THE 1918 OFFENSIVES AND ALLIED COUNTER-ATTACKS

At the end of 1917 the Central Powers regained the strategic initiative. Russia collapsed in the October Revolution and sued for peace. The French reorganised their armies following the outbreak of mutinies after the failed Nivelle offensives of April and May 1917, but were only capable of limited operations. The BEF had suffered 900,000 casualties during the year and the November offensive at Cambrai had been checked, while the Italians were on the defensive after the disaster at Caporetto. The Americans joined the war in April 1917, but had only 140,000 troops in France by January 1918. It was a golden opportunity for the Deutsches Heer (Imperial German Army), which had a narrow window in the first months of 1918 to win the war before the Allies recovered their strength and American forces tilted the odds once again.

The Oberste Heeresleitung (OHL) — the German Supreme Army Command — transferred dozens of divisions to the Western Front over the winter of 1917. German strength rose from 150 divisions in November to 192 in March; eventually 208 divisions would serve on the Western Front in 1918. As they gathered strength, the Germans trained approximately 60 divisions in infiltration tactics and reorganised the army so that these angriffsdivisionen (attack divisions) were close to establishment strength in manpower, equipment and transport. The remainder were classified stellungsdivisionen (trench divisions), with limited offensive action and mobility. First Quartermaster-General Erich Ludendorff, the de facto commander of OHL and master of the German war effort, planned the first offensive to open near St Quentin, at the junction of the French and British armies.

The German Army launched five offensives on the Western Front between 21 March and 15 July and captured large amounts of territory and prisoners while inflicting heavy losses in men and equipment. On 26 March French General (later Marshal) Ferdinand Foch was tasked with coordinating the Allied response. Foch’s role continued to expand until he was named Supreme Commander of the Allied Armies, with authority to coordinate all their efforts. By June the Allies had halted four attacks and Foch had assembled his reserves for a counteroffensive.

The Allies planned to contain any further offensives and then attack to clear three vital railway lines that were threatened with capture or interdiction. Allied intelligence identified the Champagne-Marne area as the likely location of the next German attack, which opened on 15 July. By now the Allies understood the German attack doctrine and staged a defence in depth rather than crowding front-line trenches. The new defence quickly halted the German advance. The planned French Tenth Army offensive instead became a counter-attack that eliminated the German bridgeheads south of the Marne River and seized the initiative for the Allies. Foch reopened the Paris–Nancy railway and continued the offensive, while the British Fourth Army, supported by the French First Army, pushed the Germans out of the Montdidier-Amiens corridor and relieved the pressure on the Paris–Amiens railway and the BEF’s lateral communications. The newly forming First American Army would reduce the St Mihiel salient south-east of Verdun, thereby opening the railway to Avricourt. Once the railways were secured, the attacks were to continue on a wide front to prevent the Germans concentrating their reserves. The broad advance would create numerous salients and force the Germans to evacuate unthreatened areas across the entire front to avoid being cut off.

The French counter-attack at Soissons on 18 July and the combined British-French offensive at Amiens on 8 August were both successful in achieving their objectives and inflicted heavy casualties on the Germans. Ludendorff cancelled the proposed Operation Hagen against the BEF in Flanders and planned a series of winter defensive lines to hold the Allied armies until the German Army could regroup and end the war on favourable terms. General Friedrich von Lossberg, one of Germany’s foremost defensive experts, suggested a withdrawal to the Hindenburg Line positions on 19 July following news of the defeat at Soissons, but Ludendorff refused.

The Germans made impressive tactical gains, but the offensives lacked operational and strategic cohesion. They had not split the BEF from the French Army, nor captured the vital railway and logistical centres at Amiens or Hazebrouck. In reality, the result was over-extended armies that had suffered enormous casualties. Historian Robert Foley estimates permanent (killed, prisoners and wounded unable to return to their unit) German casualties on the Western Front between March and July 1918 as up to a million, the German armies now 883,000 men below authorised strength. Growing numbers of desertions represented an additional drain on manpower, as was the influenza epidemic, which hit the Germans harder than the Allies. By August 1918, with American troop arrivals, the Allies held an infantry and artillery manpower superiority on the Western Front of 1,672,000 to 1,395,000.

Following the defeat at Amiens, OHL formed a new army group in the threatened area. Commanded by General Max von Boehn with General Lossberg as chief of staff, Army Group Boehn consisted of Second, Eighteenth and Ninth armies, stretching from Douai to Laon. The boundary between Second Army (General Marwitz) and Eighteenth Army (General von Hutier) was opposite the British Fourth Army front. Several German army commanders recommended retreating to the Hindenburg Line to shorten the front and release reserves, but Ludendorff refused, confirming his order to stand on the Somme and the Canal du Nord.

