5

Loneliness of the Celebrity

Rousseau is a case both exemplary and exceptional. The author of La Nouvelle Héloïse was not only one of the best known writers in all of Europe during the Enlightenment, arousing curiosity and sometimes spectacular excitement, but he was also one of the first to comment on his own celebrity. Obsessed by the question of his public persona, Rousseau, in his correspondence and his autobiographical texts, engaged in a fascinating reflection, partly social philosophy and partly paranoid delirium, about the consequences of a celebrity that he judged “disastrous.” His career trajectory is particularly well documented and offers a stunning plunge into the workings of celebrity: it allows us to follow the destiny of a writer who was not really ready to become, from one day to the next, among the most celebrated men of his time for the next twenty years. Far from enjoying it, Rousseau felt this notoriety as a burden, a curse that condemned him to live “more alone in the middle of Paris than Robinson on his island, and sequestered from intercourse with men by the crowd itself, eager to surround him in order to prevent him from allying with anyone.”1 How is such a paradox to be understood?

“The Celebrity of Misfortune”

Like many after him, Rousseau had the experience of being a sudden celebrity, an event that threw him brutally onto the public stage. Beginning in the 1750s, before the success of his Discourse on the Arts and Sciences, he was only one of a number of writers trying to break into the Parisian literary world. At nearly forty years old, ten years after his arrival in the capital, he had only one piece of writing to show, Dissertation on Modern Music, which had had almost no success, and an opera, Les Muses galantes, that had not yet been performed. His system of musical notation, on which he had based all his hopes, was not accepted by the Academy of Sciences, while his talent for composition angered Rameau and raised suspicions, which closed the doors of the court and of patronage to him. Even his experience as embassy secretary in Venice, in 1743–4, ended with a stunning failure. He was lucky to obtain employment as secretary through Mme Dupin, the wife of a Farmer-General, and had gained the confidence of her son-in-law, Dupin de Francueil, the tax collector. Another glimmer of hope was his friend Diderot, who assigned him some articles about music for a vague encyclopedia project. All in all, his path resembled the banal one of a provincial autodidact who had come to Paris in the hope of succeeding but whose reputation had not made it beyond the narrow confines of the literary underground.

Everything changed in 1751 with the impact of the Discourse on the Arts and Sciences, which won the Académie de Dijon prize. Starting in December 1750, Abbé Raynal published the best sections in the Mercure de France, then the entire text in January 1751, which caused lively controversy. The text was an immediate sensation, far above the usual success of an academic dissertation.2 Diderot wrote him that no “example of such a success” existed. Several attempts at a refutation, including that of the former king of Poland, Stanisław Leszczyński, fed general curiosity and gave Rousseau a chance to refine his positions. He soon became a noted writer. Mme de Graffigny, herself a successful novelist, was overjoyed to meet him: “Yesterday, I met this Rousseau who is becoming so very famous for his controversial opinions and his response to your king.”3 A few months later, the Journal de Trévoux invoked the “splash” that his dissertation had made, even across borders. Antoine Court, at that time a theology student in Geneva, attempted to follow “the crush of writings” that appeared in opposition to the Discourse.4

From that moment on, Rousseau would never stop making cultural news. The following year, he continued to publish responses to his critics, had a play, Narcisse, performed, then, in spite of its failure, published it with the addition of a very long preface – forty pages – in which he wrote a self-justification which had an unexpected benefit: again it set off the interest he had aroused earlier. His opera Le Devin du village was a triumph at its Fontainebleau performance a few months later. Rousseau fed this incipient celebrity through a series of polemics against French music, against the theater, and then against his old friends the encyclopédistes. Finally, at the start of the 1760s, with the unprecedented success of La Nouvelle Héloïse, a publishing phenomenon, and the scandal provoked by the publication of Émile and the Social Contract, along with his condemnation in 1762 by the Paris parliament, his notoriety reached a zenith.

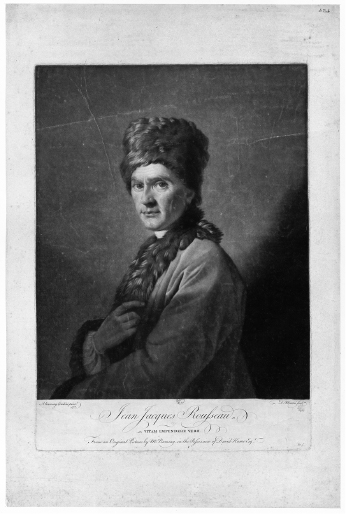

Threatened with arrest, Rousseau had to flee France immediately. This began a period marked by successive exiles which earned him the “celebrity of misfortune,”5 an expression he liked. He became both a successful writer and a public person, his life reported in detail in all the gazettes, his portrait reproduced in every form and avidly sought after by numerous admirers. In the mid-1760s, Rousseau was undoubtedly, along with Voltaire, the most renowned writer of his time. The European press reported the tiniest details of his life. In England, where his writings were translated and commented on, newspapers like the Critical Review, the Monthly Review, and also the London Chronicle or the St James's Chronicle often gave readers news of him.6 In 1765, given that the situation in Geneva had made him not only a literary celebrity but also a political one, there were articles about Rousseau every week.7 When young people threw stones at his house in Môtiers, the London Chronicle reported, with special emphasis, that the “celebrated John James Rousseau just missed being assassinated by three men.”8 A few months later, with his arrival on English soil, the author of Émile aroused a real media frenzy, even more because the English press saw him as a victim of the political and religious intolerance which held sway on the Continent. But it was above all the singularity of his rise to stardom and his personality which caused all the curiosity. “All the world are eager to see this man, who by his singularity, has drawn himself into much difficulty; he appears abroad but seldom, and dresses like an Armenian,” announced the Public Advertiser.9 As for David Hume who had persuaded him to come to London and who had not yet cut off ties with him, he did not know whether to be surprised or amazed by the spin that the British press give the tiniest details about Rousseau: “Every circumstance, the most minute that concerns him, is put in the newspapers.”10 When Rousseau lost his dog, Sultan, the news was announced the next day. When he found it, a new article appeared!11 When he arrived in London in January 1766, Rousseau went to the theater to see Garrick perform, but he was the one who was the veritable attraction that evening. All the newspapers recounted the event, describing the crowd that pushed to get a glimpse of him, emphasizing the curiosity aroused by his presence, and even more so because he was in his Armenian costume and sitting in the first row of the balcony, where he reacted in a very animated and dramatic way.

In February, the London Chronicle published a long biography of Rousseau that emphasized his immoderate taste for publicity. Rousseau, not surprisingly, was one of the most cited people in the Mémoires secrets, appearing more than one hundred and eighty-five times. Of course his writings were announced and commented on, but it was essentially the daily exploits of his life which fed the curiosity and interest of readers. The Mémoires secrets, and its readers, seemed fascinated by the persecutions which assailed Rousseau, by the quarrels which put him in opposition to authorities and his former friends, but above all the endless questions about his character.12 When he took refuge on Île Saint-Pierre, the Mémoires secrets affirmed that “The persecutions he has experienced have darkened his imagination, and he has become wilder than ever.”13 When he returned to Paris in 1770, his appearances were regularly reported in the Mémoires; as soon as he first appeared in the Café de la Régence, they were surprised at the “publicity surrounding the author of Émile,” in spite of the order for his arrest that in theory still threatened his liberty:

J.-J. Rousseau, tired of his obscurity and no longer being in the public eye, came to the city a few days ago and went to the Café de la Régence, where he was soon surrounded by a considerable crowd. Our cynical philosophe accepted this little triumph with great modesty. He did not seem alarmed by all the spectators, and his conversation was amicable, unlike his usual behavior.14

Rousseau's return to Paris was quite an event.15 His first appearances drew a crowd of gawkers eager to see the celebrated man. In the Correspondance littéraire, Grimm ironically described this fascination:

