Chapter Six: The Beginning of a “New” Mountain South

Agriculture, Railroads, and Social Change, 1872–1880

Wilkes County had little to offer William Horton Bower, an ambitious and well-connected young man, in 1873. The postwar years had not been prosperous ones for western North Carolinians. Currency dried up, debts threatened families’ farms, and the state’s railroads teetered on bankruptcy. Searching for opportunity, Bower sought the guidance of Augustus S. Merrimon, the Buncombe County judge who had lost the 1872 gubernatorial election only to be named a U.S. senator the following year. Merrimon endeavored to keep the young man at home, even if it made his advice somewhat disingenuous. “I doubt very much the wisdom of leaving North Carolina,” Merrimon advised. Things looked bleak, but Merrimon trusted that “we have a soil, climate and advantages that capital and labor will take advantage of” once “the misrule which has cursed and crushed us so long” succumbed “to wise counsel and the peremptory demands of society for wholesome government.” Patience was one resource mountaineers could ill afford to exhaust. “You are in the right section of the State, if you can afford to come on gradually & not despise small things” because “there is more for young men of talent and moral excellence in any of our Western Counties.”1

Beneath Merrimon’s optimistic advice was some “Do as I say, not as I do” hypocrisy. Confronted with similar straits in 1867, Merrimon opted to resign his mountain judgeship in favor of a legal practice in the state capital. At that time, he viewed western North Carolina as a dead end. Six years later, one must wonder whether Senator Merrimon recognized the irony in instructing somebody not to follow in his footsteps. For all the wrangling and second-guessing, Merrimon lost the young man to the romance of the West. William Horton Bower chose California and a teaching career over waiting—and hoping—for his native section to recover.2

Regardless of Bower’s decision, Merrimon mapped out a vision for the future shared by many of his fellow Conservatives—including those in the mountains. A “new” South appeared on the horizon, one that capitalized on the soil, climate, and resources that Merrimon praised in his missive to Bower. Labor and capital would develop those resources, but equally important was the end of what Conservatives decried as Republican misrule. The two aims were inseparable for men like Merrimon. In order to move the state forward, to extract the natural resources of western North Carolina, to complete the long-stalled railroads, and to restore good government, the biracial Republican regime that captured the state government in 1868 had to fall. The middle-class white urban Republicans of the mountain counties did not repudiate their previous African American allies; rather, they deemphasized divisive issues such as civil rights in order to achieve long-frustrated hopes for the region’s internal improvement. Ku Klux Klan assaults and intimidation began the process, and a market-oriented New South would finish it.3

Western North Carolina lagged behind neighboring mountain regions in several important ways. Both southwest Virginia and East Tennessee had railroads and had expanded market production prior to the Civil War. The end of slavery, however, meant that western North Carolinians’ quest for internal improvements now aligned more neatly with the economic interest of both the state and the South at large. Efforts to remake and develop the Appalachian region in the 1870s linked postwar political issues with the emerging economic issues of the New South. Between 1872 and 1880, western North Carolina went through one of the most important—and underappreciated—periods in its history. The region’s relationship to the broader market economy changed as local leaders pushed for modifications in its agricultural and manufacturing base. Mountain boosters pursued railroads with a passion, but they also hoped to develop the region’s livestock, minerals, and other natural resources into market commodities. Although they achieved measured success with those enterprises, it was the rapid investment in tobacco that accelerated the region’s development and facilitated the ultimate arrival of railroads linking them to the national market economy.4

For much of the postwar period, mountaineers battled one another for control over local affairs. Conservatives emerged from the Civil War bloodied, but still strong enough to regain power. Unionists and Republicans aligned with local African Americans and outside forces to swing the pendulum in their favor, but when the federal government pulled back, Conservatives employed violence and intimidation to cow white and black Republicans in the early 1870s. Once back in power, the elite white mountaineers who dominated the Conservative Party reinstated the antebellum domination of local politics by elites. But it was not really a restoration of the old elite, because middle-class professionals now led the way. Having never fully rejected outside authority, they hoped to integrate the region into the national market, embracing outside investors and foreign capital to develop the region’s natural resources and build its railroads without threatening their local control. Because such boosters were often town dwellers as well, they promoted their hometowns aggressively. In western North Carolina, no town rivaled Asheville in economic and political importance. Its advancement gave focus to the postwar movement for improvement while also threatening to divide the region as friction developed between the Asheville faction and the surrounding counties.5

Like the antebellum period, the rhetoric of progress emphasized the issue of internal improvements. Roads and railroads were obsessions for many western North Carolinians, especially middle-class, town-based whites who stood to profit from the region’s integration into the national market. During the antebellum period, popular support for turnpikes, roads, and other such projects proved so strong that no politician, regardless of party, dared to oppose them. Even as construction in other sections of the South slowed by the 1850s, mountaineers built roads like the Hickory Nut Gap Turnpike linking Asheville and Rutherfordton. While roads linked the western-most counties with markets in Virginia, South Carolina, and Georgia, state boosters promoted the concept of an east–west railroad to keep mountain products within the state. North Carolina’s state government largely focused on projects in the east and central parts of the state, however, so mountaineers hunted help elsewhere. South Carolinians hoping to link Charleston by rail with the markets of the Ohio Valley proposed a rail line through the North Carolina mountains in 1835. Local boosters had similar ideas for routes following the Tennessee River, but none possessed the allure of the Western North Carolina Railroad (WNCRR), binding eastern and western North Carolina through an extension of the North Carolina Railroad. The state finally adopted a charter for the WNCRR in 1855. Not only did it provide for a railroad to Asheville; the charter included two branch lines to Paint Rock and Ducktown on the Tennessee state line as well. It must have seemed cruelly ironic to many mountain residents that their long-desired railroad had barely crossed into Burke County when the war halted its construction in May 1861.6

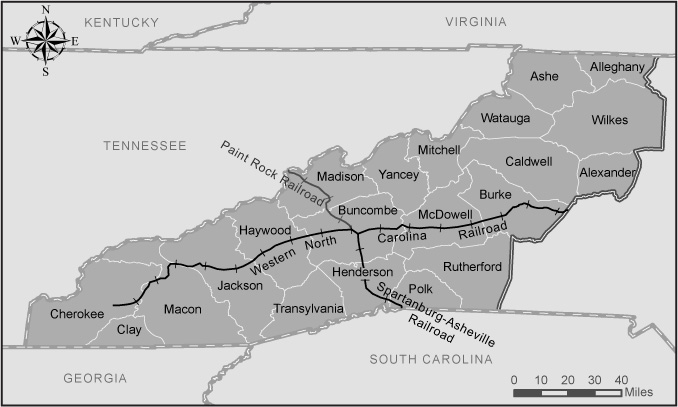

In the fiercely partisan years that followed the war, politics plagued the WNCRR. Governor Jonathan Worth preferred to staff the company with political allies, which necessitated the removal of Unionist and future Republican Tod R. Caldwell and the restoration of Samuel McDowell Tate, both from Burke County, as a director in 1866. For Republicans attempting to forge a political party out of white and black southerners, the “gospel of prosperity” embodied by the “iron horse” was even more important because it drew whites into the party despite their uneasiness with its biracial makeup. The North Carolina Republican Party’s platform pledged vigorous state aid for railroad construction in 1868, and new governor William Holden and his legislative supporters moved swiftly to aid the WNCRR that spring. On August 14, 1868, the legislature revised the railroad’s charter to create independent Eastern and Western Divisions of the company in order to accelerate the western road’s construction. The Eastern Division ran from Salisbury to the French Broad River, while the task of crossing the Blue Ridge and extending the road to Paint Rock and Ducktown belonged to the Western Division, which organized its own directors at a meeting in Morganton in October 1868 (see Map 3). They selected as their president George W. Swepson, a prominent central North Carolina businessman.7

MAP 3. Western North Carolina Railroads, 1870s–1890s. Map produced by Andrew Joyner, Department of Geosciences, East Tennessee State University.

