7

Romanticism and Celebrity

In 1808, Napoleon met his new ally Tsar Alexander I in Erfurt, in the presence of many European princes. At the emperor's request, Talma also made the trip, along with other actors from the Comédie-Française who gave an air of splendor to the French theater. Napoleon did not stop there: he also requested to meet Goethe. The homage he rendered to the great German writer was seen as an important gesture. The emperor admiringly talked with him about The Sorrows of Young Werther, the work that had made Goethe famous when he was twenty-five, and which Napoleon had read several times. Talma and Goethe built a friendship and saw each other again in Weimar, the actor encouraging the writer to move to Paris, where he promised that his books would be on every table.

Talma, Napoleon, Goethe: the meeting in Europe of these three celebrated men, an actor, a statesman, and a poet, is a powerful symbol of the effects of celebrity at the beginning of the nineteenth century. The pre-eminence of the emperor in this context is unchallenged. But the bond established between these great figures of intellectual, political, and cultural life was not the usual relationship created by patronage. “You are a man,” the emperor supposedly said to Goethe when he met him. Years later, the writer was still wondering how to interpret the somewhat mysterious sentence, although it well described the personal aura which surrounded him. Napoleon, by receiving Goethe, was a sovereign honoring a poet and also a reader satisfying his desire to meet a celebrated writer.

Over the space of ten years, Napoleon, Goethe, and Talma would all die, all three gone between 1821 and 1832. Besides having in common their immense celebrity, they embodied the transition toward the romantic myth of the demiurge hero, the creative genius, and the virtuoso actor. Today, the term “Romanticism” has become a cliché in literary history, hackneyed through overuse. Nonetheless, it is still useful for designating, in broad strokes, the cultural context of the first half of the nineteenth century. It was first of all marked by an acceleration in the development of printing and by the birth of the culture industry. Contrary to what traditional periodizations assume, there was no real rupture during this period but rather a deepening change that had already begun in the preceding century. Newspaper editions grew immensely, encouraged by the steam presses capable of printing many millions of pages an hour, and books became a more common consumer product for the new middle class. The entertainment economy continued to break the mold and in Europe aligned itself with the British style: freedom from royal patronage, multiplication of public concerts and commercial enterprises, and a growth in publicity that transformed cultural life in the cities. Romanticism as a literary, artistic, or musical movement was largely dependent on the accrued media development of cultural life.1

A second aspect of Romanticism was the importance given to the expression of feeling, to the acceptance of subjectivity as a construct of personal identity, and the search for authentic personal relationships. It included the idealization of love, the sublime, and strong emotions, but also a generalized culture of introspection, all of which were rightly associated with the movement. This new sensibility was especially evident in the omnipresence of the artist, the poet, in his work. Lyrical poetry lent itself well to the publication of intimate feelings, unthinkable one or two generations earlier. Obviously, the question was not whether these feelings were sincere or real, but realizing that they transformed both the concept of “the self” and the official forms of literary and musical communication. Even though he did not really reveal himself, the writer appeared to be a sensitive and misunderstood genius, a powerful being or a melancholy hero.2 This new visibility of the artist was accompanied by an acceptance of the subjectivity of the reader or listener. The new aesthetic was not evaluated according to classical rules or to the social hierarchy of the Ancien Régime, but rather by public pleasure. Stendhal understood this very early: “Romanticism is the art of presenting the people with literary works that give them, in light of the actual state of their habits and beliefs, the most pleasure possible.”3

In spite of the apparent contradiction between these two traits of Romanticism – the mediated aspect of cultural life, the ideal of an immediate meeting between the creator and the public – they are complementary. Clever booksellers and impresarios who specialized in new publicity techniques encouraged the meeting between artists eager to put their “self” on show, suffering or triumphal, and readers ready to be enthusiastic and to identify with them. Often, the romantic artist was both a master of self-promotion and highly sentimental. The public, however, was not entirely fooled. The culture industry, having supported the birth and then the triumph of Romanticism, was also the object of its distrust, shown by the recurrent denunciation of industrial literature, bad music, or street theater. Celebrity was caught in these contradictions. It progressively imposed itself as a characteristic of literary, artistic, and musical life, but it suffered from the duality of an affective one-to-one between an artist and his public and the management of the more prosaic realities of mass culture. It was not just the political forms of this phenomenon that were affected by the changes: sovereign or revolutionary leader, everyone now had to deal with the constraints of publicity.

Byromania

A few years after Erfurt, the momentous irruption of Lord Byron onto the public stage was, undeniably, an important step in celebrity culture. Byron's exceptional European notoriety was intensely described, analyzed, and decried. The Byron moment was Rousseau all over again, with an even greater impact.

George Gordon was the heir of Scottish lords and an old English aristocratic family. After publishing several unremarkable satirical works and traveling to Spain and Greece, he hesitated between a political career in the House of Lords, in line with his social status, and the more uncertain career of a poet. In 1812, he published Childe Harold, a long poem with an archaic tonality that described the adventures of a melancholy knight along the banks of the Mediterranean. It was a great success. “This poem appears on every table,” the Duchess of Devonshire noted, and Byron “is really the only topic of almost every conversation.” Byron became a fashionable poet, an artist everyone talked about and everyone wanted to see. Anne Isabella Milbanke, who met him at this point and married him three years later, was struck by the excitement that surrounded the young man. To describe the effects that seemed to her derived from collective hysteria, she invented the term “Byromania.”4 Over the following months, the triumph continued. Byron's new poems again dealt with the theme of a romantic and blasé hero and, as before, they had great success. The Corsair ran to ten thousand copies the day it came out in February 1814, a prodigious number for the period.

But already it was clear that Byron's success was not just a literary phenomenon. All the interest centered on his personality, arousing adulation or disapproval. His agitated love life and much disparaged morals created scandal. His affairs were the object of all kinds of speculation. His marriage was disastrous, his wife obtaining a separation after a year. Caught in a maelstrom of lurid rumors, Byron left England in 1816 and never returned. What happened next is as much a part of romantic legend as it is of history: the melancholy lord continued his sexual conquests and his poetry along the banks of Lake Geneva, then in Venice and Pisa, before joining with the Greeks in their struggle for independence and at thirty-nine dying in Missolonghi. This unexpected death created shock waves throughout Europe. In England, the press that had so vilified him was now full of praise; teenagers who had not known him were in despair. On the Continent, young fashionable men ostentatiously wore mourning dress. Even though the poet died of high fever without having really seen combat, he became an heroic figure for European youth, a liberator who combined the talents of a poet and the courage of a soldier, often associated with Napoleon as part of the romantic hero cult. Byronism left the realm of celebrity and entered the universe of myth.5

While alive, Byron's celebrity went beyond the normal literary recognition of his poetic talent. It grew between 1820 and 1830 and he became the most successful of all romantic poets for an entire generation in France, Germany, and England. But his first success, during his English years, brought together literary triumph and celebrity scandal. This type of celebrity, fed by rumors and court trials, was characteristic of provocative people in polite English society.6 The success of Childe Harold was fanned by unhealthy curiosity kept alive through rumors published in the press. Byron was suspected of having numerous mistresses; his homosexuality was denounced, as well as his incestuous affair with his half-sister. The failure of his marriage led to an electrifying trial. As early as 1821, the London Magazine claimed that interest in Byron was more “personal” than “poetic.”7

This interweaving of literary and celebrity scandal was effective because Byron purposely never ceased to combine his life with his work. His heroes all seemed related (Harold, the Corsair, Giaour, Manfred, Don Juan): they were adventurers, potentially very erotic, profoundly melancholic and disenchanted, sometimes hopeless, all of them living in exotic places. But the Byronic hero was also embodied by Byron himself, with his combination of great beauty and a physical handicap (he was born with a club foot), his taste for far-away places and a secret melancholy that consumed him, his open revolt against social conventions and his ambiguous morality – all of which he ostentatiously cultivated. At the same time, he invented and incarnated the idealistic and disillusioned rebel, refusing to bend to ordinary moral conventions, showing himself to be sardonic, seductive, and unhappy. At the very least, besides his immense impact on the European romantic culture of the nineteenth century, Byron also profoundly affected popular culture. Numerous stars in the twentieth century would again adopt these same romantic characteristics.

