18. Making a Killing: Iraq and Afghanistan

The decision to go to war in Iraq was the culmination of the life’s work of many people in the Bush II administration: an outcome prompted by the exhortations of Prince Bandar and the unwavering support of Tony Blair. It had enormous consequences for the US, for the Iraqi people, for geopolitics and for the arms trade. Arguably, they were mostly negative, except for the bonanza it provided to arms dealers, weapons manufacturers and the providers of military services. They made a killing.

Iraq and its ‘liberation’ unsurprisingly interested Lockheed Martin’s Bruce Jackson, both as a neocon and as a businessman. Although he left Lockheed Martin in 2002, his ten years with the company shaped his approach to national security as he continued to take actions that benefited his former employer. As a co-founder of the Committee for the Liberation of Iraq (CLI), Jackson worked directly with the Bush administration in marketing the war. In fact, he claims that the White House asked him to ‘do for Iraq what you did for NATO’.1 He drafted a letter signed by ten Central and Eastern European leaders endorsing an invasion of Iraq, right after Colin Powell’s misleading presentation on the US case for war to the UN.

He was so wired into the hawkish think-tanks that one prominent neocon described him as ‘the nexus between the defense industry and the neo-conservatives. He translates them to us and us to them.’2 His job was eased by the number of his Project for the New American Century colleagues in prominent roles in the Bush administration, all of whom were early proponents of the invasion and misled the American public to justify it.

In addition to building up the PNAC’s advocacy for greater military might and bigger budgets, Jackson’s efforts to promote intervention in Iraq were substantially aided by the CLI, which he had helped found. One of the most vociferous media supporters of intervention was the retired General Barry McCaffrey, who worked as a consultant for NBC in the lead up to and after the invasion. He appeared over 1,000 times extolling the necessity of invasion and the virtues of the war. What was never mentioned was that he earned hundreds of thousands of dollars as a consultant to defence contractors seeking to profit from the Iraq War. An exhaustive New York Times investigation put McCaffrey at the centre of a Pentagon-orchestrated plan to get retired military officials – many with ties to the defence industry – to use their numerous media appearances to promote the administration line on the war. They received special Pentagon briefings to inform their commentary. In mid-2007, McCaffrey signed up with a company, Defense Solutions, to help it lobby for a contract to deliver used armoured vehicles from Eastern Europe to forces in Iraq.3

Despite this media onslaught the administration was not able to convince the majority of Americans of the purported link between Saddam and Al Qaeda, let alone convince them of the Weapons of Mass Destruction (WMD) argument, which Paul Wolfowitz admitted in Vanity Fair was the approach decided on because it was considered the best way to sell the war to the American people.4 Even after definitive proof that the WMD did not exist in Iraq the PNAC clung to the justification, publishing a report in April 2005, Iraq: Setting the Record Straight, which argued that there might still be WMD in Iraq.

Chuck Spinney argues that the intertwining of defence companies like Lockheed Martin, their allies in government, think-tanks and the Pentagon not only results in profligacy from $600 toilet seats to the $70bn spent on unrequired F-22s, but it also makes war more likely, due to the combination of interests and the dominance of the executive over the legislature. The President has gained more and more power, which gives him ever increasing patronage. The executive branch is able, in myriad ways, to control money going to Congressional districts, directly (through supporting weapons programmes) or indirectly (through all of the government agencies). And patronage is now crucial given the cost of elections. It is extremely difficult for a Representative with defence production in his or her constituency to oppose a President going to war. It is for this reason that West Virginia’s Senator Robert Byrd remarked in February 2003, as the Iraq War inexorably approached:

As this nation stands on the brink of battle, every American on some level must be contemplating the horrors of war. And yet this chamber is for the most part ominously, ominously, dreadfully silent. You can hear a pin drop. Listen. There is no debate. There’s no attempt to lay out for the nation the pros and cons of this particular war.5

Lockheed Martin and Halliburton were the two biggest beneficiaries of the war. The former received 25 billion US taxpayer dollars in 2005 alone. This sum exceeded the GDP of over 100 countries and was larger than the combined budgets of the Departments of Commerce, the Interior, Small Business Administration and the entire legislative branch of the government. Lockheed’s stock price tripled between 2000 and 2005. The Defense Index went up every year from 2001 to 2006 by an average of 15 per cent, seven and a half times the S&P average, and these companies were among the most resilient in the credit crisis. Lockheed was also the biggest spender on political campaigns among the arms manufacturers who contributed almost $200,000 to the Bush ’04 campaign.6

* * *

The US, and other allies in the invasion, had a long history of support for Saddam, including providing him with financing, weapons and matériel. This despite his authoritarian, repressive rule since assuming absolute power in 1979, symbolized by his brutal genocide of Kurds in the north of the country which led to between 50,000 and 100,000 deaths, and included the largest chemical attack on civilians in history, at Halabja.7

The Arab Socialist Baath Party had overthrown the country’s military government in 1968, with Saddam becoming President in 1979. He was supported by the US and the West because of his government’s secular nature and general friendliness towards Western companies. He was also a crucial bulwark against the theocratic regime in Iran which had overthrown the American-supported Shah.

Saddam’s Iraq, where Sunni occupied most positions of power over a Shi’ite majority, was concerned when the ruling Sunni minority was overthrown by the Shi’ite majority in Iran. In 1980, using claims over a disputed waterway,8 Iraq declared war on what was believed to be a weakened Iran so soon after its revolution.9 The Iran–Iraq War lasted from September 1980 to August 1988, claiming the lives of at least half a million people.10 The war ended in a stalemate, partly due to covert and overt arms sales from Germany, Britain, France and especially the United States.11

On 4 August 1989, FBI agents raided the Atlanta offices of Banca Nazionale del Lavoro (BNL), which is headquartered in Rome. On a tip-off from two company insiders, the FBI seized thousands of documents that, when stitched together, would conclusively prove that the US had been funnelling money to Saddam Hussein.12 Over the next three years, Representative Henry B. Gonzales sifted through the documents attempting to reconstruct exactly what had happened, despite the constant intervention of the George H. W. Bush White House, terrified of the implications of the scandal. By 1992, the picture had become clearer: BNL had become Saddam Hussein’s largest creditor, sending over $5.5bn in loans to Iraq from 1985 to 1989 with the help and complicity of the CIA and Washington power players.13 The loans had been guaranteed by the US government, using the cover of the Commodity Credit Corporation, an agricultural loan facility used to promote the export of US food produce around the world. When Iraq later defaulted on the loans, it was the US taxpayer who picked up the tab.14

The money raised from the BNL scandal was central to the military ambitions of Saddam Hussein’s regime – and that of the US itself. During the drawn-out war between Iraq and Iran, Washington claimed neutrality. Covertly, however, deals were made with both sides. Under the auspices of Oliver North’s illegal Reagan-supported, Israeli- and Saudi-aided project the US diverted weapons to Iran, in what would become known as the Iran–Contra scandal. But, for the most part, the administration’s decisions tilted to Iraq and Hussein, as the US worried about the implications of Iran’s religious aversion to the West. Certainly the monetary support Hussein received was far in excess of that given to Iran. With the money at its disposal, Iraq embarked on a weapons-buying spree, purchasing billions of dollars in arms, mostly from Europe.15 The US not only made the money available, but also allowed tons of ‘dual-use’ items into Iraqi hands, including valuable virology material that aided in the production of biological weapons.16

From 1980 to 1990, Saddam spent at least $50bn on conventional weapons and close to $15bn on covert weapons programmes, both nuclear and biological.17 While the US was careful not to export any conventional arms, it did provide about $1.5bn in dual-use items, many explicitly for use in these covert programmes. Between 1985 and 1989 alone, the General Accounting Office found that the US Commerce Department approved 771 dual-use exports to Iraq.18 The list of dangerous chemical concoctions that were sold at the time makes for chilling reading: ‘Sarin, Soman, Tabun, VX, Cyanogen Chloride, Hydrogen Cyanide, blister agents and mustard gas’, according to the journalist Stephen Brown. ‘Anthrax, Clostridium Botulinum, Histoplasma Capsulatum, Brucella Melitensis, Clostridium Prefingens and E Coli’ rounded out the list of biological agents.19 A more conventional deal was the purchase of sixty helicopters for Saddam from manufacturers Bell, McDonnell Douglas and Hughes. Technically, the choppers were sold for use in agricultural spraying. In reality, they were militarized as soon as they entered Baghdad. Perhaps their intended use would have become clearer to the Department of Commerce if they had paid attention to the man who was brokering the deal on behalf of Iraq: Sarkis Soghanalian.20