He showed up several times at the Café de la Régence in the Palais-Royal, his presence drawing a prodigious crowd, and the populace even gathered around the Place in order to see him pass by. We asked half of the people what they were doing there; they answered that they had come to “to see Jean-Jacques.” We asked them who Jean-Jacques was, and they answered that they had no idea, but he was passing by.16

“Jean-Jacques” had become an empty word, the rallying cry which announced an odd spectacle, a word the crowd repeated, a publicity slogan disconnected not only from the work of Rousseau, but even from his person. His celebrity was transformed into a pure tautological phenomenon, self-sustaining, where there only existed the excitement of the “populace,” the least enlightened and the least critical, at the idea of seeing a famous man, no matter who it was. Mme du Deffand made ironic comments herself about the “spectacle” that Rousseau made, worthy of street theater, and used the same pejorative term of “populace” to expand the derision to include all those who admired the writer, many from polite society: “Jean-Jacques is here. […] The show that this man puts on is at the level of Nicolet. It is really only the quick-witted among the populace who pay any attention.”17 Rousseau, however, soon ceased going to cafés at the request of the authorities, who reminded him that his presence in the capital was only just tolerated.18

In this last period, Rousseau played to the hilt the role of a famous man who hid from view, who sought anonymity in the heart of the capital. “The name of Rousseau is famous throughout Europe, but his life in Paris is murky,” wrote Jean-Baptiste La Harpe to the Grand Duke of Russia.19 The untold numbers of visitors who wanted to meet him had to outwit and foil his suspicions. The Duc de Croÿ expressed a desire to meet this Rousseau, a writer as difficult to see as he was famous: “For some time, I had wanted to see the famous Jean-Jacques Rousseau, whom I had never seen and who, three years ago, had come back to retire near Paris. We knew that Jean-Jacques frequented a certain café: we rushed there to see him, but he no longer went there and it was, it seemed, very difficult to approach him.”20 After hoping to be presented to Rousseau by the Prince de Ligne, he finally decided to go alone to the writer's home, in rue Plâtrière, where he was received without any trouble and spent two hours discussing botany with him.

The public figure of Rousseau was cemented the moment he refused celebrity. He was not only famous, he was famous for not wanting to be famous. He no longer published, claimed he no longer read books, and was satisfied to live frugally copying music. He systematically refused curious visitors or admirers. Many of his visitors competed with each other in finding ways to meet him, some bringing him music to copy, others, like the Prince de Ligne, pretending that they did not recognize him in order to better allay his suspicions. A visit to see Rousseau thus became a veritable literary genre, a necessary phase in narrative accounts of journeys to Paris. Later, in contemporaries' memoirs, all the same issues were almost always mentioned: the simple, austere life of Rousseau, his refusal to talk about books, his mix of friendliness and misanthropy, the quiet presence of Thérèse Levasseur, and, finally, his conviction that he was being persecuted. In most of these narratives, written down a few years later, many after the death of Rousseau and the publication of the Confessions, it is difficult to know what is true and what is fiction.

Thus, when Mme de Genlis describes in her memoirs a meeting with Rousseau in the autumn of 1770, she first of all paints a comic scene in which she mistakes him for an actor playing a role, then she describes the beginning of a friendship and edifying conversations, followed by a sudden rupture, Rousseau accusing her of taking him to the theater to show him off to the public, to be seen with him. This image of a sensitive, good man but one who was unjustly suspicious, who had an almost pathological relationship to his celebrity, corresponds perfectly to the collective portrait that numerous witnesses painted of Rousseau in the last years of his life and one which he himself accommodatingly maintained. The essential lesson of such stories was that a meeting with Rousseau had become a necessary encounter for anyone writing their memoirs. Even the glazier Jacques Louis Ménétra, though living in another social world than that of Mme de Genlis, recounted his lucky encounter with Jean-Jacques, their walks together, and the crowds that the presence of Rousseau excited in a café, with curious passersby climbing up on the marble tables to catch a glimpse of the author of Émile, much to the great distress of the owner of the establishment.21 As for Alfieri, who did not wish to meet the “famous Rousseau” during his visit to Paris in 1771, he felt obliged to justify himself when he drafted his memoirs.22

In spite of the silence in which Rousseau enclosed himself, not publishing and going out little, his celebrity did not seem to diminish. In 1775, his comedy Pygmalion was performed at the Comédie-Française without his permission and with great success, due to the name of the author. The novelist Louis François Mettra was not fooled: “Pygmalion continues to be successful. I repeat, it is the name of Jean-Jacques that gives verve to this sketch, which is not very theatrical.”23 The least little incident concerning Rousseau was reported in the press, which is shown in one episode that he himself recounted at length in his Reveries, when he was knocked over by a dog running in front of a carriage in Ménilmontant. All the European newspapers reported the event as well as the worry that it caused. One read in the Gazette de Berne, for example:

Paris, Nov. 8: J.J. Rousseau was returning from Ménil le montant a few days ago, near Paris, when a big Danish dog running very fast in front of a carriage with six horses, caused him to take a very bad fall. […] This celebrated man was transported to his home and there is still doubt that he will survive it. Everyone in Paris is very concerned; people constantly go to his place or send someone to find out how he is doing.

The Courrier d'Avignon even announced his death by mistake, which gave Rousseau the doubtful privilege of reading his own obituary.24 When he actually died the following year, the lively rumors concerning the possible publication of his Confessions showed that his celebrity had not dried up. The following years saw the apotheosis of Jean-Jacques, his transformation into a great man, as pilgrimages to Ermenonville show, then the publication of his complete works, and, finally, his induction into the Panthéon in 1794. This history goes beyond his celebrity. It became the history of his posthumous glory, his literary, intellectual, and political fortune. It was already part of the Rousseau mythology.25

Rousseau's celebrity became an aspect of his identity while he was alive. It was normal to associate him with celebrity, although a new concept, either to mock his taste for publicity or, to the contrary, to complain about his destiny. Starting in 1754, a visit by Rousseau to Geneva raised intense curiosity. The account of Jean-Baptiste Tollot, an apothecary and a Genovese man of letters, shows clearly that the interest of the observer was in the phenomenon of celebrity even more than in Rousseau himself, the way a celebrated man was capable of fascinating the public and focusing attention on himself.

I will confine myself to telling the truth about a man of genius, indeed, whose works are famous but who likes obscurity and who, far from wanting to be renowned, would rather that such renown be silenced; in a word, I am talking about the celebrated Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who through his eccentric, paradoxical life, through his energetic style, through the audacity of his pen, has attracted the attention of the public, which sees him as a rare phenomenon meriting its curiosity. […] All of Geneva has seen him, as I have, and from the highest to the lowest, everyone rushes to contemplate the man from Paris who has made a great many enemies, and the hate and jealousy coming from them have only made him more well known. […] It is obvious, of course, that not all the curious are in Paris; everyone wants to see this star, who is sometimes eclipsed, sometimes covered by a cloud.26

If the star metaphor foreshadows the “stars” of the twentieth century, most of the elements that form the basis of Rousseau's celebrity in the following years are already present. The author focuses on the avid curiosity that this singular man aroused, his mania for paradox and his encouragement of controversy: the notoriety of his name induced a desire to see, to contemplate even, this celebrated man. However, this enthusiasm also engendered criticism, which had to do with the excesses of public curiosity, not with the writer himself. Far from being accused of willfully nourishing this fascination, Rousseau is credited with the contrary desire for anonymity.

