Chapter 60

Text and Gloss

Despite their variety, ingenuity, and versatile use, glosses generally remain subordinate to the text they comment upon. The text is the inspiration; the gloss is the explanation. The text provides the idea; the gloss documents the idea’s intellectual afterlife. The text weaves together meaning; the gloss teases it apart. When written as interlinear and marginal notes, the glosses show their dependency on the text both through what they say and by where they are located, and even the more independent variety of glossing, the continuous or chain commentary, is still inspired by an original composition which provides a precise point of departure and an inherent principle of organization. Often the glosses are more than a simple reflection on the grammatical, literary, or doctrinal reality of the text they explicate; they frequently bring more detail to the original composition, reinforce its message, and broaden its appeal. Even when they argue against the text, the glosses nevertheless enrich the understanding of the work’s readership. The most extreme case and a complete reversal of roles is seen on rare occasions where the text makes little, if any sense at all without the accompanying notes. Here, the glosses have become an integral part of the process of creation, not just a scholarly afterthought.

The basic relationship between text and gloss was well understood during the Middle Ages, as is seen in Huguccio’s popular etymological dictionary Derivationes, written sometime in the later twelfth century.1 Huguccio says that one needs to distinguish between comment, gloss, translation, and text. A comment does not consider the joining of words but their sense (verborum iuncturam non considerans, sed sensum), whereas a gloss provides a clarification of the meaning of individual phrases and even words (non solum sententiam sed etiam verba attendit). The text, in contrast, is the book of the author without any further explanatory notes (textus est liber…sine littere vel sententie expositione).2

Thus, it is clear that clarifying grammar, explaining the meaning of words, and unlocking the deeper significance of the text are the main concerns of glossing, at least until the gloss transforms itself to become a textual construct in its own right and thus inspires its own glossing. The continuous catena commentaries organized by lemmata as textual cues are the best examples of this gloss metamorphosis. The different levels of gloss sophistication can be and often are brought into play simultaneously, even though frequently the process of glossing seems to be shaped by the intellectual needs of a particular readership. Especially when texts were used for teaching, the complexity of their annotations would reflect the educational stage at which these texts were incorporated into the curriculum. In some medieval textbooks we might even find multiple layers of glosses introduced independently of each other by various users of the book over an extended period of time. In such cases the glosses are seen to be in dialogue not only with the text proper but also with the other layers of annotation. Even when they result from private reading and study, the individual glosses vary in difficulty and purpose, reflecting the scholarly proclivities of the person who wrote them.

This chapter explores the complex intellectual interplay between text and gloss, using examples from the vast but lesser known field of Latin biblical versification from the later Middle Ages.3 The poems of Peter Riga (d. 1209), Leonius of Paris (d. c.1201), Alexander of Ashby (d. 1208 or 1214), and William de Montibus (d. 1213),4 as well as some anonymous compositions, such as the Liber Generationis Iesu Christi (late eleventh century), the Liber Prefigurationum Christi et Ecclesiae (late eleventh century–early twelfth century), and the Capitula euangeliorum (late thirteenth–early fourteenth century)5 will be mined for representative and instructive occurrences of text and gloss interaction which will demonstrate the various approaches the glossators employed in their work. And finally, it has to be remembered that apart from interacting with the text itself, the glosses are also an intermediary between text and reader. Sometimes they may even require a very active involvement from the reader, especially when the position of the glosses is ambiguous and their textual anchors (or lemmata) difficult to establish. In any case, the centrality of the glosses to the understanding of the text’s message is undeniable not only for medieval students, masters, and scholars but also for their modern counterparts.

Interlinear Glosses: Clarifying the Meaning of the Word

On this first level the role of the glosses was to provide help with the basic understanding of how the text was constructed. Avoiding confusion and explaining uncertainties must have been the guiding principles of the glossator at this stage. It was of primary importance to make sure that the reader, who probably was a beginner Latin student, grasped the literal meaning of the text, from where he could then move to uncovering its deeper significance. Thus, it is evident that this first level of glossing is closely related to teaching and is generally meant for younger or less advanced students.