Soghanalian was one of the most notorious arms dealers of the Cold War era. Born in Syria in either 1929 or 1930, Soghanalian was raised in Lebanon. He later joined the French army in 1944, working in a tank division. He was to spend the rest of his life around sophisticated weapons. He started his arms-dealing business in earnest in the early 1970s, becoming actively involved in supplying US weapons to the Lebanese government. Soon after, Soghanalian moved to the US, where he settled permanently and made a number of key connections in the CIA and FBI. Prior to working in Iraq, he provided weapons to numerous regimes with the active support of the CIA. These included Nicaragua, Ecuador, Argentina and Mauritania. Other notable clients included Libya’s Muammar Gaddafi, to whom Soghanalian sold a C-130 transporter plane in 1987, and Zaire’s Mobutu Sese Seko.21

His biggest deals, however, were in Iraq, where he was reported to have overseen $1.6bn in arms deliveries to the country. Despite claiming he was acting with the blessing of the CIA, he was arrested and convicted in 1991 of exporting arms to Iraq without federal licences. Initially given a six-year sentence, Soghanalian had his term reduced to two years after agreeing to help the FBI bust a counterfeiting ring in Lebanon producing $100 notes. One of his most notorious post-Cold War deals involved an air drop of 10,000 AK-47s into Peru, allegedly with the knowledge of the CIA. The arms were subsequently transported into Colombia where they were sold to the FARC. In 2001, he was convicted once more for cashing fraudulent cheques, although he was released immediately on the advice of the US Attorney General, who claimed that Soghanalian was assisting with an unnamed investigation.22

The UK, too, played its part in supplying multiple dual-use items to Iraq. Technically, the UK had banned the exportation of ‘lethal’ items to the country from 1984 onwards, although it allowed many questionable ‘non-lethal’ products through Customs. These sales included sophisticated electronics, military Land Rovers, uniforms, military radars and machine tools.23 Trading relations were good enough for Iraq even to buy into UK companies. In 1989, Iraq purchased the Coventry-based Matrix Churchill, whose board then featured two members of the Iraqi security forces. Matrix Churchill was one of the most respected machinist firms in the country and supplied sophisticated parts and machines that helped Iraq establish its own indigenous arms-manufacturing capacity.24 In 1992, two directors of Matrix Churchill were prosecuted for violating Customs regulations. The case, however, collapsed when it was discovered that the company had been making the sales with the knowledge and implicit help of the Conservative Party.25 In 2001, the two directors received substantial payouts in compensation for being wrongfully prosecuted.26

For its conventional weapons, Iraq was able to enlist the services of nearly every country. Answering the question: ‘Who armed Saddam?’, Anthony Cordesman, an expert on the Iraqi military, answered bluntly: ‘everybody who has arms’.27 By far the largest numbers of weapons – the basics such as AK-47s – were imported from the USSR, which accounted for just over 50 per cent of the trade with Iraq.28 The rest was made up from various countries, with France and Germany the two most important European suppliers. German companies and scientists were deeply involved in Iraq’s ballistic missiles programme, providing technical goods and specialist advice. French companies such as Dassault, Thomson-CSF and Aérospatiale, meanwhile, made considerable sums of money by selling a vast array of weapons to Saddam.29 Between 1979 and 1990, France exported dozens of Mirage F-1C fighters, 150 armoured cars, numerous Puma and Gazelle helicopters, 2,360 surface-to-air missile systems and over 300 super-powerful Exocet anti-ship missiles.30 In 1989, Saddam hosted the first ever international armaments fair in Baghdad. France mounted the largest display of French weaponry seen outside the country for decades.31

But, a year after the BNL scandal erupted, Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait, a staunch US ally. The man the US and the world had helped arm was now enemy number 1. Arms trade blowback once again.

The US, led by President George H. W. Bush, repelled Iraq’s army, sweeping away Saddam’s million-man force with remarkable ease. Thirteen years later, George W. Bush took on Saddam again, launching an invasion that, it was hoped, would remake the world. The two wars could not have been more different: the US operation in Kuwait in 1990 was backed by the international community and undertaken with a UN mandate. In 2003, much of the world looked on in horror as Bush Jr ignored the protestations of the UN. Millions marched around the world beseeching the US to change its mind. Most importantly, it was a war fuelled by an ideological impulse to assert American hegemony and remodel the world to its strategic imperatives. And it was undertaken largely by private companies.

The result has been a windfall for the companies involved in the business of war, but at the cost of a world that is less safe, less secure and less amenable to the supposed ideals of the United States of America.

* * *

The wars in Iraq and Afghanistan were driven, in addition to the lure of black gold, by the dual ideological impulses of the Bush administration: a muscular neoconservative belief in the power and right of the US military to shape the world; and a near-religious faith in the efficiency and productive power of the unfettered free market, both fervently held and actively promoted, for its own benefit, by the US defence industry.

These two strands were woven together in 1997 with the publication of the PNAC’s Statement of Principles, which lamented the certainties of the Reagan years and argued for the need ‘to accept responsibility for America’s unique role in preserving and extending an international order friendly to our security, our prosperity, and our principles’.32 And, consequently, the ‘need to increase defense spending significantly if we are to carry out our global responsibilities today and modernize our armed forces in the future’.33

The signatories of the Statement were many of those who would lead the path to the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan: Jeb Bush, the brother of George W. Bush, Dick Cheney, Donald Rumsfeld, Paul Wolfowitz, ‘Scooter’ Libby and Zalmay Khalilzad, the US ambassador to both Afghanistan and Iraq in the years following the US invasion.

Three years later, the hubristic logic of this neoconservative call to arms would become the guiding light for the new rulers in the White House. In September 2000, the PNAC published the defining report, Rebuilding America’s Defenses (see Chapter 14). Coming as it did only months prior to the 2000 US election, it had a significant impact on George W.’s defence policy. It warned that states were deterred from threatening American supremacy and the values it holds dear by the capability and global presence of American military power. But it warned that if that power declined, ‘the happy conditions that follow from it will be inevitably undermined’.34 The upshot was a clarion call for a massive increase in defence spending.

The 2000 report did not specify exactly who was the largest threat to American security. But it was clear that Iraq was in the crosshairs. On 26 January 1998, the PNAC sent an ‘open letter’ to Bill Clinton, signed by many who had signed the Statement of Principles. The open letter highlighted Saddam Hussein’s alleged nuclear and biological weapons programmes – that had once been helped along by the US but totally destroyed after the 1990 Kuwait debacle – and pushed hard for a policy of regime change. It was, in other words, a dry run for the future war in Iraq.35

At the same time as the future Bush administration was outlining its foreign policy principles and badgering for an invasion of Iraq, most of those who signed the Statement were making fortunes in business, as we’ve seen. Dick Cheney was CEO of Halliburton while Donald Rumsfeld was amassing an estimated $12m from his forays into the private sector.36 They were the standard-bearers of both the politician-entrepreneur and the emerging disaster capitalism industry.

Unsurprisingly, when America finally went to war, it would be done with the firm belief that subcontracting out its functions to the private sector was not only efficient and rational, but the essence of patriotism.

The attacks on the World Trade Center and the inauguration of the War on Terror galvanized George W. Bush’s presidency and provided fertile ground for the new militarism that Cheney and Rumsfeld had spent years evolving. Within a month of the tragedy the US was attacking Afghanistan, hoping to dislodge the Taliban government whose predecessors it had once so aggressively championed with Charlie Wilson at the forefront. Faced with the might of the American military, the Taliban melted into the hills from where they would fight an ongoing low-intensity guerrilla war for much of the next decade. At the time, however, what impressed many in the US was the ease with which the Taliban were swept aside. American military might seemed unassailable and the prospects for future campaigns seemed certain. The time had come to fulfil the neocons’ dream of kicking Saddam out of power.

On 20 March 2003, the US, accompanied by small contingents from the absurdly named ‘Coalition of the Willing’, invaded Iraq. In just under fifty days the US military marched through the country and seized the capital, Baghdad. Saddam Hussein, later captured in a muddy hole near his home town armed only with a solitary pistol, was whisked away to face trial and execution. On 1 May 2003, in a photo-op that would come to define his faintly ridiculous presidency, Bush Jr addressed a global television audience aboard the USS Lincoln. ‘Major combat operations in Iraq have ended. In the battle of Iraq, the United States and our allies have prevailed.’37 In reality, the war had just begun.

