Chapter 48

The Lindisfarne Scriptorium

The monastery of Lindisfarne on Holy Island in the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Northumbria (northeast England) has long been thought to have possessed an important Insular scriptorium during the seventh and eighth centuries. Along with Canterbury and Wearmouth-Jarrow it has been considered one of the few early English centers that can be shown to have made books that still survive. Central to this premise is one of the greatest of early medieval manuscripts—the Lindisfarne Gospels (London, BL, Cotton MS Nero D.iv), which was thought to have been made at Lindisfarne to mark the translation of the relics of St. Cuthbert to its high altar in 698, but which has recently been re-evaluated and dated to c.715–20. And yet David Dumville (1999–2007, 1) has felt able to suggest that there was never any such scriptorium. In order to understand such divergence it is useful to review the historiography.

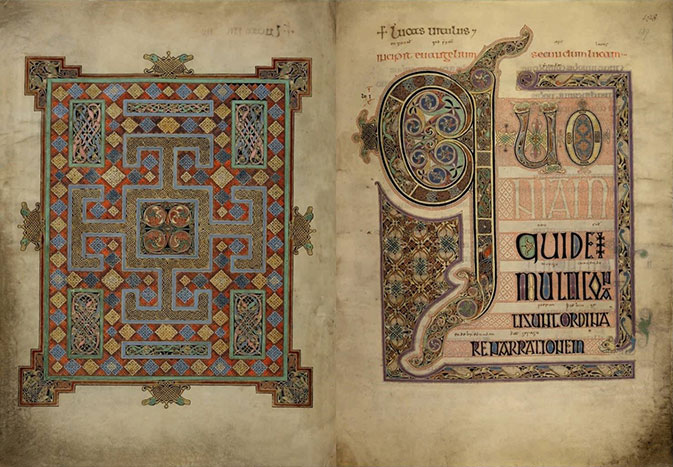

In the hefty commentary accompanying the first full facsimile of the Lindisfarne Gospels (see Plate 48.1), published in 1956–60,1 Julian (T. J.) Brown discussed the palaeography of the manuscript in full for the first time. Brown was a classicist by training (specializing in Greek vase painting, inter alia) and, as a young curator in the Department of Manuscripts in the then British Museum Library, was allocated to the project and so began his palaeographical career. Working closely with the archaeologist Rupert Bruce Mitford of the Department of Medieval and Later Antiquities in the British Museum and involved in excavating Sutton Hoo, he closely analyzed the relationship between the script and decoration. They determined that the scripts were the work of one hand and that this hand, as stated in the colophon added by the monk Aldred in the mid-tenth century, was that of Bishop Eadfrith of Lindisfarne (698–721). They could not conceive of a busy bishop making time for such work and thus concluded that he must have undertaken it before assuming office in 698 and that it was intended to celebrate the translation of the relics of St. Cuthbert (died 687) to the high altar of Lindisfarne that same year. They also examined the relationship of the manuscript to two stylistically related volumes—the Durham Gospels (Durham, Cathedral Library, MS A.ii.17) and the Echternach Gospels (Paris, BnF, MS lat. 9389) and concluded that these manuscripts were by the same hand, which they termed the “Durham-Echternach Calligrapher.” In order to get round the chronological issues raised by dating the Lindisfarne Gospels as early as 698, which sat uneasily with the broader sequencing of extant Insular manuscripts and the relative stylistic sequencing of the three books in question, they suggested that Eadfrith was a pupil of the Durham-Echternach Calligrapher, but that the latter actually undertook his work on Durham and Echternach after Eadfrith produced Lindisfarne.

Plate 48.1 Lindisfarne Gospels (London, BL, Cotton MS Nero D.iv), fols. 138v–139r, Luke Cross-Carpet Page and Incipit Page.

Brown argued that (Phase I) Insular attempts to produce a settled, indigenous rediscovered version of Half-uncial script resulted in what he termed a “reformed Phase II Insular half-uncial.” This was a heavy, straight-pen script characterized by breadth and rotundity of aspect, by a strict adherence to head and baselines (reinforced by the extension of headstrokes linking words, despite the excellent standards of word separation—a contribution to legibility which he attributed to Insular scribes) and by the inclusion of Uncial lemmata, especially at line ends. He attributed this development to Eadfrith, who in turn influenced the hand of his master in the Durham Gospels. The Echternach Gospels, written in a slightly less formal version of the script, with a slanted pen and with the inclusion of more minuscule letterforms and ligatures, were presented as something of a rushed job by the same hand, writing a “set minuscule,” perhaps under pressure to produce a gift for Willibrord’s new “Northumbrian” foundation of Echternach (Luxembourg).