By year’s end, frustration and confusion supplanted the optimism of the summer. In 1869, track stopped at the mountain’s edge in Old Fort in McDowell County because of mismanagement and fraud rather than geography. When the WNCRR’s Western Division was created, its directors set about raising two-thirds of the stock required by the road. On October 20, 1868, Swepson presented a certificate to Governor William W. Holden claiming to have $2 million in subscriptions from reputable sources. Such subscriptions contributed to the Western Division’s capital stock, and Swepson informed the governor that 5 percent of that stock had been paid. These purchases triggered the release of four thousand special tax bonds worth $4 million. No one knew it at the time, but the railroad’s president had neither the necessary money nor subscribers. Later testimony indicated that about $300,000 was raised at the Western Division’s organization, but no more than maybe $400 of that counted toward the 5 percent required by law.8

The Western Division scandal represented a nightmare for embattled Republicans. Up to this point they had been denounced as “bad men,” illegitimate because of their reliance on outside power to control local politics, and subsequently the target of political violence in an attempt to silence them. Charges of corruption added to the pressures facing mountain Republicans in the early part of the decade. As the people of North Carolina realized the extent of the crime perpetrated against them, former Western Division president George W. Swepson came under intense criticism as did his northern Republican partner, Milton S. Littlefield. The scuttling of a major state-financed railroad project by a northern Republican and a Conservative North Carolina businessman hastened the Republicans’ declining power within the region and the state. Fair or not, the anger over the WNCRR’s collapse fell heaviest upon Governor Holden and his fellow Republicans. On December 1, 1870, a public meeting in Asheville gave voice to the frustration stemming from the scandal. The assembled mountain residents felt the sting of the railroad setbacks more deeply than any other event since the Civil War. They appealed to the state legislature to do anything to bring Swepson, Littlefield, and their co-conspirators to justice.9

The railroad scandal also added to a gradual drift—though not an outright break—between white and black mountain Republicans. African American voters remained a central component of the party’s statewide strategy, but the previous commitment to blacks’ civil rights expressed by white mountain Republicans appeared to wane. Governor Caldwell, himself a mountain Republican, ran for reelection in 1872. Despite the partisan impeachment of his predecessor William W. Holden, Caldwell boldly proclaimed his commitment to black North Carolinians’ rights. In a letter to the Grant and Caldwell Club of Raleigh, the governor expressed his commitment to “zealously guard, and to the best of my ability defend, the rights and liberties, civil & political, of every citizen of North Carolina without distinction of race, color, previous condition, or present political creed.” But he also attempted to reach out to the all-important white voters by distancing himself from federal proscriptions on former Confederates’ voting rights. As a mountain Republican, Caldwell knew all too well the importance that moderate whites could play in an election.10

To central and eastern audiences with large African American voting populations, such expressions were vital to the Republicans’ success. Meanwhile in Caldwell’s native Burke County, one of his closest political allies spun a slightly different tale. Caldwell confidante W. A. Collett kept his friend abreast of local political matters and their party’s prospects through the 1872 campaign. On June 9, Collett warned the governor that they might “have some trouble with the Negroes.” To be clear, Collett did not dread black voters’ defection to the Conservatives. He feared that African Americans expected rewards for their Republican loyalty. As he informed Caldwell, Conservatives had “put it in their [African Americans’] heads that they ought to have a fair proportion of the offices.” This concern was not new. In 1867, an African American Republican named Alfred Stokes fired up a Wilkes County crowd by suggesting that black Republicans should have a more prominent role in office holding. In 1872, the mountain Republicans faced a crossroads. Their promises to their black neighbors were not empty rhetoric. But times had changed. The Freedmen’s Bureau and army were gone, leaving mountain Republicans without direct access to federal power. Klan raids had shaken their ranks. Now Conservatives threatened their governmental control—even at the vital county level. Mountain Republicans struggled to find a way to contain black political ambitions while preserving their party loyalty. Collett proposed to nominate them for the local school committee and magistrates, safe in the belief that African Americans would not vote for the Conservative candidate.11

The idea of placating African American highlanders with nominations for the school committee was calculating but not entirely dismissive. It was demeaning because it showed a racist determination not to share power in a meaningful way with African Americans at the local level. But the idea was also practical in that Collett and other mountain whites knew the passion that black citizens had for education. Despite the heightened concern regarding railroad development, education constituted an internal improvement of tremendous importance to black highlanders. In the decade after emancipation, African Americans threw themselves into the creation of schools throughout the region. Freedmen’s Bureau agents, when they were in the region, aided this effort. Government reports throughout 1867 and 1868 counted the dozens of schools opened from the northwestern to southwestern corners of the region. Even the local Conservative press took note of their achievements. The North Carolina Citizen praised the well-disciplined and well-trained students at a local school supervised by the African American Episcopal Church. Its editors described the school as “a matter every good citizen should feel an interest in—the negro constitutes a very large and important element in our social and political government, and the more he can be elevated, educated, and morally and religiously educated, the better citizen he becomes, the more valuable in all respects will be his status.” However, success in education could not fully overcome developing tensions.12

Whites’ obsession with railroads left black mountain Republicans’ needs on the political periphery. A palpable sense of desperation, particularly west of the Blue Ridge, sparked an outcry as news spread that Governor Caldwell opposed a possible sale of the Eastern Division of the WNCRR. Republicans and Conservatives alike decried the idea. White mountaineers crossed party lines in support of internal improvements, building class-based coalitions without the taint of federal interference or racial divisions. In late 1872, Pinckney Rollins wrote Caldwell that “it is the universal desire of all parties West of the Blue Ridge that you withdraw your objections to the sale of the WNCRR ... as we believe this is the only chance for a RR in this part of the state for all time to come.” Asheville petitioners called on the governor to sell the railroad to the Southern Security Company, which would then pay the road’s debts and finish its construction, because the town’s economic future hung in the balance. The writers plaintively moaned that “this road is our only hope for any early outlet to the world.”13

Over the next several months, white men from Asheville bombarded the governor with appeals to drop his objection to the sale. Republican superior court clerk J. E. Reed informed Caldwell that the people resented his “interference” in the sale. Great wrongs had befallen the state in the name of the WNCRR to be sure, Reed added in consolation, but only through a sale might the road’s completion be soon realized. On January 17, 1873, Robert B. Johnston informed his brother, state senator Thomas D. Johnston, that the people of Asheville “are all in favor of the sale of the [Eastern Division] thinking it to be the only chance for the completion of the road.” Because of the amount of stock owned by men east of the Blue Ridge, including Caldwell’s own home county of Burke, Johnston warned his brother that legislation may need to decide the matter. If the governor succeeded in putting the sale upon the legislators’ shoulders, then Buncombe County residents expected Thomas Johnston and his colleagues to both sell the road and secure its completion within four years. Asheville-based lawyer Calvin M. McLoud added that he had “never seen a people so unanimous on any subject” as they were on the Eastern Division’s sale. Dry goods dealer James P. Sawyer put his advice to Johnston in verse:

Strike till the last armed foe expires,

Strike for your altar & your fires,

Strike for your mountains & spires,

The Rail Road through your native land.