Byron skillfully maintained the autobiographical dimension of his poems. The first version of Childe Harold, to all appearances, was a transposed narrative of his Mediterranean travels. The medieval fiction was only thinly developed, and in the two songs he added in 1816, he cleverly multiplied allusions to his love affairs. In Manfred, he inserts a very veiled allusion to his half-sister. Numerous readers read Byron's poems in the hope of better understanding his secrets and his mysteries, his flaws and his prominence, as a way to satisfy their curiosity about such a celebrated and fascinating figure.

Byron's celebrity was not a biographical episode apart from his poetic work and his place in literary history; it was an essential element. As a legacy, Byron left not only the image of a romantic hero, melancholy and in revolt, or a body of poems that would be admired by a generation of readers, but also a form of almost voyeuristic poetic exchange between the curious reader and a shameless author who risked being accused of exhibitionism. The poetic fiction turned out to be a good way to feed the system of celebrity because of Byron's clever ability to carefully handle one aspect of the ambiguity. There is no doubt that Childe Harold, the Corsair, Manfred, or Don Juan were all doubles for Byron; but what exactly is autobiography and what is fiction? Byron made a game of this ambiguity, moving the curiosity of the readers from biographical revelations – the press took care of that – toward personal avowals of feeling and various states of mind, and thus toward a more empathetic relationship, a more sentimental one, with the author and his characters. This ambiguity maintained a mysterious, secret aspect that stimulated the interpretive effort of readers. It encouraged a “hermeneutics of intimacy,” readings that attempted to gain intimate knowledge of the author through an interpretation of his work.8 Ambiguity was a powerful resource for Byromania, weaving together the success of the poems, public curiosity about the writer, and the desire of many readers to gain intimate access to this sensitive and tormented soul.

This complex cultural phenomenon of celebrity was not solely based on an immediate encounter, sudden and passionate, between an author and his public, which seems to be indicated by Byron's famous sentence, often cited: “I awoke one morning, and found myself famous.”9 Actually, this sentence was only reported by Thomas Moore in 1830 and is perhaps apocryphal; at any rate, it was reported after the fact. It does, though, maintain the myth of immediacy that contemporaries as well as historians complacently upheld. If celebrity for Byron was precipitous, it was neither sudden nor spontaneous.

John Murray, Byron's editor, played a very important role in his success, employing subtle methods of marketing. Along with the first edition of Childe Harold, he inserted numerous ads in newspapers, but also sold a relatively luxurious and expensive edition aimed at a small number of the elite.10 Moreover, the success of his first book was advertised by Byron's peers, members of polite society who knew him by name, if not by reputation, who shared with him a taste for archaic poetry, for the Grand Tour and the Mediterranean countryside, those who were likely to meet him in person in London social circles. That Byron found his first unconditional admirers among members of polite London society was obviously not inconsequential: it is there that the mix of literary success and the celebrity of scandal took root, giving a certain specificity to the early Byromania. It is where Byron first met the capricious Caroline Lamb, who professed an uncontrollable passion for him. Later, Byron's celebrity grew among the urban bourgeoisie. From that time forward, his work sparked a considerable number of imitations and parodies, while the Byronic hero became a standard reference for the new educated classes.

Byron was also a face made familiar by the circulation of a large number of portraits, so widely distributed that John Murray told Byron: “Your portrait is engraved and painted and sold in every town throughout the kingdom.”11 Preoccupied by his physical appearance to the point of following a diet to scrupulously control his weight,12 Byron wanted to control his image by having engravings made from paintings he himself commissioned from reputed artists, but these artists generally portrayed him as serious and melancholic. Very quickly, he had to admit that his image had escaped him and that numerous portraits, more or less resembling him, had multiplied to satisfy the public demand, creating an icon that was instantly recognizable: the silhouette of a young man, generally seen in profile or a three-quarter pose, as in the first portraits, with wild black hair and wearing a long white scarf.

The celebrity of Byron was known throughout Europe, well before his death. Writers played an important role in this. Goethe admired the English poet and never ceased to quote him in his conversations with Eckermann: “I was filled with timidity and tenderness; if I had dared, I would have burst into tears and kissed Lord Byron's hand.”13 After 1818, infatuation with the disenchanted and desperate poet grew and included a larger and larger public, even before the translation of his poems; French newspapers repeated anecdotes written up in the English press, often focusing on Byron's debauchery. The English presented him as a poet of genius, evil but desirable. Mme Rémusat, reading Manfred, wrote to her son:

I am reading Lord Byron; he charms me. I would like to be young and beautiful, without any restraints: I think I would go find this man and tempt him back to happiness and virtue. In truth, I think that this would be at the expense of my own. His soul must cause him a great deal of suffering, and you know that suffering always attracts me.14

Attempting to describe the power of Byron over his public, metaphors increased: opium, alcohol, madness. Such excitement seemed to defy explanation.

Byron no doubt enjoyed the prestige his success and celebrity afforded him. But he also felt the constraints. His decision to leave England in 1816 was motivated by a desire to find some peace and to escape the devouring publicity. His celebrity, however, preceded him. Visiting near Lake Leman, he was invited by Mme de Staël to a “family dinner”; there he found a room full of guests who were patiently waiting his arrival and who shamelessly stared at him as though he were “some outlandish beast in a raree-show.” One woman, overtaken by fear and emotion, fainted.15 This story, part of the conversations published by Thomas Medwin when Byron died, testified both to the curiosity aroused by the exiled poet, and to the various narrative themes that illustrated the servility toward celebrity seen earlier with Rousseau and Siddons: the celebrity trapped by an invitation and surrounded by a crush of curious people, the comparison with circus animals, the confusion involved with being the center of attention. These themes progressively became commonplace, repeated and analyzed over and over again.

Prestige and Obligations

Like Rousseau before him, Byron became the archetype of a celebrated writer, one whose renown, for better or worse, rose above the level of his literary reputation to that of a person half-real, half-fictional, on which the collective imagination focused at will, a public figure confronted with the mechanisms of celebrity. Writers in the first half of the century were obsessed with Byron's destiny, a career they sought to imitate or distance themselves from. Chateaubriand, obsessed by his own public image, never ceased to measure himself against this famous contemporary, following him to Venice, criticizing his tastes, or enjoying a letter the young Byron wrote him when Atala was published. Chateaubriand also experienced his own Childe Harolde, an inaugural moment when success arrived for the unknown writer and threw him without warning into the headlights of the press.

He had been an unknown, and the discreet publication of the Essai sur les révolutions in 1797 did not bring him renown. But the publication of Atala in 1801, with a clever press campaign orchestrated by his friend Fontanes, brought him enormous success. Fierce criticism by the most established literary men such as the Abbé Morellet added to the book's attraction. Chateaubriand took off.16 He embodied an aesthetic rupture as well as an ideological one: the lyrical evocation of beauteous landscape, a sonorous language, and a desire for a return to spirituality and its mysteries which caused virulent debates on the importance of religion and the legacy of the Enlightenment and the Revolution. But he also knew how to cleverly manage a notoriety that had suddenly quenched his thirst for recognition after years of exile. Several weeks after the publication of Atala, he hosted a grand dinner party in a restaurant and invited editors from all the Parisian newspapers. “No one is aware of how hard he worked for his renown,” Mathieu Molé remarked of the dinner.17 A few years later, during the Hundred Days of Napoleon, Jaucourt excitedly wrote to Talleyrand: “M. de Chateaubriand is obsessed by the publicity demon.”18 This taste for celebrity, this excessive attachment to his public image, would soon become one of the proverbial aspects of his personality. Rewriting his Mémoires almost forty years later, when the system of celebrity had become even more visible, he returned to that inaugural moment and devoted a lucid, funny, and melancholy chapter to it.19

After recalling the importance of the press, a necessity in preparing the reader and introducing the author before publication of the book, Chateaubriand insisted on the effect of novelty and surprise, on the “strange aspect of the work” that aroused controversy and debate. Celebrity was not the result of unanimous admiration, but rather a success due to scandal that caused debates and quarrels, apologies and sarcasm, endlessly creating a buzz around the book and the author. The applicable vocabulary included words like “noise,” “clatter,” and “fashion.” Far from being the result of a calculated climb toward the heights of literary prestige, celebrity appeared to be an “emergence,” as violent as it was sudden.

