The first requisite is information. The air service and the cavalry must discover the direction of march and strength of the hostile columns, and until the former is known, the force should not be deployed, even when the enemy’s line of advance may be foreseen.

Field Service Regulations, Part I: Operations (1909)

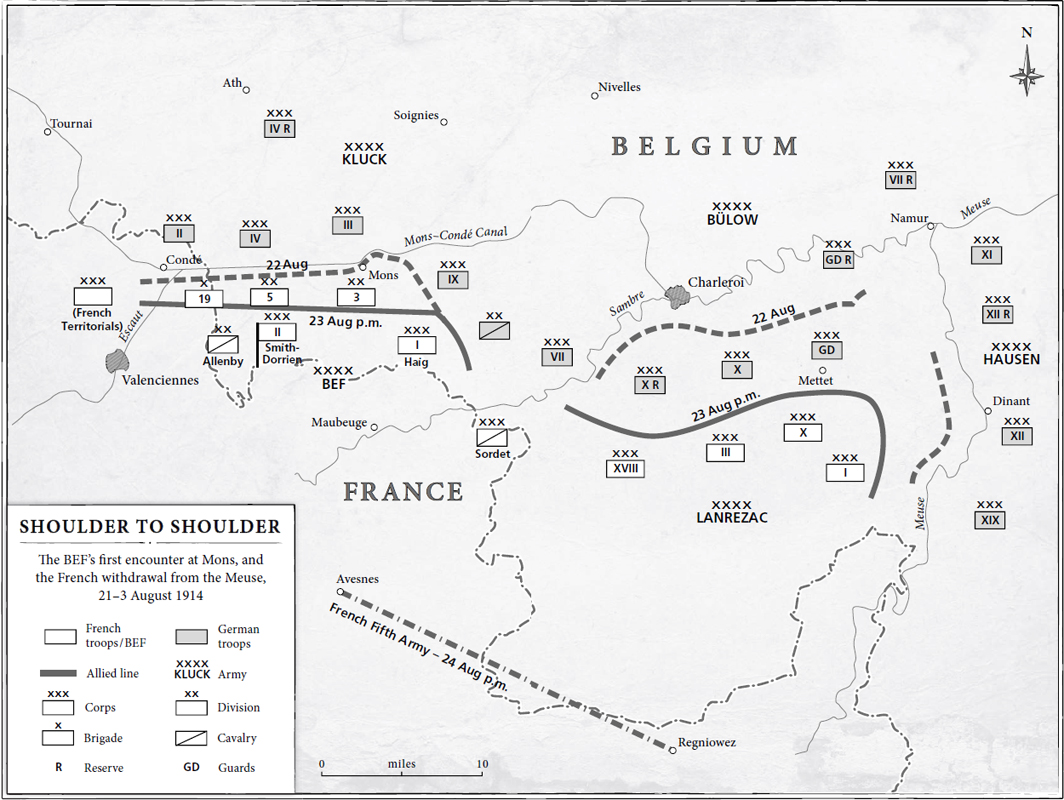

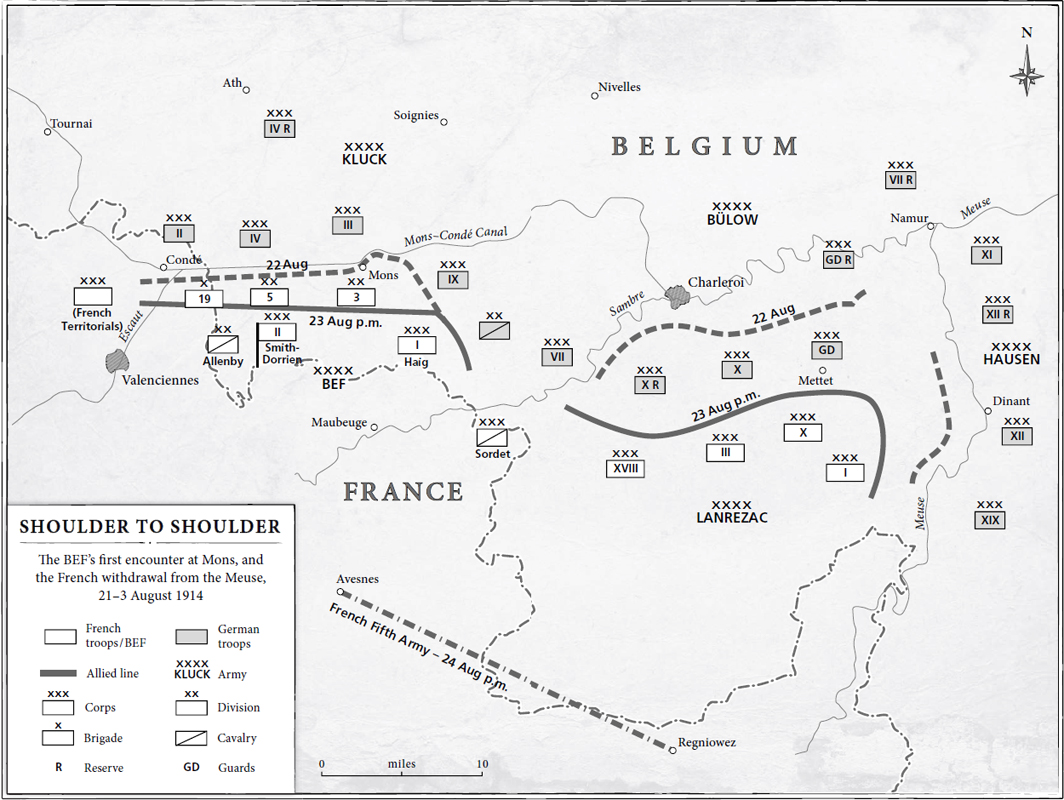

Early in the afternoon of Thursday, 20 August, GHQ issued Operation Order No. 5, launching the BEF’s great forward movement north of the Sambre. Signed by Lieutenant-General Sir Archibald Murray, the chief of staff, it contained in detailed appendices the ‘march tables’ for the next three days – the Cavalry Division leading, followed by II Corps under the temporary command of Major-General Sir Charles Fergusson (GOC 5th Division), then Haig’s I Corps – in all some 80,000 men.fn1 But whereas operation orders usually begin with the ‘situation’ – a summary of all that is known of the enemy and friendly forces – because the mission and its execution follow logically from those factors (and generations of officers have been taught to mistrust any orders that do not begin thus), Operation Order No. 5 began with the worrying notice that ‘Information regarding the enemy and allied troops will be communicated separately.’

Even worse, it never was, for events would overtake GHQ.

And so the primary stipulation of Field Service Regulations, the British army’s painstakingly written new handbook of war, that ‘The first requisite is information’, was to be set aside in its first real outing in the field. Such is the gulf, sometimes, between theory and application; but so profound was this departure from what was after all a fundamental precept of war, and at the very outset of operations, that success was now more likely to be a matter of chance than calculation. Indeed, this stark failure by the general staffs