Map 1. The Western Front, 30 August 1918

Field Marshal Douglas Haig, commander of the BEF, maintained relentless pressure. He believed that the Germans lacked the means to counter-attack on a wide scale and informed his army commanders that ‘Risks which a month ago would have been criminal to incur ought to now be incurred as a duty.’ In concert with French attacks between the Oise and Aisne rivers, the British First and Third armies attacked on 22 August from Albert to Arras. The offensive culminated in the capture of Albert and Bapaume and the breaking of Ludendorff’s proposed ‘Winter Line’, the Drocourt-Quéant Line, east of Arras, by the Canadian Corps. Further south, the British Fourth Army, with the Australian Corps playing the leading role, broke the Winter Line at Péronne. The Canadian success was the critial factor in forcing the withdrawal of the German Seventeenth Army behind the Canal du Nord near Cambrai. With the Winter Line also compromised to the south, Second, Eighteenth and Ninth armies followed in succession, retreating between Arras and Laon. In Flanders, Fourth Army, positioned opposite the British Second Army and the Belgian Army, likewise began to withdraw.

From 4 to 10 September, Fourth Army, with III Corps on the left and the Australian Corps on the right, advanced 10 miles on a frontage of 14 miles, forcing the Germans to abandon their gains of March. By 10 September, German strength on the Western Front had dropped to 185 divisions, with only 19 classed as fit. Twenty-two divisions were broken up to provide manpower for the remainder. The withdrawal shortened the German lines and allowed reserves to be reconstituted. But the Germans had to hold their positions in the Hindenburg Line to allow time for additional positions in the rear to be sited and prepared. Army Group Boehn reconnoitred a fall-back position known as the Hermann Stellung, which ran east of the Selle River through the line of St Souplet to Le Cateau, 12 miles east of the Hindenburg Line. Behind the Hindenburg Line was unfortified territory, and if the Germans were to hold on through the winter, they had to prevent the Allies breaking through.

The Australian Corps, with the 3rd, 5th and 32nd divisions, advanced by brigade groups consisting of infantry, pioneers, artillery, engineers, Light Horse and combat support elements and successfully maintained contact with the German rearguards. The brigade groups functioned well, with the Light Horse troops proving useful along the wide frontages. The open advance was exhausting and brigades sought to rotate their battalions on a daily basis. Artillery support was generous, even if it occasionally missed fleeting targets due to distance or delays in communication. While the Germans pursued scorched-earth tactics that left the countryside barren and devastated, the engineers and pioneers quickly repaired the bridges across the Somme and cleared German mines and booby traps left during the withdrawal. Casualties were light, with 90 killed and 239 wounded in the advanced guard brigades. The Australian Corps relieved the rapidly tiring 3rd and 5th divisions, replacing them with the fresher 1st and 4th divisions in a bid to provide some respite to the front¬line troops. On 8 September Haig asked his army commanders to submit plans for future offensive operations.

Map 2. German withdrawals, August and September 1918

THE BEF AND THE BRITISH FOURTH ARMY

The BEF had expanded from seven divisions in 1914 to 60 divisions in five armies totalling 1.75 million men in 1918, including 550,000 artillerymen and 325,000 Army Service Corps (ASC) personnel. General Headquarters (GHQ) was sited in Montreuil and the BEF relied on six ports on the English Channel for the majority of its supplies. While the BEF held just 18% of the Allied line, by September 1918 its forces were attacking along most of their front to roll the Germans back. The nature of the advances led Haig to decentralise planning authority to his army commanders and concentrate on maintaining the operational tempo in conjunction with the French and American attacks. This represented a distinct change from the tightly planned offensives of 1916 and 1917. Historians Robin Prior, Trevor Wilson and Gary Sheffield all believe that this delegation increased Haig’s effectiveness as a commander and boosted the ability of his subordinate commanders to implement what was termed a ‘hands-off’ battle.

The BEF succeeded in pushing the Germans back — albeit at the cost of 650,000 casualties since the opening of the March offensives. Haig was under tremendous political pressure as a result of this casualty rate. The new Chief of the Imperial General Staff, Sir Henry Wilson, warned him that the War Cabinet would be concerned if he attacked and failed to gain the Hindenburg Line. Lord Milner, the Secretary of State for War, cautioned that there would be no possibility of rebuilding the BEF if it continued to suffer heavy casualties. Haig needed expertly planned and executed attacks by his army commanders to defeat the Germans while still maintaining sufficient manpower for his forces to play their part in the Allied offensive.

The Australian Corps fought as part of the British Fourth Army, commanded by General Sir Henry Rawlinson. Fourth Army was on the right flank of the BEF in the Somme area and occupied a typical frontage of 18,000 to 30,000 yards between the British Third Army on the left and the French First Army on the right. The logistical requirements were massive, with almost 50 trains of supplies a day required when engaged in a defensive fight. Even more would be needed to stockpile ammunition for any offensive. The front was never static, with daily counter-battery and harassing fire, raids and patrols by the infantry and periodic relief of troops from the front line.

An army had a staff of 31 officers and 106 men who planned operations and logistics. The Major General, General Staff, Archibald Montgomery, was the chief of staff and headed the operations section. The General Officer Commanding Royal Artillery (GOCRA), Major General Charles Budworth, was the senior artillery adviser and controlled up to 900 guns and howitzers. Each army had between two and five corps as well as army troops, which were combat and support troops not permanently assigned to any particular corps. The primary army troops were tank brigades, artillery brigades, labour companies, signal units, engineers, and other service troops.

