Chapter 4. What Can You Do Best?

At the beginning of the twenty-first century, psychologist Martin Seligman helped pioneer a new movement in the field of psychology, one that laid the tracks for the Blue Flame. To understand the importance of this new ideology, let’s rewind a bit:

A witty, well-educated New York native, Seligman began his psychology career studying learned helplessness in dogs—something that my lazy and emotionally needy rescue pup can surely identify with. Seligman began to reflect on how twentieth-century psychology seemed focused entirely on unwellness: on mental illness rather than well-being, on fixing what was broken.

In its early years, psychology had adopted the disease model of its more grown-up sister profession, medicine, and focused on investigating and classifying what is wrong with people in order to find ways to make them better. In essence, the goal was to help to make miserable people less miserable.

To give well-deserved credit, this disease model had a massive positive impact on mentally unwell populations. Of the sixteen most common classifications of disorders—such as depression and alcoholism—fourteen are now treatable, and two are curable.

The focus on diseased and debilitated people, however, overlooked a huge population of humans—the relatively untroubled ones—whom Seligman thought could greatly benefit from the field’s growing understanding of the human mind and behavior. Why, Seligman wondered, wasn’t psychology focused on helping these people to thrive, rather than just survive? Couldn’t this same understanding of human psychology that was used to help the unwell get better also be used to find interventions that could lead to happier, more fulfilling lives for the rest of us?

Seligman wrote, “Psychology should be able to help document what kinds of families result in children who

flourish

, what work settings support the greatest satisfaction among workers, what policies result in the strongest civil engagement, and how people’s lives can be most worth living.” This came from the January 2000 issue of

American Psychologist—

an issue that was devoted entirely to contributions from leading thinkers in this new field that went on to become known as

positive psychology

.

[10]

Seligman posited that psychology should be just as concerned with human strength as it should be with weakness. His own epiphany, as he tells it, came from an everyday conversation with his five-year old daughter, Nikki.

He was doing some weeding in his garden and confesses that he became irritated by young Nikki’s shenanigans as he was hard at work. She was dancing around, throwing weeds up in the air, and singing as her father toiled away. In a moment of reactivity, he had enough and hissed at his playful young daughter, as many of us would find ourselves doing in this situation.

Nikki walked off, chastened. A short time later, she came back to respond to her irritated and dismissive father.

“Daddy,” said Nikki, “do you remember the time before my fifth birthday? From the time I was three to the time I was five, I was a whiner. I whined every day. When I turned five, I decided not to whine anymore. That was the hardest thing I’ve ever done. And if I can stop whining, you can stop being such a grouch.”

Ouch. Well played, Nikki. Her insightful, yet crushing comment had the impact of a precision-guided Hellfire missile. Seligman says he had three waves of insight as a result of the devastating strike.

First, he realized that Nikki had stopped whining all by herself without any help from grumpy old dad. He recognized that kids can improve and grow without intervention from their parents. How cool.

Second, Seligman admitted that he was, indeed, a grouch—“a nimbus cloud in a house full of sunshine”—and that any achievements of his had been in spite of his grumpiness, not because of it.

Finally, raising Nikki should be about recognizing her wonderful strengths, nurturing and amplifying those strengths, and helping her find ways to use those strengths. Throughout the afternoon in the garden, Nikki showed such a playful and imaginative creativity. When looking at the situation through this lens, a less reactive response came to mind: How could I encourage and use her talents to get the gardening done in a way that helps me, and is still engaging for her?

Beyond improving his relationship with his daughter, Seligman’s epiphany inspired him to set out to change the study of psychology.

He began with two simple questions, the seeds that would sprout into the game-changing field of positive psychology:

How can the decades-long focus on fixing patients be complemented with a new focus on actively enhancing their lives?

And what if every person was encouraged to nurture his or her strengths, rather than scolded into fixing their shortcomings?

Stuck in Fix-It Mode

In the same way that it was instinctively easy for Seligman to see what was wrong

with his daughter’s behavior in that moment, we humans have a funny way of fixating on our own deficiencies, and ruminating on our mistakes.

As Marcus Buckingham—an ex-Gallup leader who pioneered the organization’s work on employee engagement that we covered in Chapter 2—said, “Most people are more fascinated by who they aren't

and how to fix it, instead of who they are

and how to leverage it.”

