The book has looked at awakening from several different perspectives, so there is quite a bit of material out on the table. This chapter reviews that material and tries to organize it more compactly as a working model that can account for both ordinary and awakened consciousness. My intention is to drive home, by expressing it in the contemporary language of cognitive and social science, the fundamental insight of all people who have experienced awakening: that awakened consciousness is a real, natural, and physical possibility for all human beings. The biological and cognitive potentials necessary for realizing it are there right now, built into all of us and waiting to be used. Without the perspective that awakened awareness provides, humans bumble along in a world of distortions and representations—of shadows, as Plato would say. It is my hope that science can help a little bit by making clear that awakened consciousness is just a different way of using the same human potentials that produce ordinary consciousness.

The Basic Model

Human consciousness is sometimes defined as awareness that we are experiencing awareness.

1 All noncomatose humans report having this experience, so it sets up a good goal for neuroscientists who want to understand how the brain produces consciousness. If the goal is to understand how and why the contents of consciousness vary, however, it is not very useful. To understand the similarities and differences between ordinary and awakened consciousness, we need a model that shows how both forms can exist in the same human body, even if only one is active at any given time.

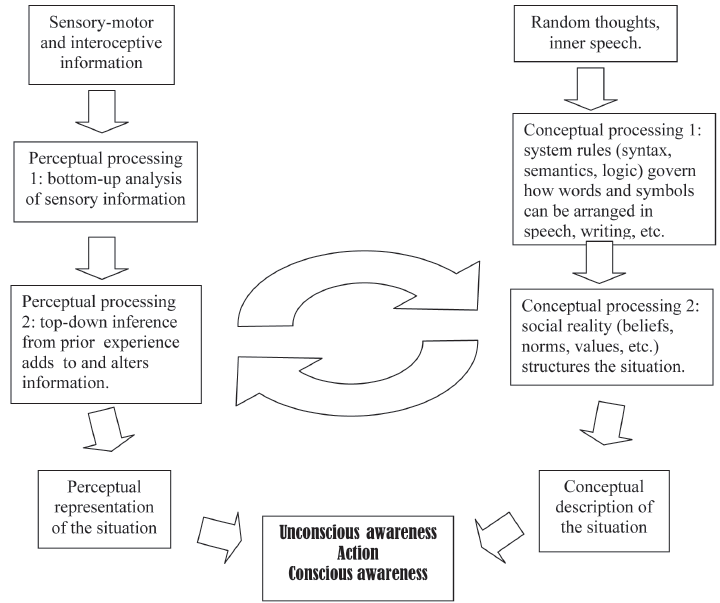

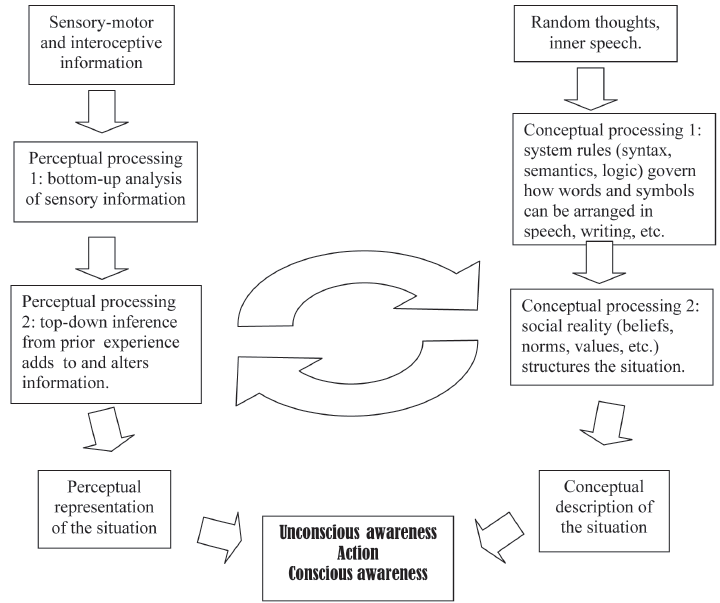

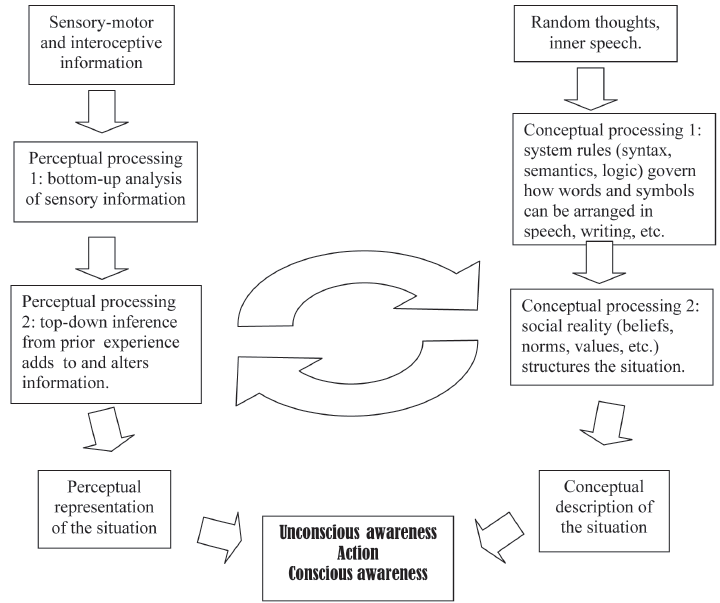

Figure 17.1 offers a brief summary of what I take to be general agreement on the basic factors involved in shaping the contents and quality of each moment of consciousness. If some parts of this model look a bit odd, it is because a few things had to be altered in order to include awakened consciousness.

2

FIGURE 17.1 The processes that produce awareness work to adjust and reconcile perceptual and conceptual representations.

The model begins by assuming that awareness is shaped by both perception and conception, where perception works with external and internal sensory information and conception works with symbols (especially language). In

figure 17.1, perceptual processing I follows rules that analyze sensory inputs and shape them into the percepts or perceptual representations that appear in awareness. Conceptual processing I also follows rules, which in this case arrange words (or other symbols) into the sentences that we hear as inner speech. Perceptual and conceptual processing usually go on at the same time, and they interact. As thousands of priming experiments show, while perceptual processing is busy identifying percepts, words that are associated with the percepts are activated and organized. So perception and conception affect each other, even at this early stage.

But bottom-up processing, as this is called, is only the first step toward producing what will appear in awareness. Sensory information is often incomplete, as when one figure in an image is partly obscured by another. Perceptual processing II tries to fill in the missing information by generating completed percepts that are consistent with previous experience (top-down processing). Sometimes this “guessing” can create optical illusions (i.e., errors), but most of the time it is useful.

3 Conceptual processing II works in the same way but even more powerfully, by trying to make both percepts and words consistent with previous experience (especially with the beliefs, norms, customs, and values of social reality). For example, when shown a picture of a multiracial situation on a bus in which a man (who is white) holds a knife in his hand, many respondents later put the knife in the hand of a black man. Eyewitness reports from people who all see the same live incident vary in the same way—awareness is shaped by what we expect to see.