The 5th Royal Air Force (RAF) Brigade comprised army troops consisting of army, corps and balloon wings. The army wing had six or more squadrons of fighters, bombers and reconnaissance aircraft, while the corps wing provided battlefield support such as contact patrols, artillery spotting and reconnaissance. The balloon wing supported each corps with a company for aerial observation. While divisions and corps had their organic, or permanently assigned, artillery the GOCRA had approximately 30 brigades of Army Field Artillery (AFA), Royal Garrison Artillery (RGA) or heavy brigades, and several independent siege batteries available for counter-battery, harassment and general support.

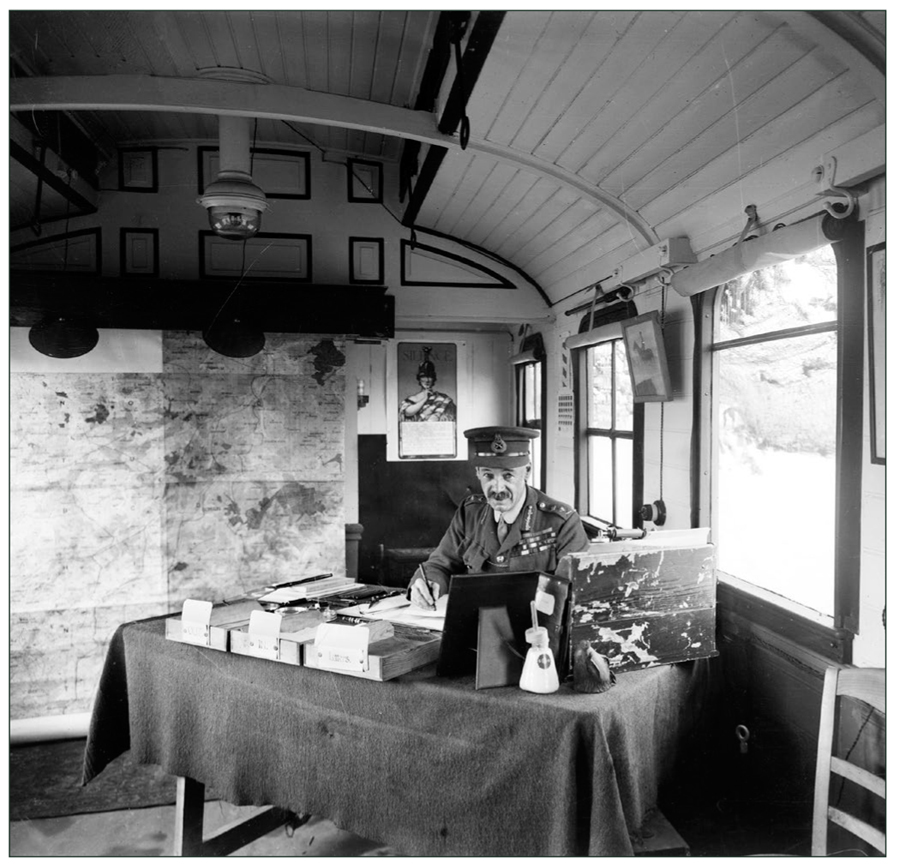

Fourth Army Commander General Sir Henry Rawlinson (AWM E03898).

A corps was commanded by a lieutenant general with a headquarters of 300 men and between two and five divisions and corps troops. Corps troops were similar to army troops but fewer in number, with one RAF squadron, 110 to 120 guns and howitzers, a cavalry regiment, cyclist battalion, and support troops. While corps were important for planning operations and tended to stay in the same area and under the same army, divisions were frequently rotated through corps. The Australian Corps was an exception, and this stability contributed considerably to its fighting prowess. The division was considered the basic tactical unit, as it was the largest fixed formation with all the essential elements to conduct operations.

PRINCIPAL STAFF

| Position | Name |

| Brigadier General, General Staff (BGGS) | Brigadier T. Blamey |

| GOCRA | Brigadier W. Coxen |

| Chief Engineer | Brigadier C. Foott |

| Brigadier General Commanding Corps Heavy Artillery (BGHA) | Brigadier L. Fraser |

| Deputy Adjutant and Quartermaster General | Brigadier R. Carruthers |

CORPS TROOPS

| Unit | Role |

| Australian Corps Signal Company | Corps Communication |

| No. 3 Squadron, AFC | Contact, artillery, reconnaissance patrols |

| Australian Corps Cyclist Battalion | Reconnaissance, escort, dispatch riders |

| 13th Australian Light Horse Regiment | |

| V Heavy Trench Mortar Battery | Indirect fire support |

| Field and heavy artillery brigades | Counter-battery, harassing, general support |

| Tank brigades or battalions | Infantry support |

| Captive Balloon Service | Aerial reconnaissance |

Portrait of Lieutenant General John Monash, General Officer Commanding the Australian Corps (AWM A02697).