Fixating on your weaknesses may feel like a familiar concept.

Picture this everyday scenario: You say something inarticulately in a meeting, one of those “foot in mouth” comments. No sooner are the words out of your mouth than you are mentally beating up on yourself. “What was I thinking? What will they think of me? What shade and size is the pink slip that will be waiting on my desk?”

I still remember one of those instances from an early part of my career. During a debrief discussion after an important investment meeting with the partners of our firm, they asked what I thought about the investment opportunity. This was it. My chance to shine.

But I’m one of those “I need time to gather my thoughts first” types. I tried as best I could to disguise my unpreparedness and ignorance with a stuttering parade of fancy words like “barriers to entry” and “operating leverage,” but they quickly saw through the nonsensical jargon, which was a thinly veiled attempt to convince them that I actually knew what I was talking about.

I still remember the look on their faces, which screamed, “What in tarnation is this young pipsqueak even talking about?” I ruminated on this and ragged on myself for several weeks afterward. I still cringe thinking about it. Oy vey.

Stack a few of these up over time and it can start to feel like we have our own personalized blooper reel playing on repeat in our heads. This self-esteem shattering montage features our most earth-shaking face-plants, our most monumental meltdowns, and our most epic blunders.

The impulse to ruminate on our mistakes or weaknesses in this way stems from a thing known as “negativity bias,” and unfortunately, our brains are hardwired for it.

Innovations in MRI have transformed our understanding of how our brains work by allowing us to see which areas of the brain “light up” when research subjects are going through various experiences. It allows us to actually watch negativity bias happening in our brains as it occurs.

In one experiment, subjects were shown a collection of positive, neutral, or negative images while researchers monitored their brain activity with an MRI scanner. The scans showed that the negative images were generating a far stronger response in the cerebral cortex—the brain’s information processing center—than either positive or neutral images. The higher level of neural activity in the cerebral cortex produced by negative images shows that our brains are especially interested in these. In effect, our brains are saying, “Take note! This negative stuff matters!”

That’s why our blooper reel keeps playing on repeat in our heads. Our brains retain the unsavory stuff very well. They can’t get enough of it.

There is a sound evolutionary explanation for this. For long periods of human evolution, in hostile environments it was critical to our survival to be especially alert to negative things in life that posed a risk. This behavior regularly meant the difference between life or death.

In the Paleolithic era, you may have been enjoying a barbecued woolly mammoth steak and a warm glass of primitive booze made from chewed root, sitting around a roaring fire with your fellow hunters and gatherers—cavemen and cavewomen and cavebabies. But you were also on high alert—one eye on the next savory bite, and the other scanning the environment around you for bad stuff.

That rustle you heard in the undergrowth behind you just might be a saber-toothed tiger, and your brain needed you to pay attention. When the racket in the bushes was, in fact, a ferocious predator, and it pounced, you were ready to rumble. Your brain had you at the ready to chase off the predator with a blunt Smilodon tusk, or unleash your pet hyena on the encroaching predator to scare it off.

Whew! That was a close one.

You survived the semi-regular tiger ordeal, and because of the bravery you exhibited, you became so irresistible to your gawking tribemates of the opposite sex that you were able to procreate. And, voila, these “pay attention to the bad stuff” genes that kept you alive were passed down to the next generation. And the next. And so on.

But remember your popular caveman buddy, Mr. Happy-Go-Lucky? The one with the rosy cheeks and the perpetually sunny outlook? He didn’t fare so well.

When he heard the same commotion in the undergrowth, Happy thought: Nah. Just some kids messing around

. Then he went back to playing gleefully with a stick. Next thing he knew, he was caught in the maw of the massive beast. CHOMP.

As a direct result of young Happy-Go-Lucky’s early demise, his carefree, glass-half-full, “nothing bad ever happens to me” genes got wiped from the evolutionary gene pool.

In this day and age, saber-toothed tigers and similar threats aren’t as prominent in most parts of the world. But these outdated genes and adaptive responses are still in us, as relics of prior eras of human development. Unfortunately, they don’t serve us as well nowadays as they once did.

It is, in part, a perfectly natural biological response for humans like you and me to focus on the bad stuff. We feel the pain of loss or insult more strongly than we feel the pleasure of gain or praise.