As a result, while we can think hypothetically about perceptual processing producing a “pure” perceptual representation of a situation or conceptual processing producing an “accurate” description of the situation, in fact the two usually interact and are shaped by previous experience all along the way. And as W. I. Thomas pointed out almost a hundred years ago, when we define a situation a certain way, it is real in its consequences.

4 We are perceiving, conceiving, and translating back and forth between the two continuously. Chomsky refers to this as mental activity across two interfaces, the sensory-motor interface and the conceptual-intentional interface.

5Before applying the model to ordinary and awakened consciousness specifically, three of its properties should be highlighted. First, the processing it describes is generative, continuously producing fresh versions of awareness from available materials. Second, both perceptual and symbolic processing attempt to maintain consistency among previous experience, incoming sensory information, and conceptual systems like social reality. Third, almost all of the processing shown in

figure 17.1 is unconscious. Usually, as the research stemming from Libet’s work has shown, unconscious awareness is generated first; it is expressed very quickly in action, and only an instant or so later experienced in conscious awareness. So in the model of consciousness used here, almost everything that goes on is unconscious. That doesn’t make conscious awareness unimportant, but relations between the two kinds of awareness deserve a little more discussion.

The prototype example of unconscious awareness is blindsight, in which people who are not consciously aware of seeing anything nevertheless show by their actions that their brains have carried visual processing to the point where it works perfectly for guiding action but does not enter conscious awareness, due to trauma.

6 I don’t know what the experience of blindsight feels like, but I assume that these people are aware that they are aware because their proprioceptive senses tell them that they have successfully navigated. They are probably also relieved to find out, conceptually, just what causes their condition. This conceptual information would affect their conscious awareness of what they are doing and how they live. The important point is that unconscious perceptual awareness, with or without conscious conceptual awareness, qualifies as a form of consciousness. Animals seem to get by quite well with little or no conceptual awareness, so the argument can be made that animals qualify for consciousness on the basis of unconscious awareness alone. For most of our waking hours we humans could probably also get along just fine in the same way.

Now to apply the model to how ordinary and awakened consciousness operate to carry out important mental functions.

Generating Ordinary and Awakened Awareness

Ordinary conscious awareness is generated when a perceptual representation is modified to be consistent with the conceptual system. In the case of language, the processing also tries to organize representations into a coherent narrative, a story that is consistent with the person’s social reality, explains what is going on in a situation, and prescribes behavior. Often the story features adventures of the social self in a world defined by social reality. It has a past that the person can enjoy or resent and a future to plan for or worry about. Unconscious processing will try to generate a story that favors the self and is faithful to the person’s social reality, even if that requires distorting the immediate situation as represented perceptually.

