10. After the Wall: Capitalism BAE-Style

Vienna’s first district retains much of the Hapsburg city’s imperial grandeur. At its centre lies the Ring Straße, encircled by imposing facades and regal statues of Emperor Franz Josef. It exudes aristocratic power and wealth. 14 Kärtner Ring is nestled between Belvedere Palace in its baroque splendour, the Musikverein, which has been home to some of the world’s greatest classical musicians, and the ultra-luxurious Hotel Imperial. The building’s cavernous vestibule leads to a grand staircase. On the first floor an innocuous small white door bears the large black letters ‘MPA’ on a brass background, underscored with the name ‘Mensdorff-Pouilly’.

The interior reflects its surroundings: ornate high ceilings, deep, aged leather chairs, expansive canvasses of demure young noblewomen alongside the stuffed heads of animals vanquished on the rural hunting estates of the aristocratic tenant. A severe assistant greets me and tells me she will inform the Count I am here.

Count Alfons Mensdorff-Pouilly, ‘Ali’ to his innumerable friends, is taller, thinner and more handsome than he appears in pictures. He is of imposing height and aristocratic bearing in a green baize alpine jacket and somewhat audacious pink tie. He is charming in a slightly roguish way. As we lower ourselves onto the sumptuous leather, the austere Magister Luka perched beside me blinking at her poised notebook, the 56-year-old bon vivant cuts through my awkwardness at asking inconvenient questions about his career as BAE’s most notorious agent in Eastern and Central Europe, by regaling me with stories of his two brief spells in jail.

‘Five weeks in an Austrian jail was far easier than five days in a British prison. I couldn’t get anything from the British authorities, not a toothbrush, a comb, nothing. I befriended all the prisoners,’ he says with a hint of macho pride, ‘and a black man offered me his comb and toothbrush. I washed and used the comb, but I couldn’t use the toothbrush.’1 After his spell in Pentonville prison, north London, Mensdorff-Pouilly complained that his human rights had been abused because his prison underpants were too small.2 ‘I wasn’t given decent underwear despite having asked for it several times.’3

He describes MPA as a consulting company through which he provides strategic advice about Central and Eastern Europe to between thirty and forty clients in a variety of sectors, mainly healthcare. He claims that BAE was his only client in the defence industry. He came into contact with the British company through the husband of a cousin, Tim Landon. A notorious character, Landon was known as ‘the White Sultan’ for his close links to Oman, where he assisted in a coup in which his friend from Sandhurst, Sultan Qaboos bin Said, overthrew his father. Landon made hundreds of millions of dollars out of his business dealings with Qaboos. He earned his early money breaking the oil embargoes of South Africa and Rhodesia and smuggling Bofors cannons to Oman in the 1980s.4

Mensdorff-Pouilly speaks with fondness of Landon, who died in 2007. He explains that Landon had told BAE that to win business in Central and Eastern Europe they needed somebody who was well-connected in the region. Landon introduced them to the Count, who claims to know everybody who is anybody in Austria, the Czech Republic and Hungary, the former Austro-Hungarian Empire of his aristocratic lineage – he even claims a cousin related to Queen Victoria. Mensdorff-Pouilly, who is married to Maria Rauch-Kallat, a former Austrian Cabinet minister and a senior member of the conservative ÖVP, says he can talk to all the key politicians in the region whenever he wants to. He contends that he was always paid by BAE on a monthly retainer for his political and economic insights into these countries.5

The authorities argue that in the late 1990s BAE made payments of more than £19m to companies associated with the Count, most of which were connected to ‘solicitation, promotion or otherwise to secure the conclusion of the leases of Gripen fighter jets to Hungary and the Czech Republic.… BAE made these payments even though there was a high probability that part of the payments would be used in the tender process to favour BAE.’6 Put more explicitly by a UK court: ‘BAE adopted and deployed corrupt practices to obtain lucrative contracts of jet fighters in Central Europe.’ The barrister Tom Forster described the company’s activities as ‘a sophisticated and meticulously planned operation involving very senior BAE executives … [who] spent over £10m to fund a bribery campaign in Austria, the Czech Republic and Hungary’.7 Three offshore entities were created in Switzerland to prevent them ‘being penetrated by law enforcement’ agencies, with ‘the underlying purpose to channel money to public officials’.8 About 70 per cent of the BAE money transferred to Mensdorff-Pouilly went into accounts in Austria.9 There were ‘significant cash withdrawals’, often within days or weeks of important defence procurement decisions. BAE executives were alleged to be present at meetings where ‘so-called third party payments or down-the-line payments’ were discussed.10

More than £19m was transferred to the Count, but all he officially did in return was produce his ‘marketing reports’.

Havel’s Nightmare

Vaclav Havel, Czechoslovakia’s remarkable dissident playwright turned President, suggests that ‘politics is work of a kind that requires especially pure people, because it is especially easy to become morally tainted’.11 BAE tested this maxim to the limit.

The Czech Republic, as it became after the split with Slovakia in 1993, joined NATO in 1999, necessitating an upgrade in military equipment. That year, companies were invited to submit proposals for the purchase of fighter aircraft. Five companies tendered bids, including Saab, which had entered into a deal with BAE in 1995 to help with the marketing of the Gripen aircraft. The Gripen had recently suffered severe setbacks with a dramatic accident during testing and another crash during the Stockholm Water Festival before tens of thousands of spectators.12

From 1997, the partnership started an intensive campaign to persuade the Czech government to buy the plane. It was primarily run by two BAE men, Steve Mead and Julian Scopes. Eventually, in December 2001, the government resolved to buy twenty-four Gripens for a price of approximately £1bn. All four of the other competitors withdrew from the competition, alleging corruption in the process.13 The deal met with substantial resistance in both houses of the Czech parliament, where it was narrowly voted down.

