6. Diamonds and Arms

The ‘pacifist’ der Hovsepian and Nicholas Oman were but two of many members of the Merex network who were actively involved in arms trafficking in Africa, the conflict-ridden Mecca for the trade. The network was well-connected in the less stable regions of the continent, counting among its agents the notorious Liberian warlord-President Charles Taylor and his brother Bob, an employee of Barclays Bank.1

With his considerable connections, Taylor was able to manoeuvre himself into power in the small West African state that had been formed by ‘free slaves’ given leeway by the US to return to their ‘homeland’ from 1821. His battle to achieve and maintain power turned an already impoverished nation into a brutalized killing field. Its horrors were spread into its resource-rich neighbour Sierra Leone, unleashing a whirlwind of human brutality: amputations, mass killings, beheadings and ritualized murder – all made possible by a network of arms dealers, diamond smugglers and timber merchants who populated the shadow world. Most were thuggish criminals moving in the crevices of international legal jurisdiction. Some were more organized, such as the network of arms dealers linked to Merex and the web of Al Qaeda diamond dealers that used Liberia to turn streams of foreign currency into the most mobile asset in the world.

Taylor’s background gave little hint of his later endeavours. Born in 1948 just outside the Liberian capital of Monrovia, he was the third of fifteen children in an American-Liberian household.2 His father had a stable job as a schoolteacher and as a result the Taylor family were able to live a solid middle-class lifestyle. Charles initially followed in his father’s footsteps, starting his training as a teacher. However, in 1972 he relocated to the US – the promised land of Liberia’s elite – to study economics at Bentley College, ten miles from Boston.3 During his five years at Bentley, Taylor gained a reputation among his US classmates as a feisty leader, impressing himself upon local political circles.4

Taylor’s education guaranteed him a place at the banquet table of the Liberian elite, undoubtedly aided by his political sympathies. During a demonstration in New York in 1979 he made public his distaste for the then President of Liberia, William Tolbert. The following year he travelled to Liberia, where he actively supported the military overthrow of Tolbert by Samuel Kanyon Doe, who would rule Liberia by diktat for the next decade. Later Taylor would have a hand in Doe’s overthrow. But in 1980 Taylor was a loyalist and was given a senior position in Doe’s government overseeing all public acquisition.5 His star waned shortly afterwards when he was accused of using his government post for rampant embezzlement, siphoning off $900,000 into his personal accounts.6 These accusations forced him to flee the country in the early 1980s under threat of prosecution. He re-established himself in his old stamping ground of Massachusetts, where he was a wanted man after Liberia requested his extradition. He was arrested in 1984 and held in the Plymouth County Correctional Facility.

Jail could not hold Taylor for long. The following year he escaped from Plymouth County in circumstances that remain mysterious. One account has it that Taylor banded together with four other inmates to saw through their cell bars and escape using knotted bed sheets, with Taylor paying $50,000 to be part of the plan.7 However, the ease with which he escaped and was able to quickly move abroad has belied the idea of a simple jailbreak. Assistance may have been forthcoming from more official quarters. According to Taylor’s own account he did not escape but was rather ‘released’ with the help of US intelligence agencies.8 He recalled that he was led out of his cell in the maximum security section of the prison and walked into the minimum security section, where he was allowed to climb out using roped bed clothes. Outside he found a car ready to take him around the US.9 The CIA has denied any complicity in the escape,10 but the agency’s denial is undermined by two facts. Only a few days after his escape Taylor’s Liberian ally Thomas Quiwonkpa, who had allegedly received limited US backing, attempted to overthrow the President, Samuel Doe.11 And secondly, Taylor was able to travel unhindered from Plymouth County to Washington, then Atlanta and finally Mexico, despite using his own passport.12

He swiftly returned to Africa with the intention of overthrowing Samuel Doe and seizing power in Liberia. He was received sympathetically in a number of countries, including Burkina Faso, where he joined forces with various Liberian exiles, most notably Prince Johnson, a would-be warlord who had been part of Quiwonkpa’s failed attempt to overthrow Doe. They formed the National Patriotic Front of Liberia (NPFL), a group that would oversee the country’s brutal misery for fifteen years. With military training and ambitions the Liberian exiles caught the attention of the Burkinabe presidential hopeful, Blaise Compaore, who asked for help in overthrowing the President of Burkina Faso, Thomas Sankara. The support of President Houphouët-Boigny of the Ivory Coast added impetus to the plan. On 15 October 1987 Sankara was killed by a Burkinabe squad that included a number of Liberian operatives, one of whom was Prince Johnson.13 Many suggest that Taylor had an active role in the murder.14 As a consequence, when he was preparing to invade Liberia two years later, Taylor could rely on Burkina Faso and the Ivory Coast for support, initially diplomatically and later as a channel through which arms and supplies could be delivered.

This support provided Taylor and the NPFL with considerable diplomatic cachet. But what they needed was a benefactor who could provide more than diplomatic cover. They found this in the figure of Libya’s maverick dictator, Muammar Gaddafi. In 1987, Taylor travelled to Libya, where he and his Liberian partners were inducted into Gaddafi’s World Revolutionary Headquarters,15 a training camp for those groups Gaddafi wished to see achieve their national ambitions, as well as his own megalomaniacal vision.16 As an oil-rich state often involved in military intrigue, Libya was able to provide Taylor and the NPFL with what they really needed: military training, weapons, ammunition and millions of dollars.

At the same time Gaddafi was overseeing the creation of the Revolutionary United Front (RUF), a sadistic group who were preparing to take over Liberia’s diamond-rich neighbour, Sierra Leone, by force.17 Taylor befriended the RUF leader, Foday Sankoh.18 It was to be a fateful friendship. Between 1990 and 2005 the RUF and NPFL would symbiotically feed off each other’s resources to take control of their respective countries, in one of the world’s most bountiful diamond-producing regions.

On Christmas Eve 1989, Charles Taylor and the NPFL made their move. Their aim was simple: progress through the countryside, gather supporters and overthrow the existing dictator while taking control of the capital, Monrovia. His swift march through Liberia was aided by the cheering support of locals, some of whom believed he would remove the genuinely unpopular Doe and install a form of responsible government. A number of the so-called ‘country people’ were driven by their antipathy towards Americo-Liberians, while others were fuelled by the temptation of looting. Taylor later recalled that as the NPFL advanced into Liberia ‘we didn’t even have to act. People came to us and said: “Give me a gun. How can I kill the man who killed my mother?”’19 By June 1990, the NPFL had reached the capital and victory seemed assured.20 Samuel Doe, whose presidency had been inaugurated with the murder of the former President Tolbert, was to suffer a similar fate. A splinter group of the NPFL led by Prince Johnson instead of Taylor, stormed into Doe’s office. Over the course of a number of excruciating hours Doe was viciously tortured. As his ears were cut off amidst blood-curdling screams an insouciant Johnson sipped on celebratory Budweisers, demanding to know the dictator’s banking details.21 The grisly video of the murder was quickly reproduced and sold in huge numbers throughout West Africa.22

Just as Taylor believed that his blitzkrieg assault on Liberia had succeeded, his advance was blocked by interference from other West African states. A number of them, Nigeria in particular, worried about the impact of Taylor’s accession on the balance of power in the region: with Taylor backed by Burkina Faso and the Ivory Coast, Nigeria’s role in regional politics would be considerably weakened. Therefore, to prevent Taylor and the NPFL seizing power, a nominally independent force was put together by the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS). Most of the troops were provided by Nigeria. When the regional body’s monitoring group, ECOMOG, was deployed, Taylor’s forces were already in Monrovia but had been unable to take the presidential palace. ECOMOG immediately reclaimed some of the territory Taylor’s forces had gained. It was a setback that Taylor would turn into a long-lasting grudge.

