21. Bill Pinkney and Neal Petersen: For the Children

Less than three years after Teddy Seymour tied up Love Song at the dock in St Croix after altering his entire cruise track to avoid South African racists, another African American man named Bill Pinkney sailed into Cape Town. It was on the morning of 13 December 1990. This was Pinkney’s first sighting of “Mother Africa” after a thirty-four-day passage from Brazil. It was shaping up to be a bright, clear day in Table Bay. As the day opened, the wind blew favorably, allowing him to set a huge, light air spinnaker that had bold red, green, and black stripes to symbolize the African American struggle for freedom from discrimination in the United States. He had commissioned this sail particularly for this moment.

“I wanted all to see who I was and where I came from,” Pinkney wrote in his story of his voyage, titled As Long As It Takes: Meeting the Challenge (2006).

Once near Robben Island, the prison island from which Nelson Mandela had been released only months before, Pinkney steered his boat Commitment beside another sailing yacht that had emerged out from behind the harbor’s breakwater, the only other boat out that morning. This was skippered by Neal Petersen, a lighter-skinned South African who also identified as Black. Petersen was sailing with his parents on board. This meeting on the water in Table Bay would hold profound significance, connecting national histories, generations, geographies, and the sail-racing communities.

Bill Pinkney, fifty-five years old, was balding and had a salt and pepper beard. This was his first solo ocean-crossing, and he was attempting to become the first African American to sail around the world by way of the Southern Ocean. Several years older than Teddy Seymour, Pinkney had grown up in poverty on the south side of Chicago where he endured several events as he grew up that painfully proved to him the racism inherent in American society. Raised by a single mother who cleaned people’s houses, Pinkney did not find a passion for school until the seventh grade when he discovered a love of reading, enjoying books given to him by an energetic, committed teacher named Gladis Berry. Here he came upon Call It Courage, a story with which he immediately identified and would carry with him his whole life. He fantasized about sailing off and returning as a new man. “It was a dream of a great adventure like the young boy’s—sailing off to become my own person and to return home a hero,” Pinkney wrote. “That was the beginning of what was to become my dream to sail around the world.”

To make his mother proud and secure a better job, he traveled across town to a pre-engineering high school. One day he arrived to find that someone had spray-painted in enormous letters “N****R TECH” on an outside wall.

After graduating from high school in 1954, Pinkney chose not to go to college. Like Seymour, he saw the US military as a path of opportunity, so he joined the Naval Reserve, still thinking about Call It Courage. He tested well and became an officer in the medical corps—despite the white recruiter urging him to be a ship’s steward, to be with his “own guys.” During his time serving his country, Pinkney experienced first-hand the harsh realities of the Jim Crow south, where he was forced to ride buses separated by race, watched new friends step off the sidewalk when white people came in the opposite direction, and found he would not be served in certain stores.

After his service in the Navy, Pinkney, feeling suffocated in the south, divorced his first wife, whom he had met in Florida. He left behind a young daughter and ran away to Puerto Rico. Here he found work with an elevator installation company and as a hired limbo dancer in clubs where he faked a Caribbean accent for tourists. In Puerto Rico he learned how to sail, volunteering on an inter-island ferry. It was now the early 1960s. He moved to New York, converted to Judaism, continued to read sailing stories, got a bit of ocean-sailing experience as a crew member, and remarried. He worked as an X-ray technician and then trained as a make-up artist for low-budget films before moving to mainstream celebrities, specializing in Black skin and hair, which all led him to move up the ladder until he was an executive at Revlon. This profession brought him back to Chicago, working for a highly successful Black-owned beauty products company. Now Pinkney and his wife had a bit of money, so he began to sail regularly on Lake Michigan. He bought his first boat (a Pearson Triton, coincidentally, the same design as my boat). Pinkney became the only Black member and then the commodore of his yacht club in Chicago. At the age of forty-eight, he lost his latest job in public relations for the city of Chicago because of a change in administration. So now with his fiftieth birthday looming, he decided he wanted to make a solo world voyage happen while he was still physically able. He had reconciled with his daughter, who had two kids of her own. He thought often about how his life had gone, the choices he made to leave his young family. He wanted now, he said, to leave a legacy, a “benchmark” of which they would be proud. He decided that along the way he would write letters to his grandkids.

