Chapter Four: Agents of Change

The Freedmen’s Bureau, 1867–1868

As poetry goes, it was nothing special. Spoken by an unnamed composer at the Washington School in Raleigh on June 27, 1867, “North Carolina Free” captured the excitement and hope of African Americans as well as white Republicans at a particular moment in time. Once Congress assumed control over Reconstruction, the military—though reduced in number following a rapid demobilization in 1865 and 1866—possessed greater power in the occupied South. The presumably black poet praised the war for ending slavery and keeping the Old North State within the Union, and rejoiced in a future enlivened by freedom stretching “From Mitchell’s Peak to Hatteras Banks” and “From Curritank to Cherokee.” Congress’s Reconstruction Acts and the military’s presence were two reasons for that hope, but the Freedmen’s Bureau proved more significant for the African Americans living nearer to Mitchell’s Peak and Cherokee. Bureau agents’ arrival in western North Carolina offered hope for secure labor as envisioned in the poem and protection from violence. Opportunities awaited the former slaves who, the poet noted, were “free to plow, to fell, to mine; Our hands and homes are all our own.” A future of secure family households and schools, like the one where the verse was read in Raleigh, and full citizenship seemed within reach. An alliance of white Republicans, black voters, and federal power in the hands of bureau agents proved to be the means to that end in North Carolina’s western counties.1

The composer also spoke of freedom to work, own a home, and study the Bible, and although he or she portrayed the war as a distant past, the fact was that federal power was closer to North Carolinians than ever. Congress’s Reconstruction Acts in the spring of 1867 imbued federal agents and officers across the South with great power extending down from above. Grassroots organization reached up to meet the deepening federal presence in western North Carolina. Postwar attempts to organize anti-Confederates that had begun in the northwest with the resurgent Heroes of America, or Red Strings, continued as white southern Unionists joined the Union League, a northern organization that spread throughout the South after the war. But whereas anti-Confederate leaders once hailed the country as belonging solely to white men, their organizations demonstrated a shift in their thinking in 1867 and 1868. Republican organizations in western North Carolina—and across the state—opened to white and black highlanders after Congressional Reconstruction began. For instance, the Buncombe County Union League led by Unionist Alexander H. Jones had councils and 1,800 members by August 1, 1867. A separate roster for the “Colaard Leag” in Buncombe County revealed at least forty-four black members, including several with familiar last names like Henry, Love, Jones, and Erwin. Rutherford County had 1,200 Union Leaguers, and Burke County had a strong league presence as well. The presence of biracial political organizations revealed that Republican politics in western North Carolina would take on a newly inclusive racial tone. Political affairs now became the purview of both white and black men.2

Congressional Reconstruction altered the course of the Freedmen’s Bureau’s efforts in western North Carolina. When Andrew Johnson oversaw southern Reconstruction, the military presence in the North Carolina mountains was weak. The bureau had been sympathetic to mountain blacks, and its agents worked to mediate labor contracts and disputes when they could, but a lack of personnel, local opposition, and the military’s scant presence limited its influence. Once Congress assumed control, the more Freedmen’s Bureau agents, most of whom were white northerners with bureau experience elsewhere in North Carolina, arrived in the mountains.3 Though scattered throughout the region with minimal direct military support, bureau agents drew efficiently and effectively on both the troops they had and the threat of military power. These officials became the conduit of federal power for mountaineers of all races, providing protection, food, and other means of support. To be sure, black mountaineers did not need the bureau to teach them where their best interests lay. Black southerners across the region determined for themselves what they wanted and needed in the wake of emancipation. In areas where blacks constituted a distinct population minority and lacked the means to achieve their goals on their own, however, the bureau was a powerful ally and facilitator of interracial political cooperation. African Americans continued to rely on the bureau to safeguard their political and civil rights, but whites also came to depend on the agents for support after March 1867. Frustrated white Republicans embraced blacks politically after the Conservatives won control of local and state offices. Hence, a stronger, more active bureau brought together African Americans and white Republicans, making possible what many historians have held as sacrosanct about Southern Appalachia: that it was a Republican stronghold.4

A significant step toward strengthening the Freedmen’s Bureau in western North Carolina was to expand its reach. Qualified personnel were in short supply after the war, and keeping the few agents in the west proved difficult. Lieutenant P. E. Murphy received a transfer to Greensboro and left Asheville in June 1866. Western District head Clinton Cilley also stepped down from his post that summer and mustered out of service completely on September 1. Each subdistrict needed a reliable agent. During the summer of 1867, such agents emerged from the Veteran Reserve Corps, which kept severely wounded and disabled veterans on active duty during the conflict. Three new agents came to western North Carolina from this organization. Special orders in June 1867 assigned First Lieutenants George S. Hawley and James F. Allison to Macon and Wilkes Counties, respectively. Allison, who had previously worked for the bureau in Tarboro, North Carolina, opened an office in Wilkesboro on September 24, 1867. Second Lieutenant William N. Thompson, also of the Reserve Corps, arrived in Ashe County in mid-July. While the bureau relieved civilian agents that June in Caldwell and Henderson Counties, it sent Oscar Eastmond, a New Yorker who served as lieutenant colonel in the First North Carolina Union Infantry in eastern North Carolina, to replace Lieutenant Murphy in Buncombe County. Along with Hannibal D. Norton, who remained on duty in Morganton, these officers gave the bureau a strong presence in western North Carolina.5

Each agent did his best to uphold the protections established for African American workers in the first two years after the war. In Asheville, Lieutenant Murphy’s successor proved particularly aggressive in his duties. When black mountaineers forced issues like unpaid wages and child apprenticeships onto the political agenda, Oscar Eastmond wielded the bureau’s authority promptly in their favor. A local black man, Campbell Leadbetter, came to Eastmond’s office to complain that his landlord, John Murphy, had concluded a contract with him the previous year in which Leadbetter was to receive one-third of both the corn and wheat as payment. Eastmond ordered Murphy to appear at his office within two days and to do nothing with the disputed crop. Failure to comply, the agent warned, would result in Murphy’s losing all his corn and wheat. Similar issues plagued John Jordan, whose white landlord withheld his pay. John R. Bennett rented a piece of land and a house to the freedman, but once the crop matured, Bennett drove Jordan off. Eastmond sympathized with freedmen in such battles because whites proved less than accommodating. Too many whites behaved like Thomas Patton, who Eastmond wrote had a reputation for “ill treatment of freedmen in not paying them their wages.” Patton preferred to delay payment and court proceedings to the point where the former slaves’ money ran out. Two black men complained to the bureau that they lacked the financial means necessary to sustain legal action against Patton. Although Eastmond knew these cases belonged in the civil courts, he recognized the injustice in Patton’s using freedpeople’s lack of means against them and asserted his own authority in order to give them a chance at redress.6

Eastmond also became a part of African Americans’ efforts to bring their families together. Although many freedpeople went back to work on their former owners’ farms, others had their children wrested from them by discriminatory apprenticeship practices. Black mountaineers resisted these efforts and turned to the bureau for help. Apprenticeship made clear that even in western North Carolina where blacks were a distinct population minority, whites both craved their labor and wished to retain their mastery over them. In Buncombe County, where African Americans made up roughly 16 percent of the population, James Horton had two of Dicy Pendland’s children, Zeb and Julia, bound to him against the wishes of their mother. Eastmond tried to help; he ordered Horton to appear in his office on August 9. Noncompliance would result in Horton’s arrest and trial before a military court “on the charge of forcibly depriving said persons of their liberty.” Eastmond took similar steps to cancel the indenture of a young black woman named Margaret Miller. White landlord Jeff McMenn responded in a manner reminiscent of slavery; he claimed her labor since he had “paid money for her and has her bound to him.” Eastmond sided with the girl’s parents, who wanted her returned to them.7

