Chapter 5. Discovering Our Talents

“Everybody has talent. It’s just a matter of moving around until you’ve discovered what it is.”

—George Lucas

One of America’s most recognizable and stylish fast-food barons, Colonel Harland Sanders, was fired from a dozen jobs before he franchised his secret recipe for “Kentucky Fried Chicken” for the first time at age 62. Before that, he was a life insurance salesman, a lawyer, and a ferry boat operator.

World-famous fashion designer Vera Wang pursued careers as a figure skater and a journalist before she first tried her hand at designing a wedding dress—her own. A year later, she opened a small boutique and began designing bridalwear at age forty, and the rest is history. Wang went on to become arguably the most illustrious and successful bridalwear designer in the world.

Sara Blakely, founder of lifestyle brand Spanx, began her career as a Chipmunk at Disney World, failed her LSAT twice, and sold fax machines door-to-door before she realized that she could apply her talent and skill for selling in a way that was more fulfilling to her. She recalled in an interview: “I knew I was good at selling and that I eventually wanted to be self-employed. I thought, instead of fax machines, I’d love to sell something that I created and actually care about.”

These examples illustrate that discovering what you can do best can take time, and as George Lucas said, it requires “moving around.”

Here is a way to think about the process of discovering and steering yourself toward your talents.

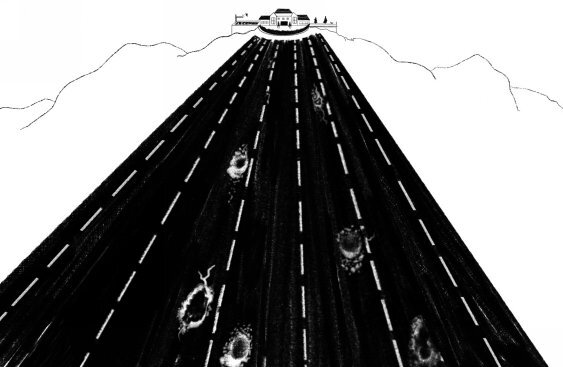

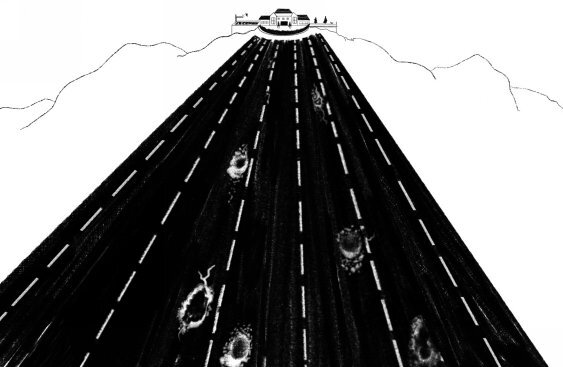

When we are young, life stretches out before us like an expansive twenty-lane highway. Picture, if you can, the city of Houston’s famed Katy Freeway, which boasts a whopping twenty-six lanes in certain parts. Like this stretch of Interstate 10, early on, life is a vast and wide-open road to explore.

Sure, each of us is born into a different environment, and has access to different levels of resources. This means that the guardrails on life’s highway might be tighter for some than for others, and our opportunity for exploration more limited. Unfortunately, because our world is constructed in an unequal way, some lanes of the highway may be closed to those who were born into less supportive or advantaged circumstances.

However wide your highway is early on, these early years are the time for exploration, for moving in and out of the different lanes on this expansive road of life: sciences, sports, arts, the outdoors, welding, basket weaving, computer programming, relationships, and so on. It is a time for discovery, and for trying things. For tossing things against the wall and seeing what sticks (metaphorically, and sometimes literally). Neurologically, our brains are especially malleable during these earlier years.

We each start off with certain advantages endowed by our unique genetic brain chemistry. This makes certain lanes of that many-lane highway feel smoother, faster, and lower-drag than others. In my own case, the math and sciences lane felt much faster and smoother than the reading comprehension lane. I traveled in both, but my early seedlings of talent for logical thinking—the X-to-Y-to-Z type of thinking—made the ride much smoother in the math lane than in the American history lane.

