Chapter One: Setting the Stage

Antebellum and Civil War Western North Carolina

On September 1, 1867, Scottish-born botanist and naturalist John Muir set out from Jeffersonville, Indiana, on a “thousand-mile walk” to the Gulf of Mexico. Moving south through Kentucky and southeast through Tennessee, Muir studied and collected specimens of southern plant life. A Tennessee blacksmith could not believe that Muir—on his own volition and without a government commission—was simply walking through the recently war-torn South. As the blacksmith put it, Muir’s plan to “wander over the country and look at weeds and blossoms” made little sense in the tough times that followed the Civil War. Muir recorded his own thoughts about his voyage, including opinions about the environment and the people he discovered. “This is the most primitive country I have seen,” he wrote about East Tennessee and western North Carolina on September 17. When he arrived in western North Carolina, a Mr. Beale welcomed the traveler into his home in the Cherokee County seat of Murphy. Here for the first time since his trek to Florida began, Muir encountered “a house decked with flowers and vines, clean within and without, and stamped with the comforts and culture of refinement in all its arrangements.” It was, he mused, a stark difference from the “primitive” homes along the border.1

The region through which Muir passed has proven difficult to define culturally and geographically. Today, we call it Appalachia, a name derived from the Apalachee Indians and given to the region by French artist Jacques Le Moyne in 1564. When Muir completed his journey, however, he referred to it as “Alleghania,” a name used in the late eighteenth century. Around 1900, geographers adopted “Appalachia” as the term for the larger mountain range, encompassing the Blue Ridge Mountains as well as the alluvial Tennessee Valley and parts of eastern Kentucky. Regardless of its name, western North Carolina garnered special notice within this section of the South. The Old North State’s western counties possessed the nation’s highest peaks east of the Rocky Mountains, many of which clustered along the Tennessee and North Carolina borders near the Oconaluftee and Little Pigeon Rivers.2

Muir was not alone in traveling throughout the South after the Civil War. Unlike the small army of northern journalists, government officials, and other visitors, the plight of white Unionists, former slaves, and defeated Confederates had no interest for Muir. Even if little of the physical mountain landscape had changed as a result of the war, the social and cultural landscape had changed profoundly. The people Muir encountered had lived through the rise of an economically divided region that saw mountain slave owners, like their counterparts in the lowland South, capture the lion’s share of western North Carolina’s economic and political capital. The first half of the nineteenth century saw western North Carolinians develop strong economic ties with the southern cotton economy, which led a majority of white western Carolinians into the war for southern independence. Despite internal divisions among its population, western North Carolina contributed its share of men and materiel to the Confederate war effort. In the end, however, that conflict exploded the localized antebellum political culture. The strains of war—the absence of many military-aged white men, weakening bonds of slavery, localized guerrilla violence, strong national governmental policies—“opened” the region to a variety of external sources of power that threatened elite whites’ domination of the region.

Many travelers like Muir noted the raw beauty of the southern mountain landscape, but the region had also been home to humans for centuries. Its first residents were Mississippians, a cultural group characterized by their large earthen mounds and central temples. These earlier chiefdoms evolved into the indigenous populations encountered by Europeans in the 1500s. Spread across parts of North Carolina, Georgia, Tennessee, and South Carolina, the Cherokee were the most powerful Native American group within Southern Appalachia.3 In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, many Scots-Irish immigrants came to America to escape the rigidity of society in Northern Ireland where, like much of Europe at that time, a small landholding class exercised vast economic and political control over a landless laboring class. Migrating slowly from Pennsylvania into Virginia and western North Carolina, the Scots-Irish settled the fertile river valleys that served as the easiest means of travel and trade, making western North Carolina’s early white pioneers successful farmers and merchants. Slavery soon followed. Although some mountain masters, such as the Pattersons of Caldwell County, fit within the state’s wealthiest slaveholding population, the majority of highland slave owners fell within a middle class of commercial farmers, merchants, manufacturers, artisans, and small-scale professionals with fewer than twenty slaves. Wealthy, business-oriented mountaineers recognized the economic advantages of slavery and used the revenue from their various business ventures to purchase and employ their slaves.4

Not large planters in the same vein as slave owners in the Deep South and Cotton Belt, mountain slaveholders exhibited a level of political and economic control comparable to the broader southern gentry. One-fourth of all white families in the plantation South owned slaves and controlled over 93 percent of that section’s total wealth. North Carolina’s mountain slaveholding class also owned large amounts of land. In northwestern North Carolina, Ashe County’s eighty slaveholders owned a disproportionate 28 percent of the improved farm acreage in the 1850s. Parallel situations existed throughout the Carolina highlands, where slaveholders commanded 59 percent of the total wealth. The smaller percentage of mountain slaveholder-controlled wealth is misleading because western North Carolina slave owners made up only one-tenth of the region’s white families. Hence, mountain slaveholders possessed a higher comparative percentage of their region’s total wealth compared to their plantation counterparts.5