So it might feel natural to obsess over what’s wrong with people, including ourselves, rather than focusing on what’s right with them. It’s because we are looking for hidden threats our brains want us to learn from.

Imagine that you are my parents—don’t worry, it’s just a thought experiment. One day, Little Dan Cremons brings his report card home from school. Drumroll, please.

|

LITTLE DAN’S REPORT CARD

|

|

Reading

|

A

|

|

Math

|

F

|

|

Science

|

B+

|

|

Social Studies

|

A

|

|

English

|

A-

|

|

|

What’s your most likely reaction?

Is it “Dan! Three As and a B? That’s amazing! You’re so smart, little fella. Let’s go get that new guitar you wanted!”

Or is it “Daniel

! How many times have we told you to pay more attention to your math classes? Do you want to go to college or not? You’re grounded until we see some improvement here!”

Negativity bias says that it is perfectly instinctive—though not entirely productive, as we’ll soon discuss—that we home in on the pitiful math score, and tune out the commendable performance in reading, social studies, and English.

We tend to closely examine the deficiencies and failures, and overlook the bright spots. This same phenomenon shows up in the workplace.

Picture the following everyday example: You and your team are looking at a metrics dashboard containing some of the key performance indicators that you use to run your business. Those KPIs are coded by red-yellow-green based on the degree to which they’re on track. Green means good, and red means something is off track.

As you scan down the dashboard in your weekly meeting, what jumps off the page? For most of us, it is the reds. We quickly home in on the issue areas. Oftentimes, this can be a useful inclination in a managerial context—as it can be a better use of management’s time to focus on helping things that are off track to get back on the rails.

This same negativity bias gives us a much sharper recollection of the “areas for development” from our prior performance reviews, than it does the glowing praise we received from our boss. Cognitively, the negative emotions associated with the critical feedback are processed more thoroughly and retained more prominently than the positive praise.

The problem with this, of course, is that when we spend too much time focused on what we don’t do well, we lose sight of where our unique brilliance lies. Our inclination to “find and fix” can cause us to fail to notice what’s of fundamental importance in life and leadership: What’s right

. What’s working

. What is brilliant

—or can be made so, as Seligman dreamed.

Some of us haven’t discovered our unique brilliance altogether. As the Buddha said, “Everyone is gifted here, but some of us never opened their package.”

As a result, we don’t figure out how to use our brilliance to maximize our impact on our companies, our communities, and the world. Sometimes, we don’t even believe we have something to offer.

What a tragedy. The world needs every ounce of our brilliance. It needs us to shine brightly.

Do What You Do Best

The founders of the Life is Good Company, known for their colorful T-shirts with whimsical little stick figures that spout profound life wisdom, once shared, “This is really what our whole brand, idea, and philosophy is based on: We all have limited resources, and when we wake up in the morning, we can decide to focus on what’s wrong with us, or we can focus on what’s right.”

In that same vein, Martin Seligman has simple but powerful advice for us: “The recipe for the ‘good life’ is knowing what your greatest talents are, and then recrafting your life—your work, your love, your play, your friendship, your parenting—to use them as much as you possibly can.”

This advice starts to seem even more sensible when we recognize that we as human beings face some real, practical constraints in life. Among them, the most finite and nonrenewable resource we have is our time.

In his book Outliers

, Malcolm Gladwell popularized the idea that it takes 10,000 hours of one’s time to truly master any particular skill, whether it’s playing the violin, figure-skating, or quantum physics.

This is known as “The 10-Year Rule,” since that’s roughly how much time, Gladwell observed, a dedicated person needs to become a master at something. In every one of life’s endeavors, achieving excellence requires a lot of time.

But there are only so many hours in the day, and days in the year. And if you spend your time trying to be a little bit good at everything, it statistically reduces your chances of being great at anything. This is a key concept for leaders to grasp.

It is for this reason that the book

First, Break All the Rules,

co-authored by Marcus Buckingham and Curt Coffman and based on one of the largest-scale studies of managerial effectiveness ever conducted, advises us: “Don’t waste time trying to put in what was left out. Try to draw out what is already in there. That is hard enough.”

[11]

* * *

When we have our eyes open for it, we can see the challenges with “trying to put in what was left out,” and the benefits of “drawing out—and using

—what is already in there” in everyday ways.