A stronger Freedmen’s Bureau reshaped the political landscape in western North Carolina. In Rutherford County, the only mountain county to send representatives to the 1865 freedmen’s convention in Raleigh, a local newspaper announced its support for its black readers. The Rutherford Star urged black men to stand strong against threatening and delinquent landowners. As “freemen,” black residents needed to fight for and assume the basic rights of citizenship, including the rights to collect their rightful pay for labor performed and vote. If their employer threatened not to pay them or to evict them without settlement, the Star exhorted its black readers to join the Union League and to vote the Republican ticket. White men who refused to pay black workers for their labor, the newspaper reported, risked bringing the Freedmen’s Bureau’s wrath down upon themselves. This editorial first ran in Rutherford County, but the staunch Unionist-Republican, Alexander H. Jones, reprinted it in his Pioneer, which had recently relocated to Asheville. When Jones ran this piece on August 20, 1867, the name Oscar Eastmond was already becoming anathema to local Conservatives.8

Eastmond was not alone in the effort to secure the rights of freedpeople in the Carolina highlands. Lieutenant George Hawley was a Freedmen’s Bureau veteran by the time he arrived in southwestern Macon County in 1867. Dealing with child apprenticeships was not new for Hawley, confirmed by the air of authority in his letter to John Sanders, who held a young African American named Isaac on his farm. Sanders worked the boy hard without granting adequate provision for him. Isaac desired to leave Sanders’s employ, but his white landlord compelled him to stay. “You are hereby informed that such retention of the freed boy is illegal,” Hawley warned, “rendering you liable to punishment according to the laws of the United States.” Should Isaac wish to leave, Sanders must allow him to do so. Any additional attempt to retain Isaac against his will would be at Sanders’s “peril.” The Macon County agent informed the landlord that the best way to avoid “serious consequences” was to pay Isaac for services rendered and to let him go.9

James F. Allison also went to work settling wage claims in his district upon his arrival in Wilkesboro in September 1867. During the next two months, he adjudicated several such disputes. On October 24, he informed Richard Nicks that he owed Irvin Hall $26 that he could either pay or appeal. Just over two weeks later, he accused William Finley of depriving Peter Staley use of a mule and $250 for the loss of Staley’s crop. Allison expanded his reach beyond recent events. In the case of an African American named Pompey Dobson, the agent sought a settlement from 1865. He charged Elisha Wellborn of defrauding Dobson of $17.41 for labor performed. A similar situation confronted Miles Sperer. Previous efforts on the freedman’s part to collect his wages had failed, so Allison intervened. Either pay the $40 Sperer claimed, Allison warned, or appear in person to refute the charges. To cap the year’s work, Allison instructed two other white proprietors to settle accounts with an African American named Philip McCordy of Alexander County. McCordy claimed that both white employers owed him almost $20.10

A willingness to correct past wrongs invigorated western North Carolina’s Freedmen’s Bureau agents during Congressional Reconstruction. Oscar Eastmond came to Asheville partly for health reasons. He hoped that the salubrious mountain climate would ease the respiratory ailment he contracted during his war service in eastern North Carolina.11 His greater motivation for accepting the bureau post, however, was his belief that reconstructing the South required drastic action and that southern Unionists needed federal assistance. On June 10, 1865, Colonel Eastmond asked permission for his men in the First North Carolina Union Infantry Regiment to keep their guns after they mustered out of service because former Confederates remained dangerous. After all the southern-born Union soldiers had sacrificed and accomplished, Eastmond hoped the government would not leave them “to the mercy of those from whom both themselves and families have suffered taunts, and violence during the rebellion—men who have burned their homes, desolated their plantations and simply left what they could not destroy, the land.” He felt certain that “secret plots of midnight violence and highway murder” would follow.12 Confirmation of his fears came quickly. Early in July 1867, the Henderson Pioneer reported an attack on members of Asheville’s Union League. This incident outraged Republicans. Pioneer editor Alexander H. Jones chastised Conservatives for tacitly condoning the stoning by doing nothing to punish the assailants and condemned Asheville as “the hot-bed of rebellion in this section of the State.” In his estimation, “there are more ‘Booths’ than one in the land ... encouraged by technical phrases and insinuations” to do harm.13

Eastmond also condemned local Conservatives’ inaction. According to Eastmond, these county officials were not merely ignoring orders; he interpreted their inactivity as open resistance to federal authority. In disobedience with bureau orders, white judges proclaimed publicly that they would not allow black testimony in their courtrooms. Attempts at enforcing black testimony in civil courts would contradict state law banning it, and the judges vowed to resign rather than disobey state law. When he forwarded the Pioneer’s report to his supervisor, Eastmond indicted local officials by association. Disregard for authority and political violence convinced him to take matters into his own hands.14

His conviction that Conservatives oppressed all their opponents—black and white—prompted a showdown between Eastmond and Buncombe County’s political elite. North Carolina civil courts long conflicted with the bureau’s mandate to protect black males’ civil rights, including the right to testify in state courts. The denial of that right to a freedman named Camy Spears, charged with theft and assault after the war, brought Eastmond into direct conflict with local Conservatives. Spears’s lawyer insisted that his client acted under duress from three white men, allegedly Union soldiers, but the Conservative-controlled county court harassed Spears at every turn. It twice issued warrants for horse theft dating back to April 25, 1865. It was Spears’s forceful binding to a local Conservative, however, that caught Eastmond’s attention. The agent accused Judge Augustus Merrimon and Solicitor David Coleman of acting inappropriately, an accusation the prosecutor denied vehemently. What galled Eastmond was the court’s rejection of Spears’s testimony because it was illegal for African Americans to testify in court according to North Carolina law. Found guilty, Merrimon and Coleman gave Spears the option of negotiating privately with someone to pay his fine, which Natt Atkinson, a local white Conservative lawyer and Judge Merrimon’s brother-in-law, did in exchange for the freedman’s bound labor.15

Prominent Buncombe County Conservatives played a critical role in Spears’s conviction, and their actions revealed their political motives. Merrimon and Coleman both protested Eastmond’s involvement feverishly. The agent’s reversal of a civil court action challenged Conservatives’ local rule, and Merrimon and Coleman feared that Eastmond’s interference might inspire other Unionists, blacks, and Republicans to follow suit. Ignoring his own possible nepotism in the affair, Judge Merrimon declared that the agent’s actions showed the county’s black population and “worst men” that they could disregard civil authority with impunity. Solicitor Coleman predicted that the conviction’s reversal would create “wild” and “unlawful” thoughts among Buncombe County blacks. White Conservatives feared that Eastmond had opened a Pandora’s box of racial and political catastrophes and that African Americans would follow his example of resistance.16

While Conservatives viewed Eastmond’s actions as an affront to their local control, they failed to deter him. According to Solicitor Coleman, the Asheville agent felt that the court and community dealt unfairly with blacks and had assumed personal responsibility for “setting them right.” On August 8, Eastmond informed Atkinson that his arrangement with Spears was an outrage. Atkinson’s rebuttal revealed his own belief that the Conservatives, as the “best men” in the county, should determine their former slaves’ fate. He defended the trial and urged the agent to “hear the evidence of the witnesses for the State and understand who they were.” Unmoved, Eastmond countered that his own investigation revealed that the state’s witnesses were unrepentant traitors, and now that he had some troops to support him, he would set things right. Back in Eastmond’s office, Captain Jeremiah C. Denney of the Fifth U.S. Cavalry listened to Spears’s side of the story. Atkinson again tried to persuade them to abide by the court’s decision to no avail. Spears went free.17