Yeoman farmers, who owned land but few if any slaves, constituted a far greater portion of the mountain populace. The earliest white settlers’ occupation of the rich bottomlands and reliance upon open-range livestock pushed these settlers onto less fertile land, where they settled into a predominantly local system of exchange. Whereas yeomen living in the plantation districts were often bound to local planters for economic assistance, the independent small farmers outside the Black Belt relied on one another. Large-scale agricultural projects requiring intensive labor, such as clearing trees, became community functions joining local yeomen together. Despite their settlement of more remote mountain areas, Southern Appalachian yeomen were not isolated. East Tennessee farmers shared many characteristics with their counterparts across the mountains in western North Carolina. Hog drives proved extremely profitable for farmers in both regions and served to tie small farmers to Lower South markets. Following the completion of the East Tennessee and Georgia and the East Tennessee and Virginia Railroads by 1855, the entire East Tennessee Valley had rail access. Farmers began producing wheat largely for markets. Without a railroad, western North Carolina farmers remained committed to livestock production. The absence of a viable cash crop, such as cotton, prevented the formation of typical southern plantations and promoted agricultural diversity. Rough terrain and a cooler climate allowed grains to thrive where cotton floundered. Cattle, sheep, and hogs proved especially profitable because they adjusted well to mountain conditions. In addition, cotton’s dominance in the Lower South increased the demand for foodstuffs from the Upper South. Since mountain farmers traditionally produced an abundance of food, it was only a matter of directing that surplus to market. Hence, western North Carolinians had a strong interest in the success of the staple crop.6

Landless white tenants rested below the yeomen in the southern social hierarchy. Tenancy was on the rise throughout the South during the late antebellum period. Sociologist Wilma Dunaway has argued that landless tenants were essential to the settlement of Southern Appalachia. Land speculators purchased large tracts of Southern Appalachia through the final decades of the eighteenth century, which Dunaway claims rendered three-fourths of the total acreage in the highlands the property of absentee owners. This speculative trend, begun in western North Carolina in 1783, made it difficult for small farmers to acquire land legally. Dunaway concludes that this combination of absentee owners and landless settlers “entrenched [tenancy] on every Southern Appalachian frontier.” Still, the material differences between landless whites and landowning yeomen were subtle. Both groups worked small tracts of land for personal use and raised livestock with similar rewards. Renters enjoyed a degree of freedom denied yeomen. Because their labor agreements were temporary, tenants could leave a bad situation, and they did not pay property taxes. Such benefits exacted a price. Landless tenants lacked the security and independence of the landowning yeomanry. Poor landless whites were subjected to evictions, biased written contracts that favored their employers, and the confiscation of their crops by creditors.7

Class conflict remained muted before the Civil War in western North Carolina, despite the declining position of landless whites. As was the case throughout the South, family ties eased social tensions. Intermarriage among the region’s wealthiest families fostered bonds that solidified the slaveholders as a class. For example, the influential Lenoir family of Caldwell County linked several of the western counties’ most powerful families. Revolutionary War veteran and early settler William Lenoir’s children and grandchildren brought the Lenoirs together with the Avery family of Burke County, the Joneses and Gwyns in Wilkes County, as well as their Caldwell County neighbors the Pattersons. Still, the slave-owning elite remained mindful of their largely nonslaveholding constituents. Political campaigns created personal relationships between lower-class voters and wealthier neighbors who hosted visiting candidates and organized meetings. Perhaps it was the region’s lack of a true planter class that most effectively fostered unity among mountain whites. Though mountaineer masters dominated the region’s politics—87.1 percent of the men elected to the state legislature between 1840 and 1860 owned slaves—their diverse economic interests created common ground with their community. Middling and lower-class whites in the upcountry and mountain sections supported slaveholders politically because they pushed for the region’s recognition and development at the state level. More broadly, the slaveholders’ promotion of states’ rights staved off outside power—primarily the federal government—and allowed lower-class whites more autonomy within their lives and communities.8

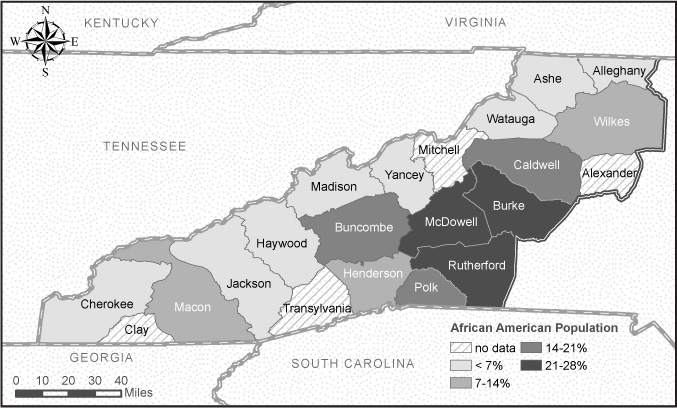

MAP 2. African American Population in Western North Carolina, 1860. Map produced by Andrew Joyner, Department of Geosciences, East Tennessee State University.

