7. Just Cruisin’ with Harry Pidgeon

He was not only a person who calmly reported sharks snuffling at his toes as he climbed out of the water, but Harry Pidgeon seems by all accounts to have been a remarkably capable man who might fell a patch of forest, build himself a log cabin, and then later softly mention that he’d been studying origami so he’d like to fold you a pink crane or two. Joshua Slocum had a curmudgeonly side; you’d want to learn from him, but you get the sense that he’d make you feel a fool in the process, maybe even on purpose now and again. Pidgeon, by contrast, his hands just as rough and chipped, perhaps because he had never served as a ship’s master, seems to have had an easy-going, non-judgmental competence that would put you at ease. Pidgeon’s two solo circumnavigations, beginning in the 1920s, represent a new trend in why-go and what-they-saw because primarily he wanted to visit the islands of the South Pacific—then once underway he fell in love with life at sea. As a relative amateur, Pidgeon did all this on a boat that he built himself from a plan published by a weekend-warrior boating magazine called The Rudder, which had started in the 1890s.

Born in 1869, a quarter-century after Slocum, Harry Pidgeon grew up as part of a large family working a farm in Iowa. When he was eighteen he found a job on a ranch in California, and then spent a summer up north where he built a boat with a friend and ran the rapids of the Yukon River. In southeast Alaska he owned his first boat and cruised along the coast. From here he continued his lifelong walkabout, building a raft and sailing down the Mississippi. Pidgeon then traveled overland back to California, where, now in his late forties, he decided to build his own boat for blue-water sailing. He bought the plans through the mail and constructed from scratch a thirty-four-foot ketch out of plywood and other timbers, using hand tools, on a vacant lot beside Los Angeles Harbor. Another man nearby was building a multi-storied ark in anticipation of The Flood.

As Pidgeon was completing his boat, which he named Islander, a friend invited him and two others for a sail to Hawai‘i. On the first day out, the weather was rough. They all got seasick, vomiting plums over the side. Pidgeon found himself steeled to the expedition, though, even as the others were down below incapacitated. He was disappointed when his friend directed the boat to head back home.

“I returned to the Islander with a feeling,” Pidgeon wrote, “that the problems of a single-handed sailor were comparatively simple.” In other words, if you go it alone on a boat (or in life), you don’t have to worry about other people’s schedules or needs.

Having taught himself navigation at the public library, Pidgeon decided to sail his new boat to Hawai‘i from Los Angeles, a distance that is only a few days shorter than an entire trans-Atlantic crossing. Once underway, Pidgeon stopped bothering with dead reckoning and multiple sun sights, since working with the mathematical tables down below made him seasick. With an accurate chronometer—more advanced and reliable than Slocum’s tin clock—he obtained his daily latitude with a single sun sight at local apparent noon each day—when the sun is at its highest point. He compared this timing to that of Greenwich, with his tables, and thus roughly estimated his longitude, too. A fix once a day was all he needed on this passage, as he sailed for three weeks with favorable trade winds along a latitude, more or less straight across over to Hawai‘i. He saw only one other vessel during the whole trip, a long four-masted schooner piled high with lumber. He followed it for as long as he could, which, combined with the mountain peaks of Hawai‘i in the coming days, helped him navigate the final leg with relative ease.

Pidgeon was not yet convinced that sailing alone was for him, though. He made a friend with whom he sailed back to Los Angeles, but once there, after getting no firm commitments from anybody to join him for a sail to the South Pacific, Pidgeon just figured it best to go alone or the trip would never happen. He had read Slocum’s Sailing Alone Around the World and had spoken to a few cruisers, but completing a circumnavigation was not in his plans at first. Pidgeon just wanted to travel and to have a cheap floating home.

If escaping modern civilization was on Pidgeon’s mind, he did not share this in his account of the voyage, titled Around the World Single-Handed (1928), although there was plenty from which to flee in 1921. The city of Los Angeles had been entirely shut down to try and stop the spread of the Spanish Flu, a horrific pandemic that killed whole groups of young people who bled out of their eyes and ears. The quarantine of the city began in the harbor where Pidgeon built his boat and the pandemic lasted into 1919, while the local government closed schools and businesses. Los Angeles fared better than most other American cities, but it still lost nearly 500 people for every 100,000. Meanwhile, the legacy of World War I remained raw. Too old to enlist and having been raised a Quaker, Pidgeon had not served in the military.

