CHAPTER 7

A Wonderful Thing to Save: How Communities Can Unite to Preserve Brainpower

Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world; indeed, it’s the only thing that ever has.

—MARGARET MEAD

Even without significant wealth or political clout, communities of color acting jointly have begun to transform the environment and health of marginalized people assailed by invisible poisoning. Consider that the first sweeping demands for environmental justice were ignited by groups like the middle-class residents of nondescript Afton, in North Carolina.

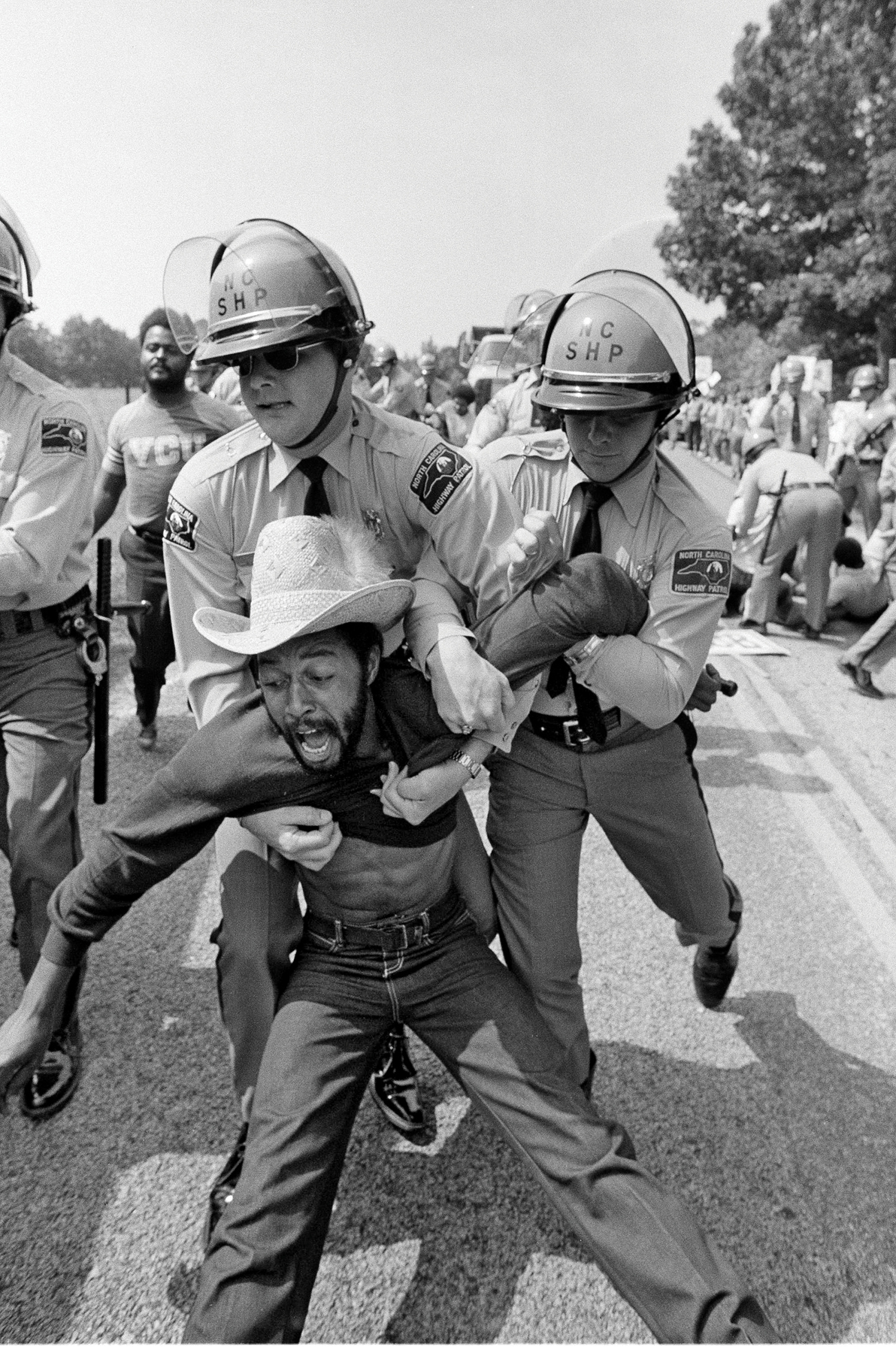

On a hot day in mid-August, throngs of North Carolinians from this predominately African American town and surrounding Warren County hoisted signs and banners as they chanted and sang stanzas of “Ain’t no stopping us now,” “We shall not be moved,” and other familiar hymns of the civil rights movement. White supporters brandishing signs and fists swelled their ranks, and formations of chanting neighborhood children filled the roads, hoisting placards and banners.