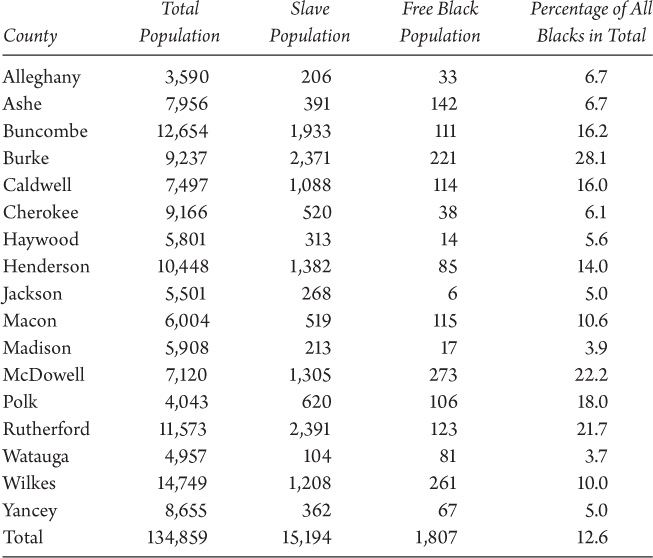

Slaves occupied the lowest rung on the social ladder in the southern mountains, just as they did throughout the South. Yet African Americans in the western counties lived differently from their plantation counterparts. One reason for the difference was mountain slaves’ comparatively small percentage of the population (see Map 2 and Table 1). The white majority feared slave rebellions less and allowed their chattel more mobility throughout the region. Some mountain slaves served as guides for summer tourists. Slave owners in western North Carolina were less likely statistically to employ corporal punishment, and also less inclined to separate slave families through sale. Still, such benefits only altered, not negated, the exploitive characteristics common to the southern slave system. For example, historian Edward Phifer found sexual exploitation of slave women as common in Burke County as elsewhere in the South. Neither did living in western North Carolina remove the psychological scars inflicted by being classified as property.9

TABLE 1 African American Population in Western North Carolina Counties, 1860

Note: Clay, Mitchell, and Transylvania Counties formed in 1861. See Corbitt, Formation of the North Carolina Counties 1663–1943, 67, 149, 204.

Sources: Inscoe, Mountain Masters, 61; and Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research, Historical, Demographic, Economic, and Social Data (computer file).

While the basic contours of society in the mountain South paralleled the section as a whole, mountain residents generally outpaced their lower-elevation compatriots in their support for internal improvements. Western North Carolinians believed their region was on the rise, and they urged the state to support projects that facilitated their growth. Turnpikes, such as the highly traveled Buncombe Turnpike completed in 1828, became a top priority in the 1830s and 1840s. But opposition from the eastern part of the state—such sectional rivalry within the state was a defining trait of the state’s antebellum politics—threatened western development. Eastern North Carolinians refused to pay the taxes necessary to fund such projects because they failed to see how they benefited from western improvements. The discovery of valuable mineral resources in southwestern North Carolina and East Tennessee’s success with mining and railroads led western Carolinians to explore all possibilities to obtain their own railroad. By the 1850s the issue garnered such popular backing that both mountain Whigs and Democrats supported it. Finally in 1855, western North Carolina secured a charter and a $4 million state appropriation for the Western North Carolina Railroad (WNCRR). That high price, however, forced the construction of the road in segments, with the completion of one part to precede the construction of the next.10

During the 1830s and 1840s, the Whig Party’s commitment to internal improvements contributed to the party’s consistent popularity in western North Carolina; however, an economic depression limited the state’s spending power for much of that period. One Whig member of the state assembly believed that North Carolina would have to raise taxes fivefold in order to finance its desired internal improvements, an unsavory idea for any politician. Consequently, the Whigs were unable to deliver funding for improvement projects during that time. Realizing that proposed railroads through western North Carolina by both South Carolina and Virginia would divert mountain trade out of the state, Democrats dropped their opposition to state-funded internal improvements. The Whigs’ inability to receive public funds for western improvement projects, along with the orchestration of the WNCRR’s creation by a Democratic governor, hurt but did not destroy them. By 1860, the Whigs had slipped in terms of their influence within western North Carolina, but their commitment to internal improvements sustained them as political players in the mountains even after their national party collapsed in the mid-1850s.11

Two political issues heightened the state’s internal east-west rivalry and stirred class tensions during the late antebellum period. The state constitution apportioned the upper legislative house according to taxes paid and the lower house based on federal population, including slaves as three-fifths of a person. This system concentrated power in the plantation-dominated eastern counties. In 1848, Democratic gubernatorial candidate David Reid proposed the elimination of the property qualification that limited the political voice of lower-class Carolinians. Mountaineers demanded a constitutional convention to convert the basis of representation in the lower house to conform to Reid’s proposal. Failure to support the convention weakened the mountain Whigs and brought Reid’s Democrats to power in the state. Chastised by the voters, Whigs regrouped in a convention in Raleigh in 1850. The resulting pamphlet known as “The Western Address” challenged the dominance of a propertied—especially slaveholding—elite at the expense of lower-class whites. By the end of the antebellum period, the Whigs further regained lost ground through support of ad valorem taxation, touted by Whigs as “equal taxation.” Eastern planters opposed the proposal because it would tax all slave property according to value, whereas the existing poll tax only assessed male slaves between twelve and fifty years old. Although nonslaveholders became indignant that their wealthier neighbors would not carry their share of the tax burden, the Democrats successfully convinced nonslaveholders that ad valorem taxation represented governmental encroachment upon individual property rights and would increase the taxes on all property—not just slaves. Still, the issue helped restore the two-party balance in the mountains on the eve of disunion.12