* * *

The ease of the US’s apparently quick victories in Afghanistan and Iraq suggested that it had run a tightly controlled and efficient military campaign. In reality, while the first ‘surges’ into the respective countries were carried out with remarkable force, only the most basic planning had been undertaken as to how the countries would be run in the aftermath of the military successes. It soon became clear that the Coalition Forces would have to prepare to dig in for the long haul. Without clear plans in place, those in control of Iraq had to fumble for solutions, moving from one crisis to another. The US administration in the country became an ‘adhocracy’,38 with short-term solutions used to quell a thousand different fires without the requisite thinking through of all the consequences. With a small invasion force the Coalition Provisional Authority (CPA) and those that followed were forced to turn repeatedly to the private sector to fill in the gaps, ballooning the costs of the war while ensuring a massive flow of income to those lucky enough to be on the inside track – a state of affairs that delighted Cheney, Rumsfeld and their acolytes, who had aggressively punted the privatization of conflict.

Far more than had been anticipated or fantasized about by the dogmatic privatizers, the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan would be contractor wars. They are easily the largest privatized conflicts the world has ever seen. Contractors have been used in previous wars undertaken by the US but never on this scale. During the First World War for example, the US deployed 1 contractor for every 20 soldiers, 1 for every 7 in the Second World War and 1 for every 6 in Vietnam.39 As of March 2010, there were 207,553 contractor personnel active in Iraq and Afghanistan compared to 175,000 troops – a ratio of 1.18 contractors per soldier in the region. Afghanistan was even more heavily dependent on contractors: 112,000 contractors supported 79,000 troops, a ratio of 1.42 contractors to every soldier.40 Remarkably, a full 11,610 contractors were employed in Iraq as of March 2010 to supply security – a tacit admission that the US Army could not control the country without relying on a sizeable mercenary force.41

While estimating the total amount awarded to contractors in Iraq and Afghanistan is difficult, some figures are indicative. Between 2003 and 2007, US agencies had placed over $85bn in contracts with private suppliers in Iraq.42 Other figures suggest that the values of contracts have increased exponentially since then. In one study the GAO reported that during the fiscal year 2008 and the first half of 2009, $39bn had been awarded via 84,719 contracts in the two countries: over $2bn per month or $26bn a year.43 Taken together, this would suggest that contractors had earned considerably more in Iraq and Afghanistan than the $100bn by 2010 that has previously been estimated.

Easily the largest contract was awarded to KBR, the engineering and logistics subsidiary of the Texas-based Halliburton, until June 2007, when it was sold. By March 2010, KBR had earned $31.4bn via its hugely controversial LOGCAP, which Dick Cheney had been instrumental in developing and awarding.44 This figure excludes the largest contract placed by the US Army Corps of Engineers in Iraq, a $7bn deal with KBR to reconstruct Iraqi oilfields damaged in the conflict. In return for this brazen cronyism, Halliburton/KBR made hay out of the cost-plus contracts as they mismanaged projects, inflated prices, overspent and double-billed the government they were serving.45

After Cheney left the Defense Department in 1992, his appointment as CEO of Halliburton in 1995 led to a remarkable improvement in the company’s fortunes, especially with regard to federal contracts. In the five years prior to his arrival, Halliburton had received a paltry $100m in government credit guarantees. Under Cheney’s five-year leadership, Halliburton received fifteen times that amount – $1.5bn.46 Cheney was paid well for his services: for fifty-eight months he received $45m.47 As we’ve noted, some of these payments were made to him while he was Vice President.48 Charles ‘Chuck’ Lewis, the Executive Director of the Center for Public Integrity, was vituperative:

This is not about the revolving door, people going in and out. There’s no door. There’s no wall. I can’t tell where one stops and the other starts. They’re retired generals. They have classified clearances, they go to classified meetings and they’re with companies getting billions of dollars in classified contracts. And their disclosures about their activities are classified. Well, isn’t that what they did when they were inside the government? What’s the difference, except they’re in the private sector?49

Further muddying the waters was the fact that Halliburton was one of the largest contributors to the Republican election campaign that propelled George W. Bush to the presidency. Between 1998 and 2003, the company donated $1,146,248 to the Republican Party. The Democrats, in the same period, received a comparatively risible $55,600 from Halliburton’s lobby fund.50

The first major scandal erupted only months after the Iraq War began in earnest.51 As the years went on it became clear that KBR’s mismanagement and misconduct was systemic, omnipresent and, perhaps most importantly, seemingly hardwired into the corporate culture of the company. It reflected the contradiction at the heart of the hawks’ privatizing zeal: support for free markets and private enterprise were portrayed as the essence of patriotism, but players in these markets act only on the basis of maximizing bottom-line profit and not out of any idealistic vision of patriotic duty.

This was certainly the impression gained by David Wilson, a fifty-year-old Vietnam veteran who went to work for KBR. He was shocked at his corporate induction by an extraordinary pep talk in which the recruits were told they were going to Iraq ‘for the money’. The trainer told them they were not going to help the troops, not going to help the Iraqi people, not going for America, but ‘FOR THE MONEY’, a slogan they had to chant repeatedly. And once in Iraq his worst suspicions were confirmed as mismanagement, ineptitude and wastage eventually cost the lives of six KBR drivers and two soldiers.52

KBR could only get away with this behaviour because they were allowed to. The US Army and government could barely keep tabs on what the contractors were doing. In 2009, the bipartisan Commission on Wartime Contracting – established as a means to prevent future contractor debacles – published an interim report indicating that, while the US was happy to pour hundreds of billions of dollars into the hands of contractors and the military, it was far more stingy when it came to employing people to monitor or regulate these activities. One staff member was responsible for overseeing nineteen contracts, over and above his normal military duty.53 Similarly worrying was the fact that the Defense Contract Audit Agency (DCAA), responsible for monitoring and auditing contracts placed by the DOD, has run for much of the Afghanistan and Iraq wars without sufficient staffing, with numbers remaining the same while contracts increased by 328 per cent.54

When the DCAA reviewed the various contracts awarded during the War on Terror it found literally billions of dollars had been frittered away on wasteful and excessive spending. In total by the end of the 2008 fiscal year, the DCAA had recommended reductions in billed costs of $7bn – over and above a further $6.1bn where ‘the contractor had not provided sufficient rationale for the estimate’.55 A partial audit of KBR’s LOGCAP contract found $3.2bn in dodgy expenditure and an additional $1.5bn that the contractor could not support.56

Even more galling was that, in many instances, contractors hired by the US in Iraq and Afghanistan didn’t do a particularly good job, critically undermining the US missions in each country.57

* * *

Of course, this is not to suggest that only KBR and Halliburton could be criticized for undermining the reconstruction of Iraq. Equally damaging to US legitimacy in the broader region was the role of private security contractors, or, to use a more loaded but accurate term, ‘mercenaries’. Just as advertising was once characterized as ‘the pimple on the arse of capitalism’, so mercenaries could be appropriately described as the vultures circling the Grim Reapers of the arms trade. Given the nature of their activities it is unsurprising that they sometimes get involved directly and indirectly in the arms trade itself.

The invasion of Iraq unleashed boom years for mercenaries around the world.58 Contractors were needed to fill the gaps caused by the US force in the country being smaller than needed. They were employed en masse to protect bases, embassies and, bizarrely, local and foreign dignitaries. Indeed, the first US proconsul in Iraq, Paul Bremner III, was protected by a crack team of hired guns from perhaps the most controversial security company of all, Blackwater.