The marchers had gathered to defy a state convoy of trucks. As the protesters vowed to halt the vehicles’ incursion, armed helmeted police responded by aiming weapons as the sheriff took up his microphone to invoke law and order.

He warned that if they did not disperse, the assembly would be arrested. As the first resister was dragged, passively limp, into a police van, others lay in front of the trucks. As they were cuffed and led away, one by one, the chants and songs continued into the night.

The placards, the shouted demands, the playlist of venerated civil-rights hymns, the armed police, and the arrests presented a drama familiar to Americans. Throughout the 1960s, we absorbed such spectacles nightly with our dinners on the six o’clock news.

Not only the human-rights passion play but also the demographics were those of an iconic Southern civil rights protest, in which the black and disenfranchised ascended a moral high ground in the face of state force.

Police drag a passive Afton, North Carolina, protester to jail. (AP Photo/Steve Helber)

Seven of every ten Warren County citizens are black, and one of every five is poor, but although most residents were middle-class, they wielded little political power. However, thanks to their collective action, Afton’s protests assumed a grander scale than most. National television cameras transmitted a seemingly endless stream of protesters and arrests that continued for six weeks. During that time, 550 people were arrested, giving rise to what the Duke Chronicle called the largest Southern civil disobedience since Martin Luther King Jr. had marched through Alabama.

Birth of a Movement

But Dr. King was long dead. The Afton protests took place not in 1965, but in 1982, and the participants were not resisting voting disenfranchisement, unequal education, or racial segregation. They were fighting the trucking of PCBs (polychlorinated biphenyls) into a landfill sited in their neighborhood.

Since the 1920s, PCBs have been valuable in industry because they are resistant to acids, bases, and heat, which makes them useful as insulation in electrical equipment such as transformers (devices that use induction to transfer electrical energy between circuits) and capacitators (electrical components that store potential energy in an electric field) as well as lubricants. Although their toxic effects led to their U.S. manufacture being banned in 1979, PCBs from other countries and those that persist in the environment still pose a threat to Americans. They linger in many other products and applications, from flame retardants to paints, coatings, adhesives, and inks.1

Marchers’ shouts demanded and their placards read “No PCB,” “Landfills Kill,” and “We Care About Our Future: Don’t Harm Generations to Come.”

After the victories of the civil rights movement, including the end of de jure racial segregation, African American residents of neglected communities took aim at a different kind of racial sequestering. They began to demand equal access to clean land, food, air, and water through lawsuits, political demands, and civil disobedience. Afton was one of the first communities of color to fight its selection as a dumping ground for garbage and toxic wastes. It certainly was the most influential: it is no exaggeration to say that the people of Afton ignited the global environmental justice movement through their civil disobedience. It was an idea whose time had come.

As the state made good on its threat to jail the protesters, the sheriff’s invocation of law and order was ironic: it was Afton’s residents who were the victims of interstate criminal activity.

The crime spree had begun in the middle of a night in late July when Robert Burns of Jamestown, New York, drove his specially outfitted truck to North Carolina under cover of darkness. Accompanied by his two grown sons, he made the illicit pilgrimage to save money by surreptitiously spewing 31,000 gallons of toxic oil along Carolinian roadsides instead of disposing of it safely and legally. These midnight forays continued for two weeks along more than two hundred miles of the state highways. Burns left meter-wide swaths of earth contaminated with carcinogenic PCBs, dioxins, and dibenzofurans.