By the end of 1990, the warring parties had reached a stalemate. Monrovia was under the control of ECOMOG troops, a number of whose officers pursued criminal and business interests in the capital – which provided a powerful motivation for continuing the war. Prince Johnson’s NPFL splinter group had set itself up in a corner of Monrovia, failing to make any meaningful impact, while Charles Taylor, by virtue of his political nous and constant access to radio production facilities and the international news media, established himself as the pre-eminent leader of the NPFL. He formalized the area under his control, naming it Greater Liberia, and operated a virtual second state from this base.23

His control over Greater Liberia gave Taylor the perfect opportunity to consolidate his power and earn considerable amounts of money. He ensured that one of the biggest employers in the area, the Firestone Tyre company, returned to operation. By 1992 Firestone was turning a good profit and paying Taylor’s NPFL $2m a year for ‘protection’.24 It was later alleged that a number of the warlord’s most notorious operations were launched from the properties of Firestone.25 Taylor also oversaw the re-emergence of the Liberian timber sector, whose ‘taxes’ further boosted his ‘second state’. Besides demanding that foreign businessmen build roads and other necessities, Taylor also took a cut of every business deal. It was estimated that he extorted between $75m and $100m every year in this way, with his loot secreted in personal accounts throughout Africa.26 It was a system that Taylor would perfect when he was eventually elected President in 1997.

Taylor’s relationship with the Revolutionary United Front (RUF) in Sierra Leone further fattened his bank accounts and aided his military effort. The RUF was the spitting image of the NPFL. It was constituted by a small handful of Sierra Leonean exiles and had been officially established at Muammar Gaddafi’s World Revolutionary Headquarters. In 1991, the RUF invaded Sierra Leone assisted by the NPFL.27 Ostensibly it sought to take political power, symbolized by the overrunning of Freetown, the seat of government. But of greater importance was control over large swathes of the countryside that offered glittering wealth in the form of diamonds. The RUF ‘remained a bandit organization solely driven by the survivalist needs of its predominantly uneducated and alienated commanders’.28

As a well-armed group of bandits and thugs the RUF was as brutal as the NPFL, using child soldiers to fight many of its wars. Local citizens were forced into compliance and servitude in an orgy of amputations and rapes. Slave labour was also used to translate the diamonds into the real currency in the region – weapons. Local citizens were forced to walk from the diamond fields to the porous border of Liberia and Sierra Leone, where diamonds were given to the NPFL and crates of weapons handed over in return. Without rest and under the constant threat of beatings if they stumbled, most of the human mules used by the RUF died within a couple of months.29 For Liberia it meant a massive increase in diamond exports, even though diamond production in the country was minimal. In Sierra Leone official diamond exports fell from 2 million carats per year in the 1960s to a risible 9,000 carats in 1999.30 Liberia was suddenly exporting 6 million carats annually by the early 2000s, even though it could only produce 200,000 carats from its own diamond fields.31

To maintain both his military challenge for power in Liberia and his support for the RUF, Taylor needed a range of interconnected services from the early 1990s: arms dealing, diamond smuggling and money laundering. Each was complicated by international approbation, especially weapons dealing, which was criminalized by a UN arms embargo in November 1992 that prohibited the sale of arms to any side in the Liberian conflict.32 To secure these services Taylor used the interconnected web of Merex agents, becoming an agent himself in the process.

* * *

Nicholas Oman, the Australian-Slovenian arms dealer who had been a part of the Merex network in the Balkans, was involved in Liberia from 1992. He allied himself with Charles Taylor and supplied him with weapons. This relationship revealed itself in a number of related ways. While Nicholas Oman was stripped of his diplomatic relationship with Liberia in 1996, just prior to Charles Taylor’s election to the position of President, his son, Mark Oman, was appointed the official representative of Liberia in Australia soon after, a position he held until Taylor’s fall from power.33 Mark also continued to run his father’s company, Orbal Marketing, in Liberia,34 and even announced a fire sale of diamonds in violation of international embargoes in 2003,35 suggesting that the Oman family remained in close contact with Taylor and the NPFL.

Nicholas Oman worked closely with the relatively unknown Taylor Nill, who (falsely) presented himself as an ambassador for the US in Liberia. Nill would later emerge as an important player in International Business Consult (IBC), along with other shareholders such as the RUF’s Ibrahim Bah and Charles Taylor himself.36 IBC was the vehicle Taylor used to secure a substantial amount of arms using the extended Merex network. This was confirmed by Roger D’Onofrio. Holding joint US–Italian citizenship, D’Onofrio was frequently fingered as a CIA agent who had retired from active service in the early 1990s.37 He both affirmed and denied his CIA connections, flip-flopping as the situation required. After his ‘retirement’ from the CIA, D’Onofrio settled in Naples and busied himself in the affairs of Italy’s criminal and Mafiosi elites, where he met a man who would become his close confidant, the Catania lawyer Michele Papa.38

Papa had made a name for himself in Italy through the 1970s and 1980s for his role as a go-between for Italian business and Libya. From the 1970s, Libya had bought significant stakes in Italian enterprises, at one time holding 13 per cent of the shares in Italy’s mega-corporation, FIAT.39 In the 1980s, Italy was the second-largest importer of Libyan oil, just behind America.40 As a result of this economic activity Libya needed Italian intermediaries and Michele Papa rose to become one of the most influential of these, a position cemented by his heading the Sicilian–Libyan friendship organization and overseeing the building of the first mosque in Italy.41 His role was not without controversy, as the French daily Le Monde reported:

He periodically organizes Italian–Libyan friendship fetes with gigantic portraits of [Gaddafi] and President Sandro Pertini, thus stirring up protests from the presidency of the Republic [of Italy]. He has also enabled Libyans to obtain indirect control of two local television stations in Sicily. In his newspaper, Sicilia Oggi, he extols the achievements of the Libyan Revolution and sings the praises of its leader.42

Papa’s links to Libya embroiled him in the so-called ‘Billygate’ scandal in the US in the late 1970s, which was named after the bumbling brother of President Jimmy Carter. From the early 1970s, Libya had been stifled by its acrimonious relationship with the US administration, reflected in the halting of weapons and aircraft purchases worth $300m.43 What Libya needed was a friendly ear in proximity to the White House. Billy Carter’s was available for purchase. In January 1978, Papa invited the President’s brother to visit Libya. Over the next twelve months Carter made a number of visits in the company of Papa, even forming his own version of Papa’s association, the Libya–Arab–Georgia Friendship Society.44 So aggressive was Billy in his promotion of Libya that he was forced to register as a foreign agent with the CIA.45 When news broke that he had received a loan of $220,000 from his new friends, all hell broke loose in Washington. Although Jimmy Carter was eventually cleared of ever being sus- ceptible to the sales pitch of his brother, ‘Billygate’ overshadowed his presidency just as his campaign for re-election against Ronald Reagan was beginning.