Carrying out all this symbolic processing requires considerable effort, and that is over and above the processing necessary to generate the initial perceptual representation. In psychology the concept “cognitive load”

7 posits limits on how much processing the brain can engage in at any given time. It seems likely that as the effort devoted to conceptual processing increases, the amount of activity available for perceptual processing will diminish. This would explain the experience, often reported by meditators (see

chapter 13), that as their minds become quieter the world around them becomes brighter and more vivid. The implication is that without the burden of symbolic processing (especially the chattering of inner speech that goes on continuously), our conscious awareness of perceptual representations will seem clearer and more vivid.

So far, then, we have two important ways conceptual processing can modify a perceptual representation. First, it can alter the contents and structure of perception to better fit the contents and structure of the symbol system (especially as symbolic information becomes reified into social reality and the self). Second, due to the additional processing demands, it can make the perceptual image available in conscious awareness appear somewhat washed out, less vivid.

There may be a third effect, however, which involves the property of awakening identified in

chapter 13 as no separation. As a three-dimensional perceptual image is translated into words to form the linear, one-dimensional sentences of a story, awareness almost necessarily narrows to focus on the actor as protagonist.

8 The remaining dimension, time, is forced to express events from what Austin calls an egocentric perspective,

9 which then becomes the natural way to organize awareness. Through the ages, people have tried to make up for this limitation of egocentric awareness by finding ways to experience action as an organic part of a group rather than as a separated individual. The examples I can think of are nonverbal and involve closely interacting ensembles, such as jazz groups, basketball teams, and improvisational theater groups doing Grotowski exercises.

My argument is that these three features of ordinary awareness occur especially when conceptual processing imposes language on perceptual representations. The task now is to account for why these features do not occur in awakened awareness. A good way to start is to consider some examples identified earlier in which, because the creature in question shows no indication of possessing language, it seems likely that no symbolic processing takes place.

First, animals. Given that all known animal communication systems are severely limited compared with human language, it seems likely that animals operate solely on the basis of perceptual representations

10 (see

chapter 14). Of course, we don’t really know what their awareness is like because they can’t tell us.

Second, babies. As we saw in

chapter 15, they show many of the behaviors associated with awakened consciousness. The reasonable assumption is that conceptual processing begins as infants learn to talk; prior to this, babies’ awareness must depend on perceptual representations.

11 As the behavior of babies is studied more and more closely, the findings suggest that evidence of awakened consciousness gradually disappears as the child learns language.

12Third, the case of Jill Bolte Taylor. A stroke that temporarily eliminated all language processing left her able to function on the basis of perceptual processing. After she regained language capabilities, her descriptions of the awareness she experienced during the stroke were remarkably similar to the descriptions of awakening studied in

chapter 13.

In all three cases, since language does not exist, there is the possibility that “pure” perceptual representations, unmodified by symbolic processing, provide the contents for awareness. What about adult humans, for example, those interviewed for this book, who have worked to quiet their minds of inner speaking

13 and let go of attachments to symbolic representations? These people have not lost the ability to speak or comprehend language, and they have intact working memories with extensive stores of symbolically represented information. There is no physical reason their awareness would be restricted to perceptual representations. So what exactly is the role of language and conceptual processing in their awareness?

To explore this question, consider the following comments by Jack Kornfield: he gives a beautiful description of perceptual reality, beginning with its pervasive silence:

It is not that there are never any thoughts, but for the most part it becomes really silent. It is like going from the windswept, weather-filled atmosphere, getting to the surface of the ocean and then dropping down below the level of the water, like a scuba diver, into a completely silent and different dimension. While there are some reflections that might go by, it is a completely different state of consciousness. . . . Whatever you call it, there is something in the psyche, in the greater consciousness, that knows these states and this terrain. And when the mind is deeply concentrated and open, and resolutions are made, magic happens. And of course, this can lead to the highest magic of all, as the Buddha said, the magic of the wisdom that liberates the heart.

14

I interpret this quote to say that silencing the mind of inner speaking allows one to settle into a conscious awareness of the moment that is informed only by perceptual representations. When this is achieved, magic happens: awareness changes drastically. However, there can still be some contact with language—Kornfield notes that “some reflections” may go by. I take this to mean that unconscious processing continues during awakening and may involve symbols. The purest instance I know of personally occurred roughly ten seconds into my major awakening experience. A voice in my mind (my voice) said, “So this is what they mean by nothingness—no social reality.” The voice was not quite accurate—I still knew all about social reality, but the reification and attachment had vanished.