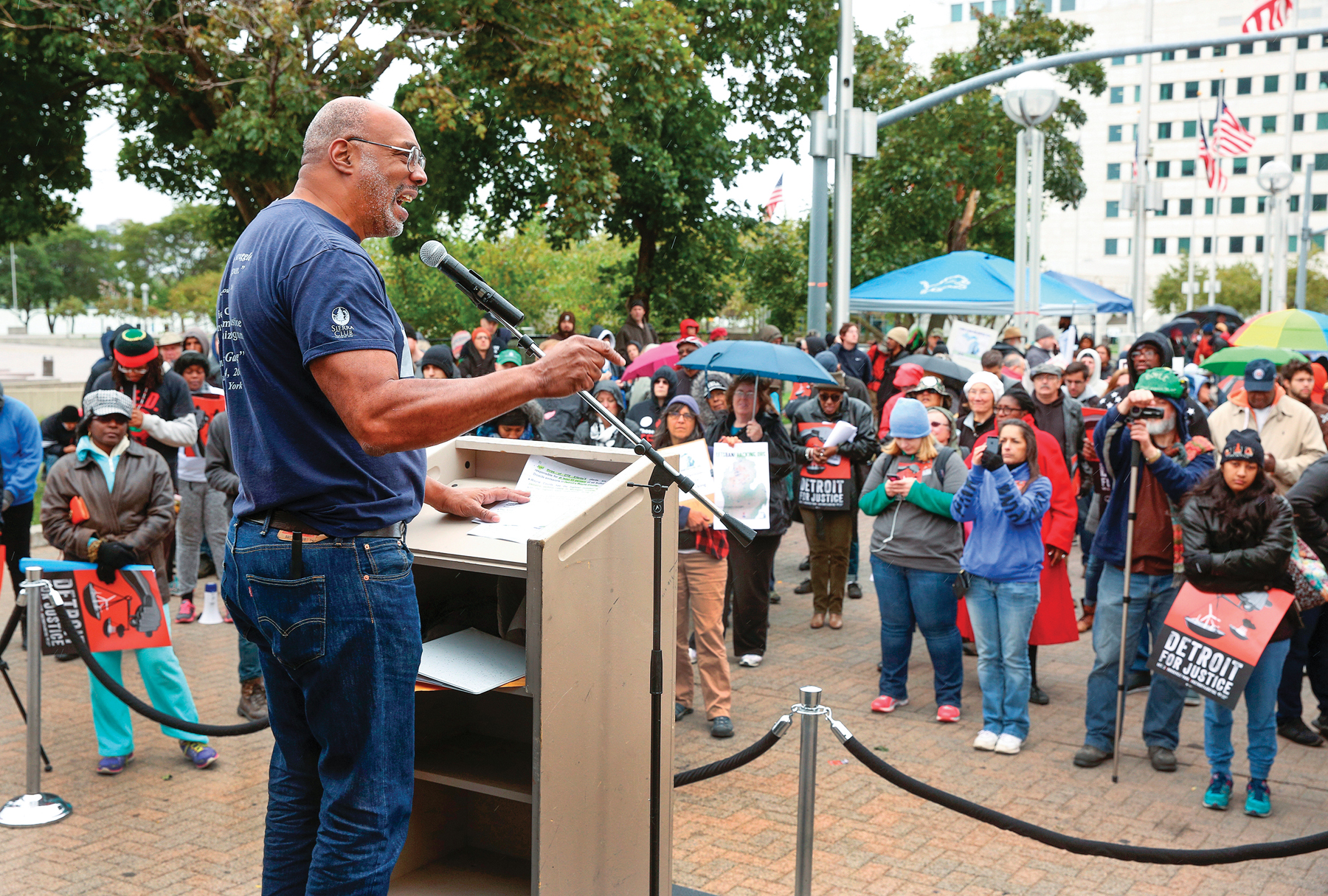

Civil rights activist Benjamin Chavis leads protesters against illegal PCB dumping in the mostly African American town of Afton, North Carolina. (AP Photo/Greg Gibson)

The poisoned oil had come from the Ward Transformer Company of North Carolina, one of the nation’s largest transformer repair companies. Its owner, Robert E. Ward Jr., was Burns’s business partner. When the illegal dumping was discovered, Burns was sentenced to three to five years in a North Carolina prison and Ward was convicted of violating the Federal Toxic Substances Control Act and sentenced to eighteen months in prison and fined $200,000.2

The state’s attention quickly turned to protecting its citizens from the disease-causing chemicals, notably PCBs, which were then known to cause birth defects and liver and skin disorders and were strongly suspected of causing cancer. Although PCBs’ ability to erode intellectual functioning was not yet well established, today we know that PCBs are also endocrine disruptors that profoundly damage the brains and impair the intellect of fetuses and the young, as explained in Chapter 3.3

“We know why they picked us”

Alarmed by the dire health effects posed by the 50,000 tons of soil soaked in a witches’ brew of PCBs, dioxins, and other poisons, Governor James B. Hunt Jr. militated for its disposal in predominately African American Warren County as the “best available site.”4 However, scientific criteria, such as the distance from groundwater or likelihood of leaching, did not support his administration’s description of Warren County as the “best” site.