of both GQG and GHQ set the BEF on a calamitous course from which it never truly recovered. Not only was the collection of intelligence dilatory, its interpretation was wishful. The logical process of the ‘intelligence cycle’ – a modern term, but the process was understood well enough at the time – provides information on which the commander decides his course of action. GQG, and in their wake GHQ, turned this on its head: having decided their course of action – Plan XVII – they interpreted the intelligence to confirm the correctness of the decision. That which tended to suggest the decision was wrong was effectively ignored, dismissed as inaccurate – ‘it could not be true’ – or distorted to fit the original assumption. The refusal in peacetime to admit the possibility that the German main effort would be on the right was bad enough; that it continued for so long once battle commenced is one of the great military failures of August 1914. The battle that was to follow Operation Order No. 5 – Mons – should never have taken place. It was at best a ‘hasty defence’ – never a satisfactory thing – and to all intents and purposes a ‘meeting engagement’, and such battles are the results of a failure one way or another to gain or correctly interpret intelligence.fn2 Ironically, the battle of Waterloo, which had been fought a day’s march to the north-east, had been preceded by a desperate meeting engagement – at Quatre Bras. And before that occasion, famously at the duchess of Richmond’s ball, the duke of Wellington had at least had the good grace to say that ‘Napoleon has hoodwinked me, by God!’ By contrast, on the evening of 21 August, on receiving a report by the Cavalry Division of a much more extensive threat to the BEF than had been thought, Henry Wilson would blithely send this reply: ‘The information which you have acquired and conveyed to the C-in-C appears to be somewhat exaggerated.’fn3