THE AUSTRALIAN CORPS

The appointment of Lieutenant General John Monash to command of the Australian Corps on 31 May 1918 was the culmination of a long process of ‘Australianisation’ of the combat formations that Australia contributed to the war effort. Monash and most of the primary staff and commanders were Australian. From August 1918, the five Australian infantry divisions and virtually all of the artillery fought together in the Australian Corps.

Infantry divisions had evolved considerably by 1918, reflecting the new weapons systems and tactics developed during the war. Each division had three brigades of infantry, two brigades of artillery, and divisional troops for a total of 871 officers and 17,350 men. A division was commanded by a major general, supported by 19 staff officers. The Commander Royal Artillery (CRA) was a brigadier who served as the senior artillery commander for the division, while the Commander Royal Engineers was a lieutenant colonel who performed the same function for the engineer field companies and pioneer battalion. By March 1918 the machine-gun companies in each division had been consolidated into a battalion of four companies, each equipped with 16 Vickers guns. At the same time the divisional mortars were reorganised into two batteries of six 6-inch Newton mortars. The divisional heavy mortars were disbanded, with a single battery of six 9.45-inch mortars retained under corps control.

Chart 1. Infantry division

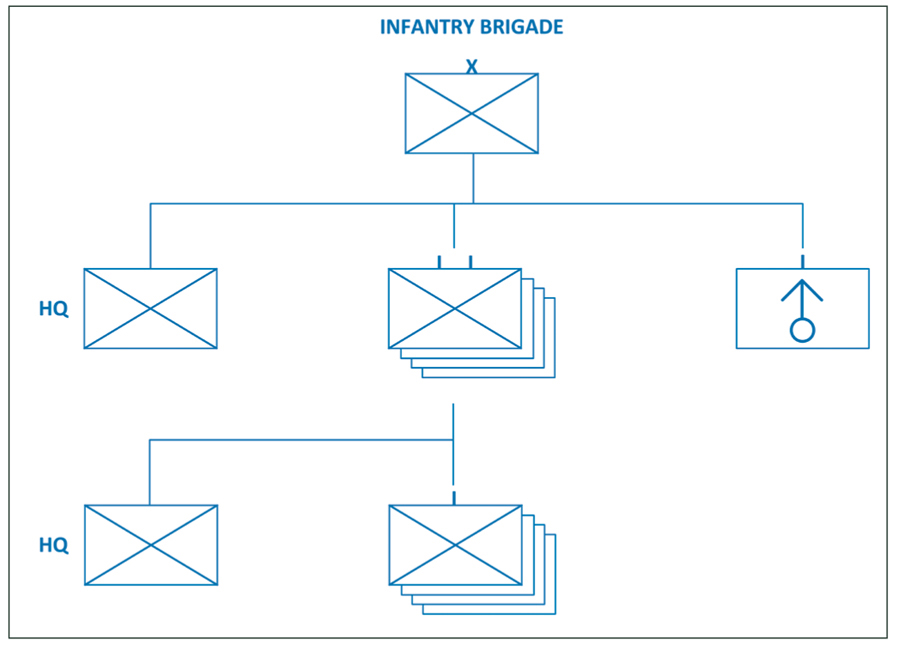

Each infantry brigade had four infantry battalions and a light trench mortar battery of eight Stokes mortars for an establishment strength of 191 officers and 3679 men.

Chart 2. Infantry brigade

The Australian Corps suffered over 45,000 casualties from March to September 1918 and experienced difficulties keeping its units up to strength. In February the British disbanded the fourth battalion in each infantry brigade to bring the remainder closer to establishment strength. The Australians resisted this, but disbanded the 36th, 47th and 52nd battalions after the fighting in April and May. On 31 August 1918 the infantry battalions in the Australian Corps averaged 653 men.

The infantry battalions had been reorganised in June and July 1918 with a reduction to 44 officers and 901 men in four companies. A full-strength company of 187 men had four platoons. There was usually one Lewis gun section with two guns, and two rifle sections in each platoon, for a strength of between 28 and 40 men. Each battalion had 32 Lewis guns, and 50% of riflemen were trained in bombs or rifle grenades. Tactical experimentation showed that one non-commissioned officer (NCO) and six men for a rifle section and one NCO and 10 men for a Lewis gun section was the minimum number required for effective small-unit tactics.

Infantry battalions never brought their full strength into combat. A proportion of men were sick, on leave, completing courses or employed elsewhere. There was also a ‘left out of battle’ cadre or nucleus that would be used to rebuild the battalion if it suffered heavy casualties. The logistical portions of the companies and battalions were not considered fighting troops. With these deductions, a full-strength battalion brought 708 men and 20 officers into action, or approximately 159 per company, with 72 men at battalion headquarters. This was known as the trench strength of the battalion. In September 1918, trench strengths were between 300 and 400 men, including 20 officers.

WEAPONS SYSTEMS

The war spurred tremendous advances in technology. By 1918 many new weapons had been developed and forces equipped, and even those still in use from 1914 had often been upgraded to increase their range and destructive power, and enhance their combat effectiveness.

The 1918 infantry platoon was equipped with the Lee-Enfield rifle, the Lewis gun and the No. 23 and No. 36 Mark 1 grenades. Typically, around four men per platoon had cup dispensers to fire rifle grenades, and a platoon might carry as many as 100 grenades.