The interlinear glosses can be non-verbal, i.e., construe signs, accentual marks, numerals (Roman and later also Arabic), small letters, and other symbols, as well as verbal, explaining various introductory but essential aspects of the text. In the field of prosody the glosses usually deal with issues of accents, meter, and poetic techniques. The problems of grammar, both morphological and syntactical, are exemplified by supplying omitted prepositions, explaining cases, clarifying subjects and objects, especially when they are expressed by pronouns, and providing help with word order and clause subordination. In the matters of vocabulary the glossators normally offer synonyms (rarely antonyms), give Latin equivalents for Greek words or vernacular translations for Latin ones, and supply names that both aid and enrich the reader’s understanding. Because of their highly localized nature, these types of glosses are commonly placed between the lines and in close proximity to their lemmata but because of special limitations they can be displaced, sometimes even as far as the margins. In such cases, the critical judgment of the reader is required in order to connect them to their intended place in the text. Despite these occasional difficulties, interlinear glosses are generally short, clear, and unambiguous. Their illuminating quality and educational value are unmistakable.

The examples of medieval interlinear glosses are innumerable and ubiquitous. They are found in manuscripts throughout the Middle Ages and in a variety of languages, even though Latin is best represented. Here only an illustrative selection will be included. For instance, in the Liber Generationis Iesu Christi we see the following concise treatment in the story of Ruth coming to Boaz’s bed in the middle of the night in order to convince him to marry her (see Ruth 3:7–13):6

The glosses to these four Leonine hexameters are all useful for a number of reasons. First, they help with simply grasping the meaning of the poem by identifying the protagonist of the story Boaz (“uir” = “Booz”), by providing the morphological gloss “per legem” for the less obvious ablative of manner “lege” (“by law”), and by explaining the adverbs “prius” and “secundo” with the more easily understood, especially for “secundo,” “in prima uice” and “secunda uice” (“at first…but then…”). In addition, the glosses simplify the poetic language of the verse by annotating poetic expressions such as “uenerat hora thori” (“the hour for going to bed had come”), “tangit uerbis” (“she touched him with her words”) and “tactibus angit” (“and ensnared him with her caresses”) with the more prosaic “i.e. nox ut iret dormitum” (“that is, the night, so that he might go to sleep”), “alloquitur eum” (“she spoke to him”) and “et tangit” (“and she touched him”). The rest of the glosses provide useful synonyms, i.e., “sopori” = “somno,” “recreare” = “suscitare,” “propinqui” = “cognati,” and “excusat” = “renuit.” All in all, in this passage the explanations of the glossator are manifestly aimed at helping the reader’s understanding of the Latin and at elucidating the basic meaning of the poetic text.

Another type of interlinear gloss is seen when non-verbal marks (i.e., dots in various configurations, superscript letters, or Roman numerals) are placed above or more rarely below the words in order to help the reader construe the correct meaning of the sentence. Such annotating is necessary because of the well-known fact that the demands of metrical versification often lead to a transformation of the customary ways of expression found in prose texts. An example of this glossing technique is seen in the early twelfth-century poem the Liber Prefigurationum Christi et Ecclesiae, vv. 233–4, where the mystery of the Eucharist is explained as follows:7

Verse 233, containing four potentially confusing accusatives, must have been considered especially difficult. Thus, superscript lettrine were added telling the reader how to rearrange the words following the alphabetical order of the letters. As a result, the sentence has to be construed as follows: “Aisti esse tuum corpus benedictum panem” (“You said that your body was the holy bread”). By providing this help the glossator is making sure that “corpus” is linked with “tuum” and “panem” with “benedictum,” and not vice versa. The point of this annotation contains doctrinal significance as well as grammatical import.

