Chapter 7

Uncial Script

Uncial is the name used today by Latin palaeographers to designate a type of bilinear, rounded, majuscule book script that is especially distinguished from other ancient majuscule scripts (e.g., Rustic Capital) by the forms of the letters A ( ), D (

), D ( ), E (

), E ( ), and M (

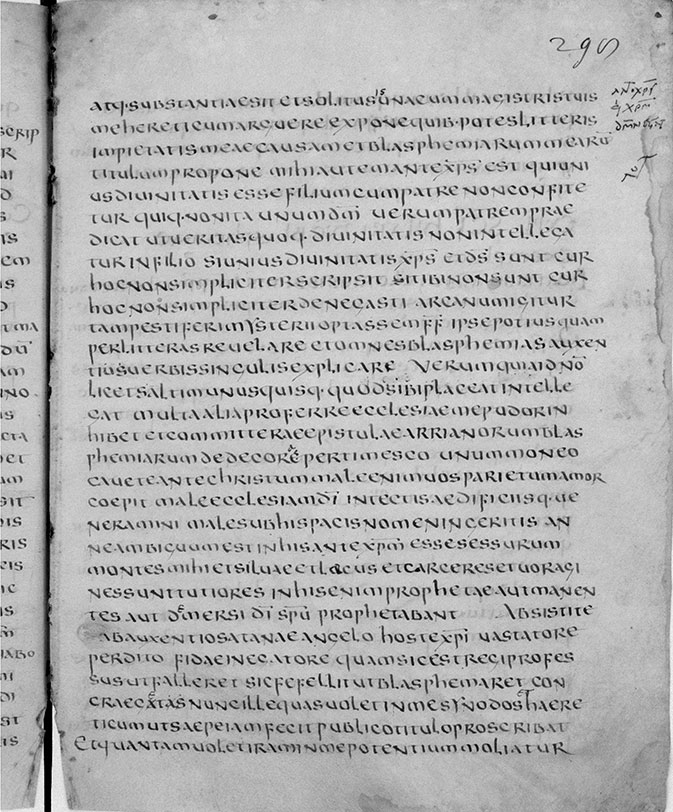

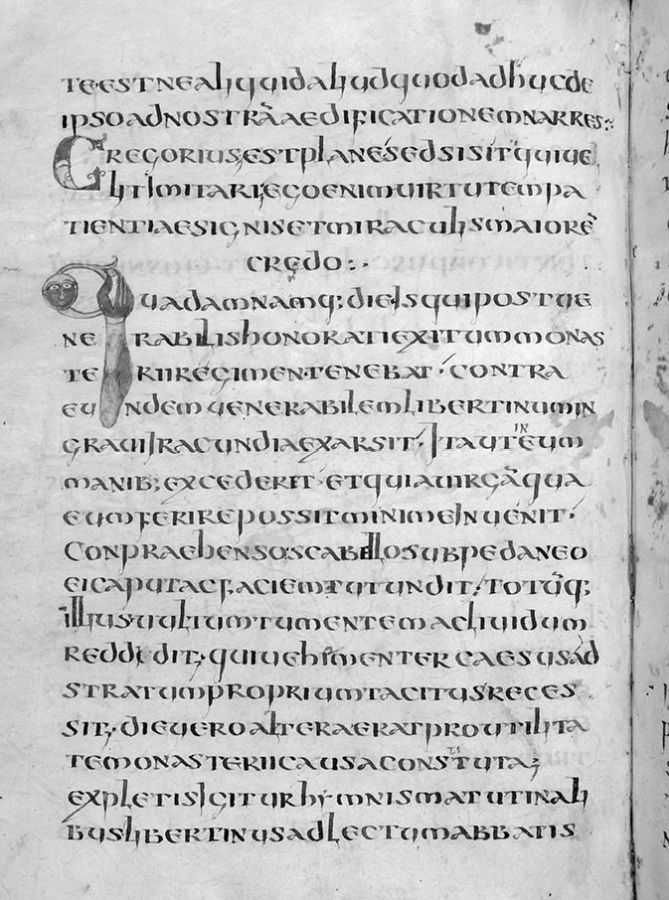

), and M ( ).1 A classic example of Uncial script is the Basilicanus of Hilary (Plate 7.1; Vatican, Arch. Cap. S. Pietro, D. 182, fol. 298; CLA 1.1b). Uncial script is not, in the strictest sense, entirely bilinear (that is, written between two lines); but in the early examples very few letters (e.g., d, h, l, p, and q) have ascenders or descenders, and these are typically rather short, so the script has a predominantly bilinear appearance. Later examples of the script can exhibit much longer ascenders and descenders, and more letters have them (including b, f, g, and r), giving the script a more quadrilinear aspect. Early Uncial script—that is, the script of the fourth or fifth centuries—is distinguished by a writing angle of 45–50o. Beginning in the sixth century, an angle of writing of 90o becomes common for the Uncial hand. Whatever the angle, the heavy shading of the script remains a constant feature; in other words, there is a marked difference between the thick and thin strokes within a letter. More than four hundred books or fragments written in Uncial script survive, dating from the fourth to the ninth centuries; and Uncial continued to be used in later periods as a display script (and for colophons, running heads, titles, etc.) after it had ceased to be used as a text script. The use of Uncial as a display script has been relatively neglected and warrants a more extensive study.

).1 A classic example of Uncial script is the Basilicanus of Hilary (Plate 7.1; Vatican, Arch. Cap. S. Pietro, D. 182, fol. 298; CLA 1.1b). Uncial script is not, in the strictest sense, entirely bilinear (that is, written between two lines); but in the early examples very few letters (e.g., d, h, l, p, and q) have ascenders or descenders, and these are typically rather short, so the script has a predominantly bilinear appearance. Later examples of the script can exhibit much longer ascenders and descenders, and more letters have them (including b, f, g, and r), giving the script a more quadrilinear aspect. Early Uncial script—that is, the script of the fourth or fifth centuries—is distinguished by a writing angle of 45–50o. Beginning in the sixth century, an angle of writing of 90o becomes common for the Uncial hand. Whatever the angle, the heavy shading of the script remains a constant feature; in other words, there is a marked difference between