“Go for the Road like hell & fear not,” Sawyer added; “otherwise tremble for your days as a representative are numbered.”14

For all the Ashevillians’ bluster, the Democrat-controlled legislature balked at the sale. Theodore F. Davidson could hardly believe it. The Asheville lawyer considered the sale’s failure as “one more hope for our people blasted.” “Is it possible that we will be compelled to live surrounded on all sides,” he cried, “almost in hearing of the Whistles-by railroads with all their advantages, in the old wooden way?” With railroads snaking their way through southwestern Virginia, East Tennessee, and upstate South Carolina, Davidson recognized that his region—and his town—was at a disadvantage. Davidson considered such regional competition fatal because western North Carolina was already “half a century behind in the means of success.”15

Republicans from the western side of the Blue Ridge accused comrades like Caldwell from its eastern side of betrayal. A Conservative in Shufordville noted that Buncombe County Republicans had turned upon the governor. The sticking point was Asheville’s future. From the west side of the ridge, a railroad to Asheville transcended all other issues. Transmontane Republicans like Virgil Lusk, W. W. Rollins, J. E. Reed, and others challenged the governor. Rollins bypassed Caldwell and appealed instead to a Conservative state senator for assistance. He advised Thomas Johnston, a fellow Ashevillian, to do all that he could for the road’s sale. “I trust that our people will see that it is to the interest of the whole state,” he wrote, “to have our road completed at once.” In June 1873, Thomas D. Carter informed Governor Caldwell that in his opinion “the people west of the French Broad river, and in fact, to the people of this entire section, this is a question of transcendent importance—paramount to politics, or almost anything else, and the people as a whole are fully alive to its importance.”16

Under immense pressure from all political sides, Caldwell came to an apparently satisfactory solution: consolidation. His longtime Morganton neighbor Burgess S. Gaither told the governor that he supported the legislature’s plan to recombine the Eastern and Western Divisions into the Western North Carolina Railroad Company. It did not matter to the Conservative Gaither that this scheme enriched Caldwell’s political fortunes. Gaither had become frustrated with his own party, particularly outspoken editor Josiah Turner Jr., who Gaither believed had exaggerated the amount of tunneling left to complete as two miles instead of a quarter mile and reported that the stockholders would receive fifty cents on the dollar for their private stock. Such charges had “done the work for him in Western North Carolina,” Gaither told the governor. Gaither professed “a great contempt for [Turner] & cannot be forced by party obligations to sustain him.” Of course, Turner’s acting like “a lunatic entirely unfit to have the control of a paper” and the Republicans’ declining power in his region made such cooperation more palatable. Still, Tod Caldwell’s untimely death on July 11, 1874, jeopardized the compromise.17

Though the WNCRR’s fate remained uncertain, support for railroads increasingly mirrored antebellum efforts to build internal improvements in that it cut across party lines. Republicans and Democrats supported state aid for the railroad’s completion to Asheville. In June 1875, Governor Curtis H. Brogden received numerous letters avowing the mountain counties’ support for the WNCRR. A Republican, Marcus Erwin, took pride that a member of his party held such popularity that “the people of all parties in the extreme West look to you as willing & able to meet & manage the heavy responsibilities imposed upon you by the legislature of the last General Assembly.” Jackson County Democrat James R. Love agreed, though without the Republican pride. “The great interest the people of the West feel and manifest on all occasions, irrespective of party, in the building and early completion of the Western NCRR” was palpable, according to Love. After the state purchased the road, according to a law passed that month, Love urged the governor to employ convicts on the railroad to achieve the ultimate link of the rail to the Tennessee line. Once the line reached Knoxville, then it could achieve links with Louisville, Cincinnati, and the markets of the Mississippi Valley.18

Party lines fell before the might of festering interregional rivalries. Southwestern mountaineers, still committed to the Ducktown extension of the road, felt slighted by the Asheville clique favoring the French Broad extension to the Tennessee state line. Macon County state senator James L. Robinson warned Brogden not to slight the far western counties. In language eerily reminiscent of that directed at “rings” and Republicans earlier in the decade, Robinson charged that the “French Broad men have had almost absolute control of the Western Div. WNCRR & yet they have done nothing but fritter away what little money they have secured from the wreck.” Tread carefully, Robinson warned Brogden, because the people were “very sensitive on this matter” and they already “felt slighted” by the portion of the governor’s annual message devoted to the railroad. Failure to heed the needs of Robinson’s constituents could derail the entire project. Everyone in western North Carolina wanted the railroad, but neglect of the southwest in favor of the “French Broad men” invoked passions that could tear the region apart. Robinson concluded with the observation that the fate of the WNCRR “has more in it to concern the white men of the country than questions of finance or almost Civil Rights.”19

Republicans further struggled to balance the labor needs of their beloved railroad and the biracial makeup of their party. It was a balancing act upon which they increasingly sided with improvement. The WNCRR needed capital, it needed broad state support, and it needed labor. For many mountain Republicans, the ability to construct their railroad with African American convict labor trumped all else. Native son Zebulon Vance made the WNCRR a priority after he captured the governorship in 1876. In his inaugural address, he called for all unassigned convict laborers to be sent to work on the WNCRR in McDowell County. By 1878, 558 convicts were at work in horrible and dangerous conditions. Between December 1877 and February 1878, the convicts worked eighty-eight out of ninety days despite harsh winter weather and a meager state allowance of $0.30 per man for support. Of the 537 convicts working on the road in 1879, 75 died in accidents. Landmarks that would come to define the mountain route, like the Swannanoa Tunnel, proved especially treacherous. On March 13, 1879, twenty convicts lost their lives when part of the tunnel collapsed. All told, at least 125 men lost their lives struggling to finish the road.20

Even if the issues of race and railroads were unable to destroy the mountain Republicans, the equally divisive issue of taxation threatened to overwhelm them. Struggling to maintain a coalition of moderate white professionals, African Americans, former Unionists, and lower-class white farmers, the Republicans fumbled the issue of taxation—specifically the tax on whiskey in the 1870s. As Conservatives denounced Republican racial policies and railroad corruption, they also began appealing to the largely rural, lower-class whites who distilled corn and fruit into illicit spirits as an economic supplement to farming. Conservatives hailed distilling as a natural right and denounced the Republicans’ ties to the federal Bureau of Internal Revenue. Henderson County Republican Hamilton Ewart blamed the whiskey tax for Republicans’ electoral defeats in 1876. The western people’s animosity “against the Internal revenue law, and the hatred and contempt entertained by the people for its execution” severely damaged the party in the mountains. Following a clash with a revenue collector, a McDowell County Republican griped “that his own party had turned against him.”21

Republicans faced a no-win situation with the liquor tax. Since the war’s end, mountain Republicans had become dependent on federal patronage to hold power in their home region. The Bureau of Internal Revenue provided them with three hundred patronage jobs. Following the Klan backlash, such direct links to the federal government were vital to mountain Republicans’ political survival. And they took notice. Leading Republican Alexander H. Jones introduced a measure in Congress to exempt taxes on fruit brandy, a popular economic side project of many Henderson County residents. Although such measures earned approval among some of his constituents, the fortunes of the Republicans dimmed. Despite growing differences, they managed to retain the governorship in 1872.22

But by the mid-1870s, even onetime allies like Oscar Eastmond became anathema to many mountaineers. In June 1873, the former Freedmen’s Bureau agent was a U.S. commissioner aiding the Internal Revenue Bureau in western North Carolina. Eastmond became embroiled in a controversy involving W. A. Smith, the receiver for the WNCRR. As part of federal revenue laws, official bonds of office had to have a revenue stamp. Eastmond accompanied U.S. marshal and deputy revenue collector W. H. Deaver from Marion to Morganton, finding so few revenue stamps that Eastmond concluded that “one Hundred Thousand Dollars would not cover the fraud that has been committed upon the Revenue in this respect.” In Morganton, Deaver inquired whether Smith’s railroad bonds had the requisite stamp. When Smith refused to allow Deaver to inspect the bonds, Eastmond issued a warrant for Smith’s arrest. Perhaps Smith acted to protect himself or prominent citizens by retaking the bonds. Maybe he acted to force a public showdown with Republican tax collectors for political gain. Regardless of his reasons, Eastmond heard Smith’s case and found him guilty of obstructing a federal official in his duty. Not to be outdone, Smith swore an oath against Eastmond and Deaver that led to their arrest later that night. It was a brazen challenge to federal authority, Eastmond claimed, and he fully expected federal district judge Robert Dick and other Republicans to rally to their aid.23

Instead, Dick reprimanded Eastmond for abusing his authority. Dick had appointed Smith receiver for the WNCRR, which meant that Smith held the bonds on behalf of the court. Thus Dick ordered all of the parties to appear before him to explain their actions in August. For their part, Dick ordered Deaver and Eastmond to answer charges of contempt for interfering with the court’s appointed receiver. Both federal officials faced removal from office if found guilty of misconduct. Chastened and perhaps concerned that he no longer held the favor of the court, Eastmond tendered his resignation on November 14, 1873.24

