A NOTE SANG out in the air, and that note was the sound of the edge of a freshly released knife blade racing toward Lisa’s and Doctor Proctor’s necks. Soon it would separate their heads from their bodies, and history would be changed. No girl named Lisa would ever live in the red house on Cannon Avenue and no Doctor Proctor would ever live in the blue one. Fart powder, fartonaut powder, and French nose clips would never be invented. And the time-traveling bathtub would be invented by someone else, specifically Proctor’s rather evil assistant, Raspa. True, Nilly was on his way toward the stage, but he was too late. Bloodbath had already released the guillotine blade.

Future prospects were—in other words—rather bleak.

Lisa closed her eyes.

Then the knife was there, and the whistling stopped with a loud clang.

Lisa was dead. Of course she was dead, she’d just been decapitated, and besides she was surrounded by a deathly silence. True, it was a little weird that the sound the blade had made when it hit her was clang! instead of chop! but so what? When she thought about it, it was a little weird that she had heard any sound at all since she didn’t have a head anymore. Actually it was weird that she was thinking all this stuff what with being headless and all. Lisa hesitantly opened her eyes, half expecting to see the inside of a woven basket and—above her—her own headless body. Instead she was looking out at the crowd, which was staring at her and the professor, speechless, their mouths open, looks of disbelief on their faces.

Then she heard a familiar voice:

“Dear citizens of Paris! The day of liberty has arrived! Just as my saber has saved these two innocent children of the revolution, it will liberate you, yes, YOU, from tyranny, exploitation, corrosion, and other miseries!”

Lisa turned her head. Just above her own and the professor’s necks, she saw a saber blade with its tip jammed into the guillotine. The saber had obviously stopped the guillotine blade at the last possible nanosecond before they’d both become headless. Or bodyless. Depending on how you looked at it. Next to her she heard the professor moan quietly, “Are we still alive?”

“Yup,” Lisa whispered, her eyes following the blade of the saber out to its handle, to the small hand holding on to the saber, and to the little guy in the blue uniform who was addressing the crowd while gesticulating wildly with his free hand: “I promise to lower all conceivable kinds of taxes and fees on tobacco, gasoline, toys, and vacation cruises!”

“Nilly!” Lisa hissed quietly. “What are you doing?”

Nilly stopped and whispered, “Shh! I’m good at this. I recently convinced seventy thousand guys with rifles to go home. Just listen….”

Nilly cleared his throat and raised his voice again. “I will do away with toothaches, P.E. class, and that slushy, sticky snow that’s no good for skiing on. And I will do away with the death penalty. Especially for nutty professors and quarrelsome little girls. If you will agree with me on this, everyone will get a PlayStation for Christmas!”

He lowered his voice again and whispered, “You see? They’re nodding. I’m winning them over.”

“Not quite, I’m afraid,” Doctor Proctor said.

And the professor appeared to be right. An irritated murmur was spreading through the crowd. A few people were shaking their fists at the stage.

“We want a beheading!” a voice screamed from somewhere in the crowd.

“We want to see this little guy’s head chopped off too!” someone else yelled.

Behind him on the stage Bloodbath had recovered from the shock of seeing a little boy come swooping in, jabbing his saber into the guillotine to stop the blade and—even worse—possibly dulling the blade so that it would have to be sharpened yet again. But this little boy was obviously a raving lunatic, so Bloodbath and the two guards approached him from behind with the greatest of care.

“But my dear countrymen.” Nilly laughed good-naturedly. “Aren’t you listening? I’m going to do away with rain on Sundays!”

A slice of bread with brie on it came sailing out of the crowd and was about to strike Nilly. He turned to avoid it and caught sight of Bloodbath and the two guards, who had their swords drawn.

“And a raise for everyone!” Nilly cried, but he didn’t look that confident anymore. “Especially … uh, executioners and guards with mustaches. What do you guys say to that?”

But no one said anything to that. Bloodbath and the guards just continued to slowly close in on him, as did the crowd, its threatening murmur getting louder and louder.

“Darn it! I don’t get it,” Nilly mumbled. “This worked so well at Waterloo!”