As I am writing this chapter, the NFL Pro Bowl Skills Showdown is playing in the background. Players who are chosen for the Pro Bowl compete in fun skills challenges like precision passing competitions, obstacle racing, and dodgeball.

Among the competitors is Jarvis Landry, a wide receiver for the Cleveland Browns who is quick as an antelope and has hands as sticky as a tree frog’s. Landry has just come off a pitiful performance representing the NFC in the passing challenge—a perfectly understandable outcome for a wide receiver competing in a quarterback’s competition.

But several minutes into the second round of NFC vs. AFC dodgeball, Landry finds himself on the losing end of a four-men-on-two situation in a must-win game. The stakes are high, and bragging rights are on the line.

In case you live under a rock and haven’t seen the 2004 film Dodgeball

, the truest underdog story in the sports film genre, there are essentially two skills that matter in dodgeball: throwing the ball in an attempt to strike your competitors, and evading or catching balls thrown at you. In dodgeball, getting opposing players out most often happens by hitting them with a thrown ball, but you can also get someone out by catching a ball.

Back to the action: there Landry and his teammate are, with two dodgeballs in hand and four competitors staring them down from across the centerline, like a couple of water buffalo surrounded by a ravenous pack of lions.

In an unusual strategic move, Landry rolls his two balls over to the other team—which is like giving an opposing army your last two missiles. This leaves him virtually defenseless since you can block an opponent’s throw using a ball in your own hands to bounce the attacking ball away.

But Landry has a plan. You see, he gets paid $15 million per year to catch

balls thrown at him, not to throw

balls He is a receiver, not a quarterback. So he gives the opposition more balls to throw at him and waits for the attack. Now he’s left with only two options: to dodge the opponents’ balls or make a clean catch, which would knock his opponent out of the game.

Two of the contenders take aim at Landry and fire their soft foam ammunition almost simultaneously, right on target. Landry catches the first ball, discards it, and a split second later catches the second incoming. Two opponents out! The contest is down to two-on-two.

But just as momentum is building, Landry’s teammate’s ball gets caught by a sure-handed opponent. He’s out. Two-on-one!

Landry is the last man standing on his side. He uses his own ball, clutched tightly in both hands, to block a perfectly aimed throw heading straight for his midriff. On the attack, one of his two opponents makes a colossal error, foot-faulting on the centerline and suffering instant and embarrassing disqualification. It is now one-on-one!

Landry, a ball in each hand, squares off with his remaining opponent. A perfect throw comes straight at him, with the speed and precision of a sniper shot. Landry speedily discards his own balls with a flick of his hands and catches the incoming missile. It’s all over. Landry prevails!

Apart from reminding us how much fun a good ol’ fashioned game of dodgeball is, this example also illustrates a key principle of the Blue Flame in action. As evidenced by his pitiful performance in the passing challenge, Jarvis Landry isn’t a good thrower—and he doesn’t really try to be. But he is

a great catcher, and he knows to lean on his talent heavily, especially when the stakes are high.

How to Think About Talents

Each of us is profoundly unique, and not just in a feel-good, motherhood-and-apple-pie kind of way. (Cue the cheek-pinching from Grandma—“You’re such a unique and special kid!”)

Think about it. You are the first person ever to be born with your unique genetic makeup. This individuality makes each of us one of a kind—genetically, psychologically, and cognitively—given that the makeup of each of our brains is completely unique.

Research has shown that even identical twins don’t actually have identically expressed

genes, despite starting life with a matching genetic blueprint.

This unique brain wiring equips each of us with our own unique set of talents.

But what does talent

mean? The term can become misconstrued, as it often gets mixed up in a buzzword stew with other similar terms like “strengths,” “skills,” and “unique abilities.” At their core, these ideas all refer to roughly the same general concept: things we’re good at and areas where we can perform effectively.

But to really understand and appreciate the power of talents, it is important to drill down into the nuance.

When we talk about talents, do we mean a talent for skateboarding, or business finance, or for telling jokes? Or are talents things like empathy and compassion? Or technical things like knowing how to write code or perform open-heart surgery?