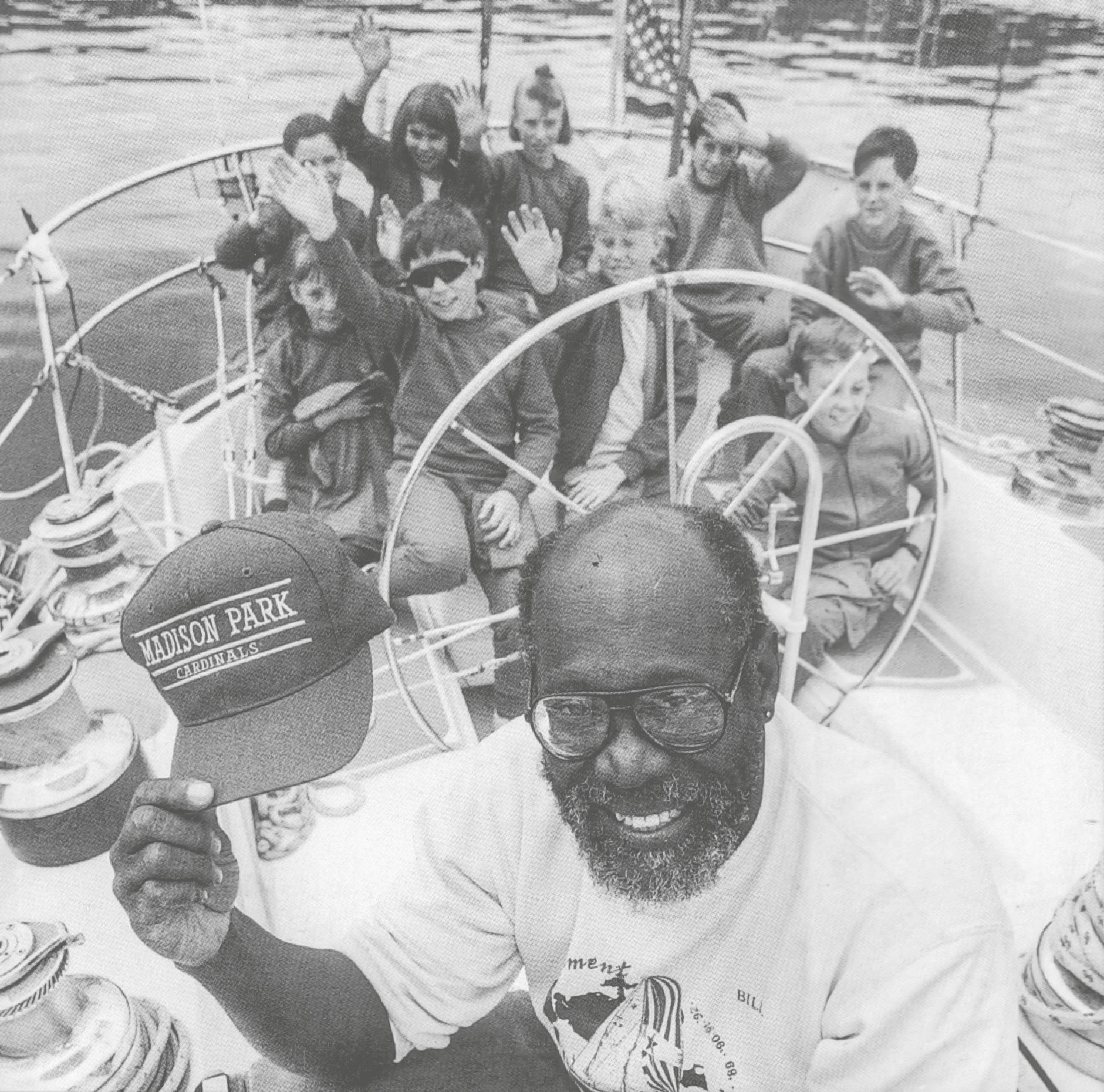

Pinkney began the grind of finding a boat and raising the money. Single-handed sailing narratives, beginning in the 1980s, especially those with an interest in racing, now nearly all included the trials not of building a boat but of raising money and finding sponsors to fund and fit it out. Pinkney spoke about education and inspiring schoolchildren. When word got around that he was going to write letters home, not only to his grandkids but to his former elementary school, the entire Chicago public-school system wanted this correspondence. So he planned to film himself on board with a hand-held camera and then mail the videotapes home when he got to port. Kids in schools, he said, could follow the vessel’s progress and occasionally even connect to him over the long-distance ship-to-shore radio. Pinkney found a major sponsor in Boston, who arranged a similar program for public-school kids there. It became essential to Pinkney’s why-go for him to prove to children the value of following a dream and to model for them his commitment to keep going, to endure and make it around the world. “Now I had thirty thousand grandkids,” he told me.

Pinkney explained that as he planned his voyage he did not know about Teddy Seymour, or about Neal Petersen, a teenager in South Africa, who was growing up desperate to sail around the world. Pinkney did know, however, reading his Cruising World magazine, about Tania Aebi sailing alone into the Pacific that year and about Dodge Morgan, who became the first American to circumnavigate the world non-stop. He would watch Morgan’s documentary Around Alone (1987), made from footage he took while on board, and he read Morgan’s narrative, The Voyage of American Promise (1989), over and over again as his primary logistical reference. Pinkey had read his Slocum, too, and he had read Dove. Meanwhile Pinkney continued to plan, raise funds, and organize. He networked with various businesses and contacts with connections to