IN 1989, PUBLISHER Nick Robinson decided to create a companion volume to Gardner Dozois’ excellent The Year’s Best Science Fiction series (retitled Best New SF for the UK market).

So when he asked me if I would be interested in editing an annual “Year’s Best” horror anthology, containing a selection of stories chosen from those initially published in the preceding year, I immediately agreed. However, I had a couple of stipulations.

The first was that I ask Ramsey Campbell – in my opinion one of the most intelligent and knowledgeable authors in the horror field – to co-edit the book with me. The second was that I check first that it was okay with my old friend Karl Edward Wagner, who was currently editing The Year’s Best Horror Stories series for DAW Books. (Ellen Datlow and Terri Windling had started The Year’s Best Fantasy and Horror for St Martin’s Press a couple of years previously, but I did not consider that direct competition as half the book was made up of fantasy stories.) Karl graciously gave us his blessing (which is why the first volume was dedicated to him), and Ramsey and I started reading everything we could get our hands on.

That first volume contained twenty stories, and marked the only time we used tales by Robert Westall and Richard Laymon, who both passed away far too early. Our Introduction, which was an overview of horror in 1989, covered just seven pages, and Kim Newman and I carried our Necrology column over from the defunct film magazine Shock Xpress. It ran one page longer than the Introduction.

In our summation, Ramsey and I expressed concern that the 1980s horror boom could not be sustained and, to survive, the genre would have to move out of the mid-list category. In retrospect, we were depressingly prescient.

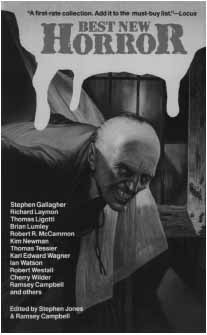

For the cover, the publisher chose Les Edwards’ iconic painting of “The Croglin Vampire” (if you want to see where Buffy the Vampire Slayer got its inspiration from for The Gentlemen in the classic “Hush” episode, look no further). The only thing Robinson did not have was a logo, so I quickly knocked up a concept using a sheet of Letraset transfer lettering. Tomy surprise, they used it on the final book.

In the UK, Robinson Publishing issued that first volume of Best New Horror in trade paperback with gold foil on the cover. For the US, Carroll & Graf decided to do it as a hardcover (without the foil), which they then reprinted as a trade paperback the following year.

When it came to selecting a story from that inaugural edition, it was not difficult. For me, Brian Lumley’s “No Sharks in the Med” has always been a powerful slice of psychological (as opposed to supernatural) horror, and a perfect example of one of my favourite sub-genres – the “fish out of water” tourist who stumbles into a situation over which they have no control . . .

CUSTOMS WAS NON-EXISTENT; people bring duty frees out of Greece, not in. As for passport control: a pair of tanned, hairy, bored-looking characters in stained, too-tight uniforms and peaked caps were in charge. One to take your passport, find the page to be franked, scan photograph and bearer both with a blank gaze that took in absolutely nothing unless you happened to be female and stacked (in which case it took in everything and more), then pass the passport on. Geoff Hammond thought: I wonder if that’s why they call them passports? The second one took the little black book from the first and hammered down on it with his stamp, impressing several pages but no one else, then handed the important document back to its owner – but grudgingly, as if he didn’t believe you could be trusted with it.

This second one, the one with the rubber stamp, had a brother. They could be, probably were, twins. Five-eightish, late twenties, lots of shoulders and no hips; raven hair shiny with grease, so tightly curled it looked permed; brown eyes utterly vacant of expression. The only difference was the uniform: the fact that the brother on the home-and-dry side of the barrier didn’t have one. Leaning on the barrier, he twirled cheap, yellow-framed, dark-lensed glasses like glinting propellers, observed almost speculatively the incoming holidaymakers. He wore shorts, frayed where they hugged his thick thighs, barely long enough to be decent. Hung like a bull! Geoff thought. It was almost embarrassing. Dressed for the benefit of the single girls, obviously. He’d be hoping they were taking notes for later. His chances might improve if he were two inches taller and had a face. But he didn’t; the face was as vacant as the eyes.

Then Geoff saw what it was that was wrong with those eyes: beyond the barrier, the specimen in the bulging shorts was wall-eyed. Likewise his twin punching the passports. Their right eyes had white pupils that stared like dead fish. The one in the booth wore lightly-tinted glasses, so that you didn’t notice until he looked up and stared directly at you. Which in Geoff’s case he hadn’t; but he was certainly looking at Gwen. Then he glanced at Geoff, patiently waiting, and said: “Together, you?” His voice was a shade too loud, making it almost an accusation.

Different names on the passports, obviously! But Geoff wasn’t going to stand here and explain how they were just married and Gwen hadn’t had time to make the required alterations. That really would be embarrassing! In fact (and come to think of it), it might not even be legal. Maybe she should have changed it right away, or got something done with it, anyway, in London. The honeymoon holiday they’d chosen was one of those get-it-while-it’s-going deals, a last-minute half-price seat-filler, a gift horse; and they’d been pushed for time. But what the hell – this was 1987, wasn’t it?

“Yes,” Geoff finally answered. “Together.”

“Ah!” the other nodded, grinned, appraised Gwen again with a raised eyebrow, before stamping her passport and handing it over.

Wall-eyed bastard! Geoff thought.

When they passed through the gate in the barrier, the other wall-eyed bastard had disappeared . . .

Stepping through the automatic glass doors from the shade of the airport building into the sunlight of the coach terminus was like opening the door of a furnace; it was a replay of the moment when the plane’s air-conditioned passengers trooped out across the tarmac to board the buses waiting to convey them to passport control. You came out into the sun fairly crisp, but by the time you’d trundled your luggage to the kerbside and lifted it off the trolley your armpits were already sticky. One o’clock, and the temperature must have been hovering around eighty-five for hours. It not only beat down on you but, trapped in the concrete, beat up as well. Hammerblows of heat.

A mini-skirted courier, English as a rose and harassed as hell – her white blouse soggy while her blue and white hat still sat jaunty on her head – came fluttering, clutching her millboard with its bulldog clip and thin sheaf of notes. “Mr Hammond and Miss—” she glanced at her notes, “—Pinter?”

“Mr and Mrs Hammond,” Geoff answered. He lowered his voice and continued confidentially: “We’re all proper, legitimate, and true. Only our identities have been altered in order to protect our passports.”

“Um?” she said.

Too deep for her, Geoff thought, sighing inwardly.

“Yes,” said Gwen, sweetly. “We’re the Hammonds.”

“Oh!” the girl looked a little confused. “It’s just that—”

“I haven’t changed my passport yet,” said Gwen, smiling.

“Ah!” Understanding finally dawned. The courier smiled nervously at Geoff, turned again to Gwen. “Is it too late for congratulations?”

“Four days,” Gwen answered.

“Well, congratulations anyway.”

Geoff was eager to be out of the sun. “Which is our coach?” he wanted to know. “Is it – could it possibly be – air-conditioned?” There were several coaches parked in an untidy cluster a little further up the kerb.

Again the courier’s confusion, also something of embarrassment showing in her bright blue eyes. “You’re going to – Achladi?”

Geoff sighed again, this time audibly. It was her business to know where they were going. It wasn’t a very good start.

“Yes,” she cut in quickly, before he or Gwen could comment. “Achladi – but not by coach! You see, your plane was an hour late; the coach for Achladi couldn’t be held up for just one couple; but it’s okay – you’ll have the privacy of your own taxi, and of course Skymed will foot the bill.”

She went off to whistle up a taxi and Geoff and Gwen glanced at each other, shrugged, sat down on their cases. But in a moment the courier was back, and behind her a taxi came rolling, nosing into the kerb. Its driver jumped out, whirled about opening doors, the boot, stashing cases while Geoff and Gwen got into the back of the car. Then, throwing his straw hat down beside him as he climbed into the driving seat and slammed his door, the young Greek looked back at his passengers and smiled. A single gold tooth flashed in a bar of white. But the smile was quite dead, like the grin of a shark before he bites, and the voice when it came was phlegmy, like pebbles colliding in mud. “Achladi, yes?”

“Ye—” Geoff began, paused, and finished: “—es! Er, Achladi, right!” Their driver was the wall-eyed passport-stamper’s wall-eyed brother.

“I Spiros,” he declared, turning the taxi out of the airport. “And you?”

Something warned Geoff against any sort of familiarity with this one. In all this heat, the warning was like a breath of cold air on the back of his neck. “I’m Mr Hammond,” he answered, stiffly. “This is my wife.” Gwen turned her head a little and frowned at him.

“I’m—” she began.

“My wife!” Geoff said again. She looked surprised but kept her peace.