Tollot was one of the first to describe in specific terms the celebrity of Rousseau, the crowds who pushed and shoved to see him when he walked by, admirers who wrote to him and came to visit while he tried in vain to preserve a quiet, obscure life. He was not the only one. Most of his friends and admirers talked endlessly about the troublesome nature of celebrity, which Rousseau himself fostered whenever it pleased him, as we shall see. So, when he complained to Mme de Chenonceaux about the annoying visits he received, she said: “It is the misfortune of celebrity and in my opinion it is not a small one.”27 During the same period, shocked by reading in the press about Rousseau's misfortunes, his friend Deleyre wrote to him: “When I think, my friend, of all the pain caused by your talent and your virtue, your celebrity makes me tremble. […] How indignant I am to think of all the annoyances you have been subjected to these last six months and which I did not know about until I read of them in the newspaper!”28 As for Bernois Niklaus Anton Kirchberger, he offered him asylum: “My dear and loving friend, come and take refuge in my house, where you can stay as long as you like, and I promise to protect you from your celebrity, at least from that which is tiresome.”29 The same idea appeared in the newspapers: “This famous man, tired of being talked about, seems to want to retire to the countryside and live there in obscurity.”30

What is the basis of such a strong and long-lasting celebrity? At first, particularly in the 1750s, the notoriety of Rousseau rested on his capacity to excite scandal and controversy through the clever use of ambiguous opinions and a consummate sense of intellectual guerrilla warfare. The success of the first Discourse rested in large part on the fact that Rousseau turned the most well-established idea of his time on its head, shared both by Enlightenment philosophers and by most of their enemies, that of the link between progress in the arts and lifestyle. His discourse intrigued and invited refutation. “Isn't this simply a paradox with which he wanted to amuse the public?” asked Stanisław Leszczyński, one of Rousseau's first opponents. Intellectual polemics were followed by quarrels and noisy ruptures with his former friends, d'Alembert and Diderot, as well as a long-distance confrontation with Voltaire.

The romantic image of Rousseau as a solitary walker meditating on the meanness of his contemporaries has overshadowed his talent, although undeniable, as a polemicist. In 1752, he made up for the failure of Narcisse by publishing a provocative and rather arrogant preface in which he affirmed: “Here I am not writing about my play but about me. I must, in spite of my repugnance, speak about myself,” and he took advantage of the occasion to respond to all his critics. Just when all the debates aroused by his Discourse seemed to be exhausted, he started them going again by reaffirming his positions and by attacking his adversaries with new energy, reproaching scholars for defending science as a way to assure their authority the same way ancient pagan priests defended religion.

The following year, his Letter on French Music provoked a scandal. Rousseau was not content to simply defend Italian opera; he unleashed an all-out attack on French music, the violence of which surprised people.31 Thus it was hardly surprising to read in the Correspondance littéraire a few weeks later that he “had just set fire to the four corners of Paris.” “Never,” it added, “has one seen a quarrel louder or more intense.”32 The scandal was, indeed, so intense that musicians from the Opera decided to burn Rousseau in effigy. For a writer almost unknown two years before, this was already proof of his remarkable visibility.

Repercussions from the Letter on French Music did not only result from the aesthetic positions defended by Rousseau, but above all from the patriotic scandal aroused by his total rejection of French music. This episode reinforced the image of the paradoxical man which now accompanied him everywhere. How could an author who had just enjoyed such success with Le Devin du village, a French opera whose refrains were on everyone's lips, categorically condemn French music? This astonishment also came from the fact that Rousseau seemed to escape every possible category found in the intellectual field, an impression reinforced by the publication of the Discourse on the Origin and Basis of Inequality in 1755, then by his brutal rupture in 1757 with the encyclopédistes. Radical positions, a sense of provocation and polemic, even a taste for scandal, these elements constituted an explosive combination which could only incite the curiosity of the public. In the 1750s, Rousseau seemed in many ways to be a master of self-promotion.

In 1762, when Émile appeared, Rousseau was still this paradoxical author figure putting his eloquence to work writing provocative theses, which the Mémoires secrets invoked in order to explain the expectations raised by the book: “This work, announced & awaited, piques the curiosity of the public because the author combines great genius with a rare talent for writing with as much grace as energy. He is reproached for sustaining paradoxes; in part this has to do with the seductive art he uses and to which perhaps he owes his great celebrity; it is only since he took this path that he has been distinctively singled out.”33

Ami Jean-Jacques

At this point, however, the celebrity of Rousseau was enriched by another dimension: to the curiosity aroused by the eloquent writer, never short of paradoxes, was added a sentimental aspect found in La Nouvelle Héloïse. The novel's success, published early in 1761, was prodigious. In spite of its often lukewarm, even disdainful, reception by writers and critics, the book was adored by the public. “Never has a work created such an astonishing sensation,” noted Louis Sébastien Mercier, describing the public's fascination. The first editions were immediately sold out and bookstores loaned the book page by page to readers. Even those who did not read the book could not escape the collective enthusiasm. The young Princess Czartoryska, sixteen years old and visiting Paris, got caught up in the latest fashion and ordered miniatures inspired by the book: “I don't read anything and I have never read anything by Rousseau, but they talk endlessly about La Nouvelle Héloïse and every woman wants to be like Julie. I thought I had better join the ranks.” Having managed to obtain a visit with Rousseau at his house, she showed up “with the eagerness one has to see something new, to see a show.”34

Many people, however, had read the novel and received a real emotional shock. “From the first pages, I was delirious. […] Days were not long enough, I read at night, and had one emotional upheaval after another. I reached the last letter from Saint-Preux, no longer crying but screaming, howling like an animal,” General Thiébault remembered in his Mémoires.35 The publication of La Nouvelle Héloïse marked a date in the history of reading, as many readers testified by writing to Rousseau and telling him about their emotions. From that time on, Rousseau seemed to be the master of feelings, a man who spoke the language of virtue and whose works had the power to make his readers better by pulling tears out of them. The young Charles Joseph Panckoucke, at that time a publisher in Rouen, did not hesitate to write Rousseau a passionate letter:

Your divine writings, Monsieur, are a fire which devour, they have pierced my soul, strengthened my heart, enlightened my mind. Having for a long time been given over to the treacherous illusions of impetuous youth, my reason had gone astray in the search for truth. […] A god was needed, a powerful god, to pull me back from the precipice and you are, Monsieur, the god who has worked this miracle. […] Your tender and virtuous Héloïse will always be for me the code for moral sanity, the source of all my ecstasy, all my love and all my desires, and you, Monsieur, will have my most profound veneration and respect. I adore you and your sublime writings, all those lucky enough to read your work will find in you a trusted guide who will lead them to perfection and to love and to the practice of all those virtues that make up the essence of a good man.36

Behind the bombast, very characteristic of the sentimental style of the period, one can perceive the moral and spiritual experience that La Nouvelle Héloïse represented for many readers. Up until that moment, Rousseau had been a censor, denouncing the vices of modern society. He now became a guide, opening up for his readers a path to moral regeneration and happiness. The letter also revealed the transfer of feeling to the author, which authorized, even stimulated, the writing. The bond was no longer simply curiosity or admiration, it was primarily an outpouring of gratitude, of “eternal acknowledgment,” which invited effusion and led the reader, when he began writing, to imitate the hyperbolic style of the novel, sentimental and moral, where tears and pity led to virtue.

It is likely that Panckoucke, a young publisher from the provinces, was not totally disinterested in showing his admiration for a successful writer. But such an effusion went beyond professional flattery and Rousseau received several hundred similar letters in the months following the novel's publication. These letters were so numerous, several hundred in just a few months, that Rousseau talked about a “multitude” and even thought about publishing them.37 Sadly, not all the letters were saved, but those we have demonstrate this same sentimental enthusiasm for the work and for the author. Most notable of all are the large number of ordinary readers, sometimes anonymous. One of them thanked Rousseau for “the only good moments” he had had in the last six years. He found in the novel echoes of his own situation and his impossible love: “I was so carried away that if the immensity of the oceans did not separate me from you as from my Julie, I would not be able to stop myself from giving you a huge hug and thanking you a thousand times with the delicious tears that you pulled out of me. Perhaps one day I will be impelled to meet you, and I will certainly find a way.”38