When Pidgeon first sailed to Hawai‘i on his shakedown cruise, he was fifty-one. This was the same age as Joshua Slocum when he left Boston. (That’s my age, too, as I write this.) Fifty-one was also the same age as Don Quixote, one of Slocum’s favorite fictional characters, that soft-handed Spanish gentleman who is so entranced by his books that he hoists on some old knight’s armor and saddles up an aging horse named Rocinante to walk out his back gate to try to achieve fame and fortune by behaving in the old ways as a knight savant. Don Quixote lives in his imagination and yearns to serve a world that has long since moved on. Go to nearly any marina today anywhere in the world and you’ll find a Don Quixote, half-mystic and half-fool, applying another coat of varnish to the rail of his old, beloved Rocinante.

Harry Pidgeon sailed without any significant incident to the South Pacific. As he traveled from place to place, he began to grow more confident.

“I had found the sea to be a great highway leading to wherever I wished to go,” he wrote. Pidgeon learned to balance Islander’s steering with the sails, and if his boat “did run off course a bit, what of it?”

He tightened up his navigation when he needed to, now tracing through the low island atolls. He rarely traveled with an extensive collection of updated charts, nor did he have any previous experience in these places. No one wore safety harnesses back then and his boat had an even lower rail than Slocum’s Spray. Yet Pidgeon cruised throughout the South Pacific, with the most exciting event, as he tells it, being when some Americans took him for an automobile ride around Papeete, on Tahiti, and their car flipped over at a sharp turn.

Pidgeon continued on to cruise aboard Islander from anchorage to anchorage. He took photographs of topless women in Samoa. He photographed Melanesian men in loincloths with huge heads of hair. He photographed tattoos, traditional craftwork, a curly-tusked pig bred for sacrifice, and he climbed hills and took photographs of his boat in tropical bays and harbors. He wrote of customs and quarantine procedures, shifts in the historical diet of Pacific Islanders in the wake of colonial epidemics, the landing sites of Herman Melville and Robert Louis Stevenson, and the taste and effects of kava and the betel nut. By the way Pidgeon told it, he was on a long Sunday amble across exotic Oceania.

After nearly two years, he sailed Islander north of Australia where he joined the “route of Captain Joshua Slocum,” the westbound path to follow into the Indian Ocean, South Atlantic, and the Caribbean. Pidgeon decided, aw shucks, that he intended to be the second person to circumnavigate the world alone, and that he would be the first to do so via the Panama Canal.

After the automobile crash in Tahiti, Pidgeon wrote of only two more significant brushes with danger, both of which occurred at sea after rounding the Cape of Good Hope.

The first happened after a long, lovely stay in Cape Town. He began his sail north along the coast, but the wind was light, so he wasn’t able to get much rest being too close to shore. By the third night he was able to get a little farther out to sea, so he lashed his tiller, checked his sails, and went below to sleep. He woke up to Islander scraping on the beach, thrashing in turbid white water. The wind had shifted and his boat had sailed itself into danger. Looking over the rail at two in the morning, Pidgeon thought this was the end of his trip. Islander washed helplessly higher and harder on the beach. By daylight it was low tide. He jumped off the boat into the surf to go search for help, looking back at his home heeled perilously on its side as it suffered, thumped and lifted by incoming waves.

Pidgeon would learn in the coming days, the glass-half-full news story in the local press, that he had been almost supernaturally fortunate. This was the only sandy beach along a ten-mile coastline of rock cliffs and ledges, and, even here, if there had not been a favorable high tide at the moment Islander sailed in, the outer rocky reef would have ripped out its keel as it steered itself into the bay.

With Islander restored, Pidgeon sailed into the South Atlantic and westward to the mid-ocean island of St Helena. Here he met a Mr. R. A. Clark, who remembered hosting Joshua Slocum twenty years earlier. When writing about this amble around St Helena with Clark, Pidgeon waxed nostalgic in a fashion that Slocum would have appreciated: “In the days when the commerce of the world was carried on in sailing ships, St Helena lay right in the track of the homeward bound East Indiamen . . . Then it was a prosperous place, but steamships and the Suez Canal have left it only an island of romance.” By the 1920s steam vessels had taken over nearly every trade and route. Masts and canvas remained only on coastal boats sailing among island nations and on a few enormous old sailing ships with iron hulls that carried huge bulk cargoes, such as grain and guano.