Spiros was watching the road where it narrowed and wound. Already out of the airport, he skirted the island’s main town and raced for foothills rising to a spine of half-clad mountains. Achladi was maybe half an hour away, on the other side of the central range. The road soon became a track, a thick layer of dust over pot-holed tarmac and cobbles; in short, a typical Greek road. They slowed down a little through a village where white-walled houses lined the way, with lemon groves set back between and behind the dwellings, and were left with bright flashes of bougainvillea-framed balconies burning like after-images on their retinas. Then Spiros gave it the gun again.

Behind them, all was dust kicked up by the spinning wheels and the suction of the car’s passing. Geoff glanced out of the fly-specked rear window. The cloud of brown dust, chasing after them, seemed ominous in the way it obscured the so-recent past. And turning front again, Geoff saw that Spiros kept his strange eye mainly on the road ahead, and the good one on his rearview. But watching what? The dust? No, he was looking at . . .

At Gwen! The interior mirror was angled directly into her cleavage.

They had been married only a very short time. The day when he’d take pride in the jealousy of other men – in their coveting his wife – was still years in the future. Even then, look but don’t touch would be the order of the day. Right now it was watch where you’re looking, and possession was ninety-nine point nine per cent of the law. As for the other point one per cent: well, there was nothing much you could do about what the lecherous bastards were thinking!

Geoff took Gwen’s elbow, pulled her close and whispered: “Have you noticed how tight he takes the bends? He does it so we’ll bounce about a bit. He’s watching how your tits jiggle!”

She’d been delighting in the scenery, hadn’t even noticed Spiros, his eyes or anything. For a beautiful girl of twenty-three, she was remarkably naïve, and it wasn’t just an act. It was one of the things Geoff loved best about her. Only eighteen months her senior, Geoff hardly considered himself a man of the world; but he did know a rat when he smelled one. In Spiros’s case he could smell several sorts.

“He . . . what—?” Gwen said out loud, glancing down at herself. One button too many had come open in her blouse, showing the edges of her cups. Green eyes widening, she looked up and spotted Spiros’s rearview. He grinned at her through the mirror and licked his lips, but without deliberation. He was naïve, too, in his way. In his different sort of way.

“Sit over here,” said Geoff out loud, as she did up the offending button and the one above it. “The view is much better on this side.” He half-stood, let her slide along the seat behind him. Both of Spiros’ eyes were now back on the road . . .

Ten minutes later they were up into a pass through gorgeous pine-clad slopes so steep they came close to sheer. Here and there scree slides showed through the greenery, or a thrusting outcrop of rock. “Mountains,” Spiros grunted, without looking back.

“You have an eye for detail,” Geoff answered.

Gwen gave his arm a gentle nip, and he knew she was thinking sarcasm is the lowest form of wit – and it doesn’t become you! Nor cruelty, apparently. Geoff had meant nothing special by his “eye” remark, but Spiros was sensitive. He groped in the glove compartment for his yellow-rimmed sunshades, put them on. And drove in a stony silence for what looked like being the rest of the journey.

Through the mountains they sped, and the west coast of the island opened up like a gigantic travel brochure. The mountains seemed to go right down to the sea, rocks merging with that incredible, aching blue. And they could see the village down there, Achladi, like something out of a dazzling dream perched on both sides of a spur that gentled into the ocean.

“Beautiful!” Gwen breathed.

“Yes,” Spiros nodded. “Beautiful, thee village.” Like many Greeks speaking English, his definite articles all sounded like thee. “For fish, for thee swims, thee sun – is beautiful.”

After that it was all downhill; winding, at times precipitous, but the view was never less than stunning. For Geoff, it brought back memories of Cyprus. Good ones, most of them, but one bad one that always made him catch his breath, clench his fists. The reason he hadn’t been too keen on coming back to the Med in the first place. He closed his eyes in an attempt to force the memory out of mind, but that only made it worse, the picture springing up that much clearer.

He was a kid again, just five years old, late in the summer of ’67. His father was a Staff-Sergeant Medic, his mother with the QARANCs; both of them were stationed at Dhekelia, a Sovereign Base Area garrison just up the coast from Larnaca where they had a married quarter. They’d met and married in Berlin, spent three years there, then got posted out to Cyprus together. With two years done in Cyprus, Geoff’s father had a year to go to complete his twenty-two. After that last year in the sun . . . there was a place waiting for him in the ambulance pool of one of London’s big hospitals. Geoff’s mother had hoped to get on the nursing staff of the same hospital. But before any of that . . .

Geoff had started school in Dhekelia, but on those rare weekends when both of his parents were free of duty, they’d all go off to the beach together. And that had been his favourite thing in all the world: the beach with its golden sand and crystal-clear, safe, shallow water. But sometimes, seeking privacy, they’d take a picnic basket and drive east along the coast until the road became a track, then find a way down the cliffs and swim from the rocks up around Cape Greco. That’s where it had happened.

“Geoff!” Gwen tugged at his arm, breaking the spell. He was grateful to be dragged back to reality. “Were you sleeping?”

“Daydreaming,” he answered.

“Me, too!” she said. “I think I must be. I mean, just look at it!”

They were winding down a steep ribbon of road cut into the mountain’s flank, and Achladi was directly below them. A coach coming up squeezed by, its windows full of brown, browned-off faces. Holidaymakers going off to the airport, going home. Their holidays were over but Geoff’s and Gwen’s was just beginning, and the village they had come to was truly beautiful. Especially beautiful because it was unspoiled. This was only Achladi’s second season; before they’d built the airport you could only get here by boat. Very few had bothered.

Geoff’s vision of Cyprus and his bad time quickly receded; while he didn’t consider himself a romantic like Gwen, still he recognized Achladi’s magic. And now he supposed he’d have to admit that they’d made the right choice.

White-walled gardens; red tiles, green-framed windows, some flat roofs and some with a gentle pitch; bougainvillea cascading over white, arched balconies; a tiny white church on the point of the spur where broken rocks finally tumbled into the sea; massive ancient olive trees in walled plots at every street junction, and grapevines on trellises giving a little shade and dappling every garden and patio. That, at a glance, was Achladi. A high sea wall kept the sea at bay, not that it could ever be a real threat, for the entire front of the village fell within the harbour’s crab’s-claw moles. Steps went down here and there from the sea wall to the rocks; a half-dozen towels were spread wherever there was a flat or gently-inclined surface to take them, and the sea bobbed with a half-dozen heads, snorkels and face-masks. Deep water here, but a quarter-mile to the south, beyond the harbour wall, a shingle beach stretched like the webbing between the toes of some great beast for maybe a hundred yards to where a second claw-like spur came down from the mountains. As for the rest of this western coastline: as far as the eye could see both north and south, it looked like sky, cliff and sea to Geoff. Cape Greco all over again. But before he could go back to that:

“Is Villa Eleni, yes?” Spiros’s gurgling voice intruded. “Him have no road. No can drive. I carry thee bags.”

The road went right down the ridge of the spur to the little church. Half-way, it was crossed at right-angles by a second motor road which contained and serviced a handful of shops. The rest of the place was made up of streets too narrow or too perpendicular for cars. A few ancient scooters put-putted and sputtered about, donkeys clip-clopped here and there, but that was all. Spiros turned his vehicle about at the main junction (the only real road junction) and parked in the shade of a giant olive tree. He went to get the luggage. There were two large cases, two small ones. Geoff would have shared the load equally but found himself brushed aside; Spiros took the elephant’s share and left him with the small-fry. He wouldn’t have minded, but it was obviously the Greek’s chance to show off his strength.

Leading the way up a steep cobbled ramp of a street, Spiros’s muscular buttocks kept threatening to burst through the thin stuff of his cut-down jeans. And because the holidaymakers followed on a little way behind, Geoff was aware of Gwen’s eyes on Spiros’s tanned, gleaming thews. There wasn’t much of anywhere else to look. “Him Tarzan, you Jane,” he commented, but his grin was a shade too dry.

“Who you?” she answered, her nose going up in the air. “Cheetah?”

“Uph, uph!” said Geoff.

“Anyway,” she relented. “Your bottom’s nicer. More compact.”

He saved his breath, made no further comment. Even the light cases seemed heavy. If he was Cheetah, that must make Spiros Kong! The Greek glanced back once, grinned in his fashion, and kept going. Breathing heavily, Geoff and Gwen made an effort to catch up, failed miserably. Then, toward the top of the way Spiros turned right into an arched alcove, climbed three stone steps, put down his cases and paused at a varnished pine door. He pulled on a string to free the latch, shoved the door open and took up his cases again. As the English couple came round the corner he was stepping inside. “Thee Villa Eleni,” he said, as they followed him in.

