16. Beyond Utopia, Hope?

The transition from the defence contractor utopia of George W. Bush to the potentially more difficult Obama administration has been fairly seamless for the weapons business in the US.

While during his campaign and the early months of his presidency, Barack Obama talked tough on the need for fundamental change to the way the defence industry and the Pentagon operate, the reality is that there has been only very small, peripheral change. On the whole it is business as usual for the MICC.

Pentagon budgets suggest that the amount of money available to defence contractors has undergone little change. In fact, in 2011 basic funding levels – not including money set aside for the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq – were in line with the last Bush administration budget, right down to prospective further increases. The overall figure for the 2011 Pentagon budget was actually $513bn; that is higher than Bush’s last base budget. The preliminary figure for war-fighting in 2011 was $159bn, which represents a slight increase from the $155bn that went to military operations in 2010. Add that to the base Pentagon budget and you get a subtotal of $662bn for 2011 military expenditures. If the estimated costs of military spending lodged in other parts of the federal budget (like funding for nuclear weapons, which falls under the Department of Energy), as well as miscellaneous non-Defense Department defence costs – about $17bn last time around – are also included, then President Obama’s most recent military budget comes in at around $689bn.1

Unsurprisingly, after the preliminary budget figures were released the Secretary of Defense, Robert Gates, who was kept in post after Obama assumed office, told reporters: ‘In our country’s current economic circumstances, I believe that represents a strong commitment to our security.’2 The administration’s request for 2012 is $703bn.3

Any attempt to cut the overall defence budget will be fought tooth and nail in Congress and within the military, backed by all the lobbying power of the weapons-makers and service providers. The extent of the abiding power and influence of the MICC was evident in relation to the F-22 Raptor, Lockheed Martin’s major weapons system and the most expensive jet fighter in history to date, costing $350m per plane with over 1,000 parts suppliers across forty-four states.4 On 20 January 2009, 200 members of the House and forty Senators signed a ‘Dear Mr. President, Save the F-22’ letter, meant to be waiting for Barack Obama as he entered the Oval Office. The letter asserted that the F-22 programme ‘annually provides over $12 billion of economic activity to the national economy’. Twelve Governors signed a similar letter. Even if that dubious claim were substantiated, the economic activity comes at a high cost: almost $70bn for a fighter that lacks a role in any imaginable war-fighting scenario the US might actually find itself in.5

The letters were accompanied by an advertising blitz from Lockheed Martin, proclaiming ‘300 MILLION PROTECTED, 95,000 EMPLOYED’.6 When asked where the jobs were located, the company claimed the information was proprietary and refused to provide it. As Hartung remarked: ‘Never mind that Lockheed Martin gets almost all its revenues and profits from the federal government – when it’s time to come clean about how it is using our tax money, it’s none of our business.’7

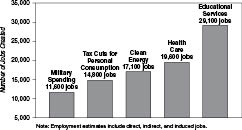

The company had to back away from the 95,000 jobs claim, clarifying that more than 70 per cent of those jobs are only indirectly related to the F-22 and that just 25,000 workers are employed directly on the plane’s construction.8 The irony is that almost any other form of spending – even a tax cut – creates more jobs than military spending. In fact, if the F-22 is funded and spending on other public investments goes down accordingly, there will be a net loss of jobs nationwide.9

Efforts to promote the plane as a critical tool in the War on Terror floundered when Gates said in 2008: ‘The reality is we are fighting two wars, in Iraq and Afghanistan, and the F-22 has not performed a single mission in either theater.’10 In fact, it has never been used in combat.11 Williamson Murray of the Army War College believes that ‘The F-22 is the best fighter in the world, no doubt about it. But there ain’t any opposition out there. It’s sort of like holding a boxing tournament for a high school and bringing Mike Tyson in.’12

This was not the first attempt to stall the F-22. In 1999, John Murtha and the Republican Jerry Lewis surprisingly teamed up to withhold production funding in protest at the programme’s huge cost overruns. They had no intention of killing the F-22, but wanted to get the company’s and the Air Force’s attention. Lockheed Martin pulled out all the stops, deploying a range of ex-Congressmen as lobbyists. From a luxury box at a Baltimore Orioles baseball game to the steam room of the House gymnasium, which ex-members are allowed to frequent, the message went out that allowing funding to slip by even a few months would strike a devastating blow to the country’s security and economy. Former Senator Dale Bumpers described the company’s campaign as ‘one of the most massive lobbying efforts I’ve ever witnessed’. The Air Force, technically prohibited from lobbying Congress, formed a ‘Raptor Recovery’ team ‘to tell our leadership in Congress that we believe the Air Force and the country need this’.13 The Air Force described its intervention as ‘informational’ activity, suggesting it is pretty much able to lobby as it pleases.

The Air Force’s intention at this point was to buy 339 planes for a projected cost of over $62bn – up from an initial proposal to buy 750 planes for $25bn. That’s less than half as many planes for more than double the price. This absurd situation arose because initially Lockheed Martin put in a low bid, knowing that the planes would cost far more than their initial estimate. This practice of ‘buying in’ allows a company to get the contract first and then jack up the price later. Then the Air Force engaged in ‘gold plating’ – setting new and ever more difficult performance requirements once the plane is already in development. And finally Lockheed Martin messed up aspects of the plane’s production, while still demanding costs for overheads and spare parts from the Pentagon. As Hartung observes, this is a time-tested approach that virtually guarantees massive cost overruns.14

From inside the Pentagon, Chuck Spinney described the process as follows:

When you start a programme the prime management objective is to make it hard to cancel. The way to think about this is in terms of managing risk: you have performance risk and the bearers of the performance risk are the soldiers who are going to fight with the weapon. You have an economic risk, the bearers of which are the people paying for it, the tax payers. And then you have programmatic risk, that’s the risk that a programme would be cancelled for whatever reasons. Whether you are a private corporation or a public operation you always have those three risks. Now if you look at who bears the programmatic risks it’s the people who are associated with and benefit from the promotion and continuance of that programme. That would include the military and civilians whose careers are attached to its success, and the congressman whose district it may be made in, and of course the companies that make it. If you look at traditional engineering, you start by designing and testing prototypes. To reduce performance risk you test it and redesign it and test it, redesign it. In this way you evolve the most workable design, which in some circumstances may be very different from your original conception. This process also reduces the economic risk because you work bugs out of it beforehand and figure out how to make it efficiently. But the process increases the programmatic risk, or the likelihood of it being cancelled because it doesn’t work properly or is too expensive.

But the name of the game in the Pentagon is to keep the money flowing to the programme’s constituents. So we bypass the classical prototyping phase and rush a new programme into engineering development before its implications are understood. The subcontractors and jobs are spread all over the country as early as possible to build the programme’s political safety net. But this madness increases performance and economic risk because you’re locking into a design before you understand the future consequences of your decision. It’s insane. If you are spending your own money you would never do it this way but we are spending other people’s money and because we won’t be the ones to use the weapon – so we are risking other people’s blood. So protecting the programme and the money flow takes priority over reducing risk. That’s why we don’t do prototyping and why we lie about costs and why soldiers in the field end up with weapons that do not perform as promised.

In the US government money is power. The way you preserve that power is to eliminate decision points that might threaten the flow of money. So with the F-22 we should have built a combat capable prototype. But the Cold War was ending, and the Air Force wanted that cow out of the barn door before the door closed.15

The Army sided with Lewis and Murtha against the Air Force, in an example of inter-service rivalry, which is one of the complexities of the MICC, where different parts of the military are divided not about how much to spend but about what to spend it on. But in October 1999 Lockheed Martin won $2.5bn more for the F-22 programme.16

Cost concerns lingered into the early months of the George W. Bush administration, but after 9/11 the massive increase in military spending and the new attitude to security saved the F-22 and other threatened projects. As a senior Boeing executive said: ‘the purse is now open and any member of Congress who doesn’t vote for the funds we need to defend this country will be looking for a new job after next November [elections]’.17

It was assumed Lockheed Martin’s lobbying power would ensure the survival of the F-22 even when the Obama administration took office. But, in April 2009, the Defense Secretary, Robert Gates, announced that production of the F-22 would be halted when the last of 187 planes are delivered in 2011. He announced a $13bn increase in spending on military personnel and an extra $2bn for unmanned drone aircraft. He also announced increases in weapons spending, including an additional $4bn for the F-35, another Lockheed Martin product.