One extreme case, in which the text of the poem makes little sense without its glosses, is found in the mnemonic composition Capitula Euangeliorum, which dedicates one verse to each chapter of the four Gospels. Because of this excessive brevity, the text of this work makes no grammatical sense whatsoever; rather, each line of the poem represents a string of unconnected words that are lifted directly out of their biblical context without any attempt to connect them into a coherent sentence. Thus, the glosses added to the poem are extremely useful. They not only help the readers understand better the cryptic text in front of them, but also provide clues to identifying the precise biblical verse to which the poet refers. A short example from the beginning of the Gospel of Matthew will suffice here:8

At a first glance it is not easy to grasp the meaning of these verses. However, it quickly becomes apparent that each of the words that constitute this mnemonic composition represents a verse or rarely a section from the first four chapters of the Gospel of Matthew. For example, the biblical references for the last poetic line are: desertum] Mt 4:1; Zabulon] Mt 4:15; piscatores] Mt 4:18; sanitates] Mt 4:24. The glosses are really helpful here since they explain that “desertum” refers to Christ being tempted in the desert (temptatus in deserto), while “piscatores” (“fishermen”) brings to mind the encounter between Jesus and the future Apostles Simon (Peter) and his brother Andrew (uocat apostolos). Also, “Zabulon” is glossed with “terra” (“the land of Zebulun”), which tells the reader both that “Zabulon” has to be understood as a genitive and that the poet is indeed taking this particular mnemonic cue from Matthew 4:15, where we see the expression “terra Zabulon,” and not from Matthew 4:13, where the biblical text reads “in finibus Zabulon.” Finally, the gloss “multorum” above “sanitates” is a general reminder of the multiple healing miracles performed by Jesus during his ministry in Galilee. All in all, the interlinear glosses to the anonymous Capitula Euangeliorum are indispensable facilitators in the understanding of a very fragmented and often cryptic text.

Marginal Glosses: Explaining the Organization and the Meaning of the Text

The simplest marginal glosses are short notes that assist the retrieval of information, provide a reference, or simply draw the reader’s attention to important elements in the narrative. A passage from the Book of Daniel included in Alexander of Ashby’s biblical versification Breuissima comprehensio historiarum, vv. 565–80, illustrates this annotating approach. The marginal glosses are indeed numerous and very useful for finding a specific biblical episode in the poetic account (i.e., “The first vision of Daniel,” “About the three boys in the furnace,” “About Susanna,” and so on), as well as for identifying the protagonists of the narrative (i.e., “Daniel,” “Ananias, Azarias, Misael,” “Susanna”) and even for indicating when the action is taking place (i.e., “At the time of Darius, king of the Medes”):9

| In sompnis regi quid uisa notaret ymago, Hic uidet et recitat et subit inde decus. | Prima uisio Danielis |

| Qui socii fuerant in penis et prece secum, Consociat Daniel tres in honore sibi. | Ananias, Azarias, Misael |

| Cum regis statue capud inclinare recusant, Vis in fornacem regia trudit eos. | Secunda uisio Danielis De tribus pueris in fornacio |

| Ignis parcit eis, hostes perimit, stupet inde Rex et laudandum predicat inde Deum. | |

| In sompnis arbor regi quid uisa minetur, Dicit ei Daniel, res ea dicta probat. | Tercia uisio Danielis |

| Quid manus in muro scripsit, scriptura quid illa Signaret regi, nouerat atque notat. | Mane, Techel, Phares Sexta uisio Danielis |

| Illi parcit, obest, tutum facit esse, leonum Rictus, consortum fraus, pietasque Dei. | Tempore Darii Medorum |

| Urget Susannam seniorum perfida lingua, Dampnat plebs, Daniel liberat arte noua. | De Susanna |