Pidgeon’s second near-disaster came at the hands of a steamship captain off the coast of Brazil. This happened near the equator in the shipping lanes. Pidgeon watched a steamship with a load of lumber on deck. “In all my voyage I had never met a vessel within hailing distance,” he wrote, which speaks to both his route and the lack of global shipping in the 1920s. He was curious as to what people on a large ship would think of meeting his little boat out at sea. He would be sorry what he had wished for, because in heavy seas the following evening, a full moon, when all looked clear enough for him to go below for a rest, he woke up to a crash:

I sprang up to see the dark hull of a steamer looming alongside. My first thought was that she had run into my vessel, but she was going on the same course as the Islander, and at the same speed. If the crew had seen my boat in time to slow down, why had they not kept away? I threw the tiller over and tried to bring my boat up into the wind, but she was in too close contact. There I was with my boat on the windward side of the steamer, and every sea washing her up and down the iron side. In one of her upward rushes the foremast speared the steamer’s bridge. In the bright moonlight I saw a row of faces lined up along the steamer’s waist and peering down at me.

As Pidgeon desperately tried to reduce the damage, Islander heaving up and down with the seas that washed him violently against the tanker’s hull, the chief mate threw a heavy rope down that hit the solo sailor on the head. They were trying to rescue him.

Now the Quaker farm boy began to get angry.

“I was somewhat excited, so my answer was not polite! What do I want with your rope?”

The whole matter with this ship only lasted about five minutes, but before returning to its course towards Buenos Aires, the vessel, which he would later learn was the oil tanker San Quirino, rolled steeply toward Islander. The backwash sent Pidgeon’s boat clear, but not before a final collision broke parts of his mizzen boom, bowsprit, and damaged the foremast and jib stay.

In the morning, as he sawed off two-thirds of the remaining bowsprit and re-rigged the boat, a shark patrolled just underneath him. “As a species that I had not seen before, he interested me greatly,” Pidgeon wrote, “but if he was expecting me to furnish him his dinner, he was disappointed.” By the end of the day, under shortened sail, Pidgeon was able to continue on to the Caribbean.

In Trinidad, as he repaired and repainted his boat, Captain Pidgeon received a tour of a visiting cruise ship as an honored guest. He walked the stairways, looked upon the shipboard pool and the shipboard golf course, and he marveled at all the windows. But the view from so far up on the bridge made him lonely. “I liked my way of seeing the world best, and sometimes one of the tourists confided that he envied me my independent way of voyaging.”