Some readers, it is true, kept a calmer tone, even a critical one. Thus, Pierre de La Roche, a man from Geneva who was living in London, wrote long letters in which he discussed the work point by point. But even this gesture, although without passionate feeling, was only possible because Rousseau was not simply an author, but a public figure one could talk to. Most of the time, readers wrote to thank him and above all to talk about the change the book had produced in their lives. Jean-Louis Le Cointe, a Protestant from Nîmes, owed Rousseau for his discovery of the “charms of virtue.” When he wrote to Rousseau, he hesitated between the distance which separated him from a great writer and the affective proximity allowed by the novel: “I feel all my temerity and I condemn it; but the more you inspire me with respect, the less my heart can refuse the pleasure of telling you about the feelings you have caused to be born in me.” Then he opened up even more to the person who had given him the means to understand his life differently. “Being sincerely attached to a young wife, you have made it known to the two of us that what seemed a simple attachment through the habit of living together is the most tender love. Father at age twenty-eight of four children, I will follow your lessons in order to make men of them.”39

Not all readers wrote directly to Rousseau, certainly not when they discovered the novel several years after its publication. Manon Phlipon, who would play an important political role during the Revolution under the name of Mme Roland, was only seven years old when La Nouvelle Héloïse appeared, but, in the 1770s, she was enthusiastic about the author, whose books she devoured and whom she dreamed of meeting. “I'm angry that you do not like Rousseau, because I like him more than I can say,” she wrote to her best friend. “Just talking about this excellent Jean-Jacques my soul is moved, animated, warmed: my taste for study is reborn, for the true and the beautiful of every kind.” Openly proselytizing, she insisted on sharing her fascination: “I am so astounded that you are amazed by my enthusiasm for Rousseau: I regard him as a friend of humanity, its benefactor and mine”; and: “I know that I owe to his writings what is best in me. His genius has warmed my soul: I feel it wrapping me in flames, lifting me up and ennobling me.”40

The enthusiasm created by the reading of Rousseau's books, La Nouvelle Héloïse and Émile above all, translated into an attachment to his person. This was reinforced by Rousseau's misfortunes, by the stories in the press of his bad luck and his successive exiles. It obviously opened up the theme of a persecuted Rousseau, constrained to live in retirement and in solitude:

The persecutions, the injustices by men, almost gave Rousseau the right not to believe in their sincerity. Tormented in every country, betrayed by those he thought were friends in a manner even more painful because his sensitive soul saw their evil ways without being able to delicately unmask them; persecuted by his ungrateful country, which he had exemplified, enlightened, served; exposed to the traits of envy and meanness, is it any wonder that retirement seemed to him the only desirable asylum.

Rousseau's fans easily went from admiration for his writing to an unconditional defense of the man.

In a seminal essay, Robert Darnton highlighted one of Rousseau's readers, Jean Ranson, a merchant from La Rochelle who kept up a regular correspondence with the director of the typographical company in Neuchâtel. He ordered books, but also took the opportunity to ask after his “Ami Jean-Jacques.” Although he had never met him, Ranson saw in Rousseau a familiar person, a friend of the family to whom he was bound by a long-distance intimacy, thanks to the reading of his books, but also thanks to the news about him found in journals and in his letters. Darnton clearly showed that this attitude was related to a new practice of reading adapted to the Rousseauistic language-of-the-heart rhetoric. Because readers found in the novel, or in other writings by Rousseau, elements that seemed to describe their own lives and clarified their subjectivity, they in turn went further than the text, which was only a pretext for directing their admiration and affection toward the author. “The impact of Rousseauism therefore owed a great deal to Rousseau. He spoke to the most intimate experiences of his readers and encouraged them to see through to the Jean-Jacques behind the texts.”41 This affective reading was so successful it logically led the reader to entertain a mesmerizing relationship with the person of the author. However, determined to create a history of reading based on an ethnographical approach to the culture of the Ancien Régime and a “mental world that is almost unthinkable today,” Darnton depicted the affective link forged between Rousseau and his readers as the expression of a mysterious attitude, favorable to sentimental effusiveness, that would seem strange to us now: “The Rousseauistic readers of prerevolutionary France threw themselves into texts with a passion that we can barely imagine, that is as alien to us as the lust for plunder among the Norsemen or the fear of demons among the Balinese.”42 But is this enthusiastic attachment so completely strange to us today when crowds stood in line for hours at the appearance of a new volume of Harry Potter, or vast numbers of inconsolable fans grouped together to weep at the death of Princess Diana or Michael Jackson?

Reader reactions to Rousseau's work were not so “naïve,” nor so exotic. Far from believing that Julie and Saint-Preux really existed, as one often thought, most had fun with the ambiguity upheld by Rousseau concerning the authenticity of the letters, according to a procedure which was already, at that time, a hackneyed commonplace. A number of readers enjoyed, as readers would do today, imagining keys to an autobiographical reading, persuaded that Rousseau was inspired by his own amorous dalliances in order to imagine the fate of his characters and give them such eloquence. Consequently, interest in and pity for the characters transferred to Rousseau, who had been capable of creating them and who could not have done so, they thought, unless he had himself lived through comparable ordeals. The main principle of the romance novel, to move readers emotionally and to give to virtue a romance form through a process of identification with the moral dilemmas of the characters, strongly encouraged such an affective transfer to the author.43

The enthusiasm expressed by Rousseau's correspondents, their desire to weave an intimate bond with him, both friendly and spiritual, in spite of distance, were not the traits of an old and irrational attitude, but rather the joint effects of a work that lauded romantic effusiveness and of new forms of literary communication. The religious vocabulary, very present in Panckoucke, that of moral and spiritual conversion employed by so many readers, should not be construed as an error. This was not a matter of a “cult” or a quasi-mystical surrender, but a new formulation of the bond that individuals who made up a public had with a contemporary celebrity, one with whom they identified or whom they had chosen as a guide and virtual friend. This relationship, a truly intense one, had strong affective or moral dimensions, especially when the famous person, as was the case with Rousseau, offered through his work or the example of his life means to a “recovery of oneself.”44

The relationship that numerous readers wove with Rousseau, through his books, came from this friendly imagined intimacy. This is what clearly appears in the Jean Ranson correspondence. This was not a young reader, passionate and fanatical; he was a rational merchant but one who found in “l'Ami Jean-Jacques” sound moral principles. “Everything that l'Ami Jean-Jacques has written about the duties of husbands and wives, of mothers and fathers, has had a profound effect upon me, and I confess to you that it will serve me as a rule in any of those estates that I should occupy.” This does not arise from an improbable identification, nor from a religion, nor from confusion between fiction and reality. Ranson forged a long-distance friendship with Rousseau, both real and imagined, which served him as a guide. It was under this form of amicable intimacy that he took a “lively interest” in the person of Jean-Jacques, demanding on several different occasions of Jean-Frédéric Ostervald news about “his friend Jean-Jacques's” health. When Rousseau died, Ranson cried out: “So, Monsieur, we have lost the sublime Jean-Jacques. How it pains me never to have seen nor heard him […] Tell me, I pray, what you think of this famous man, whose fate hs always aroused the most tender feelings in me, while Voltaire often provoked my indignation.”45

It is clearly this conjunction of Rousseau's celebrity, the emotional and moral power of his books, and the sympathy toward his misfortunes which pushed people to react: readers wrote to this celebrated man, without knowing him, to testify about their feelings and the desire they had to meet him. No one expressed this aspiration more strongly, perhaps, than a nobleman from the south of France who affirmed that his soul felt “the strongest passion” for Jean-Jacques and he would now write to him each week until Rousseau decided to respond to him. “If Rousseau did not exist, I would need nothing. He exists, and I feel that something is missing in me.”46 As for the clock-maker Jean Romilly, he ruminated for several months over his letter and admitted openly the place that Rousseau, as an imaginary friend, had in his daily life, to the point of becoming an obsession:

I can no longer defer talking with you, it is almost two years now even three that I have wanted to tell you about all the idealized conversations I have with you because you should know that whether I'm sleeping or walking about, you are always present in my mind and I am only at ease in company when I can talk a little about you, either to those who love you or those who do not love you at all.47