Despite this extra money Congress responded angrily. First, the Senate Appropriations Committee demanded that the Air Force study the viability of creating an export version of the fighter jet to sell to Japan and Australia.18 And the House Armed Services Committee provided $369m over two years to purchase parts to construct twelve more of the jets.19

But two weeks after the announcement Lockheed Martin itself seemed to accept that the decision was made. Bill Hartung reveals that in the weeks leading up to his announcement, Gates had met with the company’s CEO, Robert Stevens, and essentially said: ‘If you oppose me on this, I’ll eat your lunch.’ Lockheed’s top management decided to back off on lobbying for the F-22 for fear of alienating their biggest customer.20 Gates also played the jobs card effectively without ever questioning the faulty innate logic of the argument. The acceleration of the F-35 programme would more than offset any F-22 job losses. He claimed that while F-22 jobs would fall by 11,000 between 2009 and 2011, the F-35 programme would gain 44,000 over the same period.21

This didn’t make the Congressional battle any less nasty. The opposition to cutting the F-22 was bipartisan, pork-driven and led by Senators whose home states had the biggest stake in the programme. The Armed Services Committee voted to build seven additional planes in order to keep the production line operating, opening the door to the provision of more funds the following year. The 13–11 vote reflected the domestic politics of the programme. A pork-driven vote in the House Armed Services Committee led to a further $369m to help keep the programme going. And so it went to the Senate floor for a dramatic and conclusive vote.

President Obama announced that he would veto any defence budget that included additional funding for the F-22, a virtually unprecedented and bold move, which he then backed up with some heavyweight lobbying by his administration. Gates himself delivered a speech in Chicago less than a week before the vote in which he lambasted Congress, reminding his audience in the Windy City and Washington that the defence budget was an increase over the last one of the Bush administration and that the US spent more on defence than the rest of the world combined: ‘Only in the parallel universe that is Washington DC could this be considered “gutting” defence,’ concluded the combative Defense Secretary.

In the debate itself, the F-22 was stoutly defended by, among others, Senator Daniel Inouye, a Hawaii Democrat who has spent over two decades on the Appropriations Subcommittee on Defense and describes himself as ‘the #1 guy for earmarks’. In 2009 alone Inouye had brought home over $206m, in return for which he received over $117,000 in campaign contributions from companies that benefited from his earmarks, with half coming from Lockheed Martin.22 As Hartung remarks: ‘Inouye never met a weapon system he didn’t like.’ Obama’s former election opponent, John McCain, dispatching his campaign flip-flopping to return to his reforming roots, argued persuasively that ‘it boils down to whether we are going to continue the business as usual of once a weapons system gets into full production it never dies or whether we are going to take the necessary steps to reform the acquisition process in this country’.23 The vote was carried by a surprisingly large majority of 58 to 40.

Lockheed Martin’s lobbying power had kept the F-22 alive against the odds for so long in a battle that they ultimately lost, but in a war they continue to win. In fact the company will come out ahead of the game under Gates’s budget package, with the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter likely to be the largest programme in the history of military aviation. Sold to Congress with a promised price tag of $62m per aircraft, that has already risen to $111m, an 81 per cent increase per plane.24 An extra $4.4bn was added to the F-35 project in Obama’s first defence budget.25 Although cheaper per plane than the F-22, it is intended that over 3,000 will be bought by the US and UK alone, with another 600–700 bought by partner countries. A Lockheed Martin executive, Mickey Blackwell, described it as ‘the Super Bowl, the huge plum, the airplane program of the century’.26 Northrop Grumman and BAE will have significant roles in the production process, moves that garnered wider US pork and British support for the project.

The usual litany of problems have beset the F-35: 2,000 pounds overweight with inadequate pre-testing and so far behind schedule that it could cost an extra $16.6bn over five years, bringing the total project cost to over $380bn.27 In addition, over the lifetime of the jet, maintenance and running expenses will cost the American taxpayer $1 trillion.28 Chuck Spinney was moved to suggest that ‘the F-35 will be a far more costly and more troubled turkey than the F-22’. In an even more damning indictment of the company and its products, a former Pentagon aerospace design engineer, Pierre Sprey, described Lockheed Martin as ‘always the sleaziest [of the defence contractors] and they make crappy airplanes. The F-35 is a total piece of crap, far worse than the planes it’s replacing.’29

* * *

The Bush presidency and the first year of the Obama administration were good times for US arms-exporting activity as well. Major foreign arms deals by US companies more than doubled from 2001 to 2008, reaching a total of over $31bn. The US lead in the overall global weapons market increased dramatically as well. In 2008, more than two thirds of all new arms sales agreements worldwide went to US companies.30

Significant amounts of money continue to be made available to countries buying weapons from the US. So, in addition to the record levels of defence spending and foreign military cooperation funding (that is often used to buy US weapons and totalled around $5bn in 2003),31 the State Department and Pentagon spend an average of over $15bn per year in security assistance funding, a large share of which goes to finance purchases of US weapons and training.32 In addition, low-rate, US government-backed loans are made available to potential arms-purchasing nations. Such a loans programme existed in the 1970s and 1980s but was closed down after loans worth $10bn were either forgiven or never repaid, i.e. the programme became a further giveaway for US contractors and their foreign clients.33 Despite this history, in 1995 another $15bn loan guarantee fund was signed into law by President Clinton. This followed six years of lobbying by the arms industry, led by Lockheed Martin’s CEO, Norm Augustine.34

Direct pressure from the Pentagon and the White House is often used to close a sale. For instance, in 2002 the US government demanded that South Korea award a $4.5bn contract to Boeing rather than a French company. Leaks from the South Korean defence ministry indicate that the French plane outperformed its American rival in every area and was $350m cheaper. But the Deputy Defense Secretary, Paul Wolfowitz, told the Koreans that they risked not only losing US political support but the American military would refuse to provide them with cryptographic systems that allow aircraft to identify one another or to supply the American-made air-to-air missiles that the plane uses. Boeing was awarded the contract.35

When Colombia considered buying light attack aircraft from Brazil rather than a US manufacturer, the senior American commander in the region wrote to Bogotá that the purchase would have a negative impact on Congressional support for future military aid to Colombia. The deal with Brazil fell through.36

Of all the monies spent today in the US on foreign affairs, 93 per cent passes through the Department of Defense and only 7 per cent through the State Department. This both reflects the support given to the weapons manufacturers and is indicative of why the US so often turns to the military option in solving international problems.37

And, of course, Lockheed Martin is the biggest beneficiary of this trend, and one of its biggest export items is the F-16 fighter plane. Since 2006, the company has entered into agreements to sell F-16s worth nearly $13bn to Romania, Morocco, Pakistan and Turkey. A relatively new, even more lucrative development is the large-scale export of current-generation Lockheed Martin missile defence systems. During 2007 and 2008, the company made agreements to sell one or more of these systems to the United Arab Emirates, Turkey, Germany and Japan for a total of over $24bn. Its C-130J military transport planes are destined for Israel, Iraq, India and Norway in deals worth nearly $5bn. Additional sales of Hellfire missiles, Apache helicopters, and various bombs and guidance systems are earning the company billions more.38

One of the most controversial recent sales of Lockheed Martin equipment was a $6bn deal with Taiwan that included 114 of the company’s PAC-3 missiles at a cost of $2.8bn.39 The deal sparked an angry response from China, which threatened to cut off military-to-military cooperation with the United States and impose sanctions on US firms whose equipment was part of the deal. As of this writing, the threatened sanctions had not been imposed and military relations were pretty much reinstated.