Sadly, the reaction of the divisional commander, Major-General Edmund Allenby – ‘the Bull’ – is not recorded.

Fortunately, however, the army’s newest instrument of war, the aeroplane, would soon begin to penetrate this cloud of self-delusion – once it had been able to penetrate the actual clouds that shrouded the approach of ‘Old von Kluck and all his b— army’. As GHQ were putting the finishing touches to the somewhat sketchy Operation Order No. 5, on 20 August, the RFC was beginning its second day of operations, this time with observers – but only two aircraft. Quite why only two is unclear even today: if the weather was good enough for two to fly, it was good enough for many more, and there were now nearly sixty machines sitting at Maubeuge. This was a moment when intelligence was of the absolute essence, when there was an acknowledged lack of it – as witness the operation order – and when there was no other direct way of gaining it. But GHQ were not expecting the Germans to be doing anything other than ‘ranging with uhlans’ west of the Meuse and turning, perhaps, east of it to meet the threatened attack by the French 4th and 3rd Armies – which the French themselves would surely be observing. Why, therefore, ask the RFC to do much more than take a look to see how far the ‘ranging uhlans’ had got?fn4 The first aircraft on 20 August reconnoitred as far as Louvain and the outskirts of Brussels, seeing a force of all arms moving south-west of the capital, and another south-east into Wavre. A second patrol, south-west of Brussels (in a triangle Nivelles–Hal–Enghien), saw no sign of troops, and all the bridges intact. All this was useful negative information; but what would have been really helpful was to know just where were the ‘as many as fifteen army corps’ that Joffre’s Instruction Particulière of 18 August had conceded might constitute the German right wing. To commit to any large-scale movement without knowing was courting trouble.

It was foggy next morning, Friday the twenty-first, as the men of the BEF left their billets and bivouacs in the pleasant farms and orchards and the industrious villages of Hainault to strike out north for the Belgian border. In the afternoon it rained, the mist persisting, and the three reconnaissance flights that eventually managed to take off reported that the country immediately in front of the BEF was quiet, though just south of Nivelles there was a large body of cavalry with guns and infantry (later identified as the German 9th Cavalry Division), and another body of infantry moving south on Charleroi, leaving several villages ablaze. It is tempting to think that the RFC’s Beta airship, left behind at Farnborough, would have been invaluable, and perhaps even more use than aeroplanes, at this stage – or for that matter, a regiment of armoured (or even unarmoured) cars. Field Service Regulations (FSR), although originally issued in 1909, a year before the first aeroplane flew on army manoeuvres, and when the army’s airships were still experimental, was remarkably prescient in recognizing the importance of air reconnaissance: ‘The air service and the cavalry must discover the direction of march and strength of the hostile columns.’ And the amendments to FSR issued in October 1914 were still strong on the role of airships, even without seeing them in France: ‘Airships can, by their power of remaining motionless in the air, keep a large tract of country under observation.’ The weather was poor (the Zeppelins had been kept in their hangars, after all), but the problem locally was visibility, not wind – not impossible conditions for the Beta.fn5