The correspondence that Rousseau and Mme de La Tour maintained for ten years shows how the bond starts, sentimental and playful, asymmetric and fragile, between the author and one of his admirers. This admirer, a member of the gentry, separated from her husband and thirty years old when La Nouvelle Héloïse appeared, did not start a correspondence with Rousseau on her own initiative. It was her friend, Mme Bernardoni, who began a correspondence with him, half-flirtatious, half-serious, assuring him that she knew another Julie possessing all the merits of the book's heroine. Taking the role of Claire, she got Rousseau to answer the letters. Thus began a game among them where Mme Bernardoni, who would quickly disappear, played the role of mischievous go-between with her devoted friend Mme de La Tour as the obliging admirer, with both of whom Rousseau, at first, did not mind multiplying allusions to the novel and to the trio that they could, themselves, create. Then developed a long-standing correspondence between Rousseau and Mme de La Tour, which lasted until a rather sudden rupture was imposed by Rousseau ten years later. Mme de La Tour was demanding, endlessly restarting the correspondence over and over again, tirelessly asking news from Rousseau, showing her interest and her worry, reading and rereading his works (“My friend, I must tell you about my enchantment: I am reading La Nouvelle Héloïse for the seventh or eighth time: it moves me more than the first time I read it!”),48 always multiplying enthusiastic commentaries and indiscreet questions. Rousseau moved from an amicable tone, even tender (“Dear Marianne, you are hurt, and I am disarmed. I feel nothing but tenderness when I think of your beautiful eyes in tears”),49 to much more distant phrases, even long suspicious silences; but all in all, he wrote more than sixty letters to her, turning these long, improvised gallantries into an epistolary friendship.50

It was not enough for Mme de La Tour to read and reread the works of Rousseau, dreaming about the loves of Julie and Saint-Preux, and writing to her “dear Jean-Jacques” long letters in which she deplored the fact that he did not answer more assiduously. Her zeal pushed her to take his side when he was attacked. Thus, at the highest point of the quarrel with David Hume, in 1766–7, she published a libelous, anonymous piece meant to justify Rousseau, and then she drafted a second one. When Rousseau died, she took up the pen again to defend his memory, with a series of letters addressed to Élie Fréron's L'Année littéraire, in the form of a volume entitled Jean-Jacques Rousseau vangé [sic] par son amie (Jean-Jacques Rousseau Defended by His Friend).51 Mme de La Tour was not the first to go from private admiration to public apology. Panckoucke, whose emotions we saw when La Nouvelle Héloïse appeared, took up the pen a few weeks later to reply in the Journal encyclopédique to jokes made by Voltaire.

What is revealed here is the complexity of the reactions aroused by the celebrity of Rousseau, not only a successful author whose paradoxes were intriguing, but also the “champion of sensitive souls,” the author of a great romance novel that certain readers read over and over again, a persecuted writer, forced to flee France, then Geneva, then Switzerland, in search of refuge. Beyond the curiosity fed by the chronicle of his misfortunes and his eccentricities, causing crowds of curiosity seekers to gather wherever he went, there existed a more profound attachment between “Jean-Jacques” and his readers, woven from empathy and a desire for intimacy, from admiration and gratefulness. For readers like Ranson, Panckoucke, Manon Phlipon, or Mme de La Tour, just a few examples among many known and unknown, Rousseau was not only a fashionable person, he was an imaginary friend they were always ready to empathize with and defend. The characteristic paradox of celebrity, and more generally mass culture, was that Rousseau's readers lived their bond with “l'Ami Jean-Jacques” in a particularly personal and singular way, even though the bond was perceived identically by numerous other readers.

The public reaction to the heated quarrel between Rousseau and David Hume in 1766 demonstrates this attachment to the celebrated man. Hume had agreed to the demand of two of Rousseau's friends and protectors in polite Parisian society, Mme de Luxembourg and Mme de Boufflers, to find him asylum in England at the height of the persecution exercised against him in France and in Switzerland. Sadly, the relations between the two men worsened very quickly. Rousseau, convinced that Hume was in league with his enemies, refused the pension offered by George III that Hume had been able to obtain, writing Hume a shocking letter full of insane reproaches. Sickened and worried, Hume hurriedly wrote to Holbach and d'Alembert to show them the tenor of the letter and ask their advice. The move was maladroit and had dreadful consequences. The quarrel between the two men resounded everywhere, first in the closed circles of Parisian salons, where Rousseau's enemies were overjoyed, then in the press. A private dispute between two men became a literary event, a veritable public quarrel, the effects of which were felt by Rousseau for a very long time, alienating him from the support of his powerful protectors.

I have described elsewhere the mechanisms and the social stakes at issue in this quarrel.52 But the public dynamic must be emphasized here, the reactions of anonymous readers who wrote in defense of Rousseau. Hume himself was stunned: “I little imagined, that a private story, told to a private gentleman, could run over a whole kingdom in a moment; if the King of England had declared war against the King of France, it could not have more suddenly been the subject of conversation.”53 Hume's strategy and that of his Parisian friends was to keep the grievances against Rousseau private, in order to avoid engaging in a public polemic that might have destroyed Hume's image, a most hazardous outcome. They hoped to keep the situation within the world of the salons and the closed circles of polite society, that area where reputations were made and lost. There, thanks to an intense campaign to denigrate Rousseau, emphasizing the spotless renown of the “good David,” who had been, during his visit to Paris, the darling of polite society, it was a matter of definitively destroying the reputation of Rousseau in the minds of Mme de Luxembourg, Mme de Boufflers, and his other patrons. Moreover, the mission appeared easy because Rousseau had opted to keep silent, not responding to those who asked him for explanations, unless he just told them to mind their own business.

Hume's friends made one mistake: they underestimated the celebrity of Rousseau. He was not only a player in the little literary world of the capital, he was also a public figure. In just a few days, extracts of the letter from Hume to Holbach were widely circulated, much beyond society circles, feeding “public rumors.” Less than a month later, the newspapers seized on the affair, first with an article in Le Courrier d'Avignon, then in the English papers. The St James's Chronicle, for instance, published a series of articles about the quarrel over the course of the summer and into the autumn of 1766.54 Confronted with the sudden publicity given his rupture with Rousseau, Hume was forced to change strategies. Convinced he was right and in order to put an end to the rumors, he asked his friends to publish articles, including the long accusing letter written by Rousseau, accompanied by Hume's own commentary. However, contrary to his intentions, far from ending the affair by proving the ingratitude and madness of Rousseau, this started the controversy all over again and engendered numerous reactions. Mme de La Tour, as we saw, took up her pen to defend Jean-Jacques. But her text only strengthened the Justification de Jean-Jacques Rousseau, the author of which was anonymous. In the form of pamphlets and letters from readers, there were numerous admirers of Rousseau who took up his defense.

Rousseau's letter to Hume, which the latter thought was a madness, was read conversely by many readers as proof of the author's innocence: unhappy, sincere, and persecuted. The effectiveness of this text was due to the fact that it was drafted in the romantic and hyperbolic style of La Nouvelle Héloïse, certain passages even using the same sentences employed by Saint-Preux.55 The identification of Jean-Jacques with Saint-Preux, which had already been used successfully in the 1761 novel, worked again five years later. The conflation was almost total between the individual Jean-Jacques Rousseau, the author of La Nouvelle Héloïse and Émile, and the public figure “Jean-Jacques,” constituting a series of collective representations, certain of which were driven by the press, others kept alive by his writings.