Beyond the door was a high-walled courtyard of black and white pebbles laid out in octopus and dolphin designs. A split-level patio fronted the “villa”, a square box of a house whose one redeeming feature had to be a retractable sun-awning shading the windows and most of the patio. It also made an admirable refuge from the dazzling white of everything.

There were whitewashed concrete steps climbing the side of the building to the upper floor, with a landing that opened onto a wooden-railed balcony with its own striped awning. Beach towels and an outsize lady’s bathing costume were hanging over the rail, drying, and all the windows were open. Someone was home, maybe. Or maybe sitting in a shady taverna sipping on iced drinks. Downstairs, a key with a label had been left in the keyhole of a louvred, fly-screened door. Geoff read the label, which said simply: “Mr Hammond”. The booking had been made in his name.

“This is us,” he said to Gwen, turning the key.

They went in, Spiros following with the large cases. Inside, the cool air was a blessing. Now they would like to explore the place on their own, but the Greek was there to do it for them. And he knew his way around. He put the cases down, opened his arms to indicate the central room. “For sit, talk, thee resting.” He pointed to a tiled area in one corner, with a refrigerator, sink-unit and two-ring electric cooker. “For thee toast, coffee – thee fish and chips, eh?” He shoved open the door of a tiny room tiled top to bottom, containing a shower, wash-basin and WC. “And this one,” he said, without further explanation. Then five strides back across the floor took him to another room, low-ceilinged, pine-beamed, with a Lindean double bed built in under louvred windows. He cocked his head on one side. “And thee bed – just one . . .”

“That’s all we’ll need,” Geoff answered, his annoyance building.

“Yes,” Gwen said. “Well, thank you, er, Spiros – you’re very kind. And we’ll be fine now.”

Spiros scratched his chin, went back into the main room and sprawled in an easy chair. “Outside is hot,” he said. “Here she is cool – chrio, you know?”

Geoff went to him. “It’s very hot,” he agreed, “and we’re sticky. Now we want to shower, put our things away, look around. Thanks for your help. You can go now.”

Spiros stood up and his face went slack, his expression more blank than before. His wall-eye looked strange through its tinted lens. “Go now?” he repeated.

Geoff sighed. “Yes, go!”

The corner of Spiros’s mouth twitched, drew back a little to show his gold tooth. “I fetch from airport, carry cases.”

“Ah!” said Geoff, getting out his wallet. “What do I owe you?” He’d bought drachmas at the bank in London.

Spiros sniffed, looked scornful, half-turned away. “One thousand,” he finally answered, bluntly.

“That’s about four pounds and fifty pence,” Gwen said from the bedroom doorway. “Sounds reasonable.”

“Except it was supposed to be on Skymed,” Geoff scowled. He paid up anyway and saw Spiros to the door. The Greek departed, sauntered indifferently across the patio to pause in the arched doorway and look back across the courtyard. Gwen had come to stand beside Geoff in the double doorway under the awning.

The Greek looked straight at her and licked his fleshy lips. The vacant grin was back on his face. “I see you,” he said, nodding with a sort of slow deliberation.

As he closed the door behind him, Gwen muttered, “Not if I see you first! Ugh!”

“I am with you,” Geoff agreed. “Not my favourite local character!”

“Spiros,” she said. “Well, and it suits him to a tee. It’s about as close as you can get to spider! And that one is about as close as you can get!”

They showered, fell exhausted on the bed – but not so exhausted that they could just lie there without making love.

Later – with suitcases emptied and small valuables stashed out of sight, and spare clothes all hung up or tucked away – dressed in light, loose gear, sandals, sunglasses, it was time to explore the village. “And afterwards,” Gwen insisted, “we’re swimming!” She’d packed their towels and swimwear in a plastic beach bag. She loved to swim, and Geoff might have, too, except . . .

But as they left their rooms and stepped out across the patio, the varnished door in the courtyard wall opened to admit their upstairs neighbours, and for the next hour all thoughts of exploration and a dip in the sea were swept aside. The elderly couple who now introduced themselves gushed, there was no other way to describe it. He was George and she was Petula.

“My dear,” said George, taking Gwen’s hand and kissing it, “such a stunning young lady, and how sad that I’ve only two days left in which to enjoy you!” He was maybe sixty-four or five, ex-handsome but sagging a bit now, tall if a little bent, and brown as a native. With a small grey moustache and faded blue eyes, he looked as if he’d – no, in all probability he had – piloted Spitfires in World War II! Alas, he wore the most blindingly colourful shorts and shirt that Gwen had ever seen.

Petula was very large, about as tall as George but two of him in girth. She was just as brown, though, (and so presumably didn’t mind exposing it all), seemed equally if not more energetic, and was never at a loss for words. They were a strange, paradoxical pair: very upper-crust, but at the same time very much down to earth. If Petula tended to speak with plums in her mouth, certainly they were of a very tangy variety.

“He’ll flatter you to death, my dear,” she told Gwen, ushering the newcomers up the steps at the side of the house and onto the high balcony. “But you must never take your eyes off his hands! Stage magicians have nothing on George. Forty years ago he magicked himself into my bedroom, and he’s been there ever since!”

“She seduced me!” said George, bustling indoors.

“I did not!” Petula was petulant. “What? Why he’s quite simply a wolf in . . . in a Joseph suit!”

“A Joseph suit?” George repeated her. He came back out onto the balcony with brandy-sours in a frosted jug, a clattering tray of ice-cubes, slices of sugared lemon and an eggcup of salt for the sours. He put the lot down on a plastic table, said: “Ah! – glasses!” and ducked back inside again.

“Yes,” his wife called after him, pointing at his Bermudas and Hawaiian shirt. “Your clothes of many colours!”

It was all good fun and Geoff and Gwen enjoyed it. They sat round the table on plastic chairs, and George and Petula entertained them. It made for a very nice welcome to Achladi indeed.

“Of course,” said George after a while, when they’d settled down a little, “we first came here eight years ago, when there were no flights, just boats. Now that people are flying in—” he shrugged, “—two more seasons and there’ll be belly-dancers and hotdog stands! But for now it’s . . . just perfect. Will you look at that view?”

The view from the balcony was very fetching. “From up here we can see the entire village,” said Gwen. “You must point out the best shops, the bank or exchange or whatever, all the places we’ll need to know about.”

George and Petula looked at each other, smiled knowingly.

“Oh?” said Gwen.

Geoff checked their expressions, nodded, made a guess: “There are no places we need to know about.”

“Well, three, actually,” said Petula. “Four if you count Dimi’s – the taverna. Oh, there are other places to eat, but Dimi’s is the place. Except I feel I’ve spoilt it for you now. I mean, that really is something you should have discovered for yourself. It’s half the fun, finding the best place to eat!”

“What about the other three places we should know about?” Gwen inquired. “Will knowing those spoil it for us, too? Knowing them in advance, I mean?”

“Good Lord, no!” George shook his head. “Vital knowledge, young lady!”

“The baker’s,” said Petula. “For fresh rolls – daily.” She pointed it out, blue smoke rising from a cluster of chimneypots. “Also the booze shop, for booze—”

“—Also daily,” said George, pointing. “Right there on that corner – where the bottles glint. D’you know, they have an ancient Metaxa so cheap you wouldn’t—”

“And,” Petula continued, “the path down to the beach. Which is . . . over there.”

“But tell us,” said George, changing the subject, “are you married, you two? Or is that too personal?”

“Oh, of course they’re married!” Petula told him. “But very recently, because they still sit so close together. Touching. You see?”

“Ah!” said George. “Then we shan’t have another elopement.”

“You know, my dear, you really are an old idiot,” said Petula, sighing. “I mean, elopements are for lovers to be together. And these two already are together!”

Geoff and Gwen raised their eyebrows. “An elopement?” Gwen said. “Here? When did this happen?”

“Right here, yes,” said Petula. “Ten days ago. On our first night we had a young man downstairs, Gordon. On his own. He was supposed to be here with his fiancée but she’s jilted him. He went out with us, had a few too many in Dimi’s and told us all about it. A Swedish girl – very lovely, blonde creature – was also on her own. She helped steer him back here and, I suppose, tucked him in. She had her own place, mind you, and didn’t stay.”

“But the next night she did!” George enthused.

“And then they ran off,” said Petula, brightly. “Eloped! As simple as that. We saw them once, on the beach, the next morning. Following which—”

“—Gone!” said George.

“Maybe their holidays were over and they just went home,” said Gwen, reasonably.

“No,” George shook his head. “Gordon had come out on our plane, his holiday was just starting. She’d been here about a week and a half, was due to fly out the day after they made off together.”

“They paid for their holidays and then deserted them?” Geoff frowned. “Doesn’t make any sense.”

“Does anything, when you’re in love?” Petula sighed.

“The way I see it,” said George, “they fell in love with each other, and with Greece, and went off to explore all the options.”