In addition to these types of notes, the outer margins can contain information on the sources used by the author. An interesting example is seen in the biblical poem Historie ueteris testamenti by Leonius of Paris, who includes himself, i.e. Autor, among the authorities he draws on in his work, i.e., Moses (i.e., the Bible) and Flavius Josephus for the material added to the biblical narrative. In both instances the marginal source glosses provide only general indications rather than useful text references. The passage below represents Leonius’s versification of Genesis 22:14–19:10

| Quodque piis oculis Deus hic uidisset utrumque, | Moses |

| Inde loco nomen “Dominus uidet” indidit illi. | |

| Tunc uelut in uitam certa de morte remissum | Iosephus |

| Natum amplexitur, nato pater oscula figit. | |

| Gaudia nec celant lacrime, uix pectore toto | Autor |

| Leticiam capit ipse suam pietasque paterna | |

| Plena redit. Mouet inde gradum puerosque reuisit | Moses |

| Tantarum ignaros rerum campoque relictos. |

Often, when every single word in the verse is commented upon, we find letters or variously shaped signs placed above the words in the body of the poetic text. These non-verbal cues, also called signes-de-renvoi, are then repeated in the margins, followed by the intended comment. In this case the superscript signs are not glosses per se; rather, they designate links to the real comments, which are written somewhere else on the page. The reader is supposed to look for the corresponding twin marks in the margins or sometimes between the lines and uncover for himself the point of the annotation. This technique is attested in William de Montibus’s Versarius, a rich collection of short epigrams on numerous topics organized alphabetically.11 The following piece, entitled Dedicatio ecclesie is from the section on the letter “D.” The text and glosses are transcribed here from London, BL, MS Add. 16164, fol. 26r. The title of the epigram is written in red ink in the left margin of the manuscript. The glosses appear both to the left and to the right of the text of the verses:

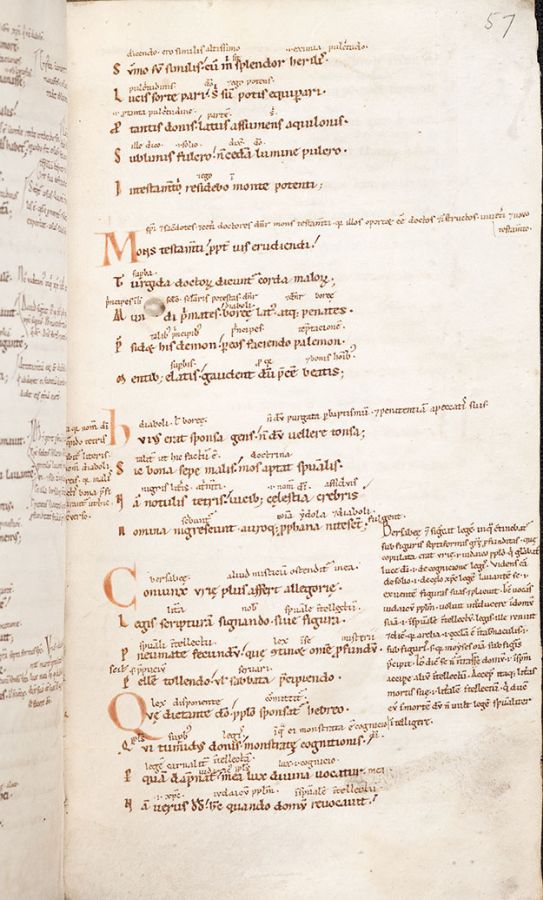

In the cases discussed above, the marginal glosses are still very short and relatively straightforward (i.e. sal means sapientia, scriptura stands for doctrina, and uinum denotes leticia spiritualis). With the exception of their location, many of these marginal notes are not very different from the interlinear glosses. In what follows, the tenor of the marginal glosses changes. They become complex comments on sense and doctrine either recording the thoughts of the medieval scholars studying the text or providing help to students at a higher level of education. Such marginal commentaries are found in countless medieval manuscripts. They are not restricted to subjects and disciplines but demonstrate universal applicability. Here the phenomenon will be illustrated by a short excerpt from the anonymous poem Liber Generationis Iesu Christi that outlines the allegorical meaning of 2 Kings 11 (Plate 60.1):12

Plate 60.1 © Heidelberg, Universitätsbibliothek, MS Salem IX 15, fol. 57r.