The relative isolation of Rousseau in the Paris literary world, and even his silence, his refusal to respond and to defend himself, worked in his favor because it seemed, for his public, to testify to his sincerity. In the eyes of his admirers, Rousseau was not an author like others, fighting for his reputation, but a reasonable man who was suffering. “I do not live in the world, I do not know what is going on there; I have no reference points, no associates, no intrigues,” he wrote to Hume on July 10.56 On the other hand, he had many readers for whom he was “l'Ami Jean-Jacques.” The anonymous author of the Justification de Jean-Jacques Rousseau dans la contestation qui lui est survenue avec M. Hume claims to have seen in Rousseau's letters to Hume “only the traces of a beautiful soul, generous, delicate and too sensitive, just as Rousseau has shown us in his writings and even more by his behavior.”57 After having claimed that he did not know Rousseau personally, he concluded:

Who would not admit that Rousseau was forced to conduct himself the way he did in regard to M. Hume, and that on this occasion he showed his soul to be beautiful, delicate, and sensitive, an intrepid soul above adversity? Ah! Who is the virtuous man who could be distanced from the society of Rousseau by this event? And who, to the contrary, would not desire to become the friend of a man so full of candor, so worthy of esteem.58

In the same vein, the similarly anonymous author of the Observations sur l'exposé succinct de la contestation qui s'est élevée entre M. Hume et M. Rousseau, in an eighty-eight-page brochure, dissects almost word for word reproaches addressed by Hume to Rousseau and makes a judgment about this quarrel between “two celebrated men” almost entirely in favor of the latter. The thesis he defends is that of a conspiracy plotted by Rousseau's enemies, in Geneva and in Paris, of which Hume was the more or less conscious agent. While claiming twice that he did not know Rousseau “except by his work,” he claims to be among his “friends.” These various pamphlets answer for Rousseau and are a comfort. The author of these observations comments:

As I finish these observations, a pamphlet is being published [it is the Justification de Jean-Jacques. Rousseau] which brings honor to the heart of the person who wrote it: it is wrong in supposing that the friends of M. Rousseau have been beaten: the ones I know are tireless; certain of the probity and sincerity of their friend, they imitate his silence: my decision to break this silence rests on the notion that virtuous men will always recognize each other, and someone who is unknown cannot be accused of bias.

The defenders of Rousseau constituted a sort of elective community, not a claque like the one around Hume, accused of working together secretly to destroy Jean-Jacques, but a group of the writer's friends who often did not know him except through his work but were convinced of his innocence, his sincerity, and the persecutions that hounded him. They made of their anonymity an argument for impartiality and perceived their public commitment in his favor as an act of justice that they would tirelessly uphold.

Hume and his friends, and some historians after them, were surprised by the public support Rousseau received and the turn the quarrel took.59 Although they had intended to discreetly destroy the reputation of Rousseau in literary and social circles, they found themselves instead mixed up in a public quarrel that left Hume with a bitter taste. Although there was no doubt in their minds that Rousseau was wrong on all counts regarding the norms of polite society – he had virulently attacked, without proof, a man who was his patron – a large part of the public judged the affair differently. Hume's strategy, along with Holbach and d'Alembert, was based on a series of social conventions (politesse, patronage, etc.) which guaranteed the control of reputations through conversation and within inner circles. The public was held in suspicion. Holbach, as prudent in the salons as he was radical in his writings, wrote to Hume that “the public thinks very badly of quarrels that demand a judgment from it,” while d'Alembert warned him: “It is always disagreeable and often a nuisance to be tried by written word before this stupid animal called the public, which asks nothing better than to speak badly of those whose merit offends it.”60 What matters, Holbach resumes, is to retain “the esteem of enlightened and impartial persons, the only people a gallant man desires the approval of.”61 But this strategy ran up against another principle, a new one, that of celebrity, which immediately nullified their attempt to keep the affair quiet and provided Rousseau with anonymous, albeit widespread, support.

One of the aspects of the quarrel, from the outset, was the pension that Hume had obtained for Rousseau from George III. Rousseau had refused all pensions the previous fifteen years because he wanted above all to be independent, and thus the royal pension bothered him. The affair was complicated; it seems that at first Rousseau accepted the pension on condition that it be accorded in secret; then he changed his mind. Whatever happened, he ended by believing that Hume had only made the request in order to put him in an impossible position, forcing him to contradict himself and be discredited. In the eyes of Rousseau, this was a grave situation that put into question his whole way of life. For Hume and for most of his contemporaries in polite society, this was only a pretext. Turgot assured him: “No one in the world could imagine that you asked for a pension for Rousseau in order to dishonor him. Only he would think that a pension was dishonorable.”62 Rousseau's readers, on the other hand, had another opinion: “Rousseau ungrateful! It's been proven that he is nothing of the sort. Rousseau is proud, perhaps. But a pride that is above money, which leads us to live off the fruit of our labors, which protects us from all cowardly compromises, is an estimable pride, and, unfortunately, far too rare among men of Letters!”63 the author of the Justification de Jean-Jacques Rousseau exclaimed again. What was at stake here was Rousseau's singular position in the literary world, his refusal of common norms, his wish to construct an atypical public persona. This attempt to create an exemplary public image was itself a powerful factor in his celebrity.

Eccentricity, Exemplarity, Celebrity

Detractors and flatterers of Rousseau were alike on one point: he did nothing the way others did. His public image was that of an absolutely unique and eccentric man. A mad man, said his enemies; a sensitive man without equal, responded his admirers. He, as we know, made of this singularity, at an existential level, the very heart of his Confessions: “I am not made like any of the [men] I have seen; I dare to believe that I am not made like any that exist. If I am worth no more, at least I am different.”64 But this originality is strongly projected into the public sphere through the persona of “Jean-Jacques.” Rousseau, however, was not content just to be different; he wanted to let it be known.

The element that contributed most to the construction of an eccentric public persona was the famous “personal reform” that Rousseau undertook at the beginning of his notoriety, after the publication of the Discourse on the Arts and Sciences. It consisted in making his lifestyle conform to his principles, and breaking with traditional forms of patronage and the lifestyle of writers in the Ancien Régime. Rousseau gave up his position as secretary to Dupin de Francueil, renounced habits of dress customary in polite society, refused presents and pensions, and chose to earn his living by copying music. He thus manifested, both publicly and in his own eyes, his independence in regard to the elites.65

Before evaluating the consequences of this principle, one needs to take it seriously. The insistence on an exemplary life fulfills several functions. For one, it assures Rousseau of his own authenticity. This decision is part of a long intellectual and moral tradition which goes back to ancient philosophy and was revived in the Renaissance, during which philosophy was not simply a question of doctrine, but also an ethical question, a way of life, a self-exploration to find a more authentic, a truer way of existence.66 Rousseau says it again in the Reveries of the Solitary Walker: “I have seen many who philosophized much more learnedly than I, but their philosophy was, so to speak, foreign to them.”67 Opposed to philosophy as simply knowledge about the world, an intellectual exercise, Rousseau defended a concept of thought which was much more personal, first of all an exercise in self-knowledge and a means to perfectionism. On the other hand, while publicizing this philosophical and moral exemplarity, Rousseau also meant to guarantee the credibility of his philosophical discourse, and in particular the biting criticism that he addressed to his contemporaries. As he always said, an authentic thinker is the one who is ready to sacrifice everything for the truth. According to a suggested formulation: “If Socrates had died in his bed, people today might suspect that he was nothing more than a clever Sophist.”68 Returning to the Confessions concerning this double conversion, at once theoretical and biographical, which marked his sensational entrance into the world of letters, Rousseau wrote: “Moreover, how could the severe principles I had just adopted be harmonized with a station which had so little relationship to them, and would not I, a Cashier of a Receiver General of finances, be preaching disinterestedness and poverty in good grace?”69 This formulation draws attention because of its ambiguity: Is it meant to save the credibility of his principles by avoiding ridicule? This ambiguity is at the heart of Rousseau's choices, always worried about the public effect that would be produced, even as he openly fretted about the theoretical and ethical logic of an idea. One can opt for either a comprehensible or a critical reading of these choices. In the first case, one judges that the claims of exemplarity by Rousseau necessarily have two sides. In relationship to oneself, an ethical concern, it is fundamentally a private affair. In terms of a pedagogical argument, meant to balance his works by giving them extra weight, it is necessarily public. In the second case, a less charitable reading might be that this concern about exemplarity was, first of all, a concern about attracting public attention. The result is the same: the claim of authenticity and consistency is not only a personal and intimate experience, a solitary investigation of self; it is, from the beginning, loudly proclaimed by Rousseau through indiscreet acts such as refusing a royal patronage following the success of Devin du village, or adopting an incongruous but practical piece of clothing, a kind of Arab kaftan that he called his “Armenian robe” and which was meant to show his disdain for conventions and inner circles, his choice of a simple life, without luxuries, close to nature. These clothes became a recognizable sign of the “Jean-Jacques” public persona, feeding in his enemies a suspicion of histrionics.70