sponsors. Through a contact of a contact, he was flown to London, where his host arranged a visit to a house with a large bronze dolphin door knocker, the home of none other than Robin Knox-Johnston. Pinkney was in “hog heaven,” sitting around petting the family dog, eating tea and toast, and gawking at the Golden Globe trophy and other sailing ephemera. Knox-Johnston told Pinkney that a circumnavigation using the canals would be quickly forgotten, because whatever record he set as the first Black person to do so would be quickly surpassed. “They’ll never know your name,” Knox-Johnston told him. “If you’re going to do it, do it like a man.” He told Pinkney that he must go around the big capes by way of the Southern Ocean. Pinkney walked out of Knox-Johnston’s house convinced that he should indeed circumnavigate via Cape Horn.

Although Pinkney was not exactly racing, he had no plans to sail the Southern Ocean in the likes of Slocum’s Spray or even a stout pocket cruiser like Seymour’s Love Song. Even if he could get a suitable boat on loan, which he eventually did, he needed to raise several thousand dollars for the voyage. Through a major sponsor, Pinkney managed to borrow a large, stout forty-seven-foot ketch, a proven vessel that another sailor named Mark Schrader had already sailed to complete a circumnavigation race. Pinkney renamed the boat Commitment.

During his preparations for the voyage he read a book by D. H. Clarke, who kept track of small-boat milestones for the Guinness Book of World Records, titled The Blue Water Dream: The Escape to Sea Syndrome (1981). Pinkney sent Clarke a letter requesting advice. He received a kind but sobering reply. Clarke said that of all the people who wrote to him about solo circumnavigations, only five percent even got a boat, and of them only five percent ever left the dock, and of them only five percent ever sailed beyond their closest ocean. At the top of his computer, Bill Pinkney posted a sign to remind him of this attrition rate.