“You’d better think of something else,” Doctor Proctor said. “And fast. They’re going to rip us to shreds.”

“Well, like what?” Nilly whispered. “I’ve already promised them everything! What do these people actually like?”

“I think,” Lisa said, “they like … music.”

“Music?” Nilly asked dubiously.

“Behead the little guy twice!” someone bellowed and several others said, “Oui!”

Nilly looked around in despair. He knew the jig was almost up. Soon, but not quite yet. Because wasn’t he a resourceful little guy who knew a thing or two? Maybe. He could run fast, he could lie so well that even he believed himself, and he could play the trumpet so that even the birds would weep with joy, and—

The trumpet!

He looked at the brass instrument that Lisa was still holding in her hand. And the next second he let go of his saber, hopped down from the guillotine, ducked under the guards’ arms, and snatched the trumpet. He put it right to his lips and blew.

The first two notes rose up toward the blue sky and just like that the larks and warblers stopped singing and the bees and blowflies stopped buzzing. As the third and fourth notes surged out of the trumpet, the threatening murmurs fell silent as well. Because unlike the Norwegian national anthem, this song was one everyone in the crowd had heard before.

“Isn’t that …?” said a buxom woman with two children on each arm.

“Why it has to be …,” said a farmer, using his pitchfork to scratch himself under his warm, red-striped hat.

But Nilly didn’t get any further, because then the two guards grabbed him under his arms.

“Get him into the guillotine,” Bloodbath shouted. “He tried to prevent two beheadings, which means we need to behead him three times! What do you say, people? Give me a C!”

“C!” replied the crowd. True, not as loudly or enthusiastically as Bloodbath had expected, but if there was one thing he knew it was how to whip them into a bloodthirsty mood:

“Give me a—”

“No!” The voice came from the crowd and was so small and frail that Bloodbath could have easily drowned it out. But it threw him for such a loop that he simply forgot to continue. In his time as executioner no one at the Place de la Révolution had ever talked back to him, protested, or spoken out against what had been decided. Because everyone knew that was tantamount to asking to be a head shorter themselves.

“Let him play the trumpet,” cried the voice. “We want to hear muthic! The way it uthed to be here on Thundayth.”

Not a sound was heard in the Place de la Révolution. Bloodbath gaped at the crowd, his face contorting into an enraged grimace, which no one could see because of his hood.

“Me,” the voice said. “Marthell.”

“Marthell?” Bloodbath repeated. “Marthell, now you’re going to—”

“I agree with Marcel,” another voice said. This one was hoarse and dry as a desert wind. “We want to hear the rest of the song. After all, it is the Marseillaise.”

Bloodbath was speechless again. He was staring at a bizarre, black-haired witch of a woman in a black trench coat.

“I want to hear the song,” called a voice from the very back of the crowd, followed by two approving pig grunts.

“Me too!” yelled a woman.

“And me! Play the Marseillaise, kid.”

Bloodbath turned toward the two guards.

“Humph!” he said. Then he gave a dissatisfied nod and they released Nilly. Not waiting to be asked a second time, Nilly put the trumpet to his lips and started playing. He wasn’t far into the first verse before people started singing along. Hesitantly at first, then more earnestly.

“Contre nous de la tyrannie

L’étendard sanglant est levé.”

Or, for those of you who don’t have your French nose clips on at the moment:

“The bloody banner of tyranny

is raised against us.”

Nilly leaped up onto the guillotine so that he was straddling the heads of Doctor Proctor and Lisa, both of whom were singing at the tops of their lungs:

“To arms, citizens,

form your battalions.

May impure blood

fill our gutters.”

There was no doubt about it. Those were some catchy lyrics. And even after Nilly stopped playing, people kept on singing. Out of the huge number of people singing, Nilly was able to pick out three voices: A high, frail voice with a bit of a lisp. A hoarse, desertlike voice. And behind him, Bloodbath’s gravelly vibrato.

“Let us release everyone who’s been sentenced to death,” Nilly screamed when the song was over. “We don’t want any more death. Because what do we want …?”

“What do we want?!” the people in the Place de la Révolution cried.