Aiding Camy Spears was only the beginning for the erstwhile Asheville agent. Eastmond also took up the cause of Mitchell Hayden, a black man cheated in a land deal and then twice beaten by angry whites in Madison County in the winter of 1866. In late September 1867, Eastmond resubmitted Hayden’s petitions for relief to his superiors. The commanding general of the Second Military District responded to the renewed pressure with orders to arrest the African American’s attackers. Previous efforts had failed to apprehend the responsible parties, but local whites noticed the increased scrutiny and pressure that accompanied a stronger Freedmen’s Bureau in their community. Since the federal authorities took up Hayden’s case, they had captured one man. The other guilty parties sent emissaries to Eastmond with an offer to pay Hayden $100 and enter a $5,000 bond to keep the peace in exchange for their freedom. Eastmond replied that he lacked the authority to solemnize their proposal, but he “suggested that all the guilty parties surrender themselves to me ... acknowledge their guilt, and then enter upon their parole, to appear at any time when called upon.” Seven men subsequently surrendered, and Eastmond dutifully submitted the plan to the military to judge “whether one hundred dollars will sufficiently pay the freedman for his injuries and the United States Government for the time trouble and expense it has been put to in this case.”18

Eastmond viewed the military and bureau as tools to reconstruct the South, with the military serving as both arbiter and enforcer of the law, and he used that power to punish other criminals who had previously escaped justice. In March 1868, he informed Colonel George A. Williams that Hannah McElroy, the freedwoman strangled and robbed by Harvey Roberts in 1866, still had not received relief. Despite her being hanged by the neck three times and left terrified of future attack, the county court did little to protect McElroy or alleviate the black community’s broader concerns about protection. A county court consisting of three white men levied a five-dollar fine upon Roberts for the assault. Local officials made an equally weak effort, Eastmond reported, to do justice to William and Lewis Young, who tried to reclaim a young family member held by Solomon Luther’s family. Although Luther had previously owned the boy and produced a document from Eastmond’s predecessor binding the young worker to him as long as the boy wished to stay, the new Buncombe County agent sided with black parents’ custody claims. Both father and son behaved peaceably, but the white family set upon the black men and beat them. Despite several family members facing charges for two assaults, only one of them received any punishment—a mere five-dollar fine. While local Conservatives seemed to have found a value for beating their African American neighbors—five dollars—the Freedmen’s Bureau agent proved equally determined to obtain justice.19

Agents throughout western North Carolina used the bureau’s authority to monitor local courts. Often their actions helped the Republican Party. In Wilkes County, James F. Allison intervened on behalf of white Republicans involved in the July 4, 1867, Wilkesboro riot. A Wilkes County grand jury indicted several men—including John Peden and Leander Gilreath, who pled guilty—for their roles in the riot, but the solicitor, J. M. Cloud, introduced nothing against either Peden or Gilreath in court in early November. Allison was dumbfounded that at the trial “not the slightest evidence could be adducted to convict them.” Once Peden and Gilreath realized that the tide had shifted in their favor, they attempted to rescind their guilty pleas. Solicitor Cloud’s refusal to let them out of their initial pleas gave rise to what Allison termed “the crowning piece of rascality” in which the court “conspired with the Defdts to get the plea of guilty removed by openly suggesting it in Court.” Solicitor Cloud again objected, so the court meekly fined Peden and Gilreath five dollars each. “And this is all the penalties imposed by the Judiciary,” an exasperated Allison informed the military commander in Salisbury, “for assaulting and dispensing a quiet and peaceable Meeting of Unionists.” The riot itself predated Allison’s tenure in western North Carolina, but his clear sympathies for the Unionists and Republicans in his district led him to suggest reversing the court’s decisions.20

Efforts to protect the rights of the former slaves and to bolster the power of local Republicans helped bridge the gap between white and black mountain Republicans. Included in the military’s mandate in the Reconstruction Acts was the registration of voters for the election of new state and national officials and delegates to a state constitutional convention. The acts also reorganized the former Confederate states that rejected the Fourteenth Amendment into five military districts commanded by a major general with oversight authority in state affairs. General Daniel Sickles, commanding the Second Military District of North and South Carolina, turned to Governor Jonathan Worth, who recommended men to organize voters in the Old North State. While Worth worked to appoint registrars, however, so did the Freedmen’s Bureau. The bureau’s involvement in such an important state matter deeply agitated the governor. Burke County lawyer Burgess S. Gaither suggested two Union soldiers to Worth as “the best [registrars] under the circumstances.” Angry over the slow decay of his authority under Congressional Reconstruction, Worth erupted. “Select your men with the sole view of their fitness and qualification,” he chided Gaither, “and in conformity with the directions of my circular.” Bureau agents balanced the boards of elections according to race, appointing at least one African American man in each district. No such appointments were necessary under the governor’s order of April 20, 1867. Reminding Gaither indirectly that he—not the bureau or other federal authorities—governed the state, Worth urged him to “find three honorable men ... who can take the oath and who would impartially perform their duty.” “If such [men] cannot be found in the County, it is better to recommend somebody out of it,” Worth directed; otherwise the matter would be left to “malevolent partizans.”21

The battle over voter registration and the local boards of registration represented a critical struggle between mountain Republicans and their opponents for local control. Republicans sought the registrar positions because they offered a modest stipend and increased their party’s influence. Registrars controlled who could vote, which marked a reversal in local power away from the Conservatives. Men such as Goldman Hagins of the Cherry Lane community in Alleghany County actively pursued the posts. He submitted a petition signed by twenty-eight neighbors and a letter of introduction from William Holden to General Sickles in the spring of 1867 endorsing his candidacy for one of the spots in his county. Hagins and his supporters represented him as the only justice of the peace who refused to take a loyalty oath to the Confederacy after secession and as a “faithful and tried friend” of the U.S. government. For his part, Holden backed Hagins as “one of my correspondents during the rebellion” and a man whose loyalty to the Union was unquestioned. In the end it worked and Hagins was appointed.22

A petition from the Conservatives in the Pigeon River community in Haywood County revealed how seriously mountaineers took voter registration. They painted a dour portrait of affairs in their county, accusing local Republicans of conspiring against them and the state. An alleged ringleader in this Republican conspiracy was A. W. Garrett, who represented Haywood in the 1865 constitutional convention. According to the petitioners, Garrett handed a slate of suggested registrars to the military commander in Morganton as well as to the local Freedmen’s Bureau agent. Local Conservatives denounced the two white men and one African American man that Garrett recommended as having “taken the secret oath to support the extreme Radical party,” and the Conservatives protested against such men overseeing the election. What most alarmed the Pigeon River folks was the increasing biracial makeup of the mountain Republicans. The Republicans’ insistence on an African American registrar, overseeing the voting rights and actions of white men, posed an immediate and direct challenge to white and Conservative control. Haywood County’s Conservatives feared the worst of the deepening Republican organization in their midst, which they felt threatened all who refused to join the Union League with the confiscation of their property. “But since the Radicals has [sic] commenced organizing their leagues and denouncing all men that dont go in with them as disloyal and threatening confiscation and taking the negro in to their meetings and on their committees,” the Conservatives charged, “the veins of many men begin to tighten and the blood flow to the face and he fears blows will follow before registration and the Election is over.”23

Registration concluded for the coming elections in October 1867, and its results proved an invaluable political lesson for all North Carolinians. While the white population retained a sizable edge among registered voters across the state, it was not a decisive advantage. The state registered 117,431 white and 79,445 African American voters once the bureau completed its task. At first glance, the white electoral edge seemed insurmountable in the mountain counties. White mountaineers constituted 86.4 percent of the region’s registered voters, far outnumbering the official black electorate of 3,323 (see Table 2). Such numbers also paralleled the region’s demographic makeup, with black voters numbering a slightly higher percentage of registered voters than they totaled in the 1860 population. White mountaineers’ electoral power proved far from decisive in practice as a result of their political divisions. A fair number of black voters in Burke, Buncombe, Rutherford, Henderson, and McDowell Counties stood ready to act as a swing vote in close elections. While far from the cries of “negro domination” emanating from white southerners in decidedly black sections of the state, white Conservatives still worried about the potential impact of expanded suffrage.24