Chateaubriand's sudden celebrity, like that of Byron, already seemed commonplace, a formula. It had the sense of a revelation, an immediate anointing, far from the slow, constructed careers of professional literary men. In this, it was perfectly suited to the romantic myth of the impetuous hero, similar to his military counterpart: the one like the other demanding swift triumphs. But success could also be a flash in the pan, as ephemeral as it was sudden. Nothing guaranteed it would be different from other spectacular successes that went nowhere and seemed incomprehensible a few years later. In a text dated 1819, Chateaubriand is already suspicious:

An author does not rejoice in this renown, the object of all his desires, which seems to be as empty as is happiness in life. Can it console him for the calm which has been stolen from him? Will he ever know if this renown is a matter of partisanship, to particular circumstances, or if it is truly glory based on real merit? So many miserable books have had such a prodigious popularity! What is celebrity worth that is so often shared with a crowd of mediocre and dishonorable men?20

For romantic writers confronted with the success of their writings, this distinction between celebrity and glory was a recurrent theme. When Byron died, John Clare published an essay on the “popularity” of writers based on the conviction that this was not due to real glory, that “the trumpeting clamour of public praise” did not always mean eternal renown.21 This was a classic theme, the legacy of Cicero and Petrarch, but it had taken on a new form. It was no longer possible in 1824 to totally disdain popular taste and public judgment. What Clare had in mind in writing his text was the prodigious celebrity of Byron, a poet he profoundly admired and whom he considered to be the equal of Shakespeare. Was he an exception to the general rule? Only the future would tell if Byron's celebrity, rapid and brutal as a storm, would acquire the calm and serenity of long-lasting and eternal glory. In fact, the traditional contrast between fictive and ephemeral reputations and posthumous glory was troubled by a new element: the common people, who loved simple, natural poetry. Thus, the popularity of contemporary authors was profoundly ambivalent: it could be related to the effects of fashion, to the role of literary critics, to the excessive enthusiasm of the public, but also a matter of common fame, something the romantic poet could not despise, although it was not as desirable as unanimous praise from posterity.

For anyone having experienced it, celebrity was both heady and worrying; it was a recognition and a constraint, a first step toward glory, but also a trap that threatened to close in on any author who was too vain. When he did a rewrite of the third volume of his memoirs in 1814, Goethe recalled the “prodigious effect” of his The Sorrows of Young Werther, the success which had made him a European celebrity at twenty-five. He had felt great pleasure at being admired as “a literary meteor,” but he also experienced the importunate curiosity of the public, without being able to separate out the part that was pleasure from the part that was disagreeable.

The greatest happiness or the greatest unhappiness was that everyone wanted to know who this unique young author was who had produced such an unexpectedly good book. They wanted to see him, talk to him, even from afar, to learn something about him, and in this way he experienced an excessive eagerness, sometimes agreeable, sometimes uncomfortable, but always meant to entertain him.22

All his efforts afterward were aimed at refining his celebrity, retaining only its advantages. When he was on a trip to Italy, he went incognito, then he consciously transformed his literary celebrity, vaguely scandalous, into a more classic renown, that of a courtesan author, a court counselor in Weimar, already glorified while alive by national admiration, not public curiosity. He never totally succeeded, of course, and his last work, like the conversations with Eckermann, showed some bitter-sweet opinions about the torments of celebrity, “almost as harmful as disrepute.”23 It was, in spite of all the satisfaction of self-love, an enormous challenge for the writer, who was obliged to play a public persona, to keep his opinions to himself about others and above all to sacrifice his poetic work to his social life: “If I had stayed more away from public life and business, if I had been more able to live in solitude, I would have been happier and I would also have been able to do more as a poet. […] When you have done something that pleases people, it prevents you from doing it again.”24

Chateaubriand said very much the same thing about the heady nature of celebrity and its false pretenses. Once Atala was published, he ceased to be his own man: “I stopped living for myself and my public career began.” But there was another side to it: if success brought joy to the celebrated man, it also imposed constraints.

My head was spinning: this was not the joy of self-esteem; I was drunk. I loved glory the way one loves a woman the first time. However, coward that I was, my fear equaled my passion: like a conscript, I walked into the fire. My primitive nature, the doubt I had always had about my talent, made me humble in the midst of my success. I escaped from my brilliance: I stood apart, trying to reject the halo that crowned me.

Nobody has to believe this story told retrospectively by Chateaubriand about his timidity. Nonetheless, the text in general is striking because it is careful not to separate these two aspects: the “stupid infatuation with vanity” that drives a celebrated man to delight in the public uproar he arouses, and the worry which this sudden notoriety engenders, the impression of no longer recognizing oneself, the desire to escape the stares of others in order to find oneself again. Chateaubriand said he sometimes felt the need to lunch in a café where the owner knew him by sight without knowing who he was, a place he could eat protected from the gaze of curious people. He would be recognized there as a regular and not as a literary celebrity. Even here, he never forgot that he had written a successful book and he looked for literary critiques in the press, but at least felt at peace thanks to the caged nightingales, whose songs relaxed him. The presence of these nightingales, in a scene where Chateaubriand is looking for a way to escape the hold that celebrity has over him, reminds one unmistakably of a scene in the Confessions, when Jean-Jacques is sleeping under the stars and listening to nightingales. In case the reference is not clear enough, Chateaubriand carefully notes that the owner of the café is called … Mme Rousseau!

A few lines later, reference to the author of the Confessions is made even more explicit when Chateaubriand casually remarks on the success he has with women, to whom he owes his celebrity, “young women who cry over novels” along with a “group of Christian females” who were eager to seduce him.

J.-J. Rousseau talked about the declarations he received when his book La Nouvelle Héloïse was published and about the conquests he was offered: I do not know if anyone would have given me empires, but I know that I was drowning in a flood of perfumed love letters; if these letters were not today those of grandmothers, I would not know how to recount with proper modesty how they fought over every word I wrote, how they swooped up any envelope of mine, and how, blushing, they hid it, lowering their head beneath the veil that covered their long hair.

Celebrity was now eroticized. Chateaubriand wrote about the reciprocal seduction that was established between the celebrated writer and his admirers, men and women, written in a melancholy humor that was understandable given the years that had passed, but not without vanity. He focuses with false modesty on the dangers represented by the “beautiful young girls of thirteen and fourteen,” “the most dangerous; because not knowing what they want nor what they want of you, they seductively mix your image into a world of fairy tales, ribbons and flowers.” Real or imagined perils? This world of fairy tales expressed what was essential: for the author, as well as for his young admirers, celebrity was based on a mirage. It created a crack in the rational nature of social relationships.

The question of celebrity, the pleasures it procured and the worry it stirred up, was no longer the new and almost incomprehensible phenomenon it still was in the middle of the eighteenth century. It was a reality now, well rooted in cultural life, for which Rousseau appeared to be the tutelary figure, the first to have described it in detail.25 Moreover, the shift was obvious. Where Rousseau had experienced the curiosity of the public as a form of alienation, the impossibility of being authentically oneself, Chateaubriand took up the theme with more distance and detachment. His own error, Chateaubriand wrote, was not in wanting to be a celebrity, but in claiming that he was not changed by it. In that resided the vanity of the author, the obviously illusory hope that success would leave him untouched, would let him live simply, without transforming him into a public person.