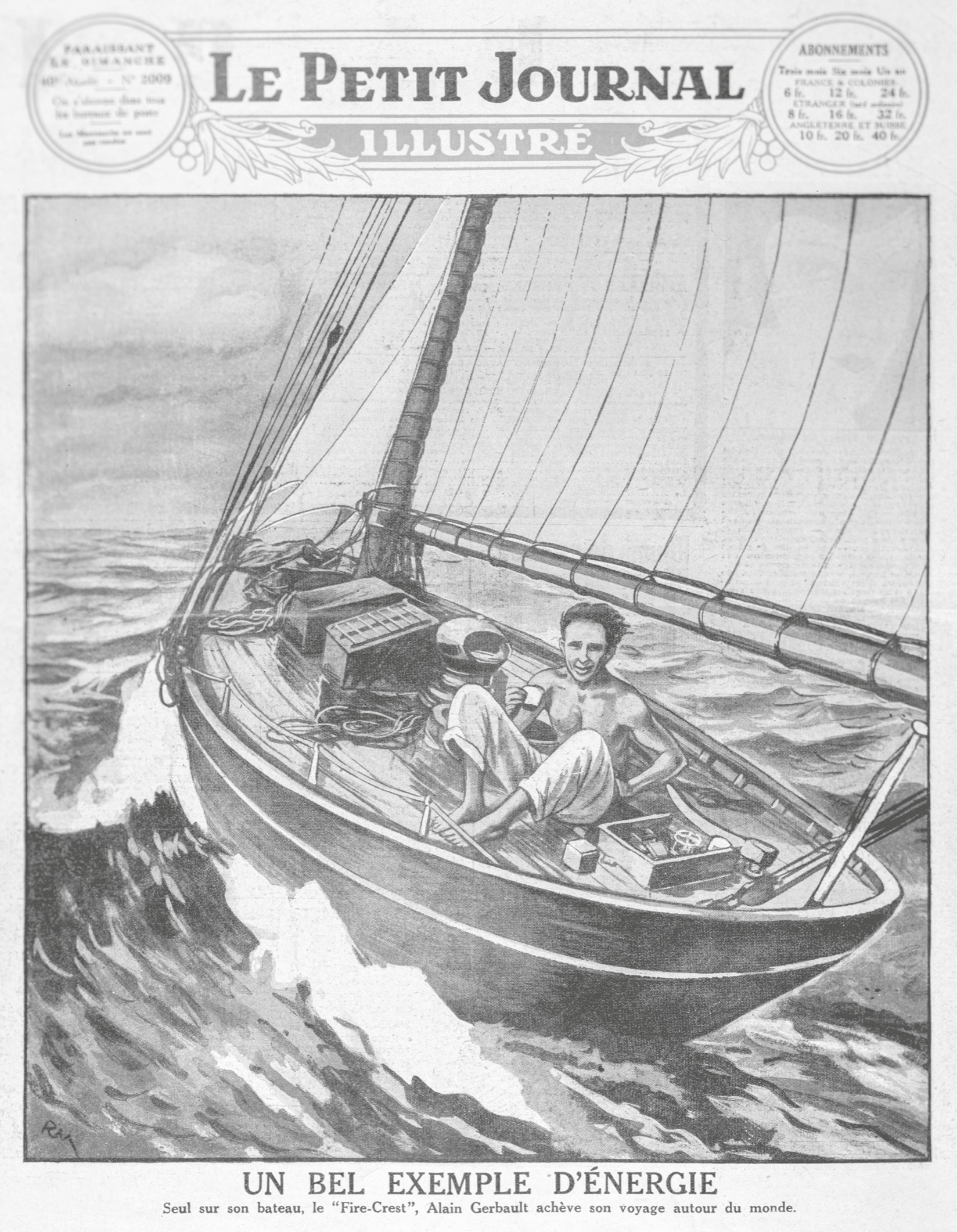

Pidgeon sailed on to the Panama Canal and took Islander through, despite his outboard engine not working for the one time he really could have used it. Once safely on the Pacific side, planning an inland photography trip, he had a chance meeting of sacred significance in single-handers’ lore. On 12 May 1925, Pidgeon gammed with the famous Frenchman Alain Gerbault, who was bound alone for the South Pacific aboard his own boat. Gerbault would in a couple of years succeed with his own single-handed circumnavigation, the third person to do so.

Gerbault and Pidgeon could not have been more different. Gerbault had come to sailing as a veteran, a disaffected fighter pilot who sought the sea for solace in the boat he had planned to cruise with two of his friends who had died in World War I. Before entering the war, Gerbault had been a champion tennis player. He was young, handsome, dynamic, and his sailboat was tender, uncomfortable, and wet—a racing yacht built for speed but not for cruising comfort. He’d already done a trans-Atlantic crossing with this boat, during which he had endured an epic passage of over one hundred days with rotting rigging, threadbare sails, a rogue wave that broke his bowsprit, and a barrel of spoiled water. Yet Gerbault survived that first crossing and was crowned a hero on his arrival in New York City in 1923, garnering more fame for himself, even as Harry Pidgeon, lesser known, smoothly skimmed ever westward around the world. Gerbault—who carefully described the books with which he sailed, his favorite poet being John Masefield, and Joshua Slocum’s book at the top of his list of sea narratives—had sailed from New York with the intention to go around the world. Now he had transited through the Panama Canal. Gerbault wore on his sleeve a passion for adventure at the edge of survival, his rail seemingly always in white foam, sailing for poetry. Pidgeon sailed as calmly as he could, and if he carried any strain of anti-establishment angst, post-traumatic stress, or a desire for thrills for art, he kept these emotions under his buttoned narrative.

Pidgeon wrote briefly of the meeting in his book, but Alain Gerbault chose not to mention it in his In Quest of the Sun (1929). Gerbault at the time was not dawdling in Panama, and surely seeing Pidgeon on the back end of his own dream must have fired his need to keep moving. The two took a photograph together on Gerbault’s boat. They both wear white shirts and trousers, but Pidgeon has on leather shoes, a tie, a cap, and, with his arm leaning against the rigging behind Gerbault, there’s the confidence of a square-jawed older brother, maybe even a teacher from church. Gerbault has his collar open, his shoes off, and he is slumped a bit. He is eager to sail to the South Pacific alone and fall in love with an ideal of Polynesian life.