Lockheed Martin argues that its weapons exports provide stability by deterring war, but critics suggest that weapons exports fuel arms races and make war more likely: does Romania need to spend $4.5bn on F-16s? Isn’t Pakistan more likely to use its F-16s against India than against Al Qaeda or the Taliban? Does buying missile defence technology to a value of over $15bn protect the United Arab Emirates or is it just making this purchase to curry favour with Washington?

In Turkey, for example, Lockheed Martin-supplied F-16s didn’t just sit on a runway: they were used in a brutal fifteen-year war against Kurdish separatists affiliated with the Kurdish Workers Party (PKK) that left thousands of villages bombed, burned and abandoned, and tens of thousands of people dead. Of the people driven from their homes during the conflict 375,000 have yet to return.40 Although the F-16 was far from the only weapon used in suppressing the Kurds, it was featured in air strikes – both within Turkey and in raids against alleged PKK sanctuaries in Iran and northern Iraq – that helped set the stage for more intensive raids using attack helicopters, armoured personnel carriers, rifles and anti-tank weapons. Joel Johnson, then a lobbyist for the Aerospace Industries Association, of which Lockheed Martin is an active member, tried to justify Turkish bombing of Kurdish areas by essentially saying that everybody does it:

It must be acknowledged that the Turks have not invented Rolling Thunder. We used B-52s to solve our guerrilla problem [in Vietnam]. The Russians used very large weapons platforms [in Afghanistan]. And Israelis get irritated on a reasonably consistent basis and use F-16s in Southern Lebanon. One wishes it didn’t happen. Sitting in the comfort of one’s office, one might tell all four countries that they’re wrong. It’s a lot easier to say that here than when you’re there and it’s your military guys getting chewed up.41

Israel has been another major user of Lockheed Martin products and is a good example of how difficult it is to control the use of exported weaponry once it is delivered, even when the recipient is a close ally (see Chapter 17).

The company’s involvement in virtually every facet of missile defence was underscored by President Obama’s September 2009 decision to scrap a Bush administration plan to place missile defence components in Poland and the Czech Republic. Although Boeing, which is responsible for the radar system that would have been deployed in the Czech Republic under the Bush plan, stood to lose from President Obama’s change in course, it appeared that Lockheed Martin might actually come out ahead. This unexpected outcome is tied to the fact that the Obama administration did not abandon missile defences in Europe – it just restructured them. Leaked Pentagon documents indicate that the number of Lockheed Martin interceptor rockets deployed in Europe could quadruple under the Obama plan.42

And in January 2010, just three months after Obama announced the restructuring, plans for the deployment in Poland of Lockheed Martin-made PAC-3 missiles were announced. Then, in early February, Romania’s President Traian Basescu announced that his country was entering talks with the Obama administration to place PAC-3 missile interceptors there. The fact that Lockheed Martin should benefit from a change in missile defence policy is not so surprising given the company’s extensive role in the roughly $10bn per year missile defence programme. As with the termination of the F-22 programme, the company is big enough and diversified enough to weather the cuts. For Lockheed Martin, what the Pentagon takes away with one hand it usually gives back with the other (and then some).

But the company’s biggest source of future growth is likely to be on the home front, where it is involved in everything from homeland security to the 2010 census. Lockheed Martin’s rapid move into the homeland security arena led to the company’s biggest fiasco in years, when it attempted to rebuild the US Coast Guard in the aftermath of 9/11. The programme to urgently upgrade the important but neglected Coast Guard was known as Deepwater, a $17bn initiative to build a small navy with over 90 new ships, 124 small boats, nearly 200 new or refurbished helicopters and aeroplanes, almost 50 unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), and an integrated surveillance and communications system.43

The first round of Deepwater failed so badly that it left the Coast Guard weaker and less capable. The winners of the Deepwater competition were Lockheed Martin and Northrop Grumman. The companies were to work in partnership not only to build their own aspects of the contract but to supervise the work of every other company involved in the programme. This ‘innovative’ approach was touted as a way to reduce bureaucracy and increase efficiency compared with a system in which the Coast Guard itself would retain primary control. What it ended up proving was that contractors can be far less efficient than the government at running major programmes. Anthony D’Armiento, an engineer who worked for both the Coast Guard and Northrop Grumman on the project, called it ‘the fleecing of America. It’s the worst contract I’ve seen in my 20-plus years in naval engineering.’44 Initially eight ships were produced for $100m. They were unusable: the hulls cracked and the engines didn’t work properly. The second-largest boat couldn’t even pass a simple water tank test and was put on hold. The largest ship, produced at a cost of over half a billion dollars, was also plagued by cracks in the hull, leading to fears of the hull’s complete collapse.

In May 2005, Congress cut the project’s budget in half, leading to the usual battery of letter writing, lobbying and campaign contributions that resulted in not only the avoidance of cuts to the disastrous programme but an increase to the budget of about $1bn a year, bringing the total project budget to $24bn. Finally, in April 2007, the Coast Guard took back the management of the project from the defence contractors. The first boats were expected to be ready for launch sometime in 2011, ten years after the 9/11 attacks that prompted the modernization effort in the first place.45

As is the way of the MICC, Lockheed has a chance to redeem itself through another ship-building project, the Littoral Combat Ship (LCS), a vessel designed to operate in offshore waters and to deal with ‘asymmetric threats’ such as pirates, drug runners, terrorists and small attack boats. After costs on early versions of the ship more than tripled, Robert Gates, the Secretary of Defense, restructured the programme to create a competition between Lockheed Martin and Northrop Grumman to win the rights to build the next ten ships. Ultimately, in December 2010, Lockheed Martin and Austal USA, the US branch of an Australian company, were awarded the contracts to build four ships initially, probably rising to ten ships by 2015.46 The total cost is estimated to be around $37bn.47

Deepwater is by no means Lockheed Martin’s only project concerned with domestic security. The company is the eighth-largest contractor to the Department of Homeland Security, including projects on airport screening and biometric technology. The latter is also used by the IRS, so that Lockheed not only keeps track of fingerprints but is also involved in processing tax forms, counting individuals in the census and sorting the mail.48

In 2010, the company received a $5bn contract to provide logistics services to US Special Forces in their deployment to Afghanistan and other areas of current or potential conflict. It is also getting a foothold in the market for UAVs, with a system based on blimps loaded up with cameras and sensors that can hover over an area and do surveillance without putting a pilot at risk.49

Lockheed Martin remains the US’s leading government contractor, with $36bn in federal contracts in 2008 alone, roughly $260 per taxpaying household – what Bill Hartung terms ‘the Lockheed Martin tax’. It is obviously the largest weapons contractor, with over $29bn in contracts from the Pentagon. And it has more power and money to defend its turf than any other weapons-maker. It spent over $15m on lobbying and campaign contributions in 2009 alone (excluding the contributions of its 140,000 employees), and the same again in the 2010 election cycle. The company ranks number one on the database of contractor misconduct, with ‘50 instances of criminal, civil or administrative misconduct since 1995’.50

In 2004, Lockheed Martin’s CEO, Robert Stevens, told The New York Times: ‘Our industry has contributed to a change in humankind.’ The question is whether for good or ill.

* * *

Despite President Obama’s acknowledgement that oversight of contractors to the government is inadequate, he has been unable to do much about it. One of the primary reasons is that, under the privatized military model, many of the outsourced contracts are managed by contractors as well, down to drafting the contracts and assessing the performance of other contractors. As a consequence, oversight of the hundreds of billions of dollars spent by the US military and its contractors is woeful.

Meaningful Congressional oversight of the Defense Department and defence contractors is severely undermined by the combination of cronyism, executive pressure on foreign purchasers, the revolving door and elected representatives’ desperate desire for defence companies in their states. In addition, national security is invoked to limit public scrutiny of the relationship between government and the arms industry. The result is an almost total loss of accountability for public money spent on military projects of any sort. As Insight magazine has reported, in 2001 the Deputy Inspector General at the Pentagon ‘admitted that $4.4 trillion in adjustments to the Pentagon’s books had to be cooked to compile required financial statements and that $1.1 trillion was simply gone and no one can be sure of when, where and to whom the money went.’51 This exceeds the total amount of money raised in tax revenue in the US for that year.