“We know why they picked us,” declared the Reverend Luther G. Brown, then pastor of Coley Springs Baptist Church. “It’s because it’s a poor county—poor politically, poor in health, poor in education and because it’s mostly black. Nobody thought people like us would make a fuss.”5

But Afton residents made a widely resounding clamor, and a smart one: they recruited support from neighboring sympathizers and organizations in order to do so. The Coley Springs Baptist Church, the county chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, and twenty-six neighbors joined them in filing a lawsuit in Federal District Court to block the dumping of PCBs.

This coalition charged that by ignoring more scientifically suitable alternative sites, EPA officials and the State of North Carolina practiced racial discrimination against the citizens of Warren County.

An unsympathetic judge, W. Earl Britt, removed the last legal hurdle between Afton and the PCB dumping when he ruled against the residents, declaring from his bench, “There is not one shred of evidence that race has at any time been a motivating factor for any decision taken by any official, state, federal or local.”

This is despite the fact that Title VI of the 1964 Civil Rights Act directs that “No person in the United States shall, on the ground of race, color, or national origin, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any program or activity receiving federal financial assistance.”

Neither did the EPA protect Afton’s residents. Instead, it paid $2.54 million to fund the digging up and trucking of the poisoned earth to Afton, in effect sponsoring the pollution of Afton and its environs. This time, the deadly chemicals would be dumped openly, in the light of day and with the blessing of the state and the EPA.

In response, Afton’s residents and their supporters took to the streets to resist the dumping, mounting one of the longest and most widely publicized mass demonstrations and igniting the global environmental justice movement.6 The Washington Post described the PCB protest movement as “the marriage of environmentalism with civil rights.”7

Congress Takes Note

Afton inspired more than activism by other targeted communities. It inspired the research that is essential for documenting the racial nature of such deadly exposures.

Congress took notice of the protests, and the very next year the U.S. General Accounting Office reported to the Committee on Energy and Commerce8 that three of every four landfills it looked at were located in the region’s poorest communities. However, the GAO specifically declined to investigate race as a factor in the siting of industrial landfills, a prescient omission that helped elide the role of race in some environmental poisonings.

But sociologist Robert Bullard already knew race to be a determining factor in communities he had studied, such as Houston. His 1979 study had discovered that all five city-owned landfills were located in black neighborhoods. Moreover, “Six out of eight city-owned incinerators were in black neighborhoods,” he recalled in a 2017 interview with the Union of Concerned Scientists. “And more than 80 percent of the garbage dumped in the city from the 1930s up to 1978 was being dumped in black neighborhoods. Black people only made up a quarter of Houston’s population at the time.”9

Bullard set out to investigate and quantify the role of race in other parts of the nation. His meticulous assessments while a professor at Texas Southern University in Houston correlated census tract and other demographic information, including race, with toxic exposures. With these data, he demonstrated the determinative role of race. In 1987, a more expansive survey by the United Church of Christ Commission for Racial Justice completed an inclusive national report revealing that hazardous waste facilities in the United States are more likely to be located in predominantly minority communities such as those Bullard studied in Dallas, Texas; Alsen, Louisiana; Institute, West Virginia; and Emelle, Alabama, than in white areas.10 This overrepresentation of environmental hazards and the concomitant increased health risks were detailed in his many books such as 1960’s Dumping in Dixie: Race, Class and Environmental Quality.

Within a decade, follow-up studies verified that this racial disparity had worsened. Such data quantified a racial factor in the siting of toxic wastes that had heretofore gone undocumented, and these data are essential to crafting political public health solutions that acknowledge the engineered vulnerability of African Americans and other Americans of color.

It was the organized efforts and persistence of Afton activists that drove the government interest. “These were invisible problems in invisible communities until they organized themselves and started to have their own dialogue with EPA,” said Vernice Miller-Travis, of the Office of Environmental Justice advisory council.

Afton’s own landfill battle has not yet been won because the PCBs that were dumped in 1982 remain.11 But its residents put into motion a global sea-change larger than the activists could have foreseen.