The summer of 2002 brought devastating floods to the Czech Republic and the election of a new government, putting the Gripen purchase on hold. The costly clean-up from the natural disaster and the excessive cost of the new fighter aircraft led to the creation of an ‘expert committee’ to resolve the tender.14 At the time, the UK offered to provide fourteen used Tornado jets as a stop-gap measure while another tender could be organized for the aircraft purchase. (Though it was reported as a free offer, it is likely that BAE would have profited from the provision of training and spare parts.15) Tony Blair made a very public lobbying visit to the country in 2002 as part of the BAE/Saab campaign.16 The committee, however, decided on a ten-year lease of fourteen Gripens for £400m, without a public tender. The deal was signed in June 2004, immediately reigniting allegations of corruption.17

After the US Defense Department, along with the contractors Lockheed and Boeing, had withdrawn from the competition, the US government accused BAE and the British government of ‘corrupt practice’ in a meeting with Sir Kevin Tebbit, the Permanent Secretary at the Ministry of Defence.18 During the meeting US officials ‘underscored our concern about persistent allegations that BAE Systems pays bribes to foreign public officials to obtain business’.19 They also ‘emphasize[d] a consistent pattern of alleged behaviour, over time. Press accounts reinforce material from more sensitive sources.’20 They asked what the British government had done to investigate allegations of bribery by BAE, not only in connection with recent projects, but also older ones ‘for which bribe payments may still be ongoing’.21 They suggested that ‘in the US, this volume of allegations about one company would have triggered a Department of Justice Criminal Division investigation long ago’.22

American officials nicknamed Tebbit ‘Sir Topham Hatt’, after the Thomas the Tank Engine character, because of what they described as ‘his almost haughty disdain for the allegations of bribery involving BAE’ and the orotund manner in which he challenged them to detail evidence of wrongdoing.23

Tebbit may have been feigning ignorance because the Czech police had already confirmed attempts by BAE to corrupt Czech politicians.24 Two senior opposition MPs separately reported efforts to bribe them and their parties to vote in favour of the Gripen when the deal originally came before Parliament. Jitka Sietlova, an opposition Senator, recounted: ‘I was contacted by an acquaintance who told me it would be to my advantage if I voted for the Gripen project. I reacted negatively, you don’t do things like that, I was dismayed that someone thought you would do something like that.’25 The other politician, Premysl Sobotka, described how ‘there were strangers who approached me in the street. They said that if I voted in favour, they would make investments in my constituency. I refused to speak with them, I don’t like that.’26 A third, Michael Zantovsky, also had an offer by telephone, of SEK10m to his party. Zantovsky and the other seven Senators in the ODA party, of which he was leader, did not vote against the Gripen. But he did go to the police, who traced the call to a telephone booth just outside a government building, a stone’s throw from the Senate. The police investigation concluded that a crime had been committed but closed the case six months later after failing to identify the caller.27

The promised investment in Sobotka’s constituency probably referred to the offset investments, which were a crucial element of the BAE/Saab campaign to sell the Gripen. On the original deal to sell twenty-four of the aircraft, contracts worth 150 per cent of the cost were to be placed with Czech companies.28 The generosity of the offsets was put forward as one of the most important reasons for buying the Gripens. The offset programme for the lease deal was similarly extravagant and much larger than any competitors, at $950m, approximately 130 per cent of the value of the aircraft.29 However, the offset contracts incorporated a confidentiality agreement that veiled any actual economic activity in mystery. Only the company was able to reveal details of the promised investment. So they claimed that the programme was to be directed at regions with high unemployment, including north Bohemia – slated to receive 38 per cent of total offset investment – and north Moravia, which was to reap 33 per cent.30 By mid-2005, senior representatives of the north Bohemian and north Moravian regions said they had no information about offset projects. ‘Lots of promises have been made public, but I’m not aware of any offset project so far.… I was always rather sceptical about the offset program,’ said Evzen Tosenovsky, Governor of the Moravia–Silesia region, which had an unemployment rate of 14.5 per cent at the time.31 According to the Trade and Industry Minister, Milan Urban, sixteen projects had been identified and ‘some of them are already running’, though he refused to elaborate.32 Opposition politicians raised concerns about why the offsets would be kept secret and why representatives of the regions involved would not know about the supposed investment in their area. Even the head of the Armaments Industry Association seemed confused: ‘That’s not sensitive data that needs to be classified.’33

The true nature of the deal was exposed when journalists from Swedish Television, Sven Bergman, Joachim Dyfvermark and Fredrik Laurin, tracked down an anonymous whistle-blower involved in the BAE sales campaign and a host of secret documents obtained from the Czech police investigation. The anonymous source told them:

Everyone wanted to achieve so much, the project was so important, we just got carried away … But after I stopped going to corrupt Prague I realized it was all wrong, very wrong.… The Gripen campaign had a huge exclusive office on the heights of Prague, with a view over the whole town. Steve Mead’s room was in the inner part of the office. There was a desk, a couple of chairs, and on the wall a board. Steve Mead surveyed Czech politicians. On the board there was something like 50–100 pictures. Photos of members of the government, key people in the parliament, senators, members of the opposition, and other important people, for example from the Ministry of Defence. There were names and positions and handwritten details of each person, and most of them were marked; green, amber or red – for, in between, or against the Gripen.34

When the journalists visited the plush offices the landlord confirmed that BAE were the previous tenants. The keys were still labelled with the name of the company. The landlord told them excitedly that in the ‘particularly fine room’ that belonged to Steve Mead ‘He has boards, with pictures of all members of government and House of Deputies. Because it was the biggest business in new Czech history.’35

The whistle-blower continued: ‘The most important object was Ivo Svoboda, who, at that time, was the Finance Minister. Mead also spoke of the importance of taking care of the opposition in the same way. They worked on key people, who were to enrol the other party members later.’36 Svoboda was forced to resign in 1999 over an unrelated fraud scandal and was sentenced to five years in prison. The source explained what happened then: ‘When Svoboda went to prison, Mead was forced to rearrange the deal and the contacts were then handled by another member of the government.’37 It was clear that the matter at hand was bribes: ‘Steve Mead spoke of the contact in Austria that took care of the payments for the Czech government. He was responsible for the payments, paying the bribes. The Austrian contact could distribute the money to those in the government who were not already “onboard”, and also to those who were already on our side. It was enough to focus on a few key people in the government to get approval to pass the decision.’38

The secret agency agreements for the deal confirmed the corrupt behaviour and the identity of the Austrian contact. The first was a contract from BAE:

In Strict Confidence

Proposal: appointment of advisor

Date: 5 November 1999

Territory: Czech Republic

Products to be included in the agreement: Gripen

Name of advisor: Alfons Mensdorff Pouilly

Address of advisor: MPA Vienna39

The journalists recognized the Count’s name from another BAE scandal. In 1995, he was identified on a tape recording as the conduit for secret payments from BAE to party funds in Austria in return for the sale of aircraft. If the deal was concluded the two political parties stood to share 70m Schillings ($7m in 1995 or £4.4m). The secret tape contained the following conversation:

Herman Kraft: (an Austrian ÖVP MP) A few hundred million for the plane and a few billion for the helicopters.