In addition to the interlinear glosses explaining that yet another mystical interpretation is to be uncovered in the figure of Uriah’s wife Bathsheba (aliud misticum ostenditur in ea), a long note is entered in the right margin close to the opening verse of the excerpt. It reads:

Bersabeae etiam significat legem, in qua continebatur sub figuris septiformis gratiae profunditas, quae copulata erat Vriae, .i. Iudaico populo, qui gloriabatur luce Dei, .i. de cognicione legis. Videns eam de solio, .i. de caelo Christus, legem lauantem se, .i. exuentem figuras suas, et placuit. Tunc uocans Iudaicum populum uoluit introducere in domum suam, .i. in spiritualem intellectum legis; ille renuit et dicit, quia archa, .i. aecclesia, est in tabernaculis, .i. sub figuris, scil. quia Moyses omnia sub figuris precipit. Ideo dicit se non intrare domum, .i. in spiritum accipere alium intellectum. Accepit itaque literas mortis suae, .i. literalem intellectum, qui ducit eum in mortem, dum non uult legem spiritualiter intelligere.

This is a detailed comment on the typological meaning of the marriage between Uriah and Bathsheba. She is the symbol of the sevenfold grace of the law, while he represents the Jewish people, to which the law binds itself. The rest of the marginal gloss elaborates on the well-known exegetical trope of the inability of the Jewish people to perceive the deeper allegorical significance of the Bible (spiritualem intellectum legis), thus remaining trapped in the deadly realm of the literal understanding (literalem intellectum qui ducit eum ad mortem). The text of this gloss is copied in its entirety from the treatise Enarrationes in Matthaeum, which has been attributed to Anselm of Laon (d. 1117).13 The complexity of the argument presented in this marginal note presupposes both a higher level of Latinity and at least a basic familiarity with the medieval exegetical method. The gloss not only explains the meaning of the poetical text but also takes it to a new level of sophistication.

Occasionally, the marginal glosses become so extensive that they completely surround and even dwarf the text they are commenting upon. This situation is seen in manuscripts containing glossed Bibles and other scholastic books, where the primary compositions are copied in a confined writing block in the middle of the page, while the surrounding gloss fills the rest of the page.14 In these cases the gloss has become the main exposition, whereas the original composition which inspired it is included as a point of reference. The two textual entities are connected either through signes-de-renvoi, as we saw above, or through lemmata, that is, words and phrases from the main composition that are repeated in the commentary in order to make the reader aware which sections of the text have been subjected to scrutiny.

The margins of the manuscript page had been used for so long as useful space where notes on the main text could be written that the practice continued even after books began to be printed. Various early humanists, known and unknown, would collate in the margins of their freshly printed tomes variant readings of the text in front of them in addition to remarks of clarification and explanation. The medium might have changed but the attitude towards the page attested in these books is still the same as during the Middle Ages.15

Catena Commentaries: Becoming the Text

Whether short or long, simple or intricate, the interlinear and marginal glosses are still physically joined with the texts, which they explicate. This localized unity is broken in the so-called catena commentaries, which represent continuous chains of notes copied independently of the text they annotate, but linked to it through lemmata cues like the ones that were mentioned already in relationship to the marginal glosses. In this the catena commentaries break away from the immediacy of the text/gloss page continuum and claim the status of independent expositions, which in turn might inspire their own glossing activity. The examples of catena commentaries are numerous. The format was used for annotating both classical and scholastic texts.16 In the field of medieval biblical studies a famous catena commentary is the so-called Catena Aurea to the four Gospels compiled from various sources by Thomas Aquinas in the 1260s.17

The example presented here is from an anonymous catena commentary to Peter Riga’s poem the Aurora found in Salzburg, Stiftsbibliothek Sankt Peter, MS a.VII.6. Only a short section of this catena has ever been printed, and the excerpt below is taken from this partial edition.18 For the reader’s convenience I also give the full text of the Aurora, which is then followed by the anonymous Salzburg Glose.