Remarkably the Pentagon hasn’t been audited for over twenty years and recently announced that it hopes to be audit-ready by 2017,52 a claim that a bipartisan group of Senators thought unlikely.53 If a developing country was run like this it would be prevented from receiving money from USAID or the UK’s DiFID.

A study by government auditors in 2008 found that dozens of the Pentagon’s weapons systems are billions of dollars over budget and years behind schedule. In fact ninety-five systems have exceeded their budgets by a total of $259bn and are delivered on average two years late.54 A defence industry insider with close links to the Pentagon put it to me that ‘the procurement system in the US is a fucking joke. Every administration says we need procurement reform and it never happens.’ Robert Gates on his reappointment as Secretary of Defense stated to Congress: ‘We need to take a very hard look at the way we go about acquisition and procurement.’ However, this is the same official who in June 2008 endorsed a Bush administration proposal to develop a treaty with the UK and Australia that would allow unlicensed trade in arms and services between the US and these countries. The proposal is procedurally scandalous and would lead to even less oversight but has generated little media coverage. In September 2010, with Robert Gates in office, the agreement was passed.55

The rigour of procurement accountability undoubtedly weakened in the post-9/11 environment and especially during the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan, where there has been a proliferation of non-traditional security programmes whose implementers believe they are exempt from normal requirements. The US Inspector General has said that with respect to Iraq and Afghanistan countless weapons and vast amounts of money are simply not accounted for. At least $125bn has been misused or is unaccounted for in the reconstruction of Iraq alone.56

In the past two years Iraq has signed arms deals worth more than $3bn. Amnesty International claims that there was no clear audit trail for 360,000 small arms to Iraqi armed forces, many from the US and the UK. In addition, about 64,000 Kalashnikov assault rifles have been sent from Bosnia to Iraq, while thousands of Italian Beretta pistols have been dispatched via the UK, many of which landed up in the hands of Al Qaeda insurgents in Iraq.57 A defence industry insider, who wished to remain anonymous, said to me: ‘The whole Iraq programme is corrupt to the core. There is no accountability. People are involved there because of connections not competence. These are connections in Republican circles. Just look at KBR.’ He continued: ‘Pakistan has also been given billions of dollars for fighting the Taliban, and there are huge transparency issues there as well.’

As a consequence of this lack of accountability and the Bush administration’s zeal to privatize as much of the military as possible, a number of fly-by-night operators landed huge defence contracts in Iraq and Afghanistan. The chaotic state of defence contracting reached its nadir with the procurement of ammunition for the Afghanistan security forces.

AEY Inc. was run out of a nondescript single room in Miami Beach, Florida, by Efraim Diveroli, a 21-year-old with a forged driving licence who had previously been arrested for domestic violence. His sidekick, David Packouz, was four years older, a drifter who had trained as a masseur. The two were serial party-goers, regular pot smokers who also dabbled in cocaine and acid.58 The company and its young president were on the State Department’s Arms Trafficking watch list. Nevertheless, in January 2007, AEY received a $298m contract with the US military as the main supplier of ammunition to the Afghan security forces.59

The US Army had asked for an independent evaluation of the company from a private individual, Ralph Merrill, who produced a glowing endorsement of AEY and Diveroli. It turned out that Merrill was a financial backer and a vice-president of AEY.60 The contract was vaguely written and contained few restrictions.61

Diveroli, wanting to purchase the ammunition as cheaply as possible, investigated Eastern European options, and found the cheapest prices and most malleable environment was Albania. As its post-war idiosyncratic, autarkic communist regime started to crumble in the early 1990s, Albania’s per capita quantity of weapons and ammunition was among the largest of any European country’s. The nation’s paranoid dictator, Enver Hoxha, gripped by the illusion of ‘an imperialist-revisionist invasion’, spent more on defence than anything else. Albania was completely militarized, awash with weapons and matériel and dotted with 600,000 concrete bunkers and fortifications for a population of just over 3 million. A great part of this armoury was of Soviet production. But in the 1960s and 1970s large quantities of Chinese weapons and ammunition reached Albania, Beijing’s close ally at the time. From the 1960s the country also produced its own ammunition.62

As the country emerged from communism, the State Security Service collaborated for years in weapons trafficking with the Italian mafia, Palestinian and Irish groups, among others. In 1991, Albania created an ‘autonomous’ enterprise to sell its stockpiles. Called MEICO (Military Export–Import Company) and headed by Ylli Pinari, it worked very closely with an iron merchant, Mihal Delijorgji, who was also the president of the Dinamo football club. Delijorgji had a history of problems with Customs and the courts. In 2004, he was arrested in the VIP section of the Dinamo stadium on charges of tax evasion. While under investigation he won a defence ministry tender to dismantle tanks and armoured vehicles. He eventually paid compensation of 122 million leks to Customs, and was found guilty of forgery of stamps and documents, for which he paid a fine. However, he engineered a ‘declaration of innocence’ from the Military Court of Appeal a year later.

He was always proposed by Pinari as a partner for foreign companies. The Army was Delijorgji’s golden goose, providing for senior individuals in the military and the defence ministry, as well as for Pinari, who owns real estate and apartments in Albania and a ‘luxurious house’ in Philadelphia.63

Albanian weapons were transported to Rwanda the year before the genocide, and sold into the Democratic Republic of Congo in 2005, and Sudan between 2004 and 2006. Albania sold weapons to the Israelis during the 2009 Gaza incursion and to Armenia, Georgia and Iran.64 While the amounts of arms may have been relatively small, this history displays a cavalier approach to the illicit arms trade which Efraim Diveroli was happy to exploit.

In 1997, when the country descended into anarchy after the collapse of a series of pyramid schemes in which many had invested their meagre savings, a number of the old arsenals were looted. The weaponry was used by organized crime gangs within the country and abroad, causing problems for Europe and the world. The UN and NATO, which was then contemplating Albanian membership, ran projects to dismantle, neutralize and destroy the arms and ammunition proliferating in the country. The most successful was conducted by a US firm, SAIC, a global leader in the decommissioning process and a company supported by Randy Cunningham. MEICO was involved in these efforts but, according to a senior worker in the main factory used, it was only there ‘for reasons of corruption’.65

MEICO realized there was significant money to be made in decommissioning, so contacted an American firm, Southern Ammunition Company Inc. (SAC). It is a small firm specializing in sporting guns. It can only be assumed that it was approached because an American firm offers good political cover in Albania and it happened to have initials very similar to the established US decommissioner, SAIC. Its president, Patrick Henry III, visited Albania a number of times, where he agreed on MEICO’s instructions, to form a joint venture with Mihal Delijorgji to create a company called Albademil. In return, SAC demanded that prices for ammunition should be fixed and the military should bear the cost of transporting the ammunition to the disposal site, which should be located close to Tirana.66

Albania’s Defence Minister, Fatmir Mediu, had met Patrick Henry in Tirana, and then pushed a decision through the Cabinet to allow a private company to take over the dismantling of the state’s ammunition. The Finance Minister at first opposed the decision, requesting a proper tendering process for the contract, but his opposition was overcome with assistance from the Prime Minister’s Office. When the Prime Minister signed the notice, it transgressed at least two Albanian laws. Mediu also created a state pricing authority which approved selling at the price Henry had agreed, although no payment was received from the company for the ammunition.67