SD: (An unidentified Social Democrat MP) How much are we talking about?

HK: Two Percent.

SD: Two Percent of 3 billion?

HK: 3.8 billion

SD: Two percent is 70 million. How would it be shared?

HK: We split it

SD: Who will transfer the money?

HK: Our Count.

SD: What’s his name?

HK: Mensdorff.

SD: That’s his name, Mensdorff? And he represents the English?

HK: He’s their consultant

SD: How will the money get to Austria?

HK: The English will fix that.40

Herman Kraft was convicted for attempted bribery, but Mensdorff-Pouilly was acquitted as the reference to him was not considered sufficient evidence. Both BAE and the Count denied any involvement.41

In relation to the Czech aircraft deal there was also a secret agreement promising Mensdorff-Pouilly a massive commission if the deal went through. It identified the contract value as up to £1bn with a commission rate of 4 per cent.42 This would have worked out to £40m, an extraordinary sum for any legitimate help a local adviser might provide. Mensdorff-Pouilly refused to speak to Swedish TV but admitted to the Guardian that ‘my company, MPA, has a contract with BAE since 1992 for consultancy services in Eastern Europe. According to this contract I’m paid on a monthly basis.’43

However, he was not the only agent. At the bottom of the contract was a sentence reading: ‘Details of other representatives in the same territory: Hava.’44 Richard Hava was the director of the Czech state arms company, Omnipol, in which BAE had bought a stake in 2003.45 Omnipol was to be used openly by BAE in their Gripen campaign but a further covert agreement revealed more:

BUSINESS SECRET

Region: Czech republic

Concerns: Gripen programme

Agent: Richard Hava

c/o Legal Advisor Remo Teroni, Geneva

Estimated contract value: £1.5 billion

Commission: 2%46

This implies that Hava would be paid up to £30m if the Czechs bought the Gripen. Interestingly, Hava’s address is not given as Omnipol. He was allegedly to be paid via an entity called Gabstar.47 Hava denied any role, telling Swedish TV: ‘I am not a secret agent, not now, not before.’48

Hava’s agreement, in turn, contained the name of yet another agent: ‘Additional representatives in region: Jelinek.’49 Otto Jelinek is a former world champion figure skater and Ice Capades star turned politician. He became a minister in Brian Mulroney’s Tory government in Canada before returning to his native Czech Republic, where he became well-known in business circles. Jelinek admitted to having BAE as a client: ‘British Aerospace was one of numerous clients that I had.’50

Jelinek and the other agents were paid through offshore accounts in BAE’s usual intricate manner. The company made payments via Red Diamond’s account at Harris Bank in New York to Jelinek International and Dubovy Mlyn, companies controlled by Jelinek. He was also paid via a Bahamian entity called Fidra Holdings.51 Additional money was sent from Harris Bank to another Bahamian entity called Manor Holding, a company Jelinek was said to represent.52 When asked about the payments through the offshore companies Jelinek responded: ‘It is personal, like my sex life.’53

There is no doubt though that Mensdorff-Pouilly was the primary agent, responsible for disbursing money. While the arrangements for the leasing deal that actually eventuated may have differed from the earlier attempt to sell the Gripens they are just as damning. They document a series of payments from Tim Landon’s company, Valurex, to Mensdorff-Pouilly, who then distributed some of the money onwards. (See p. 206.)

Valurex paid Mensdorff-Pouilly as a consultant. He then made payments using another British Virgin Islands entity, Brodman Business, whose managing director had been a friend of the Count’s since school. Brodman was used as a hub for the payments received from Landon from 2002 until his death in 2007.55 Money was paid out through ‘significant cash withdrawals, often in the range of 100,000 pounds, often within days or weeks after important decisions of military procurement, in which BAE had a strong interest’.56 Mensdorff-Pouilly described Brodman as a mechanism to spread his investment capital, though it seems a fiendishly complicated investment scheme. As always, he claims the payments were for ‘marketing reports’, which consisted of ‘a compilation of newspaper clippings and information available to everyone’.57 Contradicting this explanation, the Count boasted in an email to his accountant, Mark Cliff, that he used ‘aggressive incentive payments to key decision-makers’ on transactions.58

The money trail from BAE to Valurex is unsurprisingly complicated, with Red Diamond allegedly paying another British Virgin Islands entity, Prefinor, which in turn held consulting contracts with Foxbury and Valurex, both companies controlled by Landon.59 Investigators identified €6.3m which passed through Prefinor and Brodman. Of this, 30 per cent, €1.9m, was thought to be the commission to be divided between Mensdorff-Pouilly and Landon. This money passed into another secretive financial vehicle, a foundation in Liechtenstein called ‘Kate’. Authorities established that Mensdorff-Pouilly was involved in the foundation, which was named after Timothy Landon’s widow and Mensdorff-Pouilly’s cousin Katalin Landon, known to friends and acquaintances as Kate.60

Gripen Aircraft interim five year deal/lease

Government of contracted authority: Czech Republic

Advisor: Valurex International SA succersale de Genève

Payments: €5.33 million, $1 million, £2 million

The fee schedule will be paid in instalments as detailed:

1,125 M Euros 31/8 2004 PAID

1,125 M Euros 31/12 2004 PAID

1,125 M Euros 31/7 2005 PAID

1 M US $ 31/8 2005

1,2 M £ 31/8 2005

800 000 £ on delivery of the final 8 aircraft

1,125 M Euros 31/12 2006

Count Mensdorff-Pouilly is the primary contact for the provision of the services under the terms of this agreement.54

In 1995, when BAE was constructing its infrastructure of offshore companies for covert payments, the company had identified Liechtenstein as the best European region for its devious purposes. Foundations such as ‘Kate’ registered in the principality are not subject to normal accounting or transparency requirements. They can also be rapidly set up and shut down. Austrian investigators attempted to find out more about ‘Kate’ but lawyers for the foundation appealed against any disclosure.61