I thought I would be able to savor in my heart, in petto, the satisfaction of being a sublime genius, not wearing, as I must today, a beard and outrageous clothes, but I could remain dressed like ordinary people, distinguished only by my superiority: useless hope! My pride should be punished; I learned this lesson from politicians I was forced to know: celebrity is an advantage with moral obligations [un bénéfice à charge d'âme].

“Un bénéfice à charge d'âme”: In French, it is a stunning expression and profoundly ambiguous, since it refers to the work of a priest taking care of souls. Irony can be read in it, since the obligations of celebrity that Chateaubriand lists are social and worldly constraints, like dinners in the country house of Lucien Bonaparte which he could not avoid. A priest taking care of souls might well have been, for a romantic writer, the ironic inversion of spiritual magisterium, especially for the author of the Génie du christianisme. This phrase also evokes the special bond between a celebrated man and his public. The shadow of Rousseau hovering over this text prepares one for such an interpretation. More subtly, Chateaubriand follows the sentence with an account of his meeting with Pauline de Baumont, already sick at the time, who would become his great love up until her death two years later. “I only knew this afflicted woman at the end of her life; she was even then marked for death, and I dedicated myself to her suffering.” Dreamy adolescents had given way to another admirer, a dying woman.

Celebrity, for those who are the object of it, is not simply an attribute, the projection of a public image on the world; it profoundly transforms the celebrated person because it modifies the way others look at him or her, forever changing the person's perception of self and the nature of relationships with contemporaries. Chateaubriand's force, in this text, is to combine the magical memory of his public epiphany and the critique of an old man who had very often been reproached for his obsession with renown. Ironically, at the moment he finished his Mémoires, he found himself once again constrained by celebrity; he learned that the editor to whom he had sold the rights had, in turn, granted the rights to Émile de Girardin so he could publish them in serialized form in La Presse. Scandalized, Chateaubriand protested without effect that “his ashes belonged to him.” In fact, the story of his life no longer did belong to him; harried by financial worries, he had sold the rights for a fortune and his life's work was now in the hands of advertising marketers.

Women Seduced and Public Women

When Chateaubriand referred to visits from enamored women admirers, he encouraged a platitude, the power of seduction associated with celebrity. Byron was obviously the great embodiment of this eroticization of celebrities. Specialists have focused on letters he received from readers where an imaginary acting out of sexual fantasies is imprinted like a watermark. The letters from Isabelle Harvey, for example, shot through with trembling desire, seem to illustrate the hold that Byron had over the feminine imagination: “You tell me I am deluded in my imagination with regard to the sentiments I bear you. Not matter if it be illusion, how much more delightful it is than reality. I abjure reality for ever.”26 Byron saved these letters, which were published and analyzed. Some are identifiable, others anonymous.

Might not the idea of a seductive woman, dreaming of meeting a celebrated poet or virtuoso musician and offering herself to him, be a masculine fantasy that very soon became commonplace? In the 1820s, at the height of Byron's success, English critics developed the theory of an hysterical female audience, women who were actually ill, possessed by an epidemic of enthusiasm that was vaguely literary and erotic. This collective pathology, according to these critics, was the sign of a grave social and moral disorder, and the denunciation was picked up by Victorian authors in the second half of the century, as much as by university critics, careful to distinguish Byron's legitimate work from the superficial effects, incomprehensible and grotesque, of his celebrity.27 True, Byron, like Chateaubriand, and like Rousseau before him, did receive numerous letters from readers. The archives are, however, slanted because Byron carefully kept only the most admiring letters, the most flattering ones: “Don't we all write to please [women]?” he asked.28 As for women readers, their letters often showed them to be more playful than passionate. They claimed a familiarity with the author, identified readily with his characters, but they kept an amused distance from their own epistolary adventures. Some anonymously constructed a symmetrical game, revealing aspects of their private life to Byron, then later implying a doubt about their authenticity, as Byron did in his books.29 The result was that when these readers claimed that they wanted to cure Byron of his melancholy, they were partly playing a game, wanting to use the characteristics of fiction as their model and having fun with the ambivalences, as was also the case with Rousseau's readers.

A female reader seduced by a celebrated writer to the point of entering into an epistolary relationship with him became herself a romantic figure. In 1844, while Chateaubriand was revising his Mémoires, Balzac published a novel, Modeste Mignon, in the Journal des débats, in which a young provincial girl starts a correspondence with a celebrated Parisian poet, Canalis. The novel was in step with the times, an ironic reflection on literary prestige and the effects of celebrity. The previous year, the letters of Bettina von Arnim to Goethe had been translated into French; Balzac, who wrote a review of the correspondence, gave his heroine a name borrowed from Wilhelm Meister, Bettina; the allusion could not be clearer. Publication of the Bettina letters drew attention to the practice of writing letters to celebrated authors, which had not abated since Rousseau.30 Balzac knew perfectly well about this practice not only because he himself had received letters from men and women readers, but also because his own relationship with Mme Hanska, to whom the novel was dedicated, started out by correspondence.

In the novel, Modeste Mignon's interest in Canalis develops on two levels. The young woman's passion for contemporary literature and in particular the great authors, from Rousseau to Byron and Goethe, leads her to an “absolute admiration for genius.” In her sad provincial life, literature offered her a refuge through an imaginary world which she filled with romantic heroes and where she could be the heroine. References to Byron are emphasized, and when Modeste takes a walk around the port of Le Havre to see the English disembark, she regrets not seeing a “lost Childe Harold.”31 The spark that ignited this romantic desire was, to the contrary, “a futile and silly piece of luck”: the discovery of a portrait of the poet.

Modeste happened to see in a bookseller's window a lithographic portrait of one of her favorites, Canalis. We all know what lies such pictures tell, – given that they are the result of shameless speculation, seizing upon the personality of celebrated individuals as if their faces were public property. In this instance Canalis, sketched in a Byronic pose, was offering to public admiration his dark locks floating in the breeze, a bare throat, and the unfathomable brow which every bard ought to possess. Victor Hugo's forehead made more persons shave their heads than the glory of Napoleon killed budding marshals.32

With somewhat forced irony, Balzac introduced into the heart of his story the base commercial motives that were the source of the increase in mediocre images, a certain ambiguity residing in the fact that the images were both vulgar, in terms of publicity artifacts, and grandiose, because they reproduced the recognizable traits of real genius; Byron and Hugo were not quoted by chance, nor, of course, was Napoleon. Such was the force of celebrity: images without quality, a cynical and commercial exploitation of the notoriety of great men, aroused sincere enthusiasm. Modeste is seduced by this “face made sublime through a marketing necessity,” and undertakes to write Canalis. But it is his male secretary who responds in place of the poet, and he becomes involved in a correspondence with her that quickly turns amorous. This framework allows for reflections on celebrity, notably when the real Canalis, who is interested in the sudden and unexpected fortune of Modeste, goes to Le Havre and squanders the aura of his celebrity in just a few days. He discovers that if “public curiosity is wildly excited by Celebrity,” the interest does not last; it is fleeting and cannot survive a meeting with the actual person: “Glory, like the sun that is hot and luminous at a distance, is cold at the summit of an Alp when you approach it.”33 Genius in itself is not at all seductive; it is ruminations about celebrity that give rise to an illusory glamour.