“Love?” Gwen was doubtful. “On the rebound?”

“If she’d been a mousey little thing, I’d quite agree,” said Petula. “But no, she really was a beautiful girl.”

“And him a nice lad,” said George. “A bit sparse but clean, good-looking.”

“Indeed, they were much like you two,” his wife added. “I mean, not like you, but like you.”

“Cheers,” said Geoff, wryly. “I mean, I know I’m not Mr Universe, but—”

“Tight in the bottom!” said Petula. “That’s what the girls like these days. You’ll do all right.”

“See,” said Gwen, nudging him. “Told you so!”

But Geoff was still frowning. “Didn’t anyone look for them? What if they’d been involved in an accident or something?”

“No,” said Petula. “They were seen boarding a ferry in the main town. Indeed, one of the local taxi drivers took them there. Spiros.”

Gwen and Geoff’s turn to look at each other. “A strange fish, that one,” said Geoff.

George shrugged. “Oh, I don’t know. You know him, do you? It’s that eye of his which makes him seem a bit sinister . . .”

Maybe he’s right, Geoff thought.

Shortly after that, their drinks finished, they went off to start their explorations . . .

The village was a maze of cobbled, whitewashed alleys. Even as tiny as it was you could get lost in it, but never for longer than the length of a street. Going downhill, no matter the direction, you’d come to the sea. Uphill you’d come to the main road, or if you didn’t, then turn the next corner and continue uphill, and then you would. The most well-trodden alley, with the shiniest cobbles, was the one that led to the hard-packed path, which in turn led to the beach. Pass the “booze shop” on the corner twice, and you’d know where it was always. The window was plastered with labels, some familiar and others entirely conjectural; inside, steel shelving went floor to ceiling, stacked with every conceivable brand; even the more exotic and (back home) wildly expensive stuffs were on view, often in ridiculously cheap, three-litre, duty-free bottles with their own chrome taps and display stands.

“Courvoisier!” said Gwen, appreciatively.

“Grand Marnier, surely!” Geoff protested. “What, five pints of Grand Marnier? At that price? Can you believe it? But that’s to take home. What about while we’re here?”

“Coconut liqueur,” she said. “Or better still, mint chocolate – to complement our midnight coffees.”

They found several small tavernas, too, with people seated outdoors at tiny tables under the vines. Chicken portions and slabs of lamb sputtering on spits; small fishes sizzling over charcoal; moussaka steaming in long trays . . .

Dimi’s was down on the harbour, where a wide, low wall kept you safe from falling in the sea. They had a Greek salad which they divided two ways, tiny cubes of lamb roasted on wooden slivers, a half-bottle of local white wine costing pennies. As they ate and sipped the wine, so they began to relax; the hot sunlight was tempered by an almost imperceptible breeze off the sea.

Geoff said: “Do you really feel energetic? Damned if I do.”

She didn’t feel full of boundless energy, no, but she wasn’t going down without a fight. “If it was up to you,” she said, “we’d just sit here and watch the fishing nets dry, right?”

“Nothing wrong with taking it easy,” he answered. “We’re on holiday, remember?”

“Your idea of taking it easy means being bone idle!” she answered. “I say we’re going for a dip, then back to the villa for siesta and you know, and—”

“Can we have the you know before the siesta?” He kept a straight face.

“—And then we’ll be all settled in, recovered from the journey, ready for tonight. Insatiable!”

“Okay,” he shrugged. “Anything you say. But we swim from the beach, not from the rocks.”

Gwen looked at him suspiciously. “That was almost too easy.”

Now he grinned. “It was the thought of, well, you know, that did it,” he told her . . .

Lying on the beach, panting from their exertions in the sea, with the sun lifting the moisture off their still-pale bodies, Gwen said: “I don’t understand.”

“Hmm?”

“You swim very well. I’ve always thought so. So what is this fear of the water you complain about?”

“First,” Geoff answered, “I don’t swim very well. Oh, for a hundred yards I’ll swim like a dolphin – any more than that and I do it like a brick! I can’t float. If I stop swimming I sink.”

“So don’t stop.”

“When you get tired, you stop.”

“What was it that made you frightened of the water?” He told her:

“I was a kid in Cyprus. A little kid. My father had taught me how to swim. I used to watch him diving off the rocks, oh, maybe twenty or thirty feet high, into the sea. I thought I could do it, too. So one day when my folks weren’t watching, I tried. I must have hit my head on something on the way down. Or maybe I simply struck the water all wrong. When they spotted me floating in the sea, I was just about done for. My father dragged me out. He was a medic – the kiss of life and all that. So now I’m not much for swimming, and I’m absolutely nothing for diving! I will swim – for a splash, in shallow water, like today – but that’s my limit. And I’ll only go in from a beach. I can’t stand cliffs, height. It’s as simple as that. You married a coward. So there.”

“No I didn’t,” she said. “I married someone with a great bottom. Why didn’t you tell me all this before?”

“You didn’t ask me. I don’t like to talk about it because I don’t much care to remember it. I was just a kid, and yet I knew I was going to die. And I knew it wouldn’t be nice. I still haven’t got it out of my system, not completely. And so the less said about it the better.”

A beach ball landed close by, bounced, rolled to a standstill against Gwen’s thigh. They looked up. A brown, burly figure came striding. They recognized the frayed, bulging shorts. Spiros.

“Hallo,” he said, going down into a crouch close by, forearms resting on his knees. “Thee beach. Thee ball. I swim, play. You swim?” (This to Geoff.) “You come swim, throwing thee ball?”

Geoff sat up. There were half-a-dozen other couples on the beach; why couldn’t this jerk pick on them? Geoff thought to himself: I’m about to get sand kicked in my face! “No,” he said out loud, shaking his head. “I don’t swim much.”

“No swim? You frighting thee big fish? Thee sharks?”

“Sharks?” Now Gwen sat up. From behind their dark lenses she could feel Spiros’s eyes crawling over her.

Geoff shook his head. “There are no sharks in the Med,” he said.

“Him right,” Spiros laughed high-pitched, like a woman, without his customary gurgling. A weird sound. “No sharks. I make thee jokes!” He stopped laughing and looked straight at Gwen. She couldn’t decide if he was looking at her face or her breasts. Those damned sunglasses of his! “You come swim, lady, with Spiros? Play in thee water?”

“My . . . God!” Gwen sputtered, glowering at him. She pulled her dress on over her still-damp, very skimpy swimming costume, packed her towel away, picked up her sandals. When she was annoyed, she really was annoyed.

Geoff stood up as she made off, turned to Spiros. “Now listen—” he began.

“Ah, you go now! Is Okay. I see you.” He took his ball, raced with it down the beach, hurled it out over the sea. Before it splashed down he was diving, low and flat, striking the water like a knife. Unlike Geoff, he swam very well indeed . . .

When Geoff caught up with his wife she was stiff with anger. Mainly angry with herself. “That was so rude of me!” she exploded.

“No it wasn’t,” he said. “I feel exactly the same about it.”

“But he’s so damned . . . persistent! I mean, he knows we’re together, man and wife . . . ‘thee bed – just one.’ How dare he intrude?”

Geoff tried to make light of it. “You’re imagining it,” he said.

“And you? Doesn’t he get on your nerves?”

“Maybe I’m imagining it too. Look, he’s Greek – and not an especially attractive specimen. Look at it from his point of view. All of a sudden there’s a gaggle of dolly-birds on the beach, dressed in stuff his sister wouldn’t wear for undies! So he tries to get closer – for a better view, as it were – so that he can get a wall-eyeful. He’s no different to other blokes. Not quite as smooth, that’s all.”

“Smooth!” she almost spat the word out. “He’s about as smooth as a badger’s—”

“—Bottom,” said Geoff. “Yes, I know. If I’d known you were such a bum-fancier I mightn’t have married you.”

And at last she laughed, but shakily.

They stopped at the booze shop and bought brandy and a large bottle of Coca-Cola. And mint chocolate liqueur, of course, for their midnight coffees . . .

That night Gwen put on a blue and white dress, very Greek if cut a little low in the front, and silver sandals. Tucking a handkerchief into the breast pocket of his white jacket, Geoff thought: she’s beautiful! With her heart-shaped face and the way her hair framed it, cut in a page-boy style that suited its shiny black sheen – and her green, green eyes – he’d always thought she looked French. But tonight she was definitely Greek. And he was so glad that she was English, and his.

Dimi’s was doing a roaring trade. George and Petula had a table in the corner, overlooking the sea. They had spread themselves out in order to occupy all four seats, but when Geoff and Gwen appeared they waved, called them over. “We thought you’d drop in,” George said, as they sat down. And to Gwen: “You look charming, my dear.”

“Now I feel I’m really on my holidays,” Gwen smiled.

“Honeymoon, surely,” said Petula.