| Peter Riga’s Aurora, Liber Genesis, vv. 21–36.19 Principium Iesus est; celum creat auctor in isto, |

|

| Per quem celestes efficit esse uiros. | |

| Terra prius uacua notat ecclesiam sine fructu, | |

| Donec Christus adest et sibi iungit eam. | |

| 25 | Eius in aduentu datur ecclesie noua proles, |

| Nam breuis aut nullus ad bona fructus erat. | |

| Scripture tenebras caligo figurat abyssi: | |

| Mystica scripta quidem clausa fuere diu, | |

| Sed ueniente Iesu reserauit scripta beatum | |

| 30 | Pneuma, superferri quod memoratur aquis. |

| Hinc merito sequitur quod facta luce recedunt | |

| Et fugiunt tenebre, lucida terra patet: | |

| Nempe sacri flatus reseratur claue magistra | |

| Quidquid scripture ianua clausa tenet. | |

| 35 | Lux notat a tenebris diuisa quod a tenebrosis |

| Distinguat uitiis lucida facta bonus. |

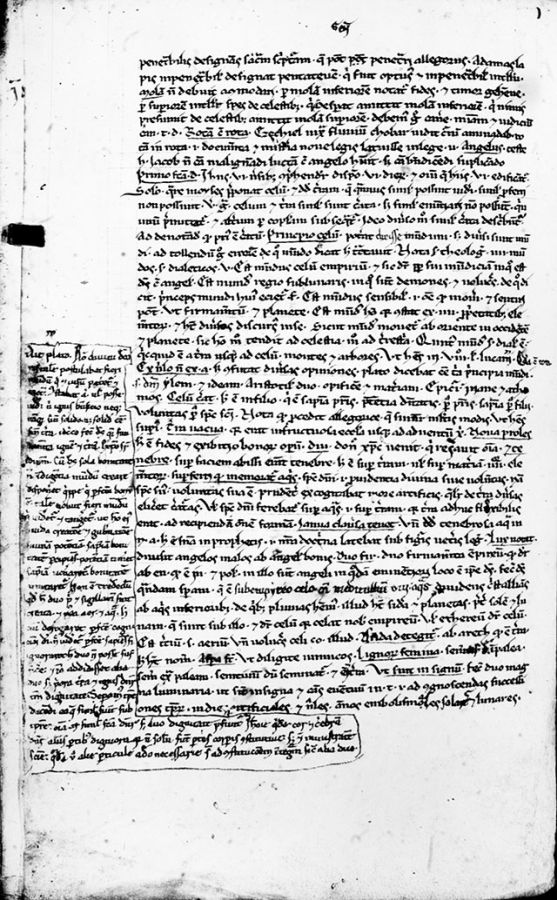

This passage from the Aurora offers the reader an allegorical interpretation of the narrative of the first day of Creation: the beginning of everything is Christ; the empty and barren earth (terra uacua sine fructu) symbolizes the Church before the arrival of the Saviour who makes her fertile with his good deeds; the shadows of the abyss (caligo abyssi) denote the hidden meaning of Holy Scripture; light separated from darkness (lux a tenebris diuisa) symbolizes the division between the bright virtues and the dark vices. The anonymous commentary on this text reads as follows (the lemmata selected by the glossator and underlined in his commentary are printed in bold typescript in Riga’s text presented above) (Plate 60.2):

Plate 60.2 © Salzburg, Stiftsbibliothek St. Peter, MS A.VII.6, fol. 49v.

celum creat, hoc est, in filio qui est sapientia patris; potentia diuinitatis persona patris, sapientia persona filii, uoluntas persona spiritus sancti. Nota quod procedit allegorice quod sumitur multis modis, ut habes superius. terra uacua, quia erat infructuosa ecclesia usque ad aduentum Christi. noua proles, hec est fides et exibitio bonorum operum. diu, donec Christus uenit qui regnauit omnia. et tenebre. Super faciem abissi erant tenebre, hoc est, super terram uel super materiam quatuor elementorum. superferri quod memoratur aquis spiritus Domini, idest prouidentia diuina siue uoluntas, nam spiritus suus uoluntas sua est; prudenter excogitabat more artificis qualiter de terra diuersas eliceret creaturas; uel spiritus Domini ferebatur super aquas,20 idest super terram, quia terra adhuc flexibilis erat ad recipiendam omnem formam. ianua clausa tenet. Vnde Dauid: Tenebrosa aqua in nubibus aeris,21 hoc est, sententia in prophetis, idest nostra doctrina latebat sub figuris ueteris legis. lux notat. Diuisit angelos malos ab angelis bonis.