The turbulent presidential election of 1860 revealed white western Carolinians’ complex self-image. Although westerners within North Carolina, their opposition to the Republican Party in the 1860 presidential election revealed them as southerners within the United States. In western North Carolina and the South, the election centered on John C. Breckinridge, a southern rights Democrat, and John Bell, of the moderate Constitutional Union Party. A few mountaineers backed Democrat Stephen Douglas of Illinois, but the majority limited their choice to either Breckinridge or Bell, the candidates believed to have the best chance of defeating the “Black Republican,” Abraham Lincoln. Breckinridge won the state by approximately eight hundred votes, but the continued Whig influence carried Bell in the mountains. Five counties (Burke, Haywood, Polk, Rutherford, and Yancey) gave a majority to Breckinridge, while ten (Alleghany, Ashe, Caldwell, Cherokee, Henderson, Jackson, Macon, McDowell, Watauga, and Wilkes) supported the Constitutional Union Party and John Bell. Western North Carolina’s support of a middle-road candidate closely resembling a Whig did not represent a weaker commitment to southern rights. Both parties in the mountains and the South favored the continuation of slavery, the protection of which remained the focus of political debate. From this perspective, the election more clearly represented western North Carolinians’ continued adherence to two-party politics.13

South Carolina’s withdrawal from the Union on December 20, 1860, following Lincoln’s election, magnified the secession controversy in North Carolina. Congressman Thomas Lanier Clingman led the mountain secessionists. Clingman emerged in the late 1840s as an “ultra-Southern” politician, and his status as the senior member of the state’s congressional delegation reflected western Carolinians’ sectional loyalty. To the nonslaveholding majority, Clingman and the secessionists predicted economic ruin if Appalachian North Carolina broke with its Lower South trade partners. Secessionists also appealed to mountaineers’ racial fears. They warned that Lincoln would destroy slavery if white southerners did not unite to stop him. Furthermore, Clingman warned that thousands of freed slaves would flood into western North Carolina once slavery was abolished. He knew his constituents. North Carolina mountaineers shared the same racial outlook of white southerners elsewhere. White highlanders agreed that slavery represented the proper condition of inferior African Americans. Nonslaveholding mountaineers may have disliked the slaveowners and slaves that devalued free white labor in the eastern part of the state, but compared to emancipation, slavery appeared the proper course in their minds.14

The secessionists’ emotional appeal swept some mountaineers into their camp, but most highlanders preferred a “wait and watch” approach to the crisis. Hesitation to secede did not reflect a widespread affinity for the Union. Mountaineers viewed the Union as a means to an end rather than an end in itself; they adhered to it as long as the federal government guaranteed their interests as individuals, North Carolinians, and southerners. Unconvinced that disunion was the best means to protect their interests, western Carolinians rejected the call for a state secession convention by a 54.8 to 45.2 percent vote in February 1861. Furthermore, western Carolinians elected twelve pro-Union candidates to the secessionists’ five. Unlike the extreme secessionists of the Deep South, the majority of mountaineers believed that the election of a Republican president did not endanger slavery or necessitate the state’s withdrawal from the Union. Western North Carolinians and much of the Upper South, however, made it known that they would not tolerate the use of force to restore the Union. Lincoln’s call for seventy-five thousand volunteers to quell the rebellion following the surrender of Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor destroyed western North Carolinians’ Unionism. Forced to choose between the Union and the South, western Carolinians joined with their eastern counterparts in favor of disunion on May 20, 1861.15

Western Carolinians’ final decision to unite with the Confederacy derived from a variety of sources. The most important was the perpetuation of African American slavery. Conditional-Unionist Whigs argued that the Constitution protected slavery while secession threatened it. Secessionists, on the other hand, pointed to Lincoln’s stance against the expansion of slavery and claimed that the Republican Party truly intended to destroy the institution where it already existed. Whatever side of that argument one fell on, white western North Carolinians knew slavery was a central part of their lives. White highlanders not only shared the racial views of the South; they benefited from the tourism dollars rich slaveholders brought to their region each summer. Furthermore, they understood that the profits they realized from each hog drive to South Carolina and Georgia markets had a lot to do with slaveholders’ demand for foodstuffs. Mountaineers believed that they needed slavery in order to achieve their region’s economic potential following the advertisement of their natural resources, improvement of their farming techniques, and the continuation of its internal development. Democratic leader William Holland Thomas of Jackson County pronounced the Confederacy the best means to that end. Thomas believed, “The mountains of North Carolina would be the centre of the Confederacy. We shall then have one of the most prosperous countries in the world. It will become connected with every part of the South by railroad. It will then become the centre of manufacturing for the Southern market. The place where the Southern people will spend their money, educate their children and very probably make laws for the nation.”16

Throughout the spring and summer of 1861, thousands of male western North Carolinians left their families and friends for southern-armed service. Women hosted picnics and showered soldiers with gifts as they marched to war, reminding them that they were the defenders of southern honor. Such displays reinforced mountain men’s conviction to defend their homes during the months following secession. The high concentration of relatives and friends in volunteer units also strengthened the palpable need to defend their homes. During the first two years of the war, the high concentration of family members within volunteer units bolstered national loyalties by giving them a local flavor. The men’s absence from home, however, would challenge their commitment to fight on distant battlefields. Unionist raids from across the Tennessee border on their unprotected homes imbued male western Carolinians with a healthy anxiety for their families.17