The end of the novel sees Modeste, enriched by the unexpected and triumphal return of her father, choosing between three suitors: an aristocrat, representing the traditional elite; the celebrated poet; and the wise secretary, Ernest de la Brière, who has neither riches nor genius to offer but wins out finally because of the sincerity of his feelings. A bourgeois epilogue? Doubtless, but the subtlety of Balzac consists in suggesting that Modeste's attraction to Canalis did not concern crazy passion aroused by some verses and a portrait. Modeste, less naïve than she appears, was careful to find out about the poet's conjugal state. She used the mediated celebrity as a resource for dreaming, to pull herself out of the disappointing and uninteresting world that surrounded her, to become more than a passive reader, to participate in a romantic game and take control of what was happening to her. Her final decision was in no way thoughtless and impetuous. Dreaming about an idyll with a poet whose portrait adorned bookstore windows, she found a place in a media-hyped universe that was not hers, but when it came to choosing a husband she took her time deciding, enjoying the competition between suitors and opting for the most suitable one.

Nonetheless, the theme of celebrated men seducing young women who might anachronistically be called groupies revealed that access to celebrity was uneven. With Chateaubriand, as with Byron, the celebrated man seduced his female public and then had to protect himself from the excessive reactions. On the other hand, a celebrated woman was disgraced, illegitimate. Her potential for seduction was seen as inherently immoral, putting her on the same level as prostitutes and courtesans. It is no coincidence that the term “public woman” was used for a long time to mean prostitute. For literary women, public exposure was a threat to virtue and modesty. In 1852, Harriet Beecher-Stowe had immense success with Uncle Tom's Cabin, an abolitionist bestseller; in the first year three hundred thousand copies were sold throughout the United States and one and a half million in Britain. During a promotional tour in England arranged by her editor, she often sat in the area reserved for women, protected from public stares, letting her father and brother go to the podium and speak for her.34 At the same time, however, signs of an evolution were felt. After the success of Jane Eyre in 1848 and after sowing seeds of doubt about her identity and her sex, Charlotte Brontë became extremely popular. When she died in 1855, Elizabeth Gaskell published a biography, partly fictionalized, which strongly affirmed the legitimate image of female writers.

In France, the case of George Sand is emblematic. Celebrated for her novels, but also for her public life, her political activities and her tumultuous affairs, George Sand suffered a flood of attacks. However, she had always been careful to publish under a pseudonym, starting with her first novel in 1832; she chose the male first name George, which in turn inspired another woman author, George Eliot.35 Like many women authors, she actually wanted to publish anonymously but her editor pushed her to find a pseudonym for commercial reasons. In fact, despite the success of Indiana, she at first managed to maintain a certain anonymity. She even succeeded in sustaining for a while a certain question about her gender, at least for those who only knew her name. In Histoire de ma vie, published twenty years later, at the height of her celebrity, she re-affirmed this desire for anonymity, although it is not easy to distinguish between compulsory modesty and sincerity:

I would have chosen to live obscurely, and as I had succeeded in remaining incognito during the interval between the publication of Indiana and Valentine – so that the newspapers always referred to me as monsieur – I flattered myself that this little success would not affect my sedentary habits or my small circle of intimates, composed of people as unknown as myself.

But she added that she was quickly disillusioned in this hope. She had visits from the curious, from beggars, from kindly as well as malicious persons. “Alas! soon I was to long for peace, in that as in everything else, and to seek solitude in vain, as did Jean-Jacques Rousseau.”36

In Les Célébrités du jour, a collection of biographies published in 1960, Louis Jourdain and Taxile Delord included a preamble on female celebrity before presenting the portrait of George Sand, the only woman artist in the collection. What could be said about a celebrated woman whose life was surrounded by scandal and rumors? In this case, the usual argument used to justify publicity for a celebrity ran up against the more classical issue of feminine modesty, which rendered indiscreet any investigation into her private life:

What right does a biography have to penetrate the private life of a woman, conversing with the public about her love life or her antipathies, her struggles and her weaknesses? But let us suppose that this woman has exceptional talent; she is an artist or poet, she sings, she writes, she paints, she sculpts, and the public has a very legitimate desire to know who she is, how she lives, who she loves, how she suffers. That the public feels this way is possible, but that the public has the right to satisfy that desire and, in so doing, to scrutinize the intimate existence of a woman, to analyze each of her actions or words, to pore over her affections in order to taunt or pervert them, we do not agree.37

This gender structure for celebrity, the constraints of which weighed the most heavily on women authors, lasted a long time. At the end of the century and even during the Belle Époque, women writers would always be torn between the desire for success and celebrity, on the one hand, and the values of modesty and devotion to female domestic duties, on the other. Was it possible to become a public figure without running headlong in opposition to social norms? It became so difficult that any too obvious sign of authorial modesty was eventually perceived by the critics to be a secret desire for celebrity. More than one female author found herself trapped by this frightening contradiction.38

Virtuosos

As in the preceding century, theater remained a privileged vehicle, really the only legitimate one, for female celebrities, since the international tours of the Malibran, a Spanish opera singer, who sang in opera houses all over Europe, up until the success of Mlle Mars and Rachel on the stage at the Comédie-Française. After her success in Phèdre, Rachel successfully negotiated extremely favorable financial conditions at the Comédie-Française, to the great annoyance of other cast members, who had to bow before the celebrity of the tragedian.39 Her death in 1858 elicited a deluge of praise, anecdotes, and biographies, and a race for autographs and intimate stories. The director of the Figaro had, several weeks earlier, prepared an article about her and he profited from her death to publish a special issue “composed of anecdotes, and an autograph by the illustrious tragedian, along with fifty new letters, the spiciest ones and the most varied.”40

In cities, the theater continued to occupy a central role in cultural life, as it had since the start of the eighteenth century, providing the public with stars. In Paris, while Rachel triumphed in tragic roles, Frédérick Lemaître played opposite Marie Dorval in comedies and popular dramas, and in street theater, transforming the bandit Robert Macaire into a comic character. The term “star,” imported from English, began to designate actors with top billing. In London, Edmund Kean, the unchallenged star of Drury Lane, did not attract attention uniquely because of his theater performances, but also because of the scandalous public persona he had created. Born into the theater, Kean came from an entirely different social stratum than Byron, but, like him, he owed his celebrity to the conjunction of a rapidly recognized talent and a turbulent private life well known to the public. A few years after Byron's impressive divorce, Kean was convicted of adultery in the wake of a trial that occupied the British press for several months. The comparison ends there. Kean did not embody a romantic, melancholy character, but rather an histrionic and capricious figure always eager to transform his life into a spectacle, casually feeding the craziest rumors by his extravagant comportment: the newspapers recounted his drunken sexual brawls, claimed that he fed a tame lion on live animals, and that he participated in boxing matches barefisted.41 A Shakespearian actor and fractious star, Kean made an impact on his contemporaries in England, where the whiff of scandal permanently accompanied him, but also in the United States, which he visited on two occasions, and in France. Alexandre Dumas devoted a play to him three years after his death.

Ultimately, there was nothing very new in this. The real romantic revolution in the realm of celebrity was less a matter of the theater than it was of music. There were already stars in the eighteenth century, composers like Handel, Gréstry and Gluck, and the castrati singers Farinelli and Tenducci. But music was marked by its religious origins and by the courtly or aristocratic context in which it was most often played, so much so that it remained the privilege of a cultural elite. In spite of their success, neither Gluck nor Haydn was celebrated beyond the narrow confines of music lovers and patrons. Young Mozart, of course, amazed London and Paris audiences during his first European tour at age six. His celebrity, however, was based on being a child prodigy who seemed to embody new theories about the innate character of creative genius,42 and the surprise and astonishment faded as he got older. If his musical reputation remained high among music lovers, in spite of his setbacks at Salzburg and up until his late success in Vienna, he had to resign himself to creating less enthusiasm than before. He was bitterly disappointed by the Paris welcome he received in 1778 and complained that audiences, often busy socialites, were relatively indifferent, showing only polite interest.43 In contrast, the first half of the nineteenth century saw the triumph of great musical stars. The increase in public concerts, more or less freed from aristocratic patronage, and the invention of individual recitals changed the social conditions of performances.44 Music no longer had the same status: it had become a pure art form, an ideal means for expressing feeling. Beginning with Gluck, this new relationship reached its apogee in the years 1830–50 with Liszt's great success. From Vienna to Berlin, from Pest to Paris, and from Naples to London, concerts attracted large audiences enthusiastic about the new music, the composers, and their performances. “Paris is drowning in a flood of music, there is hardly a house where one can be saved as on Noah's Ark from this sonorous deluge; at last, noble music has inundated our life entirely,” noted Heinrich Heine with amusement in his Parisian chronicles.45