In steamrolling the decision through Cabinet, Mediu made no mention of his and the businessmen’s plan to mobilize the army to collect and transport the ammunition at no cost. This would set the state back at least half a million dollars. Nor did he mention that the private contractor, with his approval, had refused to provide any guarantee of security against accidents, by far the most expensive aspect of disposal work. Mediu was accused of profiting from the contract. When this was revealed it caused little surprise. Close to the country’s President, and later Prime Minister, Sali Berisha, Mediu had been detained by Italian police at Milan airport in 1998, for harbouring among a delegation of MPs heading to an EU meeting on organized crime, and supplying with a bogus identity and a diplomatic passport, an Albanian underworld figure wanted in Italy for trafficking in prostitution and his leading role in an international drug-trafficking organization. Mediu was sentenced to three years in prison for assisting a fugitive from Italian justice. His sentence was confirmed in the Milan Appeals Court before being overturned by the Italian Supreme Court. Mediu was appointed Defence Minister by Berisha after elections in July 2005.68

The minister issued an order to allow the adaptation of an old tank base into a decommissioning factory at a densely populated village called Gerdec, situated conveniently between the capital and its international airport. The order made no mention of the transport requirements and the safety measures necessary for such a site. It had no licence for the storage and disposal of ammunition. Even the commander of the Joint Armed Forces suggested the site was inappropriate. Work at Gerdec was delayed by a few weeks, supposedly because of a visit to Tirana by George W. Bush. Albanian authorities seemed reluctant to alert the Americans to the operation that involved a US company. In April 2007, a company owned by Mihal Delijorgji began work to convert the site.69

Meanwhile Efraim Diveroli, having identified Albania as the cheapest and most conducive location for sourcing ammunition for Afghanistan, negotiated the knockdown price of $22 per 1,000 bullets with MEICO. When Diveroli pointed out that he was forbidden by US law from dealing in Chinese ammunition, he received photographs showing how easily the ‘Made in China’ markings could be removed. He would have to repackage the bullets, while MEICO would issue false certificates guaranteeing their Albanian origin. Pinari and Diveroli were fully aware that the bullets to be sent to Afghanistan would be up to forty years old, partly decomposed and largely unusable, and that many of them would be Chinese-made. A hundred million bullets were contracted for purchase.70

Diveroli entrusted the crucial repackaging process to the local packaging supremo, Kosta Trebicka. However, in June, as work was about to start at Gerdec, Pinari informed Diveroli that he would have to buy the bullets at $40 per 1,000 from a Cyprus-based firm, Evdin Ltd, and that Trebicka’s firm had to be replaced by Delijorgji’s company. Trebicka, who bravely revealed documents of the various transactions, showed that Evdin was a phantom company whose only purpose was to divert money to Albanian officials. The purchases were a flip: Albania sold ammunition to Evdin for $22 per 1,000 rounds and Evdin sold it to AEY for much more. The difference, he suspected, was shared with Delijorgji and Albanian officials, including Pinari and the Defence Minister, Fatmir Mediu.71 Importantly, the son of Sali Berisha, the Prime Minister, was alleged to have been involved in at least one meeting with Delijorgji and Pinari, leading to speculation that he too was in on the deal.72

Evdin was a company created by a Swiss arms dealer, Heinrich Thomet, who has been accused in the past by groups, including Amnesty International, of arranging illegal arms transfers under a shifting portfolio of corporate names. Thomet and Evdin are on the US State Department’s Defense Trade Controls watch list. Hugh Griffiths, of the Arms Transfer Profile Initiative, describes Thomet as a broker with contacts in former Eastern bloc countries with stockpiles and arms factories.73 An arms dealer since his teens, Thomet has been accused of smuggling arms into and out of Zimbabwe and was also under investigation by US law enforcement for shipping weapons from Serbia to Iraq.74 His proximity to AEY’s purchases raised further questions about whether the Pentagon was adequately vetting the business done in its name. ‘Put very simply, many of the people involved in smuggling arms to Africa are also exactly the same as those involved in Pentagon-supported deals, like AEY’s shipments to Afghanistan and Iraq,’ Griffiths said.75

Diveroli, aware of the corruption, went along with the new arrangements. In a conversation with Trebicka, Diveroli admitted: ‘Pinari needs a guy like Henri [Thomet] in the middle to take care of him and his buddies, which is none of my business. I don’t want to know about that business.’ Diveroli then recommended that Trebicka try to reclaim his contract by sending ‘one of his girls’ to have sex with Mr Pinari. He suggested that money might help, too. ‘Let’s get him happy; maybe he gives you one more chance. If he gets $20,000 from you…’ At this point, Diveroli appeared to lament his dealings with Albania: ‘It went up higher to the prime minister and his son,’ he said. ‘I can’t fight this mafia. It got too big. The animals just got too out of control.’76

While these machinations were being worked out, Delijorgji’s brother-in-law, Dritan Minxolli, the newly appointed supervisor at Gerdec, began employing people, including children. None of the employees received social security or health insurance. That summer through to October, Gerdec dismantled about 60 million bullets and removed from decades-old crates, washed, repackaged and dispatched to Afghanistan thirty-six consignments of falsely labelled bullets.77

Trebicka provided his revealing documents about the case to a New York Times journalist based in Tirana, Nick Wood. As Wood started ferreting around, all hell broke loose. Fatmir Mediu, seeking to cover his tracks, even visited the US ambassador for advice. The military attaché at the US embassy in Albania claimed that the ambassador, John L. Withers II, assisted the attempted cover-up of the Chinese origins of the ammunition. The ambassador met Mediu hours before Nick Wood was to visit the contractors’ operations in Tirana. The attaché, Major Larry D. Harrison II, attended the late-night meeting on 19 November 2007. He claims that Mr Mediu asked the ambassador for help, saying he was concerned that the reporter would reveal that he had been accused of profiting from selling arms. The minister said that because he had gone out of his way to help the United States, a close ally, ‘the US owed him something’, according to Major Harrison. Mr Mediu ordered the commanding general of Albania’s armed forces to remove all boxes of Chinese ammunition from a site the reporter was to visit and ‘the ambassador agreed that this would alleviate the suspicion of wrongdoing’, according to Harrison’s testimony to a House committee. The ambassador denied the allegations, claiming that all he advised Mediu to do was to issue a denial when any article was written.78 The Department of Justice cleared the ambassador, who has since retired, of involvement in covering up allegations of illegal activity.79

The New York Times stories led to an investigation of the scam and Diveroli was accused of a criminal scheme to sell banned Chinese munitions to the Pentagon and was indicted on federal fraud and conspiracy charges. He pleaded guilty in 2009 to a single conspiracy count and was sentenced to four years in jail.80 However, Miami federal prosecutors allowed the return of $4.2m of Diveroli’s property – including a new Mercedes S550 – that had been confiscated.

Because much of the equipment used by Iraqi and Afghan forces is of Soviet design and has to be sourced from a variety of former Soviet bloc countries, the standards applied to the procurement process by various US military commands and agencies, including the State Department, vary, as does the quality of the weaponry. Despite this reality, the granting of such a huge contract to so obviously unsuitable a company and individual beggars belief. Lax standards, virtually no vetting and contracting officers’ limited understanding of munitions all but ensured that the Army would end up with a disaster on its hands. The consequences for innocent Albanians would ultimately be far more deadly.

Feruzan Durdaj has lived in Gerdec since 1993 when he moved from an ancient village in the south of the country. His three children were all born in the village. He was proud of the house he had built them on the back of years of hard work. The village is poor, but close-knit, a community who rely on each other to get by. On the hill above Gerdec are five low bunkers of dirty concrete, Hoxha’s legacy. They are now used to house sheep and goats.81

On Saturday, 15 March 2008, Erison Durdaj, Feruzan’s seven-year-old son, could not sit still at home. He had finished his homework and rechecked it to the point of boredom. He was a bright child, chatty and full of energy. He loved nothing more than to career around the village on the sparkling new bike he had been given for his seventh birthday. His father was at work, his mother busy cleaning up the house. And his sister was annoyingly engrossed in a book. After one more glance at his homework he decided to visit his cousins, so grabbed his bike and set off for their house only fifty yards away. As he arrived at their gate his cousins Roxhens and Erida were just leaving to take their mother her lunch. He happily fell in beside them.