Equally important in boosting the numbers of contractor security staff was the fact that the US military had proved unable to protect the other private contractors, forcing them to hire mercenary outfits to protect themselves. Soon, the cost of hiring private security was swallowing at least 10 per cent, and perhaps up to 25 per cent, of many reconstruction budgets.59

In addition, mercenaries were so involved in fighting the war itself that by September 2010 contractor deaths in Iraq and Afghanistan constituted more than 25 per cent of all fatalities afflicting the US and its allies.60 In Blood Money, his study of waste, greed and lost lives in Iraq, T. Christian Miller notes that ‘contractors, for the first time in US military history, were not only supporting the war, they were in the middle of it, fighting and dying alongside soldiers’.61

Unfortunately, with mercenary services came chequered pasts and questionable motives. The type of hired guns employed by private security contractors at salaries as high as $200,000 a year soon raised eyebrows. They included South Africans drawn from the country’s notoriously vicious apartheid-era security forces62 and Serbian ex-special force operatives, many of whom were alleged war criminals who had honed their skills during the genocidal Balkans conflict.63 A British company by the name of Aegis was awarded a security contract worth just under $300m in 2004.64 The company was headed by Colonel Tim Spicer, a controversial former British Army officer who also ran Sandline International, a mercenary group that was involved in numerous contentious conflicts and arms trading. In 1998, Sandline had been hired by Sierra Leone’s President Ahmed Kabbah to help restore him to power following a coup. Sandline imported 35 tons of Bulgarian AK-47s despite Sierra Leone being under an arms embargo at the time.65 Spicer was to claim that he had imported the weapons with the approval of the British Foreign Office, a view later upheld by a number of government inquiries.66 According to an investigation by the UK House of Commons Committee on Foreign Relations, Spicer’s cargo had been given a ‘degree of support’ by Peter Penfold, the UK’s High Commissioner to Sierra Leone. Penfold ridiculously claimed that the shipment did not violate the terms of the arms embargo. The diplomat was released from his position and placed in a different department.67 Once Spicer’s background became public, Democrats in the US wrote to Donald Rumsfeld asking him to cancel Aegis’s contract in favour of a less controversial candidate. Rumsfeld and the DOD rejected the request.68

Given that mercenaries are generally viewed with suspicion, one would have expected that they would be subject to intense oversight. The exact opposite is true. On 27 June 2004, in one of his last acts as proconsul, Paul Bremner decreed Order 17 into law,69 under the terms of which all staff associated with the Allied forces and the contractors they hired were exempt from Iraqi law.70 Order 17 would remain in effect until explicitly struck down by the Iraqi government. This placed contractors such as Aegis and Blackwater in a legal lacuna, especially as they did not operate under the terms of the Uniform Code of Military Justice that governed the behaviour of all US troops71 and it also wasn’t clear that US courts would have jurisdiction over crimes committed by contractors on foreign soil. They had been given a de facto ‘licence to kill’.72

The author of Order 17 was one Lawrence Peter, who at the time was in charge of overseeing the activities of Iraq’s Ministry of the Interior.73 Soon after the controversial Order was passed and the CPA ceased to exist as power was handed over to the newly elected government, Peter found employment elsewhere: as a lobbyist and liaison for the Private Security Company Association of Iraq. ‘The new Iraq,’ noted the respected journalist Sidney Blumenthal, ‘included a revolving door.’74

Blackwater, among others, thrived in this lawless environment. Formed in 1996, the company was led by a former Navy Seal, Erik Prince, a man with impeccable Republican connections.75 As Blackwater grew following the September 11 attacks, it was assiduous in adding well-connected individuals to its board, such as J. Cofer Black, appointed vice-chairman after a twenty-eight-year career in the CIA, latterly as head of the CIA Counter-Terrorist Center, from where the policy of extraordinary rendition emerged.76 Another influential appointee was the COO, Joseph Schmitz, who joined the company in September 2005. A month previously Schmitz had resigned as the Defense Department’s Inspector General overseeing all contracts placed by the Pentagon, after allegations that he had inappropriately intervened, or allowed political intervention, in suspiciously awarded contracts, including the Boeing tanker refueller debacle and millions that were directed the way of Blackwater.77 Incredibly, in September 2010 Schmitz was awarded a sole-source contract to independently monitor the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction’s (SIGAR) efforts to alleviate deficiencies in its investigative division.78

With such connections, perhaps Blackwater’s growth is understandable. Prior to 9/11, the company had a $1m federal contract; by 2009 it had received roughly $1.5bn from the Pentagon to supply mercenary services in Iraq and Afghanistan, as well as other conflict zones.79 The company’s name became synonymous with the use of excessive force after it was embroiled in the unjustified killing of at least eighteen Iraqi civilians in two separate incidents in Iraq.80

Shortly after Blackwater was banned from operating in Iraq for its involvement in the shooting of innocent civilians in Baghdad, it was reconstituted as Xe Services and was still bidding for US government contracts to operate in areas besides Iraq, including Afghanistan. It was discovered that Xe had committed 289 violations of the Arms Export Control Act, for which it faced possible prosecution.81 Fortunately for Blackwater/Xe, it escaped with a mere slap on the wrist: a civil fine of $42m paid as part of a settlement agreement with the State Department in August 2010. This was considerably less than the maximum $288m fine that could have been levied.82 By avoiding court, Xe would remain eligible to receive further government contracts.83 Business as usual then for the contractor whose legacy to Iraq’s struggling democracy is mayhem, murder, massive wastage and an undermining of whatever rule of law may exist.

Despite mounds of evidence pointing to mass illegality, misconduct and corruption, no contractors employed in Iraq have faced the threat of debarment. In fact, KBR could earn $50bn over ten years from a slightly amended LOGCAP IV alone.84

* * *

The boom years for private contractors that followed 9/11 were as good for the conventional defence industry: weapons manufacturers, dealers and brokers. While the activities of the likes of KBR and Blackwater have dominated news cycles and analysis, little attention has been paid to the super-profits earned by the formal defence trade or the shadow world, some of whom emerged from the network of brokers, dealers, thugs, money launderers and gangsters linked to Merex.

While uncertainties and difficulties exist in estimating exactly how much the US military has spent on defence procurement specifically related to the Iraq and Afghanistan wars, what is clear is that it is an extremely large amount. By far the largest procurement costs directly linked to the wars in the Middle East are those associated with the practice of ‘reset’, the policy whereby the US military continually repairs, upgrades or simply replaces military equipment that has been used on the field of combat. This ‘resets’ the equipment and units that use them to their operational level as it existed prior to the conflicts. It has been a massive and ongoing programme, especially since 2005. As of 2006, it was reported by the Congressional Budget Office that roughly 20 per cent of the entire inventory of the US military had been deployed in Iraq, Afghanistan and surrounding areas.85 The Army alone had $30bn worth of equipment stationed in the two theatres by early 2007.86

The harsh conditions have meant a high rate of attrition, repair and replacement. As a result the US Army has estimated that a considerable amount of the weapons deployed in Iraq and Afghanistan would need to be replaced every year to keep stocks at pre-war levels – not repaired, but actually replaced. It has been estimated that 6 per cent of the total helicopter force deployed would have to be replaced annually; roughly 5 per cent of fighting vehicles, and 7 per cent of trucks.87 If equipment levels remained the same, by 2020 every helicopter deployed in Iraq and Afghanistan would be due for replacement. Whether forces will remain in the country until 2020 is unsure, especially as President Obama announced, in mid-June 2011, a newly revised timeline for withdrawal from Afghanistan and Iraq that should see the bulk of forces moved out by 2014.88 This, in turn, has been muddied by reports of a ‘secret pact’ between the US and Afghan governments, committing thousands of trainers, contractors and secret forces agents to the country until 2024.89 Nevertheless, if the conflict rumbles on – which the 2010 budget cautioned, with temporary plans until 2020 – a full 20 per cent of the entire military might of the US would be replaced, a mouth-watering prospect for the MICC.

When repairs to vehicles and equipment are included it becomes a truly gargantuan undertaking, which would see thousands of pieces of equipment sent to the mechanics of large defence contractors. The CBO has reported that after two years of operations in Iraq, it was necessary for every Abrams tank and Bradley Fighting Vehicle that returned home to be sent for repairs. Repairing each Bradley costs $500,000, each Abrams tank $800,000.90 The total annual cost for simply cleaning sand and dust from the Bradley vehicles and Abrams tanks is between $700m and $1.2bn.91

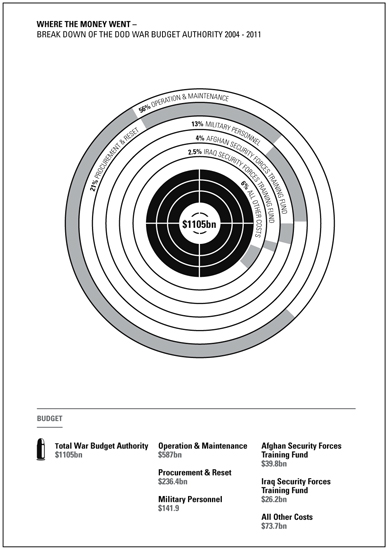

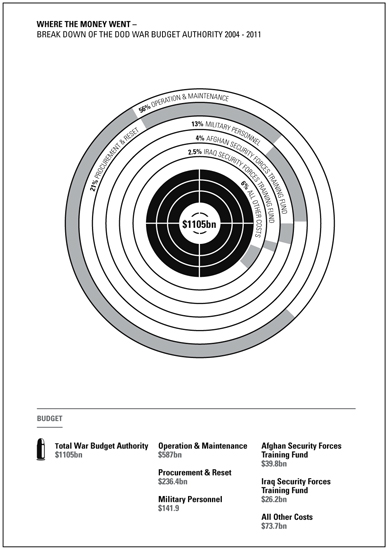

As one would expect looking at these figures, the costs related to procurement and reset in Afghanistan and Iraq have skyrocketed. In 2004, the total amount set aside for procurement in the supplemental budgets that funded the wars was $7.2bn. In 2008, at its peak, a massive $61.5bn was set aside. For the six years between 2004 and 2010, $215bn had been budgeted, with a further $21.4bn requested for 2011.92