the thick and thin strokes within a letter. More than four hundred books or fragments written in Uncial script survive, dating from the fourth to the ninth centuries; and Uncial continued to be used in later periods as a display script (and for colophons, running heads, titles, etc.) after it had ceased to be used as a text script. The use of Uncial as a display script has been relatively neglected and warrants a more extensive study.

Plate 7.1 Vatican, Arch. Cap. S. Pietro, D. 182, fol. 298r; CLA 1.1b (Hilary): probably Cagliari, Sardinia, saec. VIin (post 509–10) © 2015 Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana.

The Uncial script is sometimes said to have been particularly favored for Christian texts.2 It is certainly the case that the surviving manuscripts in Uncial script predominantly contain Christian works, and those in Rustic Capital script, pagan. To what extent the surviving evidence reflects an intentional choice of script on the part of Late Antique scribes or patrons is less clear. The monumental study by Chatelain, in spite of needing updating in many respects, is the starting place for any investigation of Uncial.3 The various volumes of Lowe’s CLA (along with the supplements to the series) provide a comprehensive listing of the surviving specimens and succinct descriptions of them.4

The Latin adjective uncialis means “of one ounce” or “of one inch.” The term Uncial was introduced to modern scholarship by Jean Mabillon, although he uses it in a broader sense for a variety of types of majuscule script.5 The source of the name is a passage in Jerome: “Those who want them can have their old books, or those inscribed on purple skins with gold and silver, or executed in what are commonly called ‘Uncial letters’—burdens more than codices.”6 Since Jerome is describing, albeit hyperbolically, luxury books of his day that were written in large (or weighty) letters, some readers have assumed that he is talking about a specific type of majuscule script known in his day by the name “Uncial.” It is unclear whether Jerome is referring to the size of the letters or the weight of gold or silver used to produce them (or both), although by labeling the books “burdens” he may intend to emphasize the weight of the letters as well as of the volumes. Precisely what type of script Jerome has in mind is not clear from the passage, and it is debatable whether he is even referring to a specific type of script, rather than to the enlarged letters that appear at the beginning of each page in books like the Vergilius Augusteus.7 But the name Uncial has stuck, and since its use by modern palaeographers to describe one particular script type is relatively consistent and specific, there seems little reason to abandon it.