North Carolinians did not wait long to learn what effect the changes in the electorate might have on state politics. As the political tide rolled toward the state Republicans, a referendum took place over November 19 and 20, 1867, on whether to hold a new state constitutional convention as well as to elect delegates to the proposed convention. Frustrated and angry at the federal government’s intrusion in state affairs, many Conservatives across the state opted to skip the election altogether. The result was a signal victory for pro-convention elements and a decided Republican advantage in the body’s makeup. Nearly three of every four participants in the election supported a convention, and 107 of the 120 men belonged to the Republican Party. Fifteen of that number were African Americans. Their Conservative neighbors denounced many western delegates as radicals—and three of the twenty western men had served as registrars for that election. Two additional representatives had served in the 1865 constitutional convention, including W. G. B. Garrett, whose Haywood County neighbors had condemned him previously as too radical to Governor Worth.25

TABLE 2 Registered Voters in Western North Carolina Counties, 1867–68

County |

White % |

African American % |

Alexander |

83.7 |

16.3 |

Alleghany |

90.3 |

9.7 |

Ashe |

94.5 |

5.5 |

Buncombe |

81.5 |

18.5 |

Burke |

71.1 |

28.9 |

Caldwell |

83.5 |

16.5 |

Cherokee |

96.3 |

3.7 |

Clay |

96.9 |

3.1 |

Haywood |

92.1 |

7.9 |

Henderson |

81.2 |

18.8 |

Jackson |

92.4 |

7.6 |

Macon |

94.2 |

5.8 |

Madison |

95.0 |

5.0 |

McDowell |

78.3 |

21.7 |

Mitchell |

93.2 |

6.8 |

Polk |

79.2 |

20.8 |

Rutherford |

77.2 |

22.8 |

Transylvania |

88.4 |

11.6 |

Watauga |

95.6 |

4.4 |

Wilkes |

89.5 |

10.5 |

Yancey |

94.5 |

5.5 |

Total |

21,156 |

3,323 |

Percentage of Electorate |

86.4 |

13.6 |

State Total |

117,431 |

79,445 |

Source: North Carolina Standard, November 25, 1868, 3.

This turn of events infuriated North Carolina’s Conservative governor, who believed that the military, the Freedmen’s Bureau, and the state’s Republicans all desired to topple his administration. A personal letter to a family member fully captured the extent of Worth’s venom toward the entrenching Republican presence in his state in December 1867. Congressional Reconstruction threatened both his state and the country with a monetary crisis, the governor argued, and squandered the excellent opportunity to settle affairs in the war’s wake. The governor believed that “the negroes work better now than they will in future” and that “with free negro labor we will never prosper.” “If the miserable set of jackasses,” he continued, “from Generals down to the Freedmen’s Bureau men, were withdrawn and we were allowed to re-organize the militia and pass and enforce a stringent vagrant act—even if we were compelled to give transportation to every negro desiring to move to any of the negro loving States, to which they might be desired to remove, we would rapidly recuperate.” Worth saw “no rational ground of hope while Radicalism rules.” “In giving us Canby for Sickles,” the governor bitterly griped, “the Prest. swapped a devil for a witch.” Having written the president about these issues, Worth relished a possible showdown, vowing never to become “a subservient serf for the sake of office.”26

African Americans’ creation of local institutions, particularly schools, intensified the frustration and anger felt by Conservatives like Worth who believed the former slaves would work faithfully if not interfered with by outside influences. For black southerners, education was a significant aspect of freedom, and they pursued it passionately. About a month after Congress seized control over Reconstruction, a field report revealed four schools serving 127 black students in bureau-supported schools in Buncombe, Burke, and Henderson Counties. These three counties, with their larger black populations, experienced an influx of African Americans to their county seats, which invigorated education as well. In Asheville, two schools under the direction of Thomas Hopkins and Amy Reynolds served forty and forty-one students, respectively. In Morganton, Sarah E. Pearson taught sixteen students, although Martha C. Avery thought the white Miss Pearson’s enthusiasm might wane once fifty black men surrounded her in a small classroom at night. Meanwhile, Reverend John Tyler had thirty pupils attending his school in Hendersonville. The local black community—not northern charitable societies or governmental organizations—financially supported each of these schools, a reflection of both the bureau’s limited role in black education during Presidential Reconstruction and the freedpeople’s overwhelming desire for education.27

Upon their arrival in western North Carolina, agents in other counties found efforts to form schools in various stages of progress. On September 25, 1867, Wilkes County agent James F. Allison planned to tour his subdistrict “to facilitate the organization of Freedmen’s Schools of which there is a great lack in this County as well as those adjoining.”28 What he found pleased him. The black population in Alexander County had forged ahead in their desire for schools independent of the bureau. In Rocky Springs, A. J. Stevenson ran an informal school “with fair success.” In Taylorsville, the county seat, he met A. J. McIntosh, who shared a “lively interest in the education of the freedmen” with the local black community. Still, Allison regretted that the Alexander County folks had been unable to purchase land or a building. F. A. Campbell offered to sell local African Americans a house they could convert to a school, which Allison seized upon as an opportunity for the bureau to make a difference. He reported “no other suitable building in Taylorsville ... can be rented for the purpose mentioned,” nor could he suggest a suitable alternative “for the expenditure of the appropriation allowed for that Co.” Allison undoubtedly felt optimistic about the future of black education. Alexander County was further along than he expected, and he found Alfred Stokes running a temporary school for twenty students upon his return to Wilkesboro. Once purchased, Allison opined, the school could move to the Burton estate and become permanent.29

The impact of the Freedmen’s Bureau on black mountaineers’ education efforts was equally significant in the southwestern counties. Prior to George S. Hawley’s arrival in 1867, African Americans in Macon and surrounding counties struggled to establish their own schools. Hawley and the onset of Congressional Reconstruction brought a stronger federal presence into their communities, and black mountaineers harnessed that power for their benefit. In November 1867, Hawley stated that the freedpeople of Macon County had established both a building association and a committee to spearhead efforts to erect a school. The committee sold subscriptions and had raised $150, but the bureau constituted a major component in their fiscal plan. Local African Americans “have requested of the Bureau thro me,” Hawley wrote, “such pecuniary aid as the Assistant Commissioner may be enabled to grant.” Hawley calculated that within two miles of Franklin there were sixty black children “who need the advantages afforded by a school,” and he predicted that he could find a building to serve them “at a reasonable price.”30

Success bred expansion in both hope and scope. By mid-December, Allison confidently reported five schools operating in his district. Republican leader Alfred Stokes taught the thirty-seven students at the “flourishing” Poll Bridge school in Wilkesboro. Two other Wilkes County schools in Fishing Creek and Briar Creek served twenty scholars each. Stephenson continued running his Rocky Springs school in Alexander County, while Allison happily added J. J. Duly’s school in the Caldwell County seat of Lenoir to the list in his district. With model operations in place and with more confidence in his ability to help, Allison offered new ideas for places where schools should open. He advocated the opening of three more Wilkes County schools, located at Trap Hill, Lytle Hickerson’s farm, and the Ferguson’s settlement. Taylorsville, he added, needed another school. Finally, the agent promoted the idea of two new schools at Kings Mountain and the Patterson factory in Caldwell County. Perhaps to convince his superiors these goals rested firmly within the realm of the possible, he concluded that nothing beyond what he proposed “would be required to perfect the educational system in this Sub Div.”31

Through the final days of 1867 and the early months of 1868, George Hawley worked with freedpeople in North Carolina’s southwestern corner to realize their own education dreams. Progress was slow. Only his district’s extremely limited resources could match its great need for schools. No schools existed in Clay, Cherokee, Macon, and Jackson Counties for African American children in January 1868. The black residents of Clay County desperately wanted to build a school for the approximately sixty African American children in the county, but their parents and neighbors could only raise some $50 toward its construction. Those labors bordered on the Herculean, but fell roughly $500 short of what Hawley believed necessary. In a letter to the bureau’s education superintendent in early March 1868, Hawley emphasized that the agency represented mountain blacks’ best hope for education. He admitted that his new post was unlike his previous work in eastern North Carolina. “There are but few freedmen in the counties,” Hawley noted, “but it is desirable that they be aided in their present condition, in providing for the education of their children, to the end that they may be fitted to enjoy more perfectly the blessings of freedom.” To help make this a reality, Hawley tried to acquire land in each county for a school building and lobbied the Freedmen’s Bureau for as much as $400 more to complete the process in each county.32