Erison’s aunt, Rajmonda, worked at the new factory in the village. In April 2007, work had begun at the dilapidated military base in the middle of the village and by June a prefabricated structure surrounded by a rickety fence had been built. Military trucks started to drive into and out of the site twenty-four hours a day. It was only when villagers were employed to work in the factory that they discovered its purpose, which was being undertaken in contravention of a number of environmental and safety laws and regulations. The villagers assumed it was a state-run factory, even though in the early days there were a number of Americans supervising the use of machinery. Dozens of unqualified men, women and children were soon employed. Every day crowds of unemployed people would congregate at the fence, anxious for work. The site manager would point to his selected candidates, those who appeared strongest, with a long stick, like a plantation owner at a slave market assessing the latest cargo from Africa.

It was dangerous work. One employee described how sometimes the bullets exploded, and the machines would catch fire. At first because the site only handled small-calibre ammunition, the fires could be easily extinguished, with only minor burns to a few workers. The casings and gunpowder were easy to take away.

Through the summer of 2007 and into September and October, about 60 million bullets were dismantled at Gerdec. Tens of millions of bullets were also repackaged into new boxes. In late 2007, the government granted permission for the factory to dismantle large-calibre ammunition, something at which none of the companies involved had any experience. The granting of this permission violated a host of further safety regulations, especially in relation to the distance of the operation from inhabited areas. In January 2008, the first 55 tons of large-calibre shells arrived at the factory. By mid-March, 8,900 tons of ammunition had been delivered to the site by a twenty-four-hour stream of military vehicles. One tenth of the entire ammunition arsenal of the Albanian armed forces was dumped at Gerdec.

Workers came from surrounding villages to take advantage of the increased activity. The work involved removing the component parts of the shells from the crates, setting to one side the fuses and projectiles, and then opening the casing, from which the detonators and gunpowder were removed. This was all undertaken in the most primitive way, by hand. The only mechanized equipment at the site was a military bulldozer, which pushed the piles of projectiles towards the nearby field. They filled two fields of about 2,000 square metres. The gunpowder was put into sacks, the detonators into crates and taken to one of the buildings of the old military base. The shells were washed with detergent and oil. The women who cleaned them were also responsible for cleaning assembled shells, which were so ancient that workers found mould and mice inside the crates in which they arrived. These cleaned, assembled shells would then be taken from Gerdec, while hundreds of tons of gunpowder and thousands of detonators and dismantled shells were left behind.

On 12, 13 and 14 March, army trucks had unloaded more than 460 tons of shells at Gerdec. There were more than 1,000 tons of gunpowder, over 286,000 detonators and almost 4,400 dismantled or intact shells, containing about 800 tons of TNT. Thousands of projectiles had been pushed aside by the bulldozer or carried to the field, and those that the women in the cleaning shed had recently washed were stacked there in piles. Gunpowder filled all the available containers and a large part of the main shed and was left in unsealed plastic bags around the open area where workers were dismantling shells. The casings hadn’t been removed for ten days.

The Durdaj cousins set off towards the factory, which was not 200 yards from where they played. They arrived at the gate within five minutes. The guard told them they couldn’t go into the factory but that he would give Rajmonda her lunch. ‘Be careful not to spill anything,’ Roxhens told the guard, ‘because there are some olives in brine.’ The guard nodded and walked away. The children set off to play. Erison jumped over a ditch in the field and stopped to mount his bicycle. Roxhens turned round to see why his cousin had fallen behind. He saw a huge ball of smoke and fire, resembling a gargantuan rose, opening behind Erison’s back with a deafening roar. ‘Eri, Eri, Eri,’ he screamed, as the deadly flower enveloped them all.

Feruzan was at work in Tirana, when at 11.55 his wife called to say there had been an explosion. He screamed into his phone: ‘Run, run far away with the children.’ His wife told him that she had two of the children, but Erison was out playing with friends. He raced to the village. The police stopped him entering the village, so he found another route to his home. On the road he met his wife and two older children. His daughter was crying still because of a projectile that had exploded in front of them. He crammed eight people into his car and took them to the hospital, then raced back to find his son. They wouldn’t let him back into the village. He returned to the hospital to look there for Erison.

At 4 p.m. a cousin told him that his son was in hospital in Tirana. He sped to the capital and scoured the hospital. He walked straight past his youngest child without recognizing him. His wife found the little boy. ‘I was playing. I don’t know where the fire came from,’ he managed to say, between sobs. When Feruzan saw him, he lost all hope. He was so badly burned. ‘I’m really sorry I went out without permission,’ Erison said, quietly. The next day Feruzan took Erison to a hospital in Italy. He was only allowed to watch his son’s agony through glass. At 3 a.m. on the morning of the eighteenth day, they told Feruzan that his son had died. He never heard him speak another word.82

In the explosions, which continued until 2 a.m. the following day and were heard more than 100 miles away, Feruzan also lost his sister-in-law, Rajmonda, along with twenty-four other villagers. One member of the extended family who lived in the house nearest the factory miraculously survived. Uran Deliu lost his mother, father and three-year-old son, his pregnant wife, his brother and his brother-in-law, who was only at the house by chance. Over 300 people were injured, 318 houses were completely destroyed and almost 400 others damaged.83 The figures would have been even worse had many villagers not been out and about, and if hundreds of others had not managed to flee up the hill, some into Enver Hoxha’s surreal bunkers.

Six months after the Gerdec explosion, the body of the whistle-blower Kosta Trebicka was found near Korçë. He appeared to have died in a car accident. However, contradictory evidence surfaced to cast doubt on this claim, especially given the threats he had received since exposing the corruption and criminal negligence at Gerdec.84 Whatever the cause of his death he too was a victim of this criminality.

Standing on the hill above the village, where the skeletal remains of two houses stand unmended by the villagers as symbols of their suffering, I asked Feruzan what life was like in Gerdec over two years after the explosion. With goats wandering into and out of the derelict concrete bunkers and villagers nodding in agreement, this handsome, dignified and pained man replied: ‘It is like living every minute of every day in a cemetery.’

* * *

If the Departments of Defense and State are so patently inadequate at vetting and controlling contractors and Congress is abject at oversight because of its own compromised position, that leaves the Department of Justice (DOJ), its sub-agencies, and the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) as the bulwark against arms trade anarchy. The DOJ has limited resources and varying levels of enthusiasm for investigations into arms deal corruption.

I gathered this when meeting a senior anti-corruption officer in the FBI in late 2008. I waited for him outside the J. Edgar Hoover Building on Pennsylvania Avenue, an imposing, if dour edifice. He had approached me as a consequence of my work on the South African arms deal to ask if I knew anything about corruption in the US defence industry. A tallish man, younger than I had imagined from his telephone voice, approached the bench I was sitting on and indicated for me to follow him. We walked six long blocks before he stopped outside a small, obscure coffee shop.

We sat in a dark corner. He was nervous. He spoke in a torrent, his frustration palpable. ‘Look at Nigeria. Look at an American company called W. They engage in corruption but it’s regarded as small scale. They never sign a contract of more than $50m to $70m. On each one they pay bribes of between $1m and $2m. Deals of this size are never investigated, we don’t have the capacity. It’s only if they do ten or fifteen deals like this that we will get interested. We can only focus on the big contracts because there are never enough people working on FCPA [Foreign Corrupt Practices Act] cases on arms or the military broadly.’ He suggested that, despite the legislation, corruption in arms contracts is substantial.

We agreed to remain in touch and to exchange information on a regular basis.

