Chapter 46

The Book Trade in the Middle Ages

The Parisian case

Discussing the book trade in the Middle Ages not only means looking at the object—the codex—from a commercial perspective, but also keeping in mind its cultural and social functions. For specialized artisans, trading in books could provide privileges which testified to their participation in more than simple trading activities. Book commerce, by virtue of dealing with the written word, brought to medieval craftsmen a distinctive character and an increased social status.1 As M. T. Clanchy points out, “by elaborating the sacred page of Scripture, monks had sanctified writers as much as books.”2 The medieval book trade and its actors are well researched for cities like Paris, which will provide the case study of this essay.

From Monasteries to Universities

Western culture and its emphasis on Scripture first reserved book production for the monk: the rule of Saint Benedict designated lectio as a divine service, while prominent abbots devoted energy to the developing of scriptoria in their abbeys. So it is no surprise that, according to the research of C. Bozzolo and E. Ornato for northern France, the growing production of books starting in the tenth century mainly concerned religion (Latin biblical, patristic, theological, and hagiographical manuscripts represented 80% of all books produced).3 Until the early thirteenth century, the growth in the number of books was a response to the multiplication of monastic foundations and not to a diversification of subject matter. After 1200 the typology of manuscripts changed to reflect cultural evolution: Latin religious texts declined to a proportion of 50%, giving way to a multiplication of university manuscripts (philosophy, law, medicine) and lay vernacular works (romances, history, etc.).

Educational institutions, and especially universities, multiplied in thirteenth-century Western Europe, feeding a need for more books. As the number of students and masters steadily grew, so did the demand for writing and reading materials. This phenomenon was accompanied by the development of an urban culture which saw, by the end of the century, the written word spread—both in Latin and in the vernacular—to new social groups. A new type of urban-based book trade emerged in response to the needs of scholars and aristocrats.

Teaching created an exploding demand for multiple copies which was met by an original mode of book production, the pecia system. As first described by Jean Destrez in 1935, this system allowed medieval colleges and universities to offer manuscripts for copy by multiple scribes at the same time.4 The time involved in copying was indeed the main obstacle to fast production. According to best estimates, a 200-folio bound manuscript would have taken a lonely scribe almost 7 months to complete.5 Under the pecia system, universities authorized booksellers—generally called stationarii—to keep copies of unbound manuscripts (exemplaria) in the form of a series of inspected quires or pieces of manuscript (peciae) and to rent them at a fixed price (taxatio). The stationer entered his prices in a taxation list and rented the quires one by one to potential scribes who would copy a quire, bring it back, rent the next one, etc. The copy was not necessarily made in the original order of the peciae, but the scribe kept a note of his progress by indicating in the margins of his work which pecia he copied, or by leaving space to write later the content of a quire used by some other scribe. Once all the quires were copied, a new manuscript was created. Although it required care and good planning from the scribe, the advantage of such a system was obvious: it allowed as many scribes to work on a book as there were quires composing it. In the case of a 200-folio work composed, for example, of 17 peciae of 12 leaves each (the standard format for a pecia in most universities), the copy would still take almost 7 months for each individual copy, but in that time period 17 scribes could work simultaneously to produce 17 different copies of the original exemplar. The pecia system was implemented under the control of universities for their members, starting c.1250, mainly in Italian cities like Bologna, Padua, Perugia, Naples, or Florence, but also in Paris, Orleans, Toulouse, Montpellier, and Salamanca. It declined after a century of existence, when the demographic collapse removed the pressing need for more scholarly books and when the multiplication of libraries, either personal or in colleges and convents, gave access to books previously individually owned. By the mid-fourteenth century, a large number of what we would call “secondhand” books were circulating and feeding the university book trade. It did not, however, stop universities from keeping a more or less careful eye on suppliers of books.

Controlling the Book Trade

The production and sale of books in Paris involved a variety of craftsmen, including parchment or paper makers, illuminators, bookbinders, booksellers, and scribes. The latter are difficult to identify, since many academics and clerics copied books for themselves and were occasionally paid to do so for others without being designated as professional book writers. Only in some exceptional late medieval cases is it possible to recognize an écrivain mentioned several times as a scribe working for another person, a patron or a bookseller. By the early fifteenth century, there lived in Paris and London specialized book copyists, distinct from scribes writing deeds and other legal or administrative documents. They identified themselves differently, as écrivains de lettres de forme (text writers) who worked on the production of manuscripts, as opposed to the écrivains de lettres de cour (writers of court letters or scriveners) who were working for various tribunals and administrations.