Although the two never met, another solo sailing contemporary of Harry Pidgeon was Vito Dumas, an Argentinian whose why-go tilted far more strongly toward Gerbault’s passion for adventure and artistic expression. In 1931, Dumas, after attempting to swim across the English Channel, sailed a small wooden boat alone from Arcachon in southwestern France back home across the Atlantic to Buenos Aires. A decade later, in the middle of World War II, Dumas was eager to get to sea again. He, too, wrote of how Masefield’s “Sea-Fever” poem was a good expression of his feelings. At the age of forty-one Dumas sold his cattle and repurchased a boat that he had commissioned years earlier. He set out to become the first person to sail around the world by way of the Southern Ocean, along the high tempestuous latitudes known as the Roaring Forties and the Furious Fifties. With no engine, nothing electronic, nothing but wool, cotton, and leather for clothing, he sailed through the storms and towering seas common to this region of the globe. To be a sailor was to suffer, he declared. Once early on, during his first crossing from Buenos Aires toward the Cape of Good Hope, one arm became so infected and swollen and began to smell of decay, presumably because of wounds sustained while he was repairing a leak in the hull, that he thought his only option would be to amputate, at least at the elbow. After praying to Saint Teresa of Lisieux, he passed out. As he slept, the abscess burst a hole in his forearm that poured out so much pus that when he awoke he thought he had been drenched by a wave that swept into the cabin.

Le Petit Journal cover illustration of Alain Gerbault aboard Firecrest after completing his solo circumnavigation (1929).

After stops in Cape Town, Wellington, and Valparaiso, Dumas returned to the docks of Buenos Aires where throngs of people had assembled to see the man who had spent 272 days alone, almost entirely on the Southern Ocean. He was the first known single-hander to sail around Cape Horn and survive. (In 1934 the Norwegian mariner Alfon Hansen had sailed alone around Cape Horn in the other direction, but died soon after, his boat shipwrecked off the coast of Chile; Hansen, his pet dog and cat were never found.)

Over the course of his trip, which he called “the impossible voyage,” Dumas depicted a world in dramatic contrast to Pidgeon’s. The Southern Ocean weather along with the war filtered Dumas’ what-they-saw. Over the rail of his little ketch, Dumas observed submarines, warships, bombers, and in Cape Town he watched the military dead brought home by ship. In Dumas’ narrative, Alone Through the Roaring Forties (1944), the only time he spoke to a merchant ship on his voyage, the British officers aboard were unable to give him a proper position because of wartime regulations; they could only hint and wink that he was making the progress he had hoped. He depicted his voyage as a constant battle—always cold, tired, injured, and soaked to the bone. In a storm of waves over sixty feet high, half-hallucinating due to stress and lack of sleep, he envisioned himself as a man falling from scaffolding in a scene like a bombed city: “fantastic shapes of ruined buildings flickered ahead.”

When Dumas watched a shark swim under his boat he could not resist the temptation to shoot the animal in the back, yet he wrote with loving care of the seabirds in the Southern Ocean, such as his description of storm-petrels. As he watched birds soar and glide, he had moments of reflection during his unprecedented time alone. At one point, after explaining in his narrative how he never got bored, he wrote a passage as if straight out of Henry David Thoreau’s Walden (1854):

It is said that solitude is best shared with another. These seas offer joys to anyone who is capable of loving and understanding nature. Are there not people who can spend hours watching the rain as it falls? I once read somewhere that three things could never be boring: passing clouds, dancing flames and running water. They are not the only ones. I should add in the first place, work. The self-sufficient man acquires a peculiar state of mind which may be reflected in these pages.

Although he had not grown up in a fishing port or spent a lifetime as a mariner, Harry Pidgeon’s depiction of the ocean, his what-they-saw, was far closer to that of Joshua Slocum than to that of Dumas. Because he had the benefit of the Panama Canal and sailed in more temperate latitudes, Pidgeon’s sea from his peaceful platform was a setting of even less peril and contest than the voyage of Slocum’s Spray. By design, Pidgeon never had to beat his way through the Strait of Magellan or surf perilously around Cape Horn. He wrote of no dramatic storms or rogue waves, not even adverse currents or sudden squalls. Once off the Cape of Good Hope he encountered winds fierce enough that he required a storm drogue to maintain some steerage and safety—yet even of this he wrote in a tone that matches how we might complain today about having to pull over in the car because of a hard rain.