Sure, driving in the rutted history lane was a valuable ride at the time, as it helped me to slightly sharpen otherwise dull talents like critical reasoning, and build resilience. My determination to get an A in a subject that came less naturally helped me hone what went on to become very important talents later in life: persistence and grit. But nonetheless, it was a bumpier lane, which led me to rule out the possibility of steering my life toward a career in historical studies.

For most people, a good number of lanes remain open for much of our teens and early twenties, especially for those who have the opportunity for post-secondary education. Sometimes, new lanes open up as college introduces us to entirely new disciplines to explore. When used correctly, high schools and universities can be great playgrounds to help us discover our talents.

But as we grow older, it’s sensible to start getting clearer on where we’re driving toward, and narrowing down which lanes we’re driving in. By then, if we’ve been lucky, we’ll have had lots of opportunities to switch lanes, to see which one allows us to go fastest, which is the smoothest. We’ll have a feel for which lanes feel bumpy, and start to learn to move out of those lanes to avoid the potholes. This narrows the amount of road we are interested in navigating and starts steering us toward traveling in the lanes where we feel like we can really put the pedal to the metal—those lanes where our strongest talents lie.

Focusing on our core talents—navigating to the smoothest lanes, the ones where we sense we can really start to motor—gives us the best chance of kicking that virtuous cycle we discussed in the last chapter into gear.

But here’s the struggle for many people: it can be difficult to see our talents clearly. (Spoiler alert: This is where you

come in, leaders!)

Alex Linley, author of

Average to A+,

is another pioneer in strengths-based research. His research highlights the fact that the majority of people—a full two-thirds in Linley’s experiments—could not identify what their core strengths were.

[15]

Of course, if we don’t know what our talents are, it is impossible to focus on using them to their fullest potential.

In order to use our talents, we need to, as the ancient Greek aphorism goes, “know thyself.”

In his book, Linley asks a few insightful questions that can help you deepen your understanding of your talents, and help the people you are leading to do the same:

●

Is there something you remember you always did when you were a kid, something you liked and were good at that you still do?

●

What makes you feel comfortable with yourself and makes you think, “Yeah, this is the real me; this is what I do”?

●

Are there certain things that come easily to you—things you seem able to do well without having to try too hard?

●

What do you find it easy to concentrate on, maybe for long spells, without drifting off or losing focus?

●

Can you think of something that you seemed to learn surprisingly quickly?

These are the types of questions you will have the chance to use with your people as you are having Blue Flame conversations.

These questions are critical because, for many of us, our talents can feel shrouded. We struggle to see ourselves clearly, to recognize our own gifts and strengths. And, if we do catch some inkling of them, we may not embrace them: “Who am I to be talented?”

Herein lies one of the most central and significant responsibilities of a leader: to help our people discover and understand their talents. It is only then that we can work with them to put them to their best use.

Leaders as Flame Spotters

From his shabby 64-square-foot abode, which sat over 8,000 feet above sea level and gave him a 360-degree view of the sprawling Los Padres National Forest, Tom Fusek kept watch. He had a real knack for staying focused and vigilant—two of his core talents—which he put to good use scanning the mountains in an intense and systematic way every fifteen minutes.

Tom was a fire spotter, known affectionately to some as the “freaks on the peaks.” For generations, these guardians of our wilderness have been stationed proudly atop some of the highest lookouts.

At the profession’s peak—pardon the pun, but I couldn’t help myself—there were over ten thousand fire lookout towers in the US, monoliths soaring several stories above the ridgeline like protectors standing tall over the lush valleys below. Each of these perches was inhabited by fire watchers, the watchdogs of the great outdoors armed with binoculars and a radio, constantly scanning the landscape for any signs of smoke.

Today, fire-watching is a dying profession. Technology like drones and airplanes, and policies that require foresters to let fires burn, have caused many fire watchers to hang up their binoculars for the last time.

But despite their near-extinction, the legacy of flame spotters has a lot to offer leaders like us.

