15. Bernard Moitessier and a Sea of Spiritual Solitude

As Horie and Adams were crossing the North Pacific in the 1960s, still more people around the world were setting out alone in their own small boats to cruise across oceans. They set out with a cabin bookshelf that reverentially held a well-worn copy of Slocum’s Sailing Alone Around the World and a growing library of other single-handed sea stories. They flipped though the articles about teenager Robin Lee Graham and Dove in National Geographic and read technical developments about small engines or rolling furl systems in magazines such as The Rudder or Yachting. As their little home heeled and proudly passed over the waves, the bindings of the books and magazines they carried clicked against the wooden fiddles that were slotted across the shelves so the volumes didn’t tumble out into the cabin. Some people set sail in their boats primarily to challenge themselves or to escape constricting personal circumstances or to flee choking post-war modernity or materialism. Others went to sea primarily for the dream of slurping fresh mangoes and snorkeling off their floating house in warm, turquoise water. Still others chased a vision of gazing up at the Milky Way as their cozy little craft glided gently through blue-green bioluminescence.

The blossoming number of small-boat voyages in the 1960s was enabled by advances in self-steering devices, improved electronics, and technologies developed initially for the military that made navigation and communication at sea safer and easier. Boat designers continued to experiment with multihulls, constructing with materials like fiberglass, aluminum, steel, and even cement, building the vessels more cheaply, while also aiming for more stability, speed, and better abilities to sail closer to the direction of the wind. (A “monohull” means just that, one hull, a traditional Western boat; i.e. not a catamaran or trimaran, called a “multihull,” which had been perfected, likely invented, by Pacific cultures centuries earlier. Catamarans and trimarans almost always sail faster, but usually far less safely if pushed to maximum speed.)

A further spark for the expansion of small-boat cruising was the reintroduction of solo races across oceans, reignited some seventy years after the first stunts across the Atlantic by Si Lawlor and William Andrews in the 1890s. For the first public race of this new era, five middle-aged men in 1960 sailed alone from Plymouth, England, over to New York City, aiming across a route largely against the prevailing winds. They convinced the Observer newspaper to sponsor them, so it was first known as the Observer Singlehanded Transatlantic Race, or the OSTAR, which has continued roughly every four years since with a variety of sponsors and different names.

This organized, competitive racing alone under sail across the Atlantic Ocean, along with voyages like Horie’s and Adams’ across the North Pacific, and the enduring legacy of Slocum, Pidgeon, Gerbault, Dumas, Davison, and others, led to the ultimate challenge of sailing alone around the world non-stop, a voyage of nearly a full year alone without stepping on land or even anchoring. The first of these non-stop circumnavigation races in 1968 thrust into the Western imagination a court of truly extraordinary and varied characters. Perhaps the most remarkable was a French sailor named Bernard Moitessier. An explorer-hippy-poet of the sea, Moitessier was a generationally unique blend of Edmund Hillary, Henry David Thoreau, John Lennon, and Jacques Cousteau: a spiritual, ocean-adoring anti-capitalist who had endless energy and we-can-change-the-world aspirations. He and a British sailor named Robin Knox-Johnston accomplished, and I mean this without hyperbole, one of the most astounding and difficult individual feats of physical and mental endurance and skill in modern history. Moitessier returned to shore after his voyage to then craft a work of transcendent sea literature, a narrative of nature writing delivered from a deep-ocean physical and emotional space that few humans have or will ever visit.

Bernard Moitessier published his first book, Vagabond des mers du sud (Vagabond of the Southern Seas, published in English as Sailing to the Reefs) in 1959. This was a memoir about his youthful sailing adventures. A bestseller in France, the book earned him enough money and inspired enough fame and generosity from others to commission the construction of a tank-tough ketch made of steel, which he painted bright red and named Joshua, after Slocum. Moitessier used this bare-bones vessel as a sailing school for a couple of years in the coastal Atlantic and the Mediterranean. In 1963, the year after Horie’s trans-Pacific crossing, Moitessier and his wife Françoise sailed from France to the South Pacific via the Panama Canal, leaving behind their three young children in boarding schools and with family. They returned around Cape Horn and back up to Europe, not only weathering a six-day trial of hurricane-force winds and seas in the Southern Ocean, but also, in part due to their haste to get back to see the children, setting a new record at the time for the longest-known non-stop voyage in a small sailboat, landing in Spain after cruising over 14,200 miles in 126 days.

Meanwhile, the first OSTAR race had been completed. Of the five competitors, in third place was Dr. David Lewis, who would go on to research traditional Pacific navigation and sail alone to Antarctica. In second place was an English war veteran named Blondie Hasler, who had organized the race and would become influential in single-handed boat design, including inventing a popular self-steering servo-pendulum device. The winner of this first OSTAR in 1960 was Francis Chichester, the oldest among them and the owner of that wind vane he designed and called Miranda. To put Bernard Moitessier in context, it’s necessary to tack over for a bit to learn about Chichester.

By 1960, Francis Chichester had thick bottle glasses, large ears, and was nearly bald. Born in 1901, the year after the publication of Slocum’s Sailing Alone Around the World, Chichester was raised in a church rectory. Beginning at the age of six, he attended British boarding schools. After shipping out to the then British dominion of New Zealand at eighteen, he made his fortune there in the business of lumber and other natural resources. Chichester’s fascination with solitary adventure began with airplanes. He flew small aircraft alone across oceans in the pursuit of various firsts, some successful, others nearly so. One solo crash nearly killed him. By the time Britain’s involvement in World War II became inevitable, he was too old and his eyesight too poor to be an active pilot, so he served as an instructor. After the war, as his fellow-pilot Ann Davison was sailing across the Atlantic in Felicity Ann, Chichester and his wife Sheila started a cartography business, writing books on navigation and aircraft. It was around this time that Chichester got seriously interested in sailboats.

After winning that first OSTAR with a passage of forty days, Chichester sailed back across with his wife Sheila and designed a new boat for the next OSTAR in 1964. This time he came in second, now among fourteen participants. Over this time he wrote three sailing memoirs, but growing older (now sixty-four) he wanted a still bigger challenge. In September of 1966, after over two years of preparation and with a custom-designed boat, he set out to sail around the world with only one stop. He sailed eastbound by way of the big westerly winds and waves of the Southern Ocean, steering around the three big, famous, scary capes—the Cape of Good Hope at the edge of South Africa, Cape Leeuwin at the corner of Western Australia, and then around the most notorious, Cape Horn at the tip of South America. Not including a six-week refit in Sydney, he did this all in a bone-weary nine months and one day. The guiding idea was that he was recalling the clipper-ship runs that carried bulk cargo, such as wool or grain, the last of which were underway in Harry Pidgeon’s time. Chichester ceremoniously departed from London, near the berth of the record-setting square-rigger Cutty Sark, replicating the trip of the clippers down the Thames before he departed from Plymouth. During all his preparations Chichester managed to publish an annotated anthology titled Along the Clipper Way (1966), which included a selection from Davison’s My Ship Is So Small.