From 2004 onwards, the cost of war in Iraq grew steadily. That year, it cost roughly $4.4bn a month; in 2006, $7.2bn a month; and, in a sudden leap, $10.2bn and $11.1bn a month in 2007 and 2008 respectively.93 The leaps between 2006 and 2007–8 – about a 40 per cent increase in the cost – occurred at a time when troop levels remained stagnant. Almost the entire increase in the cost of war was thus due to reset-related procurement that began in earnest in 2007.94 To reiterate: once resetting and replacing equipment really started, it increased the total cost of war in Iraq by at least 40 per cent. Once troop drawdown in Iraq is finally completed, the reset of equipment in the field as of 2010 is estimated to cost at least $40bn and take roughly two years to complete – over and above the annual reset requirements described above.95 As a result, of all the factors that have contributed to the ‘spiralling’ costs of war, reset has been ‘perhaps … the most significant’, according to the Nobel laureate Joseph Stiglitz and Dr Linda Bilmes of the Kennedy School of Government.96

The amounts described were incurred over and above the existing DOD budget, which mushroomed during the War on Terror, under George W. Bush and for at least the first two fiscal years of the Obama administration.

In 2007, the CBO conducted a study of reset costs incurred in Iraq and Afghanistan. It discovered that more than 40 per cent of the costs requested for reset in the two wars was actually being spent on either upgrading existing systems, rather than resetting them to pre-war levels of operation, or, crucially, ‘buying new equipment to eliminate shortfalls in the Army’s inventories, some of which were long-standing’.97 So, far from merely retaining operating levels, the DOD undertook massive expenditure that would improve the stock of the entire military and paid for it out of the budget for the Iraq War. In 2006, for example, under the rubric of ‘reset’, it was decided to replace the entire Pentagon fleet of 18,000 Humvees with vehicles better able to resist improvised explosive devices (IEDs).98

In another instance, the Pentagon inserted a request for two Joint Strike Fighter jets from Lockheed Martin into the 2007 requisition for funds for the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan – even though the fighters would never be ready in time to see action in either conflict.99 By restocking inventories on the war tab, the Army was able to fund purchases that it was not able to undertake within the already huge amounts dedicated to the military in the DOD budget. Even the budgets for the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan have been padded with pork barrel projects: ‘It’s a feeding frenzy,’ an Army official involved in budgeting complained: ‘Using the supplemental budget, we’re now buying the military we wish we had.’100

Figure 7: US Department of Defense budget and spending on the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan

What makes this even more concerning is that, by being included in the supplemental budgets for the wars, these pork barrel projects could effectively pass under the radar, without any accountability. This is a function of the absurd budgeting process for the wars in the Middle East. Supplemental budgets are passed by Congress – emergency budgets that appropriate money for needs outside the usual budgetary process. These budgets are passed fast and hard, the exigencies of war demanding that many line items be taken on faith: in one instance, a $33bn request under the Iraq Supplemental included a meagre five pages justifying the expenditure.101 ‘In my opinion as a budgeting professor,’ Dr Linda Bilmes commented: ‘this is not the best way for the US budget system – or any budget system – to operate. The purpose of the emergency supplemental facility is to fund a genuine emergency.… The late transmittal of supplementals during the budget process leads to less congressional review and lower standards of detailed budget justification than regular appropriations.’102 The GAO concurred: ‘The use of emergency funding requests and budget amendments for ongoing operations of some duration reduces transparency, impedes the necessary examination of investment priorities, inhibits informed debate about priorities and trade-offs and, in the end, reduces credibility.’103

Each of the major defence contractors was well placed to provide the weapons used in the wars. As detailed above, Lockheed Martin offered a massive range of products suited to the War on Terror. These included Multiple-Launch Rocket Systems used to launch cluster bombs against Iraqi opponents, leaving behind deadly fragments of unexploded bomblets that killed or injured both Iraqis and US soldiers.104 Its F-16 jets were heavily involved in the initial bombings, and its Hellfire air-to-ground missiles were used extensively to attack Iraqi armoured vehicles.105 The company’s communication equipment was also widely used and replaced on a regular basis.106

Lockheed had also made the prescient and lucrative move into supplying privatized services to the military. The company had become, as a result, a vertically integrated war industry of its own accord. ‘Lockheed Martin is now positioned to profit from every level of the War on Terror from targeting to intervention, and from occupation to interrogation,’ Bill Hartung commented in 2005.107After Lockheed purchased Sytex in March 2005, and acquired a portion of Affiliated Computer Services (ACS), it supplied interrogators and analysts for use by the DOD. Some of the interrogators were deployed to Abu Ghraib, others involved at Guantanamo Bay. Lockheed was well positioned to receive a sizeable chunk of the ‘Intelligence Industrial Complex’ market, which received $50bn from US intelligence agencies every year – nearly three quarters of which was spent on private contractors.108 The company was the largest private intelligence contractor employed by the US government, making it jointly ‘the largest defence contractor and private intelligence force in the world’.109 After KBR, Lockheed Martin was the second-largest contractor to the US in Iraq and Afghanistan.

BAE, meanwhile, provided almost all of the US’s Bradley Fighting Vehicles, for which it received a new $2.3bn contract in 2007.110 After BAE acquired Armor Holdings for $4.532bn in 2007, it was also in line for contracts related to the Pentagon’s plan to replace its 18,000 Humvees with mine-resistant vehicles in which Armor specialized.111 Northrop Grumman’s products were also in high demand, in particular its B-2 strike bomber that was used continuously to effect ‘shock and awe’.

It has also taken the lead, along with Israel’s Elbit Systems, in building unmanned aerial vehicles and militarized drones – the unmanned aircraft that controversially fly the deserts and mountains of Iraq, Afghanistan and Pakistan searching for, and eliminating, insurgents and terrorists.112

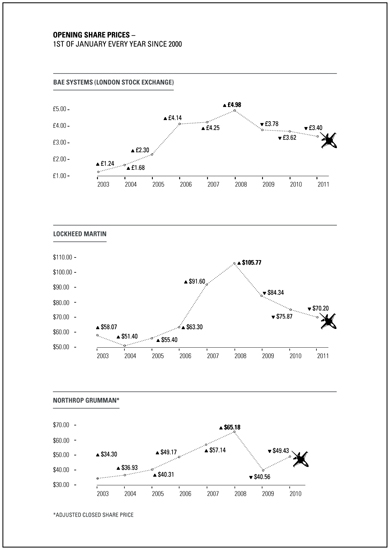

The startlingly roughshod manner in which budgets were passed has made it almost impossible to track the exact amounts flowing from the war budgets and those of the intelligence services into the coffers of the formal defence industry. There is little doubt that the years since 9/11 have been extraordinarily lucrative. Some indication is given by the explosion in share prices of the largest defence contractors. In January 2003, for example, the monthly average price for a BAE share on the London Stock Exchange was £1.13. Its September 2010 monthly average was £3.41. Similarly, Lockheed Martin’s share price in January 2000 was $15.32. As of September 2010, the monthly average price for a Lockheed share was $71.28. So too Northrop Grumman – its share grew from $19.76 to $60.63 over the same period.113 Both BAE and Northrop Grumman reported share price increases of over 300 per cent, while Lockheed Martin’s was a virtually unheard of 465 per cent increase since the inauguration of the War on Terror.114

Figure 8: Share price movement in BAE, Lockheed Martin and Northrop Grumman

The largest ‘reset’ costs budgeted during the Middle East wars were inserted in the years 2007 and 2008 – with over $60bn budgeted in the latter year.115 Almost without exception, the share price of the major defence companies reached a decade-long peak in this same period. BAE’s shares, for example, rocketed above £4 a share in December 2006 and remained there until October 2008. Its historical peak was in December 2007, where it reached £4.98 a share, or a full 440 per cent increase on its January 2003 price.116 Lockheed Martin’s shares also bulged, soaring from $65 in May 2006 to a decade-high of $109 in August 2008.117 Both BAE and Lockheed’s shares dropped substantially in October 2008 and fell consistently thereafter – a month before Barack Obama took control of the White House promising a withdrawal from Iraq and, most importantly, the procurement costs in the supplemental budget were slashed from $61.5bn in 2008 to $32bn in 2009.118

* * *

The lack of oversight and control over defence spending – and the haste with which major projects were undertaken – meant that Iraq and Afghanistan also turned into extremely lucrative markets for arms dealers and brokers. Indeed, some of the earliest operations in Iraq opened the floodgates for the one man most closely associated with questionable practices: Viktor Bout.