The book I referenced earlier, First, Break All the Rules,

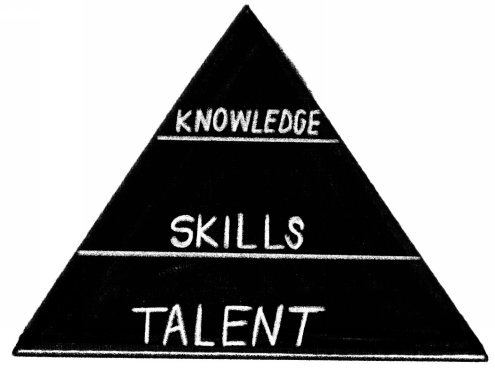

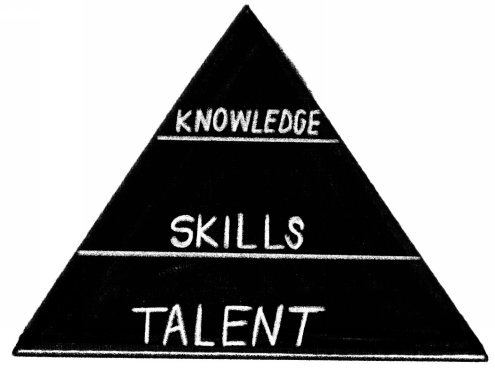

offers one of the more useful constructs for understanding talents.

The book distinguishes between knowledge

, skills

, and talent

, three interrelated but distinct ideas that often get conflated. Let’s break it down.

Knowledge

refers to things that you know

, and comes in two flavors: factual and experiential.

Factual knowledge

is the information we have acquired as we go through life. For instance, I know that the square of the hypotenuse of a right-angle triangle is equal to the sum of the other two sides squared. I also know that a discounted cash flow analysis will give me a useful measure of the value of a company, and that Steely Dan is the best rock band in history. These are pieces of factual knowledge, things we have come to know and understand because we learned them clearly and explicitly. Okay, fine, the Steely Dan example might be subjective.

Experiential knowledge,

on the other hand, is the knowledge we acquire about certain patterns and connections between things. Your experience of playing tennis tells you that a ball served in a certain way is likely to bounce up at a particular speed, height, and direction, or your experience of working with people across different business functions tells you that a particular person will likely be most effective in a certain role.

By contrast, skills

are proficiencies that can be learned

. You can learn how to play the euphonium, how to serve a tennis ball at over a hundred miles an hour, or how to do double-entry bookkeeping. We can learn new skills

until late in life, provided we stay in good shape mentally and physically, and our underlying talents

lend themselves to the development of these skills.

Talents

are neither skills nor knowledge, but they lay the foundation for both.

First, Break All the Rules

defines a talent as “a recurring pattern of thought, feeling, or behavior

.” That is, an ability or way of thinking that tends to show up for you time and time again, in different contexts and situations. You’re most likely already thinking of the talents you know you have at this moment. And no, being able to sing every word of “Bohemian Rhapsody” in near perfect pitch is not a talent, that’s a skill.

Here’s an example. A talent of mine is envisioning

: picturing what could be there when nothing is. I am able to apply this talent constructively in all sorts of ways, including in helping leadership teams to imagine what their vision for the future could look like. Or imagining how I want my new deck to look when there’s nothing but a patch of dead grass there today.

Envisioning isn’t a new pattern for me, it has been with me for a while. It’s this same talent that I put to work for hours on end during my childhood, sketching elaborate houses or cities on graph paper. It’s the same talent that consumed endless hours of my teenage and college years as I wrote and improvised music with other musicians.

Envisioning has been my trusted wingman for as long as I can remember. And, using it over time and in different stages of life, I’ve only sharpened it and learned to use it more skillfully. This regular pattern of envisioning has strengthened the neural pathways in my brain that are responsible for this talent. At this point, I probably couldn’t shake it if I tried.

As is the case with many of our predispositions—or talents—they can often come off as abnormal or counterproductive to people who don’t see their value, or when used in the wrong context. My wife, for instance, frequently has to nudge me back into consciousness when I get lost in an imaginative daydream when we’re out to dinner. She’s threatened to make me wear a canine shock collar to zap me back to attention, but luckily for me, she is a bit self-conscious about the fact that this might be frowned upon in a public setting.

There is surely some amount of innate brain wiring that is responsible for this talent. And some of this talent probably arose from adaptation early in my life. Some nature, and some nurture.