It is clear from this example that, even though the catena commentary clarifies, explains, and supplements Riga’s poem, it is still very much dependent on its structure and literary expression. The gloss might look like an independent composition because of its continuously flowing text, but in reality it is not. The catena commentaries are separated from the texts they explicate physically rather than conceptually. One advantage of this format for the commentating tradition is that it removes the constraints which the limited dimensions of the page impose on the glossator and allows him to include extensive and complex comments alongside the short and simple ones. A second advantage might be related to aesthetic concerns; for whatever reasons, a glossator might prefer to leave the manuscript of the original work he is commenting upon unmarred by interlinear and marginal notes: in that case, the creation of a separate chain commentary would be the preferred working method. Finally, it should be noted that in addition to the annotations, the actual lemmata found in the chain commentaries are also worthy of study because they can exhibit textual variations that have been lost or obscured in the text’s modern critical edition. All in all, the catena commentaries contain a wealth of information about the intellectual and often didactic concerns of their creators.

Observations on Layout

The discussion presented above intimates that the different glossing systems occupy clearly defined registers on the page, i.e., the interlinear glosses are found within the body of the text and close to the words they explicate; the marginal glosses fill the space surrounding the text and are keyed to it either by signes-de-renvoi or by general proximity; and the catena commentaries represent continuous texts of explanatory notes removed from the primary composition but still linked to it by carefully chosen lemmata.

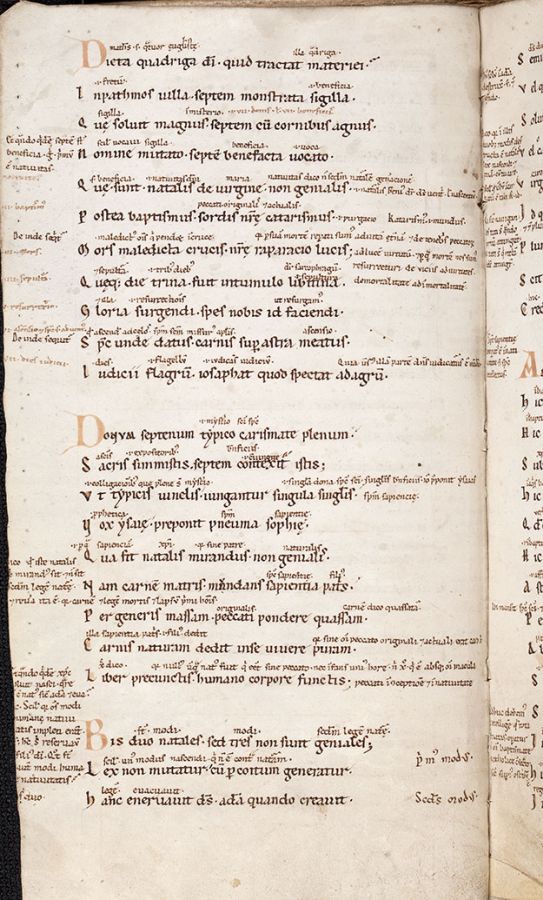

While this is generally true, the situation in medieval manuscripts is not always so uncompromising, especially in the case of the interlinear and marginal glosses, which can easily run into each other’s spatial registers. A good example of this fluidity is seen in the Liber Generationis Iesu Christi, vv. 224–7 (Plate 60.3):22

| illa sapientia patris, .i. filius, dedit | quia sine omni peccato originali et actuali erat caro Christi |

Carnis naturam dedit in se uiuere puram,

| Christus dico | quia nullus umquam natus fuit qui esset sine peccato nec infans unius hore nisi Christus qui est absque omni macula peccati in conceptione et in natiuitate. |

| Liber | precunctis humano corpore functis. |

Plate 60.3 © Heidelberg, Universitätsbibliothek, MS Salem IX 15, fol. 32v.