But while bad weather had grounded the RFC in the morning, it had not slowed the advance of Allenby’s Cavalry Division, which entered Mons towards midday to a warm welcome. At once the division’s intelligence officer, George de Symons Barrow, a somewhat ‘passed over’ Indian cavalry lieutenant-colonel whom Allenby had scooped up in London (where Barrow was home on leave) to fill the unofficial post in his headquarters, went to the telephone exchange at Mons station and

sat all day and far into the night ringing up all possible and impossible places in Belgium not known yet to be in German hands … Replies took the following forms: ‘No sign of enemy here, but rumours they are in A—.’ ‘Germans are five miles distant on road to B—.’ ‘Have just received message from C— that enemy close to town; we are closing down.’ A German voice or failure to get contact told that the enemy had already arrived.fn6

The intelligence was admittedly hearsay or presumption, but it was on such a scale that it could not be ignored – or should not have been; and yet Henry Wilson dismissed it as ‘somewhat exaggerated’. In truth, it hardly needed the Cavalry Division to ride to Mons to telephone round Belgium: GHQ’s intelligence section could have done the same from Le Cateau, and the RFC could then at least have been tasked with verifying the information gleaned. But at this stage there was still innate trust in GQG’s intelligence, sparse though that was.fn7

However, the Cavalry Division was at least able to make contact with the French Cavalry Corps. The GSO2 (general staff officer 2nd grade – in effect the division’s deputy chief of staff), Lieutenant-Colonel Archibald ‘Sally’ Home, was sent to Fontaine l’Évêque, just to the west of Charleroi, where he found General Sordet ‘very polite and punctilious [but the] horses very tired, they had been having a good doing’. Unlike British cavalry, who dismounted to lead their horses when they came to the walk, the French practically never did so, and their horses frequently stank, so bad were the saddle sores. In truth the corps had been run ragged for the past fortnight and had lost a sixth of their strength before firing a single shot. In any case, they were going to be no good to the BEF at Charleroi: they were meant to be covering the left, open, flank, not the right (the right flank was, GQG assured them, covered by the solid mass of Lanrezac’s 1st Army). So Sordet would somehow have to cross the BEF’s entire front – not the most secure of manoeuvres.

Fortunately, late that Friday afternoon General Sir Horace Smith-Dorrien had at last arrived at II Corps headquarters at Bavai.fn8 He had only received the telegram appointing him to command on the Tuesday morning, with an immediate summons to London to see Kitchener. There is no record of the interview that day, but in Smith-Dorrien’s memoirs are the somewhat Delphic remarks:

Lord Kitchener’s first words to me, when I entered his room at the War Office that afternoon, expressed grave doubt as to whether he was wise in selecting me to succeed Grierson, since the C.-in-C. in France had asked that General Sir Herbert Plumer should be selected to fill the appointment. However, after thinking the matter over, he adhered to his decision to send me.fn9

In his rebuttal of Sir John French’s memoir 1914 (published in 1919), which he wrote in 1919–20 but was allowed only to circulate privately because he was still in uniform, Smith-Dorrien states that Kitchener had said that the CIGS (Douglas) had ‘just told him’ that the appointment would be putting him in ‘an impossible position’ owing to the ‘great jealousy and personal animus’ shown to him by Sir John French over many years, and which was ‘well known to the Army Council’. Whether that meant Kitchener had made the appointment before receiving Sir John French’s request for Plumer is unclear, but he had nevertheless decided not to alter his choice, and this was a statement of a lack of confidence in someone. But the secretary of state – who was in any case acting outside his political authority (and it would have been better had French not asked for Plumer in his letter, thereby suggesting that it was indeed a matter within his authority) – would hardly have delayed Smith-Dorrien’s departure unless he had something substantial to say. He certainly mistrusted Henry Wilson, or at least Wilson’s view of the situation. On 7 August – according to Wilson’s diary – there had even been strong words between the two. Since the twelfth, when the Times military correspondent, Repington, had published a remarkable map showing the disposition of German corps in France and Belgium, Kitchener had grown ever more certain that Wilson’s appreciation (which meant GQG’s, essentially) was flawed; at the very least, therefore, he would have warned Smith-Dorrien of Wilson’s dangerous over-optimism, as well as his undue influence over Sir John French. To speculate further would be vain; in any case, if Kitchener did indeed speak in these terms to Smith-Dorrien, he was, by inference, signalling his lack of confidence in the commander-in-chief.fn10

On 21 August, his staff having briefed him on the move forward, the new corps commander motored back to see Sir John French at Le Cateau: ‘He received me pleasantly, and explained the general situation as far as he could, for the fog of war was peculiarly dense at that time,’ he wrote in Memories of Forty Years’ Service. In truth, ‘pleasantly’ was almost certainly a case of decorum, French being still alive at the time of writing. In the (earlier) rebuttal he says: ‘I was not very cordially received.’