Where the payments flowed from Mensdorff-Pouilly is not certain, but according to research by an Austrian magazine, a Russian deputy called ‘Tishchenko’ received €3m. A Vienna-based company called Blue Planet was also named as a recipient, as were the mysteriously named projects ‘Singapore’, ‘Russia’ and ‘India’. €4.7m also flowed to a Viennese businessman, Wolfgang Hamsa, a specialist in offshore companies.62

The use of so complex and discreet a method for diverting funds suggests that these were proceeds from the covert dimension of Mensdorff-Pouilly and Landon’s work for BAE.63

Figure 4: BAE’s Eastern European network64

Key: Dotted grey lines = payments; grey = consultancy agreements; black = ownership; dark boxes are companies

Joachim Dyfvermark (as James Kershaw) and Rob Evans (as Dr Miller) went undercover to unearth more about the deal. Posing as representatives of a fictitious British company, ESID, they claimed to be working for a client, presumed to be BAE. They explained that their client was attempting to assess exactly what had transpired on the Gripen deal in order to plan a strategy in case the story broke in the media. They visited a former senior civil servant who worked for Mensdorff-Pouilly. He told them about the connection between the Austrian and Svoboda, the Finance Minister in the 1990s. ‘I bring Svoboda to Mensdorff, I introduced him.’ The civil servant said that he had heard nothing about bribes but then admitted that he works for BAE on offset deals. He ended the interview abruptly: ‘I don’t know who is your client. I don’t want to know it. My contractor is Mensdorff – I can speak only with Mensdorff.…’65

After communicating with him by phone, the undercover reporters met with a former Czech Foreign Minister, Jan Kavan, in a central Prague hotel. They gained the trust of the minister by citing information that would only be known to an insider on the Gripen deal. They asked what Kavan thought the consequences would be if the police investigated the deal:

Kavan: That could be quite disastrous.

Undercover Reporter: Sorry?

K: That could be quite disastrous.

UR: Oh, you mean so…?

K: If Steve Mead would tell the police everything that he knows, and he was himself involved in. That could involve a large number of important people here. Yes.66

Kavan, denying that he ever took money, acknowledged that other high-ranking politicians were bought by Steve Mead in the Gripen campaign.

K: I was never part of any discussions, or approached about the kick backs. Because they [both] knew I was basically so pro British. They were much more interested in the people in the middle. Who had no views or had to be persuaded or bought. But the fact that money changed hands in the parliament at least was a pretty well known secret shared by a large number of people.

UR: Because we are talking about both ODS and …

K: The Social democrats …

UR: Yes.

K: It went across the political spectrum. And also Christian Democrats.

UR: Yes.

K: We are talking about all three [parties] …67

Kavan was Foreign Minister and later Deputy Prime Minister in the Social Democrat government elected in 1998. His tenure, a full four-year term, was not without scandal, after a large sum of money was found in his office and his senior civil servant was charged with hiring a hitman to liquidate one of the country’s best journalists.68 He was posted to the UN between 2002 and 2003, at one point working as President of the UN General Assembly. The reporters got the experienced statesman talking about Julian Scopes and Steve Mead. Scopes was BAE’s head of Eastern Europe, Steve Mead’s boss.

K: Julian Scopes was also involved but he was more careful, Mead was everywhere.

UR: Yes.

K: Julian was kind of overseeing, but Julian Scopes also had the information. I had secret meetings with both of them but Mead was the one who did the nitty-gritty work on the ground, yes.69

Kavan knew about Valurex and became visibly concerned when told that the police were aware of the company.

K: They received this from the Austrian or from Switzerland?

UR: Don’t know for certain, they are very good.

K: So they would have all that?

UR: Yes!

K: (Big sigh)

UR: How many know of the Valurex?

K: I have no idea, but not few.

UR: Sorry?

K: It will not be just few.

UR: It could be widespread?

K: (Nods)

K: If they investigate thoroughly the Pre-Gripen negotiations led by Steve Mead primarily, it will send shivers down the spine of many … My hunch is that it will involve dozens.70

Kavan offered to ring round a few friends, senior politicians who might know more. In a subsequent telephone conversation he also mentioned that he might try to delay any police investigation:

UR: Would it be possible to have an effect on the police investigation?

K: Aah, I would think that that is not out of the question, but let’s discuss that directly and not necessarily on the phone …

UR: But it could be possible?

K: I think so yes.71

The reporters had so convinced Kavan of their bona fides that even after they left Prague he continued to talk to them. Communicating via the email and phone of the fake company the journalists had set up, Kavan tells them:

K: Since you left I made some inquiries from my close friends. Most of these questions can be fairly easily answered by a friend of ours who runs a consulting firm which had a contract, but not a signed one, an informal contract, with Steven. And cooperated with him for quite a long time.

UR: Based in Prague?

K: Based in Prague and who has a fair amount of the information. We could meet anywhere, London, Paris … whatever. No problem.72

They met up with Kavan and ‘the consultant’, Petros Michopulos, in a hotel just outside London on 17 January 2007. Michopulos told them of his work with Mead:

Petros Michopulos: With us, Steve Mead was always very open. But he didn’t tell week by week whom he bribed and not bribed. But we were in contact with him daily, we saw each other about three times a week. In some cases he told us like it was, in some cases you could tell from people’s changed attitude.

K: His main activities was against the ODS and the social democrats.

UR: In terms of paying kick-backs?

K: Yes, that’s what he is talking about.

Michopulos turned to Kavan and said in Czech: ‘I don’t know how many names to give them.’ Kavan responded: ‘Don’t give them all at once.’ Michopulos agreed, before continuing:

PM: The other group he communicated with economically, I’m sure they were civil servants, not only politicians. Above all people from the Department of Defence and the Defence Command. The Department of Industry, of Trade,… and of Finance.73

He maintained that he took no part in the bribing and reiterated that Mead was key:

PM: Steve was the central figure in this whole deal.

K: Nothing was done without Steve knowing about it.