After that morning in Table Bay and his visit to Cape Town, during which he toured around and reflected on the apartheid of South Africa—finding the people there far kinder than the system—Pinkney continued on to complete his world voyage, including the rounding of Cape Horn. He stopped in Tasmania, Brazil, and Bermuda. Beyond his moments with pilot whales, discussions of threatening waves, and a seemingly encouraging albatross he imagined to be a reincarnation of someone at home helping him persevere, for Bill Pinkney the organisms at sea, or even the ocean itself, although “all-powerful” and “relentless,” were barely present in his story of his life and this voyage, As Long As It Takes. Pinkney, who sailed with the new GPS technology, more often described the logistics of planning and running the voyage. He wrote of gear failure, inspirational communities in ports, cultural observations, and his bouts with fear, fatigue, and loneliness. On Thursdays while at sea, he rewarded himself with watching videos of television shows recorded for him at home. Once in a lightning storm off the coast of Uruguay, his boat stable, he stopped fretting about what he could not control, went below, had a shot of whiskey, and put on headphones to listen to the operatic soprano Kathleen Battle. He ignored the threats outside as his wind-vane self-steering took care of the sailing. Another time he was so ill at sea, perhaps with the flu, that his voyage track for a few days looked to those ashore as if he must have fallen overboard. With something like this in mind before he left Boston, Pinkney had filmed a video of himself addressing the children in case he were to die out at sea. He remembered the community trauma when the teacher Christa McAuliffe and six other astronauts died in the explosion of the NASA space shuttle Challenger in January 1986. As soon as he was well enough, he made his contacts to shore to make sure they knew he was okay: no need to play that video.

Despite his emphasis on his connections to schools and the logistics of the voyage, Pinkney did write about “one of the most spiritual experiences of my life.” One night he sailed Commitment on a flat sea with “billions of chips of light” in the sky reflecting perfectly in the calm dark water. The vision led him to feel, just for one second, that he was part of the universe and the span of deep time: he had a humble destiny, and he felt at peace with his small role, no lesser or greater than any other person’s for their blip of time on Earth.

As a storyteller, Pinkney perfectly placed this lovely moment at sea directly before his arrival in Cape Town, contrasting it with his fear of the racism he would see and experience. This evening of starry peace also happened the day after a near-death experience with a large fishing vessel from Taiwan. The ship crossed his bow while he was napping during the day. Pinkney woke up for his visual check on deck and saw the stern of the vessel, reading “Taipei” as the home port, only “spitting distance” away. He had forgotten to set his radar alarm. As his heart was pounding and the ship’s wake slapped against Commitment, he thought, “Had the ship seen me and changed course? Or had this near miss been an incredible piece of good luck?” In his narrative he does not return to this moment again, but it was an event that stuck with him, a story he often selected when telling of his voyage up into his eighties. It’s a story that is exceptionally poignant for me. Pinkney told me he does not remember the smell or the sound of the engines. “It was one of those things that the visual stopped everything. And boats that size when they’re really moving don’t make a lot of wake or engine noise.”

Holding up his hat from Madison Park School in Boston, Bill Pinkney hosts local schoolchildren on his boat Commitment during his stop in Tasmania (1991).

“Six feet off the water, your horizon in any direction is two and a half miles,” he said when remembering this near miss. “A big ship like that can be down below the horizon, over you, run you down, and be back over the horizon again in something like twenty minutes—or less depending on how fast he’s going. No one would know.” Pinkney told the story of a photograph he once saw of a big freighter with its anchor sticking out of the hawsepipe on the bow. “And on the anchor is the upper portion of the mast of a sailboat.” He reasoned in retrospect that the vessel had been illegally fishing in Brazil’s exclusive economic zone, so the crew was not only unwilling to reply on the radio, but would never have reported any collision.

On Bill Pinkney’s return home to Boston, the docks crammed with kids, he primarily saw his solo circumnavigation as an act of personal and patriotic pride, for his family legacy, and, again, to inspire children. Consciously representing Black America, he wrote in As Long As It Takes that the ocean, if you could get out there, offers a chance to prove oneself on “a level playing field,” regardless of skin color. Officials in Chicago named a street after him. His feat was read into the Congressional Record. A film documentary came out soon after and his memoir and narrative of the voyage followed several years later. “In hindsight,” he wrote, “I see that sailing has also served as a visible metaphor for the voyage of life itself.”