“Give me an L!” Nilly shouted.

“L!”

“Give me an I!”

“Give me a F!”

“F!”

Give me an E!”

“E!”

“And what does that spell?”

“Life!” the crowd answered. “Life! Life!”

By this point Nilly was so excited, worked up, ecstatic, and inspired that he just had to start singing. So he did, “There will be life here—yes, yes! And not death—no, no!”

Bloodbath ran over to the guillotine, unlocked it, got Lisa and Doctor Proctor out and onto their feet again as he brushed off their clothes, and asked with concern if they were all right. Obviously they were because they ran right over to the little lad in the uniform, each grabbed one of his arms and lifted him up while he kept singing, “There will be life here—yes, yes!”

Down in front of the stage people had started dancing and jumping up and down as they sang along. People were more animated than they’d been even during the bloodiest and most successful Sunday beheadings. Bloodbath felt a strange warmth, yes, a sense of joy spreading through his body at the sight of them, a delight that surged through him. It couldn’t be stopped, there was something about this irritating, simple little song. So, once the delight reached his throat, Bloodbath did something he had never done before in his entire career as Paris’s most dreaded executioner. He pulled off his hood and allowed people to see his face. And then, in an instant, the crowd stopped singing. They stared at him, appalled, because Bloodbath was not at all a good-looking man. But then he smiled broadly and chimed in in his booming vibrato, “There will be life here—rah, rah!”

And with that, the party was in full swing again. People ran amok. They were crazed, frenzied, zany, brazen, pizzazzy, and a bunch of other things with Zs in them. They didn’t even notice the three people sneaking away behind the stage, around the corner of the dreaded Bastille prison building and disappearing. They just kept singing and dancing and splashing red wine on each other. The song was long forgotten by the next day when most of them woke up with throbbing heads, aching hips, and sore throats, but not by Bloodbath. Bloodbath would keep singing this song for the rest of his life and would later teach it to his children and grandchildren, who would eventually move around quite a bit, to England, to Germany—and some of them even to a small town in Minnesota, where they would form the heavy metal band Meat Ball, which would become famous after being featured in the mockumentary There Will Be Life Here.

“DID YOU BRING the time soap?” Proctor asked breathlessly. He and Lisa and Nilly had left the Bastille behind and were now racing through the crooked streets of Paris. Lisa and Nilly had no idea where they were, but the professor seemed to know his way through the quiet Sunday alleys and lanes.

“I have a smidge,” Lisa said. “But I don’t think it’s enough for all three of us. I had to take a few detours to get here, you know.”

“I have a smidge,” Nilly said. “But I don’t think it’s enough for all three of us. I had to take a few detours to get here, you know.”

“Let’s hope if we combine it, it’ll be enough,” Doctor Proctor said as they came around a corner. “Have you guys seen Juliette? Is she waiting at the hotel?”

But before they were able to answer, Doctor Proctor stopped so suddenly that Lisa and Nilly ran right into him.

“Oh no!” the professor said. “Someone stole my bathtub. Look!”

But there wasn’t much to see since what he was pointing to was an empty square with just a few empty market stalls in it.

“Well, I guess someone got themselves a new bathtub,” Nilly mumbled. “What are we going to do now?”

“Where’s your bathtub, Nilly?” Lisa asked.

“Where you said you were going on that message in the bottle,” Nilly said. “The Pastille. Weird destination, by the way. I wound up in the middle of a big chicken coop.”

“Sorry, I mixed up Pastille and Bastille,” Lisa said. “If we don’t have enough time soap, we’ll have to get there before the bubbles are gone. But how will we get there? We don’t have any pigs.”

“Pigs?” the professor and Nilly cried in unison.

“Forget about it,” Lisa sighed, realizing that it would be too hard to explain. “What are we going to do now?”

“Yeah, what are we going to do?” the professor and Nilly cried in unison.

The three friends stared at each other, stymied.