The origins of the script are unclear because of the paucity of surviving Latin manuscripts before the fourth century that are written in book scripts; but Uncial may be described as a descendant of Roman capital script, under cursive influence. The latter contributed to the roundness of the script as well as to specific letterforms (e.g., a, e, d, and m).8 By the fourth century, Uncial is a well-developed script, apparently the product of many generations of evolution and refinement. Earlier specimens of Latin book scripts, for example the fragment of “De bellis Macedonicis,”9 illustrate this developmental stage with their mixture of letters in Rustic Capital, Uncial, Half-uncial, and cursive forms. Such mixed scripts must have been common, and the occasional mingling of elements from other scripts is still found in some of the earliest Uncial manuscripts, as also in some of the later regional types of Uncial (e.g., the b-d Uncial mentioned below).

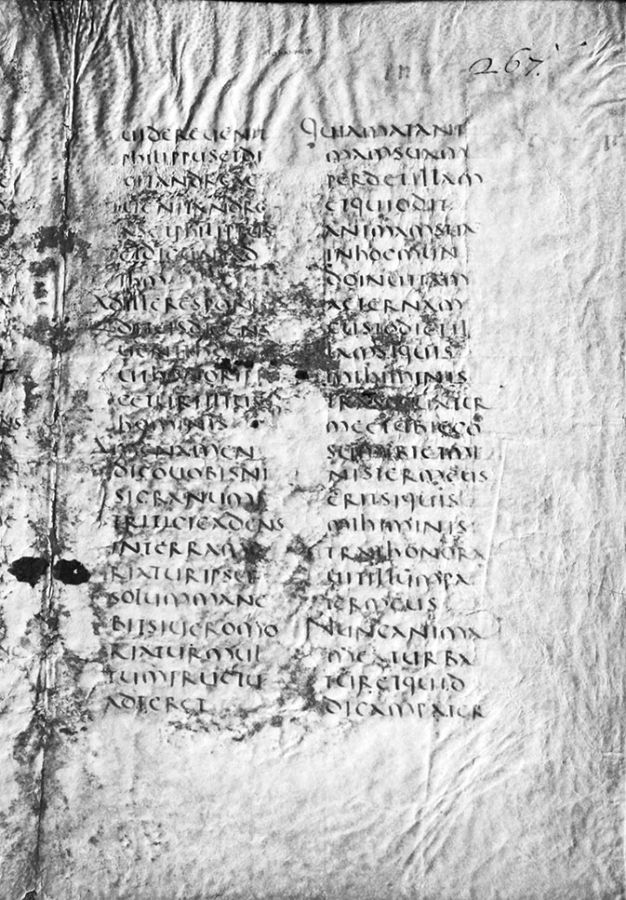

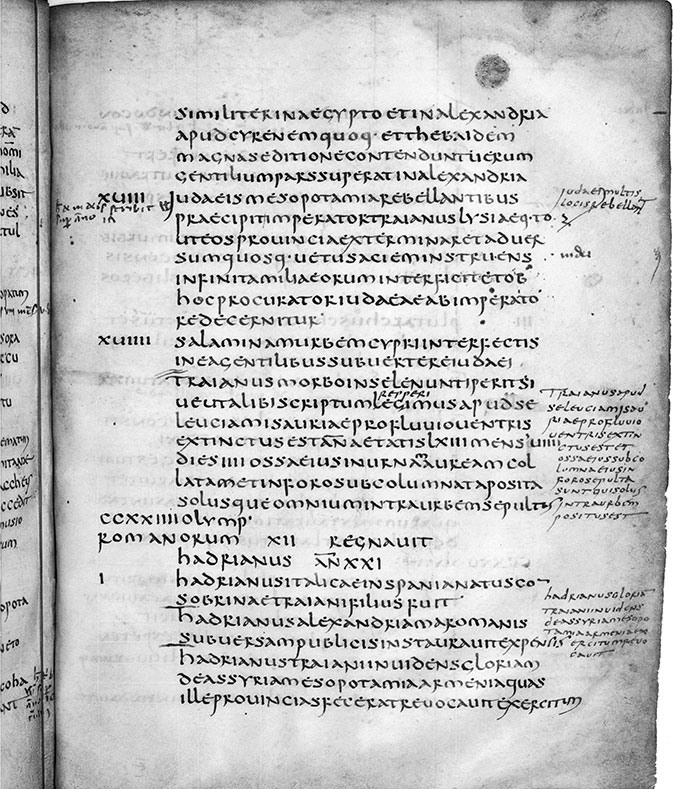

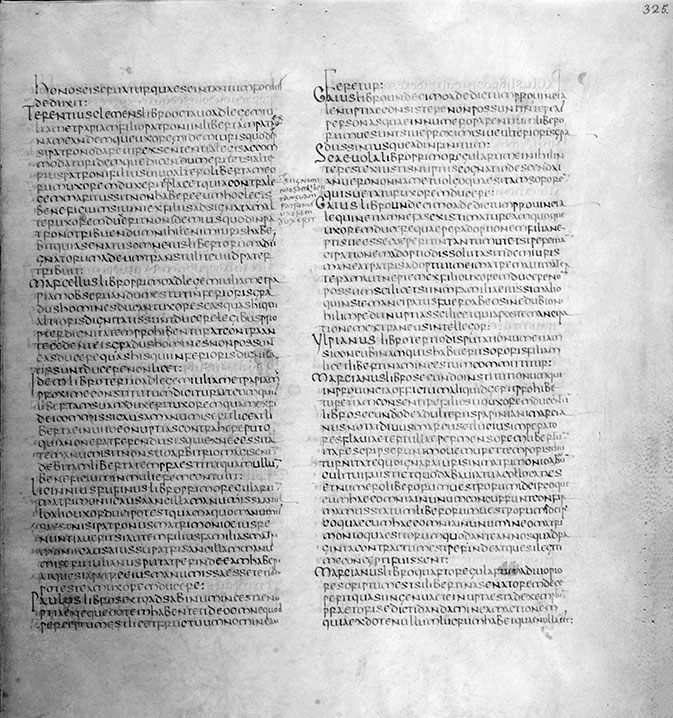

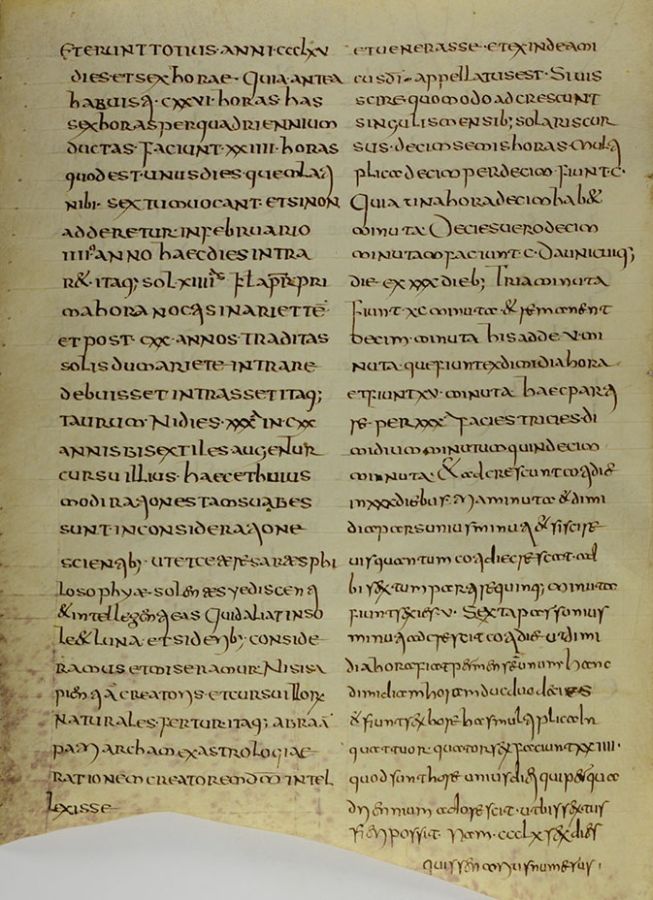

Dated examples of Uncial writing are extremely rare; but a sufficient body of material from the period between the fourth and the eighth centuries has been preserved to allow, in conjunction with the evidence from the few dated or datable examples, a rough dating of the surviving specimens.10 The major guideposts for dating Uncial, in chronological order, are the Codex Vercellensis of the Gospels, c.371 (Plate 7.2; Vercelli, Biblioteca Capitolare, s.n., fol. 267; CLA 4.467), the Bodleian manuscript of Jerome’s Chronicle, after 435 or 442 (Plate 7.3; Oxford, Bodleian Library, Auct. T. II. 26, fol. 121; CLA 