With Republicans on the ropes, state Conservatives moved to consolidate their control through a new constitutional convention. Voters rejected this idea in 1871, but Conservatives pushed it through in 1875. A central part of this effort was the alteration of county government. Under the Republican-crafted 1868 constitution, county officials became elective for the first time in the state’s history. In western North Carolina and other regions with strong Republican organizations, this allowed that party to capture a number of influential local positions. The convention restored “full power by statute to modify, change, or abrogate” existing county governments to the Conservative-dominated state legislature. This Conservative-led “reform” promised to restrict local democracy and revive the antebellum aristocratic order at the county level. Such amendments played a key part in the 1876 gubernatorial campaign between Zebulon Vance and Republican Thomas Settle, whose party fought gamely—though ultimately hopelessly—against them. County government reverted to the old system in February 1877, and the Republicans’ power throughout the state waned.25

According to the North Carolina Citizen, there was more at stake than who occupied the governor’s chair. For sure, Conservatives craved a victory to recapture an office that had eluded them in 1872. But the Conservatives’ 1876 gubernatorial victory also represented something of a deal between the eastern and western wings of that party. “In the campaign of 1876 the people of the East fought for white supremacy,” the editors wrote, while “in the West the white people governed themselves, but had no railroads—they were told to give their Brethren of the East relief and they should have their greatly needed roads.” The Citizen’s editors expressed limits to the Conservatives’ platform of retrenchment and reform when their region’s vital economic interests were threatened. “Let not the real interests of the state be made to suffer by the cry [of retrenchment],” they warned, “but whenever an expense can be curtailed or wholly abolished without damage to the true interests of the State, let it be done.” For proponents of an east–west rail route through the state and its proposed extensions linking North Carolina to the markets of the Ohio and Mississippi Valleys, there was no more vital interest than the WNCRR’s completion. To eastern and central North Carolinians standing against further expenditures on the road, the Citizen warned them against continued demagoguery about retrenchment and budget cutting simply to create a positive public image.26

For many white southerners, railroads offered the promise of industrial development; for mountaineers, railroad construction went hand-in-hand with the realization of western North Carolina’s agricultural and natural potential. Adequate transportation networks were necessary to bring capital in and haul foodstuffs, raw materials, and other goods out. But not all development-minded mountaineers emphasized the products of the land. Some men looked to the land itself. The Philadelphia-based Western North Carolina Land Company advertised 128,000 acres of “good land, well watered, heavily timbered, more accessible and cheaper than Western lands” for sale in Caldwell, Henderson, McDowell, Mitchell, Watauga, Wilkes, and Yancey Counties. Wealthy landowners gobbled up thousands of acres with an eye on the future extraction of valuable mineral and timber resources. The aptly named T. C. Land wrote the president of the North Carolina Central Railroad of the advantages of extending his road from Statesville, North Carolina, to the East Tennessee and Virginia Railroad in November 1866. He noted the presence of abundant timber along the proposed route, with only Warrior Creek and the Yadkin River standing in the way. A veritable garden of untapped riches would make the effort well worth it. Land spoke glowingly of the mountains’ crops “produced cheaper and in greater abundance and of better quality” as well as its “many mines of Gold, Silver, Copper, Lead, Iron, &c which are said to be as rich as any in the known world.” The proposed route would pass near Elk Knob in Ashe County, “(said to be) the richest Copper mine in the US.” Minerals, timber, and produce plus “Cattle, Hogs, Sheep, &c [which] can be raised here without number” made western North Carolina a speculator’s paradise.27

Outside investors recognized the potential riches both above and beneath the surface in the southwestern corner of the state. Prior to the Civil War, D. D. Davies supervised work on several copper mines in Jackson County. Once the war was over, prospective buyers sent Richard Owen, a natural science professor at Indiana State University, to evaluate the region’s potential. Owen came to western North Carolina in the late 1860s believing “that the lands were unproductive, or, at least, that fertility was the exception and was confined to the valleys.” Once he was there, however, the region surprised him. Corn grown on the rugged hillsides impressed Owen, who termed it equal to that produced in the alluvial valley lands. He was ambivalent to the higher-elevation wheat, but the oats were “excellent,” the rye “peculiarly good,” and the Irish potatoes “as fine as I ever saw anywhere.” In addition, Owen praised the orchards, especially the apple trees, and the grazing pastures, which he deemed “the most attractive feature in this farming district.” Amid his explorations, Owen saw cattle, sheep, and other animals grazing and in “remarkably good condition.”28

Near Whiteside Mountain in the Cashiers Valley, the professor found favorable prospects for miners. He also determined that the Maddron mine in Haywood County was “promising” after preliminary work revealed the presence of copper, silver, and emery. Owen also detected an abundance of nigrine, “a titanic mineral employed in painting on porcelain, and for giving the requisite color to artificial teeth.” For capitalists looking for more to smile about, Owen reported that “excellent” iron could be made from the magnetic iron ore. Horse Cove and the Cashiers Valley stood out as the best option for men seeking their fortune in gold. Industrialists capable of developing the gold deposits with crushers might be able to trace the gold to its “quartz matrix” in the vicinity of Whiteside Mountain. Copper mines were available in Macon and Jackson Counties as well. It was a region, Owen concluded, with great possibilities.29

Local speculators drummed up interest in the southwestern part of the state. D. D. Davies, who had begun work on the Jackson County lands before the Civil War, sought investors and buyers in 1873. He traveled from New York to Pittsburgh with disappointing results. Still, his optimism survived these setbacks. “I have got half of Jackson Co. on the market & must succeed in something,” he wrote in late February. But selling those properties was an uphill battle, if not an insurmountable mountain. Another land agent, Ovide Dupré, met with prominent dealers in New York City without success. That spring Dupré regretted that “there seems to be but little disposition among the capitalists of N.Y. to invest in Southern Real Estate.” It seems the risks still outweighed the potential rewards. The frustrations shared by such speculators and land agents seeking quick sales of potentially lucrative mines did little to quell the excitement in the southwestern counties, whose residents perceived mining as a path to prosperity. According to R. V. Welch, who updated Thomas Johnston on the southwestern counties’ prospects in late July, there remained “much excitement in Jackson about mica copper &c & several parties are now at work.” Erstwhile efforts by determined individuals sustained hope for future profits from old speculative investments.30

Later in the decade, the southwestern counties saw considerable progress in their extractive industries. The Asheville-based North Carolina Citizen noted that “mica-mining has been profitable in the past two seasons.” A market for mica had developed in Macon County. Franklin-based merchant A. S. Bryson supposedly paid roughly $50,000 in cash for mica, which could be used as an insulator in stoves and other devices. By August there was “more bustle and animation” in Macon County than Albert Siler had ever seen. “We have quite a number of strangers with us,” Siler wrote his wife, “some to enjoy our summer climate” while others came as part of the “perfect furor in regard to mica.” Northern agents crowded Franklin buying mica at $1.50 to $4.00 per pound. Over four months later, Macon County touted several mines. The “Rocky Face” mine atop Cowee Mountain and the Allman Mine produced “handsomely,” while investors discovered a promising vein in the Hall Mine. For mountaineers who had suffered with a down economy for over a decade, the success of these mines was welcomed warmly. The sale of the Jenks Corundum Mine garnered special attention in the North Carolina Citizen, which predicted confidently that the venture, allegedly paying $200 to $300 a week in wages, might increase its workers’ pay some five to ten times in the coming year. Already twenty thousand tons of corundum had been extracted in four weeks.31

Few individuals invested as heavily in western North Carolina’s mineral prospects as Calvin J. Cowles of Wilkes County. The former Unionist and merchant dedicated himself to the development of his Gap Creek Mine roughly fifteen miles from the Virginia and Tennessee borders in Ashe County. Cowles purchased the mine with four partners in 1856, but he bought out each partner until he eventually became the sole proprietor in 1866. Gap Creek became Cowles’s leading economic concern. Twice prior to the Civil War, he hired mineralogists to evaluate the mine. Those experts deemed the mine’s copper deposits to be excellent, and one of them also noted a moderate amount of gold and silver. For his part, Cowles judged the mineral vein (which was between two and fourteen inches thick), the natural drainage of the property, and the nearby access to waterpower as its strengths. Still, the venture faltered because of the lack of a nearby railroad—the nearest connections were roughly fifty miles away—and Cowles’s own lack of cash.32