15 In spite of the slight misstatement, however, this was a valuable insight that had never before occurred to me. As the experience went on, additional inner comments arose occasionally, but mostly all was quiet.

Therefore, I conclude that awakened awareness has its base in perceptual reality. Subjectively, perceptual experience with no conceptual activity going on in conscious awareness feels like the world just the way it is, nothing added. Symbolically coded information is available, but social reality and the social self are viewed objectively, almost dispassionately.

Earlier I proposed three ways conceptual processing alters perceptual representations during ordinary awareness. Now we have their opposites, three ways in which, during awakened awareness, perceptual reality is protected from the effects of conceptual processing. First, perceptual representations are not altered to fit social reality, because without reification there is no latent feeling that social reality and the symbolically represented self are “true.”

16 Second, the vivid image quality of pure perceptual awareness is no longer diluted by the cognitive load required for conceptual processing. Third, because three-dimensional perceptual reality is not translated into one-dimensional language, the allocentric perspective can continue to dominate over an egocentric perspective. The world is organized just the way human perceptual processing presents it, with no dramatic storylines and no self to struggle through them.

If my conclusion is correct, then we have some interesting questions for neuroscience research to investigate. If the brain is switching between neural systems, what are those systems and how do they work? The differences between ordinary and awakened awareness proposed here fit nicely with Austin’s distinction between egocentric and allocentric neural systems, so his work provides important suggestions for research. In particular, he identifies a dorsal cortical system as being responsible for egocentric processing and a ventral system for allocentric processing.

17 He points to research on the default network

18 as being heavily implicated with self, and suggests that specific nuclei of the thalamus play a key role in allowing a switch from egocentric to allocentric processing. All that is left is determining exactly what the de-reification network is and how it works. Somehow things happen, probably in the brain, that allow one to sit (stand, walk, live one’s life) with an awareness firmly, peacefully, and silently based on pure perceptual reality. Then everything is just deliciously the way it is, and one feels no more important than any other thing or person.

Emotions and Feelings

There are hundreds, probably thousands, of words available to denote the various emotions experienced in ordinary consciousness. But what about awakened consciousness? Did the Buddha experience emotional states other than equanimity and compassion? In the most serious effort I know of to uncover Gautama as a flesh-and-blood person, Stephen Batchelor concludes that he certainly knew about, and had to deal with in himself, a wide range of familiar emotions.

19 Being familiar with them doesn’t mean being at their mercy, of course, so the project now is to understand the role of emotions and feelings in ordinary and awakened consciousness.

First, some definitions. Damasio and Carvalho identify emotions with action sequences that our bodies engage in and our minds think about.

20 Emotions are thus cued by our perceived relationship with the external environment, while feelings are interoceptive experiences that tell us what is going on in our bodies.

21 Extending this definition to ordinary consciousness, emotions are usually triggered by stories or scripts activated by the conceptual system to frame our awareness of the moment. Socially appropriate emotions are coded into the story. We learn both the basic story-line and the emotional reactions that are expected to accompany it during childhood, so most of the time we react the way we have been programmed to react when we encounter (or think about) a situation that fits the operative storyline. Social reality therefore plays a large role in emotion, and to a considerable extent, during ordinary consciousness we experience emotionally what the drama generated by our conceptual system tells us we should experience.

Then what about awakened consciousness? If the contents of social reality are viewed objectively, not from the perspective of the social self as a subject in that reality, the experience might be compared with playing a role in a play but knowing that it is just pretend. Without reification, we have removed the linchpin that connects situations and action sequences with emotional responses. Without a social self struggling along in the storyline provided by social reality, whatever happens in a situation happens, and that is just the way the world is. But this takes us back to the previous question. If letting go of the perspective of the self living in social reality is the essence of awakening and emotions are no longer triggered by the script being followed, what can be said about feelings?

One way to answer is to return to the discussion of animals in

chapter 14. Whether animals experience what we call emotions is controversial, but there seems to be general agreement that even quite primitive species possess a basic core of feelings. These certainly survive in humans, so we can use them to narrow the question: Do people react emotionally during awakened consciousness in the same way they do during ordinary consciousness to situations associated with fleeing, fighting, feeding, or sex? Maybe there is not so much difference. If danger threatens, why not flee? If someone attacks a child, why not try to fight the attacker off? If awakened people go without eating for some time, they presumably experience hunger just as ordinary people do. And as for sex, the lesson of

chapter 13 was that awakened people can certainly experience arousal.

22 Whether these immediate reactions should be called emotions or feelings is of course an open question. But it seems that awakened consciousness does not react with the full repertoire of emotions to the scripts that add drama to a situation.