Incorporating this thinking into his wider narrative of the development of an Insular system of scripts, Brown, in his as yet unpublished Lyell Lectures and a number of important articles,2 therefore presented the Lindisfarne Gospels as the fulcrum of an axiomatic shift in Insular palaeography, stabilizing the developments of Phase I which had been led initially by Irish scribes, indebted to selective late Antique influence but free from more recent Roman intervention and working in comparative isolation from wider Continental developments. Irish influence in Northumbria, coupled with more contemporary Roman Uncial, as written in Gregory the Great’s time (died 604), transmitted via the Romanizing Northumbrian twin monastery of Wearmouth-Jarrow. These were perceived by Brown to have resulted in the Phase II shift, in which Ireland subsequently partook whilst also perpetuating its Phase I traditions. Brown also perceived a close stylistic relationship between the scripts of the Lindisfarne Gospels and the Book of Kells, which made it difficult for him to accept that the latter could be a product of Iona or Ireland, c. 800. He accordingly suggested that Kells might be earlier in date (perhaps mid-eighth century) and made in an unknown Scottish monastery—a suggestion met with considerable scholarly derision.3

In 1980 Brown’s student, Christopher Verey, contributed to the commentary to the Early English Manuscripts in Facsimile volume on the Durham Gospels and identified a common, near contemporary correcting hand at work here and in the Lindisfarne Gospels.4 This reinforced the connection between the two volumes and was presented as the work of a Lindisfarne scribe. Verey, here and in subsequent articles,5 also explored the textual relationship between these three and other related manuscripts, and strengthened the concept of an influential Lindisfarne scriptorium, active around 700.

Insular Half-uncial was of E. A. Lowe’s “majuscule” category, but what of contemporary “minuscule”? Brown saw enough of a relationship between the minuscule “lapses” of the Durham Gospels and the set minuscule script of the Echternach Gospels to suggest that they were the products of the same tradition. He related this minuscule to that of the Vatican Paulinus (Vatican City, BAV, Pal. lat. 235), which he and Tom McKay saw as representative of the Lindisfarne scriptorium’s more usual minuscule “library” book production.6 In 1987, as part of the proceedings of a conference in Durham to mark the anniversary of St. Cuthbert’s death, Michelle P. Brown, another of Brown’s students, summarized the thinking to date on the Lindisfarne scriptorium.7

The monolithic construct of a Lindisfarne scriptorium, built on the substantial foundations of the Codex Lindisfarnensis facsimile study, remained relatively intact until a series of articles by Dáibhí Ó Cróinín launched an attack on the underlying historical assumptions and, in particular, on the place of the Echternach Gospels and related manuscripts within the edifice.8 He challenged the assumption that Echternach was essentially an English foundation simply because St. Willibrord and his sponsor, Bishop Egbert, were themselves Northumbrian and pointed out that they had been based in Ireland at a monastery named Rath Melsigi (perhaps in Co. Carlow?) prior to launching the mission, which was, therefore, essentially an Irish endeavor. Through his study of the Augsburg Gospels, Ó Cróinín pointed to shared Irish palaeographical features in this and the Echternach Gospels, and to work undertaken in the eighth-century Echternach scriptorium by the Irish scribes Virgilius and Laurentius. In this work, and in subsequent publications by William O’Sullivan,9 former Keeper of Manuscripts at Trinity College Library, Dublin, criticism was directed at what was presented as an overly pro-English view of the origins and development of Insular (specifically so-called “Hiberno-Saxon”) book production. Nancy Netzer, in the Durham St. Cuthbert conference proceedings and in her subsequent monograph on the Trier Gospels from early eighth-century Echternach (Netzer 1989 and 1994), slowed the nationalistic trajectory of the pendulum of debate to a more workable level, analyzing the Echternach scriptorium and presenting it as an Irish-Northumbrian collaborative endeavor which rapidly absorbed more local influences from Merovingian Gaul to form its own distinctive style. The Echternach Gospels were perceived as an early product of this scriptorium, after the foundation of Echternach in 689.

In 1993 a selection of Julian Brown’s collected papers was published as a tribute by his colleagues.10 This stimulated a review in 1999 by David Dumville, in what was essentially an overview of the state of play regarding the study of Insular palaeography.11 While allegedly debunking the idea of a Lindisfarne scriptorium in the course of this, Dumville suggested that Wearmouth-Jarrow was actually responsible for the Phase II reform of the Insular system and that—as its distinctive Phase II minuscule seems to have evolved as part of a publishing campaign, identified by Malcolm Parkes,12 to circulate the works of Bede in the mid-eighth century—the reform of Insular Half-uncial is likely to have occurred there. Such developments are, he would suggest, unlikely to have been protracted.