To entice northern and foreign investors, Cowles contracted geologists James and Cummings Cherry to assess the property in late 1870. The brothers found a raw mine. Little work had been done to extract the ores. A few test holes exposed some quartz, but water and debris complicated efforts to examine at least one subterranean shaft. While the Cherrys may not have shared Cowles’s lofty expectations, they found enough gold, iron, nickel, and especially copper to dub Gap Creek “quite promising.” They declined “promising positively a valuable return to a mining company who would operate the mine.” Instead, the geologists recommended a moderate “outlay as will be necessary to expose the vein at a depth below the surface where its ores are concentrated and diffused evenly throughout the matrix and their nature and value can be definitely ascertained.” According to that plan, development could be had for less than $3,000.33

Neither was the Cherrys’ proposal out of step with Cowles’s own thoughts. Cowles offered to let investors operate it for a year without paying him a cent until profits were realized, but that plan produced little more than frustration. Potential northern and British investors came and went. Cowles clung to his faith in the mine’s profitability, even as the capital necessary to make it productive failed to materialize. A Philadelphia businessman nearly bought into Gap Creek in 1877, but he could not muster the requisite funds. Boston capitalists also inspected the mine that year without purchasing it. Finally, Cowles found an investor in 1880. Northern-born William C. Brandreth of New York City invested and helped Cowles form the Copper Knob Mining Company, which consolidated the Gap Creek property into a single company with several of Brandreth’s other mountain mining enterprises.34

Capitalizing on the region’s resources also occupied Walter W. Lenoir’s attention. One of three surviving brothers of the influential Lenoir family of Caldwell County, Walter seized upon the war’s end to invest heavily in land. His brother, William, left vast amounts of land to him and his siblings, which Walter purchased from the various heirs amid postwar uncertainty. Secure in the deeds, Walter moved from one end of the region to the next mapping out his new holdings, settling with squatters, and subdividing the lands into smaller, more marketable lots. Throughout 1868 he continued surveying his Watauga lands, even managing to sell some of the tracts—albeit to family members who fretting for Walter’s solvency grudgingly purchased parcels of his land. His wealthy merchant brother-in-law, James Gwyn, agreed to subtract $2,000 from the sum Walter owed him in exchange for a Beech Creek parcel with a possible silver vein. Walter’s brother, Rufus Lenoir, wanted nothing more than to focus on the old family home of Fort Defiance in Caldwell County, but he also agreed to buy four hundred acres along Boone Fork in Watauga County. Walter had loftier goals than pity sales to his family. In 1870, he listed his “Crab Orchard” in Haywood County with a land company. Again, he broke much of his vast holdings into smaller units for sale, but like the Watauga transactions, Walter found that his customers were familiar faces: cash-strapped local farmers and concerned loved ones.35

For all his speculation, Lenoir’s true love was farming. He devoted significant time, energy, and resources to promoting agriculture in the Carolina mountains. The Lenoir family presents a revealing view into post–Civil War husbandry in western North Carolina. Thomas Lenoir’s three sons owned property in Caldwell, Watauga, and Haywood Counties, and factoring in their brother-in-law, James Gwyn, they also had a significant presence in Wilkes County. While Rufus and Thomas farmed for a living, Walter found his “greatest pleasure” in dealing with animals and crops, and, as he put it, “not merely in eating them.”36 Improving and managing his land became something of an obsession with Lenoir. Convinced that his Haywood County Crab Orchard’s best chance at profitability rested with livestock, he dutifully set about converting it into a first-rate stock farm. Getting his property into a position to make money was no small task, given the region’s stagnant economy in the years immediately after the war. Walter understood this as well as anyone. In February 1868, he commiserated with his brother Rufus over the scarcity of currency. Dramatic drops in the price of cotton, Lenoir noted, had a ripple effect that “to a very great extent cut off the best market for the bacon & live stock which are the principal products of this part of the country.” Matters might get worse before they got better, but Lenoir dug in his heels and vowed to see his beloved mountains through. Somewhat tongue-in-cheek, he confessed his determination to “stand it ... as long as the yankees can.”37

Farmers in Caldwell County experienced a relatively stable decade in the 1870s; other families throughout western North Carolina were less fortunate. Caldwell County farmers experienced a growth of a tenth of an acre in the average farm size, despite the creation of 141 new farms. The county’s livestock, however, dropped 25.6 percent in value. Most mountain counties experienced only modest changes in average farm size. Both Rutherford and McDowell County suffered the highest average farm size decline of roughly 35 percent, while Alleghany County farms expanded by 16.6 percent. Fluctuations in the value of livestock convey the mountaineers’ struggle to find a marketable commodity. Only two counties, Henderson and Macon, suffered a harsher decline than Caldwell County. Livestock declined in value more than $90,000 in each of those two counties (38.3 and 33.8 percent, respectively). Meanwhile, other counties saw a veritable explosion in livestock values. Perhaps Walter Lenoir’s neighbors in Watauga County heeded his advice. Their livestock increased in worth by more than 25 percent. William R. Love’s investment in sheep contributed to a massive expansion of livestock in Jackson County, which saw an overall increase of more than $1.29 million invested in livestock—a 689 percent jump. Such extremes overshadow the more modest fluctuations experienced by the region as a whole.38

Lenoir’s vision for mountain agriculture led him to pursue new people for the region as well as new knowledge. He wrote the editor of the Germantown Telegraph recruiting emigrants from eastern Pennsylvania. It was a logical move. In March 1860, a Pennsylvanian appealed to the state legislature to devote three thousand acres in the Carolina mountains to experiment with merino sheep. Since roughly 1820, farmers around Philadelphia practiced an interconnected cycle of production combining orchards, pasture, timberland, and improved acreage into a rural ecology of complementary parts. Livestock roamed the land, feeding on its produce and then fertilizing the land with their recycled manure. When merino sheep first arrived in the United States, they set off something of a mania as northern farmers imported the Spanish animal and sold their wool to nearby mills. The Pennsylvanian believed that the western counties could become the leading wool-producing section of the world if they committed resources to it. Civil war and sectional hatred drove those ideas from mind before Lenoir looked to Pennsylvania again. “I have believed, ever since the war that there would be a new movement of Pennsylvania farmers to Central and Western North Carolina,” Lenoir wrote, “as soon as they could understand how welcome they would be, and how well they could do for themselves.” In other words, Pennsylvania farmers practiced a mixed form of agriculture that might profit in western North Carolina while furthering that region’s integration into the national market economy.39

North Carolina had settled down, finally, from the turmoil of war. Lenoir tied the agricultural future of the region to the political success of the Conservatives. Secure in their state’s redemption after the Klan’s reign of terror and William Holden’s impeachment, the Conservatives still did not control the governorship—until 1876. In what became known as the “Battle of Giants,” Conservative Zebulon B. Vance soundly defeated Republican Thomas Settle, capturing more than 60 percent of the mountain vote. Settle and the Republicans’ dramatic defeat allowed Lenoir to present a calm, stable image to the Germantown editor. Leading Conservatives, many of whom were from western North Carolina, endorsed Lenoir’s quest for Pennsylvania emigrants. Governor-elect Vance, his brother Congressman Robert B. Vance, and U.S. senator Augustus S. Merrimon supported Lenoir’s plan. Lenoir offered assurance: “The sentiments I express are their own sentiments, and they know them to be the sentiments of the people among whose leaders they are now, as they were during the war.” Northern settlers had nothing to fear. Although the “Battle of Giants” was a highly partisan contest, Lenoir also dubbed it “probably the most peaceful election that has ever taken place ... in this very peaceful and law abiding state.” The only way further tension might remain over the controversial presidential election was if northern settlers brought “a Tilden army and a Hayes army ... from the North to fight on Southern soil.”40