In 1275, the University of Paris took a first step in regulating the book trade in order to protect masters and students from allegedly greedy merchants. University officials pleaded for “just and legitimate prices,” limiting the profit made from the sale of a book to 1.7% of its selling price and establishing the renting price of peciae. Two decades later, parchmenters were invited to demonstrate honest practices when selling skins to university members. The university did not attempt to control illuminators or bookbinders whose activities were not as essential to university members as was access to books and parchment. Booksellers and parchmenters, on the other hand, had to take an oath of obedience and to swear to respect university regulations to be allowed to do business with masters and students. Refusal to comply was met with boycotts, fines, and loss of clients from the university. In exchange for their oath, these craftsmen were designated as university members (suppositi), a status which permitted them during the whole of fourteenth century to benefit from a series of fiscal exemptions.

University rules which dealt with librarii and pergamenarii of Paris at the end of the thirteenth century were in fact targeting all members of the book trade. The first privilege granted in 1307 addressed only booksellers and parchmenters, but it released every book craftsman from future fiscal records. Under the term librarii the whole trade was therefore understood, which suggests the prominent role of the bookseller among the other crafts and the strong link existing between them.

The university certainly had a powerful tool in hand at the beginning of the fourteenth century to impose its rule on the selling and production of manuscripts. Punishments for disobedience were real threats to craftsmen of books. In 1313 booksellers went on strike, refusing to swear the oath. They complied after only a few weeks, when they successfully negotiated more autonomy. Their protest led to the creation of four masters of the trade (magni librarii) in charge of inspecting the exemplaria and of making booksellers obey university rules. By the beginning of the fifteenth century, however, in spite of extended fiscal privileges which set these artisans apart from Parisian craftsmen, and in spite of threats of losing their advantageous situation, the university was no longer able to impose its control. Numerous reminders of the regulations, along with vain attempts to exclude offending artisans from the university ranks, suggest that booksellers and parchmenters were not always faithful to their oath. Book producers and merchants no longer feared the university, for they also served the growing needs of a widening literate population, lay or clerical, in Latin and in the vernacular.

At the dawn of the fifteenth century the university was unable to claim an oath from booksellers as it had done for decades. Moreover, the University of Paris was unable to convince royal authorities that those artisans—some of whom were illiterate, some of whom abused their position by exercising various other trades, while most did not care about university regulations and on whom the university could impose nothing because they did not work mainly for university members—were legitimately exempt from taxation in the name of their academic status. After almost a century of debate between the university and royal officials, in a context of a contested institution with declining authority, the king decided to limit the number of book craftsmen benefiting from university privileges. After 1489 in Paris, the only artisans with academic status were 24 booksellers, 4 parchmenters, masters of their trade (maistres jurez), 4 paper venders, 7 paper makers from outside the city, and 3 trade masters each for the illuminators, the bookbinders, and the book writers. All the others were to fall back under the authority of the royal provost in charge of all trades and crafts in the capital, and to bear normal fiscal burdens. The royal ordinance put an official end to university control over booksellers and parchmenters.

A Tightly Bound Community

Research of the last 20 years has demonstrated that university rules could be misleading if taken at face value. Since booksellers could also be bookbinders or illuminators, since parchmenters could become stationarii, or writers be illuminators and booksellers, there was clear evidence that many more crafts were affected by those regulations than had been thought in the past. The need to examine all members of the trade became obvious. It led in turn to a new understanding of the organization of crafts and finally to new hypotheses on book production.

A study of the location of book craftsmen in medieval Paris reveals concentrations which evolved over time, a phenomenon also visible in London.6 In Paris, the earliest archival records indicate the presence of a book trade on Notre Dame cathedral’s square at the beginning of the thirteenth century.7 Notre Dame was then surrounded by episcopal schools that needed books for their students and masters. No doubt, the presence in this area of the royal residence and of wealthy aristocrats, both lay and ecclesiastical, also provided some patrons for artisans able to produce richly ornate manuscripts (Plate 46.1). Nevertheless, the long-established ecclesiastical use of books, the clerical status of students and masters in schools, the Church’s claim to censorship of ideas and knowledge, and the high symbolic value of medieval script associated books with the Church. It is, therefore, not surprising to see the book trade concentrating both in Paris and in London around the cathedral. Since more precious manuscripts have been better preserved than the quickly written, more utilitarian, undecorated, school manuscripts, it is impossible to measure the relative weight of each category. But the absence of book craftsmen on the Right Bank, a part of the city where princes and high nobles had their Parisian residences, tends to indicate that the location of schools and the proximity of the cathedral played the main role in the settlement of the book trade. When schools multiplied and expanded on the Left Bank, book craftsmen followed: In the mid-thirteenth century there were parchmenters, illuminators, and booksellers under the dominium of the abbey Sainte-Geneviève, where new schools were established outside of the bishop’s authority. Rapidly the Left Bank became the stronghold of the “University” with its colleges, nations, masters’ houses, and students’ residences.