In 1992, Papa and D’Onofrio set their sights on Africa. Through IBC they aimed to engage in the import and export of various products.46 Papa suggested that they operate from Liberia, a country with close links to Libya. ‘Liberia has always been a great country for offshore finance deals,’ D’Onofrio enthused to Italian interrogators.47 D’Onofrio put the plan in motion by travelling to Foya in Liberia, a province controlled by Charles Taylor which borders Sierra Leone and Guinea. There he met with Taylor and the Libyan-trained RUF leader Ibrahim Bah.48 For Taylor, IBC was the perfect company through whom to acquire arms and sell his diamonds. ‘Taylor and I spoke at length with Bah, and we decided that IBC would be used to get arms for them,’ D’Onofrio recalled.49 IBC would pay for the arms in smuggled Sierra Leonean diamonds, carried into Liberia by the RUF’s slave labour. To convince the warlord of their bona fides, Papa and D’Onofrio transferred 50 per cent of IBC’s shares to Charles Taylor and his associates, ensuring that half of any profits made would be recycled back into the accounts of Taylor and co.50 In 1993 alone the company made a profit of $3m.51

None of the parties to the IBC agreement knew how to organize money transfers in a way that would obscure the origins of their ill-gotten gains. Nor did many arms dealers trust Taylor and Bah to make good on their promise to supply diamonds. One man provided the solution. Dennis Anthony Moorby, himself a Merex agent,52 was the chief executive officer of Swift International Services based in Canada, which had signed a number of working agreements with IBC in the early 1990s.53 According to a joint investigation by Italian and Canadian police services, Moorby was deeply connected with Mafia families in the United States, including the infamous Gotti family and the Gambino clan.54 Moorby appointed one Francesco Elmo as legal officer for Swift International Services.55 Elmo was a well-connected Italian arms dealer who, when apprehended, provided detailed evidence to Italian authorities that helped unravel the activities of the like of Nicholas Oman, Franco Giorgi, Joe der Hovsepian, Gerhard Mertins, as well as D’Onofrio and Moorby.

Through an intricate system of credit lines based on pre-war German bonds and valuable minerals held in banks in the US and elsewhere, Swift assisted IBC to effectively launder Liberia’s diamonds, providing a clean pile of money with which to buy arms. The effectiveness of the system was illustrated in 1993 when an order was placed with clean money for a range of ammunition and guns to be supplied to IBC by a Swiss contact with the Bulgarian arms manufacturers Kintex. The arms were delivered to Liberia disguised as an innocuous load of oranges and olives.56

Kintex was linked by Western officials to major drug and weapons trafficking from at least 1985 onwards. In the early 1990s, it was reportedly Bulgaria’s single largest foreign exchange earner. In the late 1980s, BNL, a bank used by the US to channel funds to Saddam Hussein, gave two unsecured loans to Kintex to buy equipment on behalf of Iraq – one for $30m and another for $11m. The first was used to purchase computer equipment which later turned up at an Iraqi complex known as Al Hatteen, where Iraqis were allegedly working on high explosives as part of its nuclear weapons experiments. The $11m was used to purchase electronic equipment, material and machinery on behalf of the Iraqi defence ministry.57

* * *

By the mid-1990s, matters in Liberia had reached a stalemate. ECOMOG forces had pushed Charles Taylor further back into the countryside. At one time it seemed that he might even be dislodged from the country entirely. But Taylor frequently regrouped, pushing ECOMOG back in turn and threatening the fragile peace that held in Monrovia. Taylor’s relationship with Nigeria began to improve after the departure of President Babangida in 1993. By late 1996 it was clear that Nigeria would allow Taylor a crack at the presidency via an election. In August 1997, seven years after he had first invaded the country, Charles Taylor was elected President. The NPFL won nearly 75 per cent of the vote in a campaign that was marked by their supporters’ chants of ‘He killed my pa, he killed my ma, but I’ll vote for him.’58 That a brutal warlord could win so overwhelmingly in a generally free and fair election may seem incomprehensible. But for many in Liberia granting Taylor power seemed the only way to end one of Africa’s most brutal conflicts.59

Hopes of peace were quickly dashed as Taylor faced continuing insurgencies against his rule, especially from 1999 onwards. He also continued his support of RUF rebels in Sierra Leone, reaping the benefits of their mutual kleptocracy. As President, Taylor stepped up the systems he had developed to perfection in Greater Liberia, earning considerable income from timber production and mineral extraction. His needs during the civil war were replicated in the post-election period: arms, diamond smuggling and money laundering. Unfortunately for Taylor much of the network he had used prior to 1997 had dissipated by the time he won power. While Nicholas Oman was forced to flee the Balkans to escape the clutches of Radovan Karadzic, others had been apprehended. By 1996, the Italian police had stitched together a sprawling patchwork of international criminality as part of an investigation known as ‘Cheque to Cheque’. Arrest warrants were issued for key players in the extended Merex network, including Oman, Moorby, Roger D’Onofrio and Swift International’s Rudolf Meroni. While none were ever prosecuted, the arrests, temporarily at least, disrupted their activities.

Fortunately for Taylor there were others equally nefarious, delighted to step into the breach. A retired Israeli Defence Force Colonel, Yair Klein, provided matériel and training to Liberia’s Anti-Terrorism Unit and, in violation of the UN arms embargo, to the RUF as part of a diamonds-for-arms operation involving two other Israelis, Dov Katz and Dan Gertler. In January 1999, Klein was arrested in Sierra Leone on charges of smuggling arms to the RUF.60

In September 1998, Taylor had a fateful meeting with an insalubrious Ukrainian-Israeli, Leonid Minin.61 Born Leonid Bluvstein in Odessa, Ukraine, in 1947, Minin followed the route of many Jewish Russian émigrés and settled in Israel, arriving via Austria. Around 1975 he moved once more, eventually receiving permanent residence while living in the town of Norvenich, close to Bonn and Cologne in West Germany.62

During the 1970s and 1980s, Minin had dabbled unsuccessfully in a variety of business activities. By the early 1990s, he appeared on the radars of investigative authorities in Italy and beyond. In 1992, Russian police investigated him for involvement in smuggling art works and antiques.63 Two years later a former model, Kristina Calcaterra, was caught at the border between France and Switzerland carrying a small bag of cocaine. According to Calcaterra the cocaine belonged to Minin, who had asked her to deliver it to him in Switzerland. In March 1997, he was arrested by police in Nice as he attempted to board his personal jet. He was carrying a small bag of cocaine, for which he received an eight-month prison sentence. This arrest alerted authorities in Monaco, where Minin had a number of businesses. In June 1997, he was informed by letter that he was no longer welcome in Europe’s glitziest principality. His German visa was also repealed and his name entered on the Schengen Index as ‘a person not to be admitted’ to this group of European states.64

His drug misdemeanours seem minor in contrast to his involvement in mafia activities in the Ukraine. The collapse of the Soviet Union provided a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for smart, tough criminals. The temporary collapse of the state, corruption among senior politicians and the rapid privatization of primary resources allowed mafia groups to seize control of highly valuable assets. The oil and gas industry was immediately lucrative because of the voracious export market.65 By the early 1990s, it was reported that 67 per cent of all oil exports from Russia were controlled by organized crime, whose tentacles stretched to the highest corridors of power.66 Odessa on the Black Sea was the gateway for much of the East’s oil and gas exports. In the early 1990s, the Odessa Neftemafija (oil mafia) took control of the town’s exporting facilities.67 Minin was ‘one of the most important’ members of the entire Neftemafija network. His companies, Limad and Galaxy, had a major foothold in the area, controlling large parts of the export trade. They were given a contract to build a refinery that would boost Odessa’s ability to refine Russia’s crude oil prior to export.68 In addition to making a fortune in the oil business, the broader mafia network under Minin’s control was also allegedly ‘involved in international arms and drug trafficking, money laundering, extortions and other offences’.69

While international police services struggled for hard evidence to turn these allegations into a prosecution, Belgian police believed they had gathered enough information to implicate Minin in a murder. In December 1994, a Russian entrepreneur, Vladimir Missiourine, was shot dead by three men in the Brussels suburb of Uccle. Belgian police traced a series of phone calls from Missiourine’s business to Minin’s Galaxy group. Missiourine, who was also suspected of links to Russian organized crime, had developed a business relationship with Minin before they fell out. Police uncovered an invoice sent by Missiourine to Minin’s Galaxy Energy, demanding a commission payment of $117,240. It had been sent to Minin’s company only four days before Missiourine was found murdered.70 However, as with most of the investigations into Minin, little hard evidence was presented that could definitively link the Ukrainian to the murder. He was free to carry on his business unhindered.