We need to foster a new generation of “freaks on the peaks”—leaders who are constantly scanning their teams, keeping watch for latent and budding talents in our teammates, and always on the lookout for even the faintest blue sparks waiting to be ignited.

But unlike flame spotters, we want

the fires to break out. When we notice even the faintest spark of talent in our people, our job as leaders is to douse those sparks with gasoline (metaphorically, of course), blast them with oxygen, and watch ’em burn brightly.

Too often, people’s talents go undetected, like precious gold buried just beneath the earth’s surface. We all miss out as a result.

As someone who has interviewed hundreds of job applicants, I know that slightly befuddled look people often show when faced with the classic interview question, “What are you best at?”

It isn’t that these people are dense. The reality is that it can be tough to develop an objective view of what’s going on in our own heads, and accurately assess our own level of competence.

Sometimes we recognize that we are good at something, but we underestimate

our level of excellence. We think, “Well this is easy. Everyone must be good at this.”

Other times, we overestimate our level of talent. We assess our abilities as greater than they actually are. Like that time I stepped up to the karaoke microphone at the office party to do my rendition of “Born in the U.S.A.” I knew what the song sounded like. I could hear Springsteen’s voice in my head. So, clearly, I could reproduce that sound, right? How hard could it be?

The painful answer is: harder than it seems.

The cognitive bias that explains this is known as the Dunning-Kruger Effect

, named after two scientists at Cornell University who investigated people’s perceptions of their own competency.

In the Dunning and Kruger study, students were asked to undertake tests in grammar, logic, and humor. They were then asked to assess how they felt they had performed in the tests.

In a nutshell, the students who had performed worst in the tests—the ones who had scored only 12 percent in reality—predicted their score would be a whopping 62 percent.

It’s a similar type of (misguided) conviction that had me thinking that my rendition of “Born in the U.S.A.” pretty much nailed it, while my poor colleagues were cringing in horror.

As author and organizational psychologist Tasha Eurich put it, “When people are steeped in self-delusion, sometimes they are the last ones to find out.”

In direct comparison, the students who scored highest of all, at around 85 percent, significantly underestimated

their predicted score—though not by such a monster margin. That’s a lot like Bruce Springsteen himself thinking that his gig was going just okay, but not that great. But meanwhile, the crowd is going completely nuts.

What is fascinating is that when the students were shown their actual results, the best achievers changed their self-assessment. They recognized that they were better than they had realized they were. Interestingly, the lowest achievers, sadly, did not change their self-assessment. They still thought they were far better than they were in reality.

Dunning and Kruger’s main conclusion was that people with a serious lack of skills in any area also often lack the competency to recognize their lack of skills. This helps to explain, in part, why people who know diddly-squat about something can be so infuriatingly insistent that they are right and you are wrong.

In other words, our ignorance can sometimes be invisible to us.

But the main takeaway for us flame-spotting leaders is the other side of the same coin: some talented people have a tendency to underestimate their strengths. This is perhaps the blindspot created by our negativity bias.

It’s important to note that this is not just modesty, or even false modesty. It simply doesn’t always occur to talented people that they are, objectively, extremely good at certain things. They have normalized their level of competency in their own minds.

One of the primary responsibilities that we have as leaders—and I think one of the most important and

exciting responsibilities we have—is to seek out a clear understanding of everyone’s talents, to help each individual develop a clear understanding of their own talents, and to shine a big, bright spotlight on those talents.

In the January 2020 edition of the Harvard Business Review

, Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic, chief talent scientist at ManpowerGroup, and Jonathan Kirschner, CEO of a global leadership development and coaching technology firm, put it simply: “The ability to see talent before others see it, to unlock human potential, and find not just the best employee for each role, but also, the best role for each employee, is crucial to running a top-notch team. In short, great managers are also great talent agents.”

Talent agents—what a powerful and evocative way to frame the role of a leader.

We must meticulously observe those whom we lead and take note of spikes in enthusiasm or effectiveness. When we notice these spikes, we can ask ourselves and our teammates, “What talents are on display in this moment?”