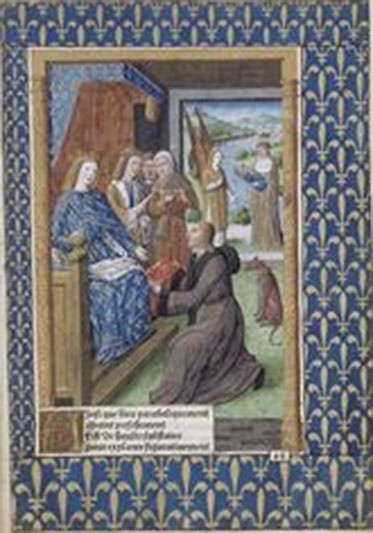

Plate 46.1 Woodcut featuring the Parisian bookseller and printer Antoine Vérard presenting to King Charles VIII of France Jardin de plaisance et fleur de rhétorique, by the French poet François Villon, Paris. Public Domain (BnF, Gallica scans.). Vérard had a shop on Notre-Dame Bridge and another one at the Palais in 1485. Several of his prints represent him offering a book to a patron.

Two streets in particular accommodated Parisian book artisans. Most of the late thirteenth-century inhabitants of the rue des Écrivains were parchmenters, a situation that persisted and that explains why that street changed name around 1400 to become rue de la Parcheminerie or rue des Parcheminiers (“Parchmenters Street”). Crossing it was the rue Érembourg-de-Brie, where the vast majority of Parisian illuminators were established, along with most of the bookbinders. Both illuminators and bookbinders dominated the number of taxpayers on this street to the extent that we could see it as a book production street. Booksellers, on the other hand, present a very different pattern of settlement. Half of those identified in late thirteenth-century Paris were established in several parts of the Left Bank, beside convents or colleges, sometimes accompanied by one other trade. The others concentrated in the Cité, on the street starting at Notre Dame’s cathedral (rue Neuve-Notre-Dame), which they shared with a few illuminators, bookbinders, and parchmenters, but also with many seal makers and poultrymen. Fiscal documents become silent after the tax exemption of all book craftsmen in 1307, but archival material suggests that the two former main areas of the book trade (the Left Bank and the Cité) remained the same during the fourteenth century and that isolated booksellers were scattered on the Left Bank.

At the turn of the fifteenth century, traces of book trade activities appeared on the Right Bank, in the main Parisian cemetery. What little information we have on that trade suggests the sale of small, inexpensive used books rather than the production of manuscripts. During that century, book artisans settled in new parts of the capital. On the Left Bank a new street (rue Saint-Jacques) developed into a concentrated zone of booksellers. It became after 1470 the street of printers and publishers, and around 1550 the main artery for the book trade.8 In the Cité, the Palace (Palais), a former royal residence now hosting the crown’s courts of justice and the chancery, attracted booksellers specializing in legal books for the many jurists using the various tribunals in the area. The Palace was in the sixteenth century one of the most active centers for the Parisian book trade. Finally, book artisans had shops on the bridges linking the Cité to the Left Bank, and especially on Notre-Dame Bridge connecting the Cité to the Right Bank. Illuminators and bookbinders had established themselves on the bridge since 1421, followed by booksellers, along with professional writers specializing in the writing of books (écrivains de lettres de formes) rather than of charters or letters. As clients diversified and multiplied, the book trade adapted, and this fact explains the expansion outside the traditional areas of concentration of the trade near the schools and the episcopal quarter. But the settlement of book artisans within the same areas of the city suggests their close ties, a fact confirmed not only by professional links but also by many social and family relationships.