Pinkney went on to skipper a large sailboat from the Caribbean to Brazil and across the Atlantic to historical slavery ports in Africa, with high-school teachers aboard in order to teach children back home about the Middle Passage. Then in 2000 he became the first captain of the schooner Amistad, a replica of the coastal ship aboard which African captives rebelled off Cuba in 1839 and eventually, by way of the US Supreme Court, claimed their freedom to go back to Africa. He commanded Amistad across the Atlantic and to ports in Africa. Bill Pinkney died from a fall on a staircase at the age of eighty-seven, but he had been until the end back living in Puerto Rico and running sailing charters out of Old San Juan with his third wife. His last work was a children’s book, Sailing Commitment Around the World (2022).

Bill Pinkney’s boat Commitment had originally been built to participate in a solo sailing race called the “BOC Challenge,” one of the many single-hander events that began emerging from the 1970s into the 1990s, after the Golden Globe race of 1968 and the ever-growing popularity of the OSTAR, that trans-Atlantic race that began in 1960 with five people. In 1978 another trans-Atlantic race began; this one going more southerly and downwind, named the Route du Rhum, which left from Saint-Malo in Brittany. British Oxygen Corporation founded their BOC Challenge round-the-world race in 1982, which went around the southern capes with four stops along the way. This was held every four years, scheduled not to conflict with the OSTAR. Then in 1989 another solo round-the-world race began, the Vendée Globe, starting in Les Sables d’Olonne in the Vendée region of France. This was in the spirit of the first Golden Globe, totally non-stop. The OSTAR, and a similar race in the North Pacific, a “Trans-Pac,” had now become a sort of training run, an appetizer, for the single-handed round-the-world races.

Although several amateur cruisers entered the OSTAR or the larger races just to try to finish, the why-go of these solo races became more aligned with technological development, financial backing, and nationalistic pride. In contrast to cruisers, the new racing single-handed sailors, aiming foremost for speed, now required large high-tech boats, significant capital, and a shore-based team to support them before and during the voyages. The smaller races, including the OSTAR and its spinoffs, still allowed for a few shoestring sailors who wanted to challenge themselves just to cross the finish line. But even this became harder and harder for sailors on a small budget as the years progressed.

On the morning in Table Bay in 1990 when Bill Pinkney sailed in aboard Commitment, Neal Petersen was the person at the wheel of the much smaller racing yacht, a boat painted bright red and named Stella-r. Petersen had directed the design and the building of this himself. Born in 1967, he was still in his early twenties and more than a generation younger than Pinkney and Seymour. Petersen wanted to be a single-handed racer, to compete, and, like Bill Pinkney he felt that his why-go must be at least in part to inspire children and instill the potential for the realization of dreams: transcending any person’s disadvantaged upbringing to pursue a given passion and goal.

Petersen had scraped together the money for his boat by working as a scuba diver for a diamond-mining company. Tall, even gangly, he had been born with a hip defect. As a child he suffered through several surgeries on the “blacks-only” side of the hospital and then spent nearly a year in a cast, requiring him to walk with a cane into his teenage years. Yet as early as the age of twelve he began dreaming about sailing and the ocean.

“The solo sailors Joshua Slocum, Bernard Moitessier, and Francis Chichester and the diver Jacques Cousteau were my idols,” Petersen wrote. “The libraries were segregated. I was supposed to use ‘our’ one-room branch, but I’d make the painful hobble to the white library. The librarian there recognized my hunger, my ambition, and, being a brave woman, she turned a blind eye to my color and went out of her way to gather sailing books for me.”

Petersen never got out of his head the dream of sailing around the world alone. His father dived for abalone, so he learned to dive, too. Then he talked his way onto sailboats, all owned and sailed by white people in Cape Town. As the years went on, he scrimped and saved and studied to design and help build his boat. While training for a professional dive license in the US, he traveled to Chicago to meet Bill Pinkney to learn about how he was making his voyage happen.