“Shh!” Geoff cautioned her. “In England they throw confetti. Over here it’s plates!”

“Your secret is safe with us,” said George.

“Holiday, honeymoon, whatever,” said Gwen. “Compliments from handsome gentlemen; the stars reflected in the sea; a full moon rising and bouzouki music floating in the air. And—”

“—The mouth-watering smells of good Greek grub!” Geoff cut in. “Have you ordered?” He looked at George and Petula.

“A moment ago,” Petula told him. “If you go into the kitchen there, Dimi will show you his menu – live, as it were. Tell him you’re with us and he’ll make an effort to serve us together. Starter, main course, a pudding – the lot.”

“Good!” Geoff said, standing up. “I could eat the saddle off a donkey!”

“Eat the whole donkey,” George told him. “The one who’s going to wake you up with his racket at six-thirty tomorrow morning.”

“You don’t know Geoff,” said Gwen. “He’d sleep through a Rolling Stones concert.”

“And you don’t know Achladi donkeys!” said Petula.

In the kitchen, the huge, bearded proprietor was busy, fussing over his harassed-looking cooks. As Geoff entered he came over. “Good evenings, sir. You are new in Achladi?”

“Just today,” Geoff smiled. “We came here for lunch but missed you.”

“Ah!” Dimitrios gasped, shrugged apologetically. “I was sleeps! Every day, for two hours, I sleeps. Where you stay, eh?”

“The Villa Eleni.”

“Eleni? Is me!” Dimitrios beamed. “I am Villa Eleni. I mean, I owns it. Eleni is thee name my wifes.”

“It’s a beautiful name,” said Geoff, beginning to feel trapped in the conversation. “Er, we’re with George and Petula.”

“You are eating? Good, good. I show you.” Geoff was given a guided tour of the ovens and the sweets trolley. He ordered, keeping it light for Gwen.

“And here,” said Dimitrios. “For your lady!” He produced a filigreed silver-metal brooch in the shape of a butterfly, with DIMI’S worked into the metal of the body. Gwen wouldn’t like it especially, but politic to accept it. Geoff had noticed several female patrons wearing them, Petula included.

“That’s very kind of you,” he said.

Making his way back to their table, he saw Spiros was there before him.

Now where the hell had he sprung from? And what the hell was he playing at?

Spiros wore tight blue jeans, (his image, obviously), and a white T-shirt stained down the front. He was standing over the corner table, one hand on the wall where it overlooked the sea, the other on the table itself. Propped up, still he swayed. He was leaning over Gwen. George and Petula had frozen smiles on their faces, looked frankly astonished. Geoff couldn’t quite see all of Gwen, for Spiros’s bulk was in the way.

What he could see, of the entire mini-tableau, printed itself on his eyes as he drew closer. Adrenalin surged in him and he began to breathe faster. He barely noticed George standing up and sliding out of view. Then as the bouzouki tape came to an end and the taverna’s low babble of sound seemed to grow that much louder, Gwen’s outraged voice suddenly rose over everything else:

“Get . . . your . . . filthy . . . paws . . . off me!” she cried.

Geoff was there. Petula had drawn as far back as possible; no longer smiling, her hand was at her throat, her eyes staring in disbelief. Spiros’s left hand had caught up the V of Gwen’s dress. His fingers were inside the dress and his thumb outside. In his right hand he clutched a pin like the one Dimitrios had given to Geoff. He was protesting:

“But I giving it! I putting it on your dress! Is nice, this one. We friends. Why you shout? You no like Spiros?” His throaty, gurgling voice was slurred: waves of ouzo fumes literally wafted off him like the stench of a dead fish. Geoff moved in, knocked Spiros’s elbow away where it leaned on the wall. Spiros must release Gwen to maintain his balance. He did so, but still crashed half over the wall. For a moment Geoff thought he would go completely over, into the sea. But he just lolled there, shaking his head, and finally turned it to look back at Geoff. There was a look on his face which Geoff couldn’t quite describe. Drunken stupidity slowly turning to rage, maybe. Then he pushed himself upright, stood swaying against the wall, his fists knotting and the muscles in his arms bunching.

Hit him now, Geoff’s inner man told him. Do it, and he’ll go clean over into the sea. It’s not high, seven or eight feet, that’s all. It’ll sober the bastard up, and after that he won’t trouble you again.

But what if he couldn’t swim? You know he swims like a fish – like a bloody shark!

“You think you better than Spiros, eh?” The Greek wobbled dangerously, steadied up and took a step in Geoff’s direction.

“No!” the voice of the bearded Dimitrios was shattering in Geoff’s ear. Massive, he stepped between them, grabbed Spiros by the hair, half-dragged, half-pushed him toward the exit. “No, everybody thinks he’s better!” he cried. “Because everybody is better! Out—” he heaved Spiros yelping into the harbour’s shadows. “I tell you before, Spiros: drink all the ouzo in Achladi. Is your business. But not let it ruin my business. Then comes thee real troubles!”

Gwen was naturally upset. It spoiled something of the evening for her. But by the time they had finished eating, things were about back to normal. No one else in the place, other than George and Petula, had seemed especially interested in the incident anyway.

At around eleven, when the taverna had cleared a little, the girl from Skymed came in. She came over.

“Hello, Julie!” said George, finding her a chair. And, flatterer born, he added: “How lovely you’re looking tonight – but of course you look lovely all the time.”

Petula tut-tutted. “George, if you hadn’t met me you’d be a gigolo by now, I’m sure!”

“Mr Hammond,” Julie said. “I’m terribly sorry. I should have explained to Spiros that he’d recover the fare for your ride from me. Actually, I believed he understood that but apparently he didn’t. I’ve just seen him in one of the bars and asked him how much I owed him. He was a little upset, wouldn’t accept the money, told me I should see you.”

“Was he sober yet?” Geoff asked, sourly.

“Er, not very, I’m afraid. Has he been a nuisance?”

Geoff coughed. “Only a bit of a one.”

“It was a thousand drachmas” said Gwen.

The courier looked a little taken aback. “Well it should only have been seven hundred.”

“He did carry our bags, though,” said Geoff.

“Ah! Maybe that explains it. Anyway, I’m authorized to pay you seven hundred.”

“All donations are welcome,” Gwen said, opening her purse and accepting the money. “But if I were you, in future I’d use someone else. This Spiros isn’t a particularly pleasant fellow.”

“Well he does seem to have a problem with the ouzo,” Julie answered. “On the other hand—”

“He has several problems!” Geoff was sharper than he meant to be. After all, it wasn’t her fault.

“—He also has the best beach,” Julie finished.

“Beach?” Geoff raised an eyebrow. “He has a beach?”

“Didn’t we tell you?” Petula spoke up. “Two or three of the locals have small boats in the harbour. For a few hundred drachmas they’ll take you to one of a handful of private beaches along the coast. They’re private because no one lives there, and there’s no way in except by boat. The boatmen have their favourite places, which they guard jealously and call ‘their’ beaches, so that the others don’t poach on them. They take you in the morning or whenever, collect you in the evening. Absolutely private . . . ideal for picnics . . . romance!” She sighed.

“What a lovely idea,” said Gwen. “To have a beach of your own for the day!”

“Well, as far as I’m concerned,” Geoff told her, “Spiros can keep his beach.”

“Oh-oh!” said George. “Speak of the devil . . .”

Spiros had returned. He averted his face and made straight for the kitchens in the back. He was noticeably steadier on his feet now. Dimitrios came bowling out to meet him and a few low-muttered words passed between them. Their conversation quickly grew more heated, becoming rapid-fire Greek in moments, and Spiros appeared to be pleading his case. Finally Dimitrios shrugged, came lumbering toward the corner table with Spiros in tow.

“Spiros, he sorry,” Dimitrios said. “For tonight. Too much ouzo. He just want be friendly.”

“Is right,” said Spiros, lifting his head. He shrugged helplessly. “Thee ouzo.”

Geoff nodded. “Okay, forget it,” he said, but coldly.

“Is . . . okay?” Spiros lifted his head a little more. He looked at Gwen.

Gwen forced herself to nod. “It’s okay.”

Now Spiros beamed, or as close as he was likely to get to it. But still Geoff had this feeling that there was something cold and calculating in his manner.

“I make it good!” Spiros declared, nodding. “One day, I take you thee best beach! For thee picnic. Very private. Two peoples, no more. I no take thee money, nothing. Is good?”

“Fine,” said Geoff. “That’ll be fine.”

“Okay,” Spiros smiled his unsmile, nodded, turned away. Going out, he looked back. “I sorry,” he said again; and again his shrug. “Thee ouzo . . .”

“Hardly eloquent,” said Petula, when he’d disappeared.

“But better than nothing,” said George.