In London, as in Paris, book craftsmen were concentrated in certain parishes, more specifically on the north, northwest, and east sides of St. Paul’s Cathedral. Their physical proximity fostered personal ties between neighboring book artisans. In London, as in Paris, they married their children within the trade; they pledged for each other; they were last will executors for a deceased peer, etc. Above all, they belonged to the same fraternity under the authority of the booksellers (in Paris since 1401) or stationers (in London since 1403), who were therefore acknowledged as responsible for the whole trade and for every step in the production of a book. Such a responsibility provided these individuals with a prominent status among book artisans. When printing developed in Paris in the late fifteenth century it did so in the Left Bank, where booksellers had been established for two centuries. Moreover, it grew among booksellers, the only craftsmen socially and economically prominent enough to get involved in the new techniques.

Book Production under the Control of Booksellers

Parisian libraires distinguished themselves from other artisans involved in the making and selling of books. Not only were they geographically scattered, while other crafts were concentrated, but they also figured as masters of the whole trade either through their financial situation or through their dominant position in the fraternity.

In Paris, late thirteenth-century tax records clearly show the booksellers as the wealthiest of all book craftsmen, since 85% of them belonged to the medieval fiscal category of the gros, which meant they were taxed more than 5 sous parisis per year.9 Only 44% of the parchmenters or of the illuminators, and 28% of the bookbinders were in that category. Book craftsmen’s fiscal standing resembled that of modest and average merchants and artisans. Moreover, their distinctive fiscal position corresponds to the general picture of Parisian taxpayers: merchants were taxed substantially higher than artisans. Booksellers can be associated with merchants, whereas illuminators, bookbinders, parchmenters (or later paper makers), and scribes were artisans producing the material and realizing the various steps of the making of a book. Even when a bookseller mastered one or several of the artisanal skills necessary for producing a book (as is obvious when some artisans became libraires, or when individuals were designated alternatively as bookseller and illuminator, scribe, or bookbinder), the term libraire (or stationaire) implied more than merely selling books.

The commercial activities of booksellers meant they had to understand, to foresee, and to answer the needs of their clients. Such functions explain their scattered settlement near schools or palaces, or later even the cemetery. A bookseller like Marguerite de Sens, a member of a family of university stationarii established between c.1270 and c.1340 on Saint-Jacques street next to the convent of the Dominicans in Paris, could supply the bookish Mendicants with the volumes they required for their studies and work.10 In the early fifteenth century, Petrus de Verona, a former Parisian university master, was selling very expensive books to rich customers in the royal entourage, proposing manuscripts to English ambassadors in Paris, receiving them in his house on Saint-Jacques street to show them his stock, selling two books to the Prince Louis of Orléans for c.£340 and providing the library of the abbey Saint-Victor with 12 books in a single year (1422–3).11 Records, however, never use the term “libraire” to qualify Petrus de Verona’s activity. The same is true for all kinds of people who knew of bibliophile aristocrats. By the late Middle Ages, authors, secretaries, or prominent merchants like the Italian brothers Rapondi could offer their services to enrich expanding princely libraries.12 The book trade of the fifteenth century was animated by a greater variety of actors than thirteenth-century clergy and university members. Yet production of new manuscripts remained over the centuries the prerogative of qualified booksellers.

Since most late-thirteenth century booksellers (librarii) were also stationarii holding university exemplaria and peciae for scribes to copy, their involvement in the production of new manuscripts is beyond doubt. For centuries to come, Parisian booksellers would act as entrepreneurs and coordinators of book production and trade. These functions explain why some thirteenth- and fourteenth-century bookbinders and illuminators were established near booksellers, even outside of their concentration areas. In those cases, the merchant (libraire) controlled the making of manuscripts for his clients, while providing work to artisans in his neighborhood. Some well-documented cases show booksellers having copies made at the request of a patron. Such was the case of André le Musnier, designated as illuminator (1443) established on Notre-Dame Bridge, by the cathedral, son of Guyot le Musnier, an illuminator and bookseller, brother-in-law to another illuminator.13 In 1450, André was called libraire, while in 1458 he was registered as bookbinder in a college account, before he became one the four main booksellers of the university (1461), which vainly attempted on two occasions to exclude him from its ranks for disobedience (1467 and 1474). André had apprentice illuminators, worked in close cooperation with other illuminators, and had a scribe outside of Paris whom he supplied with work and material to write quires of manuscripts. When he died in 1475, his widow inherited their house and remarried twice to booksellers, presumably pursuing the activities of her first husband. Such booksellers had existed in Paris for many decades. Another example was Thévenin Langevin (1368–98), known as a university bookseller and scribe (écrivain), who received money from Louis, duke of Orléans, in order “to pay the scribes, illuminators and other craftsmen to make for milord of Orléans the book entitled Mirouer historial.”14 These men were wealthy enough to bear the cost of making new books, they were intermediaries between artisans and patrons, and they had responsibilities toward and privileges from the university. In other words they were the official masters of the trade and of the various crafts involved in the making of books. When paper makers appeared in the late fourteenth century, or when printers multiplied after 1470 (Plate 46.2), they did not alter the socio-professional organization set in place for decades, leaving the bookseller as the entrepreneur in charge of coordinating the printing and decoration of books. In medieval Paris being a libraire meant, as it still does, selling books, but it especially meant being able to provide used and newly made books, and having them made by others as the need arose.