2.233a), the Berlin Easter Tables, 447, (Berlin, Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, Lat. qu. 298; CLA 8.1053;), the Basilicanus of Hilary, after 509/510 (Plate 7.1; CLA 1.1b), the Codex Pisanus of Justinian, after 533 (Plate 7.4; Florence, BML, s.n., vol. 1, fol. 325r; CLA 3.295), the Codex Fuldensis of the Gospels, before 546/547 (Fulda, Landesbibliothek, Bonifatianus 1; CLA 8.1196), the Toulouse Canons, 666/667 (Toulouse, Bibliothèque municipale, 364 + Paris, BnF, Lat. 8901; CLA 6.836), the Morgan Augustine from Luxeuil, 669 (New York, Pierpont Morgan Library, M. 334; CLA 11.1659), the Bern manuscript of Jerome’s Chronicle, 699/700 (Bern, Burgerbibliothek, 219; CLA 7.860), the Brussels collection of Varia Patristica from Soissons, 695–711 (Brussels, Bibliothèque Royale, 9850–2; CLA 10.1547a), the Codex Amiatinus of the Bible, 681–716 (Plate 7.5; Florence, BML, Amiatino 1, fol. 1006v; CLA 3.299), the Trier Quodvultdeus, 719 (Trier, Stadtbibliothek, 36; CLA 9.1367), the Milan manuscript of Gregory’s Moralia, around 750 (Plate 7.6; Milan, Biblioteca Ambrosiana, B. 159 sup., fol. 14v; CLA 3.309), the Autun Gospels, 754 (Autun, Bibliothèque municipale, 3 (S. 2); CLA 6.716), the Codex Beneventanus of the Gospels, 736–60 (London, BL, Add. MS 5463; CLA 2.162), and the collection of texts in Lucca 490, after 787 (Plate 7.7; Lucca, Biblioteca Capitolare, 490, fol. 322v; CLA 3.303e).11

Plate 7.2 Vercelli, Biblioteca Capitolare, s.n., fol. 267r; CLA 4.467 (Codex Vercellensis of Gospels): Italy, saec. IV2 (c.371).

Plate 7.3 Oxford, Bodleian Library, Auct. T. II. 26, fol. 121r; CLA 2.233a (Jerome’s Chronicle): Italy, saec. Vmed (post ad 435 vel 442).

