicate an omission.

Since the text is aimed at novice scribes, the abbreviation rules are fairly simple. Usually, only individual syllables are abbreviated. Hence, the term ‘syllabicare’ is used in an alternative title of the treatise given in the initial table of contents: “Quaedam regulae scribendi et syllabicandi bonos libros”.

As this second title makes clear, the collection of scribal rules should be used to copy ‘good books’, which the text of our treatise identifies further as ‘precious books, that is to say, Bibles and the like’ (iste modus titulandi servari potest in libris pretiosis, scilicet in bibliis et huiusmodi). However, the scribe may, if he so wishes, also apply these rules to the writing of missals, sermons, or homilies (nisi scriptori autem placuerit, scilicet in messalibus, sermonibus, homilariis et sic de aliis).

The scribal rules of the treatise are straightforward: special rules refer to syllables at the beginning of words (rules 1–3), at any position within a word (rules 4–5), or at the end of a word (rules 6–9 and 12). A special case refers to polysyllabic words (rule 13) where every single syllable is “titellabilis”, i.e., where every syllable can be abbreviated with a “titulus”; in such cases, one needs to determine which syllables should be abbreviated. Two general rules (rules 14–15) determine when and where the ‘titulus’ has to be placed in order to avoid doubt in the reader. Finally, three rules (rules 10, 11, and 16) refer to when and where to use special letterforms: the round u, the round r, and the long s.

As an example, let us look at two general rules that aim at avoiding ambiguity in abbreviation.

Rule 14. Every “titellus” must always be placed exactly where it replaces a number of characters; otherwise, it raises doubt in the reader and also often changes the meaning of the word, as is evident in the following example: If in “rapia” the “titellus” is put directly over the a (rapiā), this signifies a verb and is read as “rapiam”. If, however, the “titellus” is put directly over the i (rapīa), this signifies a noun and is read as “rapina”. For this reason, the “titellus” must be put in the exact place where it replaces a number of letters (suppletio) or where it modifies the meaning of a letter (combinatio). For example, when using a “titellus” in writing “gratia” or “littera”, the “titellus” must not be placed over the last letter, but instead over the middle letter (gr̵a, lr̵a). Likewise, in ‘frēs’ (fratres) and ‘pꝛēs’ (patres), the “titellus” must be put over the r as in ‘fr̵e’ (fratre) and ‘pꝛ̄e’ (patre).`

Rule 15. If a “titellus” allows us to read a word in various ways, then it must not be written with a “titellus”, as in the examples provided, for these can be read in two ways: ‘cōfo᷈ꝛre’ (“confortare” or “conformare”), ‘tꝑare’ (“temperare” or “temporare”), ‘gēitus’ (“genitus” or “gemitus”), and so forth. This general rule drastically reduces the number of abbreviations. Here, as well as in other places, the treatise emphasizes that an abbreviation must not generate any doubt in the reader; if there is the slightest possibility of doubt concerning the “significatum dictionis” (i.e., the meaning of a given abbreviation), the word must not be abbreviated. Strong contractions are only allowed for well-known and frequently used abbreviations signifying words such as dominus, Deus, gratia, littera, ecclesia, fratres, patres, and so forth. Ambiguity in abbreviations must be avoided at any cost in order to make sure that the texts of precious books, that is to say, Bibles and the like, are transmitted correctly.

Despite such late-medieval attempts to reform scribal practice, the reader of a medieval Latin manuscript usually has to solve a three-dimensional puzzle: one has to read a text in a foreign language (medieval Latin), which is written in an unfamiliar script, and, on top of that and more often than not, which is heavily abbreviated. The three dimensions are tightly interconnected: if you cannot recognize a letter in a particular script, you may have a hard time deciphering the abbreviation used; likewise, if you do not know the many technical terms of medieval Latin, you may have no idea what a particular abbreviation stands for. If you are an expert in Latin palaeography, and widely read in a particular field, you will probably have a good idea of what a given abbreviation stands for; this intuitive knowledge can, however, sometimes be misleading. Solving the compound puzzle presented by medieval Latin manuscripts is both an art and a science. Fortunately, Latin palaeography is becoming more of a science today.

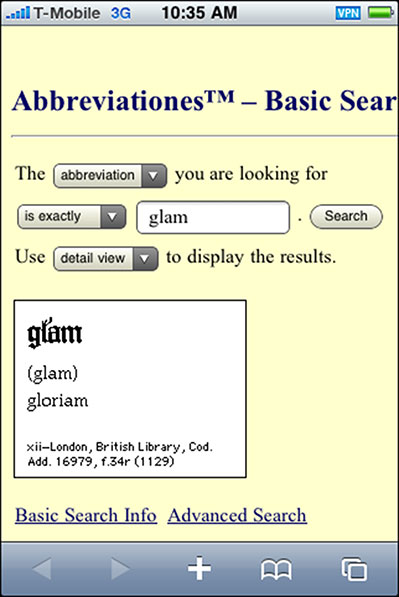

The humanities have become more and more computational in recent years, and Latin palaeography is no exception. The first database of medieval Latin abbreviations, aptly named “Abbreviationes™,” was developed by Olaf Pluta at Ruhr-Universität Bochum, Germany.48 Originally written for the Apple Macintosh family of computers, the database is now published exclusively on the Internet, following the long-term trend away from native applications to web-based applications (“cloud computing”).49 Today, you can access Abbreviationes™ from anywhere with an Internet connection and a web browser, even from your smartphone (Plate 2.4). A medieval scribe would certainly be amazed at the ease and speed with which a current reader can today search for abbreviations on a small handheld device, tapping on a mirror-like surface where letters and abbreviation marks appear as if by magic.

Plate 2.4 Abbreviationes™ on the Apple iPhone 3G.50

And th@’s th@!

Notes

ae͛t’. Apart from aꝫ, frequent abbreviations of this type include dꝫ (debet), eꝫ (esset), hꝫ (habet), lꝫ (licet), oꝫ (oportet), pꝫ (patet), ſꝫ (scilicet), tꝫ (tenet), and vꝫ (valet, videlicet).

ae͛t’. Apart from aꝫ, frequent abbreviations of this type include dꝫ (debet), eꝫ (esset), hꝫ (habet), lꝫ (licet), oꝫ (oportet), pꝫ (patet), ſꝫ (scilicet), tꝫ (tenet), and vꝫ (valet, videlicet).