For the most part, the bureau played the role of advocate for mountain blacks’ education. Most of the organization and financial burden for operating the schools fell on local African American communities. The bureau agents, however, had access to outside charitable organizations and federal funds. When the agents took up the role of advocating their districts’ development, they extended black highlanders’ support network beyond western North Carolina. They put the local community in contact with outside donors and raised awareness to the black communities’ efforts for education, but they also contributed to the buying and building of schools. Hannibal Norton’s extension of funds to James McElrath, an African American, to build a schoolhouse in Burke County serves as a good example. Mountain agents rarely paid for teachers, but they did help the African Americans within their districts build schools and create an infrastructure for education.33

The Freedmen’s Bureau’s primary objective was to aid the freedpeople in their transition to freedom, but that did not mean that they were indifferent to whites. Aiding refugees and other suffering whites was also part of its mission. In overwhelmingly white Southern Appalachia, this relief effort proved a useful tool in reconnecting disaffected southerners to the federal government. Many western North Carolinians struggled after the war to feed and provide for their families as a result of the loss or destruction of foodstuffs. R. J. Hardin of Jefferson declared that thirteen white families and ten black families in Ashe County would “be compelled to suffer” from lack of food and clothing because of the wartime depredations of both armies. James Gwyn of Wilkes County noted a “great cry for corn in some parts of the country.” Transylvania County state senator Leander Sams Gash asked for help from Governor Worth in the spring of 1866. With 209 destitute families in Henderson County, which Gash attributed to high levels of grain distillation in North and South Carolina, the state senator hoped Worth could direct northern charitable aid to his counties. Worth pointed Gash to the Freedmen’s Bureau—and the state legislature passed a resolution asking the bureau for rations. Such aid was consistent with the bureau’s mandate to aid refugees and southerners grappling with the war’s end. Agents had issued rations to white southerners regularly during Presidential Reconstruction. While he oversaw the entire Western District of the Freedmen’s Bureau in 1866, Clinton A. Cilley administered aid to destitute whites without orders.34

A traditional mountain enterprise exacerbated the scarcity noted by bureau agents throughout the western counties. Homemade spirits enlivened social events—from corn shuckings to dances—and provided a viable economic option for more remote mountaineers. Counties such as Wilkes, Burke, and Ashe produced thousands of gallons of booze a year as farmers opted to distill their crops rather than endure an arduous journey to market. Burke County alone produced twenty thousand gallons of whiskey in 1860. Distillers became a problem during the Civil War as corn and other resources became sparse. State officials tried to prevent food shortages as well as preserve valuable war resources by regulating distillation. Peace failed to end scarcity in western Carolina, which exacerbated the distillation problem. State Senator Gash proposed a tax on whiskey in the hopes of curtailing production, but those efforts proved futile.35

It was with no small amount of relief that state authorities bequeathed this issue to the federal officials, notably the Bureau of Internal Revenue and the military. Major General Sickles, in his inimitable fashion, assumed the regulation mantle bullishly. On May 20, 1867, Sickles’s General Orders No. 25 barred the distillation of grain in North and South Carolina in order to preserve food resources, stop the harassment of federal revenue collectors, and ensure the collection of taxes. Anyone distilling—or in possession of a still—faced a military tribunal. Subsequent General Orders No. 32 limited the sale of “a license for the sale of intoxicating liquors in quantities less than one gallon, or to be drank on the premises” to innkeepers. Although local communities controlled the process of obtaining licenses and any fees associated with them remained separate from federal revenue laws, Sickles called for the appropriation of all licensing fees “exclusively for the benefit of the poor.”36

General E. R. S. Canby, who inherited these policies when he succeeded Sickles in September 1867, was also a strong opponent of distillation. Shortly after assuming his post, he wrote E. A. Rollins, the Internal Revenue commissioner in Washington, D.C., that the continuation of Sickles’s order was “essential to preserving peace and order.” The anti-distilling order reflected the need to conserve food resources in his district and to ensure U.S. revenue, and he informed Rollins that it had helped reduce the price of corn by 50 percent as well. Enforcement remained a challenge as Canby’s military force was already near its breaking point and civil courts rarely found distillers guilty.37

Federal relief efforts proceeded haltingly over the following year. In March 1867, Jacob F. Chur wrote a concerned Rutherford County resident that it was “impracticable under the pressing wants of other localities to send more than 50 bushels of corn to Rutherford County.” In Ashe County, Daniel Worth sought aid through northern charitable donations, and he secured two hundred bushels of corn from Philadephia’s Southern Relief Association. Later that summer, the state headquarters earmarked military rations for Morganton and instructed Hannibal Norton there “to form a committee of Ladies who will take charge and distribute any stores or monies that may be sent you.” In June, the Morganton post distributed much-needed relief to both white and black mountaineers throughout its district. Suffering white families received 291.5 military rations plus 16,234 pounds of corn and 2,332 pounds of pork. Those numbers dwarfed the aid provided to black highlanders. Compared to their white neighbors, they received 11 rations, 616 pounds of corn, and 88 pounds of pork. Over the final two weeks of the month, mountain whites received an additional 168.5 rations, while African Americans received only 59.5. Lopsided relief for whites continued through the summer. The ratio was 80 rations given whites and 44 for blacks in July.38

Western North Carolina agents supported similar relief efforts. Between September and November 1867, William Thompson in Ashe County distributed fifty rations to people in his district. In November, Eastmond requested clothing for the “indigent and infirm colored people” as the need for men and women’s clothing became acute. Despite the fact that few destitute people lived in his district, Eastmond classified those indigent living nearby as “extremely so.” Aid for the poor reached into the southwestern counties as well. In Franklin, agent George Hawley reported four specific cases of impoverished mountaineers, three of which were white. Mabel Mathews, a sixty-three-year-old white woman, possessed no means to provide for herself or her widowed daughter and four grandchildren. Two other white residents, William Love and Sarah Williams, were either unable to work or sick. The lone freedperson recorded by Hawley as needing relief was Litty Ledford. The middle-aged Ledford suffered from rheumatism and was “entirely helpless.”39

Want and scarcity continued and perhaps even increased through the winter of 1867 and 1868. Residents of Cherokee and Clay Counties informed agent Hawley that both white and black citizens faced precarious prospects that winter. Hawley’s informants speculated that “a large number” of mountaineers—both black and white—in Cherokee and Clay lacked the food reserves necessary to weather the winter, which, combined with a low labor demand, greatly weakened local economies and the people’s buying power. They looked to Hawley and the bureau to stave off “great suffering and perhaps starvation” among the poor because the civil government failed to meet poorer citizens’ needs. Hawley twice requested permission to purchase supplies in December 1867. “No provision has been made by the Wardens of the Poor,” Hawley wrote, for the impoverished inhabitants of Cherokee and Clay Counties. Without his immediate aid, it seemed some mountaineers might die.40