In 2003, shortly after the invasion of Iraq, the US military faced a major problem. While it had successfully taken control of a number of key landing strips, conditions remained perilous for civilian contractors. Baghdad International Airport, for example, was subject to repeated mortar fire from the surrounding suburbs, almost universally off-target, and planes flying over Baghdad’s suburbs often had to dodge anti-aircraft fire. As a result, US civilian cargo operators were advised against running supplies into the country. This left a major hole, as cargo planes were desperately needed to help the US undertake the largest air cargo operation since the Berlin Airlift.119

To fill the gap, the US and its contractors turned to a range of air cargo suppliers operating around the world. From 2003 until at least the end of 2005, one of the most consistent operators was Irbis Air – an airline owned and controlled by Viktor Bout. In 2003–4 alone, Irbis Air conducted hundreds of runs to Baghdad and other high-security airports, carrying items ranging from tents and boots to military hardware and ammunition. Irbis landed in Baghdad ninety-two times from January to May 2004, while also conducting deliveries to other Iraqi airports. Between March and August 2004, the Defense Logistics Agency confirmed that Irbis Air had refuelled 142 times in Baghdad alone.120 The income Bout earned from his flights in Iraq was not inconsiderable. At $60,000 per return run, he was estimated to have earned $60m between 2003 and 2005 – over and above the free fuel regular cargo operators were given by the US military.121

Bout’s client list in Iraq made for intriguing and damning reading, given his status as ‘the merchant of death’:

[US military] officials explained that Irbis had been hired repeatedly as a secondary military subcontractor, delivering tents, frozen food and other essentials for American firms working for the US Army and US Marines. The Bout flagship also was a third-tier contractor for the US Air Mobility Command, flying deliveries for Federal Express under an arrangement with Falcon Express Cargo Airlines, a Dubai-based freight forwarder. And Irbis was also flying … under reconstruction contracts with the petrochemical giant Fluor, and with Kellogg Brown and Root.122

For Chris Walker, the man in charge of Baghdad airport’s civilian cargo control, Bout’s involvement was an embarrassment, and a blindside, as he had assumed that all airlines that operated in the months after the invasion had been properly vetted. As it turned out, the CIA had flagged Bout’s operations – but the email failed to reach the appropriate person at the CPA offices.123 Walker was caught in a real bind: even though Bout was likely to be placed on the Asset Freeze list and was wanted by both the FBI and the CIA, stopping his flights would have fatally disrupted stretched supply lines. As a result, as of mid-2005 Bout’s planes were still flying into Iraq. When it was confirmed that the US Treasury was placing Bout and his airlines on an Asset Freeze list and the Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) list that outlawed the use of certain contractors, the US military’s Central Command asked for a week’s reprieve. It was granted, allowing Bout to deliver a final shipment of arms, ammunition and other supplies. ‘It ensured that private contractors continued paying Bout’s network despite the fact that any other American firm doing the same would have been subject to prosecution.’124

While the Russian was able to make a fortune from his contracts directly with the US, the wars provided other opportunities for arms dealers. One of the most pressing needs was to restock the military supplies of the Iraqi security forces, which had largely faded into the shadows during the initial invasion. Re-equipping the de-Baath’d forces was crucial as the Coalition Forces hoped that Iraqis would assist in fighting the insurgency and retaining law and order. Millions of tons of small arms and ammunition flooded into the two countries, and Iraq in particular. Between 2003 and 2007, roughly 115 orders were placed for arms deliveries to the Iraqi security forces at a total cost of $217m.125 As of July 2007, the US training command confirmed that 701,000 weapons had been imported for Iraq’s security forces.126 Most of these were ‘Soviet-type infantry weapons’, including AK-47s, portable machine guns, RPGs and pistols. Unfortunately, these deals were often undertaken with the help of brokers with dubious track records – and may, in fact, have ended up supplying weapons to the very people the Coalition Forces were fighting.127

One of the most consistently used primary contractors has been Taos Industries, currently a subsidiary of Agility and Defense Services128 and a recent joint recipient, with Dyncorp and one other company, of a $643.5m one-year task order under LOGCAP IV.129 Taos specializes in ‘the procurement of non-standard matériel, including equipment for security forces, foreign military systems and hard-to-find components’.130 In one deal, the company was contracted by the US to deliver 99,000 kilograms of AK-47 rifles to the Iraqi security forces.131 The weapons were to be sourced from Bosnia, where a considerable stockpile of surplus weapons remained following the Balkans wars of the mid-1990s. To fulfil the order Taos employed a cargo company by the name of Aerocom.132

As of 2004, Aerocom did not have a valid air operator licence after it had been involved in a particularly dodgy deal only a year previously. In 2003, the UN reported that Aerocom had been involved in supplying Charles Taylor with tons of small arms and ammunition. According to the report, the company had been hired by Temex Industries to effect the delivery of weapons from Serbia to Monrovia in violation of the UN arms embargo still in force against the country.133 Aerocom also had connections to Viktor Bout. Records showed that Aerocom and Jet Line – a part of Viktor Bout’s delivery empire134 – had frequently leased each other’s jets or used each other’s licences to conduct deliveries.135

Another Taos acquisition brought attention to the fact that a substantial number of arms bought for the Iraqi security services may have been diverted to the insurgents fighting against the US. In 2004, Taos was asked by the US to arrange a separate consignment of weapons for the Iraqis. It in turn contracted a London-based outfit by the name of Super Vision International,136 which decided to source the arms from Italy, acquiring 20,318 Beretta 92S handguns from the Beretta company itself.137 The consignment was shipped to Exeter, from where it was delivered to Baghdad. Italian police, however, were not happy with the deal when they discovered that Beretta had sold the weapons without the appropriate licence. The weapons were old and sourced from the Italian interior ministry before being refurbished and sold on to the UK. But Beretta did not have the appropriate registration to sell refurbished arms. The company had also listed the guns as ‘civilian’ products in their export papers, even though the 92S had been declared a ‘weapon of war’ by the Italian legal system. Registering the handguns as civilian made the deal subject to far fewer checks than if they had been registered as military matériel.138

Although the weapons were delivered to Baghdad in July 2004, they were only officially accepted in Iraq on 18 April 2005.139 It is uncertain why the delay occurred. However, the CIA informed the Italian police in February 2005 that Al Qaeda operatives who had been captured in Iraq were in possession of Beretta 92S weapons – allegedly from the very same batch that Beretta had exported to Exeter on behalf of Super Vision and Taos Industries.140 The captured insurgents were fighting on behalf of Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, Al Qaeda’s principal leader in Iraq. It is not entirely clear how the weapons were passed on to Al Qaeda, although it had long been rumoured that Iraq’s police had been infiltrated by insurgent elements. The Italian police service acted quickly and seized the thousands of Berettas still in Italian warehouses awaiting shipment to the UK.141

The Beretta deal illustrated that systems to ensure weapons bought by the US for the Iraqi military didn’t fall into insurgent hands were inadequate if they existed at all. In July 2007, the GAO published a report that didn’t generate much interest, despite its explosive content. Auditors and investigators from the GAO travelled to view in situ how the handover of weapons had been managed in Iraq, and how the US had kept track of the weapons it had bought for the security services. It found that until December 2005 the body responsible for training and arming the Iraqis ‘did not maintain a centralized record of all equipment distributed to Iraqi security forces’ and that, as a result, the same body had ‘not consistently collected supporting documents that confirm the dates the equipment was received, the quantities of equipment delivered, or the Iraqi units receiving the equipment’.142

A mountain of weapons was missing. By September 2005, the Iraqi security forces had received 185,000 AK-47 rifles, 170,000 pistols, 215,000 items of body armour and 140,000 helmets. The US entity responsible for their distribution could not account for 110,000 AK-47 rifles, 80,000 pistols, 135,000 items of body armour and 115,000 helmets143 – more than 50 per cent of all the equipment that had been delivered at great cost. Not being able to account for the weapons did not necessarily mean that all of them had found their way to the black market – some were probably just ‘lost in the system’. But, as David Isenberg, US Navy veteran and senior analyst with the British American Security Information Council, commented after the 2007 GAO report was published: ‘it seems fairly likely that some of the missing weapons are being used against US forces in Iraq. Given that the most readily accessible black market for those stolen weapons is in Iraq, some of those are going to be bought by the insurgents.’144

Considering the size of the weapons procurement for the Iraqi forces – and the quantity of logistics and reconstruction contracts – it is not surprising that dealers tied into the Merex network have operated in Iraq. Merex and the Mertins family have been at the rock face of the weapons industry during America’s two great wars of the last five decades: the Cold War and the War on Terror. Joe der Hovsepian has been there with them.