This was the moment when Beethoven became the incarnation of romantic genius. But in spite of his notoriety, he did not have the same celebrity as Byron. It is true that Beethoven had immense prestige attached to his name after the middle of the century, but this renown could not have been guessed at given his early career. Certainly, he had nothing of the cursed artist about him. His career in Vienna was dotted with brilliant successes. He was soon recognized as one of the great composers of his time, if not the greatest, and benefited from the support of important figures in the imperial court, who had a profound admiration for him and assured his financial security. But his growing reputation remained within the circle of musical patrons. His talent was challenged by a part of the Viennese public who found his works too difficult, too arduous, too far from those forms capable of pleasing a larger audience. Beethoven himself made very few concessions: “I do not write for the crowd,” he exclaimed, dismayed and furious after the failure of his opera Fidelio. He could allow himself this kind of intransigence because of the loyal support of his patrons. Contrary to the legend, Beethoven's career unfolded for the most part in the traditional context of the imperial court and Viennese salons.46

It was not until 1814 that Beethoven acquired both international celebrity and real popularity in Austria, having composed works to celebrate the military losses of Napoleon. The November 1814 concert on the occasion of the Vienna Congress assured his reputation as a great patriotic composer. This celebrity, however, was not as long-lasting as one might imagine. A replay of the concert a few days later ended in a commercial failure. During the years that followed, Beethoven lost part of his court support, isolating himself more and more because of his deafness, but also because of his creative evolution. Beethoven kept his enthusiastic admirers and received commissions from England, Germany, and even the United States, but these came from groups of musicians and music lovers. It was above all in Vienna, and in some German cities, that his death in 1827 was an event. In Paris, at that time, he was seldom heard.

The case of Beethoven makes it possible to distinguish between the system of celebrity and the effects of reputation, even when exceptional, on an artist. There is no doubt that Beethoven obtained the unconditional support of the Viennese elite and European music lovers, who profoundly admired him early on, beginning in the mid-1790s, and even more clearly during his great creative period in the 1800s. With his triumphs in 1814, his reputation was better established but rested on an heroic and patriotic style that had made him successful but from which he tried to move away. Essentially, it was after his death that a real fascination with his work developed.47

While alive, Beethoven remained on the edge of celebrity, less popular, for example, than Rossini. Stendhal wrote in 1824, the same year as the creation of the Ninth Symphony: “Napoleon is dead; but a new conqueror has already shown himself to the world; and from Moscow to Naples, from London to Vienna, from Paris to Calcutta, his name is constantly on every tongue.” He was talking about Rossini, then just thirty-two, whose success in Naples and Vienna and his triumphal tours of Paris and London occupied the attention of the public, as well as the press, and to whom Stendhal had already devoted a biography.48 However, posthumous excitement about Beethoven's genius among romantic musicians continued to grow. This helped create a new relationship to musicians and to music, on which the extraordinary popularity of Franz Liszt would be based.

Liszt, of whom it was said that his face, when he died, was the most well known in Europe,49 greatly contributed to the cult of Beethoven. Having benefited from a precocious celebrity starting with his first concerts as a child prodigy in Paris in 1823–4, ten years later he was the darling of the Parisian public, which was fascinated by his virtuosity, by the anecdotes of his affair with Marie d'Agoult, and by his provocative writings, borrowed from Saint-Simonism, in which he demanded the social elevation of the musician and pleaded for a form of spiritual music. As the adored pianist of polite society, he was welcomed into the best salons in the Saint-Germain quarter, where he had no fear of denouncing the “subaltern” role occupied by musicians (“Is the artist anything more than a salon entertainer?” he asked), of mocking the lack of musical culture in his admirers, or of appealing for a new kind of popular music, inspired, fraternal, and universal. “Vienna, oh, Vienna the hour is near for deliverance, when the poet and the musician will no longer say ‘the public,’ but ‘the PEOPLE and GOD.’ ”50 Liszt intelligently and successfully occupied a unique and very visible position in Parisian cultural life, half-way between the traditional figure of the salon pianist and that of the romantic artist, foreshadowing a new era.51

The summit of celebrity for Liszt came with his vast European tour beginning in 1838, which took the pianist from Vienna to Berlin and then to London and Paris, sometimes arousing extreme reactions in the public.52 Such reactions also provoked criticism and mockery. In Berlin in 1842, the fervor surrounding his concerts reached an unprecedented intensity that fascinated critics and journalists. Liszt's performances created a new level of collective excitement. Vocabulary used to describe madness was commonplace as everyone tried to understand this recent form of pathology.53 Cartoons showed Liszt's audiences being taken directly to the madhouse after a recital. Liberals saw in the musician's popularity the consequences of insufficient political freedom, as though public passions in Berlin were focused on this objective. Conservatives deplored such unrestrained behavior, which seemed excessive and inappropriate. They were alarmed by the reactions of women as though infatuation with the virtuoso came from sexual excitement. Overall, what predominated was a mixture of surprise, worry, and amusement. There were multiple repercussions from Liszt's success. Not only did spectators turn themselves into a spectacle, but commentaries provoked by these new reactions focused on the public's interest in Liszt's celebrity. Although the price of tickets meant that only the Berlin bourgeoisie and polite society could attend the concerts, curiosity aroused by Liszt's presence in cities, through newspaper stories, café conversations, and a profusion of cartoons, attracted the interest of a much larger population: Liszt was “talked about with delight in the palaces of the great as well as the cottages of poverty,” wrote Gustav Nicolaï in a local newspaper.54

How could such celebrity be accounted for? First of all, Liszt's career path can be explained by the new conditions surrounding musical life. While he did remain dependent on aristocratic patronage in the first decades of his career, he benefited from the explosion of public concerts and revolutionary piano techniques. Whether he was performing his own compositions or those of others, from 1835 onward, Liszt created a model for the individual recital, where the musician was alone on stage facing his public. Even Paganini, the great virtuoso whose concerts so impressed Liszt early on, played with an orchestra. It was Liszt who invented the solo recital. At the same time, the bourgeoisie privileged the piano and imposed piano education on all young girls from good families, creating an even greater interest in the instrument and an increased curiosity in virtuosos like Liszt, but also Sigismund Thalberg or Henri Herz.55

Instrument virtuosity from this point on surpassed that of an aesthetic experience and became a performance resembling a sporting event. This aspect ended in duels, like that between Liszt and Thalberg, a rivalry fed by a series of successive challenges and provocative statements. The comparison with boxers, their rivalries and their matches, might seem grossly anachronistic, but it came spontaneously to mind at the time, in particular in England, where, since the end of the eighteenth century, boxing matches had become a popular spectacle assuring the celebrity of men like Daniel Mendoza, a vertitable entrepreneur when it came to his own sporting fame.56 Even when music emancipated itself from this type of rivalry and the artist came face-to-face with his public, virtuosity remained a performance worth as much by the surprise it caused as by the emotion it provoked. People came to see a man perform seemingly impossible physical and technical feats. Comparisons of Liszt to Bonaparte were often made, Liszt appearing to be an audacious and conquering personality, readily adopting a martial posture and displaying his taste for astounding feats.57 He threw out challenges such as playing the finale of Berlioz's Symphonie fantastique on the piano, causing an “indescribable delirium” in the public when confronted with this unlikely utilization of the instrument.58 In March 1837, he surprised everyone by announcing a solo piano recital at the Opera, on a Sunday. The press could not get over it: “Playing piano at the Opera! Transporting the thin, sickly sounds of a solo instrument into this immense hall where the echoes of the Huguenots still resounded, a hall accustomed to every dramatic emotion … and this, on a Sunday, in front of a mixed, uncultivated crowd! What a spirited undertaking!”59