With many North Carolinians mired in poverty and struggling for survival, the political focus of the state shifted to Raleigh, where the new constitutional convention opened on January 14, 1868. Despite being the second such convention in three years, this assembly differed greatly from its predecessor. African Americans’ presence and the Republicans’ domination of the proceedings—that party constituted 107 of the 120 delegates—guaranteed changes in the state’s governing document. Picking up where the 1866 convention left off, delegates declared secession illegal, repudiated the state’s Civil War debts, and banned slavery. They also denied the governor the power to suspend the writ of habeas corpus, a clear response to the Confederate government’s suspension of that right during the war in order to suppress wartime Unionists and other dissenters. The representatives further cemented their alliance with the national Republican Party as well. They followed the national legislature’s lead by proclaiming all men equal and granted the right to vote to any man—white or black—able to swear allegiance to the United States, while barring those guilty of treason, perjury, or dereliction of duty while in office previously from the polls. Support for education under the new constitution became an official state responsibility. During the antebellum period, North Carolina created an adequate public school system, but alarmist whites raised the specter of integrated schools following emancipation. In May 1866, state legislators had abolished the public schools because the state’s Literary Fund was bankrupt and to avoid public education for African Americans. The new constitution overcame that obstacle by mandating a capitation tax to support both education and poor relief.41

When the convention adjourned on March 17, 1868, it was clear that western North Carolinians—both black and white—would benefit from the new constitution. New executive offices included a lieutenant governor, a state auditor, and of particular import to internal improvement advocates in the west, a superintendent of public works. This office offered the hope for continued development of roads and railroads to increase the marketability of mountain crops and mineral resources. Also of interest to the mountain counties was the proposed change in the composition of county government, which became elective in North Carolina for the first time. No longer would the ruling party in the state legislature appoint local officials. A five-person commission in each county, elected by the people, became the locus of county government. Furthermore, the commissioners divided counties into townships with two elected justices of the peace each. Even judges, previously appointed by the state legislature to life terms, became elective and their terms limited to eight years. These changes replaced the aristocratic antebellum political order with democratic government in each county. This was a most welcome change to westerners long determined to have more say in state and especially local politics.42

Dismayed at the proposed constitutional changes under discussion, state Conservatives called their own assembly on February 5 and 6. Dubbing themselves the “Constitutional Union Party,” the Conservatives met to nominate candidates and to establish a platform. Disorganized and disappointed by their failure to stop the constitutional convention, the Conservatives tried to make clear their loyalty to the U.S. government. They professed devotion to the federal constitution but argued that Congress went too far with the Reconstruction Acts. In terms of the coming state election in April, the Conservatives determined that the great issue confronting North Carolina voters was race. Buncombe County native and former Confederate governor Zebulon Vance urged his fellow Conservatives to declare war upon the Republicans in the coming canvass. Black suffrage meant racial equality, in their eyes, and that was but a short step to complete racial domination by the state’s African Americans. Vance called upon Conservatives to prevent such a fate. By making race the central issue of the campaign, Vance and his colleagues seized upon an issue that they believed would unite the disparate elements of their own party while also luring lower-class whites away from the new democratic constitution and the Republicans. Such rhetoric and electoral appeals marked a strategic shift away from the politics of loyalty to the politics of white supremacy.43

Political anxiety, food scarcity, and charged racial rhetoric formed a volatile environment capable of exploding as winter gave way to spring. It did just that in Macon County on March 12, 1868. Federal troops from Morganton had accompanied a revenue collector into George Hawley’s subdistrict, where they seized a barrel of spirits and an illicit distillery around Cowee in northeastern Macon County. On their way to the Jackson County seat of Webster that night, a group of vigilantes approached the military encampment. The enemy wanted the confiscated goods back, and determined to take them. Orders to keep their distance failed to stop the distillers, and shots rang out in the night. A full-blown firefight erupted as the local band and the U.S. soldiers exchanged more than a hundred shots. When the mountaineers made “their escape to save their lives,” the sole casualty appeared to have been a horse and the confiscated property.44

It is fitting that the conflict over whiskey distillation and the federal revenue tax involved the Freedmen’s Bureau in western North Carolina. As the most prominent and accessible representatives of the federal government throughout the mountain region, bureau agents physically embodied the national government’s power and policies in many mountaineers’ minds. Because they were so closely associated with federal power, the Freedmen’s Bureau agents became active players and targets for moonshiners and other disgruntled highlanders resentful of the expansive postwar government. Moonshiners rallied in opposition to the Internal Revenue Bureau because they viewed it as an unwelcome extension of the federal government’s power at the expense of local autonomy. Such attitudes meshed easily with local white Conservatives’ views of the Freedmen’s Bureau, which combined opposition to one governmental organization easily with that toward another. Hawley’s part in reporting and dealing with the fallout of the violent clash between distillers and revenuers reinforced the view of the Freedmen’s Bureau as a dangerous outside organization in the minds of some mountaineers.45

Revenue agents certainly had their hands full, but unlike the Freedmen’s Bureau agents, they did not have to worry about distillation’s broader ramifications. Illicit distillers’ consumption of vital food resources in the northwest troubled agent James Carle, who replaced Allison in Wilkes County on February 29, 1868. On March 21, Carle reported that residents of his subdistrict showed a “flagrant disregard of all law and Military orders ... in regard to the distillation of liquors.” At least five stills were “in constant operation” within four miles of Wilkesboro, while in the rural sections of his district illegal stills were “shockingly numerous.” Breaking them up fell upon the revenuers and military, but Carle wrestled with the hunger caused by the distillers’ use of corn. Distillation consumed so much corn that Carle viewed it as the primary cause of poor people’s suffering. Still, Carle was unsure about how he could stop it. He did not believe he had authority to confront the moonshiners, whom he described as “desperate characters,” and he expected little aid from the civil government. If no aid came, he seemed ready to act on his own. Sources reported some one hundred stands of arms were available, and “there are Union men here and men who served in the Union army” who Carle felt “might be organized for that purpose.”46

Further proof of Carle’s discontent with his perceived lack of authority in dealing with moonshiners comes from his near-simultaneous letter to W. B. Royall, who commanded the military post in Morganton. Carle recognized the limits of the bureau’s authority, but matters worsened at such an alarming rate that only “prompt and decisive action” could “prevent almost instant starvation.” Wilkes County alone possessed anywhere between twenty-five and sixty illegal distilling operations—the exact number was unknown because of the location of the stills in well-hidden mountain locales. Informants also told Carle that the assessor informed distillers that the laws affecting them were a farce and that he would not interfere with them. This issue merged lawlessness, relief, and federal authority into one complex package for Carle. He lacked immediate authority on this issue, but he felt “it my duty to disclose to proper authority any outrage or threatened calamity to the people that seem to be ignored by those who properly have charge of the matter.” Empowered with the oversight of local authorities and responsible for helping southerners recover from the war, Carle brought distillation into his sphere of influence out of necessity.47

Carle’s fears became reality. To Samuel Wiley, U.S. revenue collector in Salisbury, he wrote that distilling had reached a level where prompt action was necessary to avert starvation. Yet Carle also stated that the issue evolved beyond simple distillation. Local Conservatives had politicized the issue and turned it against the federal government and the Republicans. Most moonshiners, Carle estimated, would stop simply if asked, but “designing men” used the distiller to oppose the government. On April 17, he reported that “from various reports and evidences of destitution now existing with the extremely poor in the three counties under my charge” that he needed money to help provide relief. In Wilkesboro, Carle resisted classifying the situation as a crisis since “extreme want” was “not yet prevalent.” But if current conditions persisted, local affairs demanded some remedy before the upcoming harvest.48

Issues of race, relief, and home rule collided as William W. Holden again came before North Carolina’s voters for governor in April 1868. For Conservatives, the gubernatorial election and the referendum on the new state constitution posed extreme challenges. The new constitution was largely the work of Republicans, including many black and northern-born representatives of that party. Holden represented something even worse in the state Republican Party and the sort of bad men Conservatives associated with it. With some white former Confederates disfranchised and local blacks registered to vote for the first time, Conservatives were less than optimistic. A general excitement surrounded the election, but Cornelia Henry of Hominy Creek worried that “the Radicals will beat us on negro equality.” She hoped, like many Conservatives in Buncombe County, “for the white man’s party” but feared “it will be voted down by the negroes and their equals.”49