PM: To judge from what I heard or can guess he did it rather intelligently. It’s like that, the corrupt person always will have someone at his side, be it a physical person, a company or an institution, who does business with someone else, and from that deal will finance this bribe. I don’t think that you can find one instant where the money goes directly to some politician’s, statesman’s or official’s account.74

Michopulos confirmed that BAE spent large sums of money on the underhand Gripen campaign:

PM: BAE gave out much more money on these things than what Steve actually spent.

K: The amount of money allocated by BAE for kick-backs, the volume of expenditure in the Czech republic in connection with this project, was larger than the amount of money actually spent by Steve Mead.75

This was deeply incriminating information. However, when Kavan eventually realized that the two people he was meeting were not working for BAE but were journalists, he changed his story. He told Swedish TV:

When in fact I acquired the suspicion, not the suspicion that they were journalists, but suspicion that this is about corruption and that they are involved in something which I consider illegal, I went to the Czech police and informed them about this and gave the names Mr Kershaw and Mr Miller (their pseudonyms) and the name of this organisation and described in detail my suspicion that they actually want us to circumvent or slow down police investigation of corruption.76

Though Kavan claimed he spoke to Czech police in early January, no police contact was made with the journalists or their front company. Even if he was telling the truth, he still waited a month after the meeting at which he told the reporters that he could slow down a police investigation. He tried to justify attending the meeting in London:

K: I had contacts with the journalists even after we had the suspicion and informed the police because I was hoping that we could acquire from the conversation more information.

Swedish TV: Mr Kavan, the camera does not lie, and you are heard on the tapes saying that money changed hands, that this will send chills down the spine of many important people, that a number of people were bribed, that BAE’s manager in Prague was handling the kickbacks. Now you are saying something else. Are you taking a responsible position here? Are you upright about this?

K: I’m absolutely honest and straightforward. I’m saying that I was sharing with them what I described as rumours and speculation that abounded in the parliamentary corridors about certain kickbacks that might have taken place. I’m not denying that those speculations were heard and that I passed them on to those two gentlemen. I’m saying that I personally can’t prove it, I have no evidence that any such corruption has taken place.77

Petros Michopulos added: ‘Your reporters raised the corruption issue and claimed to have the evidence. I hope I’m not that evidence, because that would be serious manipulation.’78 Kavan wrote to the Guardian after the publication of an article about their undercover sting:

Let me make it clear that I did not ‘admit’ anything. I only shared with two undercover journalists, posing as representatives of a British security organisation, rumours and speculation that abounded some years ago around the Czech parliament. I made it clear to them that I had no real evidence of any bribery.… If I had known they were journalists, I would obviously have been more cautious but also more precise. They would have obtained a result which was less sensational but more reliable.

Jan Kavan

Former foreign minister, Czech Republic79

Saab was not an innocent bystander while BAE was weaving its nefarious webs. The deepthroat who exposed the corruption commented that ‘the Swedes, Per Andersson among others, were also talking about bribes, but they were less specific’.80 Per Andersson was the head of Saab’s campaign for the Gripen Czech Republic deal. Several people at Saab heard Steve Mead talking about how politicians were bribed:

Steve Mead spoke openly about it with quite a few people. Both Swedish and British people heard it, because Steve was pretty dictatorial, and he wanted to enrol all of us. Per Andersson, Saab’s campaign leader, was a part of the inner circle that discussed the whole arrangement – which political contacts were on ‘our’ side, which were on the ‘other’ side and which members were in the ‘middle’ – marked with amber on Steve’s board – they needed to be approached and persuaded.81

When asked for an interview, Andersson responded: ‘No, this is nothing I have any knowledge of whatsoever. I have left Saab, and I don’t work with this at all anymore. I have no comments to make or anything to say about this, other than that it’s nonsense, preposterous.’82

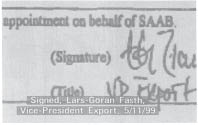

The whistle-blower’s account was not the only evidence of Saab’s involvement. Mensdorff-Pouilly’s contract was signed by a senior Saab executive as follows: ‘I approve the terms of this appointment on behalf of Saab, Signed Lars Göran Fasth, vice-president Export, 5/11/99’.83

Fasth was clearly rattled when approached for comment:

Lars Göran Fasth: I have no idea what you are talking about.

Swedish TV: I sit here with your signature in front of me. Was it you who took decisions like this yourself?

(Long pause)

LGF: No, I must say that I … don’t have … the picture you describe clear to me.84

Saab’s official anti-bribery policy did not cover the agreement with BAE; therefore, corruption by agents employed by the British would not violate Saab’s policy, even if the bribes were for the Swedish company’s benefit and even though notes from BAE meetings showed that Gripen International was directly involved in decisions around payments.85 Gripen International made clear in a series of meetings that they found the original commission rate of 4 per cent for Valurex too high: ‘Gripen International are uncomfortable with indemnifying BAE to this level because the basis of the deal may change, i.e. the Swedish government may supply used aircraft direct and the deal may become government-to-government.’86 Anders Frisén, Saab’s commercial director, was the Gripen International representative at the meetings. The note reveals that Saab and BAE wanted to lower Valurex’s commission and try to make it a fixed sum rather than a percentage. But as the document puts it: ‘The fee will be confirmed at a later date…’87

Josef Bernecker, a former chief of the Austrian Air Staff, confirms working with Mensdorff-Pouilly for Valurex on behalf of BAE and Saab:

Swedish TV: You two work together for Valurex?

Josef Bernecker: Yes, as consultants. I do it on the military level, since – I know all my people from the past and Mensdorff on the political level …

STV: So he is kind of doing the lobby work on the politicians?

JB: Right. Right. I started with Mensdorff when I retired.

STV: Yes.

JB: And at that time the deal was done already, so I was more or less in the aftermath of the whole thing. He was doing some political or social lobbying …

STV: For?

JB: Yes, for the deal …

STV: For the lease deal …

JB: But on behalf of Valurex.

STV: But Mensdorff is Austrian, how come … I mean Czech Republic is Czech Republic?

JB: You know, these noblemen, they are well connected, well netted all over Europe, so it’s just that he knows a lot of people.

STV: Was that on behalf of BAE and Saab?

JB: Yes, I think so, yes, or at least they knew about it.

STV: Saab?

JB: Yes, yes!