This historical tap into the nostalgia of the clipper ships provided context and motivation for another expedition and another first. In his best-selling narrative of his one-stop circumnavigation, Gipsy Moth Circles the World (1967)—the book that ends with the number of words written in his logbooks—Chichester’s explanation for his why-go (which is in the first chapter, as nearly all the solo stories of this era begin) is about achievement and the records remaining.

Chichester gave two major reasons for this solo trip. His first was that he wanted to sail single-handed around Cape Horn. Slocum, for example, had chosen the Strait of Magellan, because sailing around open Cape Horn, just to the south, seemed just too dangerous for Spray. “I told myself for a long time that anyone who tried to round the Horn in a small yacht must be crazy,” Chichester wrote. “Of the eight yachts I knew to have attempted it, six had been capsized or somersaulted, before, during or after the passage. I hate being frightened, but, even more, I detest being prevented by fright. At the same time the Horn had a fearsome fascination, and it offered one of the greatest challenges left in the world.” Chichester explained in his narrative, as an aside, that one other small boat had made it around Cape Horn that he did not know about before he left. This was the voyage undertaken by Bernard and Françoise Moitessier aboard Joshua. They had arrived home in Europe only a few months before Chichester left England, and Chichester was halfway around the world by the time Moitessier actually published his account, his second book, Cap Horn à la Voile (Cape Horn: The Logical Route, 1967).

Chichester’s second why-go was simply about speed, believing he could set the record for the fastest solo circumnavigation and compare a modern yacht’s run to that of the big ships of old. He accomplished both of these goals, the fastest single-handed circumnavigation by far and a passage safely around Cape Horn. In the process, Chichester set a half dozen other more specific speed records, such as the farthest week’s run for a solo sailor, and he more than doubled the miles previously traveled by a single-hander without stopping in port.

The voyage from the start was a high-profile, big-budget, public event. Chichester became a national hero. An airplane of journalists and a Royal Navy ice-patrol ship photographed him off Cape Horn in the Sir Francis Drake passage. As he began the homeward-bound trip north in the Atlantic, other planes and ships were dispatched to view him, reporting on his progress. On the return to the English Channel in May of 1967, a flotilla of personal and official boats and five large naval ships came out to escort the solo yachtsman back into Plymouth and to a quarter of a million people lining the docks. It was covered on the radio, on television, and on the front of the newspapers. He was knighted by Queen Elizabeth II with the same sword that the first Queen Elizabeth had held to knight Sir Francis Drake, 386 years earlier. The English public seized upon the person and the idea of Sir Francis Chichester, a man arriving home when the country felt spiritually and economically depressed in the wake of the convulsive loss of its empire around the world. Chichester provided a throwback sort of heroism, especially for a sector of the British populace that could not quite feel the same patriotic pride about the Beatles or even from the more Tory fictional heroisms of James Bond. Chichester’s solo circumnavigation, while most men his age were comparing pruning shears with their neighbors, managed to strike a cultural nerve. He inspired millions of people in Britain, as well as around the world.

Sir Francis Chichester waves to the crowds while raising a commemorative medallion of Gipsy Moth IV given to him by the Lord Mayor of London (1967).

Chichester loved his country and his queen. All clean shaves and collared shirts, he presented himself as a man of precision, decimals, half-degrees, and careful record-keeping, yet he still had time for a cocktail or a beer. He loved his wife and his tea and his toast. In his writings and radio dispatches from the boat, he kept his emotions to himself. In Gipsy Moth Circles the World he recounted all his setbacks with “it could have been worse,” revealing only low points that feel performed, such as when he quotes from his own journal as he celebrated his wedding anniversary alone: “A very remarkable exceptional woman is Sheila. I did what is supposed to be un-British, shed a tear. Life seems such a slender thread in these circumstances here, and they make one see the true values in life.”

Chichester spent most of the narrative of his monumental voyage talking about his yacht, Gipsy Moth IV, which he hated because it was too large and in many ways all wrong for the job. Yet he made it work against all odds. He described how much he disliked having to think about a motor at all on a sailboat. In his era before solar panels or wind generators, he needed his motor to work for a few hours now and again to charge his batteries. He managed to keep it chugging along thanks to his clever repairs, scrunching his body and bracing himself upside down in rough seas with tools in his teeth. In other words, Chichester presented his trip around the world as a series of technical challenges to be overcome by intellect, proper preparation, and moral fortitude.

Like Davison, his descriptions of marine life seem almost obligatory, to give his reader a sense of the different locales at sea. His flying-fish breakfasts were often detailed. He offered an intriguing account of albatross cries sounding like human screams. At another point he approached a poetic moment when a storm-petrel landed on deck. The tiny bird offered a touch of soft warmth, something alive after months of only cold on the inanimate boat, but Chichester quickly pulled back from this emotional connection in his prose. The bird died the next day.

Another small telling moment revealed how driven Chichester was by competition, by records, by an English boarding-school childhood, which even shaped his relationship with what-he-saw in these lonely open-water spaces. Of his outbound passage in the South Atlantic, he wrote: “Those rainless days had compensations, for they were mostly pleasant weather, with clear skies and calm seas . . . I saw lots of birds, and always enjoyed watching them. I appointed myself a judge at a birds’ sports day, and awarded first prize for graceful flight to the Cape Pigeons.”

A full generation younger than Chichester, Bernard Moitessier was born in 1925 in French-colonial Vietnam, then known as Indochina, the oldest of five children. His parents were French, his father a successful businessman, his mother an artist. Bernard grew up in French schools, and when young had an influential nurse of Chinese descent whose teachings stuck with him. His childhood in Saigon was rural and coastal enough that he spent much of his time in the rainforests and along the coasts, where he first learned how to fish and sail a boat. He spoke Vietnamese fluently.

Toward the end of World War II, the invading Japanese military imprisoned French expats. After Hiroshima, with his father imprisoned because he was a reserve officer, Bernard, now aged twenty, brazenly flew the French flag out of their apartment window. This got his family all thrown in jail. Moitessier often recounted the time when a soldier came into his cell intending to kill him, but with a wordless exchange of eyes, the Japanese man decided to lower his gun and walk back out. It was a moment that would stick with Moitessier for the rest of his life, sowing his distaste for killing anything if not for food, even rats.