Rousseau's worry about exemplarity illustrates perfectly the public dynamic for him: it was matter of pride to publicly take responsibility for his ideas, to sign all his books with his own name rather than hide behind pseudonyms or a clever anonymous usage. While Holbach, for example, published treatises on atheism under pseudonyms and managed to stay anonymous all his life, and Voltaire endlessly played the game of pseudonyms, even when they were transparent and only served to save face, Rousseau, for his part, refused to play even the most minimal game by pretending not to recognize his writings when they were published without authorization.71

When Rousseau voluntarily published the Social Contract and Émile, only four years after the scandal provoked by Helvétius's De l'Esprit and condemnation of the Encyclopédie, everyone saw in this a real political provocation. His refusal of anonymity, even the façade of it, particularly irritated the authorities and increased their severity. The decree from the Archbishop of Paris explicitly reproached Rousseau, and the same went for the parliamentary injunction against Émile on June 9, 1762: “That the author of this book, who has not feared to give his own name, should be prosecuted swiftly; that it is important, since he has made himself known, for justice to make an example of him.”72 The choice that Rousseau made to sign his works, to publicize his name, appeared to be a major part of the scandal. Voltaire himself did not understand why Rousseau refused to take the most minimal precautions and reproached him for putting the entire philosophical movement in danger. He notes in the margins of his copy of the Letter to Beaumont: “And why did you use your name? poor beggar [pauvre diable],”73 which, for Voltaire, meant a writer trying to live from his pen, “literary riff-raff,” as he sometimes said, opposed to the figure of a gentleman writer who knew how to elegantly stage his public appearances.

For Rousseau, on the other hand, the choice to sign his texts was a fundamental element in taking political responsibility as a writer.74 He explains this in his Letter to Beaumont, the Archbishop of Paris,75 and especially, and at length, in his Letters Written from the Mountain, a polemical text written in response to the public prosecutor Tronchin, in the troubled context of political conflicts in Geneva and following the condemnation of the Social Contract by the Geneva Advisory Council.76 Rousseau demanded to be judged in person and developed an argument in which a book signed could not be condemned in the same way an anonymous book could be. The condemnation of a book recognized by its author could not be made against a text alone; it had to necessarily include the intention of the author and implied a proper trial. The argumentation was laid out in two stages. Rousseau first of all delivered an ironic satire on the usual practice of anonymity, denouncing its hypocrisy:

Several are even in the practice of avowing these Books in order to do themselves honor with them, and of disavowing them in order to put themselves under cover; the same man will be or will not be the Author, in front of the same man depending whether they are at a hearing or at a supper. […] In that manner safety costs vanity nothing.77

Then he demanded to defend himself. Because he had signed and taken responsibility for his text, he insisted it was not possible to dissociate his writing from his person. It was not the text itself which was condemned, but the act of announcing it and the intention of the author.

But when a clumsy Author, that is to say, an Author who knows his duty, who wants to fulfill it, believes himself obliged to say nothing to the public without avowing it, without naming himself, without showing himself in order to respond, then equity, which ought not to punish the clumsiness of a man of honor as a crime, wants one to proceed with him in another manner. It wants one not to separate the trial of the Book from that of the man, since by putting his name on it he declares that he does not want them separated. It wants one not to judge the work, which cannot respond, until after having heard the Author who responds for it.78

This theory about the author's intellectual responsibility and criminal liability rested on the impossibility of distinguishing the book from the writer. But it is clear that a statement like this implies transforming the author into a public figure since, as soon as the book is published, he “is known and ready to answer for it.”

Here again, claiming responsibility is accompanied by a desire for recognition. In Letters Written from the Mountain, the vocabulary of honor is omnipresent. Rousseau strongly reproached the Advisory Council for having “destroyed his honor,” and for having “stigmatized [him] by the hand of the Hangman.”79 The entire text thematically works by contrasting the honorable man, who insists on signing the books he publishes (one could say he makes it a point of honor), and the infamy which touches him by the condemnation of his book: “When one burns a Book, what does the Hangman do? Does he dishonor the pages of the Book? Who ever heard it said that a Book had any honor?”80The honor associated with a work of literature sometimes expressed itself in the form of proud claims of authorship, as when Rousseau wrote to his printer Marc Michel Rey concerning the publication of the Letter to d'Alembert: “Not only can you name me; but my name will be there and it will even be in the title.”81 It is difficult not to see here a publicity strategy as well, one based on an acute awareness of the scandal that the book will provoke and the notoriety of its author.

This willingness to put his name on his books, when it was traditional to hide names, by prudence or out of respect for the values of the elite, was made clear by Rousseau in his preface to the second edition of La Nouvelle Héloïse:

| R. | Own it Monsieur? Does an honorable man hide when he addresses the Public? Does he dare to print what he would not dare acknowledge? I am the Editor of this book, and I shall name myself as Editor. |

| N. | You will name yourself? You? |

| R. | Myself. |

| N. | What! You will put your name on it? |

| R. | Yes, Monsieur. |

| N. | Your real name? Jean-Jacques Rousseau, in full? |

| R. | Jean-Jacques Rousseau in full.82 |

And indeed, the cover of the book carried the name of Rousseau starting with its first edition, a rare practice with novels. Behind his justification of sincerity and transparency, Rousseau burst with pride, even jubilation, at repeating and almost trumpeting his name; this authorial gesture showed an ostentatious break with standards of literary seemliness, provocation being part of the challenge. This attitude was logical given his refusal to imitate the aristocratic or fashionable figure of the writer. Writing was neither a job nor a hobby, but a vocation, even a mission, complete with social and public usefulness. This emphatic affirmation, often repeated by Rousseau,83 was here treated in a rather ironic way. It contributed to associating the name of Rousseau with his works. The attachment Rousseau had to his family name, his refusal of pseudonyms, was not only a principled stance; it was inseparable from an affirmation of self by way of a proud announcement of his identity, social, personal, and authorial, where the name was the mark of credibility. Even during those periods when he was threatened by the authorities, Rousseau generally refused to travel under an assumed name. He wrote to his friend Daniel Roguin, for example, who wanted to invite him to Yverdon after the condemnation of Émile, that “in regard to going incognito, I cannot bring myself to take someone's name, nor to change it. […] Therefore Rousseau I am, and Rousseau I want to remain, whatever the risk.”84

These different elements (the refusal of pensions and presents, avowed suspicion of the manners of polite society, the choice of unusual clothing, the declaration of his name) all went together: they created the Jean-Jacques persona, not only a talented polemicist or romance novelist, but also an eccentric person who did not seem to conform to any of the ways of the literary world at the time. This individuality nourished Rousseau's discourse in an obsessive way: Was he sincere and authentic, or was it only a pose, a way to attract public attention – a publicity gimmick, in other words? On this point, Grimm for once outdid Fréron. The latter denounced Rousseau, as early as 1754, for “his frantic need to be talked about in society”; the former described Rousseau, a few years later, as “this writer famous for his eloquence and his singularity,” and sarcastically added: “The role of eccentric always succeeds for those who have the courage and the patience to carry it off.”85

Others went even further, denouncing in Rousseau a pathological desire for celebrity, even more obvious because all such desire was ostentatiously denied. The Duchesse de Choiseul wrote to Mme du Deffand: “He is mad, and I would not be surprised if he expressly committed crimes which did not simply debase him but led to the gallows, if he thought it would augment his celebrity.”86 Even Rousseau's refusal in the last years of his life to appear in public could excite this kind of reader. The Prince de Ligne accordingly said of his interview with Rousseau when he visited him in rue Plâtière: “I will allow myself a few truths here, a bit severe, about the way he understands celebrity. I remember telling him: M. Rousseau, the more you hide, the more you are seen: the more untamed you are, the more public you become.”87 In contrast with the earlier quotes, these words were written a few years before, probably during the Revolution, and Ligne attributes to himself a certain retrospective lucidity. Nevertheless, this text, along with others, reveals the point to which celebrity had become the subject of study at the end of the eighteenth century. It also shows that the phenomenon which for us seems linked to contemporary excesses in the media sphere was already noticeable at that time: at a certain level of celebrity, manifestly refusing all publicity could become an excellent way to stir up public interest.