For instance, I might say, “Johnny, I noticed such remarkable precision

when you presented your summary of the quarter-in-review yesterday. Your command of the details of what drove the business was impeccable. Did you notice that about yourself? What was going on for you at that moment?” Johnny will then help me understand what this talent looks and feels like to him (which will help him to really internalize and own his strength), and we will together figure out ways to help Johnny lean into this talent even harder.

Jesuit priest and author John Joseph Powell reminded us of the value in doing this at a human level: “It is an absolute human certainty that no one can know his own beauty or perceive a sense of his own worth until it has been reflected back to him in the mirror of another loving, caring, human being.” This is Blue Flame spotting.

* * *

Like him or not, Bill Belichick, coach of the New England Patriots and one of the winningest in NFL history, is a legendary flame spotter. He’s a master of noticing talent and potential in unsuspecting places. He built the Patriots into an offensive powerhouse around late-round draft picks, the “leftovers” of the draft class. Some of the team’s most prolific offensive producers in recent years—Tom Brady (sixth round pick), Julian Edelman (seventh round pick), Danny Amendola (undrafted), LeGarrette Blount (undrafted)—are among the most noteworthy examples.

One of the key ingredients to Belichick’s success has become his uncanny ability to spot latent talent—talent that may not be obvious to others on the surface—that has the ability to fit well into his offensive system.

Take Patriots wide receiver and punt returner Julian Edelman. Edelman spent his college career at College of San Mateo and Kent State University, both low-tier football schools. A quarterback in college, he set several records as a passer. But undersized and unknown, Edelman was not invited to the NFL Combine, the annual invite-only showcase where NFL prospects have a chance to show their stuff to scouts.

Standing only 5'10", Edelman was way undersized as a quarterback, in a draft class with several great ones. His success in college was discounted because he’d been playing against lower-caliber competition. When it came to getting noticed and drafted, the odds were understandably stacked against him, and he flew well below professional scouts’ radar.

But on a whim, the Patriots agreed to attend a private workout with Edelman.

Belichick recalled, “We’re not thinking he can play quarterback, so we’re like, ‘Okay, what would we do with Julian? Is he a receiver? Is he a punt returner? Is he a defensive back? Is he maybe a guy who can play multiple positions in the kicking game?’ ”

Belichick spotted a few things about Edelman that other scouts seemed to be overlooking. First, Edelman had “an intensity that was hard for [opponents] to handle.” He spotted this in a blowout loss that Kent State suffered at the hands of juggernaut Ohio State. Edelman fought tirelessly even as the outmatched Kent State team’s deficit widened. Some coaches might have seen this whooping as a blemish on the quarterback’s résumé, but Belichick noticed relentlessness

—a talent—in the undersized quarterback. This relentlessness was key to the offensive culture that the coach was building in New England.

Second, Belichick saw a work ethic unlike few he had seen before. Conversations with his coaches and teammates painted a picture of a leader with a mental toughness and dedication that was unmatched in the Kent State locker room. He was, as his teammate said, “always grinding.”

This diligence and devotion went on to make Edelman somewhat of a legend in the Patriots’ locker room. Fellow Patriots superbowl hero James White remarked, “That guy works extremely hard. He’s the first guy in here and leaves last. He’s catching tennis balls at six in the morning. As soon as you step in here as a rookie, you see how hard he works, and the results show.”

Despite not having some of the prototypical talents that tended to attract NFL teams at the time, Edelman got scooped up by the Patriots in the 2009 draft. Why? Because Belichick—a black-belt flame spotter—could see clearly the talents that he would be getting in the young rookie, and knew that those could be applied effectively within his system.

This seemingly risky move paid off big-time, as he went on to become one of the key players in three Superbowl seasons for the Patriots, collecting awards like Superbowl MVP and Most Receiving Yards along the way.

* * *

Blue Flame spotting is the stuff of great leadership, the type of leadership that gets the best out of people and translates it into extraordinary results. And one of the greatest opportunities a Blue Flame leader has is learning to notice

. To simply notice. Noticing what energizes the people in your charge (and what doesn’t). Noticing when they are at their best. And noticing the underlying talents that allow them to function at that level.

When we do this as leaders, it puts us in a position to then put our teammates’ talents to their best use.