However much of this talent is attributable to nature

(biological predispositions), and however much is attributable to nurture

(the influence of one’s environment), most of our talents tend to take root early in life and lay the foundation for much of our skill and knowledge attainment over time. If we have the seeds of the precision

talent in us early in life, chances are, we will become good at (and enjoy) the skill of algebra

when we get into school. We may naturally gravitate toward being an accountant when we get older.

Over time, our talents strengthen and grow more powerful if they are put to good and constant use.

This idea of “nature vs. nurture” as it relates to talent formation is a complex area, but when you boil down the research, think of it like this: we are all born with the seedlings of unique talents (this is the “nature” part, based on the unique ingredients baked into our DNA). These seedlings may get watered, or in other cases dried out, based on a host of “nurture” factors, like our environment, upbringing, access to resources, effort, hard work, and deep practice.

Some people’s seedlings—if watered by training, exposure, and the environment they develop within—sprout into a very visible, prominent talent. Talents like intuition, or creativity, or empathy, or persistence. And like muscles, the more we use these talents, the stronger they become.

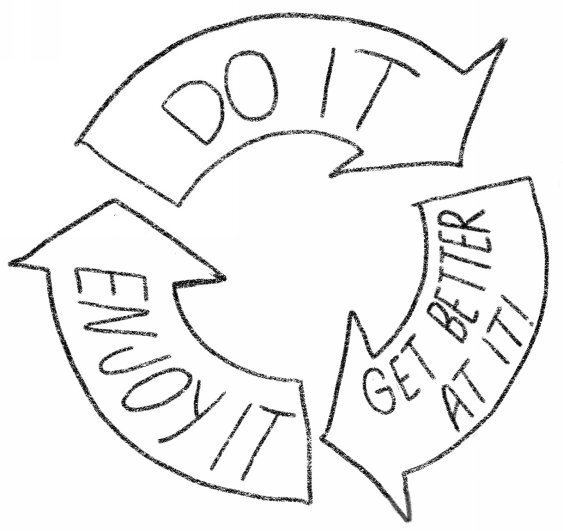

In this way, talent development becomes self-reinforcing.

Let’s say some combination of your nature and your nurture conspired to create in you a budding talent for language and abstraction. And let’s say you learn that this talent can be applied to writing poetry. So, you give poetry a whirl and it feels good to do something that plays nicely with how your brain seems to be wired. You start to enjoy writing poetry and you do it more and more often. And as you do it more often, your talent for language and abstraction and your skill for writing poetry strengthen. And so the pattern continues.

It is in this way that a powerful virtuous cycle

tends to form when we understand and lean into our talents.

Talents in Action

“The person born with a talent they are meant to use will find their greatest happiness and success in using it.” —

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

Lori Goler, Facebook’s head of human resources, had been following the work of Buckingham and Coffman (the guys who wrote First, Break all the Rules

and were pioneers of the strengths movement) as she built and led successful teams for juggernauts like eBay and Disney.

She instituted their core idea—focusing on strengths, not fixing weaknesses—

as a centerpiece of Facebook’s wildly successful engagement-focused culture. She notes that, “While intuitively it seems ‘nice’ to match people’s strengths to their roles in order to maximize engagement, the success of the practice goes much deeper than that.”

To understand how this idea has created such a vibrant and high-performance environment at Facebook, we must dip our toe into the research completed in the 1970s at the University of Chicago by Hungarian psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi. His groundbreaking idea, known simply as “flow,” centers around an “optimal state of consciousness where we feel—and perform—our best.” Csikszentmihalyi suggested that we experience flow when we are experiencing conditions of “optimal challenge.”

When things are too easy, we quickly become bored. When things are way beyond us, we feel anxious and dejected. But, when we are faced with a challenge that plays to our talents and stretches us to the limits of what we can achieve—but is not impossible—we can experience “flow.”

Flow is so powerful that in a ten-year study conducted by McKinsey, top executives reported being five times more productive when in flow.

[12]

When we are experiencing flow, we are able to concentrate intensely for long periods of time, and often fail to notice how long we have been absorbed in our task. We feel we are working “at the height of our powers,” with relevant information coming readily to mind and solutions to complex problems presenting themselves clearly.