Public displays of unity masked lingering divisions within mountain society. Gordon B. McKinney has identified layers of loyalty within the mountain counties: consistent Unionists, consistent Confederates, conditional Unionists, neutrals, and those without any opinion on the divisions between North and South. His analysis of postwar amnesty petitions suggests that more than 40 percent of the petitioners were either neutral or held no opinion on the war at all. Conversely, the petitions also reveal a roughly equal percentage of consistent Unionists (20.69 percent) and Confederates (15.71 percent). That balance broke, however, when the 22.22 percent of conditional Unionists who supported the Confederacy after secession are factored into the equation. The most outspoken petitioners were the hardcore Unionists, who endured harassment, intimidation, and even violence for their sustained loyalty to the United States, which they placed in close association—but above—their familial responsibilities. Consistent Confederates did the same, placing the South and Confederacy atop their local relationships. Conditional Unionists argued that their state merited first consideration, regardless of their personal feelings on disunion. Those mountain residents who tried to remain above the fray did so to protect their families and their community from the horrors of war.18

During the war’s first year, white mountain women faced the same crisis that confronted white women in other sections of the South. In the mountains, where the nuclear family constituted the basic economic unit, the absence of skilled and unskilled male laborers was especially damaging. Women hesitated to sustain their husbands’ Confederate service as the war outlasted early hopes for a brief conflict. Men’s absence forced women to assume men’s agricultural work on top of their own labors. Mounting economic hardships undermined the paternalistic covenant, in which women deferred to men in exchange for protection. Increasing sacrifices symbolized men’s, and in a larger sense the Confederacy’s, failure to provide properly for their women. A mounting guerrilla war in the mountains further convinced some mountain women that they could neither be taken care of nor be physically defended. With so many men gone, they felt defenseless.19

North Carolina’s competitive two-party system created a political outlet for mountaineers’ rising dissatisfaction. The 1862 gubernatorial election captured the state’s drift from the pro-secession enthusiasm of the previous year. A new Conservative Party arose under the leadership of newspaper editor William W. Holden, a leading Democratic proponent of antebellum reform, and conditional-Unionist Whigs, who initially opposed North Carolina’s secession. The Conscription Act of 1862 created the attraction for this political marriage of old opponents. Unionist-Whigs hesitated to support the new party until the adoption of conscription, which they saw as the birth of a strong military state at odds with individual liberty. In the beginning, Conservatives drew heavy support from lower-class whites, resentful of Confederate governmental policies that seemingly favored the wealthy by exempting one white male on every farm possessing twenty or more slaves. Equally galling was the provision allowing wealthy white southerners the ability to hire substitutes. Yeomen and landless whites across the South cried out in protest of what they perceived as a “rich man’s war and a poor man’s fight.” These claims resonated in North Carolina’s western counties, where fewer farmers could afford to pay their way out of military service.20

Conservatives’ need for someone to unite their coalition led them to Zebulon B. Vance, a Buncombe County native, former Conditional-Unionist Whig, and Confederate colonel. During the campaign, the Conservatives used Holden’s powerful North Carolina Daily Standard newspaper to woo voters. They portrayed the secessionists as radicals who led the people out of the Union without a plan to handle the exigencies of war. Thanks to Vance’s broad appeal and Holden’s influence, the Conservatives won the governor’s chair in convincing fashion. Vance won more than 90 percent of the vote in five mountain counties, including an impressive 97.8 percent in Ashe County. Almost 73 percent of the state, and 87 percent of mountain voters, rejected the secessionists and made Vance their governor.21

An escalating guerrilla war exacerbated growing tensions. Fearful of East Tennessee Unionists and unwilling to serve in the regular army, pro-Confederate partisans appeared as early as July 1861. An influx of deserters from both armies further inflamed passions. Although many of these deserters were western North Carolinians returning home to aid their struggling families, the mountains attracted other fugitives who saw the rugged landscape as an excellent hiding place. Some of these men organized partisan bands aimed at their self-defense, the protection of their families, and prosecution of their cause. The guerrillas’ presence emboldened Unionists who transformed loyalist counties, such as Wilkes and Caldwell, into centers of resistance. When the Sixty-Fourth North Carolina Infantry Regiment entered Madison County during the winter of 1862–63 to arrest deserters, it resulted in tragedy. Angered by the bushwhacker tactics of concealed guerrillas and a raid on their colonel’s family, the Confederate troops determined that the best way to deal with such Unionists was to kill them. They subsequently rounded up thirteen suspects between the ages of thirteen and fifty-nine and marched them out of town. Once safely outside town limits, they lined their prisoners along the road and executed them.22

Fallout from the Shelton Laurel massacre and the Confederates’ retreat from Knoxville, Tennessee, further destabilized the region. Knoxville’s occupation gave U.S. forces and Union partisans greater access to western North Carolina. Raids intensified during the latter half of 1863, turning Wilkes County into an irregular battlefield. Unionist John Quincy Adams Bryan made no secret of his Unionist loyalty, which helped turn his Trap Hill community in the northern part of the county into a haven for deserters, disaffected Confederates, and others loyal to the United States. From this hodgepodge group, Bryan formed something resembling a military company that traversed the countryside harassing residents and skirmishing with the Home Guard, a state military organization that policed communities for deserters, guerrillas, draft evaders, and other enemies of the Confederacy. Irregular military activity and violence carried over into 1864. Andrew Johnstone, a rice planter from South Carolina vacationing in the North Carolina mountains, was murdered. Home Guard forces proved ineffective at restoring order, so Governor Vance sent additional Confederate forces into the mountains. Over the course of six weeks, the regular reinforcements aggressively hunted deserters and Union sympathizers.23