Although mortars represented a well-developed weapon, they had fallen into disuse prior to 1914. Trench warfare and the need for high-angle fire led to the development of three types of mortars. Light mortars, such as the 3-inch Stokes mortar, were crewed by infantry and operated in direct support of front-line battalions. However, they required large carrying parties to be effective. Medium and heavy mortars were crewed by artillery personnel and were divisional and corps troops that were given distinct roles within artillery plans. Light mortars were used as anti-personnel weapons and against lightly fortified areas. Medium and heavy mortars were employed against fortified dugouts and emplacements as their greater projectile weight provided more destructive effect.

Short Magazine Lee-Enfield Rifle, Mark III* (AWM REL24793).

The Lee-Enfield was a bolt-action rifle with a 10-round magazine that fired a .303-inch cartridge to an effective range of 550 yards, though 300-400 yards was much more realistic for the average soldier. Most engagements were fought within 200 yards. The typical rate of fire was around five rounds per minute. The rifle was equipped with the Pattern 1907 bayonet.

No. 36 Mark 1 Grenade (AWM RELAWM02093).

No. 23 Mark 2 Grenade (AWM REL34881).

The No. 23 and No. 36 Mark 1 grenades were thrown or fired from a cup dispenser attached to the Lee-Enfield rifle. The 1.7lb grenade had a thrown range of up to 20 yards for a novice and 40 for trained bombers. The rifle grenade’s maximum range was approximately 210 yards, but the effective combat range was 100 yards. The grenades had a blast radius of 7 yards and fragmentation radius of 75 yards. Grenades could cover dead space and were effective against concrete strongpoints.

The Lewis .303-inch Machine-gun, Mark 1 (AWM REL/10285).

The Lewis gun, introduced in 1915, was an air-cooled, gas-operated light machine-gun. The rate of fire was 100 rounds per minute with a 47-round magazine and an effective range of 500 to 880 yards. The 28lb gun could be fired by one man, but was normally operated by a crew of two with three to five scouts carrying up to 30 magazines per gun.

A VICKERS MACHINE -GUN MARK 1.

The Vickers machine-gun Mark I was a water-cooled, tripod-mounted machine-gun that fired the .303 cartridge with a range of 2000 yards for direct fire and almost 4500 yards for barrage fire. The Vickers gun required a crew of six to bring the 42.5lb gun and 48lb tripod into action. The nominal rate of fire was 500 rounds per minute using 250-round cloth belts.

A Vickers gun team from the 24th Machine Gun Company (AWM E03268).

Table 1. Mortar characteristics

A Stokes mortar crew in action (AWM E02677).

ARTILLERY

Artillery saw exponential growth in numbers of pieces, range, destructive effect and sophistication in organisation and employment. In offensive operations, artillery fulfilled two crucial roles: the neutralisation of enemy direct fire weapons by barrage fire, and the neutralisation of enemy artillery fire through coordinated counter-battery efforts. These two roles, if properly coordinated, enabled the infantry to employ its own weapons systems along with tank support to attack strongly held positions with a reasonable chance of success.

In 1918 the BEF utilised two types of artillery: field artillery for barrage fire and general support, and heavy artillery for counter-battery, interdiction, harassing fire and attacks against strongpoints. Artillery consisted of howitzers — which fired a heavier projectile at a low velocity, but high angle of trajectory — and guns, which fired a lighter shell at a higher velocity on a flat trajectory. The basic unit of employment for field artillery was the brigade, which consisted of four batteries commanded by a lieutenant colonel. The number of guns per battery was fixed at six for lighter pieces, and varied with larger guns and howitzers, but was usually between four and six.

Historian Garth Pratten notes that artillery was organised into three tiers of support — divisional, corps and army — based on capability and mobility. Divisional artillery consisted of the two artillery brigades organic to each infantry division under the overall supervision of the CRA. Each brigade had three batteries of 18-pounder field guns and one of 4.5-inch howitzers. In deliberate attacks, a CRA often controlled several brigades of artillery fire for the barrage and other infantry support, under the direction of the Corps GOCRA. Corps artillery employed heavier pieces under the GOCRA and BGHA for counter-battery, harassing and interdiction fire within the corps zone. Army artillery, either under the GOCRA or delegated to corps, controlled the heaviest and least mobile pieces, such as those on railway mountings, and were used for long-range counter-battery fire and against operational and strategic targets. The Australian Corps had 10 divisional artillery brigades, two for each division, and three AFA brigades, which were held at corps level and assigned to divisions as required. These brigades were all manned by Australian personnel. However, the Australian Corps also had several British AFA and RGA brigades assigned to fulfil the artillery role.

Table 2. Artillery characteristics

The primary divisional artillery pieces of 1918 were the 18-pounder gun and the 4.5-inch howitzer. Both weapons were towed by a limber and team of six horses. Each gun had a detachment of 10 and was capable of firing high explosive (HE), shrapnel, smoke, and gas rounds. The 18-pounder had a calibre of 3.3 inches and fired an 18.5lb shell up to 6525 yards. The 4.5-inch howitzer had a calibre of 4.5 inches and fired a 35lb shell up to 7300 yards. For planning purposes 90% of the theoretical maximum range was often used to account for variability in conditions of the guns and weather. Divisional artillery was generally emplaced to provide coverage up to 3500 yards ahead of the front line, which dictated initial objectives in attacks.