Nearly a year after reaching out to Pennsylvania farmers, Lenoir wrote a long, almost boisterous letter extolling the mountain region’s virtues to D. D. Ludlow, of Dunkirk, New York, who also contemplated a move to western North Carolina. Lenoir sent Ludlow an unabashed piece of boosterism, something akin to a state of the region address. His purpose was clear: recruit more northern farmers. In particular, Lenoir targeted northern farmers who could overlook western North Carolina’s poor transportation system and transition smoothly into the region. Lenoir lauded the bounties of the mountain landscape. Cash crops could be found in tobacco, flax, and hemp, but those crops were not his focus. Staple crop agriculture was not the vision Walter had for his prospective emigrants. Instead, he proposed a mixed form of agriculture that blended a traditional reliance on corn, wheat, rye, and buckwheat with an emphasis on livestock production. “Probably our principal agricultural wealth,” Lenoir instructed Ludlow, “will always be in our meadows and pastures and our live stock & their products.” The mountain grasses and climate led to finer, heartier sheep and cattle. Combining that agricultural capacity with a railroad would transform western North Carolina into “a large part of the vegetable market” for the growing cities of the United States.41

Lenoir promoted the region through a form of agriculture that promised long-term stability at the expense of short-term profitability. Pennsylvania farming occupied the minds of other regional boosters. An October 1878 edition of the Blue Ridge Blade pointed its Morganton readers toward the Keystone State’s success with wheat as another path to success for western North Carolina. Duplicating Pennsylvania’s success required more than planting more wheat; it necessitated a greater knowledge of and utilization of manure. “As a general thing,” the paper instructed its readers, “it is well understood that manure must be liberally applied to induce a good crop.” Mountain farmers mistakenly plowed the crop under, but it took time for the wheat’s roots to develop to the point that it benefited from the manure. Applying ample portions of manure to recently planted wheat facilitated the absorption of the dung’s minerals and facilitated an early start to its roots’ growth. If more farmers applied this technique to their wheat, western North Carolina might develop an additional crop to complement the livestock and earn its farmers further profits.42

The hunt for the highlands’ agricultural panacea was an uneven venture. Some mountaineers sought their fortunes in livestock, following Lenoir’s vision for the region because one needed dung-producers if they were to employ closed-circuit agriculture like that practiced in Pennsylvania. Colonel W. R. Love of Jackson County partnered with the American Mining and Manufacturing Company to purchase 150,000 acres for grazing, manufacturing, and mining in the spring of 1867. Love and his partners planned to carry twenty thousand sheep on the land as well. Another ambitious individual planned to open a sheep farm on South Mountain, just south of Morganton in Burke County. He was able to move one or two sheep to South Mountain for about $70 each. Two sheep scarcely made a major investment, but the following year he planned to acquire an additional 1,000 to 1,500. Nothing would be left to chance. Besides the imported sheep, the investor hired a Scottish shepherd to tend to his flock. Everyone he conferred with agreed that sheep were a “good investment if managed,” and although he expected no immediate profits, with an investment of $1,000 or more, he predicted that he would succeed quite admirably within two or three years.43

Regional boosters promoted the mountain counties as ideal for various money-producing animals. One potential migrant, Dillwyn Parker of West Chester, Pennsylvania, had narrowed down his investment choices to Colorado, Texas, and western North Carolina in early 1878. During the latter part of the nineteenth century, Colorado and Texas gained national recognition for their cattle. One of Parker’s friends who had moved to North Carolina informed him that the Carolina highlands were perfect for such an enterprise. Also, the mountain counties offered cheap land for as little as $1 and as much as $10 an acre. Recognizing the region’s potential, the North Carolina Citizen ran a piece in the November 7, 1878, edition ranking sheep for farmers to raise. The key, the paper claimed, was to select the sheep with the heaviest fleeces and greatest yield of meat. Not quite a year later, the paper cited the Charleston News and Courier in support of the “new departure” investment in sheep, particularly Saxon sheep because of their softer and higher-quality wool.44

Embracing livestock as the future of the region had the benefit of a strong connection with its past. Mountain farmers had long depended on livestock for food, labor, and sale. Sheep represented a wrinkle in that tradition, one that was familiar but not as prominent as many hoped it might become. Newspapers endorsed it, investors bought into it, and the legislature debated ways to protect it. Still, sheep never really took off as a market commodity. Agricultural census figures reveal modest fluctuations throughout the region between 1860 and 1880, nothing that suggests a radical increase in mountaineers’ investment in sheep. Madison County experienced the largest increase, from 5,760 in 1860 to 10,269, but even that growth is unremarkable. In the end, livestock stayed a valuable secondary commodity.45

Where Walter Lenoir viewed mountain agriculture as an integrated system—crop, livestock, fruit, timber—less patient individuals looked for a single commodity upon which to make their mark. Agriculture in the Carolina mountains changed dramatically in the 1870s, not because of sheep, but because of tobacco. Just over a year after the war, Calvin Cowles reported that Wilkes County farmers had cultivated twice as much tobacco as they had the year before. Walter Lenoir’s brother-in-law, James Gwyn, turned to tobacco as “about the only crop we can raise here now to pay.” A Civil War veteran from Henry County, Virginia, Samuel C. Shelton, planted bright leaf tobacco on three acres outside of Asheville in Chunn’s Cove with great success in 1869. Several enterprising farmers followed Shelton’s lead. The Asheville-based Western Expositor reported in early 1875 that “the experiments for several years past has shown that several of the counties in Western North Carolina are peculiarly adapted to the growth of fine leaf tobacco.” Success in Buncombe, Madison, McDowell, Burke, and Caldwell Counties reverberated through the entire region. It accelerated Asheville’s growth and regional importance as an economic center, and it furthered the region’s integration into a national market system. As the Western Expositor noted, western Carolina tobacco commanded the highest price at the influential Danville and Richmond tobacco markets. For his part, Shelton became something of an international sensation—and an undisputed local hero—in less than a decade. At the Vienna Exposition in 1873, Shelton’s Madison-grown chewing and smoking tobacco won first premiums. Local boosters anticipated a repeat performance at an impending Paris Exposition.46

The success of tobacco offered a new direction for mountain agriculture, the Western Expositor argued, that moved the region more toward the market-oriented economics of the New South. Its editors heralded tobacco as “the great money staple of the Western portion of the State” and urged mountain farmers “to go earnestly to work.” Boldly, the paper predicted great economic wealth—to the tune of $500,000 annually—in Madison, Buncombe, McDowell, Burke, Caldwell, and other mountain counties in as little as five years. Tobacco also served as a catalyst to economic change for highland boosters. If the farmers followed their advice, the editors foresaw the addition of “such an amount of money to the country that manufactories of all kinds would spring up throughout ... affording employment to all the laborers of these localities.” In 1875, tobacco cultivation meant profits, manufacturing growth, and jobs.47

The final years of the decade saw escalating support for tobacco, predominantly in the Buncombe County press. Echoing the Western Expositor, the North Carolina Citizen hailed the expansion of tobacco production in the final years of the 1870s. Rather suddenly Asheville had become an important and integrated part of the southern economy, competing successfully with established tobacco markets like Lynchburg and Danville. Even when the tobacco crop struggled during the summer of 1878 and national tobacco prices fell to levels last seen twenty-five years earlier, mountain tobacco continued to draw high prices. According to the Citizen, its prospects were high enough to sustain the optimism of Republicans like W. W. Rollins. With unrestrained pride, the Citizen chirped that even in down times Buncombe tobacco “butts the bull off the bridge,” an allusion to their Durham-based Duke rivals, and that “glorious little Madison will stand in the front ranks.” When a merchant in Galveston, Texas, received and examined a local product, he immediately ordered more. Together, these counties’ tobacco proved of such fine quality that they were “running other tobaccos from the market.”48

It is not entirely clear what part African Americans played in the region’s tobacco boom, but there are some clues. An 1883 Asheville city directory listed ten African Americans as working in the city’s tobacco industry. Nine of them worked as tobacco stemmers, a task typically reserved for African American women throughout the southern tobacco industry. Towns like Asheville established new bonds with the surrounding countryside as bright tobacco created new market connections, town-based jobs, and services. But the connection and role of black farmers to the tobacco industry are unclear. One historian estimates only 19 percent of the African Americans listed as farmers or farm laborers in 1880 owned their own land. The remaining 81 percent, it stands to reason, worked as day laborers, tenant farmers, or sharecroppers. Given the profits to be gained from tobacco in the latter half of the 1870s, it seems that landowners likely devoted more of their land to tobacco than in previous decades.49