After he and his family were released, amidst bloody conflicts between communists and French colonizers, Moitessier (and his two brothers) joined a volunteer anti-communist military patrol, serving on a gunboat as an armed seaman and interpreter. One day when Moitessier’s brother, Françou, was on a different patrol, he gunned down a man who had once been their close friend as children. A few days later, tortured by remorse, Françou killed himself.

When these conflicts cooled, still mourning for his brother, Moitessier tried to work for his father, but then decided to return to the water, working a business under sail on the Gulf of Siam, delivering rice and returning with wood or sugar. This lasted six months, until he was accused of smuggling arms. So he went to France and hitchhiked and biked around Europe for a while. This was not satisfying, either. He took a ship home to Saigon.

Now in his mid-twenties, Moitessier, with his thin beak nose and sharp chin, began his voyaging years by sailing off with a friend to Singapore and back in a roughly built boat. Moitessier then purchased another old wooden sailboat, which he named the Marie Thérèse after a woman he loved but to whom he could not commit. Moitessier departed alone westbound through Indonesia and the gulfs of Siam and Bengal until he ran hard aground on the coral reefs of the Chagos Bank in the Indian Ocean. The boat was lost. By other means he made it to Madagascar where he spent a couple of years building a new boat, which he later sailed across the Atlantic and then wrecked in the Caribbean. All of these events proved fodder for that first book in France that earned him, perhaps ironically, the supporters and money to build a new boat.

Moitessier loved his steel boat Joshua and the trials with his wife Françoise on their sail to the Southern Ocean and around Cape Horn. But he loathed Cap Horn à la Voile, the book he wrote about the voyage. He had allowed himself to be pressured, to write it too quickly to meet his publisher’s desire to get it printed before a big boat show. This sense of creating a rushed, poor piece of work slumped Moitessier into a depression. Back living a domestic life in France, pacing the streets like a Byron, an Ishmael, a Paul Gauguin, he devolved to near madness, according to his biographer and friend Jean-Michel Barrault. Moitessier felt trapped, self-loathing, and he still mourned the tragedy of his brother.

Moitessier wrote later that the idea of a new book, one of true quality and sincerity, and the idea to circumnavigate the Earth aboard Joshua alone without a single port stop, came to him in a eureka moment as one glorious thing together with the why-go desire to create a work of literary art:

I must have been on the point of suicide when the Child hurled the lightning bolt that paralyzed the Monster. In one blinding flash, an entire part of my future appeared before my eyes, and I saw how I could redeem myself. Since I had been a traitor by knocking off my book, what I had to do was write another one to erase the first and lift that curse weighing on my soul.

A fresh, brand-new book about a new journey . . . a gigantic passage . . .

Drunk with joy, full of life, I was flying among the stars now. Together, my heart and hands held the only solution, and it was so luminous, so obvious, so enormous, too, that it became transcendent: a non-stop sail around the world by the three capes!

This was toward the end of 1967, only a few months after the knighting of Sir Francis.

Even before Chichester completed his one-stop circumnavigation via the three capes, others besides Moitessier were fantasizing and even planning a non-stop world voyage, what now seemed the remaining pinnacle of sailing alone. Getting wind of these disparate plans and wanting to get in on the publicity in the wake of Chichester’s phenomenal success, staff at the Sunday Times newspaper in London conjured up the Golden Globe race. Within a given set of dates for departure, they would award a prize for the first person home and then another prize for the fastest time. Although the captain need not enter the race officially and no trials or inspections were necessary, a representative from the newspaper did go to France to speak with Moitessier, in the hopes that he would enter. Disdainfully, Moitessier agreed to sail out of Plymouth to be a part of the race, but he would not be sponsored nor would he take a radio to send updates. He told the newspaper and race committee that if he won he would take the money without a thank you.