Unionists and Confederates confronted enemies in their communities. The Shelton Laurel incident underscored the dangerous conditions in Madison County, where property was routinely confiscated. Sidney McLean’s experience demonstrates the dangers confronting Madison residents. The pro-Union McLean lost two horses, 750 pounds of bacon, 200 pounds of flour, and large amounts of corn and beef to Union raiders despite his fidelity to the United States. Federal forces commandeered his property for the cause; Confederates targeted his person for local control. Desperate for manpower, Rebel Home Guards arrested McLean and forced him into the southern army. A bout of illness forced the Confederates to discharge him without his performing any service. Numerous times during the war’s final three years, McLean “was both threatened and injured as to my family and property, and was actually molested and injured.” In the spring of 1864, Confederate colonel J. A. Keith, one of the officers responsible for the Shelton Laurel massacre, directed his men in a raid that “destroyed my [McLean’s] household furniture, and either killed, or drove off, all my live stock” and forced his family from their home along Bull Creek. Angry and frustrated with his inability to protect himself and his family, McLean escaped to the Federal base in East Tennessee. When he next set foot in Madison County, he wore the single gold bar of a Union first lieutenant.24

Public protests against the Confederate government’s infringements on civil rights across the state in July and August 1863 laid the groundwork for a political split between Holden and Governor Vance. Both defended individual liberties and agreed that North Carolina should fight as long as it remained vulnerable to invasion, but Holden favored a negotiated armistice with the North. At an impasse, Holden challenged Vance in the 1864 gubernatorial campaign. Public exposure of Unionist organizations, such as the Heroes of America, working secretly in tandem with the peace movement during the final month of the campaign destroyed Holden’s chances for victory. Founded in central North Carolina in 1861, the Heroes of America, who were active in the mountain counties by 1864, performed espionage, encouraged desertion, and escorted Unionists to Federal lines in East Tennessee and Kentucky. In the 1863 election for the Confederate Congress, the Heroes likely coordinated Rutherford County resident George W. Logan’s successful campaign as a peace candidate. From 1864 to the war’s end, the Heroes of America supervised local Unionist networks and may have become overtly political. Although unhappy with Confederate policies and increasing wartime sacrifices, mountaineers stood by the “War Governor of the South.” Vance secured over 75 percent of the mountain vote and his second landslide victory. Holden managed a scant margin of victory—51.5 to 48.5 percent in Unionist Wilkes County—while Vance dominated the remaining counties. Other than Wilkes County, Vance polled no lower than 60 percent in any other western county.25

Vance’s victory did not end people’s suffering or heal divisions within the state. An absence of male laborers combined with droughts, hog cholera epidemics, and the effects of the war drove hungry highlanders to take matters into their own hands. In April 1864, fifty women in Yancey County broke into a Confederate supply warehouse and carried off sixty bushels of wheat. Slavery remained relatively intact in western North Carolina during the war, but that did not stop upland slaves from engaging in subversive activities. During the war, slaves exploited their mobility and knowledge of the landscape to help fugitive Federal prisoners from Salisbury avoid recapture. Other African Americans fed, clothed, and hid enemies of the Confederacy or escaped to Union lines themselves. Still, such opportunities for escape were limited in western North Carolina, where the Union army was not a major presence until Knoxville’s capture in September 1863.26

The general insulation of mountain slavery from the strain of war largely preserved the power of white masters until the end of the Civil War. Highlanders bought or leased slaves in increasing numbers to work on private farms and public improvements such as the WNCRR. Mary Bell of Macon County purchased her family’s first slaves in February 1864. Encouraged by her husband to convert their cash holdings into a tangible investment, Mary acquired a servant girl whom she swapped for a slave family a few months later. Her pride in the acquisition, completed so late in the war, accentuated western Carolinians’ belief that the institution was both stable and safe. Amid a war that included emancipation as a Union objective, slavery prospered in North Carolina’s mountains, seemingly oblivious to the surrounding world.27

With mountain society already at war with itself, a large-scale Federal intrusion into the region finally occurred in the war’s last year. In February 1865, George W. Kirk, a Union colonel from East Tennessee who garnered a reputation as a bushwhacker and guerrilla in western North Carolina, pushed his regiment of mounted infantry into Haywood County, where they tangled with William Holland Thomas’s Confederate legion of white and Cherokee troops. Kirk’s six hundred or so men amounted to little more than a nuisance. When combined with a larger push to apply constant pressure throughout the Confederacy, however, the alleged bushwhacker had a more profound impact. Union major general George Stoneman, onetime head of the Union Army of the Potomac’s cavalry, launched a massive raid into North Carolina from East Tennessee as part of the Union leadership’s plan for a final drive to victory. Stoneman’s primary objective was the military prison in Salisbury, North Carolina, which he hoped to destroy and from which to liberate its prisoners. Although Kirk and Stoneman failed to free Salisbury’s prisoners, they did successfully spread fear and panic throughout mountain communities.28