Plate 7.4 Florence, BML, ms. Pandette s.n., cassetta 1, fol. 325r; CLA 3.295 (Codex Pisanus, Justinian): Byzantium, saec. VI (soon after 533).

Plate 7.5 Florence, BML, Amiatino 1, fol. 1006v; CLA 3.299 (Codex Amiatinus of Bible): Wearmouth or Jarrow, saec. VII–VIII (ante ad 716).

Plate 7.6 Milan, Biblioteca Ambrosiana, B. 159 sup., fol. 14v; CLA 3.309 (Gregory, Moralia): Bobbio, saec. VIIImed (c.749).

Plate 7.7 Lucca, Biblioteca Capitolare, 490, fol. 322v; CLA 3.303e (Bede): Lucca, saec. VIII–IX (post 787).

Scholars have identified and described regional variations of the Uncial script that were used in Italy,12 North Africa,13 England,14 France,15 and the Eastern Empire (Byzantium?).16 Only from Italy is there surviving material from all periods of the writing of Uncial script; elsewhere, the extant evidence comes from comparatively short periods of production (so, e.g., the North African examples are predominantly from the fourth and fifth centuries, the French from the seventh and eighth). Consequently, the localization and the dating of Uncial manuscripts are intimately connected.

Lowe’s naming of the varieties of Uncial script, which can serve to isolate distinct regional and chronological groupings, is primarily based on the Basilicanus of Hilary (CLA 1.1b; Plate 7.1). The forms of the letters in that manuscript are taken by him to be canonical for Uncial script, and variant types are described in terms of their deviations from it.17 So, for example, “b-uncial” has generally the letterforms found in the Basilicanus, with the exception of the b, which has the minuscule (or Half-uncial) form; “b-d Uncial” has the Basilicanus forms except for its use of minuscule (Half-uncial) b and d. More work needs to be done in defining stylistic groupings among the surviving manuscripts.