18-pounder Mark I (AWM E01208).

QF 4.5-inch Howitzer Mark II.

Mark V* tank (AWM E05426).

First used during the Battle of the Somme in 1916, the primary tanks in the Hindenburg Line campaign were the Mark V and Mark V* heavy tanks and the Medium A or Whippet tank. The Mark V had male variants that mounted 6-pounder guns and female variants that carried machine-guns. The Mark V* was a variant of the Mark V with increased length to cross wider trenches and carried supplies or up to a section of troops.

Tanks were organised into sections of four, with heavy tank companies comprising four sections: three fighting and one reserve. Battalions had three companies and tank brigades had three battalions.

Table 3. Tank characteristics

AIRCRAFT

No. 3 Squadron, AFC, was the corps squadron for the Australian Corps and was equipped with the Royal Aircraft Factory RE8. The RE8 was a two-seater biplane with a 150-horsepower engine, a top speed of approximately 103 miles per hour and endurance of 4.5 hours. Armament consisted of one forward-firing Vickers machine-gun and a Lewis gun on a Scarff ring mount for the observer, with bomb racks under the lower wings capable of fitting two 112lb bombs. The aircraft could be equipped with cameras for photographic reconnaissance. The squadron was divided into three flights totalling 18 aircraft.

The main function of the corps squadron was to assist the artillery and infantry through aerial reconnaissance, spotting and contact patrols. The squadron assisted in counter-battery work by detecting hostile batteries and observing friendly artillery fire, as well as initiating zone calls for enemy targets spotted. Reconnaissance photos generated the updated maps that both infantry and artillery depended on for planning, while contact patrols were devised to allow formation commanders to follow the progress of attacks. The squadron sent aircraft over the attack route, sounding klaxon horns to signal the infantry to fire flares or show identification to enable the aircraft to find the front line. At Hamel in July 1918, aerial resupply was trialled and incorporated into future attacks, though tank and infantry supply remained the main forms of replenishment. Large attacks were also supported by the army wing of the 5th Brigade, RAF, which prevented German aircraft supporting their ground troops, conducted attack missions on enemy staging areas, and provided close air support for Allied troops.

AUSTRALIAN CORPS: TRAINING AND TACTICS

A key factor in the Australian Corps’ success in 1918 was the practical implementation of combined-arms tactics, which meant that infantry, artillery, tanks, aircraft, engineers and support troops worked together to achieve a better result than was possible through independent action. The key factor in this synergy was identifying deficiencies in battlefield performance. While new weapons systems were developed to address these shortcomings, they required training, organisation and new tactics to become effective. This was a continuous cycle implemented by veteran troops to increase combat efficiency.

Many popular accounts of the First World War portray Australians as natural fighters and argued that they were superior to their British counterparts because they came from a rural, decentralised society. C.E.W. Bean asserted that this made Australians ‘half a soldier’ even before they enlisted. Historian Robert Stevenson’s study of the 1st Division refutes the ‘natural soldier’ theory by demonstrating that, by 1917, Australian Imperial Force (AIF) recruits received initial instruction in Australian camps and then at least 14 weeks of training in Britain and France before they joined their units. Specialist training continued even after a recruit reached the front line. For example, the 1st Division spent almost 20% of its time in training and, even in the line, leaders at all levels conducted informal unit drills to integrate new recruits, cross-train on weapons systems, incorporate new tactics, and develop new methods of fire and manoeuvre. The uniformity of the Australian Corps was a product of this training culture, as lessons were shared across the units, ensuring a high degree of interoperability and uniformity.

OFFENSIVE TACTICS

Although severely challenged by the defensive firepower of artillery and machine- guns, the infantry remained the decisive arm of battle in 1918. No-one else could take and hold ground and, while tanks were promising, their inherent unreliability and limited endurance meant that they supported rather than supplanted the infantry. Synergy of infantry, artillery, tanks, mortars and machine-guns led to a reliable method of ‘breaking in’ to enemy defences rather than ‘breaking through’ the line. Historians Robin Prior and Trevor Wilson argue that this weapons system was a vital factor in the success of the British, but that it was limited to the supporting range of artillery. Short-ranged offensives with pauses to consolidate — the ‘bite and hold’ battle — were the key to victory.