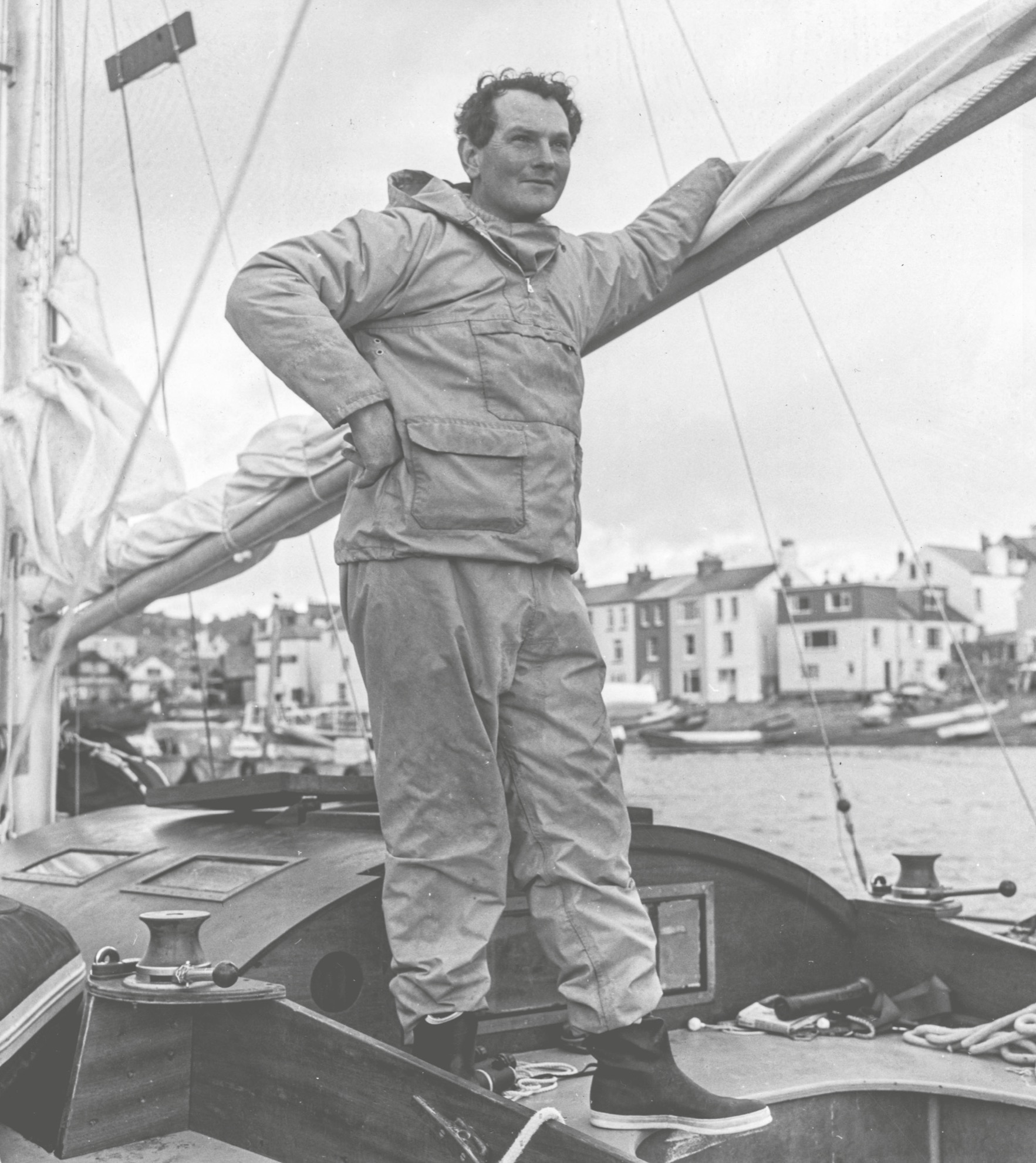

Between June and October of 1968 nine men sailed out of the ports of England and Ireland, choosing their time to leave based on their readiness, personal schedules, and own strategies as to the best projected weather to round the three capes. Of these men, only one, a young English merchant mariner named Robin Knox-Johnston, completed the voyage. Like the proverbial tortoise beating the hare, through seamanship, preparation, experience, and sheer grit, he sailed home triumphantly in his rust-streaked, copper-patched wooden boat after 312 days at sea. Although forty years younger, Knox-Johnston was forged out of a similar patriotic English mold as Chichester. He too received a national welcome as he stepped back on to the stone quay, bearded and bedraggled but beaming from ear to ear.

Robin Knox-Johnston returning home, just off the Isles of Scilly, aboard his 32-foot boat Suahili, as the first person to sail alone around the world without a single port stop (1969).

Of the other seven entrants, leaving Moitessier aside for now, five were unable to sail beyond the Cape of Good Hope, dropping out at different distances due to some variation of gear failure and bad weather. Some of them had departed in small fiberglass boats that simply were not built for a world voyage like this. Nigel Tetley, a British lieutenant commander who grew up in South Africa, competed in his cruising trimaran and managed to pass the three capes, circumnavigate the world, and come within a couple weeks of arriving home in Plymouth with a far faster time than Knox-Johnston—but his boat broke up underneath him in heavy weather off the Azores. Tetley was pushing his vessel too hard to try to better the voyage of an English electronics engineer named Donald Crowhurst, who apparently also was making excellent speed himself in a similar trimaran. Tetley’s boat sank. He had to be rescued from his life raft.

The tragic, stranger-than-fiction irony of this was that Crowhurst, suffering early structural failure of his boat and a chaotic lack of preparation, had been so afraid of the shame and the financial ruin of pulling out of the race that he began to fake his times and distances. He created a false logbook and never left the Atlantic. After a disqualifying stop in Argentina for repairs and supplies and then a sail down to the Falkland Islands for video footage to suggest he had come around Cape Horn, Crowhurst slowly sailed back north toward England in the hopes that with Knox-Johnston and Tetley claiming the prizes, his voyage would be highly honored but not too closely scrutinized. The stress of the voyage, his guilt, his mental state deteriorating, and the information over the radio that Tetley was out of the race—meaning that he would now win the fastest time and his treachery would surely be exposed in the most public fashion—proved to be too much. Crowhurst almost certainly took his own life by walking off his deck on a calm, sunny day in the middle of the North Atlantic, likely on 1 July 1969. His boat was found a week later by a passing merchant ship whose crew found nothing disturbed inside Crowhurst’s cabin. There was no evidence of any substantial wave action or bad weather. Dishes were piled in the sink and a can-opener on the counter hadn’t even rolled off. Although Crowhurst’s falsified logbook seems to have been taken with him into the sea, the logbook of his true progress was left on board, as were all of his audiotapes and film footage. The writings and film show him in an increasingly psychotic state. Donald Crowhurst left behind his wife, Clare, and four young children.

After the boat was discovered, Robin Knox-Johnston gave his prize money to Clare Crowhurst. Two journalists pieced together a careful, best-selling exposé, The Strange Last Voyage of Donald Crowhurst (1970), explaining what had happened. Nigel Tetley wrote his own book, Trimaran Solo (1970) as he tried to get funding for another go around the world alone, yet no one wanted to support him. He had been thoroughly upstaged by Knox-Johnston, Crowhurst, and Moitessier. In early February 1972, wearing women’s lingerie, his hands tied behind his back, Tetley was found dead in the woods of Dover, hanging from a tree. Suicide seems most likely, but the coroner could not be certain.

Knox-Johnston wrote his own book, too, of course. In A World of My Own (1969) he described how he kept calm and got on with it despite his slow wooden boat and multiple gear failures. Early in the trip, Knox-Johnston had to dive into the ocean to re-caulk and nail copper over seams that were leaking water into the hull from both sides near the keel. While Knox-Johnston was on deck resting, a large shark swam over and began circling his boat. Knox-Johnston wrote that he dispatched the animal with a single bullet to its head. When no other sharks appeared, he resumed his underwater repair.

Another day, after passing the Cape of Good Hope, he was doing some routine maintenance when battery acid splashed into one of his eyes. It didn’t come to this—he flushed the eye with water and bandaged it for some time—but he wrote that he was willing to go blind in one eye to achieve this first for England.

A World of My Own is like Chichester’s narrative in that it was primarily interested in technical descriptions and patriotic heroism. More than a fifth of Knox-Johnston’s onboard library, the list of which he published in an appendix, were books about oceanic natural history—field guides on fish, whales, birds, and two books by Rachel Carson—but his story as told was less interested in marine life beyond providing the flavor of his pelagic locations. Divorced at the time (he and his wife would later reunite) and the father of a young child, he did, however, pause with an awareness of giving something else to the larger world. This came out in a moment on Christmas Day in 1968, sailing in the Southern Ocean, during which he lamented that he would not be able to listen to the Queen’s speech. As he dined on steak, potatoes, peas, and currant duff, he compared his voyage to that of NASA’s Apollo 8 expedition after hearing about it on the radio, a moment quite similar to that felt by Sharon Sites Adams several months later, as she approached California after crossing the North Pacific. Knox-Johnston felt the space program contributed to scientific knowledge more broadly, something his voyage did not. But then he dismissed this idea of a broader good with the tone of the hero at the pub—with a shot of Davison-like candor:

True, once Chichester had shown that this trip was possible, I could not accept that anyone but a Briton should be the first to do it, and I wanted to be that Briton. But nevertheless to my mind there was still an element of selfishness in it. My mother, when asked her opinion of the voyage before I sailed, had replied that she considered it ‘totally irresponsible’ and on this Christmas Day I began to think she was right. I was sailing round the world simply because I bloody well wanted to—and, I realized, I was thoroughly enjoying myself.