As they marched through the mountains, Stoneman’s men applied a formula toward civilian property familiar to North Carolinians who experienced William T. Sherman’s march through the central portion of the state a few months earlier. Stoneman and his chief subordinates sought to deprive white southerners of items they needed to wage war, but they tried to discern between loyal and rebellious citizens in their efforts. Residents’ efforts to comply with the wishes of the Federal officers may also have lessened the impact of the war’s hard hand.29 Still, even the most loyal of white men paid the price of war during the war’s final months. A pro-Union doctor in Alexander County, John M. Carson, saw his home near Taylorsville converted into a Union camp in April 1865. Despite Carson’s aid given to Union prisoners fleeing the Confederate prison in Salisbury, roughly one hundred Union soldiers confiscated his property.30

The hard hand of war made no distinctions for race or gender as it embraced Carson and his neighbors. Elijah Jennings, who lived near Mulberry in Wilkes County, lost a horse and bridle in late March 1865 to a handful of Stoneman’s men while he plowed his fields. Fellow Wilkes resident John Glass lost a horse to the Federals around the same time.31 A Unionist widow, Elizabeth Jolley, lost supplies to the Confederate Home Guard, and then Stoneman’s men seized her mare.32 As Betty Ann Hamilton’s husband garnered praise for his service in the Union’s Second North Carolina Mounted Infantry, his family lost a horse to the Federal cause in April 1865. Mary Merrill, who like Hamilton resided in Henderson County, sent her husband and sons to Tennessee to escape the Confederate ranks. Her sacrifice to the Union neither halted her harassment by local Rebels nor prevented the loss of her horse to the Federals.33 Though Union soldiers confiscated loyal mountaineers’ property, it bears noting that the Federals acknowledged that loyalty by providing receipts for the items they took.

Perched on the precipice of freedom in the spring of 1865, black mountaineers’ bodies and property were not exempt from war’s cruelty. In Buncombe County, Isaac Garrison worked a small plot of land granted him by his owner. Isaac earned the respect and appreciation of the local Unionists whose families he provided with invaluable aid. Regardless, slaves such as Garrison and free black men, such as John Chavers of Wilkes County, also saw their property carried off by Federal soldiers. The approach of Union soldiers prompted Confederates to descend upon Chavers’s farm and seize two hundred bushels of corn, bacon, and a variety of home furnishings and clothing. Union soldiers added insult to injury when a Yankee squadron took two horses.34

The dealings between the soldiers and the communities in their path ran the gamut from general peacefulness to sheer terror. Morganton, the Burke County seat, resisted Stoneman’s men. Some eighty Confederate Home Guards and regular Confederate officers tried to stave off the Yankee column under Arlen Gillem, who was in no mood to compromise with western Carolinians. Once the cavalrymen forced their way into the town, they unleashed an onslaught of looting, plundering, and destruction. Typical of such scenes was the treatment afforded Robert C. Pearson, a local banker and railroad official. Lower-class ruffians described by one observer as “false to their God and traitors to their country” ransacked Pearson’s home.35

Again, it was the level of local resistance encountered by the Union horsemen that precipitated the treatment given Asheville. The Buncombe County seat was a major economic center by the standards of the western region, but it was still a relatively modest town. It was home to many of the North Carolina mountains’ wealthiest and most successful merchants, it served as a staging point for the herding of livestock south along the Buncombe Turnpike, and hopes grew during the late antebellum period that it would one day serve as the major western hub for the WNCRR. During the war the Confederates had an armory and training camp as well as a commissary, hospital, and post office in Asheville. For those reasons, local troops rallied to its defense and hoped to block the approaching enemy at Swannanoa Gap.36

At first it appeared this vital economic center might escape the pattern of destruction that Stoneman’s Raid wreaked elsewhere in the region. Federal general Gillem and Confederate general James G. Martin met early on April 24, 1865, on the town’s outskirts to discuss rumors of Joseph E. Johnston’s surrender at Durham Station, North Carolina. It appeared that the war was finally over, and Gillem pledged to pass peacefully through Asheville en route back to Tennessee. For his part, Martin promised rations and safe passage to the Yankee cavalry. Residents breathed a collective sigh of relief as the roughly 3,000 soldiers in blue passed through peacefully on April 26. Asheville inhabitants barely had time to relax before the situation changed drastically. Federal cavalrymen raced their horses through the streets, chasing women and searching for men. Troops rounded up all the Confederates they could find and ransacked the homes of community leaders. Late in the afternoon, General Samuel B. Brown’s Yankee soldiers set their torches to the former site of the Asheville armory. Finally, on April 28, the Federal troopers set off for Tennessee, and Asheville and western North Carolinians at large could exhale.37

