9. Florentino Das: For Family

Born in 1918 of Visayan descent, Florentino Resulta Das grew up in the town of Allen on the island of Samar in the Philippines, the son of a man who ran a local sixty-foot ferry. Years later, after his solo odyssey, Das told the author Nick Joaquin:

Much of what I know about the sea I learned from my father. I was already a sailor when I was still a baby, for my father and mother took me along on the parao whenever they went on a trip. I am the fourth of five children, but my other brothers have never been interested in boats. Me, I have loved them since I was a kid. Whenever my father was building a new boat, I was sure to be there beside him, even when I was very little, watching him eagerly and trying to help. My fingers are scarred from the cuts I got from knives and chisels while making my own small boats—boats that I sent sailing on the Allen beach.

Das grew up sailing with his father, marveling at his ability to predict landfalls based on the wind and the stars. He wanted to be as observant as his father, so he practiced by lying on the beach at night and tracing the stars, even tracking their distance and time using sticks in the sand.

His parents identified Florentino as being bright so they enrolled him in school, where he was doing very well, but one day when he was twelve and they were out of town he was expelled from school over an altercation with a teacher. Das was so embarrassed, afraid to face his mother, that he ran away from home with a friend. The boys made their way to working the docks of Manila, with Das working as a cabin boy on ferries and then as a stevedore. His parents tracked him down and wrote to him to come home, but he “had tasted adventure,” and he wanted to return home having accomplished something. So at sixteen, Das and another friend stowed away on an English freighter to go to America. While his friend continued on to California, Das chose to stay in Hawai‘i, which was still recovering from the Great Depression at the time. Das found work where he could, including as a professional boxer. Soon he met and married a woman named Gloria Lorita Espartino, also of Filipino ancestry, and the couple raised a family of eight children, living through the attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941 and the resulting war in the Pacific. The family did reasonably well for themselves, renting a small property. Das had a reputation as a hard-working jack-of-all-trades. He served as a fishing-boat captain, carpenter, ceramicist, and at the shipyard at Pearl Harbor. He repaired boats and cars, and his children have explained that he was a great reader, even though he never had schooling beyond the seventh grade. He loved to take his kids fishing out on the boat. At their house he kept the jaws of all the sharks he had caught, lined up from smallest to largest. At one point he sailed out, trapped, and finished off the shark believed to have been the one that killed one of his daughter’s classmates.

Yet after some twenty years in Hawai‘i, Das grew increasingly more entranced in the early 1950s with returning home to the Philippines. Not only was he finding Honolulu growing too quickly and becoming too urbanized, but his parents had been robbed and murdered back in Samar over money that he had sent home for them. He could not afford a passage by ship or plane, so he resolved to take a small boat, with the hopes of establishing a profitable fishing or ferry business in Samar and then bringing his Hawai‘i family back there, too. Das’ why-go was rooted in family and ethnic pride. Driven by poverty, one of his brothers back in Samar had turned to piracy and been killed. Florentino wanted to restore honor to the Das name. And he wanted to do something for Filipino pride internationally. He had seen what Charles Lindbergh had achieved with his solo flight non-stop from New York to Paris in 1927. Maybe he had learned, too, about historic Polynesian navigation or read about or even met Harry Pidgeon when he visited Hawai‘i, or perhaps he read about Alain Bombard or Ann Davison in Life magazine. “During the war,” Das recounted, “I was fishing captain on a boat that made expeditions to the South Seas. The navigation captain on this boat was one of the men who had sailed on a double-canoe from Hawai‘i to France, and he taught me how to read a chart and how to use a sextant.” This navigator was the French sailor and boatbuilder Éric de Bisschop, who had sailed around the Pacific, back and forth to France, and written books about his adventures.

With the help of his children over three years in his backyard, Das built a boat using a navy surplus hull. He replaced structural parts with spare timbers, added a mast and a centerboard, and scavenged parts of other vessels, resulting in a new twenty-four-foot seaworthy wooden boat with four watertight compartments. It had a self-bailing cockpit and was built so he could dog himself into the cabin in any weather. Das set up the boat with two twenty-five-horsepower outboard engines and a single mast. His project generated some local excitement and even some sponsorship from the Timarau Club of Honolulu, a group of Filipino businessmen who had done well economically. He named the boat Lady Timarau and in exchange for some start-up funds he agreed to return fifty percent of any lecture fees, book contracts, or any other profits from the adventure. The Timarau Club also offered betting odds if he would make it—all proceeds going to scholarships for Filipino students to the University of Hawai‘i.