On a collective level, when a group of people each find their flow states, they can achieve a thing called social flow. If you set foot in a Facebook office, you can feel this flow immediately. The place feels alive, a community of committed, mission-aligned people who—independently and as a collective—seem totally dialed-in. They appear to be vibrating on the same wavelength, like a world-class jazz ensemble immersed in improvisation, who seem to be operating from a shared group consciousness.

Insiders and outsiders alike attribute Facebook’s meteoric success, in part, to the emphasis on creating a potent culture focused on tapping into the native genius of its people, and the sense of flow that doing so can create.

Based on data collected by Payscale from 33,500 tech workers, Facebook employees were the most satisfied (96 percent) and the least stressed (44 percent) of the top eighteen technology companies in the study. Facebook was number two overall (and number one in Technology), in Glassdoor's “Best Places to Work in 2017.” They maintained a rating of 4.5 out of 5 stars, with 92 percent of employees likely to recommend the company to a friend, and 92 percent of their employees had a positive outlook for the company’s future.

[13]

In a knowledge business like Facebook, the ability to retain great talent—in an age where there is cutthroat competition for the best technical talent—is everything

. As Goler says, “The thing that separates people who stay for a long time [from those] who make the choice to leave is how they score themselves [in internal self-assessments and employee surveys] on whether they’re playing to their strengths.”

But all this talk of using talents in the workplace necessitates that we have a clear-minded, high-fidelity view of what our talents are, and what they aren’t.

Remember Martin Seligman? The guy whose daughter Nikki told him to stop being such a jerk?

When Martin Seligman took that moment to heart, he was embarking on a quest to use the study and practice of psychology to help people lead richer and more fulfilling lives, instead of strictly focusing on people with problems that are in need of fixing. His research led him to the groundbreaking—but still rather commonsensical—conclusion that people will be happier and more fulfilled when they are doing what they can do best.

Working with fellow psychologist Christopher Peterson, Seligman created what is now known as the Values in Action Inventory of Strengths (VIA-IS), which set out to classify character strengths: things like Creativity, Love of Learning, Perseverance, Kindness, Social Intelligence, Teamwork, and Humility. They identified twenty-four strengths in all.

Using their strengths inventory, Seligman and his colleagues set out to see what happened when people identified their core strengths and began making better use of them in their daily lives and at work.

Compared to the control group, participants who used their strengths in this way

for just one week

reported increased levels of happiness that

persisted for six months.

[14]

Other studies showed that when people were encouraged to make greater use of their core strengths at work, they developed a greater passion for their work, and that this in turn led to a greater sense of well-being and

better work performance.

Elsewhere, Donald Clifton, Curt Coffman, and Marcus Buckingham conducted a survey of 80,000 managers in 2,500 different business units of various kinds. Their goal was to further understand the effect of strengths-use at work.

The survey’s findings proved the basic principle of the “strengths” movement, one that leaders like you and me need to take note of: the most objectively successful managers weren’t fixated on trying to correct people’s weaknesses; they instead focused on playing to people’s strengths. When they did this, they maximized the contributions of their employees, and made them happier and more fulfilled in their work.

The research led to a very important insight: that “casting is everything.” It turns out that the best way to turn talent into performance is to put people in roles where they are doing what their talents have them hardwired to do best.

What’s more, studies have even drawn a connection between greater use of strengths and greater income.

* * * * *

As a culture, we seem to have gotten fixated on our weaknesses rather than on our strengths. The culprit is, of course, probably that old negativity bias.

Until very recently, medicine and psychology, for understandable reasons, have tended to focus on how we can fix things that go wrong for people rather than on how we can help them to thrive and flourish—and not get sick in the first place.

For decades, many companies have worked on the unconscious assumption that part of the responsibility of a manager is to try to mitigate the worst effects of their workers’ built-in deficiencies and weaknesses. After all, many managers end up becoming managers because they are effective problem solvers, and the people they manage are walking bags of problems—weaknesses—that are ripe for the solving.

But today, we are waking up to the exciting realization that people in the workplace are not defective machines that need fixing. Instead, we now know that when we help people understand their talents, and encourage them to focus on doing things that best leverage those talents, they become happier, more fulfilled, and importantly, more productive. When we start to embrace this way of thinking, we are able to take the first step toward sparking a raging inferno of Blue Flames within our team.