For the record, I do not believe Francis Chichester, Robin Knox-Johnston, or any of these awe-inspiring single-handed mariners fabricated much if any of their major acts of almost ludicrous, stunningly impressive bravery and seamanship. I do believe, however, that they thought to themselves before, say, diving into the water after the shark’s blood had dissipated: this will make a good story.

Peter Nichols, who wrote the excellent account of this first Golden Globe race, titled A Voyage for Madmen (2001), had himself attempted a single-handed trans-Atlantic crossing and then later wrote about it in his narrative Sea Change. Nichols was the one who wrote about sea jellies reflecting human existence. Highly capable and experienced, he had nearly made it across, but a few days from Bermuda, swaths of the outer laminate of his wooden hull peeled away and the caulking spilled out. His boat began to leak beyond repair or any human ability to pump. He imagined Knox-Johnston diving to replace his caulking, but this would be ten times the job. As Nichols was choosing what to bring with him from his sinking boat, gathering the pages of the draft of his novel, he wrote: “I yearn to write something great and wonderful.” Throughout Sea Change his boat is an overt symbol of his relationship with his first true love, his ex-wife with whom he had purchased, repaired, and sailed the boat—but who he had recently abandoned. Both their relationship and their boat had been falling apart over time.

Do I think that Peter Nichols was reflecting on how metaphorically appropriate this was, how sadly perfect his sinking boat was for his future book, even as he was stepping up the ladder onto the merchant ship that had answered his mayday? I do.

I do not think, however, there is anything unethical or false in this. Aren’t we all doing this at some level all the time, always imagining an audience? It is part of that fair, old question: can you be a storyteller and be pure of endeavor at the same time? Is an adventurer, athlete, activist, politician, or even a social worker or teacher to be considered compromised, less “true,” if they know from the start that they are going to create something from it, craft some form of art or research project or any other form of creative or scholarly expression? Solo sailors present an exceptionally compelling case study in this fluidity of experience and art and story, because there is so long a tradition of the ancient mariner’s sea stories. There is no one to confirm the tale. For single-handers the stakes are often life and death, and the remains and the reality of a death are almost always unrecoverable and unknown. We will never know if Slocum’s Spray really did steer itself so well, if he did in fact escape pirates, or even how or when he died. “The sea is trackless, the sea is without explanations,” wrote the novelist Alessandro Baricco in 1993, lines written and spoken and painted and photographed and sung in slightly different ways by thousands of people over millennia before him and to be expressed for millennia to come. Put another way, it’s often quoted that the novelist Gabriel García Márquez once said: “Fiction was invented the day Jonah arrived home and told his wife that he was three days late because he had been swallowed by a whale.”

Donald Crowhurst, the person who entered the 1968 Golden Globe race with minimal offshore experience then faked his voyage and killed himself, seemed to have always been putting on an act since childhood. He was an amateur thespian in his town, performing in several plays. Before he left for the non-stop circumnavigation he was telling sailing stories to reporters that had never happened to him. Once at sea, as the months wore on and he floated alone in the South Atlantic, he steadily grew less and less stable due to the stress and solitude, however self-inflicted. He created in his logbooks and records and films a fictionalized depiction of his voyage, a new reality based on his previous readings of other sailors and what he was living, as he was living it. He went as far as writing a romantic poem to the Southern Ocean even though he was not even sailing in that part of the world. Chichester’s Gipsy Moth Circles the World was one of the few sailing narratives that Crowhurst brought aboard with him. Nicholas Tomalin and Ron Hall found passages in Crowhurst’s journals and recordings that are nearly identical to those of Chichester’s, perhaps cribbed unconsciously. The journalists considered the possibility that Crowhurst even play-acted his own madness, but concluded after consulting psychiatrists that it was too well performed to be unreal. The stress and isolation had sent him into a suicidal mania.

Donald Crowhurst posing on board his boat Teignmouth Electron months before leaving for the Golden Globe race (1969).

Consider the case of Bas Jan Ader. Only a few years after Moitessier’s masterpiece, in 1975 the Dutch artist, photographer, and conceptual performer, who had built his reputation using himself as a subject doing physical stunts or emotional displays, cast off from the coast of Massachusetts in a tiny pocket day-sailer that was only 12.5 feet long. Ader was thirty-three years old: tall, thin, with a big, endearing smile. He planned to sail alone that summer to Europe to complete a show scheduled to run in Amsterdam. He had been putting together a display titled “In Search of the Miraculous,” part of which he had already shown in Los Angeles. During this first installation some of his art students wore black and sang sea ballads. “A life on the ocean wave,” they sang, “a home on the rolling deep!” Photographs from his trip aboard his boat Ocean Wave were presumably to be placed in the center of his show after he arrived.

Ader had had some experience at sea before the trip. Prior to art school in Los Angeles, he had crossed the Atlantic and traveled through the Panama Canal as a crew member. His biographer Alexander Dumbadze saw Ader’s voyage this way: “He wanted to make a masterpiece, desperately. He figured, well, look, I can’t lose. Either I cross and I’m in the Guinness Book of Records, and/or I die—and you know what, it will be a phenomenal piece of work.”

About nine months after Bas Jan Ader cast off, in April 1976, a Spanish trawler near Ireland found Ocean Wave floating vertically, covered in gooseneck barnacles, the type that only grow on floating things at sea after months at very low speed. The Spanish Navy saw stress on the waterboards, suggesting, maybe, that Ader had been clipped in and was thrown out in big seas somewhere. No one knows how far he got. He did not have a radio with him. Any journal or film Ader made was never recovered. One of the fishermen snapped photographs of Ocean Wave when it was first found. Then someone stole the boat from the Spanish captain’s shed before Ader’s wife and his brother could see it and conduct any further forensics. In Ader’s locker at the art school, friends found a copy of The Strange Last Voyage of Donald Crowhurst.