In its 1994 Environmental Equity Draft, the EPA described Afton’s PCB protests as “the watershed event that led to the environmental equity movement of the 1980’s.” The people of Afton catalyzed the birth of a global resistance movement to free communities of color from the physical and, as we now recognize, the mental fetters of environmental poisoning. Afton’s playbook still holds lessons for the sickened and endangered.

In 1992 while a graduate student in Boston, I met Mary Ann Nelson, a Cambridge lawyer who was an executive of the Greater Boston Sierra Club. I had never before met an African American who held a leadership role in a mainstream environmental organization; although there are now many, there then were not nearly enough. I approved of the environmental agendas of groups like the Sierra Club and the Nature Conservancy, which included protection of wild places and endangered species; preserving water and air purity; working for a “clean energy” future, curbing climate change, and maintaining pressure on politicians and corporations to ensure healthy communities.

But for a long time, I couldn’t help but think of these goals as tangential to the life-and-death struggles of people of color, whose very ability to breathe, think, and live a normal healthy lifespan is directly threatened by environmental crises. Today their interests are quite congruent and their partnerships with communities of color seem natural alliances brokered by visionaries like Professor Robert Bullard and Dr. Aaron Mair, who became the first African American elected as Director of the Sierra Club in 2015.

Conventional wisdom had long fed a misperception of African Americans as divorced from the joys and health benefits of nature. In 1969, an R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Company advertising memo advised against showing African Americans in outdoor settings. It claimed that “… the ‘Outdoors’ (hunting, skiing, sailing) is not felt to be suitable, as these are considered unfamiliar to the Negro…”12

The early research of Robert Bullard, “the father of the environmental justice movement,” revealed the nature and extent of selective environmental poisoning in neighborhoods of color. (AP Photo)

Aaron Mair (AP Photo/Rex Larsen)

Today, this widespread misconception that African Americans do not seek and enjoy communing with nature persists, fed by a number of biases. The relative absence of African Americans in some national and public parks, swimming pools, and similar sites reflects not indifference but the past violent prohibitions against their presence. Robert Bullard points out that today a dearth of mass transit makes many such refuges inaccessible to urbanites.

But as I spoke with the Sierra Club’s Mary Ann Nelson about her work, I remembered how formative my daily interactions with nature had been as a child. I felt that days spent roaming the woods and fields of Croton-on-Hudson; Fort Dix, New Jersey; and Aschaffenburg, Germany, while learning firsthand about nature contributed to both a lifelong appreciation of biology and a happy childhood. My friends from the Dominican Republic and Virgin Islands also wax nostalgic as they speak of growing up surrounded by natural beauty. We’re now confirmed urbanites, but we agree that something has been lost in trading unspoiled nature for the streets of New York City and Chicago.

Recent research shows us that this yearning for natural surroundings reflects more than sentiment. We now know that exposure to the natural world is essential to a child’s health and development—and to the health of the adult she will become.13

A Natural High

A growing body of research supports the positive connection between exposure to the natural environment in childhood14 and better health at all stages of life.15

Stress—physical, psychological, or some combination of these—is an inescapable part of life. Responses to stress can be productive, even necessary, but severe or unremitting stress can damage one’s physical and mental health. Various species of racialized stress have been implicated in everything from hypertension to suicide.

We most often read and hear of malignant stress arising in direct response to a stressor such as a threat or perceived threat.

But this is not the only overarching theory of stress. In February 2018, a trio of researchers investigated how living within unsafe environments generates a constant stress response. Writing in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, they discuss stress-fueling features of such toxic environments, such as: low social status, early (including prenatal) adversity, loneliness, and “lack of a natural environment.”

They also discuss biological mechanisms for these: loneliness, for example, seems to drive up stress levels by chronically decreasing heart rate variability (HRV),16 increasing cortisol levels, and distorting immunity mechanisms.