After receiving the new commander of II Corps with indeterminate pleasantness, French told him that they were to move next day to the general line of the Mons–Condé canal, I Corps on the right, II Corps on the left, ‘but that it was only to be a preliminary step to a further move forward which would take the form of a slight right-wheel into Belgium, the British Army forming the outer flank, pivoting on the French 5th Army.’fn11

Smith-Dorrien almost failed to make it across the start line, however, for soon after leaving Le Cateau, as daylight was beginning to fade, his car ran into a skirmish, ‘the road blocked, bullets flying, and the sound of firing,’ he relates, with an artillery battery ‘in considerable confusion held up by sharpshooters across the road’. It turned out to be, in the modern vernacular, ‘blue on blue’ – mistaken identity.fn12 The battery had been challenged by French Territorials; not understanding what they were meant to do, the gunners had tried to push on, so the French had opened fire, killing one and wounding two more – a miserable job for the battery commander to have to explain in the letter to the next-of-kin.

‘This was a bad beginning,’ reckoned a tired Smith-Dorrien, who seems to have taken matters in hand himself (which must have been an interesting experience for the French as well as the gunners – a four-star general reverting to subaltern): ‘a brief parley arranged matters and I got to my head-quarters at 11 p.m., approved of the orders for the move next morning [the 22nd], and turned in.’

That night a worried Spears came to GHQ after a hazardous drive on roads full of horse transport, many of the drivers fast asleep. He told Henry Wilson that he feared General Lanrezac was about to abandon the idea of offensive action, in which case the BEF would be left in a perilous position if they continued to advance. Wilson could not believe it (another case of cavalry nerves, no doubt – Spears, ‘Monsieur Beaucaire’, was an 8th Hussar), but agreed that it would be a good thing for Sir John French and Lanrezac to meet the following morning. When Spears got back to 5th Army headquarters he learned that the French II and X Corps had been attacked that afternoon on the Sambre, to the east of Charleroi.fn13

Next day, the twenty-second, the clouds began to lift – literally and metaphorically. The RFC quickly got away twelve patrols and were soon reporting large numbers of troops approaching on the BEF’s line of advance. The first plane to return, soon after eleven, had landed at Beaumont, about 12 miles east of Maubeuge, for petrol, to be told that French cavalry had encountered German infantry north of the Sambre canal the previous afternoon, and had had to fall back – extraordinary news indeed, for there had been no word of it from the 5th Army. The next to return, just before midday, carried the first casualty to enemy fire, an observer, Sergeant-Major David Jillings. His plane had come under heavy rifle fire south-east of Lessines, not 20 miles north of Mons, and then, passing over a cavalry regiment just south-west of Ghislenghien, had met rifle and machine-gun fire. Indeed, the plane had drawn rifle fire all the way back to Ath, where Jillings had been wounded in the leg. By the end of the month a leg wound, even to an aviator, would not have rated a mention; but on 22 August it was a sort of signal that the BEF – the Royal Flying Corps, at least – had definitively passed from a peace to a war footing. And passed with some style: Jillings had almost certainly brought down a German Albatross by rifle fire (possibly with a single shot) near Lessines. He was awarded the MC in 1915 and later commissioned.