Pidgeon first came to deep-water sailing as a middle-aged man of the fields, of woods and rivers, with an eye for a photograph. He once had a job photo-documenting the large trees of California. During this trip aboard Islander he took photographs of colonies of penguins and frigatebirds. On the last leg of his circumnavigation, on the way north from Panama, Pidgeon watched two seabirds alight on his boat. He named them Blue Bill and Yellow Bill. By his descriptions and this part of the ocean, these were likely a juvenile and an adult brown booby (Sula leucogaster). Pidgeon reasonably assumed because of its dusky feathers that Blue Bill was an old bird, when it was almost certainly the opposite. The juvenile, Blue Bill, arrived first, then the adult bird, Yellow Bill, slapped its wide webbed feet aboard Islander a couple of days later. Pidgeon tried to poke them off certain parts of the boat, to reduce their droppings on his deck, but he enjoyed the birds’ company and watched their behaviors. The two birds occasionally scuffled but otherwise claimed opposite ends of the Islander. Pidgeon fed a dead flying fish to Yellow Bill by hand. Blue Bill wasn’t interested. The pair of seabirds usually left several times during the day to forage, then returned to the deck for the night. Yellow Bill, the elder, left after a couple weeks. Blue Bill stayed longer, took Yellow Bill’s spot on the aft deck, and remained a resident on Islander for nearly a month as the boat sailed on toward California.

Pidgeon ends his narrative Around the World Single-Handed in a similar tone to Slocum’s: “I avoided adventure as much as possible.”

When he returned to Los Angeles after his four-year circumnavigation, Pidgeon, like Slocum, said he had never felt healthier. “Those days were the freest and happiest of my life. The Islander is seaworthy as ever,” Pidgeon wrote, by which he meant himself, too: “and the future may find her sailing over seas as beautiful as did the past.”

Pidgeon’s Around the World Single-Handed never received the same reception as Slocum’s story, perhaps because he was the second to circumnavigate the world alone or maybe because he made it all sound too calm and boring. Pidgeon’s voyage did, however, earn a full-length feature in National Geographic magazine, loaded with his photographs, and his account had a sneakily powerful influence that propelled generations of small-boat sailors who dreamed of casting off. Pidgeon showed that it could be done, even if you were not a master mariner beforehand. Amateur sailors and boatbuilders in the 1930s and 1940s, working desk jobs or inland labor jobs, nostalgic for the days of sail and inspired by the smell of wood chips and varnish, could not see themselves quite like Slocum, but they could flip through the pages of The Rudder magazine and see the plywood design used to make the Islander and imagine themselves as a Harry Pidgeon, at anchor on their own boat in a tropical harbor of the South Pacific.