The stress caused by such factors can be curtailed, or “turned off” only when safety is perceived. Exposure to the natural environment is one of many factors capable of turning off chronic stress by triggering a perception of safety. The University of Leiden (Netherlands) authors argue that within this “generalized unsafety theory of stress (GUTS)” the environment provides the physiological substrate for the underpinning of some things we share with most other animals: fear of the unknown. From birth we have a low tolerance for uncertainty that results in a stress response that is always turned on—until we perceive signs of safety. Indications of safety disarm the stress response and in so doing they mitigate the risks of stress-related diseases like hypertension affective disorders and even obesity.17

The authors theorize that the prefrontal cortex, which usually suppresses brain structures such as the amygdala18 and neural activities that mediate the stress response, especially the amygdala, do so only when the brain has perceived safety.19 If safety is no longer perceived, these neurological “brakes” are lifted, and the amygdala reverts to high gear, quickly restoring the body to “fight or flight” mode. Heart activity increases, and blood pressure rises, and other stress responses resume.

The prefrontal inhibition of the stress response lasts only as long as the perception of safety, which in many urban environments is rarely for long. The authors note that chronic stress may be an especially important risk for African Americans.

A well-known example of membership in a discriminated minority with serious health consequences are African Americans in the United States who have lower life expectancy than their compatriots,20 and it is believed that discrimination significantly contributes to this difference.21 The lifetime burden of perceived discrimination and discriminatory harassment and/or assault is associated with higher blood pressure, especially ambulatory and nighttime diastolic blood pressure22 and higher levels of inflammatory markers. Again, since it is unlikely that these chronically enhanced physiological effects are due to actual discrimination-related stressors alone, or to continuous conscious worrying about it, it seems more likely that for many African Americans daily life is unconsciously perceived as less safe than it is for others.

Previous studies have already suggested that exposure to natural rather than urban environments reduces anxiety and feelings of sadness, and normalizes heart rate, cortisol, and blood pressure even when confounding factors such as socioeconomic status, exercise levels, noise, smells, and crowding are controlled for.23 Even viewing pictures of unspoiled nature shows some of the physiological effects.

Combating environmental poisoning is critically important, but like everyone else, African Americans, Hispanics, Asians, and Native Americans need access to untrammeled nature to optimize our mental and physical health.

Over the past few decades, these two poles of the environmental movement have come together over common concerns. Mainstream environmental groups have shown their worth as powerful allies of environmental justice activists and have embraced its tenets. As early as 1994, the Sierra Club published Unequal Protection: Environmental Justice and Communities of Color and followed this in 2005 with The Quest for Environmental Justice: Human Rights and the Politics of Pollution. In 2013 the Sierra Club gave Robert Bullard its top honor, the John Muir Award, and has established24 an annual award to an individual or group that has done outstanding work in the area of environmental justice.

Linking Arms

As Afton showed us, communities of color acting jointly, even without significant wealth or political clout, have been far more effective than any number of individuals acting alone. And just as these first organizers did, don’t forget to utilize preexisting groups if they are committed to environmental health or if you and your neighbors can inspire them to commit.

Here are steps to help you organize for the environmental health of your community:

Look Beyond Just Your Friends and Neighbors

Recruit your friends and neighbors, but also ask your church, sorority, and any other local groups to which you belong for their support.

As noted in Chapter 6, the EPA’s “Guide for Community Partners,” a blueprint for organizing, can be downloaded from https://nepis.epa.gov/Exe/ZyPDF.cgi?Dockey=P1004WLH.txt.

A website will help your group to share information and keep each other informed. It will also let others know what you are doing and about new issues as they arise. As a group, you will decide upon your goals for your community’s health: Do you want a polluter’s factory shut down? Do you want them to pay for cleanup? For testing of your children and homes? To establish a free clinic and medical bills resulting from the poisoning? To buy your homes sparing you the burden of trying to sell tainted property? Payment for damages? All these things have been achieved by communities just like yours. But you need a goal, a plan, and expert advice.

Don’t be intimidated by the complexity of the work ahead of you because professionals with expertise in community organizing, law, and devising media campaigns are ready to help you. With such help, other groups have attained their goals, and you can too. Your church, temple, or other faith community can be a powerful ally to take on the dangers and inequities of environmental poisoning in your homes and neighborhoods, just as Afton’s protest was strengthened by the Coley Springs Baptist Church and as the modern environmental racism movement was bolstered by the work of the United Church of Christ. Given the church’s pivotal role as a seat of political and moral power behind every blow to violent racism, from abolition to desegregation to health disparities and environmental racism, the faith community has repeatedly shown itself to be an inspired agent of operation.

But it’s not the only one.

Explore whatever organization you are active in to determine whether they are also potential partners for working to end the environmental poisoning of communities of color. Your sorority or fraternity, other social organization, your union, alumni group—whatever group in which you invest your effort, time, and heart—may be interested in pursuing health and social justice for marginalized communities: you’ll never know until you ask.