Given the company he kept and the activities he engaged in, it is hardly surprising that in the second half of the 1990s rumours abounded that elements of the Russian mafia had ordered a hit on Minin.71 As a consequence he was keen to expand his empire beyond Europe. In 1998, he had a chance encounter that would lead him to Liberia. Minin was in Ibiza exploring the potential for entering the real estate business, where he met a Russian estate agent, Vadim Semov. Semov introduced Minin to a close Spanish friend, Fernando Robleda. After lengthy conversations it became clear that Robleda could offer Minin an escape to Africa via his company Exotic Tropic Timber Enterprises (ETTE) in Liberia.72

Robleda had formed ETTE as a logging company in February 1997.73 To make serious profits the logging company required a licence, or concession, from the government. In May, ETTE was granted a concession to harvest the sizeable Cavalla Reforestation and Research Plantation in Liberia.74 Unfortunately for Robleda the concession had been granted by the opponents of Charles Taylor two months before he was elected President. Robleda’s concessions were ‘unilaterally’ revoked by the Liberian Forest Development Agency in November 1997.75 He had a logging company but no access to logs. It was a devastating blow for ETTE, especially as Robleda had already spent nearly half a million dollars in advanced taxes to the previous administration and on machinery.76

Robleda hoped that the arrival of new investors would not only inject capital into the company but also help to regain its Cavalla plantation concession. In September 1998, Minin travelled with Robleda to Liberia, where they met Charles Taylor. What happened at the meeting is contested: Robleda, when later interrogated by Italian police, recalled that he had travelled with Minin to Liberia but was not privy to any meetings between Taylor and Minin. Instead he claimed that Minin met Taylor a number of times over the course of the week. What they discussed remained secret, although Robleda says Minin continually remarked that he was ‘in debt’ to Taylor, suggesting some sort of deal had been struck.77 By contrast, Minin claimed that Robleda had attended the meetings and convinced him to pay ‘advance taxes’, effectively a bribe, directly to Taylor. The President then demanded a commitment to further commission payments in the future.78 Minin’s testimony was a clear acknowledgement that, coerced or not, he had agreed to play the corrupt game Taylor demanded of new entrants into Liberia.

Following the meetings events moved swiftly. An ETTE board meeting was held on 10 December at the Hotel Africa in Monrovia, the chosen meeting place of nearly every schemer, businessman and arms dealer in Liberia, even after it had been reduced to a shell during the civil war. At the meeting ETTE was reconstituted and its shareholding restructured. Minin now controlled 34 per cent while Robleda and his friend Semov held the rest. Confirming his seniority Minin was appointed chairman of the board of ETTE, Semov president and Robleda treasurer.79 Barely four days later, ETTE was granted the concession to harvest the Cavalla plantation. The agreement noted that ETTE was looking to acquire additional concessions, which the government indicated it would grant.80

It was a remarkable turnaround for the company, indicating the impact that Minin had on Taylor. In addition to cash payments Minin made clear to the bellicose President that he could also provide him with weapons. Within a week of the company receiving its concession Minin helped Taylor move a considerable stock of arms. It is assumed that the cache had been sourced by Minin in the Ukraine before being transported on two trips to Monrovia in December 1998. On the second trip the plane was loaded with 68 tons of ammunition and weapons which had cost roughly $1.5m.81 The weapons were quickly ferried across the border to be used in the brutal attack known as ‘Operation No Living Thing’ in early January.

In less than two weeks 6,000 innocent people were murdered and tens of thousands injured, most maimed for life. Over 500 buildings were destroyed by fire and ransacking, leaving a shell of a city.82 ‘There was a millenarian quality to the terror, random, ecstatic and finally comprehensive.’83

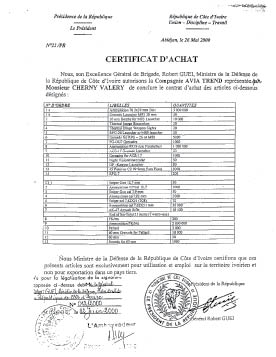

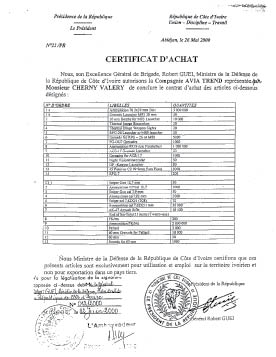

Minin’s successful gun-run, while brutal in consequence, was considerably smaller in scale than those that would follow. Over the next year and a half he conducted at least two further deals with Liberia and possibly another one which remains shrouded in mystery. The first involved another shipment of 68 tons of assorted arms: 715 boxes of weapons and cartridges, 408 boxes of cartridge powder, a smattering of anti-tank missiles, and RPG launchers and ammunition.84 The weapons had come from the Ukrainian state-owned company Ukrspetsexport. An end-user certificate dated 10 February 1999 indicates that the weapons were to be sold to a Gibraltar-based company, Chartered Engineering and Technical Services, and delivered to the Ministry of Defence in Burkina Faso aboard a giant Ukrainian Antonov 124. It was signed by Lieutenant-Colonel Gilbert Diendere, the head of the Presidential Guard of Burkina Faso.85 Some of the weapons remained in Ouagadougou while the rest were trucked to the town of Bobo Dioulasso. From 17 to 30 March, Minin used his jet to transport the weapons from the two depots in Burkina Faso to Liberia.86 Pictures later presented in court showed the weapons crates hastily buckled into plush leather seats.87

Whether Minin began arranging a second arms transaction in 1999 is still unclear, a situation that has suited Minin’s erstwhile business partner, Erkki Tammivuori. Tammivuori, a Finnish national, has a history of links to political power. His father, Olavi, was a prominent Finnish businessman who made his name developing opportunities for Finnish entrepreneurs in Turkey, becoming Finland’s Honorary Consul to Istanbul towards the end of the 1980s.88 Son Erkki also married into Finnish political royalty when he wed the daughter of Ahti Karjalainen, twice Prime Minister. Tammivuori followed in his father’s footsteps by establishing a number of business interests in Turkey. It was on the letterhead of one of these companies, MET AS, that Tammivuori corresponded frequently with Leonid Minin through 1999 and 2000.