Thinking

Chapter 14 argued that what eventually separated humans from other animals during the course of evolution was an improved capacity to make available during unconscious processing percepts and symbols that refer to phenomena not present in the immediate situation. Early

Homo species used this capacity to invent language and to include both percepts and symbols in the processing leading to unconscious awareness—that is, to do what we call thinking. So the question to be addressed now is, What is thinking like in ordinary and in awakened consciousness?

Holding the contents of conscious awareness steady for even a moment (“paying attention” to the contents of awareness) introduces feedback in which the contents of consciousness become sensory and conceptual input for a new cycle of processing and awareness. The brain examines the contents of conscious awareness and, following its normal course of activity, generates new awareness and action (see

figure 17.1). The contents of conscious awareness thus become part of the information that unconscious processing processes, rather like looking in a mirror. This ability to respond to conscious awareness as new input allows the unconscious part of the brain to talk to itself. It also allows us to meditate, by keeping our attention focused on perceptual rather than conceptual awareness. And especially, it makes possible the achievement of which our species is most proud—reflective thinking.

In order to use conscious awareness effectively, we therefore need to draw on and develop further our capacity for attention, which allows us to control the contents of conscious awareness. For example, we can direct the focus of our attention by zooming in or out on current perceptual inputs, by emphasizing verbal thoughts rather than percepts (or vice versa), by letting memories or new thoughts be inserted into the display or blocking them out. We can allow free association in response to the display or require a tight focus on following familiar logical steps to solve a problem. These dynamics show up very clearly in Daniel Kahneman’s masterful Thinking Fast and Slow.

Kahneman uses the term “fast thinking” to refer to cases in which unconscious processing responds to a situation by acting on it immediately and conscious awareness simply shows the resulting thought or action.

23 The decision may involve language, as when we say something spontaneously without pausing for a moment to reflect on it (to “think before we speak”). What we say may be brilliant and perfectly appropriate, or embarrassingly stupid—fast thinking can go either way. Fast thinking works better when attention is focused on the moment and our minds are free of distractions, as when Olympic athletes visualize their routine before beginning their actual event. When attention is focused and distracting thoughts are no longer present, optimal action is possible. At this level, fast thinking can approximate the third property of awakened consciousness, “not knowing,” as discussed in

chapter 13.

24Kahneman’s “slow thinking” takes place when unconscious processing responds to a situation but attention delays action until the recommended action is displayed, examined, and perhaps resubmitted for further processing and new suggestions. Slow thinking imposes a time-out to look for better information or try different procedures, perhaps using rules of logic or math to do some additional calculations and projections.

25 In that mode we can perform many kinds of mental experiments. The important point is that a feedback loop is under way, as a conversation between unconscious processing and conscious awareness (or better, as the reaction of unconscious processing to the reflection it gets from conscious awareness). If examination of that reflection suggests that it might be a good idea to think about it a bit more carefully, then unconscious processing can respond with new contributions, which can in turn be examined. So slow thinking uses unconscious processing to propose solutions and decisions, awareness monitors the thought process and provides reflection, and attention shuts out distractions and maintains the integrity of the display.

From this a major question emerges: Is slow thinking possible while in a state of awakened consciousness? I propose, as hypothesis, that it is not, that awakened consciousness is restricted to fast thinking. The interviews did not go far enough to say much about this, so I am relying on my own experience here. When I am in a mental state that approximates awakened consciousness and I try to think about something carefully, using slow thinking, I quickly find myself switched back into ordinary consciousness. That happens every time I sit down to work on this book. The slow thinking goes well, but returning to awakened consciousness requires concentration and may take a while, depending on how long and how deeply I have been doing the slow thinking. Someone more advanced than I who is firmly rooted in awakened consciousness may be able to do slow thinking without losing his or her grounding in perceptual reality. I hope to pursue this matter further in future research.

By way of summary, I can state the obvious: both fast and slow thinking work better when a high level of attention is maintained,

26 and both are driven by unconscious processing, which never rests. But unless it is controlled by attention, unconscious processing may use its reflection in conscious awareness to carry on more or less random conversations with itself. This is the kind of thing Buddhists call “monkey mind,” but to stay within Kahneman’s framework I will call it “wandering thinking.”

27 Inner conversations can be constructive, and certainly entertaining, but overindulgence in wandering thinking means that conceptual processing strongly dominates perceptual processing. This also means that ordinary awareness is firmly in control.

Meaning

Chapter 16 explored the ancient and modern versions of

dukkha theory, as exemplified in the thinking of Gautama and Giddens. Life in ordinary consciousness means living within the carapace of symbolic reality, and

dukkha theory says this experience ranges from dissatisfaction to suffering because ordinary consciousness is inescapably and by definition out of touch with the essence of perceptual reality. First, ordinary awareness must at each moment construct a representation of the world that reconciles social reality with perception. This often requires changing either what our perceptual systems tell us or the definition of the situation that our social reality asserts. If the gap cannot be bridged, the contradictions can be distressing. Second, ordinary consciousness must avoid ambiguity by providing satisfactory explanations why that situation is happening.