Reference to the audience as “mixed” and “uncultivated” was decisive. In order to seduce his new public, Liszt did not propose original or difficult compositions; instead, he played improvised and whimsical airs from well-known operas. Adding to the public fascination with these performances was familiarity with popular melodies. Word about this new kind of music spread through the use of publicity, or rather, as one said in the nineteenth century, advertisements. Liszt was one of the first musicians, after Paganini, to use the services of an impresario, Gaetano Belloni, who was in charge of organizing his tours, inserting publicity announcements and laudatory reviews in newspapers, but also watching over the publication of engraved portraits of the composer.60 Liszt himself possessed a cunning sense of self-promotion: he wrote short autobiographies in German and French, which piqued the interest of the public, never hesitating to be provocative in press articles, and published letters in newspapers that he wrote to friends and in which he recounted the welcome he was given at concerts. He especially liked to show off his charitable temperament, organizing concerts for humanitarian causes, for example after the floods in Pest, and taking care to make his selfless nature known.

The result of this intense music and marketing enterprise was the existence of a strange new public figure, a sentimental musician nurturing a dream of spiritual music; a showman capable of attracting crowds; and an ordinary man with a fondness for genteel and aristocratic poses. It was Liszt, better than any other musician of his time, who knew how to maintain this perfect ambiguity, that of the “subversive virtuoso,” both hostile to elites and fascinated by their model of gentility, cultivating with his public a sentimental closeness and a rather haughty distance. And since Rousseau and Byron, two men dear to Liszt, had this type of ambiguity not become one of the powerful resources of celebrity?

This figure of the sentimental and virtuoso musician, pulling all the publicity strings, found an acerbic observer in the person of Henrich Heine, a German writer living in Paris, passionate about music, lucid and readily sarcastic. When Liszt returned triumphant to Paris in 1844, Heine, in a lengthy column that was both funny and cruel, wrote about the success of the “great agitator,” “our Franz Liszt,” “doctor in philosophy and sixteenth notes,” “a modern Homer that Germany, Hungary, and France each claim as their own, while only seven little provincial towns” claimed to be the birthplace of The Illiad's cantor, or the “new Attila, God's scourge on all the Érard pianos.” After this succession of comic comparisons, he invokes the “incredible furor” that had electrified Parisian society, the “hysterical crowds” of women spectators and their “frenetic acclamations.” He then pretends to be astonished that the Parisian public, which he thought was more blasé than the German, should be caught up in such passion for a pianist:

What a crazy thing! I said to myself, these Parisians who had seen Napoleon, the great Napoleon, who had to engage in battle after battle in order to keep them focused on him and to get their approval, these same Parisians shower our Franz Liszt with acclamations! And what acclamations! A real frenzy, like there has never been before in the annals of madness.

He continues in a medical vein, suggesting that such collective enthusiasm was due to “a pathology rather than an aesthetic.” He then abandons this convenient criticism and falls back on a more prosaic explanation: the real genius of Liszt lay in his ability to “organize his success, or rather to produce it.”

Heine then gives free rein to a thorough critique of the publicity system of celebrity. He spared nothing, including the philanthropic reputation that Liszt so willingly put to good use. If Heine was to be believed, Liszt's success, it seems, was a fiction, supported by new commercial strategies: it was the role of Belloni, “the general intendant of his celebrity,” to buy the laurels, the bouquets of flowers, “laudatory poems and other ovation expenses.” It is clear that celebrity at this point entered a period of mistrust. It was a matter not only of criticizing the excessive enthusiasm of the public, but even of doubting the reality of the triumphal shows. And if it was all just a pretense, smoke and mirrors?61 At this point, Heine, who detested the society of the spectacle and the “star-system,” as moralists nowadays do, went even further, proposing a general criticism of celebrity earned by virtuosos meant less to denounce this celebrity than to bring it into balance: “Let us not look too closely at the homage that is earned by celebrity virtuosos. After all, their vain celebrity does not last long.” And he wrote the same thing in a more unexpected and imagistic way: “The ephemeral renown of the virtuoso fades to nothing, without leaving a trace or any resonance, like the whinnying of a camel crossing desert sands.”62

Liszt himself was not unaware of the limits of “sterile celebrity” and “egoistical joys,” which he spoke about in an article published on the death of Paganini, contrasting him with real art.63 Perhaps he wanted to avoid the sad fate that Heine promised him, that of an old virtuoso becoming anonymous once more, dwelling on the memory of a vanished celebrity. Certainly he had been torn for a long time between the headiness of success and the desire to produce authentic work. In 1847, at the height of his notoriety, he decided to end his career as a concert virtuoso and accepted a position in Weimar, dedicating himself to composing. This choice, accompanied by a return to the Catholic faith, leads one to think that his declarations of his mistrust of celebrity were more sincere than one might have believed. He had written almost ten years earlier, at the time of a triumphal tour in Italy:

So, I confess I have often pitied the petty triumphs of satisfied vanity while bitterly protesting against the excitement with which I have seen works without conscience or portent welcomed; just so, I have wept over what others called my success, when it was clear to me that the crowd rushes to an artist to ask him for some passing amusement and not instruction about noble feelings. I felt as wounded by the praise as by the critics, refusing to recognize such frivolous judges.64

Instead of finding these words suspect, seeing in them only the coquettishness of a star, why not allow Liszt some credit and admit that he, like Rousseau, Byron, or Siddons, had a complex and ambivalent relationship to his own celebrity? Celebrity was not an entirely legitimate form of recognition, because immediate public enthusiasm broke the balance of recognition by one's peers. It was impure; it owed too much to commercialization, to the expedients of advertising and to the subterfuges of what was not yet called the marketing culture. The virtuoso was the embodiment of all this. Appearing first in the eighteenth century, he belonged as much to the world of spectacle as to that of art; he seduced through his performances more than through his art; he abdicated his artistic destiny, which implied slow maturation, choosing instead immediate satisfaction from a public which expected to be both astonished by his musical mastery and comforted in its taste. The virtuoso put himself on stage and became the center of a spectacle, making himself the entrepreneur of his own public persona.65 He rejoiced in seeing his vanity flattered, but could remain conscious of the vanity of his success, because he knew, better than anyone, the artificiality of acclamation, that celebrity was only a selling point. In his most ironic mode, Liszt made fun of mediocre concerts given by “average, dull musicians who, in spite of two hundred posters, green, yellow, red, or blue, tirelessly advertising this celebrity to the two hundred corners of Paris, were condemned, nonetheless to remain anonymous forever.”66 Very early in his career, he felt a distrust of public success, although he would benefit from it in the following years. His relationship to music came from a sensibility torn by desire for immediate recognition that sustained his taste for success and a feeling of artistic independence where real recognition implied keeping a distance from the demands of the public.