Minin suggests he first met Tammivuori through one of his pilots, who was also Finnish, at a New Year celebration in Switzerland at the turn of the millennium.89 The written record suggests earlier contact. On 20 March 1999, Tammivuori faxed Minin asking whether he could source Ukrainian boats, including hovercraft, for the Turkish navy.90 Over the next year Tammivuori and Minin attempted a number of transactions in Liberia, facilitated not only by Minin’s contact with Charles Taylor but also the rapport that was established between Tammivuori and Taylor’s son, ‘Chucky’ or ‘Junior’.91 In June 1999, Tammivuori formalized his role as a ‘consultant’ to Minin’s companies92 as they explored opportunities in helping to privatize Liberian port and airport facilities.93 A fax sent to Minin by Tammivuori on 19 September 1999 confirmed that Tammivuori would buy ‘ten items of package [sic]’ that could be displayed to potential customers in Amsterdam. Italian prosecutors believed that the ‘ten items of package’ were most likely blood diamonds exported from Liberia and Sierra Leone.94

It was through Chucky Taylor, with Minin’s assistance, that Tammivuori is alleged to have organized his own weapons deal in Liberia. On 23 March 1999, Tammivuori wrote to Minin on a fax headed ‘“Konkurs” missiles procurement’ describing the opportunity as a ‘special one’. It detailed a potential transaction in which ‘“Konkurs” missiles would be procured (only missiles, no launchers), with a configuration [of] “TANDEM WARHEAD FOR REACTIVE ARMOUR”.’95 Tammivuori estimated that the ‘buyer’ would need eighty missiles, a hundred if the price was right. Intriguingly the Finn claimed that the transaction could be ‘done with End-User or without Certificate’, which suggested he would be happy to have the deal go ahead without any of the paperwork necessary for it to be legal.96 Later that year, Tammivuori wrote once again to Minin informing him that he had started to work on a ‘special package for JUNIOR’ and that he would be happy to deliver it ‘provided [Junior] can afford it’. Tammivuori asked Minin to open ‘a line of communication with JUNIOR in case I need it’ and confirmed that ‘the package consists of 20–30 items in addition to the 100 units you know about’.97 When interviewed, Tammivuori claimed that the deal did not involve Liberia but another potential buyer, whom he wasn’t prepared to name.98 However, one of Taylor’s right-hand men, Sanjivan Ruprah, showed UN investigators lists of all weapons that had been transported into Liberia in a shipment in May 2000, which included a range of missile types and a handful of Konkurs missile launchers.99

Minin’s final successful deal took place in mid-2000. This time the arms were to be delivered via the Ivory Coast, rather than Burkina Faso. On 14 July 2000, a giant Antonov-124 took off from the Ukrainian airport of Gostomel. Its cargo was a massive 113 tons, including ‘10,500 AK-47 assault rifles, 120 sniper rifles, 100 grenade-launchers, night-vision goggles and 8 million rounds of ammunition’.100 The weapons had, once again, been sourced from the Ukraine, this time from the state-run Spetsehnoexport. After a brief stopover the plane touched down in the Ivory Coast on 15 July. It was allowed to land on the basis of an end-user certificate signed by an Ivory Coast official, a signature procured on the understanding that, once the plane had landed, Liberia would give half the cargo to the Ivory Coast government. The cargo was transported from the Ivory Coast to Liberia using smaller aircraft under the direction of Taylor’s lieutenant, Sanjivan Ruprah.

Remarkably, 113 tons of matériel wasn’t enough for Liberia and the Ivory Coast. The July 2000 deal with Minin included a second consignment of weapons, which were standing ready to be delivered once the first shipment had been made. This was never to happen.

Figure 2: False end-user certificate used by Leonid Minin to transport weapons through the Ivory Coast to Liberia

Early the following month, while celebrating his recent sales to Liberia, Leonid Minin was unceremoniously arrested.101 ‘We raided the Hotel Europa, surprising Minin, who was in bed, nude, with four prostitutes who were also nude. And they were in the process of passing a drug vial around,’ the Police Chief of Cinisello Balsamo recounted.102 Supposedly a disgruntled prostitute whom Minin had failed to pay provided a random tip-off to the police.103 As the room was searched police realized the flabby, stoned man they had arrested was more than just a low-life with a drug problem. Diamonds worth $500,000 were discovered, which Minin could not prove came from a legitimate source, along with a bag holding $35,000 in Hungarian, American, Italian and Mauritian currency. But the real goldmine was Minin’s briefcase of documents: nearly 1,500 papers in numerous languages painting a vivid portrait of his life as one of Liberia’s chief arms dealers.104

Although he had been followed by Italian police since the early 1990s, Minin was not at first recognized for the gangster he was. It was only a few days later, after the documents had been translated, that Minin’s real identity became clear. Charges were filed against him for drug offences, a prelude to indictment for illegal arms dealing. Minin would be out of action for a considerable period of time. Charles Taylor was down one arms dealer.

Minin’s arrest was not the only impediment to his operations in Liberia. His involvement in ETTE was also running into trouble. Under interrogation Minin claimed that Fernando Robleda had been cheating him of money, embezzling large amounts and leaving a ‘hole’ of $300,000 in the accounts of the business.105 Robleda claimed that, as soon as Minin had got involved, he had sent a bunch of Ukrainian ‘thugs’ to take control of the company. Over time the Spaniard was frozen out and feared for his life to the extent that he fled Liberia.106 By September 1999, Robleda had found an alternative partner in the form of a company called Forum Liberia, which had been created earlier that year.107 Minin agreed to relinquish his hold on ETTE if he was bought out by the new partner. Forum Liberia agreed to pay him $5m, disguised as an agreement to purchase plant and machinery. It would have been a smart profit of over $4m on the $900,000 Minin had originally invested. Robleda believed this would be enough to get Minin to leave the business. Instead, the Ukrainian pocketed an upfront payment of $1.5m and, according to Robleda, refused to hand back the forestry concessions or relinquish his shares. It was easy for Minin to hold on in this way as Forum’s agreement with him had specifically eschewed talk of transferring ownership as they were keen to hide their involvement in the Liberian logging industry because an embargo on Liberian wood products was in place. Months after Minin had been arrested Robleda was still writing to him frantically to convince him to withdraw from ETTE, which would allow Robleda to continue working with Forum Liberia.

Unfortunately for Robleda, in May 2006 the Spanish holding company of Forum Liberia, known as Forum Filatelico,108 was discovered to be a massive scam.109 Forum Liberia, needless to say, was finished.

* * *

Minin’s personal, legal and commercial difficulties, together with his extensive drug use, had made him erratic and unreliable for years before his eventual arrest. Mimicking his boss’s behaviour, one of Minin’s pilots was too drunk to fly a load for the Liberians. Charles Taylor was furious. His son, Chucky, knew of a Russian who registered some of his planes under the Liberian flag and claimed to be able to deliver anything to anywhere. He contacted Viktor Bout, who quickly arranged a pilot to assist the Taylors.110

Bout, known by a number of aliases, including Boutov, But, Budd and Bouta, was the most notorious arms dealer of the late 1990s and early 2000s. Born in 1963 in the small town of Dushanbee in the USSR,111 Bout was highly proficient at languages, enrolling at the Soviet Union’s Military Institute of Foreign Languages after his basic military training, reaching the rank of Lieutenant.112 The institute, where he held senior rank, was closely connected to Russia’s infamous GRU, the country’s largest foreign intelligence service. Bout’s father-in-law was a senior member of the KGB, perhaps even serving as one-time Deputy Chairman of the feared security service.113

Fluent in six languages and capable of flying a variety of aeroplanes, Bout decided in 1991 to pursue a career in the freighting business, a popular endeavour in the chaotic times following the fall of the Berlin Wall.114 Acquiring planes was easy. Surplus military matériel was freely sold by army officials keen to make a quick buck, so Bout was able to purchase three massive transport aircraft for a mere $120,000.115 Bout chroniclers Douglas Farah and Stephen Braun suspect that the Russian may have got the planes so cheap, along with an extensive and detailed list of ex-Soviet weapons clients, as a result of support from the KGB.116 Russian military officials often declared planes unusable and sold them for scrap, despite the fact that they were fully operational, enabling Bout to rapidly grow his fleet to fifty planes.117

By 1992, Bout had entered the feral world of arms dealing. His first client was the newly installed Northern Alliance government of Afghanistan, who had previously fought a devastating war against nascent Taliban fighters. Bout travelled frequently to the treacherous country, where he came to know Ahmed Shah Massoud, a notable local politician, both warlord and poet, dubbed the ‘Lion of Panjshir’. Massoud and the gregarious Russian adventurer bonded over lavish dinners and a mutual affinity for hunting, which was often conducted from one of Massoud’s helicopters with sniper rifles. The relationship secured Bout a number of profitable arms deals in which he ferried Russian weapons to Massoud.118