Despite his involvement with a menagerie of unsavoury arms dealers and his participation in a number of illegal weapons transactions throughout his career, der Hovsepian profits from American largesse in Iraq and Afghanistan. Having described the Americans as ‘the biggest terrorists on the planet’ at the outset of our conversation, he wore an ironic grin as he showed me his US Department of Defense ID and a USAID identity document enabling him to operate as a contractor in Iraq. He also showed me a letter from USAID dated 6 April 2005, confirming his appointment as a security consultant in Iraq. While der Hovsepian said both had expired, the USAID ID seemed to be valid until 2011. Both the Department of Defense and USAID were unwilling to confirm the name of consultants they use in conflict zones.

He worked for KBR in Iraq, as ‘they always get contracts to do all the work. They even sign up for projects that don’t exist.’ He is a security adviser for four other companies in the country: Najran Co. Ltd; Dahab Al E’amar Co. Ltd; Jawhart Al-Eman Co. Ltd; and Jawharat Al Mahabba Co. Ltd.

He explained how he gets equipment into Iraq without it being captured by insurgents. He will have a truck of one colour take goods and matériel up to the border post. Then, because there are informants at the borders, he surreptitiously changes vehicles on the other side, so the insurgents waiting to ambush are looking for a different colour truck. He also spends a lot of time meeting tribal leaders, wearing traditional dress. He does this to reduce the possibility of raids on his vehicles and sometimes buys their protection.

During my interview with der Hovsepian, he was adamant that Helmut Mertins, the son of Merex’s founder, Gerhard, was operating in Iraq. Der Hovsepian invited me to check for myself and gave me an email and physical address for Helmut. While Mertins was unwilling to see me, the address itself made for interesting reading. The email address der Hovsepian had on file suggests that Mertins was working for a company called Sweet Analysis Services Inc. (SASI). SASI is headquartered in Alexandria, Virginia – the current home of Helmut and the town from which the US branch of Merex operated.

SASI is named after its founder, Patrick Sweet, a self-proclaimed US Army veteran. The company, founded in 1990, currently has additional offices in Kiev in the Ukraine and Bucharest in Romania. Sweet has made some powerful friends in the Ukraine. A press release from 2009 confirmed that he served on the board of the US–Ukraine Business Council.145 According to its corporate website, SASI runs a dedicated department handling ‘Foreign Material Acquisition and Foreign Military Sales’.146 The list of weapons SASI procures for clients is impressive, including thermobaric munitions, rocket-propelled grenades, anti-ship cruise missiles, tanks, infantry weapons, small- and large-calibre ammunition, radar systems and unmanned aerial vehicles.147

Patrick Sweet previously worked for Vector Microwave Research Corp., which performed secret tasks for the CIA and the US military, ‘using guile, experience and connections, including those of its president, retired Lt. Gen. Leonard Perroots, a former director of the Defense Intelligence Agency’.148 Vector was contracted to acquire foreign missiles, radar and other equipment for US intelligence agencies. So complex was the web of connections surrounding the company, that its founder, Donald Mayes, became a business partner with China’s state-owned missile manufacturer while secretly buying Chinese weapons for the US government. But when Vector went out of business in the late 1990s, papers revealed that it had been doing its own illicit business as well. The firm bid on its own account for a batch of North Korean missiles, and in trying to sweeten the deal provided China with sensitive technical specifications on the US Stinger anti-aircraft missile.149

Information available from the DOD shows that the US has made use of SASI’s services, and supposedly those of Helmut Mertins, on at least sixteen occasions during its wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Between 2000 and 2009, SASI won contracts from the DOD worth $45m, mostly for ammunition and small arms. By far the largest contract was placed in 2004 and ran until February 2007: at a total cost of over $35m, SASI was contracted to deliver ‘miscellaneous weapons’ to the USA Material Command Acquisition Center headquartered at Fort Belvoir in Virginia.150

* * *

But of all the weapons dealing in the US wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, none was more intriguing and lurid than that of Dale Stoffel. On 8 December 2004, Stoffel, a strapping arms merchant with an insatiable appetite for adventure, was shot dead on the outskirts of Iraq. His colleague, Joseph Wemple, driving the vehicle in which they were travelling, was shot once in the head at distance – possibly by a sniper.151 Stoffel was shot repeatedly in the front and back. His laptop and other personal effects were stolen. The crime scene was grisly: blood drenched their car, the front of which had crumpled like paper as it careened to a sudden stop, the windscreen, pocked with gunshot, cracked.152

Theories abound as to who killed Dale Stoffel. His tragic story will remain a symbol of the violence and flux of post-invasion Iraq, and the undertow of corruption and double-dealing that so often accompanies arms dealing amid the chaos of conflict.

Dale Stoffel lived his life in the military and in the murky world of intelligence and arms dealing. Entering the military as a means to pay for college, he swiftly rose through the ranks as a respected technical specialist with a highly prized mathematics degree. In 1987, he cemented his credentials when he examined the wreckage of USS Stark, which had been sunk in the Persian Gulf. Looking through missile fragments like tea leaves he was able to divine that the ship had been struck by two missiles rather than one – suggesting a premeditated attack rather than a simple accidental misfire.153 By 1989, Stoffel had left the employ of the military and had begun working for a number of defence contractors, including Raytheon and Mesa/Envisioneering.154 He filled a unique niche as a result of his training – he was knowledgeable about Eastern bloc weapons and able to procure sophisticated weapons systems, available following the fall of the Berlin Wall. The systems would be aggressively studied for any technical tips, as well as providing the military with valuable information about their capabilities before they entered the free market.

Six years later, Stoffel decided to enter the arms market on his own account. In 1995, he formed a company called Miltex, through which he was able to continue his niche purchasing. He was forced to drop the name in 1999 when Human Rights Watch reported on a shipment of Bulgarian weapons to an unnamed African country that was then under embargo.155 The shipment, stopped before it was able to leave Bulgaria, had papers listing Miltex as the broker.156 Stoffel denied ever being involved in the deal, claiming that another dealer must have used his name and company stamp to undertake the deal157 – a not unreasonable claim considering Stoffel’s daily contact with sometimes unscrupulous brokers in Eastern Europe. He dropped the Miltex name and reformed his enterprise as Wye Oak Technologies.

It was under that name that Stoffel attempted to make his fortune in Iraq. In 2003 he hired the services of BKSH,158 a powerful lobbying group based in Washington that was part of Burson-Marsteller, the largest public relations company in the US.159 BKSH had a number of clients certain to be influential in post-invasion Iraq. They included the Iraqi National Congress (INC), led by Ahmed Chalabi, one of Iraq’s most powerful politicians in exile. Chalabi had, throughout his period in exile, cultivated strong links with Republican leaders and intelligence agencies in the US, who believed that Chalabi could assume the reins of the country once Saddam fell. As a consequence, Chalabi’s INC received roughly $40m in support and aid from the US government – and motivated Chalabi to push fervently for a US intervention in the country.160

Chalabi’s importance to the Bush administration was made clear in February 2003 when Colin Powell delivered his ill-fated ‘call to war’ speech to the UN in which the US outlined its intelligence that Iraq had weapons of mass destruction.161 A crucial piece of evidence was the testimony of Mohammad Harith, an alleged Iraqi defector who claimed to have invented mobile labs that could research and produce biological weapons. But Harith, according to the investigative journalist Aram Roston, was a ‘known fabricator’ who had been served up to the US by Chalabi, who, at the time, was desperate for ‘intelligence’ that would motivate the invasion of Iraq.162 ‘Mr Chalabi and his cronies gave phoney information about weapons of mass destruction to the White House and the Defense Department bought it hook, line and sinker,’ Democrat Representative Jay Inslee would dramatically inform the House in 2004.163

In January 2004, Stoffel was convinced by BKSH lobbyist Riva Levinson to travel to Iraq in search of lucrative contracts. A few weeks later, he arrived in Baghdad to be looked after by Margaret ‘Peg’ Bartel, who had an agreement with BKSH to help newly arriving Americans with transport and board. Stoffel quickly fell in with the BKSH–Iraqi National Congress set, and was frequently seen with Ghazi Allawi164 – a relative of Ahmed Chalabi and a member of the powerful Allawi family, who came to fill numerous Cabinet posts in Iraq’s post-invasion government. In May 2004, for example, Ayad Allawi, Ghazi’s cousin, was appointed Iraq’s interim Prime Minister. Another brother, Ali Allawi, would serve as Minister of Defence in a Cabinet appointed by the Interim Iraq Governing Council between 2003 and 2004 and as Minister of Finance from 2005 to 2006. Ayad emerged again as a crucial power broker, as leader of the largest party after the disputed March 2010 elections.