28 Both kinds of problems are amplified due to rampant social change and the positive value that social reality now gives to questioning itself.

In both cases, the effect of cracks opening up between perceptual reality and symbolic reality has been to threaten the ability of social reality to provide meaning for life. Efforts to reestablish or rediscover meaning have taken three forms: change social reality so that it better fits what we perceive; cling more strongly to traditional versions of social reality (if necessary, denying the validity of what perceptual experience presents as “facts”); and shore up the social support that makes social reality work. We see all three responses frequently in the world today.

What was only partly discussed in

chapter 16, however, is the question of what provides meaning in awakened consciousness. Awakened consciousness is not emotionally concerned about whether the conceptual explanations provided by social reality are satisfying or distressing, because its base is in perceptual reality and scripts generated by social reality are not reified. Instead, meaning is provided by the

feelings that accompany perceptual experience. Meaning in perceptual reality depends on how the current moment feels, not how its contents are compared with things past, future, or imagined. These feelings (according to Damasio) originate in the brain stem. They come from interoceptive sensory inputs and tell us whether our body is (or is not) all right. I am extending this idea to explain why, in an awakened state, I feel connected in a solid and authentic way with the world around me. Then the world feels good and kind even if bad things are happening at the moment. Those feelings fill life with meaning, so

dukkha is not a problem. Pat Enkyo O’Hara talks about this as variations on a theme of joy:

When we think of joy, we think of a buoyant, upward-moving feeling of delight, pleasure, and appreciation. We may associate joy with happy things, with falling in love, or with getting what we want. But actually there is a deeper, more resonant, soulful feeling: the joy of life no matter what the circumstances are. . . . This quality of joy hangs around the edges, allowing you to open yourself to being awake and new with each experience you encounter.

29

The gulf between meaning provided by the conceptual structures of social reality and meaning provided by this kind of feeling is total, and crossing it can be traumatic for someone on the path to awakening. Several people have told me that at some point they would start feeling rather deep shots of anxiety and find themselves pulling back rather than trying to live mindfully. Letting go of the familiar, ordinary form of meaning and allowing oneself to slide into the other can be a perilous adventure the first time it happens.

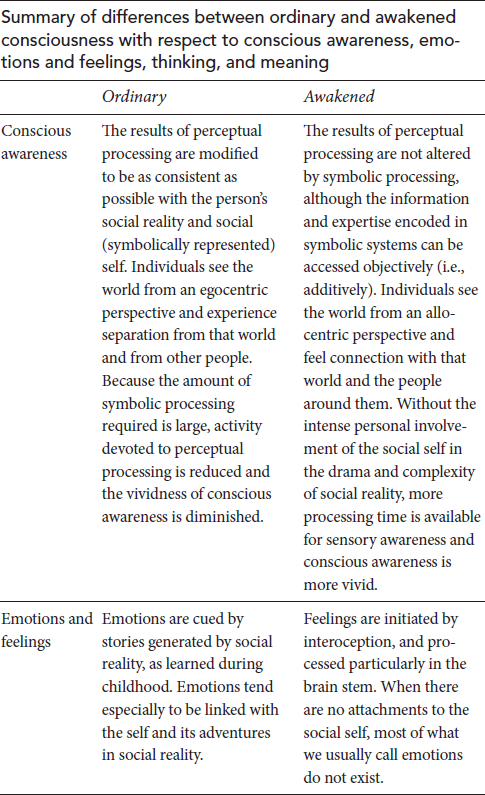

TABLE 17.1

The question, What is awakening? can now be answered by summarizing each concept as it finds expression in and for ordinary consciousness.

Each row of the table identifies four essential differences between ordinary and awakened consciousness, and for a typical human being living in ordinary consciousness, identifies the changes that must take place in order to move to awakened consciousness. These can be compared with the training practices described by the teachers in their interviews and summarized in

chapter 12. For example, to move from ordinary to awakened conscious awareness, one must improve one’s capacity for living in perceptual reality by using attention to focus conscious awareness on immediate experience while letting go of conditioned responses to social reality. To move from the emotions of ordinary consciousness to the feelings of awakened consciousness, one must learn to see reactions linked with the social self for what they are (that is, de-reify the self) and focus instead on what the body is feeling. In Kahneman’s terms, the cognitive style operative during awakened consciousness is fast thinking. To further develop this capacity, the primary task is to move attention to perceptual reality and away from wandering thinking. Finally, one must learn to accept the source of meaning that is available in perceptual reality while letting go of the emphasis ordinary consciousness places on conceptual or narrative meaning.

Research Implications

The table can also be used to identify promising areas of research. Some are general and some apply to specific topics.