As the source confirmed, the FCPA was not rigorously enforced for its first two and a half decades. From 1977 to 2001, only twenty-one companies and twenty-six individuals were convicted for criminal violations of the legislation.85 In 2002, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) concluded that ‘the number of prosecutions and civil enforcement actions for FCPA actions has not been great’.86 However, since 2002 there was an increase of cases as a consequence of improved resources and the formation of a new dedicated five-member FCPA enforcement team, which has expanded several times since.87 At one point there were sixty cases being investigated. Even if they were not all carried through, it suggests greater enforcement than thirty cases prosecuted in almost thirty years. At the end of 2009, the DOJ and SEC were between them investigating 120 FCPA cases.88 There has also been an increase in consolidated investigations, where multiple companies are investigated for multiple activities.89 While this is a definite improvement it is still a very small number.

In enforcing the FCPA, both criminal and civil sanctions are used. The SEC uses fines and often disgorgement of profits for corrupt deals, while both the SEC and DOJ have moved towards settlements and deferred and non-prosecution agreements in dealing with offenders. They argue that this is more effective than the long, complex and expensive court processes in establishing the guilt of offenders and that such agreements are effective in obtaining structural reforms within offending organizations.90 An FCPA prosecution can, but seldom does, result in loss of export privileges and debarment from US government contracts.91

For the 1978–2002 period, of a total of thirteen cases initiated by the SEC, two were dismissed or disposed of without sanctions. Indeed between 1978 and 1996 in seven of the thirteen cases no fines or penalties were imposed, most were resolved with an injunction, a legal slap on the wrist. For a period of at least ten years no actions were brought by the SEC under the accounting and record-keeping provisions of the FCPA.92 Where fines were imposed they were generally very small.93 Corporate fines for 1978–2001 ranged from $1,500 to $3.5m, with the exception of Lockheed, whose settlement amounted to $21.8m in 1994. Individuals in the same period received fines of between $2,500 and $309,000 and until 1994 no jail sentences were imposed.94

Lockheed’s settlement related to its operations in Egypt, where between 1980 and 1990 Dr Leila Takla was their consultant, responsible for the development of markets and sales. In 1987, Takla became a member of the Egyptian Parliament, where she used her influence with the Ministry of Defence to direct business to Lockheed, specifically to ensure it received a contract for three C-130 aircraft. During the contract negotiations, Suleiman Nassar, the regional vice-president for Lockheed International, agreed to make monthly payments to Takla. The payments, which totalled $129,000, were wired from Lockheed to a corporation known as Takla Inc. whose signatory was Takla’s husband, a police general. In addition, the company submitted fraudulent statements regarding the bribes to the Defense Security Assistance Agency. Ultimately, Lockheed was awarded a contract worth $78,983,575. After it was signed, the company paid Takla $1m as a commission.95 She was a board member of the Suzanne Mubarak Women’s International Peace Movement, chairperson of the UN Voluntary Fund and President of the Union of the World’s Parliament.

The corporate collapses of Enron, Worldcom, Tyco International, Peregrine and Adelphia as well as the bursting of the dotcom bubble compelled legislators, in response to a backlash from their constituents, to attempt to clean up both the US’s illicit extra-territorial adventures and the corporate shamanism that had come to dominate markets. This led to the International Anti-Corruption and Good Governance Act of 2000 to stop US companies bribing foreign governments or officials and the Sarbanes Oxley Act (SOX). The government announced that white-collar crime would be a greater focus of the ‘War on Crime’, causing a sea-change at the SEC and DOJ. An increased focus on money laundering in the War on Terror and enhanced powers for surveillance and tracking of money movements made possible by the Patriot Act also contributed.

While this legislation didn’t amend the FCPA, it significantly increased possible penalties. It also enhanced the transparency requirements for corporate accounts and imposed higher levels of due diligence and better auditing standards. CEOs and CFOs face penalties of up to $5m and twenty years’ imprisonment for serious violations. The threat of these penalties certainly had some impact.

In recent years there has been an increase in investigations and prosecutions under the FCPA, and big corporations seem not to be immune. Large companies have been investigated and joint investigations more willingly carried out. Recent large FCPA investigations by the US government have also been likely to include parallel investigations in other countries, such as the UK in relation to BAE and France and Nigeria with respect to Halliburton. There have also been increases in the severity of penalties. In early 2009, KBR was hit with a $402m fine and along with its former parent company, Halliburton, a $177m disgorgement payment.96 And, as we know, BAE finally agreed to pay $400m for lying to the US government over its corrupt dealings in Saudi Arabia and Eastern Europe.

The penalties for these offences, while far higher than was historically the case for FCPA violations, have never been truly commensurate with the scale of the corruption. For example, BAE’s bribery campaign for Al Yamamah in Saudi Arabia may have involved as much as £6bn in corrupt payments, as part of a deal worth an estimated £43bn. By comparison, a $400m fine is negligible. Just days after the BAE settlements were announced, the company received a £261m pension windfall, almost compensating for the value of the entire fine. BAE also announced profits of £2.2bn on sales of £21.5bn for the year.97 Mike Koehler, a business law professor at Butler University, noted wryly: ‘Any time someone settles a case for $400 million or $180 million, you’re like “Wow – they really got hammered!” But when you go through the DOJ’s own allegations and add up the amount of the bribe payments and the amount those bribes caused the companies to get in business, you’re still in a situation where they come out net positive.’98

What is the aim of these penalties? Should the intention be to penalize the company even if it could precipitate its collapse? To what extent is it fair that shareholders and employees who knew nothing of any bribery should lose their money or jobs? Should governments debar companies from future public sector contracts for periods of time linked to the severity of the offence even though it may threaten the industrial base or in the case of the MICC the perceived national security interest? To what extent should companies bear responsibility for the actions of individual employees and how much should an employee be penalized for their part in corporate corruption?

Judging the severity of a penalty is made even trickier by the lack of information available on FCPA cases. They are rarely aired in public, most being settled out of court so that the companies do not have to deal with weeks of bad headlines and large lawyers’ fees. Instead, most companies choose to come clean and at least appear to make a fresh start, firing anyone clearly tied to a crime and requesting lenience for the company, as Lockheed did with Kotchian and Haughton. While arguably making the lives of investigators and companies easier, this inhibits transparency, making external scrutiny by the public impossible. There is a compelling argument that without an ongoing understanding of the application of the law, no democratic process can be sufficiently informed to improve or change the law for the better.

Companies often plead guilty and cooperate with FCPA investigators once it’s clear that investigators are able to substantiate allegations against them. The opposite is remarkably rare but occurred in the BAE case. Investigators reacted to the company’s lack of acknowledgement of guilt or cooperation by apprehending BAE executives Mike Turner and Nigel Rudd at US airports and copying the contents of their laptops, phones, PDAs and papers before allowing them to proceed. This power to examine and copy any data brought into the country was granted to US investigators under War on Terror rules to facilitate detection of potential terrorism plots, as well as other crimes such as child pornography and copyright infringement.99

The FCPA operates on the principle of respondeat superior; that is, if one employee is guilty of bribery, even an employee acting only at a low level or against official company policy, then the entire company can be found guilty of the crime. This requires only a minimum of evidence to substantiate a claim of bribery on which to convict the company.100 The Financial Reform Bill – officially called the Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act – passed in July 2010, contains provisions for whistle-blowers to receive a cut of any settlement or penalties from companies violating the FCPA. The SEC will pay whistle-blowers at least 10 per cent and up to 30 per cent of monetary sanctions in excess of $1m, awarded in a successful enforcement action. Given the size of recent FCPA settlements, the incentive to inform on a corrupt company has been greatly increased.101

It is obvious that there are more instances of bribery and corruption in the arms trade than ever make it into the media. Most malfeasance remains hidden behind the veil of national security while some companies do self-report and put in place remedial steps that cause the DOJ or SEC to decide that justice has been served.102 But in the cases of BAE and KBR/Halliburton there was definite intention to hide the illegal behaviour.

BAE’s Mike Turner famously told the SFO that the reason for the company’s extensive web of secret offshore companies used to launder bribe money was to ensure commercial confidentiality and to avoid intrusion by the media and anti-arms campaigners.103 This systemic, intentional and long-running effort to hide payments with the complicity of executives who clearly knew what they were doing was illegal, and deserved a far greater penalty.