“Things are looking up!” Gwen was happier now.

Geoff was still unsure how he felt. He said nothing . . .

“Breakfast is on us,” George announced the next morning. He smiled down on Geoff and Gwen where they drank coffee and tested the early morning sunlight at a garden table on the patio. They were still in their dressing-gowns, eyes bleary, hair tousled.

Geoff looked up, squinting his eyes against the hurtful blue of the sky, and said: “I see what you mean about that donkey! What the hell time is it, anyway?”

“Eight-fifteen,” said George. “You’re lucky. Normally he’s at it, oh, an hour earlier than this!” From somewhere down in the maze of alleys, as if summoned by their conversation, the hideous braying echoed yet again as the village gradually came awake.

Just before nine they set out, George and Petula guiding them to a little place bearing the paint-daubed legend: BREKFAS BAR. They climbed steps to a pine-railed patio set with pine tables and chairs, under a varnished pine frame supporting a canopy of split bamboo. Service was good; the “English” food hot, tasty, and very cheap; the coffee dreadful!

“Yechh!” Gwen commented, understanding now why George and Petula had ordered tea. “Take a note, Mr Hammond,” she said. “Tomorrow, no coffee. Just fruit juice.”

“We thought maybe it was us being fussy,” said Petula. “Else we’d have warned you.”

“Anyway,” George sighed. “Here’s where we have to leave you. For tomorrow we fly – literally. So today we’re shopping, picking up our duty-frees, gifts, the postcards we never sent, some Greek cigarettes.”

“But we’ll see you tonight, if you’d care to?” said Petula.

“Delighted!” Geoff answered. “What, Zorba’s Dance, moussaka, and a couple or three of those giant Metaxas that Dimi serves? Who could refuse?”

“Not to mention the company,” said Gwen.

“About eight-thirty, then,” said Petula. And off they went.

“I shall miss them,” said Gwen.

“But it will be nice to be on our own for once,” Geoff leaned over to kiss her.

“Hallo!” came a now familiar, gurgling voice from below. Spiros stood in the street beyond the rail, looking up at them, the sun striking sparks from the lenses of his sunglasses. Their faces fell and he couldn’t fail to notice it. “Is okay,” he quickly held up a hand. “I no stay. I busy. Today I make thee taxi. Later, thee boat.”

Gwen gave a little gasp of excitement, clutched Geoff’s arm. “The private beach!” she said. “Now that’s what I’d call being on our own!” And to Spiros: “If we’re ready at one o’clock, will you take us to your beach?”

“Of course!” he answered. “At one o’clock, I near Dimi’s. My boat, him called Spiros like me. You see him.”

Gwen nodded. “We’ll see you then.”

“Good!” Spiros nodded. He looked up at them a moment longer, and Geoff wished he could fathom where the man’s eyes were. Probably up Gwen’s dress. But then he turned and went on his way.

“Now we shop!” Gwen said.

They shopped for picnic items. Nothing gigantic, mainly small things. Slices of salami, hard cheese, two fat tomatoes, fresh bread, a bottle of light white wine, some feta, eggs for boiling, and a litre of crystal-clear bottled water. And as an afterthought: half-a-dozen small pats of butter, a small jar of honey, a sharp knife and a packet of doilies. No wicker basket; their little plastic coolbox would have to do. And one of their pieces of shoulder luggage for the blanket, towels, and swim-things. Geoff was no good for details; Gwen’s head, to the contrary, was only happy buzzing with them. He let her get on with it, acted as beast of burden. In fact there was no burden to mention. After all, she was shopping for just the two of them, and it was as good a way as any to explore the village stores and see what was on offer. While she examined this and that, Geoff spent the time comparing the prices of various spirits with those already noted in the booze shop. So the morning passed.

At eleven-thirty they went back to the Villa Eleni for you know and a shower, and afterwards Gwen prepared the foodstuffs while Geoff lazed under the awning. No sign of George and Petula; eighty-four degrees of heat as they idled their way down to the harbour; the village had closed itself down through the hottest part of the day, and they saw no one they knew. Spiros’s boat lolled like a mirrored blot on the stirless ocean, and Geoff thought: even the fish will be finding this a bit much! Also: I hope there’s some shade on this blasted beach!

Spiros appeared from behind a tangle of nets. He stood up, yawned, adjusted his straw hat like a sunshade on his head. “Thee boat,” he said, in his entirely unnecessary fashion, as he helped them climb aboard. Spiros “thee boat” was hardly a hundred per cent seaworthy, Geoff saw that immediately. In fact, in any other ocean in the world she’d be condemned. But this was the Mediterranean in July.

Barely big enough for three adults, the boat rocked a little as Spiros yanked futilely on the starter. Water seeped through boards, rotten and long since sprung, black with constant damp and badly caulked. Spiros saw Geoff’s expression where he sat with his sandals in half an inch of water. He shrugged. “Is nothings,” he said.

Finally the engine coughed into life, began to purr, and they were off. Spiros had the tiller; Geoff and Gwen faced him from the prow, which now lifted up a little as they left the harbour and cut straight out to sea. It was then, for the first time, that Geoff noticed Spiros’s furtiveness: the way he kept glancing back toward Achladi, as if anxious not to be observed. Unlikely that they would be, for the village seemed fast asleep. Or perhaps he was just checking land marks, avoiding rocks or reefs or what have you. Geoff looked overboard. The water seemed deep enough to him. Indeed, it seemed much too deep! But at least there were no sharks . . .

Well out to sea, Spiros swung the boat south and followed the coastline for maybe two and a half to three miles. The highest of Achladi’s houses and apartments had slipped entirely from view by the time he turned in towards land again and sought a bight in the seemingly unbroken march of cliffs. The place was landmarked: a fang of rock had weathered free, shaping a stack that reared up from the water to form a narrow, deep channel between itself and the cliffs proper. In former times a second, greater stack had crashed oceanward and now lay like a reef just under the water across the entire frontage. In effect, this made the place a lagoon: a sandy beach to the rear, safe water, and the reef of shattered, softly matted rocks where the small waves broke.

There was only one way in. Spiros gentled his boat through the deep water between the crooked outcrop and the overhanging cliff. Clear of the channel, he nosed her into the beach and cut the motor; as the keel grated on grit he stepped nimbly between his passengers and jumped ashore, dragging the boat a few inches up onto the sand. Geoff passed him the picnic things, then steadied the boat while Gwen took off her sandals and made to step down where the water met the sand. But Spiros was quick off the mark.

He stepped forward, caught her up, carried her two paces up the beach and set her down. His left arm had been under her thighs, his right under her back, cradling her. But when he set her upon her own feet his right hand had momentarily cupped her breast, which he’d quite deliberately squeezed.

Gwen opened her mouth, stood gasping her outrage, unable to give it words. Geoff had got out of the boat and was picking up their things to bring them higher up the sand. Spiros, slapping him on the back, stepped round him and shoved the boat off, splashed in shallow water a moment before leaping nimbly aboard. Gwen controlled herself, said nothing. She could feel the blood in her cheeks but hoped Geoff wouldn’t notice. Not here, miles from anywhere. Not in this lonely place. No, there must be no trouble here.

For suddenly it had dawned on her just how very lonely it was. Beautiful, unspoiled, a lovers’ idyll – but oh so very lonely . . .

“You all right, love?” said Geoff, taking her elbow. She was looking at Spiros standing silent in his boat. Their eyes seemed locked, it was as if she didn’t see him but the mind behind the sunglasses, behind those disparate, dispassionate eyes. A message had passed between them. Geoff sensed it but couldn’t fathom it. He had almost seemed to hear Spiros say “yes”, and Gwen answer “no”.

“Gwen?” he said again.

“I see you,” Spiros called, grinning. It broke the spell. Gwen looked away, and Geoff called out:

“Six-thirty, right?”

Spiros waggled a hand this way and that palm-down, as if undecided. “Six, six-thirty – something,” he said, shrugging. He started his motor, waved once, chugged out of the bay between the jutting sentinel rock and the cliffs. As he passed out of sight the boat’s engine roared with life, its throaty growl rapidly fading into the distance . . .

Gwen said nothing about the incident; she felt sure that if she did, then Geoff would make something of it. Their entire holiday could so easily be spoiled. It was bad enough that for her the day had already been ruined. So she kept quiet, and perhaps a little too quiet. When Geoff asked her again if anything was wrong she told him she had a headache. Then, feeling a little unclean, she stripped herself quite naked and swam while he explored the beach.