Chapter 13 derived from the interviews three properties that describe the way awakened awareness is experienced subjectively. Eleven teachers is a small sample, so one obvious research improvement would be to interview more people. Second, the interviews presented in this book were exploratory because I had no idea where they were going to go. Now that there are some preliminary results to work with, a more structured design would be appropriate. For example, the interviewer could guide the interview to make sure that key topics are addressed and probe to elicit finer-grained details. These extensions of the present research apply at the level of the mind, and I hope to begin working on this approach soon.

General implications at the level of the brain. For neuroscientists, the big challenge has been proposed by James Austin.

30 His theory of egocentric and allocentric processing systems seems (to this non-neuroscientist) to identify in detail various areas of the brain that participate in each system. One problem, of course, is that it is not easy to find people who appear to have experienced awakening and interview them, and it will be even more difficult to get them to spend time in an fMRI machine. Not impossible, however—there have already been several brain scan studies of long-term meditators, and some of them must have experienced awakening.

31 Most research has focused on attention, which is important but leaves other brain activities untouched. It may be possible to find out who these meditators are, then ask them to describe their experiences, use this to estimate approximate degree of awakening, and then compare data across categories. So far this does not appear to have been done.

32

Conscious awareness. Theoretically, conscious awakened awareness is an unaltered

33 version of perceptual reality (with conceptual information available but not reified), while in conscious ordinary awareness the contents of perceptual awareness will have been modified or rearranged to better fit social reality. The key difference is reification, which presently is a mental term. Studying reification (and its opposite, the de-reification that occurs as part of awakening) at the level of the brain may be more accessible than it first appears. Research on distributed association networks suggests that these densely interconnected networks, which widely span discontinuous areas of cortex, are capable of producing sudden shifts in awareness similar to reification-dereification.

34 For example, the “default mode network”

35 appears implicated in shifts from goal-oriented to passively attentive states of awareness.

36 This is a different sort of shift, but the findings indicate that major shifts in subjective experience may be linked with measurable brain activity.

Emotions and feelings. The hypothesis is that in ordinary consciousness emotions are cued by symbolic reality, and particularly by the adventures of the social self in situations scripted by social reality. Escaping from this emotional attachment to the social self has been considered, from the teachings of Gautama onward, to be the most important characteristic of awakened consciousness. Research on this topic is therefore both extremely important and very difficult. At the level of mind I see no alternative to simply asking people to describe their subjective experience, although laboratory research might be designed to study emotional responses before and after experiencing awakening. We probably must wait for neuroscience to resolve the hypothesis by identifying the mechanisms that allow selflessness to become operative in the allocentric system.

37

Thinking. My experience has been that slow thinking is incompatible with awakened consciousness, and my hypothesis therefore is that the brain is organized in such a way that awakened consciousness only allows conscious awareness of percepts or symbols that are immediately present. Slow thinking requires holding in conscious awareness percepts or symbols that do not refer to anything immediate, so of necessity, slow thinking must take place in brain areas that handle ordinary consciousness. What also seems true from my experience is that slow thinking activates other components of ordinary consciousness. As a result, if I do some, I must use conscious attention to switch back once the slow thinking is completed.

I look forward to continuing the research begun here and asking more people to describe their day-to-day experience of living with awakened consciousness. Personally, since writing this book has required a great amount of slow thinking, returning to some semblance of awakened awareness usually requires at least a short period of meditation to quiet my mind. It’s easy to imagine that for people more deeply and firmly centered in awakened consciousness the transition back to that state after some serious slow thinking is simple and automatic. Or perhaps people who have developed their capacity for awakened consciousness more fully are able to engage in slow thinking without being pulled back into ordinary consciousness, so that slow thinking is available as a useful tool but does not compete with awakened consciousness.

For now I am sticking with the hypothesis that the brain systems that handle slow thinking are separate from those that generate perceptual awareness. Neuroscience research on this may not be so difficult. It is known that different areas of the brain are active during perceptual processing and language processing. The next step would be to find areas differentiated for fast thinking and slow thinking (brain areas for wandering thinking have already been identified). Once this is done, brain scan research on awakened subjects should be able to determine what is going on in other areas during and after a period of slow thinking. But attention is important, not only in switching from one mode to the other but also in allowing each mode to operate efficiently when it is active.

38Meaning. Meaning is something we feel, subjectively, so the question is, What provides or supports this feeling? The answer proposed here is that in ordinary consciousness, meaning is experienced when one’s symbolic reality provides coherent explanations for the events of life and is supported by the social group. Meaning in awakened consciousness, in contrast, comes when one’s body provides primordial feelings of being whole, connected, and in tune with the world.

Dukkha theory says that the problem of meaning in ordinary consciousness can never be fully solved. Since ordinary awareness is necessarily a symbolically represented version of awakened awareness, some kind or degree of suffering, dissatisfaction, or feeling out of touch with life always lurks in the shadows.