STV: Alright, because …

JB:… or Gripen International.88

The involvement of the Count’s third cousin, the lyrically named Michael Piatti-Fünfkirchen, illustrates how well-connected ‘these noblemen’ are and how they strive to keep business in the family, which often ends in tears.

In the 1990s, Piatti-Fünfkirchen was close to a range of luminaries within the Czech government. Mensdorff-Pouilly offered his cousin a commission of €1m if he used these contacts to ensure the Czech government bought the Gripen.89 A number of high-level meetings in the summer of 1998 involving Czech officials, a BAE manager and finally the Czech Finance Minister, Ivo Svoboda, came to nothing. The Count determined that because the proposed sale was scrapped in favour of the lease deal, Piatti-Fünfkirchen was not entitled to a commission.90 The irate cousin later filed a fraud complaint against Mensdorff-Pouilly, accusing him of ‘suspicion of serious fraud’ in his efforts to convince the Czech government to buy the Gripen.91

This is what landed the Count in a Viennese prison for five weeks from late February 2009, where he was kept in preventive detention on bribery charges. The judge detained Mensdorff-Pouilly because of the danger of ‘obfuscation and additional crimes’ by the lobbyist.92 Mensdorff-Pouilly complimented the wardens and food in the Viennese prison and recalls: ‘Sometimes I stood in front of the mirror saying to myself: “Ali, you’re in jail – accept it!”’93 During my conversation with him, he described how the arresting officers, prosecutors and prison officials always treated him with respect, addressing him as ‘Count’ despite Austria’s banning of the use of aristocratic titles from 1919.94

* * *

The SFO had begun investigating BAE in July 2004 for allegations of corruption in the Czech Republic, along with South Africa, Tanzania, Chile, Qatar and, in 2006, Romania.95 Czech police reopened their inquiries following the screening of the zetetic Swedish TV documentary in 2007. At the request of the SFO, Austrian police raided Mensdorff-Pouilly’s home in late September 2008, seizing a large quantity of documents.96 In October, the SFO interviewed the Count. Julian Scopes was interviewed by UK police. In February 2009, Mensdorff-Pouilly was arrested by the Austrian authorities and questioned about an £11m payment allegedly made to him by BAE.97 He was charged by the SFO on 29 January 2010 with conspiracy to corrupt in connection with BAE’s deals with Eastern and Central European governments, including the Czech Republic, Hungary and Austria.98 However, after a bail hearing in which the patrician Conservative MP John Gummer (now Baron Deben) gave Mensdorff-Pouilly a glowing character reference, the Count was granted bail of £500,000 deposited with the court and £500,000 in surety, during which he was allowed to stay in a Belgravia flat wearing an electronic tag, under curfew between midnight and 6 a.m., and was made to surrender his three passports.99

Austrian prosecutors continue to scrutinize the Count’s activities.100 The FBI initiated an examination of the Czech Gripen deal as a consequence of the bureau’s interest in Erste Bank, one of the largest financial services providers in Central and Eastern Europe, through which cash may have flowed as part of bribes in the transaction.101 The Czech authorities have played the investigative equivalent of musical chairs, opening and closing inquiries into the deal with startling regularity. At the time of writing their investigation remains open.102

A Swedish inquiry into the Gripen deals in the Czech Republic, Hungary and South Africa started in March 2007103 but was dropped two years later when the Swedish chief prosecutor, Christer van der Kwast, concluded that:

The inquiries showed that BAE, using a sophisticated payment arrangement, has hidden large payments that can be linked to the campaigns in the Czech Republic, Hungary, and South Africa and have made it possible to bribe the decision makers in these countries. It is very serious, both in terms of the systematics and the amount. It involves hundreds of millions of Swedish crowns in hidden payments in several countries, and there is strong reason to believe that bribery also has occurred. But I cannot fully verify that Saab participated in the bribery payments. But I have made the judgement that in court I could not prove that some representative for Saab has intentionally participated in the payment of the bribes.104

He questioned over thirty people within Saab without receiving a reasonable explanation as to why vast amounts of Swedish crowns were passed to middlemen. ‘No, I have not got that [explanation],’ van der Kwast said. When asked how believable he found Saab’s contention that it was normal business activity, he replied: ‘I do not want to answer that except to say in my opinion the collected evidence is not enough to prosecute any representative of Saab.’105

Due to the statute of limitation in Swedish law, van der Kwast was not able to prosecute for what had taken place prior to 1 July 2004. He also believes that Sweden does ‘not have laws that effectively cover this type of arrangement between middlemen and consultants’.106

The Swedish inquiry was criticized by the OECD due to the very limited resources devoted to it – one investigative policeman. Van der Kwast was also subject to inappropriate, albeit indirect, pressure. ‘They have emphasized that these inquiries are of course damaging to Swedish business,’ he said. When asked who says that, the prosecutor responded: ‘I don’t want to go into that. I don’t want to say more than that. But from my position, from the policeman’s position, it is understood as a sort of indirect hint to take it carefully.’107 Christer van der Kwast’s findings were reported the day before he retired as chief of the National Agency Against Corruption.108

Vaclav Havel was shocked by the revelations that emerged years later and by the corruption ‘in the army sphere’.109 His dream of a politics of morality appears more distant than ever.

Hungary: ‘The Happiest Barrack’*

Lieutenant General Tome Walters Jr, former head of overseas sales for the Pentagon, claimed that the problems in the process to sell fighter aircraft to the Czech Republic were mirrored in efforts to sell American jets to the government of Hungary. Ultimately BAE secured the Hungarian contract as well, with American officials claiming that both the Hungarian and Czech governments were influenced by improper payments. They cite a CIA briefing during which they were told that BAE paid millions of dollars to the major political parties in Hungary to win the contracts there.110

In 1999, the Hungarian Cabinet issued a tender for the purchase of used fighter aircraft. In June 2001, the government announced that the American arms behemoth Lockheed Martin had won the contract. Hungarian military experts considered the American F-16 superior to the Gripen and recommended it for lease and eventual purchase in a document dated 6 September 2001. The decision was endorsed by János Szabó, the Minister of Defence.111 A few days later, at a small gathering of the National Security Cabinet chaired by the Prime Minister, Viktor Orbán, the Swedish Gripen was chosen in an unexpected volte-face. All government documents pertaining to the decision-making process around the startling deal were destroyed.112 In 2003, Hungary finalized a contract to lease fourteen Gripen fighters for Ft.210bn (approximately €823m) for ten years, after which the planes would become Hungarian-owned.113 The first of the aircraft was delivered in January 2005 at a ceremony attended by the two countries’ defence ministers.