Ader’s widow, Mary Sue Andersen, stated confidently, painfully, over and again, that Bas Jan never intended to die as art: he was not staging his death. Still, many clung to this idea during the years after. Or said that Ader was still alive somewhere, with secret plans to re-emerge in the ultimate work of performance art: reincarnation.

Bernard Moitessier left Plymouth, England, in August 1968, a few months after the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., after the “May 68” demonstration-strikes in France, and a few months before the release of the Beatles’ White Album. In 1968, Andy Warhol, the pop artist who so famously mixed celebrity, life, and art, oversaw his first solo show in mainland Europe.

Moitessier’s narrative of his non-stop solo trip around the world, The Long Way (1971), starts off in a similar fashion to so many of the other single-handed sea stories before his: at his departure from the dock. What Moitessier does uniquely from the first paragraph, however, is that he expresses himself in the present tense. This subtle style choice, a form more common in French literary writing, is a significant representation of his declared mindset as a sailor.

Aboard Joshua, Moitessier sails out of Plymouth in a scene in which he sounds, at least to twenty-first-century readers, like a selfish jerk. He speaks with great feeling for his fellow single-handers, but as he is sailing away, he writes that he says to his wife, who is crying: “Don’t give me the blues at a time like this.” He compares himself to a “tame seagull” who simply needs to go to sea from time to time.

As he sails south toward Madeira, riding in the Canary Current, Moitessier gives some brief back story on his entrance in the Golden Globe race. Implicitly, his identification with a seabird is his why-go. He simply needs to be alone on the open sea for parts of his life. Seabirds, as well as dolphins, are major characters in Moitessier’s narrative during his voyage. He anthropomorphizes marine life, to be sure: the ocean animals guide him spiritually and directly, but he does not give them human names like Blue Bill or Freddy Flying Fish. In his logbook intended for publication Crowhurst gave his animals storybook names such as “Desmond the Doddery Dorado,” a dolphinfish that he wrote was eventually eaten by a shark, and “Peter the Prior,” a seabird, perhaps a tern, which ate flying fish off his deck. (Crowhurst later wrote in one of his logbooks a short story titled “The Misfit,” about finding a weak land bird on the boat—with overt parallels to his own personal state.) Moitessier in contrast does not name his animals at all, yet as he sails on he describes himself growing more animal-like, seeing himself closer in behavior and intuition to the truly pelagic life of the ocean.

Like Slocum with Spray, Moitessier also sails in brotherhood with his beloved vessel, feeling his boat as a living, breathing being. Unlike any Western sailor-writer before him, however, Moitessier depicts himself sailing within, as part of, the very breath of the sea and sky and sun. Regarding the challenge of sailing the Southern Ocean, the most dangerous seas in the most distant inhospitable places for human life, he contrasts sailors with geographers: “A great cape, for us, can’t be expressed in longitude and latitude alone. A great cape has a soul, with very soft, very violent shadows and colours. A soul as smooth as a child’s, as hard as a criminal’s. And that is why we go.”

Moitessier makes exceptionally good time heading south in the Atlantic. He knows his boat. He has learned lessons from his last big trip, notably about what to bring and what to leave on the dock. His Joshua is prepared to be knocked flat and flipped over. He can steer it from a little steel turret cockpit. His deck is clean of gear and lashings, of nearly any electronics or any bells and whistles, even almost entirely absent of any wood that could rot or need varnish. His self-steering system is simple, hand-built, and long-practiced. Before he leaves, he offloads hundreds of pounds of unnecessary weight. As the voyage progresses he continues to fling things over the side that he deems no longer useful: gear, food, fuel, repair cement (after he clears the region of possible icebergs), anything that he knows he no longer needs in order to help his boat sail more freely, lighter, in better trim. As he flings things merrily overboard, he makes no comment about non-biodegradable garbage.

Continuing south, Moitessier observes the flying fish that signal tropical waters, eats them with gusto, and watches them preyed upon by dolphinfish, which he also captures and eats, drying their flesh in the rigging. He writes of one moment where a barracuda, leaping out of the water, captures a flying fish in mid-air, even adjusting itself above the surface to snatch its prey. Moitessier does not observe marine life in conversation with other sailors—there is no competitive ecology here. His tone is closer to that of Pidgeon at the end of his voyage, but with far more detail and book learning. Moitessier writes not of how he is consulting field guides, but how he is reading more thematic books such as Jean Dorst’s Avant que nature meure (Before Nature Dies, 1965), a global overview of humanity’s negative impact on natural systems and species, which Moitessier describes: “All our earth’s beauty . . . all the havoc we wreak on it.” Moitessier records what he sees on the ocean, lovingly, more often raising questions, occasionally using Darwinian phrases such as when regarding the flying fish and their “struggle for life,” but he also writes in the same breath like Slocum, with a near-religious belief in a master spiritual system, wondering about predation and the lives of defenseless prey, the tons of crustaceans killed in one gulp by a whale: this “must have some purpose.”

While still writing of his passage outbound in the Atlantic, Moitessier in The Long Way further distinguishes himself from previous narratives in his discussions of weather and oceanography. Moitessier uses pilot charts and weather reports, like the others, but he speaks in far more detail about currents, wind patterns, ocean depths, wave directions, and low- and high-pressure systems, all carefully and well explained to his lay audience. His voice is one of long experience, but also humility. In an appendix, Moitessier makes clear that the ocean’s weather and sea states are too variable and complex for full human knowledge. “The sea will always remain the great unknown,” he says. “It is sometimes enormous without being too vicious; not as high a week or a month later, it can become very dangerous because of either cross-swells, or an unexpected or completely new factor. The person who can write a really good book on the sea is probably not yet born, or else is already senile, because one would have to sail a hundred years to know it well enough.”

Arriving off the Cape of Good Hope, Moitessier wants to report himself safe and to send home photographs of his logbook pages and rolls of film. He uses a slingshot—a skill he learned as a boy in Vietnam—to zip messages in cannisters onto the decks of passing ships. As he tells it, he gets too greedy here and the merchant ship steers too close. The collision badly bends Joshua’s steel bowsprit. In the following days Moitessier manages to pull the spar back into place by cleverly using a tackle rigged through an outboard block on the staysail boom then led back aft to a winch.

Once clear of Good Hope and his Joshua repaired, Moitessier enters the Indian Ocean, which he believes to be the most treacherous in the world. He enters a new phase of connection to the sea.