Wars expose a society’s fault lines, creating new problems and exacerbating existing ones to the point that the very earth shakes beneath people’s feet. Whether they were conscious of it or not, the war changed white western North Carolinians’ agricultural foundation. Hundreds of thousands of hungry soldiers forced Confederate policymakers to enact controversial tax policies like the tax-in-kind and impressment that transferred resources from community to national control. Under the tax-in-kind or tithe, farmers were responsible for turning in one-tenth of their crops and one-tenth of their bacon to Confederate officials who redirected it to the military. By 1864, Confederate tax assessors transferred three-quarters of the 300,000 rations of flour, 50 million rations of corn meal, and several thousand head of cattle to the troops. Of the roughly $40 million worth of tax-in-kind goods collected, North Carolina, Georgia, and Alabama contributed nearly two-thirds of the total. Armies in blue and gray were less discerning, simply taking what they needed when they needed it. Deserters, guerrillas, and other disaffected residents also stole food and other property throughout the region. Regular forces offered little protection. James Longstreet’s Confederate troops put an additional burden upon western North Carolinians on their way back to Virginia from East Tennessee in 1864. Finally, a large-scale Union cavalry raid under General George Stoneman liberated valuable livestock and personal property from their highland owners in the spring of 1865.38

Western farmers had little time to bemoan their misfortunes when the war ended. Most farmers, like E. A. Davis of Wilkesboro, busied themselves with the challenge of making ends meet. Davis’s “attention as well as every one [sic] else’s in this country has been taken up with putting in and tending crop” with no “leisure to trade and indeed nothing to trade.” At least Davis had a positive view of the future. “Corn looks well, croakers [complainers] to the contrary notwithstanding,” he wrote in the early summer, “and although the newspapers assert that ruin and starvation stare us in the face, I see no evidence of it in this poor country.” One such “croaker,” Unionist Calvin J. Cowles, surveyed his county’s farms for the federal Department of Agriculture in the fall of 1866. His findings contained some good news. Bad weather failed to impair the oats crop, which stood ready to double while Cowles estimated that sorghum would quadruple. Wilkes County farmers also increased the production of tobacco, no doubt hoping to reap a financial boost from growing twice the amount previously. What they relied upon to feed themselves and their families, the region’s two most vital agricultural goods, corn and hogs, both fell well below normal levels. According to Cowles’s estimates, Wilkes County had less than half the number of hogs fattening in 1866. Worse still, those hogs were of poor quality. Corn suffered an equally frightful decline, and Cowles noted that it was drying up. Although Cowles noted a slight improvement in the condition of the corn in September, he added grimly that the county’s cattle were well below normal standards. Wilkes residents possessed 20 percent fewer cattle in September 1866 than they did in 1865, and, like the county’s hogs, they were of inferior quality.39

Western North Carolinians also faced significant demographic changes as a result of the war. Slavery was a casualty of the war across the nation. While the slave population fluctuated during the war, emancipation meant that approximately fifteen thousand African Americans—or approximately 11.3 percent of the population—would gradually realize freedom in the Carolina mountains. According to one estimate, western North Carolina sent 1,836 soldiers into the Union army and 26,000 men into the Confederate ranks. Almost six thousand of the Confederate troops died in service. Coupled with the loss of men in the Union and Confederate armies, these changes foreshadowed significant changes in western North Carolina. While the larger number of Confederate soldiers reflects the highlands’ predominantly pro-Confederate sympathies, the given estimates obscure the ambiguity of men’s loyalty. Donning a uniform in service to one’s country can be a clear sign of devotion, but not everyone who volunteered for Confederate or Union service stayed in the ranks for the duration of the war. Many Confederate volunteers joined the army in order to gain access to the Federal ranks. Other men deserted midway through the conflict as the realities of war exceeded their expectations. Such shades of gray made an assumption of mountaineers’ loyalty to one side or the other far from clear after the war.40

Finally, the political future of the region was also cloudy. Zebulon Vance’s decisive 1864 gubernatorial election showed the strength of the war wing of the Conservative Party, but with the Confederacy’s fall it was far from certain who would rule the state. It was unclear what shape the state’s comparatively strong two-party system would take. The Conservatives who led the state through the war stood humbled and uncertain of the future. Their leader, Governor Vance, was arrested and confined to Old Capitol Prison in Washington, D.C. Supporters of the peace movement barely challenged Vance in the 1864 gubernatorial contest, but it would have to be seen if the governor’s decisive majority reflected majority opinion or if those mountaineers opposed to the war were stifled and afraid of voicing their dissent publicly. Neither was it clear that there existed anything approaching unity among the state’s disparate Unionist citizens.

Peace would prove as divisive and complicated as the war itself. Political coalitions collapsed and returned upon the uncertain foundations of wartime loyalties. Outside power entered the region as well. Efforts to reconstruct the South brought Federal soldiers and agents into every section of North Carolina. The state’s political parties were in flux. Conservatives rallied around Vance and the Confederacy in 1864, yet with the war over the future of that party as well as the region’s Unionist minority was uncertain. Local tensions remained high as veterans returned to a community infested with deserters and guerrillas, some of whom swore vengeance upon their neighbors for wartime acts. Nothing made sense in this time of uncertainty and suspicion, as John Muir discovered on his walk through the South. When he entered Cherokee County in September 1867, the sheriff stopped him because “every other stranger in these lonely parts is supposed to be a criminal, and all are objects of curiosity or apprehensive concern.” Strange faces were objects of close scrutiny for good reason. Few mountaineers knew exactly whom they could trust or whether old friends remained true. None of the mountain towns Muir visited still smoldered by the time he passed through, but the scars of war and the suspicions that followed remained apparent to even the most transient of visitors.41