Hungary cited as one of the main reasons for its selection of the Gripen Sweden’s offer of 100 per cent offset for the $500m lease deal, which included 30 per cent in investments in Hungarian industry.114 This justification was given in spite of the evidence that these offsets obligations are rarely fulfilled.

In both the Hungarian and Czech deals, the Lockheed Martin F-16 was thought to be the favourite, fuelling suspicion of underhand activity. In an SFO report submitted to the Austrian investigation into Alfons Mensdorff-Pouilly, an extract concerning the Hungarian deal suggests that ‘the references to making political payments are much more unequivocal. This becomes clear from a minute over a conversation with BAE personnel, Julian Scopes and David White … [It refers] to “payment to the socialists 7.5%”.’115 At the time, Scopes and White were BAE executives for Central Europe, the former having served as Private Secretary to the former Conservative Defence Minister, Alan Clark.

In agency documents labelled ‘Strictly confidential, Gripen Europe’, Mensdorff-Pouilly is listed as the agent for Hungary, with a success commission of 3 per cent. In addition, the Austrian received a fixed annual remuneration from BAE, plus expenses for his company, MPA. But the enormous commission was to be paid via Prefinor International in the British Virgin Islands.116

Even though the deal was ultimately not a sale but a state-to-state leasing contract, Mensdorff-Pouilly was still paid. In a secret agreement of March 2002, three months after the state-to-state deal was signed, payments amounting to $8m were identified ‘for 8 years of services to the Gripen project’.117 The money was to be routed through Red Diamond to Prefinor and from there to Mensdorff-Pouilly in Austria.118 When questioned about these arrangements, the Count’s spokesman responded: ‘Alfons Mensdorff-Pouilly or any one of his companies have never received any commission from BAE or Saab.… neither Alfons Mensdorff-Pouilly, nor one of his companies were contracted by BAE or Saab as agent to promote the sale of Gripen.’119

In June 2007, following the airing of the allegations on Swedish Television, the Hungarian Defence Minister announced that the authorities would look into the ‘alleged improprieties’.120 But the Hungarian committee examining the contracts was not authorized to investigate corruption and, therefore, ‘declined to pursue the possibility of it’, the director of the committee said. Ágnes Vadai, who is also a State Secretary for the Ministry of Defence, added that a new parliamentary committee would have to be formed to investigate corruption.121

* * *

When I met Count Mensdorff-Pouilly in Vienna, besides repeating that he only ever received a retainer from BAE, he claimed credit for the leasing arrangements, saying that in conversations with government officials in the Czech Republic and Hungary he understood that their economic and political circumstances would not allow them to purchase the jets. He claims to have suggested the leasing arrangement, explaining that he then had to persuade BAE, and finally Saab, of the proposed approach. The latter were particularly wary of the proposal because of fears of not being paid. The Count used this as an example of the type of service he provides, stressing, somewhat disingenuously, that he would never explicitly suggest to government representatives with whom he had such regular contact that they buy a specific plane from any company, let alone the one from which he was receiving a retainer.122

Contradicting his denial that he had pitched for BAE/Saab business, he remarked that if only the partnership had used him in Poland they would have won that contract as well. He claims that the Americans paid bribes to win the Polish deal, which was why they were so keen for bribery to be revealed in the deals they lost out on. ‘A type of insurance,’ he suggested, ‘so that the British and Swedes wouldn’t be minded to expose American corruption.’123

* * *

After a few hours of discussion, primarily denial, I asked the Count why it was necessary to direct his retainer payments through a fiendishly complicated web of companies in the BVI, Liechtenstein, Switzerland and elsewhere. He shrugged his shoulders: ‘I don’t know. I just receive my money in Austria, sometimes via Switzerland for personal reasons.’124

Finally, the charming Count admitted that he’d done some bad things in his life: ‘maybe too much wine, too many women … but I have never paid bribes. I talk to all sorts of influential people, I can talk to anyone in my party [the ÖVP], but would never tell them to buy Gripen rather than … I would never pay a politician to make a decision.’

But in response to my question about why commissions are paid, such as those he suggested were disbursed by the Americans in Poland, he explained how when he was in the game and poultry business: ‘one had to give presents, benefits, incentives. This [rubbing his thumb and index finger together] applies to all business.’125

‘This’ has certainly done well by the very comfortably off Count Mensdorff-Pouilly.

A Very Swedish Paradox

Arguably the most famous Swede of all time, Alfred Nobel, claimed that ‘I should like to invent a substance or a machine with such terrible power of mass destruction that war would thereby be made impossible for ever.’ His life, and his view of the world, reflected this continuous dichotomy. He was a poetic idealist and a pacifist, but also a ruthless financier, obsessed with the science of explosives. Isolated and tormented, Nobel invented dynamite, then later in life bought the Swedish gun manufacturer Bofors and created the annual peace prize.

That duality lives on after him, both in the disputes over the awards of his peace prize and in the ambivalence of Sweden itself, which is still both an inventive manufacturer and exporter of arms and a persistent campaigner for world peace.126 The country boasts an arms industry that has consistently been among the ten largest weapons exporters in the world, led by Saab, which produces, on average, 70 per cent of all weapons manufactured in Sweden. At one point BAE owned 20 per cent of Saab, as well as Hägglunds and Bofors. As Swedish military spending has dropped over recent years to 1.2 per cent of GDP so Saab’s exports have grown to account for over 65 per cent of all sales.127

While governments of all political persuasions once argued that a thriving home-grown weapons manufacturing capability was vital for Sweden to maintain its ‘credible neutrality’, now the main reason for its weapons industry is to make money. And export sales are crucial to this. This accounts for the very weak enforcement of the country’s strict regulations. As Henrik Berlau of the Seaman’s Union in Copenhagen, which monitors international arms trafficking, has said: ‘Sweden has a very strict law, but a very relaxed attitude toward enforcing it.’128

Just as the Nobel Peace Prize will always carry a sense of ideals thwarted, so too does the Swedish arms industry, which has been mired in controversy, corruption and double-dealing for decades.