I’m not sure what neuroscience can do with dukkha, but research at the level of the mind can proceed using either self-reports or observed behavior. What people tell you about their state of dukkha may not be trustworthy—most would probably respond like the young Ajahn Amaro when a Buddhist monk told him that life is suffering: “No, that’s not right; I’m fine, I’m not suffering” (he added, in his interview, that he was big on denial in those days). Dukkha is one of those ailments that you may not know you have until you are free of it. But sensitive and carefully designed interviews could provide useful information.

Another methodology for research on

dukkha theory involves studying responses to social change, as changes in religious affiliation were studied in

chapter 16. Many of the problems that have plagued human existence on this planet stem from attempts to find relief from the itch or pain of

dukkha by developing and clinging to one of the almost infinite versions of social reality our species has come up with over time. Many databases containing useful information on attitudinal and behavioral responses to social change are available for statistical analysis.

Scientists and Buddhist scholars of all kinds will doubtless come up with better research strategies than those suggested here, not to mention improvements in the theory they are designed to address. If the present suggestions help further the scientific study of awakening, then this book will have made its contribution.

Concluding Notes

Through the centuries, awakening has been held out as a beautiful jewel, available for all people to enjoy. Starting with and including Gautama, those who have experienced awakening have wanted to share it, as something that is wonderful and possible. If this book helps make the message relevant to the Western world, that would be personally gratifying. The problem, though, is that helping others experience awakening is not easy, as the past two and a half millennia demonstrate. Nevertheless, if humans are going to stop messing up this planet, we have to find a way to reawaken this potential. In this spirit, I can think of no better way to conclude than by looking carefully and realistically at conditions in the world today that encourage or impede the spread of awakening.

First, in the West at least, Buddhism and other paths to awakening are presently attracting people who come almost entirely from highly educated, relatively well-to-do backgrounds. People who don’t know whether they will have a decently paying job next month, or food and shelter for their children, are suffering from physical

dukkha, not the fancier kind that leads materially comfortable people to become interested in awakening. Working to eliminate the conditions that impose material deprivation on so many people is therefore crucially important if the potential for awakening is to be available to all. Underdeveloped nations need continued economic development, along with improvements in the social and health conditions that support it.

39 But developed nations have their own problems, and in the United States things may be getting worse. There are steadily increasing inequalities of income, wealth, and education; if these trends continue, more and more people will be trapped at levels where material problems overshadow the possibilities of awakening. One important way to help spread the promise of awakening to all people is therefore by working to overcome inequality.

The second set of conditions is positive. Among the large numbers of people who

are financially comfortable, there appears to be a lot of searching and experimenting going on with respect to values and lifestyle choices. Much of this is certainly encouraged by the institutionalization of questioning discussed in

chapter 16, and the accelerating rate of social change that goes with it. There is an interesting coincidence between the values and activities that prepare one for awakening and those that social research has shown encourage happiness (e.g., helping others, spending time in wilderness, meditating). Everyone likes happiness, but as the research makes clear, we are often confused about what will make us happy. There is an important convergence between the research findings on what really contributes to full happiness and the long traditions of spiritual and philosophical wisdom about true happiness. As more people become aware of and influenced by this convergence, the pool of those who might become interested in awakening grows.

One limitation, however, is that most of these lifestyle and value changes involve leisure, not work. People in a wide variety of jobs and professions report experiencing high levels of on-the-job stress, to the point where they have to leave their careers to enjoy happiness or pursue awakening. That should not be necessary. It should be possible to structure the world of work to be at least compatible with awakening, and a large literature of organization theory and practice suggests ways it can be done. I don’t want to sound utopian—a corporation whose happy employees are pursuing awakening while they work sounds very nice, but if it is not done right, a company could easily lose money and have to go out of business. The point is that in order for the world to change in a positive direction, we need to balance changes in living patterns that encourage happiness and awakening with the need for efficient production. Someone had to grow the rice that Buddhist monks gather in their bowls during their rounds of begging.

Being a numbers person, I was impressed by the announcement of the King of Bhutan in 1972 that his country would begin paying attention to both Gross National Product and Gross National Happiness. If we had measures of GNH as well as GNP visible in the news, we could see how we are doing relative to other nations and be reminded to pay attention to both happiness and production. That would be a step in the right direction, but like many steps in a new direction, it immediately opens up another problem.

Chapter 13 concluded, after careful consideration, that awakening does not have to include compassion (conversely, we know from the many examples of compassion in the world that compassion does not require awakening). Compassion, it appears, must be cultivated for its own sake. A nation without the qualities of compassion would be a sad place to live, so perhaps we also need a measure of Gross National Kindness. A world whose nations are trying to rank high on all three measures, while not necessarily perfect, would be an amazing improvement.