The Burden of Celebrity

Rousseau did not leave it to his contemporaries to reflect on his celebrity. He made it one of the themes of his autobiographical writings. This is hardly surprising in a writer obsessed by the theme of social recognition and given to introspection about his own destiny. However, though he was one of the first authors to meditate so explicitly on the changes in public recognition implied by celebrity, this aspect of his work has not greatly interested critics, probably because it was not immediately apparent, hidden behind themes of conspiracy and persecution. Nevertheless, as we shall see, when he opened himself to the public as a whole and when he aimed, above all, to project a public figure, that of “Jean-Jacques,” totally different from the real Rousseau, conspiracy became the inverse twin of his celebrity. Using the hallucinatory aspect of nightmare, he described the mechanism of alienation experienced by the famous man: the dispossession of his own being.

Rousseau had aspired to celebrity for a long time, something which seemed to him highly desirable. When he wrote the Confessions, and when it now seemed to him to be a burden, he admitted this aspiration of his youth and realized that when he arrived in Paris he used every means possible to become a celebrity. Above all he was looking for a way to achieve social success and prosperity, hoping that his system of musical notation would help him attain this success: “I persisted in wanting to make a revolution in that art with it, and in that way to arrive at a celebrity which in the fine arts is always joined with fortune in Paris.”88 When he finally became a celebrity, ten years later, the public success of his Discourse at first seemed to him like a happy confirmation of his personal worth:

This favor of the public, in no way courted and for an unknown Author, gave me the first genuine assurance of my talent which I had always doubted until then in spite of the internal feeling. I understood all the advantage I could take from it for the decision I was ready to reach, and I judged that a copyist of some celebrity in letters would not be likely to lack work.89

One sees the apparent paradox in this formulation: Rousseau decided to become a music copyist to live from manual labor, abandoning the literary life but hoping that his literary celebrity would draw customers to him. The contradiction is even more striking when he once again takes up his work as a copyist during the 1770s, at the moment he officially renounced all literary activity and spurned the mechanisms of celebrity. Most of his customers followed him in the hopes of getting close to the wild and famous man.

The contradiction only appears to be so. When he decided to break with the accepted salon model of the man of letters, the one that powerful aristocrats supported, Rousseau built on his celebrity in order to escape the constraints of society life. In contrast with these social constraints, which built reputations and assured the careers of authors, he counted on the support of the public. As we saw from the quarrel with Hume, it was not an inconsequential choice. Rousseau very rarely explicitly admitted his desire for celebrity. However, in an unpublished text, evidently written at the beginning of the 1760s, he wrote: “I prefer for less good to be said about me and that I be spoken about more.”90 What Rousseau designated as “another turn of self-love” (amour-propre) testified above all to a remarkable lucidity in terms of strategic publicity. What difference did it make what they said about him; he just had to be talked about and talked about a lot. Whether they said good or bad things, the essential thing was that his singularity be emphasized: “I would prefer to be forgotten by the whole human race than regarded as an ordinary man.”91 Self-love entails here less a demand for esteem than a desire to be distinguished, to be the center of all public discussions, which is exactly the definition of celebrity. And this, Rousseau adds in a burst of lucidity, needs to be nourished. “Now if I let the public, which has spoken so much about me, act, it would be much to be feared that soon it would no longer speak about me.”92 Soon, however, he became aware of the dangers of celebrity, capable of perverting the most innocent human relations, making every authentic relationship impossible, and he continued: “But as soon as I had a name I no longer had any friends.”93 Celebrity separated him from his friends, brought on jealousies and persecutions. It imposed false human relations because the public persona he had become came fatally between him and others. Therefore, the visits his admirers made to see him became a recurrent motif among Rousseau's complaints. He complained while in Môtiers of receiving too many visits:

Those who had come to see me up to then were people who, since they had some talents, tastes, maxims in common with me, alleged them as the cause of their visits, and immediately introduced matters about which I could converse with them. At Môtiers that was no longer true, above all with regard to France. It was officers or other people who had no taste for literature, who even for the most part had never read my writings, and who did not fail, according to what they said, to have traveled thirty, forty, sixty, a hundred leagues to come to see and admire the famous, celebrated, very celebrated man, the great man etc.94

Empty talk, hypocritical flattery, these visits, which might have been a comfort, were odious. What made them importunate was that they were not based on elective affinities nor on true esteem linked to real interest in his work, but on an unhealthy curiosity which, in the eyes of Rousseau, seemed more or less like spying: “One feels that this did not make for very interesting conversations for me, although they might have been so for them, depending on what they wanted to know: for since I was not mistrustful I expressed myself without reserve about all the questions they judged it appropriate to ask me.”95

While Voltaire, a few kilometers away, welcomed visitors from all over Europe with jubilation, knowing they would recount in their letters and over dinner their visit to the great writer, Rousseau was suspicious of it all, seeing such visitors at worst as perfidious spies, at best as curious people come to see a show. He created an inextricable knot between the consequences of his celebrity and the feeling of persecution that was beginning to consume him, even more painful because in those years he was forced to flee from one refuge to another. Interpreting every show of interest as a menace or a debasement, he rudely spurned visitors. To the Comtesse de La Rodde de Saint-Haon, who ardently wished to visit him, he replied: “I am sorry not to please Madame countess, but I cannot do the honor of the man she is curious to see and she has never stayed with me.” When she insisted, he reproached her concerning the “hyperbolic and outrageous praise with which your letters are filled,” which “seem to be the hallmark of my most ardent persecutors.” Then, refusing to be turned into the showman: “Those who only want to see the Rhinoceros should go to the fair and not to my home. And all the banter with which this insulting curiosity is peppered is but one more outrage which requires no greater deference on my part.”96

The end of this refusal, expressed with such brutal and almost insulting frankness, which he readily adopted when he felt threatened, showed the two themes used by Rousseau to interpret his admirers' desire to see him: that of conspiracy and that of unjustified curiosity. If the first came from a Rousseauistic idiosyncrasy, often called paranoia, the second touched the heart of celebrity mechanisms, which tended to reify the famous person by transforming him or her into a circus act. The rhinoceros comparison, which foreshadows in a striking way the nineteenth-century development of spectacles where all sorts of human monsters and exotic specimens were exposed to public curiosity, thus becoming, as it were, “freak shows,” was less comic than it seemed. This was a reference to the famous Clara the Rhinoceros, who came from Rotterdam in 1741 and was exhibited for almost twenty years throughout Europe from Berlin to Vienna, from Paris to Naples, from Kraców to London, becoming a true international star, the object of books, of paintings and engravings, making her owner enormous sums of money. The memory of Clara, who was shown at the Saint-Germain fair in 1749 and which Rousseau perhaps visited briefly at that time, was no doubt brought to mind again by the arrival in Versailles in 1770 of a new rhinoceros in the king's circus, which also caused a sensation. This obsessive fear of visitors who came to see him as they would to see a circus act – if not to spy on him, then to trick him or make fun of him – became a leitmotif in Rousseau's texts for the last ten years of his life. The testimony of Bernardin de Saint-Pierre, who was very close to him, merits quotation:

Men came from everywhere to visit him, and more than once I witnessed the brisk way in which he dismissed some of them. I told him: Without knowing it, am I not as importunate as these people are? “There is a great difference between them and you! These people come out of curiosity, to say they have seen me, to find out how I live, and to make fun of me.” I told him they came because of his celebrity. He repeated, greatly irritated: Celebrity! Celebrity! The word infuriated him: the celebrated man had made the sensitive man very unhappy.97