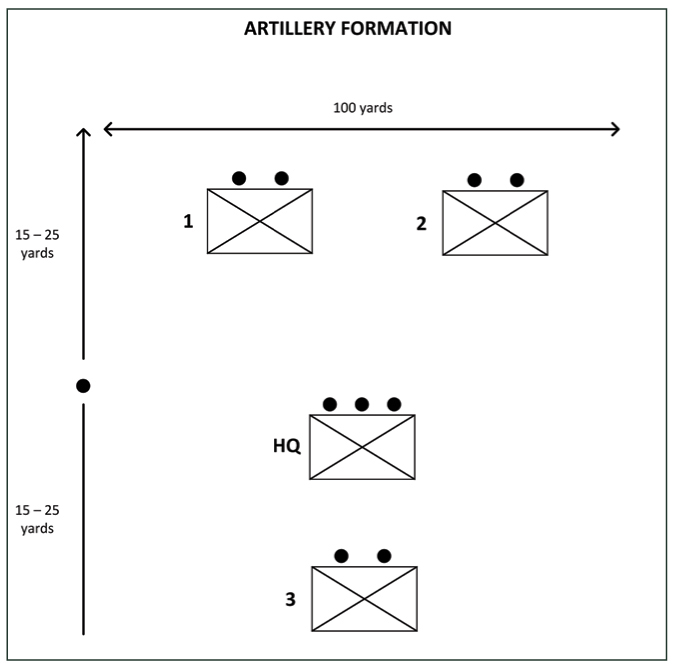

Two main theories of control dominated tactical experimentation. Decentralised control pushed responsibility down the chain of command, while centralised control integrated more and more units at higher levels. Both of these were used to achieve greater flexibility in conducting offensive operations. The key limitation in command and control was communication. While contact could be maintained from the front lines rearward, when units attacked, it became much more difficult to follow the battle. For the infantry, the basic unit of manoeuvre devolved from the battalion down to the platoon and section. The platoon was the lowest element equipped with all the basic infantry weapons (Lewis guns, rifles and grenades) necessary to achieve objectives. Formations loosened up, the density of attacking troops diminishing as a consequence. When approaching the front line, units adopted artillery formation, which maintained control but minimised the target profile.

The infantry was increasingly task rather than terrain oriented, and was assigned fewer objectives, relying on reserves to ‘leapfrog’ through and attack the next objective. Formations could now attack further into the enemy’s lines. When supported by artillery, the leading wave kept pace with the barrage. The second and third wave mopped up, a task defined as ‘the killing or disarming of all enemy found in hiding, the picketing of the entrances and exits of all dugouts, and laying siege to them until their occupants surrendered.’ Vickers guns were often attached to attacking battalions to provide additional fire support and were extremely useful in consolidating newly won positions. In open warfare, platoons and companies adopted a mix of diamond and line formations depending on the terrain.

Chart 3. Platoon artillery formation

Platoons were too small to engage in major attacks, as were companies and battalions. The division remained the basic tactical unit, but the brigade was the key bridge between the two. Attacking brigades usually received divisional assets to become combined-arms groups. In turn, they passed these weapons systems to their battalions to achieve defined objectives on a frontage of 800 to 1500 yards.

Chart 4. Platoon attack formation

Pattern 1908 Web Equipment (AWM RELAWM07759.001).

The equipment carried into battle often weighed as much as 60 to 80 pounds and included individual weapons, rations, and unit gear shared among the men. The equipment varied for each operation, depending on the task. The following equipment was carried by the 30th Battalion on 29 September:

Each soldier:

Rifle with 170 rounds ammunition, bayonet and oil bottle, web equipment

Small Box Respirator with metal discs

2 full water bottles, 48 hours’ iron rations, greatcoat and waterproof ground sheet.

Platoon gear:

Ground flares – 14 per platoon

No. 27 grenade (white phosphorous) – 6 per platoon

No. 36 grenade – 12 per platoon

SOS Rockets – 5 per company

Success signals – 8 per company

Lewis gun magazines – 20 per gun

Wirecutters, grenade discharger cups – 2 per platoon

Privates George James Giles and John Wallace Anderson in fighting order (AWM E02818).

Artillery evolved from destructive fire in 1915 and 1916 to neutralisation fire in 1918. Improvements in surveying, meteorological data, calibration, sound ranging and flash spotting, ammunition quality and aerial reconnaissance meant that predicted fire from maps was far more accurate. Innovations such as the 106 fuze for HE shells, which made them much more effective than shrapnel at cutting wire, and the increased use of gas shells for counter-battery, harassing and area denial fire meant that preliminary bombardments were generally no longer required. A creeping barrage, accompanied by counter-battery fire, neutralised defenders by forcing them to remain in their dugouts until the attackers were upon them. Enemy gunners were killed or driven away from their artillery for the duration of the attack. To achieve this, artillery was coordinated at the corps and army levels for zone calls and the deep battle, and under one or more CRAs for barrages and infantry support. A specialist counter-battery staff officer (CBSO) at corps level handled all counter-battery fire and worked to silence enemy batteries.