If Chichester’s classic feels at times to modern readers a bit too technical and stiffly performed, Moitessier’s masterpiece, in its own way, feels over-acted in its evocation of the author’s spiritual relationship with an oceanic natural world. One almost expects Moitessier to move into a discussion of healing crystals and essential oils with language, at least in translation, that would make Ann Davison gag. Moitessier builds this all up slowly in The Long Way, increasing, opening, as he travels farther and farther from shore into more desolate seas, physically and metaphorically, with several references to Hemingway’s fictional character Santiago, the old man who ventures too far into the ocean and to the limits of his endurance when searching for a big fish that means far more.

“I wonder if my apparent lack of fatigue,” Moitessier writes as he scuds eastwards in the Indian Ocean, “could be a kind of hypnotic trance born of contact with this great sea, giving off so many pure forces, rustling with the ghosts of all the beautiful sailing ships that died around here and now escort us. I am full of life, like the sea I contemplate so intensely. I feel it watching me as well, and that we are nonetheless friends.”

Heading toward Australia, staying north of any threat of ice and the highest of winds, Moitessier finds weather more temperate than he expected, if at the expense of a loss of speed. He begins to study yoga at sea, sometimes practicing naked on deck and absorbing the sun. Although his hair and beard grow long and matted, he’s amazed that he never needs to wash with soap; his skin remains perfectly clear. Between sail changes and light maintenance, he drinks coffee, smokes cigarettes, drinks an occasional glass of wine. He reads books. He watches and watches and watches the ocean and the birds. His self-steering gear is always working well. He shoots video footage, writes and sketches in his journal. He fishes. He takes sun sights for navigation.

Bernard Moitessier’s photograph of himself doing yoga aboard Joshua during the 1968–9 Golden Globe race.

Although Moitessier presents himself in The Long Way as more of a hippie cruiser than a racer, he is traveling far faster than Knox-Johnston and faster even than did Chichester. At his sailing school in the Mediterranean, eager to convey the need to watch the swells and the wind direction, he shunned compasses in his navigation teachings. In The Long Way he speaks highly of the traditional navigation of his mentors in Southeast Asia. He is in practice no less exacting and careful than Knox-Johnston or Chichester, nor does he shun most modern technologies. Moitessier has been a devoted reader of previous narratives, such as Slocum, Pidgeon, John Voss, Conor O’Brien, and Vito Dumas, all of whom he credits. Before the trip he corresponded with as many Cape Horn captains as he could, including commercial mariners who had sailed in the Southern Ocean. In his lengthy appendix he includes information that might distract from his present-tense spiritual story, meticulously detailing his choices of rigging, paint, anti-rust systems, different metals, sail-stitching methods, food, types of socks and boots, all of his small and large lessons, which he openly shares without a didactic or definitive tone. Moitessier navigated with celestial navigation and dead reckoning, using a wristwatch and a chronometer that he checked regularly with his one-way radio, everything dutifully written out. When he could hear weather reports over the radio, he recorded them on a tape cassette so he could play them back and work out the long-term trends. He incorporated all this into a more sensory experience of his voyage and his day-to-day practice: “Now I listen for the threat of a gale in the cirrus and the sounds of the sea.”

In the relative calms of the Indian Ocean, Moitessier writes of sharks, how he does not fear them exactly, though he is always quick to be ready to get out of the water. Sharks, he explains, are usually just curious, not aggressive—that is, except for the big ones. Moitessier does not pull out a gun to shoot at them.

Moitessier watches albatrosses, cape pigeons, and what he calls “cape robins,” a type of petrel he is unable to identify. He writes of the variability in plumage of seabirds and their flight patterns, and how birds in the deep Southern Ocean are less social than those of the temperate or tropical regions, like the tropicbirds and frigatebirds. These Southern Ocean birds, he writes, are constantly seeking, searching, earnest, which he sees as like himself. Moitessier grows especially close to a flock of shearwaters that learn to recognize his call. Each day he feeds the shearwaters butter, paté, and dried dolphinfish. The birds grow so familiar that at the end of his time in light airs before Cape Leeuwin, he feeds a couple of shearwaters out of his hand.

Now into the full wind and waves of the Southern Ocean, continuing under the continent of Australia, Moitessier pauses off the coast of Tasmania to pass letters and a package of film to a few fishermen that he happens to see near port. From here he continues below Aotearoa New Zealand and begins the haul across the broad Southern Ocean of the Pacific on the way to Cape Horn. He writes that he is feeling secrets between his boat and himself, connections that cannot be captured on film: sounds, realizations, and internal expansions in his conversations with the ocean that is leading him to existential, personal truths. He is reading John Steinbeck, Romain Gary, and Antoine de Saint-Exupéry. He writes without any direct reference to Crowhurst—the reality of which he knew by the time he sat down to write The Long Way—but Moitessier recognizes that he too sails on the thin edge of sanity.

On his approach to Cape Horn, now having spent over five months alone at sea with only two brief shouted conversations across the rail to other mariners on boats off Good Hope and Tasmania, he witnesses and details a display of the Aurora Australis, the most beautiful thing he says he has ever seen. He is reaching the outer reaches of the sublime. Rounding Cape Horn, Joshua sails fast, surfing down large seas, at times at the edge of his control. A full moon lights the evening from behind the clouds, painting the entire sea luminous, its reflection mixing with bioluminescence in the water and the sparkling night-time spray on his sails as the bowsprit plunges ahead. Moitessier forgets himself as he becomes part of the scene, standing on the windward side, clipped in and holding on to his mainmast and the main halyard, like an Odysseus before starry sirens. His story is at a physical climax. The northwest wind whooshes across from Patagonia. He searches to sense the seaweed and the ice. He needs to remind himself not to go stand on the bowsprit, to cinch his hood back on his head so his ears don’t freeze. But he wants to feel everything. He wishes he could be barefoot. At one point, standing on deck as Joshua hurls down seas that are laced with moonlit froth, his body becomes so relaxed, he feels so out of his physical self, that he does not even notice until afterward that he has urinated down his leg into his boot.

Moitessier loses himself in the dangerous beauty of this passage, describing droplets of sea spray as jewelry on the sails. Joshua crashes through mists and surfs down the icy seas around phosphorescent orbs of “plankton colonies” that appear to him like the eyes of giant squids. He admits that he has gone too far. He should reduce sail, but everything is humming. He wants to get beyond Cape Horn as fast as possible. He writes (his punctuation):

A gust. This time Joshua luffs with more heel. The bowsprit buries itself and solid water roars across the deck. I grip the stay hard. The little wind vane is still there. It must have been dunked in the sea when we heeled, but did not break. I blow it a kiss.