A survey of tobacco growers in Buncombe, Madison, and Haywood Counties, however, suggests that African Americans were not a significant part of the tobacco boom in the fields. In those three counties—which led the way in regional tobacco production in the 1870s—1,679 farmers planted the staple. Of the 665 Buncombe County growers, only 321 hired labor. The largest producer in the county, Robert Thadeus Coleman, produced eight thousand pounds on seventeen acres. Although the census statistics do not tell how an employer allocated his or her labor, the fact that Coleman hired white laborers for 150 weeks and black workers for 108 weeks suggests that both performed some labor related to his tobacco interest. Still, Coleman appears to be more an exception than a rule. Only seventy-one, or 10.7 percent, of Buncombe County tobacco producers hired any black workers. Madison County had 846 tobacco growers in 1879, yet only 8.5 percent of them hired African Americans. Leading Republicans W. W. Rollins and G. W. Gahagan grew 12,000 and 3,200 pounds of tobacco, respectively, but only the former hired black workers. Rollins employed whites for 100 weeks and blacks for 52 weeks. Gahagan paid $400 for 100 weeks of white labor. The county’s largest grower, J. M. Smith, brought in 15,000 pounds without a single paid black worker. He contracted 120 weeks of white labor for his farm. Haywood County ranked a distant third with 168 tobacco growers, paced by Henry L. Kingsmore with 5,000 pounds grown on nine acres. But all of Kingsmore’s tobacco was brought in without a single paid African American worker. Kingsmore paid $500 for 125 weeks of white work. Only seven Haywood County producers hired black hands.50

Agriculture and tobacco had become front-page news in Asheville for good reason. The weed had spread rapidly. In April 1879, a Yancey County correspondent from Bald Creek reported “the tobacco fever is very high” and that “a goodly number” of farmers prepared to join the ranks of converts. By year’s end, excellent specimens raised in Cherokee County gave hope that tobacco might succeed there as well. In August 1879, construction began on the Asheville Tobacco Warehouse, embraced by the Citizen as “one of the most important enterprises” in the town’s history. Local dreams of Asheville becoming an economic center for more than just the mountain region appeared to be coming true. Finally, the newspaper cried, tobacco could be grown, sold, and manufactured in the Buncombe County seat. Asheville’s economic destiny—not to mention the promoters wedded to the town—was at hand. Small local manufacturing establishments evolved into more “respectable” enterprises with even greater growth on the horizon. The region had found a commodity that gave the town and region greater economic resonance within national and international markets. By year’s end, discussions were already under way for more tobacco factories to open in Asheville the following spring.51

Tobacco’s success brought the issue of the region’s economic development and Asheville’s prominence into sharper relief. An article in the Citizen heralded “Asheville’s Opportunities” on September 11, 1879. Already a popular tourist destination, the paper promised that the town’s future was “as a business center for some sixteen or twenty of the very best counties of the State.” Northern and southern investors had taken great interest in the town’s commercial potential, but in order to achieve its full height, the Citizen urged its readers to do more “to give the town that permanent basis of wealth and growth so essential to the building up of a large city.” In short, Asheville needed manufacturing and not just of tobacco. Woolen mills, like one already operating in Weaverville, “would be of great benefit” to Asheville and would connect the town with the surrounding region’s investment in sheep. Tobacco stood above the others as the crown jewel with its fine brands fetching from $0.40 to $4.00 per hundred and would soon be manufactured locally as well. “Buyers will only go where there are warehouses, and tobacco will go where there are buyers,” which the Citizen argued must be Asheville. The explosion of tobacco production, increasing from twenty-five thousand pounds to more than 1 million combined pounds per annum in Madison and Buncombe Counties, meant that “tobacco factories will ornament many of our city lots in less than five years.” It was also suggested that the rising number of cattle and sheep in the region promised the development of a thriving shoe manufacturing industry in Asheville. One such enterprise produced “the very best men’s and women’s shoes ... to the number of near or quite a hundred pairs per week.” More could be done, however, and boosters pushed hard for Asheville’s further development.52

The town-based boosters heralded tobacco’s success, but their hopes for a new-style town in Asheville brought their class bias into greater relief as well. Like Walter Lenoir, they wanted mountain farmers to change their ways; however, these boosters proved more aggressive in their critique of traditional agricultural methods. A scathing letter from “One-Horse Farmer” published in the Citizen on April 10, 1879, condemned mountain farmers for failing to keep up with modern farming trends. The author, who lived in Garden Creek in Haywood County, criticized farmers for being complacent. Too often mountain farmers sat around and discussed politics “like we could all live and grow fat on that style of business,” he argued in what may have also been a not-so-subtle jab at the lower-class whites who supported the Republican Party. “In my one horse-way of looking at things,” he opined, “the ordinary system of farming in Western Carolina is simply ridiculous, a disgrace to the enlightened age in which we live, and, what is worse, a crying sin against High Heaven.” If farmers would rotate their crops and fertilize their fields, he charged, they would achieve the greatest agricultural productivity in the world. Even tobacco farmers needed to manure their fields to maintain the soil’s productivity. For his part, “One-Horse Farmer” promised to practice what he preached; he vowed to gather one hundred loads of manure to ensure his corn’s success. When other farmers followed suit, western Carolina “will have a radical change for good in ten years.” By October, he offered to give the farmer who produced the most wheat per acre on a lot of two to five acres in 1880 a subscription to a “No. 1 agricultural journal.” It is fitting given his disdain for modest farmers’ practices that the reward amounted to nothing less than a total reeducation in tilling the land.53

Convinced that tobacco constituted “the most profitable crop our Western friends can raise” and that Asheville “is rapidly becoming a first class market for the sale and manufacture of tobacco,” the North Carolina Citizen gave noted tobacco grower Samuel C. Shelton his own column in November 1879. Locally raised tobacco ranked among the finest in the world, Shelton argued in his first installment, “but for the want of capital [it] could be placed in every town, village and hamlet in the United States.” Capturing the spirit of the times, Shelton proclaimed, “We want factories to spring up all around, and we want the vast wealth of this fertile and beautiful section to be developed and utilized at home, nor will we be satisfied until the sound of magnificent triumph shall reverberate along these grand mountains.”54

Shelton echoed “One-Horse Farmer” in his criticisms of mountain farmers. Less than a month after he published his first column, Shelton identified three classes of farmers. The first type believed that he knew everything and that there was nothing new for him to learn about working his land. It is telling that Shelton’s first archetype was the small farmer who produced first and foremost for his family. In the eyes of the market-oriented Shelton, these farmers “retard the progress of advancement by being unwilling that anything should progress beyond the limit of their own self-sufficiency and would proclaim anything a humbug that they did not invent.” Nothing could convince them that tobacco could be made profitably in the Carolina mountains because these farmers, according to Shelton, knew some distant acquaintance who allegedly lost everything after investing in the staple. The second class, the naïve farmers who blindly applied everything told to them, was equally detrimental because they put all their faith in hired help and employed any number of foolhardy schemes to get rich quick. Western Carolinians must aspire to be a third kind, to which Shelton ascribed “good sound judgment” and a recognition of their limits. Such humble farmers embraced new techniques and approaches with open minds. Shelton challenged his readers to “look at this mirror, and ‘see if you see yourself’ in either class.”55

Men like Samuel Shelton and newspapers like the North Carolina Citizen espoused a middle-class ideology that grew throughout the nineteenth century. During the antebellum period, this took the form of temperance and other reform movements. After the war, the issue shifted more toward internal improvements and urban development. Once local control became the province of the elite once more, members of the elite worked with all comers to open their region to outside capital and development. They rejoiced in recognition from outside investors and presses. Asheville’s growth in the 1870s impressed visiting news editors from South Carolina. One of those observers noted that Asheville was “rapidly improving” and predicted that once Asheville had its railroad connections, the town “will rival Atlanta in commercial importance.” When that visitor considered the town’s importance as an economic hub for nineteen counties and its appeal to tourists, he opined, “We would not be surprised if she outstrips the Gate City.” Buyers from across the country, even from across the world, would flood Asheville’s dusty streets in pursuit of their product. All that remained to get them there was the railroad, which sat well outside of town. The North Carolina Citizen predicted confidently that the railroad would reach Asheville by spring, and with the arrival of the “iron horse” would come tobacco buyers from Richmond, Durham, Lynchburg, New York, Brooklyn, Cincinnati, and Louisville.56