Ghazi Allawi was, at some stage in his career, involved in a Panamanian business with Leonid Minin’s one-time partner, Erkki Tammivuori. The company was the Central Iraq Trading Company, suggesting that the Finn was also interested in doing business in Iraq.165

Despite these connections, Stoffel struggled to crack the Iraqi weapons market. It took six months to secure his first deal. In June 2004, the Multinational Security Transition Command–Iraq (frequently referred to by its nickname ‘Mitskey’) was investigating options related to Iraq’s existing weapons stockpile.166 Large amounts of it had rusted and decayed in Iraq’s deserts, sitting useless and unusable, while some was salvageable. An idea was developed to refurbish the items that could be saved, defraying the cost by selling the unusable items as scrap metal. The earnings potential was huge: Stoffel had estimated the value of all scrap metal from Iraqi arms to be worth roughly $1bn, if not more.167 With the go-ahead of General David Petraeus, who headed Mitskey, the Iraqi Ministry of Defence proceeded with the deal. Stoffel was granted access to various bases to inventory the equipment and, in August 2004, he signed an agreement with the Iraqi defence ministry to undertake the job. For his services as broker, Stoffel was to receive 10 per cent of the cost of refurbishment and any scrap sales168 – an income of $100m or more, even though US, but not Iraqi, regulations outlaw contracts with such percentage payments.169 Regardless, Stoffel had hit the jackpot.

But things soon started to go wrong. As part of the agreement, the Iraqi Ministry of Defence claimed that Stoffel could not be paid directly. Instead, a third party would be paid by the ministry, which would, in turn, pay Stoffel. The third party was the General Investment Group,170 headed by a Lebanese businessman, Raymond Zayna, and staffed by Mohammed abu Darwish, the one-time foreign affairs attaché for the Lebanese political party Lebanese Forces.171 Darwish would later be blacklisted by the Pentagon for running a scheme to defraud the US of millions of dollars.172

In October 2004, Stoffel submitted his first invoice to the Iraqi government, charging just under $25m for refurbishing services he had undertaken and would continue until January 2005. He never received the money. Furious and fretful, he travelled back to the US and petitioned his local representative, the Republican Rick Santorum. Santorum fired off a letter to Donald Rumsfeld, the result of which was a meeting between Stoffel and Rumsfeld scheduled for December 2004.173 A few days later, Stoffel was ‘invited slash ordered’ to travel back to Iraq by the Coalition military.174 On 5 December, a further meeting was arranged in Baghdad to sort out the payment issues, attended by a range of Iraqi and US brass. The meeting was tempestuous but the outcome was that Stoffel would receive an immediate $4m payment from Zayna with more to follow. ‘He left me a message on my voicemail,’ an associate recalled, ‘in which he was exuberant. Everything was solved.’175 Three days later, Stoffel was dead.

A few months later an Iraqi group calling itself ‘Rafidan – the Political Committee of the Mujahideen Central Control’ released a video claiming responsibility for Stoffel’s assassination. Asserting that ‘the devil Stoffel’ was a ‘shadow CIA director’ in Iraq, Rafidan drip-fed documents from Stoffel’s stolen laptop via its website. The group claimed that Stoffel had been assassinated to prevent him from raping the treasury and assets of the Iraqi people. One document in particular painted Stoffel in a less than flattering light. It was a memorandum of understanding (MoU) dated 20 June 2004 entered into between Stoffel, Ghazi Allawi, Mohammed Chalabi and the Turkish arms dealer Ahmet Ersavci.176 The MoU stated that ‘the parties to this MoU are endeavouring to establish Mr. Stoffel as the exclusive broker to the Iraqi Ministry of Defence with respect to the disposition of all military arms and weapons, including inventories, acquisitions and procurements’.177 Stoffel, in other words, would be the sole weapons broker to Iraq. It was envisioned he would operate via a company, Newco, established by Ahmet Ersavci.178 Newco, in turn, would earn a 10 per cent ‘brokerage fee’ on the value of all transactions – a potentially astronomical sum.179 Of this fee, 50 per cent would be retained in the company, while the remaining 50 per cent would be split, with Stoffel taking 60 per cent and the rest of the partners dividing the balance.180 If the MoU was accurate, it meant that Stoffel was involved in a contract that would have netted both himself and a series of politically connected Iraqis vast amounts of money.

With Rafidan claiming responsibility, the mystery of Stoffel’s death appeared solved. But many were not convinced. Nobody had heard of the Rafidan mujahideen. They had not claimed any other attack before Stoffel’s death and have never claimed one since. The ‘lawyerly’ manner in which the documents were presented online – replete with a video walking the audience through the documents – was most unlike what one would expect from a rag-tag group of insurgents and street fighters. Ghazi Allawi had also been taken hostage for twelve days, the month before Stoffel was killed, again by a formerly unknown group, Ansar al-Jihad (‘Partisans of Holy War’). After his release the matter was quickly forgotten about.181

What is certain is that Stoffel had more enemies in Iraq than just an unknown group of insurgents.

Frustrated by his exclusion from contracts in the first half of 2004, Stoffel had started to blow the whistle on companies and the US administrators doling out contracts on behalf of the CPA. What he witnessed in the chaotic days following the invasion confirmed to him that Iraq and the CPA were riddled with corruption: he would frequently complain of deliveries of cash hidden in pizza boxes from contractors to administrators at the CPA. In fact, according to affidavits submitted by his family, Stoffel had been ‘working and cooperating with Mr. [Stuart] Bowen’182 of the Office of the Special Inspector General for Iraq, the independent watchdog with powers to investigate corruption in Iraq. In 2009, the New York Times reported that, on 20 May 2004, Stoffel had signed an agreement with the Special Inspector General giving him limited immunity from prosecution in return for information.183 Curiously, Stoffel was due to meet Bowen on 10 December to discuss matters relating to his contract in Iraq – only two days before he was gunned down.184

In 2009, cryptic clues emerged as to who Stoffel may have been planning to finger. In February, the New York Times reported that the Special Inspector General had started to look more seriously into allegations of corruption levelled at members of the CPA. This included, according to officials in Iraq, revisiting the allegations of corruption levelled by Stoffel.185 At the same time it was reported that two senior and high-ranking members of the CPA had been subpoenaed to provide their bank statements as part of an investigation into bribes and kickbacks. One of these officials was Colonel Anthony Bell, who worked as the contracting officer for the CPA in Baghdad from June 2003 until March 2004.186 Attached to court papers supporting the subpoena was a statement from James J. Crowley, a ‘Special Agent’ for the Special Inspector General for Iraq Reconstruction, confirming that ‘SIGIR received information from a confidential source that Anthony Bell and another individual were improperly receiving kickbacks in connection with certain contracts entered into in Iraq. The confidential source was killed in Iraq after he met with US officials.’187 It is assumed that this is a reference to Stoffel.

The suspicions aroused by Dale Stoffel’s death and the questions that remain unanswered reflect that the days after Iraq’s liberation were, like the shadow world of the arms trade, defined by greed, corruption, opportunism, deception and violence. There were stratospheric profits to be made but in seeking them you were likely to put yourself in a position to pay the ultimate price.

* * *

In June 2011, President Obama announced a new timeline for troop withdrawal. Over 33,o00 troops, who had been redirected from Iraq to Afghanistan in a ‘surge’ in 2009, would be returning home by 2012.188 This would leave roughly 70,000 troops in the country. The stated plan is to remove all troops by 2014,189 but this claim has been undermined by more recent reports of the ‘secret pact’ between the US and Afghan governments to keep thousands of service members in the country until 2024.190 Either way, the US will still be involved for a few years yet, adding to the costs of war with every passing day.