How then is one to account for the time lapse between the Wearmouth-Jarrow scriptorium’s reform of high-grade book script by the introduction of Italianate Uncial around 700 and its completion of the process by a reform of Half-uncial and minuscule around 740–60? I have suggested that it remains equally likely that the Wearmouth-Jarrow campaign of book production employing minuscule script for literary works, commentaries, and the like, rather than the distinctive Romanizing Uncial which it reserved for sacred texts, was itself influenced by the earlier tradition of cursive minuscule scripts. These are found in an Insular milieu from areas as diverse as seventh- to eighth-century Ireland, Continental mission centers such as Willibrord’s Echternach and Columbanus’s St. Gall, the Canterbury school of Theodore and Hadrian, and Boniface’s southwestern England and the Frisian mission field, and are also to be seen as part of the evolution of the genre into what has been termed Phase II. Did Wearmouth-Jarrow need Half-uncial when it had its own Uncial for higher purposes and minuscule for others? If it did, there are—as we shall see—better candidates as examples of what this may have looked like, rather than the Lindisfarne Gospels, which displays little affinity with its codicological and artistic traditions.

A major concern, in the course of these debates, was that the authors of the Codex Lindisfarnensis commentary, and Brown in his subsequent work, had not taken due account of developments in historical research which were demonstrating that Ireland was not as isolated from the late Roman and post-Roman world as had been thought and that the early Insular scripts had not evolved completely separately. A closer reading of Brown, especially his articles on the debt owed by Insular book producers to late antique palaeography and codicology (T. J. Brown 1993, 125–40 and 221–44), shows that this was largely unjustified, but the commentary volume (Kendrick et al. 1956–60) certainly failed to take account of the nuanced historical context, a problem enhanced by its adherence to an absolute terminus ante quem for the Lindisfarne Gospels of 698.

In 2001 Richard Gameson13 published an article questioning, as had the aforementioned commentators, whether Aldred’s colophon (added in the 950s–960s, after the community had relocated from Lindisfarne to Chester-le-Street) could be taken at face value. It certainly cannot, for Aldred had his own agendas, but the Codex Lindisfarnensis commentary authors had not relied solely on this in their acceptance of a Lindisfarne origin and early dating. Larry Nees (2003) followed with an article questioning the late seventh-century dating, suggesting that a date later in the eighth century would sit more comfortably within the art historical sequencing of Insular manuscripts.14 At this time a further facsimile (this time in color and a more accurate version from digital photographs, of exact dimensions and carefully color-balanced) and commentary on the Lindisfarne Gospels, authored by myself, was already in press.15

In this and a subsequent work,16 I ascribed the Lindisfarne Gospels a terminus post quem of 715, on the grounds of its inclusions of lections being introduced in Rome at that time as part of the Good Friday liturgy and of its probable place in the development of the Cuthbertine cult. The translation of the relics of St. Cuthbert to the Lindisfarne high altar in 698 was not the sort of preplanned event that a complex book like this would have been made for, and the shaping of the cult to fit an eirenic agenda of reconciliation was undertaken by Bishop Eadfrith, with the assistance of Bede, whom he commissioned to rewrite St. Cuthbert’s vita during the second decade of the eighth century. From around 710 Ripon was also establishing a cult of St. Wilfrid with a book as its focus—a purple codex with chrysography, redolent of Mediterranean culture. This may have inspired the production of a similarly impressive cult book in honor of St. Cuthbert, but one that conflated a wide range of cultural influences and signifiers that stretched from Ireland to the Near East. It is essentially the work of one gifted artist-scribe, which says something about the eremitic spirituality of the place in which it was made, which points to a Columban house, for Columba and his colleague Canice won renown as hero-scribes, writing books singlehandedly. It would probably have taken at least five years for one person to produce, alongside other duties. If its artist-scribe was indeed Bishop Eadfrith, his death in 721 provides a terminus ante quem, although work was completed after this hand was out of the picture.

Even if the Durham and Echternach Gospels were not, in fact, by the same hand, which seems likely, they are from a common script background. Lapses at line ends in the Durham Gospels, and to a lesser extent in Lindisfarne, indicate that their scribes were familiar with the sort of cursive and set minuscule scripts that are given fuller rein in the Echternach Gospels. This need be interpreted as no more than the sharing of a common tradition that embraced parts of Ireland, Scotland, Northumbria, and the Continental mission fields at the time. The Vatican Paulinus may have been made at Lindisfarne, and is certainly how we can imagine one of its schoolbooks would have looked, but it need not necessarily have been.