Not that there was a great deal to explore. He walked the damp sand at the water’s rim to the southern extreme and came up against the cliffs where they curved out into the sea. They were quite unscalable, towering maybe eighty or ninety feet to their jagged rim. Walking the hundred or so yards back the other way, the thought came to Geoff that if Spiros didn’t come back for them – that is, if anything untoward should happen to him – they’d just have to sit it out until they were found. Which, since Spiros was the only one who knew they were here, might well be a long time. Having thought it, Geoff tried to shake the idea off but it wouldn’t go away. The place was quite literally a trap. Even a decent swimmer would have to have at least a couple of miles in him before considering swimming out of here.

Once lodged in Geoff’s brain, the concept rapidly expanded itself. Before . . . he had looked at the faded yellow and bone-white facade of the cliffs against the incredible blue of the sky with admiration; the beach had been every man’s dream of tranquility, privacy, Eden with its own Eve; the softly lapping ocean had seemed like a warm, soothing bath reaching from horizon to horizon. But now . . . the place was so like Cape Greco. Except at Greco there had always been a way down to the sea – and up from it . . .

The northern end of the beach was much like the southern, the only difference being the great fang of rock protruding from the sea. Geoff stripped, swam out to it, was aware that the water here was a great deal deeper than back along the beach. But the distance was only thirty feet or so, nothing to worry about. And there were hand and footholds galore around the base of the pillar of upthrusting rock. He hauled himself up onto a tiny ledge, climbed higher (not too high), sat on a projecting fist of rock with his feet dangling and called to Gwen. His voice surprised him, for it seemed strangely small and panting. The cliffs took it up, however, amplified and passed it on. His shout reached Gwen where she splashed; she spotted him, stopped swimming and stood up. She waved, and he marvelled at her body, her tip-tilted breasts displayed where she stood like some lovely Mediterranean nymph, all unashamed. Venus rising from the waves. Except that here the waves were little more than ripples.

He glanced down at the water and was at once dizzy: the way it lapped at the rock and flowed so gently in the worn hollows of the stone, all fluid and glinting motion; and Geoff’s stomach following the same routine, seeming to slosh loosely inside him. Damn this terror of his! What was he but eight, nine feet above the sea? God, he might as well feel sick standing on a thick carpet!

He stood up, shouted, jumped outward, toward Gwen.

Down he plunged into cool, liquid blue, and fought his way to the surface, and swam furiously to the beach. There he lay, half-in, half-out of the water, his heart and lungs hammering, blood coursing through his body. It had been such a little thing – something any ten-year-old child could have done – but to him it had been such an effort. And an achievement!

Elated, he stood up, sprinted down the beach, threw himself into the warm, shallow water just as Gwen was emerging. Carried back by him she laughed, splashed him, finally submitted to his hug. They rolled in twelve inches of water and her legs went round him; and there where the water met the sand they grew gentle, then fierce, and when it was done the sea laved their heat and rocked them gently, slowly dispersing their passion . . .

About four o’clock they ate, but very little. They weren’t hungry; the sun was too hot; the silence, at first enchanting, had turned to a droning, sun-scorched monotony that beat on the ears worse than a city’s roar. And there was a smell. When the light breeze off the sea swung in a certain direction, it brought something unpleasant with it.

To provide shade, Geoff had rigged up his shirt, slacks, and a large beach towel on a frame of drifted bamboo between the brittle, sandpapered branches of an old tree washed halfway up the sand. There in this tatty, makeshift teepee they’d spread their blanket, retreated from the pounding sun. But as the smell came again Geoff crept out of the cramped shade, stood up and shielded his eyes to look along the wall of the cliffs. “It comes . . . from over there,” he said, pointing.

Gwen joined him. “I thought you’d explored?” she said.

“Along the tideline,” he answered, nodding slowly. “Not along the base of the cliffs. Actually, they don’t look too safe, and they overhang a fair bit in places. But if you’ll look where I’m pointing – there, where the cliffs are cut back – is that water glinting?”

“A spring?” she looked at him. “A waterfall?”

“Hardly a waterfall,” he said. “More a dribble. But what is it that’s dribbling? I mean, springs don’t stink, do they?”

Gwen wrinkled her nose. “Sewage, do you think?”

“Yecchh!” he said. “But at least it would explain why there’s no one else here. I’m going to have a look.”

She followed him to the place where the cliffs were notched in a V. Out of the sunlight, they both shivered a little. They’d put on swimwear for simple decency’s sake, in case a boat should pass by, but now they hugged themselves as the chill of damp stone drew off their stored heat and brought goose-pimples to flesh which sun and sea had already roughened. And there, beneath the overhanging cliff, they found in the shingle a pool formed of a steady flow from on high. Without a shadow of a doubt, the pool was the source of the carrion stench; but here in the shade its water was dark, muddied, rippled, quite opaque. If there was anything in it, then it couldn’t be seen.

As for the waterfall: it forked high up in the cliff, fell in twin streams, one of which was a trickle. Leaning out over the pool at its narrowest, shallowest point, Geoff cupped his hand to catch a few droplets. He held them to his nose, shook his head. “Just water,” he said. “It’s the pool itself that stinks.”

“Or something back there?” Gwen looked beyond the pool, into the darkness of the cave formed of the V and the overhang.

Geoff took up a stone, hurled it into the darkness and silence. Clattering echoes sounded, and a moment later—

Flies! A swarm of them, disturbed where they’d been sitting on cool, damp ledges. They came in a cloud out of the cave, sent Geoff and Gwen yelping, fleeing for the sea. Geoff was stung twice, Gwen escaped injury; the ocean was their refuge, shielding them while the flies dispersed or returned to their vile-smelling breeding ground.

After the murky, poisonous pool the sea felt cool and refreshing. Muttering curses, Geoff stood in the shallows while Gwen squeezed the craters of the stings in his right shoulder and bathed them with salt water. When she was done he said, bitterly: “I’ve had it with this place! The sooner the Greek gets back the better.”

His words were like an invocation. Towelling themselves dry, they heard the roar of Spiros’s motor, heard it throttle back, and a moment later his boat came nosing in through the gap between the rock and the cliffs. But instead of landing he stood off in the shallow water. “Hallo,” he called, in his totally unnecessary fashion.

“You’re early,” Geoff called back. And under his breath: Thank God!

“Early, yes,” Spiros answered. “But I have thee troubles.” He shrugged.

Gwen had pulled her dress on, packed the last of their things away. She walked down to the water’s edge with Geoff. “Troubles?” she said, her voice a shade unsteady.

“Thee boat,” he said, and pointed into the open, lolling belly of the craft, where they couldn’t see. “I hitting thee rock when I leave Achladi. Is okay, but—” And he made his fifty-fifty sign, waggling his hand with the fingers open and the palm down. His face remained impassive, however.

Geoff looked at Gwen, then back to Spiros. “You mean it’s unsafe?”

“For three peoples, unsafe – maybe.” Again the Greek’s shrug. “I thinks, I take thee lady first. Is Okay, I come back. Is bad, I find other boat.”

“You can’t take both of us?” Geoff’s face fell.

Spiros shook his head. “Maybe big problems,” he said.

Geoff nodded. “Okay,” he said to Gwen. “Go just as you are. Leave all this stuff here and keep the boat light.” And to Spiros: “Can you come in a bit more?”

The Greek made a clicking sound with his tongue, shrugged apologetically. “Thee boat is broked. I not want thee more breakings. You swim?” He looked at Gwen, leaned over the side and held out his hand. Keeping her dress on, she waded into the water, made her way to the side of the boat. The water only came up to her breasts, but it turned her dress to a transparent, clinging film. She grasped the upper strake with one hand and made to drag herself aboard. Spiros, leaning backwards, took her free hand.

Watching, Geoff saw her come half out of the water – then saw her freeze. She gasped loudly and twisted her wet hand in Spiros’s grasp, tugged free of his grip, flopped back down into the water. And while the Greek regained his balance, she quickly swam back ashore. Geoff helped her from the sea. “Gwen?” he said.

Spiros worked his starter, got the motor going. He commenced a slow, deliberate circling of the small bay.

“Gwen?” Geoff said again. “What is it? What’s wrong?” She was pale, shivering.

“He . . .” she finally started to speak. “He . . . had an erection! Geoff, I could see it bulging in his shorts, throbbing. My God – and I know it was for me! And the boat . . .”

“What about the boat?” Anger was building in Geoff’s heart and head, starting to run cold in his blood.

“There was no damage – none that I could see, anyway. He . . . he just wanted to get me into that boat, on my own!”

Spiros could see them talking together. He came angling close into the beach, called out: “I bring thee better boat. Half-an-hour. Is safer. I see you.” He headed for the channel between the rock and the cliff and in another moment passed from sight . . .

“Geoff, we’re in trouble,” Gwen said, as soon as Spiros had left. “We’re in serious trouble.”

“I know it,” he said. “I think I’ve known it ever since we got here. That bloke’s as sinister as they come.”