Das’ eldest son Junior, who had helped the most with the building of the boat, wanted to join his father for the trip, which Florentino considered seriously, but in the end he was convinced it would be better for the family if he went by himself. An officer from the local US Coast Guard came and sat down with Das to dissuade him from going, explaining that he could not prevent a person going alone, but if Das took a passenger, then he said, “We need assurance that a life is not endangered through equipment or navigational preparation.” Junior could be more useful at home helping his mother with the family while Das was gone. Honolulu officials were not all doom and gloom, however. Officers at the US Navy Hydrographic Office suggested the best route for him, estimating a sailing time of forty-five to fifty-five days with stops at Johnston Island and the Marshall Islands on the way to cover the approximately 4,700-mile trip. They wanted him to clear in at Johnston, to make sure there were no new nuclear tests planned.

One of the things I’m trying to explore is why in the modern era single-handed voyaging is more often practiced and valued in wealthy, Western countries, yet not among Pacific Island or Southeast Asian communities, nor in so many of the other maritime communities around the world with millennia-long traditions of seafaring? You have to dig pretty deep to find the story of Florentino Das, and there are surely more Southeast Asian and Pacific Island single-handers that are less known. Perhaps they did not want their voyages to be publicized or maybe they were unable to publish books or articles about them. Maybe, though, there is something deeper here, crudely summarized, in terms of social values in modern Pacific Island cultures: an emphasis on family, serving the community, and decentering the individual? Maybe, for mariners in some communities over the last two centuries, to go off alone would be to shirk your filial and local responsibilities?

Maybe there could be something, too, in the overly simplistic, perhaps unfair generalization that non-Western, non-white cultures tend to value collective adaptation over individual manipulation. The social-science researcher Peter Belmi, a Filipino immigrant and professor in the business program at the University of Virginia, has found that people from wealthier backgrounds end up focusing more on themselves, whereas people from communities with fewer resources seek power or success to benefit others, since they have been raised relying on their communities to survive. “We don’t need others as much in order to survive,” said Belmi, referring to the thinking of those in power, “and so what it means to be a good person is to pursue your own identity, to figure out how you are unique, compared to others.”

Larry Raigetal, a master boatbuilder and navigator from Yap in Micronesia, put it this way in 2021: “The day you are born until the day you die, you are to give back to the community.”

“In the year of our Lord, 1955—departed Kewalo Basin, Honolulu, May 14, Saturday, with the blessings from family, friends, and the good people of Honolulu, that I may reach my destination, the Philippines, swiftly and safely.”

So wrote Florentino Das in his journal, which was later published in six instalments in the Honolulu Star-Bulletin (which said he wrote like a modern-day Robinson Crusoe). Das departed with letters from the mayor of Honolulu and the governor of Hawai‘i that were addressed on his behalf to the mayor of Manila and to the president of the Philippines. The docks were crowded with people, photographers, and journalists. A reverend blessed the voyage, a six-piece band played, and he sailed away wearing multiple leis around his neck. At a later stop he would paint “Spirit of Hawaii Filipinos Aloha” on the port and starboard rail. He was thirty-seven years old.

The first days did not start auspiciously. His main boom broke only a couple of hours out of the harbor. He was able to replace this with an oar. As he caught up on sleep from the last three weeks of dashing around to get ready, he realized he had forgotten some key parts for his outboards. He had also forgotten a mirror, “sunburn oil,” a sea anchor, a regular anchor, nets for fishing, and spare batteries for his radio—for which he depended on the time signal for navigation and from which he planned to get weather reports, news, and music for company. Regardless, each morning he began with prayer. He decided that going back at this point to get those supplies would send the wrong message; he did not want to seem afraid.

In early rough weather, Das wrote that he was “shaken like a dice in a cup.” He wished he had a hammock. The darkness of the early nights out at sea reminded him of the wartime blackouts in Hawai‘i. His Lady Timarau held up, though, which gave him confidence. He caught a large male dolphinfish, but the leader snapped, and he lost the fish and his lure before he could get the animal on board.

Soon Das began to settle in, ever westbound. He had a sextant, a compass, two watches, and he knew the stars well. He was handy working on his engines, which needed constant maintenance due to the waves and spray. He had a mainsail, a staysail, and it appears he used a lateen rig with parachute material, setting this like a spinnaker for sailing in light air downwind. He had a small stove to make coffee and to warm the canned food, of which he had packed supplies to last him ninety days. He had loaded thirty-five gallons of water, four gallons of wine, four quarts of whiskey, and 150 gallons of gasoline. He had a motorcycle stored in the hold for when he reached the Philippines.