Bout’s dealings with the Northern Alliance caused him considerable problems. On a routine flight in 1995, one of Bout’s air freighters carrying ammunition to Kabul was intercepted and forced to land by an old MiG fighter jet belonging to the Taliban. Its occupants, all Bout employees, were taken hostage and the onboard matériel seized. In August 1996, the captured pilots supposedly overpowered their captors and fled. The escape was probably staged to secure the pilots’ freedom without diminishing the fearsome reputation of their captors, who had become clients of the Russian. Ever the salesman, while negotiating with the Taliban about his captured jet and crew, Bout persuaded them of his skills as an arms dealer. Over the next few years he delivered massive quantities of weapons to the Taliban from his base in Sharjah in the United Arab Emirates, netting an estimated $50m.119 He also helped the Taliban set up its own transport network by selling the organization a fleet of cargo planes in 1998.120 In the wake of 9/11 Bout’s relationship with the Taliban would make him an international pariah.

However, before his business dealings with the Taliban, Bout had already broken arms sanctions in Bosnia. He supplied weapons to Muslim Bosnians who were facing the depredations of Serbian nationalists. The deals were funded by the Third World Relief Agency, a charity with links to Islamic extremists, including Osama bin Laden. Between 1992 and 1995, the agency handled over $400m.121 In September 1992, some of this money was used to hire an Ilyushin 76 to deliver a substantial cache of arms from Khartoum in Sudan to Maribor, an airport in Slovenia close to Bosnia.122 Bout owned the plane and was probably involved in the procurement of the weapons as well. So at the time at least three individuals linked to the Merex network – Bout, der Hovsepian and Nicholas Oman – were supplying arms to various participants in the Balkans conflict.

The fighting-ridden and resource-rich continent of Africa was a magnet for Viktor Bout, as it was and remains for most arms dealers. He transported a contingent of French UN peacekeepers to Rwanda in a belated and futile attempt to prevent the Rwandan genocide. His first major African client was the Angolan government, which was fighting a decades-long conflict with the one-time US and apartheid South African ally UNITA. Bout developed a close working relationship with the Angolan military, in particular the country’s air force. He supplied them with a wide range of matériel, creating a company in Belgium for the specific purpose. Between 1994 and 1998, Bout concluded contracts to the value of $325m with the Angolan air force.123 However, in 1998 the Angolan government discovered that Bout had been supplying its mortal enemy, UNITA, with a range of weapons from Bulgarian arms manufacturers. Bout made thirty-seven delivery flights to UNITA, paid for with blood diamonds. The cargo included millions of rounds of ammunition, rocket launchers, cannons, anti-aircraft guns, mortar bombs and anti-tank rockets.124 When the Angolan government discovered his duplicity Bout’s contracts were cancelled. This was one of the few times a client had taken umbrage at Bout supplying both sides in a conflict.

The Russian had been introduced to Liberia and its lax aircraft registration rules, which he used extensively, by Sanjivan Ruprah, Taylor’s lieutenant. A Kenyan national, Ruprah held mining interests in Kenya and was associated with a company, Branch Energy, which had diamond-mining rights in Sierra Leone.125 Initially Ruprah had introduced the Sierra Leonean government, the RUF’s opponents, to Executive Outcomes,126 a mercenary group constituted by former apartheid special forces and other assorted rogues.127 Executive Outcomes were highly effective after their entry into the war in 1995, forcing back the RUF’s advances and regaining control of a number of valuable diamond fields.128 Such were the fickle politics of the region that two years later Ruprah was working for Charles Taylor in sponsoring the RUF’s seizure of Sierra Leone. By November 1999, Ruprah had so integrated himself into the Taylor inner circle that he was appointed ‘Global Civil Aviation agent worldwide for the Liberian Civil Aviation Register’.129 In effect he was the boss of Liberia’s aeroplane registry, which Bout had already been using to conceal his arms-trading activities with considerable success. By 2000, Ruprah was directly involved with Bout in setting up front companies in Abidjan to effect arms deals. He had become Bout’s ‘business partner’.

By this time Bout was undertaking major deliveries for Taylor. He used a baffling array of front companies to do so, registering airline agencies such as San Air, Centrafrican Airlines and MoldTransavia in different countries around the world.130 In the case of Centrafrican, Bout used a corrupt official in the Central African Republic to get the plane registered without the government’s knowledge. In July and August 2000, one of Bout’s planes made four deliveries to Liberia from Europe. The Ilyushin-76 was first registered in Liberia in 1996 in the name of another of his companies, Air Cess. It was later deregistered in Liberia and re-registered in Swaziland until a survey by that country’s aviation authorities discovered major irregularities in the paperwork. It was again registered in the Central African Republic operating under the Centrafrican Airlines banner. Its call sign, painted onto the tail, had been fraudulently wrangled from a corrupt official without his government’s knowledge.131 In addition, the plane had dual registration, sometimes flying under the flag of Congo (Brazzaville). And when it was not making deliveries it was parked at Bout’s main business hub in Sharjah.132 When the shipment was about to be delivered it was transferred into the name of Abidjan Freight, a front company owned by Ruprah, before embarking on its journey on the multiregistered aircraft.133

This incredibly convoluted system was used to conceal not only the standard fare of rockets and ammunition, but also entire advanced weapons systems, which significantly enhanced the military potency of his clients. According to the UN: ‘The cargo included attack-capable helicopters, spare rotors, anti-tank and anti-aircraft systems, armoured vehicles, machine guns and almost a million rounds of ammunition.’134 Bout continued his arms deliveries into Liberia throughout the remainder of 2000 and into early 2001. Acting much like a legal defence contractor, he even provided after-sales support in the form of helicopter spares and rotor blades.

Many of the weapons provided by Bout and Minin were sourced in the Ukraine. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the Ukraine was left with one of the largest surpluses of weapons. As the country spiralled into economic crisis army officers in cahoots with the shadow dealers plundered these stocks. A parliamentary commission constituted to investigate allegations of illicit arms trading reached the sensational conclusion that Ukraine’s military stocks were worth $89bn in 1992 and that, in the course of the following six years, arms, equipment and military property worth $32bn were stolen, much of it resold. So explosive were the findings that the investigation was suddenly closed down, seventeen volumes of its work vanished and its members were cowed into silence. The MP who headed the inquiry, a former Deputy Defence Minister, Lieutenant General Oleksandr Ignatenko, was hauled before a court martial and stripped of his rank.135 Bout’s past military and political connections probably secured him access to this weapons trove, while Minin’s route was more likely through his organized-crime contacts.

But by late 2001 Bout faced increasing international obstacles to his deliveries to Liberia. Inspectors for the UN repeatedly named him and Ruprah in its investigations into the Liberia and Sierra Leone conflicts, recommending Bout be placed on international travel ban lists. But it was 9/11 that really upset the Russian’s plans. After the attacks, the US identified Bout as playing a role in arming the Taliban and he became one of the primary targets of the War on Terror. Making matters worse, Belgium issued a warrant for his arrest in 2002, claiming he had illegally hidden money flows of over $300m from tax authorities.136 Ruprah was arrested in Belgium in the same year, but later freed.137 Bout had to move fast. He uprooted himself from Africa and relocated to Russia, where he was protected by the state, which denied his presence in the country, despite regular sightings. While Bout had escaped justice, at least temporarily, Charles Taylor was now without the services of two of his favourite Eastern European arms dealers.