Critical to Asheville’s and the region’s tobacco and agricultural dreams was the completion of rail links within the North Carolina mountains. Like the WNCRR, the Spartanburg and Asheville Railroad had moved forward in fits and starts. In 1837, a convention composed of representatives from nine states concluded that the French Broad River valley offered the best route for a railroad connecting Charleston, South Carolina, to the West. Construction began on the so-called Blue Ridge Railroad, but financial setbacks, the loss of influential backers, and the Civil War halted progress. In September 1874, its supporters regrouped. At a great barbecue in Spartanburg, South Carolinians sought to rekindle efforts to build the road. Former Confederate treasury secretary Christopher G. Memminger fired up the crowd. Two gaps, a twenty-five-mile hole between Wolf’s Creek and Asheville and another seventy-five-mile break between the latter town and Spartanburg, remained in the original project. Memminger put the onus for building the road squarely on the shoulders of the people. “The greatest and most magnificent structure of the middle ages (St. Peter’s Church at Rome) was built by small contributions,” Memminger prodded; “let no man therefore say that his means are too small to allow him to contribute.” When finished, the road would connect the cotton South with the foodstuffs of the mountains and ultimately the major markets of Charleston and Chicago, hopefully, Memminger added, to the benefit of the former.57

To some degree, the Spartanburg and Asheville Railroad preyed upon existing intraregional rivalries. An Asheville booster wrote Curtis H. Brogden, who assumed the governor’s chair upon Caldwell’s death, asking for convicts to work on the Spartanburg and Asheville road. He made clear that his preference was for the convicts to work on the WNCRR, but because both were “Western Enterprises pointing to my town & through my County,” he supported both. If Asheville boosters preferred the WNCRR, mountaineers in the southern part of the region preferred the South Carolina route. Collett Leventhorpe, a British-born Confederate general who lived in Caldwell County, preferred the southern link with Spartanburg for strictly economic reasons. “State pride has nothing to do with the markets,” he noted ruefully, “and on the line of the NC Central there is no market for anything Rutherford [County] produces.” A southern route promised to connect Rutherford County with “a people who want & will buy everything you have.”58

While the road to Asheville stalled to the east, the railroad to the south made steady progress during the 1870s. The road’s president, David Robinson Duncan, tirelessly pushed construction ahead. Confronted by economic uncertainty in the spring of 1878, he went to Asheville and convinced two creditors to take first mortgage bonds on the road as payment. Duncan become so prominent that the Citizen believed that the people of western Carolina would “elect him to any office from governor down to a member of congress.” Hendersonville residents were even more enraptured. The people “were in buoyant spirits over the prospects of the iron horse snorting in their midst at an early day.” By the summer of 1878, the Spartanburg and Asheville road had pushed through Pace’s Gap at the border of Polk and Henderson Counties. Its next stop, Hendersonville, was a mere nine miles away.59

As the winter of 1878 yielded to the spring of 1879, optimism dwindled as the road faced foreclosure. The federal district court in Charlotte scheduled arguments regarding the mortgage and sale of the Spartanburg and Asheville Railroad. Unpaid contractors vowed to contest the sale, and western Carolinians retook the familiar position of battling for an endangered rail link. Buncombe County attorney James H. Merrimon received discretion to handle the county’s stock, but the Citizen affirmed that public opinion stood on the side of paying the contractors and resuming construction. The state legislature took up the matter, debating whether to aid the embattled road. Again, tensions flared between Asheville and the surrounding region. Buncombe’s senator, Theodore F. Davidson, argued that the bill threatened to deny the people of his county full return on their $100,000 subscription. As he was flush with anger, his mind entertained other explanations—including some rather far-fetched conspiracies. The railroad’s bondholders never intended to finish it to Asheville, he charged, preferring instead to halt at Hendersonville.60

No doubt the first train’s arrival in Hendersonville surprised some people on June 1, 1879. A celebration followed on July 4, 1879. State officials and railroad executives from North Carolina, South Carolina, and Tennessee and a crowd of four to six thousand, including as many as two hundred from Asheville, joined in the “general rejoicing over the fact that the railroad had at last crossed the mighty Blue Ridge and penetrated the great valley of the West.” Brass bands played triumphant tunes as the dignitaries and the happy onlookers enjoyed a day of speeches full of congratulations and optimistic future plans. North Carolina governor Thomas Jarvis, who earned “ringing and prolonged applause” for his part in the road’s construction, urged its extension to Paint Rock on the Tennessee state line, “which would place them in close connection with the outside world.” Yet, in spite of the celebration, not everyone was satisfied. The Asheville-based North Carolina Citizen noticed that as everyone predicted a steady march to the Tennessee line, no one spoke of a connection to Asheville. Frustration and confusion led the editors to end on a plaintive note, remarking that “although there was nothing on the face of last Friday’s demonstration looking to the prosecution of the work at an early day, we earnestly hope for good results from the day’s labors.”61

The fact was that a neighboring county seat had its rail connection and Asheville’s connection to both the Spartanburg and Asheville Railroad at Hendersonville and the WNCRR sat in developmental purgatory. In early 1877, the North Carolina state senate passed a railroad bill, which met, in one observer’s opinion, an oddly passive reception in Buncombe County. Thomas Johnston’s brother informed the senator that the leading figures of the French Broad Valley “do not seem as much alive on this question as I have been expecting to find them.” Instead, their silence espoused a “good index of the deep and abiding feeling that is taking hold of the thinking solid men of the Country.” At times, the bill’s fate appeared dicey, but Johnston wrote his younger sister proudly on February 19, 1877, announcing the bill’s passage. While the ultimate goal of completing the road to Asheville seemed no less closer to realization, Johnston felt that the convict labor and money granted the road would help bring a train to Asheville within the next two years. “I know this will appear to you to be a long time,” the weary state legislator sympathized with his sister, “but if we can get it by that time I shall be exceedingly glad.”62

Johnston’s prediction proved surprisingly accurate. Time and again, the state found a way to keep the WNCRR afloat. They bought it out of bankruptcy in 1875, and it lurched forward on the backs of taxpayers and a predominantly black convict labor force. Even then, however, the road remained in peril. In 1880, the WNCRR caught a break it hardly deserved. William J. Best, an Irish immigrant who made his money as an accountant to venture capitalists in New York, offered to purchase the embattled railroad. Best’s group of investors offered to assume the state’s stock in the embattled railroad and promised to finish the project. Frustrated in his efforts to complete the road as governor, now-senator Zebulon B. Vance greeted Best’s offer with enthusiasm. “Great Lord,” Vance exclaimed, “is there any danger to his getting away!”63

Best’s offer represented something akin to a pot of gold at the end of a rainbow previously anchored by fool’s gold. Vance’s successor, Governor Thomas J. Jarvis, wanted to free the state of the financial albatross that was the WNCRR, and he saw in the New York group an escape from further hardship. He took his case to the state legislature, and convinced the majority of the legislators to support the sale on March 20, 1880. True to form, the hoped-for easy end to this process eluded all involved. In late May, Best informed the governor that his investors had balked. The agreement required the northerners to complete the railroad not only to Asheville but also to Paint Rock by 1881 and to Ducktown by 1885. Best told Jarvis that such stipulations were too much for his backers. Jarvis blanched. This news threatened the road and his reelection campaign. All was not yet lost. Vance and Jarvis turned to Alexander Boyd Andrews, a former staffer of Vance’s and now the superintendent and vice president of the Richmond and Danville Railroad. Andrews had the reputation as a strong, capable railroad administrator, and they asked him to support Best’s plan. Behind closed doors, Jarvis pressured Andrews, whose road was about to be sold, and he got the Richmond and Danville Railroad’s backers to pay the WNCRR’s debt. The road was back on track.64