From this desperation came the Ku Klux Klan, which Eastmond feared might spark a full-blown race war. The Buncombe-based agent first became acquainted with the Klan as a result of the whiskey tax. A federal revenue collector reported a threat posted on his hotel room door in Haywood County, but revenuers were not the only targets. Black mountaineers, whose economic autonomy affronted white control, such as a carpenter in Haywood County, also received warnings. A few days later, similar warnings appeared in Asheville. One of Eastmond’s African American servants encountered masked “boys” in Asheville on their way home from a meeting, and his office sign was torn down. Buncombe’s black population was not going to wait as the Klan likely planned its offensive. Local blacks armed themselves for “mutual protection” and never appeared in public without their guns.50

Because the Klan permeated the Conservative-controlled courts and local law enforcement, Eastmond feared that nothing short of a strong military presence could prevent violence. In December 1867, the Asheville town council petitioned General Canby for permission to establish a local police force. Signed by leading Conservatives, the petition wanted to deputize “night watchmen” to maintain order. Federal officials scrutinized their request, recognizing it as a possible effort to arm local Conservatives in a pseudo–slave patrol to suppress black and white Republicans. When the military responded that any such force must possess a racial balance and suggested that Eastmond oversee its formation, the town council revoked the request. Their about-face convinced the bureau agent that the military alone could prevent bloodshed. The failure to organize a police force left local affairs in the hands of civil officials, “just such men as would probably join” the Ku Klux Klan Eastmond charged. Without the military, the Conservatives’ opponents would have no alternative other than to protect themselves.51

The Klan threat that Eastmond included in his April report emphasized the importance of the election. It alerted Klan members to strike “when darkness reigns.” With a local group of “Black” Republicans challenging their status, mountain Conservatives embraced the Klan out of a mounting sense of powerlessness and racial alarm. Racial rhetoric had gathered steam in state politics over the previous months. From the state capital, the Sentinel led the charge. A June 29, 1867, Sentinel article entitled “The White Man’s Party” warned the state’s black population that opposing “the respectable and honest white people whom they have known all their lives, in politics, or trades, or interest” would prompt “counter action to the same extent.” Sentinel editor Josiah Turner Jr. also warned white voters that their failure to register and to vote would result in a white man’s party and a black man’s party. Turner put the onus for Conservatives’ increasingly threatening position upon black shoulders. By October, the Sentinel advised Conservatives to “instruct” black voters to avoid secret organizations like the Union League and to oppose a “Black Man’s party.” Clinging to antebellum paternalistic attitudes, Turner argued that only one in one hundred black men was ready for the responsibilities of citizenship. For that reason, the paper denounced the Republican Party as the single greatest obstacle to successful Reconstruction. That party “has filled the minds of the blacks with ambitious expectations and hopes, which are not intended to be gratified, only as a means of the elevation of the white Radicals.”52

Much of the impetus for the Sentinel’s bombastic opposition to the Republicans stemmed from observations in central and eastern North Carolina, but Conservatives employed similar political rhetoric in the mountains. A meeting of Conservatives in Rutherfordton brought Zeb Vance and thousands of his white allies to Rutherford County. One Conservative speaker after another blasted the Republicans over the course of several hours. Burke County Conservative Burgess S. Gaither gave “one of the most directly forcible arguments in denunciation of Radicalism and negroism.” Vance was the main attraction, however, and not even a severe storm could stop his thundering address. Mocking Republicans in attendance, Vance imagined a scene where an African American militia captain led local Republican leaders George W. Logan and Ceburne Harris in drill, made comical by Vance’s exaggerated impersonation of the fictitious black officer. Over three hours, Vance “brought home” to his listeners the need to defend their white skins. He urged them to oppose the integration of the militia, to denounce social equality as black supremacy, and to save their children from the indignity of integrated schools. Vance rarely disappointed his listeners when on the stump, and Rutherfordton Western Vindicator editor Randolph A. Shotwell believed that “he excelled himself” on this occasion. So effective was Vance, the Raleigh Daily Sentinel boasted, that several Republican attendees renounced their party and “cursed the men who led them into it.”53

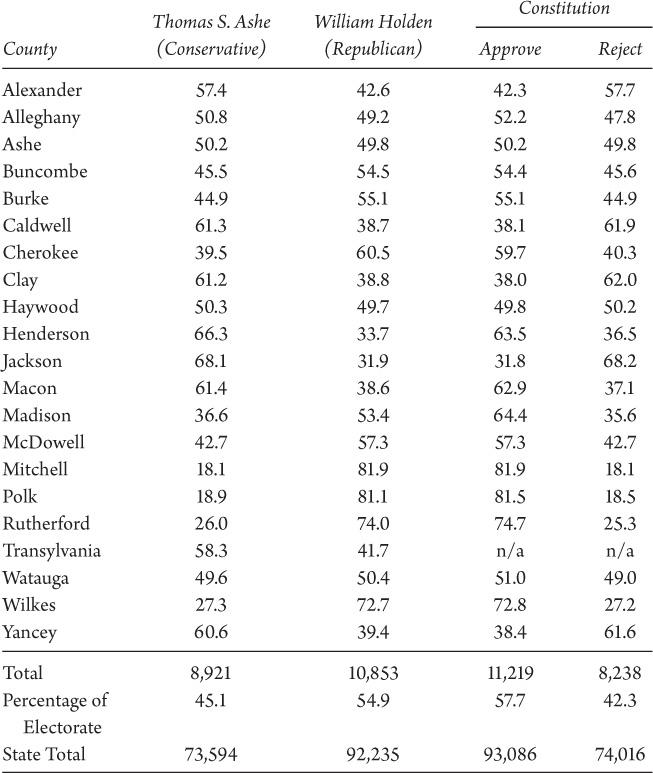

Despite their bombast, the Conservatives failed to defeat the Republicans in April. Holden captured 92,235 or 55.6 percent of the votes for governor statewide, which included a 54.9 percent majority in the western counties. Meanwhile, the constitution coasted to an even more decisive victory. It garnered a 55.7 percent affirmative majority and over 11,000 or 57.7 percent of the vote in the west. The results proved that the Conservatives’ racial strategy failed to boost voter participation and instead helped ensure Republican victory. Western North Carolina witnessed a high voter turnout—over nineteen thousand of the roughly twenty-four thousand registered voters cast a ballot in the election. What is more interesting, however, is the role of black western North Carolinians in the Republicans’ success. Although there is no way of knowing exactly how African American highlanders voted, it is not hard to see that they played a critical part in the Republican victory when one notes that party’s margin of victory in Buncombe, Burke, and Watauga Counties. In most western counties, the difference between winning and losing was minuscule (see Table 3). African American voters represented an invaluable swing vote. For example, Holden won Buncombe County by fewer than two hundred votes. If less than half of the 418 registered black voters in that county voted Republican, they carried Holden to victory. Even in counties where black people were a distinct minority, they still held great political potential. Watauga County had only thirty-six registered black voters, but white residents proved so divided that Holden won the county by a slim five votes. Given the enthusiasm among southern blacks for the party of Lincoln and the aid granted by mountain bureau agents, it seems likely that black voters were instrumental in both Holden’s and the constitution’s success.54

TABLE 3 Gubernatorial and Constitutional Election Results in Western North Carolina Counties, 1868

Source: Connor, North Carolina Manual, 1001–2, 1016–18. County results expressed as percentages for each candidate and ratification of the Constitution.