A friend had given him a safety helmet, which he was actually wearing one day while taking a sextant sight. His foot was on the tiller easing the boat over, so he could get the sun in view, when the boom swung across and bashed him on the back of his head, knocking him to the deck and sending the helmet into the water. Das figured that the helmet had saved his voyage, if not his life. He resolved to always use a boom preventer from now on.

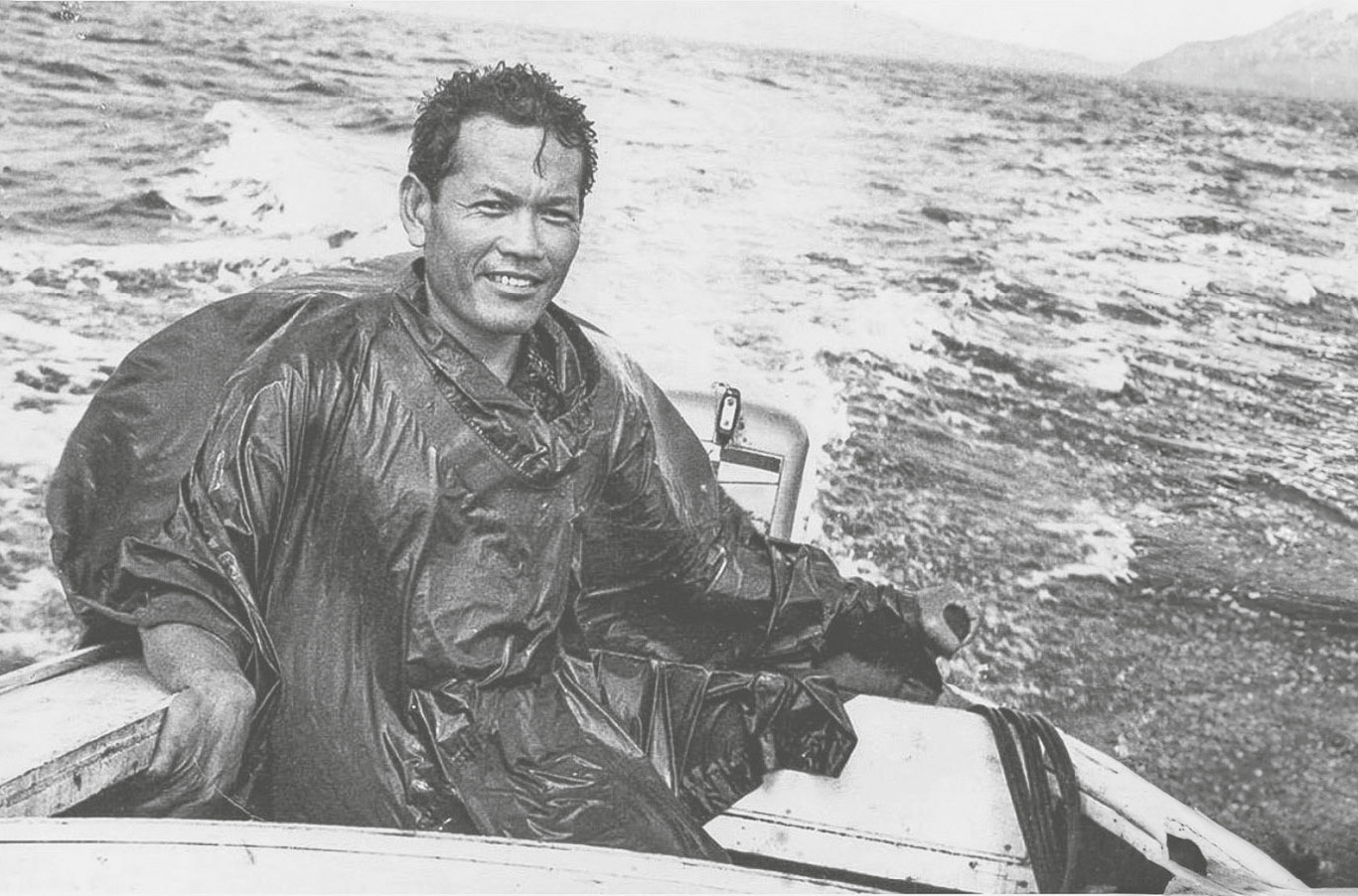

Das driving the outboard engine on his boat in Manila (c. 1957). He sent this photograph to his oldest daughter Louisa, with a note on the back, which included: “I’ll always love you and the rest of your brothers and sisters for as long as I live and even beyond.”