“And it’s not just his eye, it’s his mind,” said Gwen. “He’s sick.” Finally, she told her husband about the incident when Spiros had carried her ashore from the boat.

“So that’s what that was all about,” he growled. “Well, something has to be done about him. We’ll have to report him.”

She clutched his arm. “We have to get back to Achladi before we can do that,” she said quietly. “Geoff, I don’t think he intends to let us get back!”

That thought had been in his mind, too, but he hadn’t wanted her to know it. He felt suddenly helpless. The trap seemed sprung and they were in it. But what did Spiros intend, and how could he possibly hope to get away with it – whatever “it” was? Gwen broke into his thoughts:

“No one knows we’re here, just Spiros.”

“I know,” said Geoff. “And what about that couple who . . .” He let it tail off. It had just slipped from his tongue. It was the last thing he’d wanted to say.

“Do you think I haven’t thought of that?” Gwen hissed, gripping his arm more tightly yet. “He was the last one to see them – getting on a ferry, he said. But did they?” She stripped off her dress.

“What are you doing?” he asked, breathlessly.

“We came in from the north,” she answered, wading out again into the water. “There were no beaches between here and Achladi. What about to the south? There are other beaches than this one, we know that. Maybe there’s one just half a mile away. Maybe even less. If I can find one where there’s a path up the cliffs . . .”

“Gwen,” he said. “Gwen!” Panic was rising in him to match his impotence, his rage and terror.

She turned and looked at him, looked helpless in her skimpy bikini – and yet determined, too. And to think he’d considered her naïve! Well, maybe she had been. But no more. She managed a small smile, said, “I love you.”

“What if you exhaust yourself?” He could think of nothing else to say.

“I’ll know when to turn back,” she said. Even in the hot sunlight he felt cold, and knew she must, too. He started towards her, but she was already into a controlled crawl, heading south, out across the submerged rocks. He watched her out of sight round the southern extreme of the jutting cliffs, stood knotting and unknotting his fists at the edge of the sea . . .

For long moments Geoff stood there, cold inside and hot out. And at the same time cold all over. Then the sense of time fleeting by overcame him. He ground his teeth, felt his frustration overflow. He wanted to shout but feared Gwen would hear him and turn back. But there must be something he could do. With his bare hands? Like what? A weapon – he needed a weapon.

There was the knife they’d bought just for their picnic. He went to their things and found it. Only a three-inch blade, but sharp! Hand to hand it must give him something of an advantage. But what if Spiros had a bigger knife? He seemed to have a bigger or better everything else.

One of the drifted tree’s branches was long, straight, slender. It pointed like a mocking, sandpapered wooden finger at the unscalable cliffs. Geoff applied his weight close to the main branch. As he lifted his feet from the ground the branch broke, sending him to his knees in the sand. Now he needed some binding material. Taking his unfinished spear with him, he ran to the base of the cliffs. Various odds and ends had been driven back there by past storms. Plastic Coke bottles, fragments of driftwood, pieces of cork . . . a nylon fishing net tangled round a broken barrel!

Geoff cut lengths of tough nylon line from the net, bound the knife in position at the end of his spear. Now he felt he had a real advantage. He looked around. The sun was sinking leisurely towards the sea, casting his long shadow on the sand. How long since Spiros left? How much time left till he got back? Geoff glanced at the frowning needle of the sentinel rock. A sentinel, yes. A watcher. Or a watchtower!

He put down his spear, ran to the northern point and sprang into the sea. Moments later he was clawing at the rock, dragging himself from the water, climbing. And scarcely a thought of danger, not from the sea or the climb, not from the deep water or the height. At thirty feet the rock narrowed down; he could lean to left or right and scan the sea to the north, in the direction of Achladi. Way out on the blue, sails gleamed white in the brilliant sunlight. On the far horizon, a smudge of smoke. Nothing else.

For a moment – the merest moment – Geoff’s old nausea returned. He closed his eyes and flattened himself to the rock, gripped tightly where his fingers were bedded in cracks in the weathered stone. A mass of stone shifted slightly under the pressure of his right hand, almost causing him to lose his balance. He teetered for a second, remembered Gwen . . . the nausea passed, and with it all fear. He stepped a little lower, examined the great slab of rock which his hand had tugged loose. And suddenly an idea burned bright in his brain.

Which was when he heard Gwen’s cry, thin as a keening wind, shrilling into his bones from along the beach. He jerked his head round, saw her there in the water inside the reef, wearily striking for the shore. She looked all in. His heart leaped into his mouth, and without pause he launched himself from the rock, striking the water feet first and sinking deep. No fear or effort to it this time; no time for any of that; surfacing, he struck for the shore. Then back along the beach, panting his heart out, flinging himself down in the small waves where she kneeled, sobbing, her face covered by her hands.

“Gwen, are you all right? What is it, love? What’s happened? I knew you’d exhaust yourself!”

She tried to stand up, collapsed into his arms and shivered there; he cradled her where earlier they’d made love. And at last she could tell it.

“I . . . I stayed close to the shore,” she gasped, gradually getting her breath. “Or rather, close to the cliffs. I was looking . . . looking for a way up. I’d gone about a third of a mile, I think. Then there was a spot where the water was very deep and the cliffs sheer. Something touched my legs and it was like an electric shock – I mean, it was so unexpected there in that deep water. To feel something slimy touching my legs like that. Ugh!” She drew a deep breath.

“I thought: God, sharks! But then I remembered: there are no sharks in the Med. Still, I wanted to be sure. So . . . so I turned, made a shallow dive and looked to see what . . . what . . .” She broke down into sobbing again.

Geoff could do nothing but warm her, hug her tighter yet.

“Oh, but there are sharks in the Med, Geoff,” she finally went on. “One shark, anyway. His name is Spiros! A spider? No, he’s a shark! Under the sea there, I saw . . . a girl, naked, tethered to the bottom with a rope round her ankle. And down in the deeps, a stone holding her there.”

“My God!” Geoff breathed.

“Her thighs, belly, were covered in those little green swimming crabs. She was all bloated, puffy, floating upright on her own internal gasses. Fish nibbled at her. Her nipples were gone . . .”

“The fish!” Geoff gasped. But Gwen shook her head.

“Not the fish,” she rasped. “Her arms and breasts were black with bruises. Her nipples had been bitten through – right through! Oh, Geoff, Geoff!” She hugged him harder than ever, shivering hard enough to shake him. “I know what happened to her. It was him, Spiros.” She paused, tried to control her shivering, which wasn’t only the after-effect of the water.

And finally she continued: “After that I had no strength. But somehow I made it back.”

“Get dressed,” he told her then, his voice colder than she’d ever heard it. “Quickly! No, not your dress – my trousers, shirt. The slacks will be too long for you. Roll up the bottoms. But get dressed, get warm.”

She did as he said. The sun, sinking, was still hot. Soon she was warm again, and calmer. Then Geoff gave her the spear he’d made and told her what he was going to do . . .

There were two of them, as like as peas in a pod. Geoff saw them, and the pieces fell into place. Spiros and his brother. The island’s codes were tight. These two looked for loose women; loose in their narrow eyes, anyway. And from the passports of the honeymooners it had been plain that they weren’t married. Which had made Gwen a whore, in their eyes. Like the Swedish girl, who’d met a man and gone to bed with him. As easy as that. So Spiros had tried it on, the easy way at first. By making it plain that he was on offer. Now that that hadn’t worked, now it was time for the hard way.

Geoff saw them coming in the boat and stopped gouging at the rock. His fingernails were cracked and starting to bleed, but the job was as complete as he could wish. He ducked back out of sight, hugged the sentinel rock and thought only of Gwen. He had one chance and mustn’t miss it.

He glanced back, over his shoulder. Gwen had heard the boat’s engine. She stood halfway between the sea and the waterfall with its foul pool. Her spear was grasped tightly in her hands. Like a young Amazon, Geoff thought. But then he heard the boat’s motor cut back and concentrated on what he was doing.

The put-put-put of the boat’s exhaust came closer. Geoff took a chance, glanced round the rim of the rock. Here they came, gentling into the channel between the rock and the cliffs. Spiros’s brother wore slacks; both men were naked from the waist up; Spiros had the tiller. And his brother had a shotgun!

One chance. Only one chance.

The boat’s nose came inching forward, began to pass directly below. Geoff gave a mad yell, heaved at the loose wedge of rock. For a moment he thought it would stick and put all his weight into it. But then it shifted, toppled.

Below, the two Greeks had looked up, eyes huge in tanned, startled faces. The one with the shotgun was on his feet. He saw the falling rock in the instant before it smashed down on him and drove him through the bottom of the boat. His gun went off, both barrels, and the shimmering air near Geoff’s head buzzed like a nest of wasps. Then, while all below was still in a turmoil, he aimed himself at Spiros and jumped.