In the first verse the gloss explaining that the body of Christ was pure because it was free of all original and actual sin is so long that it starts as an interlinear gloss but extends into the right margin. The same is also true for the even longer note on the second verse, which continues the same argument: Christ does not have a human body like everybody else “because nobody was ever born without sin, not even an infant that is one hour old, except for Christ, who remains without any stain of sin both in his conception and in his birth.” The placement of these glosses shows that sometimes it is not easy to label a particular comment as either interlinear or marginal because spatially it represents a merging of the two.

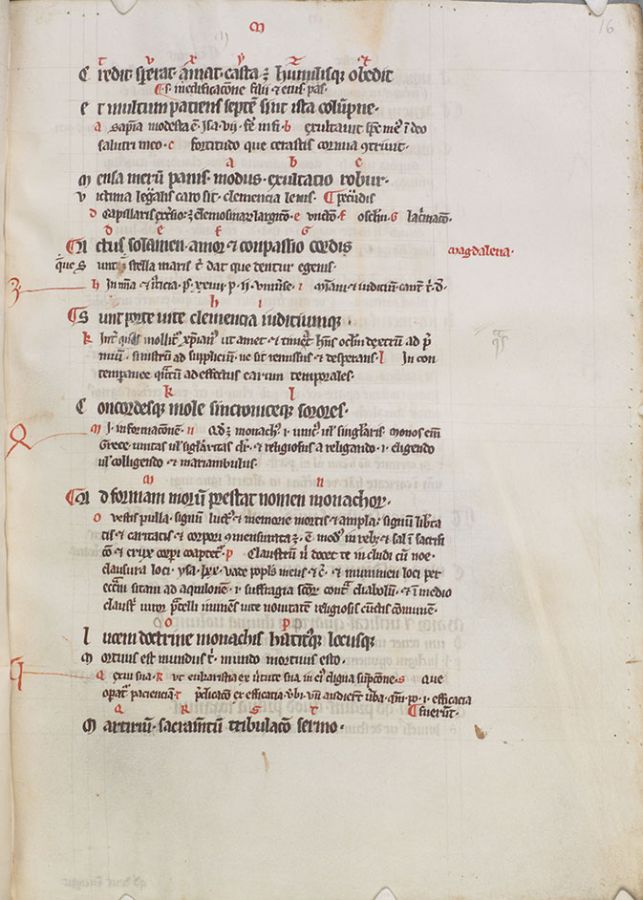

Occasionally, glosses that normally would appear in the margins of the page are gathered together into something like short catena commentaries and copied above the verse which they expound. This practice has the advantage of eliminating the confusion that could result when glosses were displaced or cue marks omitted. However, the inclusion of such extensive fields of commentary into the actual body of the poetic work interferes with the continuous reading of the text and thus suggests that this annotating format could have been meant for teaching purposes. An example is seen in William de Montibus’s Versarius, where the epigram Monachus is glossed as follows in Cambridge, CCC, MS 186, fol. 16r (the cue letters are written in red ink; Plate 60.4):23

Plate 60.4 © Cambridge, Corpus Christi College, MS 186, fol. 16r.

The various glosses and layout formats presented in this chapter demonstrate the fruitful relationship between medieval texts and their commentaries. The purpose of the glosses is first and foremost practical, but it is clear from the arrangements we see on the manuscript page that aesthetic considerations also played a role in organizing the material at hand. As a result, the primary composition and the secondary commentary are mutually shaped into a new textual reality which is both richer in meaning and more complex in form. It is simplistic to claim that glosses and commentaries were written only to provide the elucidation of obscure and difficult texts. The medieval glossing enterprise is much more than that. It represents a mode of thinking, a way of expression, and an intricate method of intellectual engagement with the inherited literary and scholarly tradition.