* * *

Taylor and the RUF turned to another, more infamous source, for weapons: Al Qaeda. Islamist operatives had been exploring diamond deals in Liberia and Sierra Leone since 1998, when the US sought to curtail the organization’s revenue streams following the bombings of US embassies in Kenya and Tanzania. In June of that year US investigators froze about $240m of Al Qaeda’s assets,138 a large portion of which was gold deposits held at the US Federal Reserve.139 Diamonds seemed a perfect source of income that was difficult to trace: small, valuable, highly mobile and difficult to detect. The traditional Islamic system of hawala, an informal network of money lenders that involves no paperwork and which exists throughout the Arab world, further aided Al Qaeda’s dual quest for monetary mobility and secrecy.140

Three months after the US seized the organization’s assets, a senior Al Qaeda operative, Abdullah Ahmed Abdullah, travelled to Liberia.141 Abdullah is suspected by US authorities of being the mastermind behind the US embassy attacks and was described by the FBI as a ‘top Bin Laden advisor’142 and the organization’s treasurer in Afghanistan and Pakistan.143 He was one of the original twenty-two members, and remains on the list of the FBI’s ‘Most Wanted Terrorists’.144 Abdullah had met the RUF’s General Ibrahim Bah in Libya, where Bah was being trained after working with the mujahideen in Afghanistan.145 Once in Liberia, Abdullah was introduced to the RUF leader, Sam ‘Mosquito’ Bockarie, to whom he handed over $100,000 in return for a small package of diamonds. He then met Charles Taylor and travelled to Foya aboard a Liberian helicopter, the same diamond centre to which Roger D’Onofrio had been taken years earlier.146

The RUF and Taylor expected Al Qaeda to follow up this initial meeting with a delivery of weapons. In March 1999, two Al Qaeda operatives, Ahmed Khalfan Ghailani and Fazul Abdullah Mohammed, went on a diamond-buying spree across the Central African Republic, the Democratic Republic of Congo and Angola before arriving in Liberia to see Taylor. To their immense embarrassment they hadn’t brought weapons for the Liberian leader. The relationship between Taylor and Al Qaeda faltered, at least for the moment.147 In December 2000, a few months after Minin’s arrest, the two Al Qaeda operatives returned to the country. At the Hotel Boulevard in Monrovia they met Ali Darwish and Samih Ossaily, who worked for a Lebanese diamond dealer, Aziz Nassour, who had operated widely in Africa and acted as ‘bagman’ for Zaire’s kleptocratic dictator, Mobutu Sese Seko.148 The four crossed into Sierra Leone and met the RUF for at least three days. Ossaily was there to negotiate on Nassour’s behalf and to take photographic evidence that the RUF could deliver diamonds. He was convinced of the RUF’s bona fides and entered into an agreement with the rebels, who agreed to sell huge quantities of diamonds to Nassour in return for weapons.149

By March 2001, the arrangement was operating at full steam. Ghailani and Mohammed returned to Liberia, from where they conducted diamond trades with the RUF for at least the next nine months. At first they lived at the Hotel Boulevard, which was both Sam ‘Mosquito’ Bockarie’s home-away-from-home and Samih Ossaily’s base. Mohammed was dispatched to the countryside to oversee the relationship with the RUF, while Ghailani remained in Monrovia. He was later moved to a safe house which had been leased by Aziz Nassour. Business was going so well that Nassour himself travelled to Liberia in July 2001 to implore Taylor to pull strings to double diamond production in Sierra Leone, a request accompanied by a $250,000 ‘donation’ to the President. Nassour had already made $1m in ‘donations’ to Taylor over the course of their relationship.150

Nassour also took personal responsibility to source the arms promised to Liberia in return for the diamonds. His first attempt was vigorous but unsuccessful. In December 2000, he approached Shimon Yelenik, a former Israeli army officer who was linked to the supply of weapons to Colombian paramilitaries151 and had worked as head of security for Mobutu Sese Seko, Nassour’s one-time employer.152 From his base in Panama Yelenik approached a Guatemalan arms firm which was represented by another Israeli, Ori Zoller, who had once served with the Israeli special forces. Zoller contacted the head of the Nicaraguan armed forces and received a list of available weapons and their pricing. Nassour then instructed his henchmen, Darwish and Ossaily, to brief the RUF. However, the deal did not go through. Ossaily claims to have had a sudden change of heart about his involvement and decided to tell all to the Belgian authorities while in Antwerp, the diamond centre of the world, to which he frequently travelled.153 No action was taken at the time by the Belgian authorities, but it halted the arms deal.

Nassour’s second attempt took place in May and July 2002. He paid for two shipments of weapons and ammunition which had been sourced from Bulgaria via a middleman in Paris, and passed through Nice before finally reaching Harper in Liberia. The first shipment was a massive 30 tons, and the second 15 tons of ammunition. Once it was offloaded in Liberia the ammunition was moved onto trucks and transported to Lofa County to be used against the biggest threat to Taylor’s presidency, the massed forces of Liberians United for Reconciliation and Democracy (LURD).154

Prior to Nassour’s second, successful arms deal, the entire operation was uncovered in a remarkable investigation by Doug Farah, the West Africa correspondent for the Washington Post. Using a senior source who was deeply embedded in the Liberian and Sierra Leonean networks, Farah unravelled the imbroglio and provided the information to American authorities.155 While US authorities, and the CIA in particular, were irked by a journalist stepping on their traditional turf, other countries took notice of the information. On 12 April 2002, Samih Ossaily was arrested in Belgium on suspicion of dealing in blood diamonds and was sentenced to three years in jail. At the same trial Nassour was found guilty in absentia, although his whereabouts remain unknown to this day.

* * *

Another source of weapons for Taylor during this time was Gus Kouwenhoven, a Dutch national, who like Leonid Minin mixed interests in logging with arms dealing. Heavy-set with a barrel-like chest and scruffy black hair, Kouwenhoven has a penchant for gold jewellery and distinctive gold-rimmed glasses that darken in bright light.

Born in Rotterdam,156 he made a name for himself as something of an international entrepreneur. In the early 1970s, after completing his military service, he went into business supplying tax-free cars for NATO personnel and later importing and exporting rice from South Asia. Through the 1970s he moved in the diplomatic set, was often spotted at high-profile parties, and frequented bars and clubs in downtown Amsterdam, where one bartender recalls him as ‘a flashy guy with the gift of the gab, fast cars and fast women’.157 Always a fixer – he was allegedly caught stealing petrol while in the military – his career as an international man about town was ended in Los Angeles when he was caught in an FBI sting trying to sell a stolen Rembrandt.158 He was released after just seventeen days but was deported from the US.

Kouwenhoven disappeared for a while, was in Sierra Leone in the late 1970s and surfaced in Liberia in the early 1980s. He quickly settled into the country, then run by President Samuel Doe, and married a Liberian woman, who bore him a number of children.159 His initial business in the country was the provision of luxury goods, in particular luxury cars. But his major investment was in Hotel Africa, a run-down 300-room hotel in the centre of Monrovia. He turned it around, opening a disco, the Barcadi Club, a restaurant, a pool and a casino.160 It became, in Kouwenhoven’s own words, the ‘oasis of Monrovia’.161 It was a major hub, the spot where the great and the good, both local and foreign, met to make deals and be seen. A former guard recalled that ‘every day there would be a parade of senators and ministers’.162 And it secured Kouwenhoven’s place at the heart of the Liberian elite.