The more you are able to tap into and mobilize existing organizations, the more efficient your efforts can become. Your group may find it helpful to read about other examples of environmental racism across the country, such as the ravaged communities described in this book. This may help you to understand the common actions and challenges as well as the strategies that polluters have embraced to evade detection, regulation, and justice.

It’s important to learn that such communities are populated by middle-class as well as poor people of color, as in Anniston; that siting of such waste dumps is not always based on logical or scientific criteria as governments claim; that environmental waste and garbage services sometimes fail to provide minimal support as happened in Houston and Dunbar; that polluting industries or waste dumps were often imported without warning or acknowledgment of their hazards; that people are sometimes blamed by polluting industries for their deteriorating health as the Lead Institute blamed the “uneducable” parents of lead-poisoned black and Puerto Rican children, as municipal bureaucrats blamed parents of poisoned Baltimore children and later the water customers of Flint, Michigan, for poisonings that the city engineered. Knowing this history can protect activists against succumbing to intimidation when experts intimate that poisoning woes are the fault of the victims or that the science dictating their actions is too complex for laypeople to understand.

Learn Where and How to Report Environmental Violations

Go to www.epa.gov/enforcement/report-environmental-violations. Complaints can be filed at www.epa.ie/enforcement/report/.

Hold Community Meetings

Post flyers throughout the neighborhood to invite everyone affected to the meetings and keep in touch by telephone/e-mail.

Write a Description of the Problem

You may have received health notices or read newspaper accounts of the poisoning that can help you with this. EJSCREEN, the environmental justice screening and mapping tool at https://www.epa.gov/ejscreen, can also be a very useful aid in characterizing and documenting the pollution problems in your community. It can also show you if neighboring communities are suffering from toxic exposures. If nearby communities have similar issues, try to join with them.

Align with Other Environmental Organizations

To find national environmental justice allies, use the map of Environmental Justice Health Alliance members who have freed themselves from environmental poisoning, often through coalitions of diverse organizations. The map is at http://ej4all.org/affiliates/. Join with organizations such as the Sierra Club and the Nature Conservancy, which work for stronger environmental and energy laws to reduce pollution and fossil-fuel dependence, to protect U.S. waterways and wildlife, and to preserve the wild. Their missions include keeping our air and water clean and replacing “dirty” fuel sources, ensuring a clean energy future. This makes their goals congruent with the struggles of those facing environmental racism.

Seek Legal Counsel

Before taking legal action, I strongly suggest that your group first contact a lawyer or Earth Justice, a legal agency that holds those who break our nation’s laws accountable for their actions. Finding a legal ally or advocate is the best way to learn your legal rights and to decide which specific legal steps are most likely to bring you the results you want. If your group decides to file formal complaints or to sue, the paperwork involved can be complicated. Filing the wrong form and documents, completing them incorrectly, or filing them with the wrong agency can delay your relief. For free legal help in all this, as well as help in organizing around environmental dangers, consider consulting Earth Justice (https://earthjustice.org), which bills itself as “the nation’s original and largest nonprofit environmental law organization.”

This legal organization is currently pursuing approximately four hundred cases that focus on a variety of environmental concerns, including advising and offering free legal assistance to community groups who seek to end environmental assaults. (To obtain its detailed advice for community organizing, go to https://earthjustice.org/healthy-communities.) In order to end environmental injustice, you need to take the correct legal steps, warns Earth Justice, which offers free legal help around environmental concerns because, the group’s website says, “The Earth needs a good lawyer.” So does your community. You can reach Earth Justice at 800-584-6460 or via e-mail at info@earthjustice.org.

Make Your Concerns Known to Your Congressional Lawmakers

To find out who your senators and other elected representatives are, and how to contact them, go to https://earthjustice.org/action/faq#congress.

Take Advantage of Free Training

Look into the three-day Environmental Justice workshops conducted by the United Church of Christ. You can sign up at http://www.ucc.org/centers-for-environmental-justice. Representatives from your group should consider attending one; then they can take what they learn about developing community-based strategies and partnerships across ethnic and environmental interests back to your advocacy group, neighborhood, and city.