Plate 46.2 Dedication miniature showing the bookseller Antoine Vérard giving his book to Anne de Bretagne. Illumination on parchment from Le trésor de l’âme by Robert de Saint-Martin, c. 1491–1500. Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Vélins 350, fol. 6r.

The patterns of the Parisian book trade were not unique. In Barcelona, for example, research in notarial contracts indicates that professionals of the fourteenth- and fifteenth-century book trade were closely linked, their activities complementary, and that the libraterius was the one coordinating the production of books. Exercised mainly by Jewish or converted craftsmen, the arte librarie was transmitted within families, giving birth to dynasties of libraterii who trained apprentices, sold paper and other writing materials, bound books, appraised manuscripts, imported and exported them, and had them written and decorated. They were also gathered in a fraternity under the protection of the Holy Trinity. In Barcelona, booksellers contracted into temporary associations for a specific production and shared profits. Such society contracts integrated printers when they first settled in Barcelona in the late fifteenth century: the printer contributed his work and material, while the libraterius provided the necessary capital. In Barcelona, as in Paris, booksellers were clearly acting as entrepreneurs in the making of both manuscripts and printed books.

In England, communities of book craftsmen grew first in university towns, Oxford and then Cambridge, and in London around St. Paul’s Cathedral in the late twelfth century. Other urban centers such as Lincoln, Norwich, and York also witnessed the establishment of different types of medieval book artisans, including scribes, illuminators, and parchment makers. The cultural needs and intellectual life of these centers determined the size of the communities, which were usually located in specific quarters or streets, as in Paris. In Oxford, book artisans worked in Catte Street, while in London late medieval records point to Paternoster Row as the street concentrating makers and sellers of books near the cathedral. By 1403, London had a fraternity of “writers of text-letters, limners, and others who bind and sell books” under the authority of two wardens, one illuminator, and one text writer. After being designated by several names (Limners and Textwriters, Limners and Stationers) the fraternity became the Stationers’ Company in 1441. The London stationer occupied the same position as the Parisian libraire, dominating the other book crafts and coordinating their work in the making of books, while mastering one or more of these crafts.

In Bologna, book artisans were early on under the control of the university which in 1317 required an oath from omnes scriptores, miniatores, correctores et minorum repositores atque rasores librorum, ligatores, cartularii et qui vivunt per universitatem et scolares. Craftsmen not involved with university members did not have to swear the university oath, but stationers and their shops were still subjected to town authority. San Geminiano parish had a concentration of book artisans in the late thirteenth century; the stationarius was a scribe or a coordinator of written works.

The emphasis placed here on professional book makers and sellers certainly does not reflect all cases of book production and circulation. Lack of documentation makes it difficult to identify all the occasional actors of the medieval book trade, but they should not be dismissed, for they animated the book trade for centuries. Various princes were active patrons, keeping copyists and illuminators among their retainers, ordering the making of specific books, or accepting lavish copies authors gave them in exchange for a stipend (Plate 46.2). Students copied books to support their studies. Monks copied for monastic libraries. Books were precious goods because of their high cost and their symbolic function. They were, therefore, transmitted from one generation to the next and used as bequests, gifts, pawns, or guarantees. They attracted thieves and crossed centuries. By the late Middle Ages, specialized craftsmen had multiplied all over Europe to answer a growing need for more varied books well before the appearance of printing. In important cultural centers like Paris the book trade extended after 1350 beyond its original university sphere of influence but always under the dominant figure of the bookseller.