It would have been some consolation to GHQ had they known that the Germans had been as much in the dark as they were, at least about who was in front of them. Kluck actually learned of the presence of British troops not from a German plane but from an RFC one: ‘It was only on the 22nd of August that an English cavalry squadron was heard of at Casteau, six miles north-east of Mons, and an aeroplane of the English fifth flying squadron was shot down that had gone up from Maubeuge. The presence of the English in front was thus established, although nothing as regards their strength.’fn14

The cavalry at Casteau was C Squadron of the 4th (Royal Irish) Dragoon Guards commanded by Major Tom Bridges who, by one of those strange coincidences of war, had recently been the military attaché in Brussels. Before the 2nd Cavalry Brigade had left Tidworth, its commander, Brigadier-General Henry De Beauvoir De Lisle, had gathered his officers together for a pep talk during which he asked Bridges his views on the strength of the Belgian fortresses. The former attaché gave a very accurate estimate of the holding power of Liège but wholly over-estimated that of Namur.fn15 And then De Lisle asked how long he believed the war would last, to which Bridges replied ‘six months’. De Lisle thought otherwise: ‘Make no mistake, gentlemen; we are in for a long and bitter war.’ But he then rallied them with the promise that the first officer to kill a German with the new-pattern (1912) cavalry sword would be recommended for the DSO.fn16

And by another coincidence, it was Bridges’ second-in-command, Captain Charles Hornby, who would gain that DSO. C Squadron had been pushed forward on the afternoon of the twenty-first to try to gain contact, but they met no Germans, learning only from refugees that ‘uhlans’ had bivouacked about 15 miles north.fn17 It was yet another blisteringly hot day, the cobbled roads ‘a proper bugger’, recalled Farrier Arthur Newton of the 5th Lancers: ‘I seemed to spend my whole time shoeing horses … It would have been better if we had ridden across country, but the orders were that we weren’t to damage standing crops.’ So Bridges decided to bivouac too.fn18

They were away again at dawn, and at six-thirty saw half a dozen ‘uhlans’,fn19 as Bridges, along with everyone else, called all German cavalry with lances. They were in fact the 4th Cuirassiers of 9th Cavalry Division, and they were ambling down the road, lances slung, unaware of Bridges’ squadron, which he had moved into cover. He quickly ordered two troops to dismount for ‘fire action’, keeping the other two, under Hornby, mounted ready to charge.

At about 300 yards something spooked the Germans and they turned about, whereupon Bridges ordered the two troops to give chase, remounting the others and following at the trot. After a mile of galloping, Hornby came up against a half squadron of the Cuirassiers in a village street – and charged. As they clashed he drove his sabre into the chest of one of them, becoming the first man of the BEF to kill a German (barring, possibly, the slayer of the pilot of the Albatross the day before). His orderly, Private Tilney, had a hard time trying to follow suit, finding himself ‘kept busy by a big blond German trying to poke his lance into me. I could easily parry his lance but could not reach him.’

The lance was not intended for close-quarter fighting, even less so in a confined space, and several ‘uhlans’ threw theirs down and tried to surrender. In the heat of the fighting, however, ‘we weren’t in no mood to take prisoners’ wrote another trooper; ‘and we downed a lot of them before they managed to break it off and gallop away’.

Again the Dragoon Guards gave chase.

Having put a few hundred yards behind them, the Germans dismounted and opened fire on their pursuers. Hornby and his men followed suit, bullets flying about their ears as they got the horses into cover behind a chateau wall. Corporal Ernest Thomas was one of the first into a firing position: ‘I could see a German cavalry officer some four hundred yards away standing mounted in full view of me,’ he recalled. ‘I took aim, pulled the trigger and automatically, almost instantaneously, he fell to the ground’.

Kneeling, unsupported, at 400 yards – it was a fine shot, testament to the hours that the cavalry had put in at the butts before the war. Thomas was the first man of the BEF to fire his rifle at the enemy (at least from the ground at other than aircraft).

The Germans now broke off the action and withdrew. Bridges concluded that he had run into the divisional advance guard, and expecting a follow-up in strength decided to withdraw before the squadron could be outflanked. The action had demonstrated, in miniature, the futility of the either/or absolutism of the arme blanche debate.