Apply for Grant Funding

Since 1994, the Environmental Justice Small Grants Program has awarded $24 million to more than 1,400 community-based organizations. For advice and/or funds to cover your group’s expenses, contact the Office of Environmental Justice (OEJ) at https://www.epa.gov/environmentaljustice, especially “Environmental Justice Grants and Resources.” Native American communities should contact the National Environmental Justice Advisory Council and Environmental Justice for Tribes and Indigenous Peoples at https://www.epa.gov/environmentaljustice/environmentaljustice-tribes-and-indigenous-peoples.

Devise a Media Strategy

After your organization decides upon its focus and goals, develop a media strategy to make more people aware of the problem. Recruiting an experienced media professional is crucial. Try these steps:

Visit the United Way (https://www.unitedway.org) for information on how to access volunteer media professionals.

Contact Encore Talent Works (https://toolkit.encore.org) for access to a media consultant.

Contact your local television news stations to explain your community’s plight.

Write to your local print and online news outlet(s). For guidance on how to write an effective action letter, see https://earthjustice.org/action/faq#effective.

Challenges still confront those working to heal the poisoned world that sickens and confounds Americans, especially people of color. The concentration of toxic industrial wastes in ethnic neighborhoods remains—maintained by the polluters’ callous denialism, clothed in the scientific lingo of “insufficient evidence,” and joined by perennial “blame-the-victim” responses. This intellectual shrugging-off of mass poisoning is paralleled by other apostles of futility: namely, hereditarians who are wedded to the notion that innate, irredeemable racial deficiency, not the slow violence of widescale poisoning, impairs cognitive and behavioral functioning in America’s ethnic enclaves.

But we know better. Problems stemming from brains injured by toxic exposures have solutions. From modest communities in Anniston, Dunbar, and Flint to mammoth ones like Baltimore, New York, and Washington, people of color and their white supporters understand that they must force government action to banish lead, mercury, industrial waste, and air pollution from cities, fence-line communities, Native American reservations, and “Cancer Alleys.”

Many have traced the history of polluting U.S. corporations and shown they find it profitable to deny responsibility for death and disease, so we can’t be surprised that industries still deem the costs of testing, cleanup, and abatement too great an expense to preserve the lives, health, and minds of millions. Neither is the concentration of toxic killers and disablers among the racially marginalized shocking: it’s happened too consistently to astonish us.

Moreover, the EPA has reached a nadir of malign neglect, signaled by Trump’s appointment of Scott Pruitt, whose avowed aim was to dismantle the EPA. The rolling back of protections continued after his departure, hobbling efforts to provide potable water and curb emissions of toxics-spewing, mercury-producing coal-fired plants, while green-lighting questionable chemicals like chlorpyrifos. There’s no denying that this diminution of our already feeble environmental-protection standards is discouraging.

So, what’s the good news?

The odds seem stacked against those who militate for environmental justice, but this was precisely the case during the civil rights era, when activists persisted and won in the face of widespread murders and other unpunished violence, as well as in the face of hostile legal systems that protected segregation, lynching, unjust imprisonment, and marginalization. In rose-colored retrospect, it may appear as if the larger American public and news media championed civil rights workers, but many demonized them, calling for “law and order.” Even the beloved Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was, at the time of his death, widely derided as an immoral race-baiter and communist.

Yet he helped inspire the victorious civil rights warriors we now revere as heroes who saved the nation’s justice system, and its soul. They would not stop until they won, and neither should we.

Today, activists of color and their white supporters in Flint, Anniston, Standing Rock, and smaller communities resist chemical oppression, just as the people of Afton refused to accept interstate transport of PCBs to poison their land and water.

Today, the activists do not battle corporate scientists and an indifferent government entirely on their own. The research and humanity of scientists like Herbert Needleman, Robert Bullard, Philip Landrigan, and Philippe Grandjean have armed them with a true picture of how industrial and environmental poisons damage minds as well as bodies. Lawyers like Suzanne Shapiro, Evan K. Thalenberg, and Thomas Yost have held corporations and institutions accountable for damage to the minds of lead-poisoned African American children.

And today a new generation of scientist-activists of color, such as Aaron Mair, the first African American director of the Sierra Club; Marsha Coleman-Adebayo, senior policy analyst for the EPA; and Mustafa Ali, cofounder of the EPA’s environmental justice program, deploy their expertise and their passion for justice in this new civil rights movement that will win clean air, land, housing—and brains unimpaired by poisons.