To my mind the development of Insular Half-uncial was a gradual process, evolving in the Columban parochia toward a more formal, regular type throughout the seventh century. This script had achieved maturity by the time that the Durham Gospels were written, probably a generation or more prior to the Lindisfarne Gospels,17 the latter representing a precocious pinnacle within the development of Phase II Half-uncial, rather than its genesis.18

The Durham Gospels are somewhat closer to the Columban tradition and exhibit little of the Wearmouth-Jarrow influence apparent in the Lindisfarne Gospels. The same applies to text. The Durham and Lindisfarne Gospels seem to have been in the same center shortly after their production, as the same hand corrects both.19 His work in Durham formed two campaigns, an initial correction and a later one made with reference to the Lindisfarne Gospels or its exemplar (probably the Lindisfarne Gospels itself, as there appear to be a few corrections by the hand of the Durham-Echternach Calligrapher therein). Durham may have been made in another scriptorium of similar Columban background, such as Melrose, and subsequently joined the Lindisfarne Gospels or, given their similarities, may represent an earlier phase of production at Lindisfarne. In my view, the Echternach Gospels also belong to this earlier generation and were probably written in Echternach, the scriptorium of which was manned by scribes of various origins, trained in the Irish tradition

It therefore seems likely that by c.710 there was at least one highly accomplished artist-scribe, probably the head of the community, working at Lindisfarne on its great cult book as a focus of pilgrimage. He was highly creative and technically innovative (inventing the lead pencil and the light box and producing a wide-ranging palette using, as demonstrated by Raman laser analysis, only six locally available mineral and vegetable extracts, handled with the flair of an experimental chemist). He was versed in diverse liturgies, had obtained a Neapolitan textual exemplar via Wearmouth-Jarrow that makes the Lindisfarne Gospels, along with the Ceolfrith Bibles, the most authentic medieval representatives of St Jerome’s Vulgate Latin translation, and constructed complex images in which the iconic and aniconic were merged in statements of ecumenical orthodox churchmanship, exegetical insight, and social inclusion. He wrote a well-developed Half-uncial and set minuscule indebted to the Columban tradition from which the monastery sprang and occasionally lapsed into a cursive minuscule indicative of lower-grade book production, such as that embodied in the Vatican Paulinus. The Lindisfarne Gospels were a semi-eremitic endeavor of opus Dei conducted by one person, but at least one other hand was present locally and supplied the Eusebian apparatus to complete the work, possibly after Eadfrith’s death in 721. A further hand corrected it and the Durham Gospels, with reference to one another. Whether there was a formal scriptorium, in the manner of more cenobitic monasteries such as Wearmouth-Jarrow, or whether the monks of Holy Island worked separately, it is likely that books were made there and that they merged a Columban background with more recent “Romanizing” influences via Wearmouth-Jarrow and Kent and Near-Eastern elements, to form a distinctive, quintessentially “Insular” style.

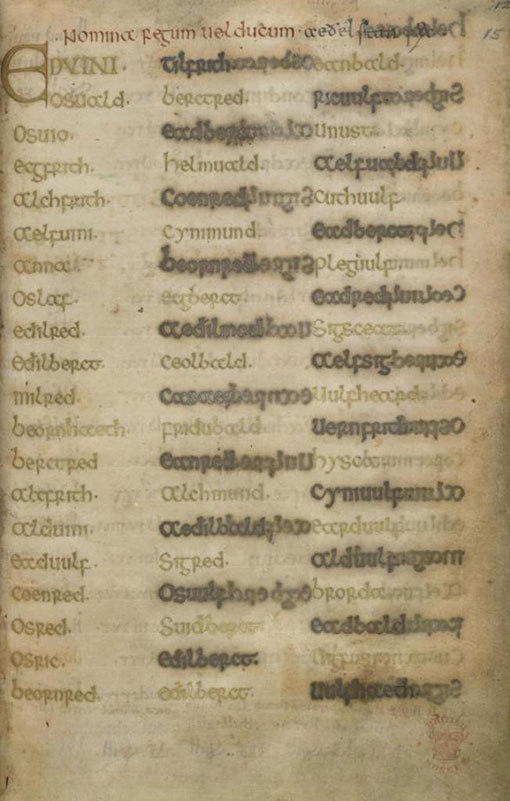

The script and artwork of the Lindisfarne Gospels went on to exert an influence throughout the eighth century in works such as the Chad Gospels (Lichfield Cathedral, MS 1), the Cambridge-London Gospels (Cambridge, Corpus Christi College, MS 197B and London, BL, Cotton MS Otho C.v), the McRegul Gospels (Oxford, Bodleian Library, Auct.D.2.19), and the Book of Kells (Dublin, Trinity College, MS 58). A later example of Lindisfarne’s Half-uncial may be the Durham Liber Vitae (London, BL, Cotton MS Domitian A.vii; see Plate 48.2),20 which was probably the community’s benefactors’ book made soon after 840 either on Holy Island or at its daughter house of Norham-on-Tweed, where the community moved to temporarily in the face of Viking raids.

Plate 48.2 The Durham Liber Vitae (London, British Library, MS Cotton Domitian A VII, f. 7v), Lindisfarne or Norham-on-Tweed, 840s onward (the gold and silver script is the earliest).