Saab opened an office in New Delhi in order to sell Gripen jet fighters worth $10.2bn to India, but failed to make the competition shortlist.129 This came after the successful conclusion of a controversial SEK8.3bn deal to sell six Erieye airborne radar systems to Pakistan in 2006, intended as a precursor to the sale of Gripens.130

Controversial arms sales from Sweden to South Asia are nothing new. When Olof Palme, Sweden’s Prime Minister, made his second visit to India in 1986, he and his Indian counterpart, Rajiv Gandhi, were at many levels political soul-mates. Palme was widely revered as a global socialist icon and a champion of world peace. Gandhi, standard-bearer of Nehru’s Congress movement, had been elected as ‘Mr Clean’ on a promise to eradicate the insidious corruption that had plagued democratic India since its birth.

However, during the course of their discussions the two leaders agreed an arms deal that would blight their countries for decades to come. India’s military was desperate for powerful, high-tech howitzers to counter the state-of-the-art artillery that the US was selling Pakistan. Palme wanted the contract for Bofors, the historic Swedish gun-maker, part of Nobel Industries, which badly needed the business if it was to avoid layoffs that would be politically costly for Palme’s government.131

Bofors got the business: a huge $1.4bn order, even though India’s military preferred a French artillery piece which was cheaper, had a longer range and was regarded as more reliable – the French equipment prevailed in eight consecutive evaluations. $250m in bribes was paid to secure the deal.

Having publicly stated that India would not utilize any agents and that no commissions would be paid, Gandhi privately informed Palme that the deal would be awarded to Sweden on condition that Bofors changed their Indian agent. Bofors made use of Gandhi’s preferred agent, AE Services, but retained their original agents, renaming them consultants to the project. One of these, Svenska Inc., received $29.44m, while AE Services received a remarkable success fee of $168m.

Despite extensive efforts in Sweden and India to cover up this corruption, investigative journalists in both countries published revelatory accounts that led to them receiving death threats, court orders and even, in the case of the Indians, being forced into exile. Crucially they established that AE Services was owned by one Ottavio Quattrocchi, an Italian and a close family friend of Gandhi’s wife, Sonia. Neither Quattrocchi nor his company had any prior experience in the arms business. This devastating exposé contributed to Rajiv Gandhi’s defeat in an election in late 1989 that was fought on the issue of corruption. Quattrocchi spent years attempting to block Indian access to his Swiss bank accounts. Despite many of those involved dying, and some being reprieved by the courts when Congress returned to power, the main issues remain.

In December 2005, the Indian Congress government unfroze Quattrocchi’s British and Swiss bank accounts. However, a few days later the Indian Supreme Court demanded that the Indian government ensure Quattrocchi be prevented from withdrawing further money from the accounts. In 2007, the court issued a warrant for his arrest. In late September 2009, the recently re-elected Congress government told the Supreme Court it was dropping the case against Quattrocchi.

In early 2011, the Bofors phoenix rose again from the ashes. An Indian tax tribunal ruled that the son and heir of one of the Bofors agents, W. N. Chanda, was liable for tax on the commissions received. The tribunal concluded in a damning verdict for the Congress Party that ‘there is enough material on record to hold that the payments were indeed made by Bofors to Svenska, AE Services and Moresco through foreign bank accounts, in connection with the defence deal with the Government of India’.132 Ottavio Quattrocchi was named by the tribunal as one of the beneficiaries of kickbacks.133

The Hindu newspaper argued that ‘Unlike other corruption scandals, Bofors has refused to go away as a national issue – because the deep-seated political, moral, and systemic issues it raised won’t go away.… [The case illustrates] how various institutions perform in relation to corruption. With the executive branch resorting to flagrant cover-up and obstruction of justice, Parliament, the Central Bureau of Investigation, and the judiciary failed to do the right thing by the people of India.’134 The main opposition party called for a Special Investigating Team to reopen and again investigate the Bofors ‘kickback scam’.135

While the scandal continuously re-emerges in Indian politics more than twenty years after the deal was signed, the guns have not been used extensively. Though they performed ably in the Kargil conflict, wear and tear and a lack of spare parts led to many of them being cannibalized, leaving only 200 operational.136 One account suggests that a number of them were mothballed as they overheated when fired.137

Some in Sweden speculate that his involvement in this and other arms deals might have been behind the still unsolved assassination of Olof Palme. These theories are lent credence by the Social Democrats’ complicity in allowing the sale of arms to Iraq and Iran during the conflict between those two countries. In the early 1980s, during a period in opposition, Palme had been acting as the UN’s peace mediator between Iran and Iraq. After his return to power in 1984 he was deeply embarrassed by revelations that arms shipments were being made to the region from Sweden through Singapore, Dubai or Bahrain. Directors of Bofors insisted that this was done with the full knowledge of the government. Palme then stopped the shipments and received enraged delegations from Iran and Iraq just three weeks before his murder.

A year after Palme’s murder a former admiral, Carl-Fredrik Algernon, who was the foreign-ministry officer responsible for approving all arms exports, either fell or was pushed in front of an underground train in Stockholm’s Central Station just after he had come from ‘a very revealing meeting’ and six days before he was to appear before a special prosecutor investigating the illegal arms shipments.

Today the reputation of the Swedish arms industry, and Saab in particular, is inextricably linked to BAE. In South Africa, the Czech Republic, Hungary and Austria tales of inappropriate influence and corruption haunt the image of this bastion of peace.

I asked Thomas Tjäder of the Swedish Inspectorate of Strategic Products (ISP), the body that oversees the country’s arms exports, whether these accounts influence his organization’s decisions to grant future export licences to companies. After discounting the importance of negative socio-economic impact on the purchasing country, he added: ‘All bribes are illegal but, if a Swedish company paid bribes in another country, I can’t say we would do anything about it.’138

Perhaps this attitude isn’t surprising given that Tjäder is not only a former Department of Defence official of nineteen years, a senior councillor for the Conservatives in Uppsala and the chairman of six companies, but, before joining ISP, was a director of Celsius, a defence company.139

When he was appointed to the ISP a number of people were shocked, suggesting ‘he would rather work to increase arms exports, than to control them’,140 reflecting the contradiction at the heart of Sweden.