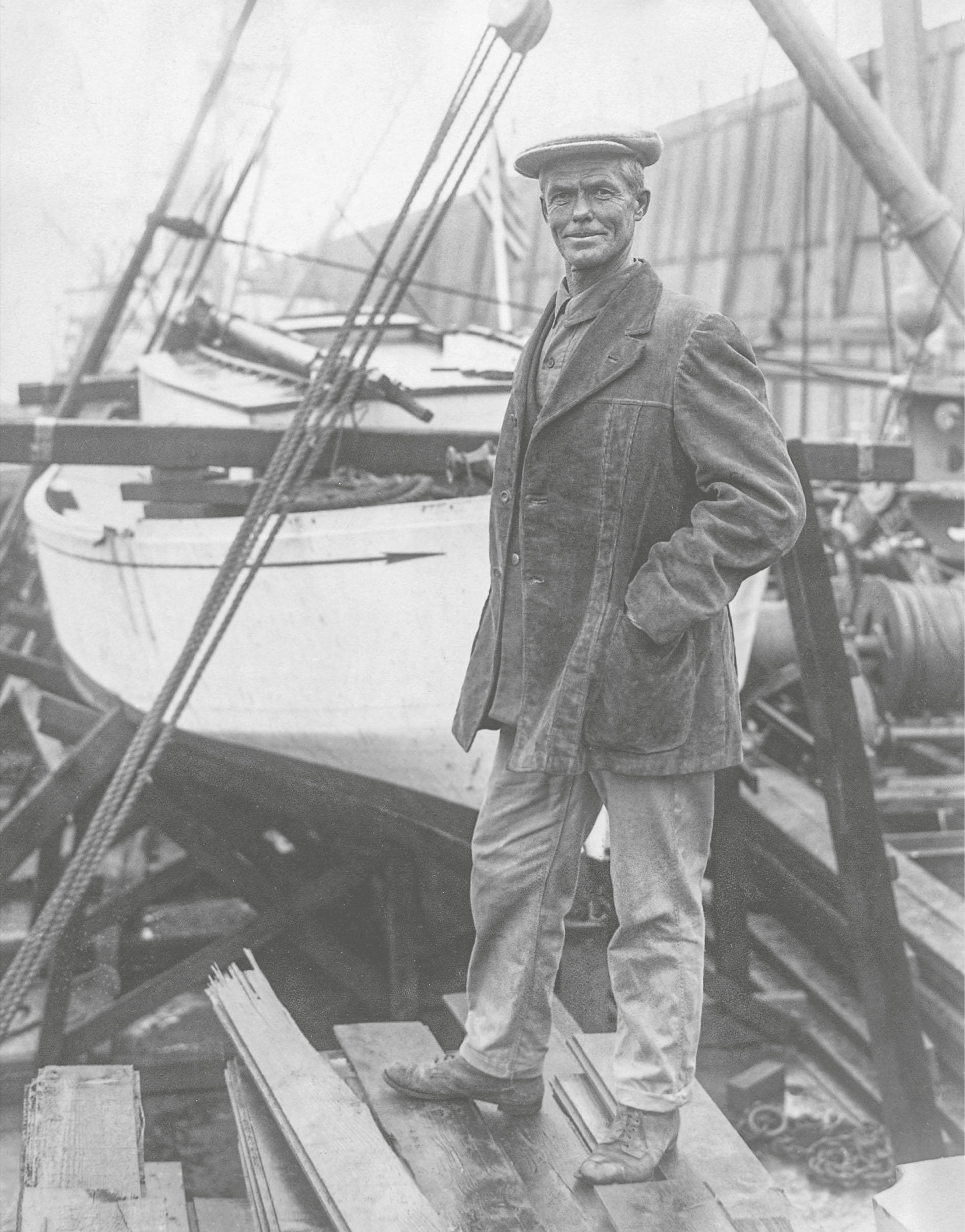

Harry Pidgeon in front of Islander, after sailing solo around the world for the first time (1926).

After Pidgeon completed a second and also uneventful entire circumnavigation, dawdling along for an extra year this time, he returned home in 1937. A sailor-writer colleague of mine named Steve Jones remembers when he was eight years old and his father rowed him out to see the Islander and the man himself in Long Island Sound. Pidgeon’s boat was anchored at the outer edge of a harbor, because the officers of the yacht club kept it out there since they thought his boat too scrappy and the sailor too lowbrow to be given an expensive dockside berth or even a mooring. Jones explained to me that they had stuck the famous sailor out to anchor in the current because he did not dress like the yachtsmen at the club, his boat “looked exactly like she had been doing what she had been doing,” and they wordlessly resented this easy-going solo circumnavigator who threatened their self-esteem and view of themselves as sailors.

At the age of seventy-four, Pidgeon married Margaret Dexter Gardner, who was twenty-five years younger. She had been born at sea, the daughter of a ship’s captain. After some time, waiting out World War II, Harry and Margaret sailed out of Los Angeles aboard Islander. At anchor at Vanuatu in the South Pacific, nearly halfway around a third circumnavigation, the boat ran aground during a hurricane and was destroyed beyond repair. Before the worst of it occurred, the two were able to climb safely ashore and unhurt with their belongings. They returned home. When Pidgeon was in his eighties they rebuilt a smaller version of Islander and made a few trips over to Catalina.

“It’s curious that this man,” assessed the French writer and sailing scholar Eric Vibart, “who preferred photographing sheep in Alaska over the frenetic search for gold, whose 19th-century simplicity echoed that of poet and philosopher Henry David Thoreau, who refused honors and the footlights, who lived in opposition to the society of greedy consumption that was coming into being before his eyes, should be so overlooked.”

But Harry Pidgeon seemed to die content at age eighty-five with what Slocum never had, a grave on dry land next to his wife, who would be laid to rest beside him years later. Pidgeon’s grave is an ordinary square-edged stone, outlined with carved leaves, sitting flush with the grass. It’s up in the hills of Los Angeles on a plot beside a cemetery road named “Ocean View.” I’ve stood there to pay my respects, looking out on the open Pacific towards Hawai‘i. Flat on the stone is a bronze plaque that reads simply:

Harry Pidgeon

Skipper of the “Islander”

1869–1954.