In 1999, Kouwenhoven branched out from his life as a flashy hotelier, utilizing his now extensive government connections. In July 1999, the Oriental Timber Company (OTC) received a major concession for Liberian timber: roughly 1.6 million hectares, or 42 per cent of all of the country’s productive forests.163 OTC was majority-owned by the Hong Kong-based firm Global Star Holdings, itself a part of an Indonesian group of companies called Djan Djajanti. Kouwenhoven retained 30 per cent of the shares and was made the managing director of OTC and a sister company with considerable concessions, the Royal Timber Company.164 He was responsible for the day-to-day management of the companies and oversaw much of the $110m OTC invested in Charles Taylor’s Liberia. Operating largely from the port of Buchanan, OTC became a mini-government. It repaired a 108-mile stretch of road from Buchanan to inner Liberia, refurbished the port165 and even ran a private militia of security guards totalling nearly 2,500 armed soldiers.166

OTC was close to Taylor’s heart. He publicly referred to the company as his ‘pepper bush’, something of immense personal value.167 His concern for OTC’s well-being was because he received considerable money from its operations. In return for the concessions Kouwenhoven frequently made large payments to Taylor, which the Dutchman would later justify as ‘public relations’ expenses.168 It is unclear exactly how much Kouwenhoven transferred to Taylor but they were substantial amounts over and above an initial $5m payment in ‘advance taxes’.169 In an interview Kouwenhoven once admitted that he paid roughly 50 per cent of all his royalties from OTC to Taylor to fund his warmongering administration.170 It is likely that Taylor received not only ad-hoc payments, but was also made a shareholder in the company.171

OTC was important for reasons besides earning Taylor a decent income. In particular, the company’s refurbishment and control of Buchanan and its transport nodes gave Taylor another route to transfer arms into the country. Where Minin and Bout used air transport, OTC and Kouwenhoven relied on ships. According to a number of witnesses Kouwenhoven oversaw the importation of large quantities of weapons aboard a ship owned by OTC, the Antarctic Mariner, which was often used for logging exports.172 Witnesses recall that the ship docked a number of times between July 2001 and May 2002, and again between September 2002 and May 2003, disgorging huge quantities of weapons upon landing. Once unloaded, the AK-47s, RPGs and ammunition were transported by truck and jeep to Taylor’s presidential compound to be distributed among NPFL troops.173

Many of the shipments were organized via Abidjan Freight, a dummy company established by Sanjivan Ruprah. UN investigations revealed that Abidjan Freight was a useful cover for both Viktor Bout and Kouwenhoven, both of whom used the company to ‘conceal the exact routing and final destination of an aircraft delivering military goods to Monrovia’.174 Despite these attempts to hide their actions, OTC and Kouwenhoven were soon in the spotlight. Investigations by the UN and Global Witness began reporting on Kouwenhoven’s timber enterprises and his links to arms trafficking as early as December 2000. Soon after, much like Bout and Minin, he was placed on the official UN travel ban and had his assets frozen. But Kouwenhoven frequently broke the terms of his ban and was often seen visiting neighbouring countries. One trip to Holland was a journey too far and he was eventually arrested in his home town of Rotterdam.

* * *

By mid-2003 it was clear that Charles Taylor’s time was running out. Despite his control over large pockets of Liberia’s resources he was slowly losing ground to his opponents. One group, LURD, backed by Guinea,175 had been slowly advancing on Taylor’s territory since they first launched an anti-NPFL rebellion in 1999. Another group, known as the Movement for Democracy in Liberia (MODEL), had initiated its own rebellion with Ivorian support in 2003.176 Their blitzkrieg through Liberia devastated Taylor’s once iron grip on the country, only one third of which – Monrovia and its surrounds – he still controlled. The actions of the UN and international forces in disrupting the flow of arms to Taylor from the likes of Minin, Bout, Kouwenhoven and Nassour played a key role in weakening Taylor’s position.

In March 2003, the Special Court for Sierra Leone – a joint UN and Sierra Leone investigative tribunal – filed a sealed indictment against Taylor. By June 2003, its contents had been made public: Charles Taylor was to be arrested and face eleven charges of war crimes and crimes against humanity.177 If caught and found guilty he would spend the rest of his life in jail. It was not just his control over Liberia that was under threat, it was his liberty too.

Under these suffocating pressures Taylor initiated peace talks with his opponents. Over the course of an excruciating month a deal was hammered out. Once ratified in August 2003, the agreement stipulated that Liberia would be ruled by a transitional government until elections could take place in 2005. All parties agreed to the creation of a Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which would examine Liberia’s brutal past and grant amnesty to political criminals in return for disclosure of information.178 Under the terms of the agreement Charles Taylor would retain his liberty despite the indictments filed by the Special Court for Sierra Leone. In return for his promise to resign peacefully Taylor was granted political asylum in Nigeria by President Olusegun Obasanjo. He appeared on television to announce his resignation and his imminent relocation. Chillingly, he vowed: ‘God willing, I will return.’179

Taylor’s new home was in the illustrious Calabar area of Nigeria. Located in the south of the country, Calabar is a picture of tropical bliss, with the sea on one side and lush tropical forests on the other. Taylor and his entourage moved into a grand colonial mansion fronted by slim white columns on the prestigious Diamond Hill, virtually next door to the Old Residency, the mansion from which successive British Governors ruled Nigeria. And within a stone’s throw of the lodge where President Obasanjo resided when he was in the area.180

Taylor’s Calabar bolt-hole was supposed to be under lock and key. His mansion was located in a government zone and Nigerian security patrolled the perimeter of his property. Liberians, however, were convinced that he continued to influence their country’s politics. He certainly had the resources to do so. Of an estimated $685m earned during his presidency, Taylor had spent $70m to $80m on military operations every year, leaving between $150m and $200m at his disposal in exile.181 He also had ongoing investments in Liberia from which money was couriered to him in Nigeria by loyalists still operating in the Liberian government.182 He used his vast wealth to continually interfere with Liberia’s fragile transition. The Special Court for Sierra Leone claims that nearly half of the eighteen political parties which contested the 2005 elections were funded by Taylor, leading the UN Secretary General, Kofi Annan, to report to the UN Security Council that Taylor’s ‘former military commanders and business associates, as well as members of his political party, maintain regular contact with him and are planning to undermine the peace process’.183

Taylor’s continuing presence in Nigeria caused considerable consternation in international circles. The US, in particular, pushed hard for him to be returned to Liberia and face charges in Sierra Leone, a demand that was consistently rebuffed by Nigeria. In 2006, however, the newly installed President of Liberia, Ellen Johnson-Sirleaf, officially requested that Taylor be extradited from Nigeria to Liberia. Obasanjo, the Nigerian President who was rumoured to have benefited from Taylor’s generosity, reluctantly agreed and announced at the end of March 2006 that ‘the government of Liberia is free to take former President Taylor into its custody’.184

Taylor didn’t wait for the Liberians to act. In flowing white robes he fled his Calabar compound in a Jeep Cruiser displaying diplomatic plates, in which he had stashed money in a variety of currencies. He headed for Cameroon but was captured at the border town of Gamborou, nearly 600 miles from Calabar.185 Taylor has remained adamant that he had no desire to escape but was merely undertaking a trip to Chad about which he had informed Nigerian authorities.186 Regardless, he was arrested at the border and flown directly to Monrovia. From there he was taken aboard a helicopter to Freetown, where he was held in captivity.

During his violent six-year kleptocracy 60,000–80,000 Liberians were killed and countless more were brutalized, most traumatically the child soldiers who were forced to kill their parents and ordinary victims alike.187 Charles Taylor was undoubtedly the most brutal and venal of all the Merex operatives but the network was one in which he felt serenely comfortable.