“I happened to think of my wife and children and felt so lonesome,” he wrote on the ninth day out. “Wondering how they are. If they only know what their daddy is going through. Out here, with only the skies and the horizons around you, you feel so lost. I never feel lonely before in all my life till only now. You never know how much I prayed to the good Lord, to bring me carefully and safely to my destination.”

Without a method of self-steering, Das became terribly sleep-deprived. He hung a rosary above the tiller, “with the hope that the Almighty will take care of the boat and me while I go to sleep.”

Das continued west, watching the sky for Hawai‘i-bound aircraft to confirm his bearings. He took angles on the sun, its height above the horizon, and used his compass. On one day of high seas a jar in his cabin tumbled over and broke. He accidentally stepped on it with his bare feet, then had to use his knife to cut into his skin to remove the glass. Although the sea was rough, the winds had been largely favorable, yet there had not yet been as much rain as he had expected in order to resupply his drinking water and take a proper shower. He was finally able to land dolphinfish, some of which he ate and some he dried for eating later. In calms, he constructed a higher bracket for the motors, because they were getting too wet when not in use. He rebuilt one of the ignitions. One watch, which he had set to Greenwich Mean Time for his celestial navigation, stopped, but he still felt he had a reasonable sense of where he was, so he decided to steer north of west, to stay above the Marshall Islands, since he did not trust his motors if he ended up being blown onto the reefs. As his fresh food ran out, he ate canned kidney beans, canned mangoes, and with his dried fish he often ate poi, a traditional Hawaiian paste made from taro root.

As the winds continued to blow favorably, Das got the idea to rig up an old car radio that he had aboard to his battery. He managed to make this work, using the mast stays as an antenna. Sixteen days out from Oahu he tuned in to a radio station from Japan, then one from Hawai‘i, from which he was able to reset his watch on their time signal and calculate his local time and his longitude. Das and Lady Timarau had sailed 1,350 miles. Ever since he had left, his boat had been leaking around the centerboard trunk, requiring regular repairs to his bilge pump to keep ahead of it. Fair winds continued, though, and he finally figured out a system of how to get the boat to steer itself. Once while sitting down with a can of chilli con carne, he caught two more large dolphinfish in a matter of minutes. All was well.

The short on-board journal of Florentino Das that he sent in to the newspaper finishes about there. His final published entry, on 3 June 1955, ends: “I have been a good boy all my life, so I guess the good Lord will not leave me in the lurch. I am not a bit worried. I know somehow, that the good Lord is watching over me. For all these things that is happening, he must have some reason. I dare not question His decision.”

While Florentino Das was traveling alone, sailing for his family and for Filipino pride, for the legacy of his name and the stories his children could tell their descendants, Western stories about Pacific Islander relationships to the sea were growing in popularity, which would in turn continue to influence sailors from around the world to go out to sea—as well as how people saw themselves out there alone.

For example, in 1940 an American writer and illustrator named Armstrong Sperry created a young adult novel titled Call It Courage. This became a bestseller in the United States, was given the Newbery Medal for children’s literature, and was soon taught in schools and read by millions of early teenagers. Call It Courage remained a mainstay in American school curricula up into the 1990s. The story is about a fictional teenager, Mafatu, who lives on the island atoll of Hikueru in the Tuamotus. The son of the chief, Mafatu, is ostracized by his community because he is afraid of the ocean—the sounds, the animals, the act of fishing—a terror that began when as a toddler he and his mother were swept out to sea. His mother saved him, kept him alive out at sea all night, but after managing eventually to float him to safety on the beach, she died of exhaustion. Years later, life with this fear of the ocean becomes so unbearable and shameful that Mafatu steals out in a boat alone with the why-go to conquer his personal horrors and make his father proud. He sails out past the reef with his pet dog and an albatross flying above. Mafatu finds another island, where he shipwrecks, losing his boat to the coral on the way in. On this new island he is forced to slowly build his confidence and his self-sufficiency. He fishes for his food. He kills a large shark. Then he slays a large octopus. He makes tools out of whale bones, constructs a new boat, and launches it by himself, sailing out toward the barrier reef: “The reef thunder no longer filled Mafatu with unease. He had lived too close to it these past weeks. Out here, half a mile from shore, detached from all security of the land, he had come to believe that at last he had established a truce with Moana, the Sea God. His skill against the ocean’s might.”