The basic infantry support was the creeping barrage. The artillery fired HE and shrapnel shells in lines parallel to the infantry line of advance and lifted them at set intervals to enable the infantry to move forward. After Hamel, the Australian Corps incorporated smoke into the barrage to isolate the battlefield and hinder the defenders’ visibility. The exact details of each barrage varied according to terrain, enemy defences and weather. Infantry troops formed up on their jumping-off tape while they waited for the barrage. The nearest line would begin 200 yards in the direction of the advance and hold for a number of minutes, then advance at a predetermined rate, usually three to four minutes per hundred-yard lift. The barrage would continue, sometimes pausing beyond objective points to allow the infantry to consolidate. At the furthest point the barrage became a protective fire beyond the final objective and helped break up counter-attacks. There was always overlapping coverage, and 4.5-inch howitzers usually traced a barrage line in front of the 18-pounders. Machine-gun barrages were often incorporated to ‘pinch’ the Germans between their fire and the artillery. While creeping barrages limited the mobility of the infantry, attacking without a barrage carried a much higher risk of failure. Heavy artillery was generally not used within 600 yards of friendly troops, but designated bombardment brigades fired ahead of the field artillery at specified targets within zones, the fire lifting along with the rest of the barrage.

Troops of the 45th Battalion advance behind a creeping barrage near Le Verguier (AWM E03248).

The new development in the infantry-artillery attack was the tank. The Mark V and Mark V* were reliable enough for mass tank attacks in support of infantry. Monash specified an ideal ratio of one tank per infantry company to ensure support. Each tank had one task so that, if it were knocked out, follow-on waves would not be affected. Tank tactics stressed the importance of coordination with the infantry, which necessitated prior training and rehearsals. Tanks were effective in creating lanes in wire by crushing them and, if protected by infantry, at destroying machine-gun nests and other strongpoints. Supply tanks acquired a defined role in bringing up ammunition and evacuating wounded, proving particularly valuable as infantry battalion sizes dwindled.

Tanks were limited by their endurance and mobility; their availability dropped sharply after the first day of battle as a proportion of tanks ‘ditched’ or were stuck in shell holes and obstructed by uneven terrain. Small numbers and open terrain increased their vulnerability to artillery fire. Tank communications were still primitive, relying on visual signalling at the tank-infantry level. Training with the infantry was essential to gain the most effective cooperation, but was not always possible. All of these factors meant that tanks were an addition to the infantry-artillery battle, but not their replacement.

While the combination of tanks, artillery, infantry, machine-guns and aircraft was potent and a potentially effective weapons system, it was also a fragile one. Any failure by a single supporting arm could jeopardise an entire attack. Adverse weather such as rain, fog or limited visibility dramatically reduced the effectiveness of aerial, artillery and armoured assets. Communications below the divisional level depended primarily on wire, were fragile, and inevitably lagged behind the advance. Below battalion level, visual signalling and runners predominated. A delay of an hour for a response to brigade from battalion, or 90 minutes if a tactical matter needed to be referred to division, was not uncommon, and sometimes messages could arrive out of sequence or with widely varying delays. By mid-1918 some progress had been made with standardised methods of establishing communication and the introduction of more reliable equipment, including wireless. Secrecy was an important factor, as a counter-preparation barrage by the Germans on assembly areas and troop concentrations could completely derail an attack. Failure to coordinate between units or weapons meant gaps for the enemy to exploit. These risks could be minimised by effective staff work, but not eliminated, and all played a role in the attacks on the Hindenburg Line system.

STAFF AND BATTLE PROCEDURES

The staff of the Australian Corps played a crucial role in the Hindenburg Line campaign. They turned the commander’s directives into a synchronised plan that integrated weapons systems and tactics. Formal staff officers existed in formations down to brigade, and in the Australian Corps these were almost without exception staffed by officers who had seen extensive front-line service. In the brigade, the brigade major and staff captain planned operations and logistics respectively. Divisions had 19 staff appointments, responsible for operational, administrative and logistical matters, as well as specialist staff such as the artillery and engineer advisers. Corps staffs were much larger; as operations became more complex, planners projected two battles ahead to ensure that sufficient combat strength existed to fulfil their mission. Artillery staff at corps level such as the GOCRA, BGHA and CBSO assumed planning and limited command authority for guns in the corps.

A well-known quote in Monash’s memoirs of 1918 draws a comparison between a battle plan and an orchestral score:

A perfected modern battle plan is like nothing so much as a score for an orchestral composition, where the various arms and units are the instruments, and the tasks they perform are their respective musical phrases.

Historian Peter Pedersen’s analysis of mission planning in the Australian Corps in 1918 illustrates how the staff used battle procedures to implement this orchestration. Battle procedures consisted of four stages: warning orders, mission planning, operations orders, and movement. The warning order was an initial notice of attack that allowed subordinate units to begin their preparation. Mission planning worked out the details of the attack, including objectives, synchronisation of zero hour with flanking units, use of artillery and air support, and the necessary logistical details. Once the plan was finalised, units sent out formal operations orders that described in detail what they were required to do. Movement by subordinate units occurred throughout the planning phases as necessary. As corps and divisions worked through the procedures, their subordinate units gained the information needed to conduct their own planning. Different units would therefore be at different stages of battle procedures at any given time, but were fully coordinated and ready to assault at zero hour. Ideally, final orders were to reach brigades no later than 36 hours before zero, but this was impossible after the first day of an offensive.

The BEF and Australian Corps developed new organisations, equipment and tactics over four years of war and were now on the strategic offensive. However, their German opponents had substantial experience on the defensive and had developed new doctrines of their own. This would be no easy fight.