Republican victories had a double-edged effect on North Carolina. The election of a Republican governor—and a Republican-controlled legislature—marked a significant shift in local and state power. White and black Republicans rejoiced at their victory and looked forward hopefully. Their twin victories also convinced national policymakers that Congressional Reconstruction had succeeded. Holden took office on July 4, 1868. In the wake of his inauguration, the Freedmen’s Bureau agents in the west received orders from the state commissioner to close their offices. Effective January 1, 1869, each office in the mountain counties would close permanently. State bureau assistant commissioner Jacob Chur relieved Hawley from duty in August and instructed him to sell what bureau property he had in his possession and travel to Goldsboro. “Use as much dispatch as you can in breaking up,” Chur advised. Hannibal Norton and Oscar Eastmond received orders dismissing their clerks “with a view to reduce the expenses of the Bureau and in anticipation of its discontinuance in this State at no very distant day.”55

Events on the ground in western North Carolina revealed that the Republicans’ victory failed to remove the mountain counties’ need for the bureau’s services. When they received their orders to scale back or discontinue their operations, the western agents were still actively engaged in education and relief efforts. Some 250 students, Macon County agent George Hawley estimated, awaited the opening of schools throughout his subdistrict. As he compiled data and explored his command, he determined a need for eight schools. In order to meet that demand, he initiated a correspondence with the bureau’s superintendent of education and tried to drum up local support. African Americans in his district likely nodded along with Hawley’s assertion of the benefits of education at his meeting in Franklin, but their ability to support that school financially was another matter. Hawley speculated that the black residents of his district could potentially pay for a teacher, but his confidence in that matter was fragile. Politics acted as another significant obstacle. Despite “favorable” local support, Hawley noted in his June report that “Conservative politicians in the late commons opposed public schools, on various pretexts, the principal one being expense.” Before his arrival, they had already moved to abolish public schools to avoid sharing that privilege with black North Carolinians. That opposition crippled efforts in Hawley’s southwestern district, where few residents had money to spare, Hawley discovered, or “can afford their children the advantages of a school.”56

By August 1868, Hawley took heart in the progress made. A day school opened near Franklin under the direction of John C. Love, and a Sabbath school tended to the needs of freedpeople in Macon County. Still, the agent posited that 150 students spread throughout Clay, Cherokee, and Jackson Counties lacked adequate schools. Freedpeople could possibly board a teacher, but Hawley’s final report showed his frustration. Local blacks and the agent had worked to open a school, and there appeared to be no open opposition to the effort, but indifference could be equally damaging in the overwhelmingly white counties within Hawley’s district. Hawley reported that while no overt acts had taken place against education efforts, “neither had there been the slightest effort by the so-called leading men to establish schools for either poor whites or freedmen.” For that reason, he argued that the bureau must continue seeking northern charitable support for education “until the poorer class of people recover from the prostration produced by the war.”57

Wilkes County represented a success story in terms of African American education in western North Carolina. By the fall of 1868, James Carle reported five schools—three day and two Sabbath—in his district. All but one of those schools, it should be noted, were in Wilkes County. He wished to open two more but found that “interest does not seem favorable to the education” of freedpeople and poor whites. That was not true of the black population, whom he described in August as showing “all the zeal and interest that is manifested here in the cause of education.” Myrna Stokes and Osborne Hackett taught in Wilkesboro, and Henry Calvard taught a school in Lenoir, the county seat of neighboring Caldwell County. But the drop in the number of schools from five to three in November may have stirred some concern. In his final answer to the November questionnaire that asked how long outside charitable aid was needed to assist education, Carle recorded “the end of that time, if schools are to be successfully maintained, does not appear in present view.”58

The larger number of freedpeople in Buncombe and Burke Counties amplified the bureau’s power and accentuated its role in constructing a biracial Republican Party there. Sections of the South with greater black populations received greater relief money and educational support than the mountain counties, since greater numbers mandated greater support. Where Hawley was in the southwestern counties, indifference could greatly restrain African American institutions because they lacked the resources to overcome that disadvantage. It was easier to make strides in counties with larger black populations. In the coastal town of New Bern, black education efforts began during the war and commanded tremendous attention and resources as a result of the large number of African Americans living there. The American Missionary Association’s 1865 annual report, for instance, listed a single evening school in New Bern as having fifteen teachers and 175 students. An April 1867 Freedmen’s Bureau report listed one self-supporting school in Morganton with sixteen students and two such schools in Asheville serving eighty-one students. Early in the summer of 1868, just over one hundred pupils attended a new school that opened in Asheville. But as Asheville’s needs began to rival those in New Bern, financial difficulties threatened everything. Oscar Eastmond felt sure that success would continue if two teachers were employed there. At present, the bulk of the instructive duties fell upon a northern woman, Mary Reynolds, who worked for the rate of fifty cents per student. Economic concerns also threatened this school. Reynolds rarely received more than ten cents from each student. The dearth of funds threatened to close the school down, a disaster that Eastmond implored his superiors to avert.59

Between March and June 1868, Oscar Eastmond charted a slow advance in freedpeople’s education in his subdistrict. With two schools open in Asheville, he hoped to create one in Hendersonville, Waynesville, Marshall, and Brevard and another in Asheville. And while he noted that people in his subdistrict wanted free schools for all residents, Eastmond deemed it “about an impossibility” to draw any support from the black population. Between April and May, however, a new day school opened in Asheville, giving the Buncombe County seat two day schools and one Sabbath school. Two African American teachers, J. J. Reynolds and Edward Horsey, the same black Union League member assaulted by two boys for trying to get water to his farm, also joined the teaching ranks in Asheville. Eastmond reported a modest expansion with the opening of James A. Zachary’s school in Haywood County. By June he counted four schools, three in Asheville and one in Waynesville, but Madison, Henderson, and Transylvania Counties still had no schools.60

Compared to the efforts of Hannibal D. Norton in Morganton, Eastmond’s efforts appear modest. Norton took an active interest in education through the spring and fall of 1868. During March, he held an education meeting at the freedmen’s schoolhouse, and he visited the Morganton day school twice. Norton’s proactive efforts garnered him a more detailed understanding of the needs within his command, which he determined to be three schools within Burke County and one in McDowell County. Achieving these goals would be an uphill climb. While he recognized a need for these other schools to serve an estimated 245 students, local white support was not forthcoming. Where Eastmond found some support for education efforts in his subdistrict, Norton encountered sentiment “adverse to the education of Freedmen and Poor Whites.” Efforts to draw support from local white sources and the state government were “without success.”61

One reason for this opposition was undoubtedly the success already achieved by African Americans in Burke County. The Freedmen’s Bureau already owned a schoolhouse in Morganton that served 275 pupils, whose parents paid the teacher’s salary. By the fall, the freedpeople’s pecuniary support grew. In September, Norton reported four schools in operation, one of which was in Little Silver Creek in a building owned by the African American community itself. In November, Norton visited the day school four times and the Sabbath school twice. He also held two meetings at the “Howard” schoolhouse in Morganton. By the fall, the freedpeople’s financial prospects had worsened and they had but little for their schools. Their enthusiasm for education, however, kept the agent active in his mission. When asked how long additional aid from the bureau and northern charities would be necessary, Norton answered, “For two or three years at least.” Local successes made such commitment seem necessary and just.62

The Raleigh poet who read “North Carolina Free” spoke of promise. “The past is past,” the poem went; “the future shines.” At last, “the years of blood” seemed behind them with “smiling years of peace” ahead. An alliance between the bureau and local Republicans helped reshape the landscape in western North Carolina. Schools received federal support through the bureau, and mountaineers found relief through the bureau as well. Whites received most of this aid, which fostered closer ties between lower-class mountain whites and the federal government. Agents’ desire to prevent starvation and suffering led them into the growing conflict between distillers and the Revenue Bureau. Perhaps most importantly, the bureau oversaw the registration of new voters—including black highlanders—who delivered the critical Republican victories in the spring of 1868. Those victories inspired hope among the Republicans’ local constituents that the past was behind them and that the future would bring even greater gains, but the Conservatives had not had their share of blood. Backed into a corner by their failures in 1868, the Conservatives intensified their racial rhetoric, seized upon the unpopular whiskey tax to political advantage, and mobilized a violent new organization—the Ku Klux Klan—determined to topple this new regime in their region and state at all cost.63