Mafatu has a mastery of the sea now, but he recognizes a personified ocean of which full knowledge is impossible and safe passage requires utmost preparation—and also luck, appeasement, and blessings. On the way home, his dog and albatross with him, Mafatu barely manages to escape the “black eaters-of-men” who chase after him in six “black canoes.” He survives by endurance, his sailing skills, and the blessing of Moana, a male ocean deity who gives him enough of a breeze at the crucial moment to escape the cannibals. Mafatu finds his way home with the help of the stars, knowledge of the currents, and the albatross. On his return, his father recognizes his son’s courage and Mafatu collapses on the beach. His voyage and heroic return will now be fixed in the chants and stories of his island.

Less than a decade after the publication of Call It Courage and a few years before the voyage of Florentino Das, the cultural theorist Joseph Campbell published his seminal study of myth and heroism, The Hero with a Thousand Faces (1949), which outlines an archetypal storyline that has existed across cultures and across millennia. It goes like this: there is an isolated hero who is different in some way and forced to leave home for some reason, going on a vision-quest by choice or by force; the hero finds a friend or two along the journey, conquers his fears, slays a dragon or two (or some equivalent); the hero then returns home a changed, wiser, more mature person, bringing something new or significant to his community. “You leave the world that you’re in and go into a depth or into a distance or up to a height,” wrote Campbell. “There you come to what was missing in your consciousness in the world you formerly inhabited.” From here you return home with “that boon.” Campbell identifies this mythical story structure in various forms in cultures all around the world and in humanity’s major religions, such as Moses climbing Mt Sinai, Buddha sitting in solitude under the bo tree, and Jesus off in the desert alone for forty days.

Call It Courage fits right into this universal hero’s journey story structure, which has been embraced in so many modern Western stories. You can see it in epics like Star Wars and Harry Potter. Fitting particularly well into Campbell’s hero’s journey, too, is the sea story, especially that of the single-handed sailor—both on paper and in that person’s perception of their own experience, their voyage on Earth. Call It Courage is a Western story using Pacific Island characters, but if Campbell is right then maybe this rare need to adventure alone for physical trial in environments distant from human influence is a desire intrinsic to certain people everywhere and has been always? In the 1960s historian and writer J. R. L. Anderson argued the universality of the need, even the genetic selection in certain individuals, to strive for this sort of adventure, what he called the “Ulysses Factor.”

With all this in mind, did Florentino Das see himself in these terms when he was out there, getting thrown around inside his cabin among big seas? Did he see himself as a conquering hero who sought challenge and wisdom, returning with a boon to share when he returned home?

On 19 June 1955, Das signaled a passing Japanese fishing boat with a foghorn and by raising and lowering his upside-down American flag, showed he was in distress. The Lady Timarau’s engines were now entirely out of commission and his hull was leaking so badly that he was having to pump continuously. The captain of the Daisan Shinsei Maru No. 3 agreed to tow Florentino Das for about 500 miles, for three days, to a harbor on the island of Pohnpei in Micronesia, which was in the direction they were heading anyway.

Safely ashore on Pohnpei, Das wrote to his wife in Hawai‘i about how much he loved her, how much he missed her and the children, how he felt like a championship prize-fighter who had been knocked out for a round. When word got back to his sponsors in Hawai‘i with his request for money for repairs, some tried to raise funds, while others, including the Philippine Consulate in Hawai‘i, asked him to abandon the voyage. Das felt obligated to continue. He said in a radio interview at the time that he had been away from home for so long already, and that more than the voyage was at stake at that point. “The world was waiting how I would fare,” he said. “I wanted to prove that Filipinos are not only good boxers but also good boat builders and sailors.”

Das spent eight months in Pohnpei, repairing his boat and waiting out the typhoon season. Then he continued on, his departure making international news. During the second half of his voyage, over 2,000 more miles, Das stopped in the Chuuk Islands in Micronesia for a couple of weeks. On his way to his next landfall, a passage of several hundred more miles, he decided to do some fishing for sharks. He later explained that he sailed into a school of sharks that were about eight feet long: “Whenever they grabbed my line, I would pull them in, kill them with my knife and take my hook out. Sometimes I cut off their fins. Late in the afternoon, I hooked a really monstrous shark—about twelve feet long—and it almost dragged me into the water and I hurt my leg in the struggle to save myself. I cut my line and let the shark go. My leg was badly bruised. I was limping when I arrived in Yap.”