Now in Table Bay in 1990, after waving goodbye to Pinkney from the decks of their boats and then connecting later ashore, Petersen soaked up the inspiration. As Pinkney was sailing southeasterly into the Indian Ocean, Petersen began his sea trials on Stella-r., named for an unrequited love, then sailed north, his first solo passage, having never navigated in the open ocean before or used a sextant in real conditions. He made it successfully up to the Cape Verdes and then to the Azores, with the plan to compete in the OSTAR in 1992. About ten days away from his arrival in England, Petersen was sailing at top speed, surfing at over fifteen knots, when he hit something: what he believed to be a submerged container that had fallen off a ship. This snapped his rudder, broke supporting timbers inside his boat, and loosened the keel’s connection to the hull. He rigged a clever makeshift steering system with a bucket towed astern and sailed slowly ahead. He limped toward shore and then was towed by a fishing boat into Galway, Ireland, nearly dying of thirst because in bad weather half his water supply had broken its lashings and leaked out.

Petersen’s sailing career from here is a continual story of extreme single-minded determination, a decades-long response to misfortune and trial from which each time he responded by dusting off and then getting back out to sea. Petersen found a home base in Ireland, competed and placed well in the OSTAR (having to turn back at the start after running into a floating plank), and then on the return to Ireland he met a woman named Gwen Wilkinson who would be his romantic partner for several years. Wilkinson cared deeply about the natural environment, inspiring Petersen and helping him tap into new sponsorship. He renamed his boat Protect Our Sealife. Petersen’s why-go, however, was really more focused on personal challenge than marine conservation. Like Pinkney he was passionate about inspiring kids to persevere and dream, writing in his narrative Journey of a Hope Merchant (2007): “From Bill I would learn to tie racing sponsorship to the education of children and inspirational speaking.” Petersen has a gift for holding an audience, and even today he still loves to visit schools.

Petersen next competed in a westbound trans-Atlantic race, which, despite some damage along the way, he finished. He entered the BOC Challenge around the world, but after a triumphant return to Cape Town for the first stop, he capsized soon after leaving on the next leg, barely off the Cape of Good Hope. His mast snapped, and he had to return home. Dauntless, he fixed up the boat and completed the final leg of the race from Uruguay back to Charleston, South Carolina. Before this final leg, though, his sailing mentor, his “seagoing father” Harry Mitchell, aged seventy, died without a trace in this same race. He presumably capsized and sank in exceptionally heavy winds and seas off the coast of South America after rounding Cape Horn. Mitchell had activated his distress beacon, but at that point he was beyond the reach of search planes. A vessel from the Chilean Navy had to turn back because the weather was so bad. This was the same weather system that capsized the boat of single-hander Minoru Saito, who was also presumed dead until he re-emerged weeks later, having lost all his electronics, radio, and steering.

Still undeterred, Neal Petersen kept racing. He sailed in the 1996 OSTAR. Despite Protect Our Sealife being holed after a glancing blow from a Russian merchant ship, leaking once again mid-ocean, Petersen pumped his way along, as before, and finished in third place in his class.

Neal Petersen sailing his boat No Barriers out of Cape Town, bound for Auckland on the second leg of the 1998–9 Around Alone circumnavigation race (1999). Note the servo-pendulum wind-vane self-steering gear, with the little rudder tilted up and not in use.

He continued to court sponsors and repair his boat, now named No Barriers. He entered in the next four-stop circumnavigation race in 1998. His partner by this point, Gwen Wilkinson, who had been traveling from port to port and living with him whenever possible, had endured enough and returned to Ireland for a different kind of life. Petersen chose his sailing goal over the relationship.

Petersen at last successfully sailed solo around the world, making it around Cape Horn and below the other scary capes. Along the way, like Pinkney before him, he sent home videos—technology now enabling this over email—and from his cabin at sea he wrote a newspaper column and connected live to children in their schools through his No Barriers Education Foundation. He finished safely this time, in the middle of a pack of nine people (out of fifteen entrants) who managed to finish. He was the only South African and aboard the only home-made boat in the race, which was the smallest of the fleet.

Neal Petersen has done little sail racing since then, but he has remained heavily involved in the education of kids around the world. He has been traveling with his new partner, sailing on a boat in the Caribbean, and giving motivational speeches whenever he can. He and Bill Pinkney remained in touch and were friends.