A sea approaches, fairly high, all light at the summit, black below . . . and vrooouuum . . . the keel hardly wavers in the 20 or 25 yards. A great plume shoots up on either side of the bow, climbs high, filled with swirls which the wind throws down into the staysail, and some into the storm jib.

I listen. One surfing run taken the wrong way in the clear night . . . and my beautiful bird of the capes would go on her way with the ghosts in the foam, guided by a seagull or a porpoise. I am not sure which I would prefer, a gull or a porpoise.

Joshua drives toward the Horn under the light of the stars and the somewhat distant tenderness of the moon. Pearls run off the staysail; you want to hold them in your hand, they are real precious stones, that live only in the eyes.

At the height of this glory, Bernard Moitessier and his Joshua weather Cape Horn.

In the days to follow, hungover from his last great cape, he sails, spent and fatigued, up to the Falkland Islands in the hopes of leaving film and letters and assuring his family that he is okay. He slows down past the lighthouse there and hopes to encounter a boat or ship of some kind. But it is a Sunday. He is too tired to risk steering in towards the harbor, so he continues on up north into the South Atlantic.

He is seen, however. The lighthouse-keeper reports him back to London. At this point, Moitessier is only a couple of weeks behind Robin Knox-Johnston and gaining fast. Based on these few positions, reporters in England predict a neck-and-neck finish for the first one home, the claim for the winner’s country to be the first person in history to accomplish this Everest-of-the-ocean challenge. All believe that Moitessier is sure to win the money for the fastest time even if he doesn’t finish first—unless Tetley and Crowhurst can continue their speeds. Moitessier knows none of this, having only heard from the Tasmanian fishermen something uncertain about an Englishman who had passed by weeks earlier.

As Moitessier sails up into the South Atlantic, toward calmer, safer waters, he finds himself conflicted, even afraid of returning to the materialism of Europe. He wants to see his wife, his stepchildren, his mother who is growing old, but the return to France feels to him like giving up. In The Long Way, the story of the voyage, he has been teasing out this longer mission to keep going, to ignore the race and the return to Plymouth, to keep sailing all the way back to the South Pacific, another full two-thirds around the globe, but these hints are only clear if you know already what is going to happen. In a story-telling strategy used by Horie and Chichester to infuse authenticity, in The Long Way Moitessier includes a photograph of a page from his onboard journal, in which he scribbles the existential climax of his masterpiece: “I have set course for the Pacific again.”

Moitessier admits to benefitting from the technologies of modern society, but he cannot accept the modern world, “the Monster,” which is “destroying our earth, and trampling the soul of men.” He has been debating, wavering, and then he finally leaves it up to the winds, the seas, to tell him which direction to go. To answer, the winds blow favorably toward South Africa. While Moitessier sits cross-legged and naked in the cockpit, a white fairy tern, the same species of bird that once welcomed Slocum to Cocos Keeling from his passage across the Indian Ocean, lands on Bernard’s knee. He writes that with its large black eyes the seabird tells him a fable about how the people on the ship of life have grown fat, have accepted mediocrity and ugliness. The ship of the world is headed for disaster. The people don’t heed the word of the barefooted sailors. The captain is just waiting for a miracle, “but he has forgotten that a miracle is only born if men create it themselves, out of their own being.”

Moitessier includes his own cartoon of a fairy tern with his boat, the sea, the sun, and an island. This is an illustration motif that he apparently used regularly in his letters and to sign his books. The drawing is etched onto his gravestone.

Bernard Moitessier’s drawing of a fairy tern and his boat in his narrative The Long Way (1971).

He makes his decision that spring of 1969. In one of the most profound single acts of performance art in recorded history, a couple of months before Neil Armstrong’s one step on the moon, from the deck of Joshua Bernard Moitessier flings with a slingshot a cannister that lands on the deck of a ship off Cape Town, South Africa, perfectly named British Argosy. Addressed to the Sunday Times newspaper, the message inside reads: “The Horn was rounded February 5, and today is March 18. I am continuing nonstop towards the Pacific Islands because I am happy at sea, and perhaps also to save my soul.”

Off Cape Town, Moitessier also dispatched a jug filled with still and movie film, cassette tapes, and letters—enough he believed to make the book if something happened to him. He continued sailing alone, across the Indian Ocean again, under Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand again, another halfway around the globe and on to French Polynesia, where he tied up at last in Tahiti and set foot on land for the first time in ten months. Meanwhile, the newspapers in Europe had exploded with the news. His wife was mobbed for comment. She told the press that she was pleased that Bernard had his full freedom.

Once in Tahiti, Moitessier began work on writing The Long Way. It took him two years to finish. He donated the royalties to the Pope, to distribute as he wished to better the world. Uncharacteristic of most of these solo captain stories, The Long Way does not end when he ties up to the dock in Tahiti. Moitessier’s story continues further to explain how his fellow sailors were distressed by the cutting down of trees to make a waterfront highway in Papeete. He wrote of how good it would be if the cities and towns of the world began to plant more fruit trees—for the food, the shade, and the symbolism. From the dock in Tahiti, he wrote of the ailing human race, of “robot-man,” the “Corporate State,” the machines that must keep making new roads and buildings in order to reproduce, that people are swarming all over the earth on a “suicide tack.”

Fruit trees became a major cause for Moitessier for the rest of his life. He wrote hundreds of letters to world leaders, town leaders, and he teamed up with environmentalists when he could. The Vatican never claimed the royalties, so he offered to send funds privately to any community that wanted to plant fruit trees. Only a couple of small towns in France took him up on the offer.

Moitessier mostly remained in French Polynesia at first. He remarried, they had a son, and the family spent three years living and planting on a remote atoll, trying to bring in a new type of sustainable agriculture and to raise their child in a simple way close to nature. Occasionally, French filmmakers came to him wanting to write about his exploits or to make documentaries about him, but Moitessier was particular about his messaging. He demanded that in interviews the topics of fruit trees and nuclear disarmament be the main points of discussion.

When the island experiment fizzled out, he and his young family sailed to San Francisco. But the United States disappointed him. He was not able to make a living there. In 1982, at fifty-seven years old, Moitessier left his second wife and son in San Francisco for a time to head south on Joshua again. Here his boat wrecked in a hurricane while at anchor off the coast of Mexico. He built a new boat, a smaller one, and returned to Polynesia. In 1986, Moitessier returned to France where he worked for several years on a fourth and final book, a memoir, reaching back to his childhood in Vietnam.

Bernard Moitessier died in 1994 in France. He lived to see Joshua refurbished and donated to the Maritime Museum of La Rochelle, where it still lives and is sailed by devotees.