Celebrity in America

Liszt's European career showed that the geography of celebrity had changed. His success, far from being limited to Paris or Vienna, took him to Zagreb and Pest, to Berlin and London. Other virtuosos traveled across the Atlantic, like the French pianist Henri Herz, the Austrian dancer Fanny Elssler, whose American tour was a great success from 1840 to 1842, or the Norwegian violinist Ole Bull, whom Heine called “the Lafayette of the puff,” because “in terms of advertisements [he] was the hero of two worlds.”67 In fact, between 1830 and 1840, the celebrity system began to show a definite growth in the United States, becoming a prominent force in popular American culture of the twentieth century and later. As in Europe, it was first of all in the literary domain that the rapid urban growth occurred; an increase in print shops and new commercial techniques made their effects felt. The writer Nathaniel Parker Willis very much embodied this development. Somewhat forgotten today, he was a major figure in American cultural life in the middle of the century. He made himself known early by his recounting of a trip to Europe, and by vivid and funny stories about figures of New York high society. Both writer and journalist, he became the most celebrated and best-paid author of his time, managing several newspapers and, in particular, founding the Home Journal in 1846, in which he set the trend for cultural life on the East Coast. Both a celebrated author, an editor – he unfailingly supported the career of Edgar Allan Poe – and an arbiter of fashion, he illustrated social and cultural changes that accompanied urban growth in New York, the population going from 240,000 inhabitants to 1.2 million in thirty years (1830–60). Willis became a well-known public figure, but an extremely controversial one, often ridiculed for his effeminate and affected character. As one journalist wrote about him, “No man has lived more constantly in the public eye for the last twenty years than Willis, and no American writer has received more applause from his friends and more censure from his enemies.”68

Willis had also been witness to the most profound transformation in public spectacles, especially in Europe, where their commercial development had been much faster. In contrast with the Old World, the United States did not have a tradition of court spectacle and aristocratic patronage, so the modern show-business economy could expand almost unfettered, driven by risk-taking entrepreneurs, and in particular the impressive Phineas Taylor Barnum. He has remained famous for his gigantic traveling circus, modestly called The Greatest Show on Earth, for his exhibition of monstrous humans, and for his collection of objects in the Barnum American Museum, making him a major figure in popular American culture, symbol of the wily and seductive entrepreneur, producer of ambitious spectacles. He began his career with less brilliant shows, notably exhibiting Joice Heth, an old black woman who claimed to be a hundred and sixty years old and the former wet nurse of George Washington. Then it was the turn of Tom Thumb, a child dwarf whom he made into a veritable star at the beginning of the 1840s.

Spectacles made up of human curiosities, notably racial, were not completely new. In 1796, citizens of Philadelphia had already seen a “great curiosity,” a black man who had become almost completely white, exhibited daily in a tavern for half a shilling. The man, Henry Moss, was for a while a celebrity with a very ambivalent status, attracting crowds of curious people as well as scientists and philosophers.69 Barnum, however, gave his productions a new dimension, adapting them to the latest spectacular forms of media, and starting a period of “Freak Shows.”70 But he wanted respectability. Once he was an impresario, he organized American tours for European celebrities, giving an almost business-like dimension to the art of the puff piece, which consisted of publishing ecstatic press notices about artistes in order to arouse public curiosity.71

His greatest accomplishment was to bring the Swedish opera singer Jenny Lind to the United States, who was already very popular in England and throughout northern Europe. At twenty-nine, she decided to renounce the opera and tour America doing recitals, a period that lasted two years and ended in triumph. Her arrival in New York and then in Boston in September 1850 was welcomed with enthusiasm by the press. On September 2, 1850, the New York Tribune reported that between thirty and forty thousand New Yorkers rushed onto the quays to see the boat that carried the singer, resulting in several injuries.72 The crowds hurried to the concerts, and newspapers kept publishing articles about the singer and about the frenzy that overtook the public, what the Boston Independent described as “Lindomania” during the singer's visit to the city.

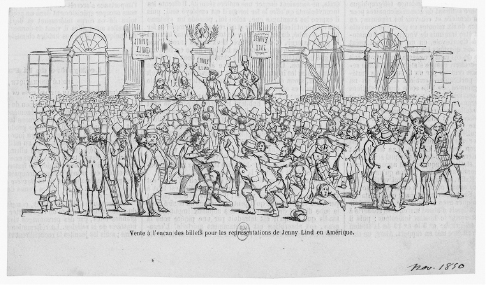

This triumphal tour by the “Swedish nightingale” marked the entrance of celebrity culture into the United States. Barnum was the great director; first he tried out publicity methods like bidding sales for concert seats, which encouraged cheating and a rise in prices, at the same time assuring the anticipated publicity for the show (Fig. 16). Lind was not only a singer; she had become a product. Barnum, needing to amortize the considerable sums he had invested in the tour, did not hesitate to showcase the public person of Jenny Lind as the ideal young woman, virtuous and meritorious, poor, puritan, and philanthropic, her success owing everything to hard work – a veritable incarnation, in short, of American values. Several biographies of Lind were published the year she arrived in America, one of them written by Willis himself, and all the newspapers picked up on her most remarkable traits, even those that had been invented for the articles. Curiosity about the person of Lind was such that her vocal talent sometime seemed of secondary interest.73 Barnum went so far as to claim, much later, that her success owed nothing at all to her voice and everything to the publicity that he had orchestrated. These statements, written after the rupture of their agreement, are no doubt exaggerated, but they show a strong awareness of the autonomous system of celebrity.

The most striking aspect of Lind's success, one that historians have now clearly demonstrated, was the creation of a public persona, an incarnation of the natural, the authentic, and the selfless. However, Lind was not an innocent whose image supposedly was manipulated by Barnum. She was a smart woman who did not hesitate to question her contract with the entrepreneur when she found it profitable to do so. The construction of her public persona, that of the “Swedish Nightingale,” built around simplicity and modesty, was a collective work in which she very much took part, along with Barnum and a large number of journalists who enthusiastically intoned hymns of glory to her. Some journalists, it is true, sensed something odd in the flagrant contrast between, on the one hand, the enormous promotional machinery, the outlay of press articles accompanying Lind's every change of venue, the profusion of products bearing her name and, on the other, the constant praise of her simplicity and naturalness, which led certain admirers to claim that she sang purely by instinct, out of pleasure, paying no attention to the audience. “A lot of artifice is necessary to appear so artless,” one critic ironically remarked, but the discreet voice of skeptics was drowned out by the collective enthusiasm.

In the end, Lind gave almost a hundred concerts in two years, crossing the United States, north to south, from Boston to New Orleans, even giving a recital in Cuba, before returning to New York, where she once again had great success. The success of this tour was measured first of all in commercial terms, Lind and Barnum each taking home nearly two hundred thousand dollars.74 But it was much more than that: it signaled a cultural change. Everywhere, the streets, public squares, and theaters were named after her, all the way to San Francisco, where the Jenny Lind Theater opened in 1850 above a saloon.75 Numerous articles in the press accompanied this long tour and testified to the impact Lind made during her stay, but there was also the desire by the American public to be seen as equal to the displays of enthusiasm by European crowds. For Willis, as for so many others, Lind's success indicated the cultural level that the United States had attained with the emergence of a middle class, one capable of appreciating European culture. Once again, the rapid and spectacular effects of celebrity brought with it a flood of commentaries speculating about the nature of the phenomenon and its significance.

Who was Lind's public? First of all, contemporaries such as Barnum emphasized the varied and egalitarian nature of her audiences, where the common people supposedly mingled with the elite. Actually, the price of tickets separated the elite from tradesmen and rural laborers, and it seemed that some of the well-heeled elites from polite society in New York or Philadelphia kept their distance from a phenomenon which appeared to them lacking in dignity. On the other hand, the urban middle class, then in full expansion, was wildly enthusiastic. Whereas opera music was becoming an entertainment reserved for the elite, Lind offered them the great operatic airs from Bellini to Rossini, ending her tours by singing popular American songs such as “Home Sweet Home.” Given the way the press presented her, she incarnated the bourgeois ideal of femininity: modest, unaffected, and a philanthropist. Her celebrity, however, grew far beyond merely the public who attended her concerts, through the publicity sent out about her. In the Bowery, one of the working-class areas of New York, one could find cheap products sold with the name of Lind on them, in the same way luxury products associated with the singer were found in expensive boutiques. Lind's celebrity rose above the division in American social classes. While not being as universal as Barnum claimed, she paralleled the emergence of a commercial culture, aimed not at the distinguished elites nor at the traditional working class but created principally for the middle class, although capable of reaching a much larger market given the media reverberations of the stars who made up the celebrity culture.