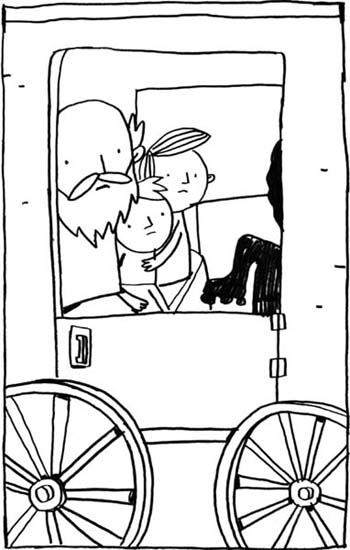

And as they stood there staring at each other, stymied, in the sunshine filtering down between the tall Parisian buildings, they heard the lively clopping of horseshoes and the creaking of large wooden wheels. They turned around. A brown horse with large black blinders came prancing around the corner. And behind it, a carriage. A driver was sitting on the front of the carriage, swaying back and forth and looking like he was about to fall asleep. He had big bags under his eyes, a tattered coat, and a moth-eaten top hat, black and tall as a stovepipe.

“Need a lift?” he asked with a yawn.

“That’s just what we needed!” the professor exclaimed. “Come on!”

They climbed in the door of the carriage, which started moving right away.

There was just exactly enough room for four people on the two benches, and that was also just what they needed, because there was already one person sitting in there. The brim of the passenger’s top hat had slipped down over his eyes, and he was obviously sound asleep, because his body was flopping back and forth as the carriage moved.

“Weird,” Lisa said.

“What is?” the professor asked.

“The driver didn’t ask us where we were going.”

“Elementary.” Nilly smiled condescendingly. “Obviously he’s going to drop this other passenger off first.”

“But we don’t have time for that!” Lisa said. “Should we wake him up and ask if it’s okay if we go to the Pastille first?”

The professor shook his head. “I’m afraid that won’t help, Lisa. I’m sure the bubbles will already be long gone.”

They sat there for a while contemplating this, and the only thing that broke the silence was the sound of the horse’s hooves, clopping against the cobblestones in a slow tap dance.

“Raspa was there,” Lisa said. “In the crowd. Did you see her?”

“No,” Doctor Proctor said. “But I’m not surprised.”

“Oh?” Lisa and Nilly said, looking at the professor, shocked.

“That was the idea—for her to follow you guys to Paris,” he sighed.

“The idea?” Nilly and Lisa yelled, you guessed it, in unison.

“Yeah. I sent you two down to her shop with that stamp so she would understand that I had succeeded in traveling through time, that I had gotten our invention to work. I knew that once she understood that, she would try to find out where I was and then come to steal the invention from me. Like she had tried to do when she was my assistant here in Paris.”

“Steal the invention from you!” Lisa exclaimed, agitated. “Why would you want her to come here, if that’s what she was going to do?”

“Because I was out of time soap,” the professor said. “And because I knew there was enough in that jar in the cellar to bring you two here but not to bring all three of us back. Raspa is the only one in the world who can make more time soap. I needed her here, simple as that.”

“Why couldn’t you just send Raspa a postcard and ask her to come?” Nilly asked.

The professor sighed again. “Raspa would never have voluntarily come to rescue me. She hates me.”

“Why?”

Doctor Proctor scratched his head. “I’ve wondered about that a lot, but I really don’t know. I never tried to deprive her of the honor of having invented time soap.”

“But …,” Nilly said. “How did you know that we would spill the beans so she would find out we were going to Paris?”

The professor smiled wryly. “First of all, there was the stamp and the postcard, which I knew would make her understand the situation. Second of all, you’re a whiz at a lot of things, Nilly, but keeping secrets isn’t exactly your specialty, is it?”

Lisa cleared her throat.

“Eh heh heh,” Nilly chuckled with a zigzag smile.

“But what do we do?” Lisa said. “How do we find Raspa and get her to make more time soap?”

“Well,” the professor said. “Finding her won’t be that hard.”

“Oh?”

“You think horse-drawn carriages just show up out of thin air right when you need them?”

Doctor Proctor nodded toward the sleeping passenger, and then looked down. Nilly and Lisa followed his gaze down to the floor. And there—jutting out from under the edge of the trench coat—was a wooden leg that ended in a roller skate.