He stayed in Yap for a few weeks, then made his final approach to the Philippines. He managed to scoot south away from the path of Typhoon Thelma, but still he and Lady Timarau were battered by winds and seas until, knowing he had neared land because of the approach of dolphins, Das arrived safely on a beach at Siargao Island on 25 April 1956, completing a 346-day odyssey since he had left Honolulu.

Das continued on to his home in Samar, reuniting with his siblings and extended family. From here he was escorted by the Philippine Navy and Coast Guard to Manila, where he was paraded around, met by President Ramon Magsaysay, and celebrated as a hero throughout the country. The local newspapers declared his voyage more significant than Heyerdahl’s Kon-Tiki. He was awarded the Legion of Honor, named an honorary Commodore of the Philippine Navy, and he was given the keys to the City of Manila. Back in Hawai‘i there was a large banquet for his wife, Gloria, who was named “Mother of the Year” and presented with formal gifts from several local societies and clubs. A fund was set up to raise money to send the whole family to Manila to be with their father.

Florentino Das never claimed to be, nor did it seem that he thought of himself as a master navigator in any traditional sense, like the early wayfinders, but he did safely sail across a massive swath of the central Pacific, the length of more than one and a half trans-Atlantic crossings, in a boat he built from scrap—with no electronics, extraordinary ingenuity and grit, and a great deal of faith in himself and a higher power.

The celebrations of Florentino Das in the Philippines fizzled out far too quickly. Das was never able to gain any financial footing. The fund in Hawai‘i to bring his family over never raised enough to send the entire family. Gloria, understandably, would only go if she could bring all the children. Das struggled to find money at his end, even enough to fly when he decided he would try to go back to Oahu to be with them. He even toyed with the idea of sailing back to Honolulu in Lady Timarau. A fishing or ferry business never got going. At first he worked as a shipyard caretaker, then at the Philippine tourism and travel agency, since his English was so good. But this also did not earn him enough to get himself back to Hawai‘i. In 1957, Gloria requested a divorce so she could remarry and have someone to help raise the children. He agreed.

In 1962, after doing some tourist sails and some survey work with Lady Timarau, his boat sank at the dock during a typhoon. He had no money to raise the boat himself. Das had recently remarried himself, to a widowed school principal with four children of her own, but he remained poor, and he began to lose his eyesight from complications of diabetes and high blood pressure. He was unable to work. Until he was completely blind, he wrote regular letters and called his children on the phone when he could afford it. Recent interviews with the Das children reveal that they never felt abandoned by their father, that he so clearly loved them always and deeply. Das’ new wife kept up the correspondence with his children in Hawai‘i. In 1964, at only forty-six years old, he died of organ failure in a hospital in Manila.

Florentino R. Das left no autobiography other than the as-told-to story by journalist Nick Joaquin and the short at-sea entries published in the Honolulu Star-Bulletin. His original journal is lost. We have no further record of his observations and thoughts on birds, marine mammals, the sea more specifically, his what-they-saw of his voyage. Largely due to efforts beginning in the 1980s, however, there are now two monuments to his voyage in the Philippines; one plaque in Honolulu; and at the Philippine Consulate in Hawai‘i, after a group sent an unsuccessful delegation to try to recover the boat, is a scale model of Lady Timarau on display. The day of Das’ arrival is now celebrated each year as “Lone Voyagers Day” on Siargao Island. A loving biography, Bold Dream, Uncommon Valor: The Florentino Das Story, was published in 2013, and it is filled with color photographs of his descendants and crafted as a book for schools, with each chapter ending with reflective questions and activities with the intention that Das’ story will build Filipino pride, identity, values, and encourage students to “take social action.” The authors explain that the heroism of his solo voyage is “by all means, a personal success, a fulfillment of a personal dream. But it was also an achievement of a people and, most of all, a triumph of faith and the human spirit.”

In his argument for including this solo sailing story in school curricula, as well as the importance of properly maintaining and interpreting the monuments to the voyage, Professor Jonas Robert L. Miranda explained in 2014: “Florentino Das’ entire life epitomizes the ambivalent nature of Filipino values. His undaunting spirit to begin the unthinkable journey can only be understood by considering the paradigm regarding Filipino values of Bahala na and Love for Family.”