In the KBR case, Technip paid bribes to Nigerian officials using agents via shell companies in Gibraltar and Japan with the authorization of senior executives.104 Technip was fined $240m in settlement and $98m in disgorgement of profits.105 While this was again a significantly larger fine than in the earlier years of FCPA enforcement, it was hardly damaging to the company, as Technip made a profit of €417.3m in 2009.106 The corporate structure was, according to investigators, ‘part of KBR’s intentional efforts to insulate itself from FCPA liability for bribery of Nigerian government officials through the Joint Venture’s agents’. The company’s executive chairman, Albert ‘Jack’ Stanley, received a seven-year jail sentence. Two UK citizens, Jeffrey Tesler and Wojciech Chodan, who were indicted in the United States for their alleged participation in the scheme and arrested in the UK, face extradition to the US. Why there was the motivation to prosecute individuals in the KBR case but not BAE is perplexing.

While there has been an increase in prosecutions of individuals – in 2009 there were three trials of four individuals in FCPA cases, equalling the number of trials in the preceding seven years107 – this still unimpressive figure does not include anyone from the large defence companies, suggesting that bribery and corruption are still more tolerated when it comes to the commanding heights of the weapons business.

The closest a company has come to debarment was the temporary suspension of BAE’s US export privileges while the State Department considered the matter.108 Specific measures seem to be taken to avoid applying debarment rules to major arms companies, in particular by charging companies with non-FCPA charges as in the case of BAE.109 A legislative effort was undertaken to debar Blackwater (Xe) from government contracts due to its FCPA violations. Legislation was introduced in May 2010 to debar any company that violates the FCPA, though with a waiver system in place that would require any federal agency to justify the use of a debarred company in a report submitted to Congress.110 The mutual dependence between the government, Congress and defence companies means that, in practice, even serial corrupters are ‘too important’ to fail. For example, the US could not practically debar KBR, a company to which it has outsourced billions of dollars of its military functions. Similarly, debarring BAE would threaten its work on new arms projects and the maintenance of BAE products that the US military already uses.

Some argue that it would be unfair to impose so massive a penalty on companies that depend almost entirely on government contracts, as arms companies do. Within these huge companies, very few are guilty of involvement in bribery and workers and shareholders should not be punished for the crimes of a few executives. However, the status quo is, in a way, a golden get-out-of-jail card for the arms business, and suggests that even serial corrupters are immune from punishment that will seriously threaten their business.

Smaller operators are far more likely to face grave consequences for illicit arms dealing, especially since the enforcement of the FCPA underwent a revolution a few years ago with the use of sting operations in arms cases. Stings have generally been associated in the public mind with catching drug dealers. However, while they have been used against arms dealers for many years by journalists, more recently the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) and DHS have adopted the practice.

* * *

Sting operations by US law enforcement agencies have been used in the cases of Monzer Al-Kassar, Viktor Bout and Amir Ardebili, an Iranian arms procurer.111

The sting against Ardebili was planned and undertaken over four years by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), a division of DHS, which set up a number of mock arms businesses to entrap the Iranian arms purchasing network.112

John Shiffman, the journalist who revealed the operation in the Philadelphia Inquirer, describes the Iranian in question as a freelance arms broker who used the internet to buy embargoed matériel from US contractors for his only client, the Iranian government.

Ardebili was an ordinary man in his late twenties, living with his parents in the city of Shiraz. His first taste of the arms trade had come via his low-paid job with a state-run company. There he placed orders for embargoed weapons with Iranian brokers who would source it from international companies, especially in America and Europe.

Shiffman outlines the complex logistics used to move this contraband. As is common in the shadow world, the goods were shipped from the US to a safe destination, usually somewhere in Europe or the Middle East – Amsterdam, Dubai and Beirut are often used. At this second port the goods would be re-labelled, sometimes even re-packaged, and shipped as a new order to the contact in Iran, who would pass them on to the state company, which in turn made them available to the Iranian armed forces.

Despite being very good at what he did, Ardebili earned a paltry $650 a week. Motivated by a desire to make more money, in early 2004 he went into business for himself. His previous employers and other state-run entities were happy to use his services as a middleman. He created an online identity: known as ‘Alex Dave’ he gave a forwarding address in Dubai. Interestingly, as Shiffman points out, the young Iranian kept his location secret and his American suppliers seldom bothered to enquire. Over time, he established a growing network on his own account, and before long he had a burgeoning business.

The ICE agent who drove the operation against Iran was Patrick Lechleitner. On the basis of a varied law enforcement career he was well placed to lead the complex, expensive and risky operation.

Lechleitner set himself up as a weapons broker with an online presence. He searched the internet for suspicious queries and developed a network among US defence contractors who interacted with foreign traders.

And so the scene was set.

Shiffman describes how, in April 2004, Lechleitner was approached by a local factory owner who was suspicious of an enquiry he received from Dubai for parts for a fighter jet. ‘He seemed almost offended by the bluntness of the email,’ Lechleitner told Shiffman. The agent and contractor were both suspicious of the request, suspecting it was not from Dubai but from Iran.

With a collapsing military infrastructure that is predominantly American due to massive US sales to the Shah, Iran, whose military and nuclear ambitions are currently the cause of great concern in the West, is constantly in need of US hardware, and not just spare parts but also all the equipment, weapons and technology required for modern warfare. In addition, the US claims that the theocracy of Holocaust-denying President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad is not only a threat to Israel but also provides matériel to a number of America’s enemies, including the Taliban, Hezbollah and insurgents in Iraq and Afghanistan.

With this request, Lechleitner smelled a promising lead. He encouraged the US contractor to persuade the Iranian to make contact with the mock ICE company. Such circuitous referrals are common practice in the world of illicit arms dealing and would not have raised suspicion.

Over a period of time the agent noticed that the Iranian was submitting increasing requests for equipment. According to Shiffman, Alex Dave’s frenetic activity led to a US agent remarking: ‘The guy’s got so many quotes, he’s like Shakespeare.’ Thereafter Ardebili was known as Shakespeare and the case referred to as Operation Shakespeare.

As the bard’s activity intensified, ICE decided to make its move. They involved another undercover agent, ‘Darius’, who had established a fake US arms company in a Baltic country. This was one of eleven such overseas ‘storefronts’ created by the CIA at a cost of $100m, and was to be the only one that would produce results.

ICE arranged for a British broker to recommend Darius to the Iranian. Contact between the two was established, and a chain of events that was to lead to Ardebili’s eventual arrest was set in motion.

When Alex Dave requested night-vision equipment during phone calls with Darius, the latter feigned concern about US embargoes and the illegality of the transaction. Ardebili immediately tried to put him at ease, describing the trans-shipment process he had perfected to keep his Iranian origin hidden. He assured his new supplier that he had undertaken similar transactions many times with no problems.

After months of communication they finally arranged to meet in Tbilisi, Georgia.

US agents arrived in the Eurasian country with microchip radar units and gyroscopes, which the Iranians had requested. They filmed Ardebili acknowledging the extensive business he had done and hoped to do in the future, before arranging his arrest by Georgian police and the seizure of his laptop.

After a few tense months characterized by complicated negotiations, Ardebili was extradited from Georgia and flown to the US to face trial.

In the meantime, US agents gleaned an astonishing amount of information from Ardebili’s laptop. Shiffman has reported that the laptop enabled the DHS to identify seventy American contractors illegally trading arms with Iran, sixteen of whom did significant business with the Pentagon. They discovered thirty-three bank transfers routed from Tehran via Europe to American defence companies and were able to identify over twenty Iranian purchasing agents and around fifty Iranian government entities procuring matériel for the country’s military.

While Shakespeare was secretly detained in a Philadelphia prison, DHS agents posed online as the arms broker from Iran, resuming negotiations as Alex Dave with 150 US companies. This secret operation was now one of DHS’s largest investigations. They netted around twenty companies from across the US, Dubai and Europe who were illegally selling military or restricted technology.