Elsewhere the cavalry were having similar dustings. Brigadier-General Sir Philip Chetwode’s 5th (Independent) Cavalry Brigade, who were covering the advance of Haig’s I Corps, ran into artillery and heavy rifle fire near La Louvière, which was answered with accurate rifle fire by the Scots Greys (the arme blanche debate already looking sterile) and the 13-pounders of E Battery. A patrol of the 20th Hussars, another of Chetwode’s regiments, got to within 25 miles of Brussels before finding they had ridden into ‘vast masses of Germans of all arms’ and had to gallop for it in a hail of bullets, one or more of which brought down the horse of Private Thomas O’Shaughnessy. Remarkably, O’Shaughnessy was able to evade capture and managed to rejoin his regiment four days later in plain clothes (risking summary execution as a spy), having got through the German lines by playing deaf and dumb – ‘not an easy subterfuge’, says the regimental historian, ‘for an Irishman’.fn20

But while the Cavalry Division was reporting enemy in large numbers approaching from the north and north-east, an RFC reconnaissance patrol spotted something even more ominous – a huge column (Kluck’s II Corps), moving westward on the Brussels– Ninove road, and from Ninove south-west towards Grammont (Geraardsbergen). Brigadier-General Sir David Henderson realized at once what it threatened – a massive envelopment of the BEF’s left wing. He took the report in person to GHQ. In fact, Belgian GQG had wired Joffre’s headquarters the evening before to say that a German corps approaching Brussels appeared to be wheeling south. The information failed to reach GHQ, however – or, at least, to do so in the unequivocal language in which it had been sent from Brussels. Nor did the RFC report seem to make much impact.fn21

Wilson, though, clearly having thought a little more about Spears’ report the night before, had persuaded Sir John French to take a drive to see Lanrezac (whatever else may be said of Wilson, his powers of persuasion were prodigious: after the ‘pour pêcher’ quip, Lanrezac was the last man that French wanted to see). They set out ‘in the very early hours of a beautiful August morning’, and then, quite by chance – the greatest of good chances (for the encounter would save the BEF a terrible mauling) – not far into the French sector a dozen or so miles south of Maubeuge they met Spears’ car coming from the opposite direction, which they managed to flag down.fn22 Spears records: ‘I well remember the place’ (as a subaltern meeting a field marshal undoubtedly would): ‘quite a number of French soldiers, a couple of companies perhaps, were halted on either side of the road, and stared suspiciously at these strange, khaki-clad, red-tabbed officers.’ He recounts how at dawn he had gone to the little hotel where the headquarters of Lanrezac’s 5th Army were messing in the hope of some coffee and something to eat, and been surprised to find it full of dishevelled, disorientated civilians, mainly women and children. They turned out to be refugees from the fighting near Charleroi; but Spears makes no mention of any untoward appearance of the poilus at this impromptu rendezvous, which is significant in the light of Sir John French’s account. Indeed, those Spears had seen earlier, not yet in action but all eagerness for it, were ‘fine young fellows … Their lightheartedness and exuberance were contagious’.

There was an estaminet close by the chance rendezvous, which Wilson now commandeered as a conference room. Spears recalled a table ‘piled high with dirty plates and cups … [that were] cleared aside and a map spread out’. There can have been few occasions in history when a subaltern – even a lieutenant of hussars – has briefed a field marshal at so critical a moment; and certainly not in such comical surroundings, for the propriétaire now began defiantly, and noisily, washing the dishes in a tub in the corner of the room, stopped only with some difficulty by Spears’ accompanying French officer to allow him to resume his briefing.

Spears began by giving the field marshal the situation as 5th Army headquarters understood it that morning. X Corps had been ‘knocked about a good deal’ but were still intact, and then he repeated what he had told Wilson the night before – that Lanrezac’s appetite for the offensive was gone, and that the intelligence staff believed that the strength and extent of the German advance beyond the Meuse could mean but one thing: an enveloping movement on a huge scale. French asked about Sordet’s cavalry corps, and when it might move to cover his left, to which Spears was only able to say that he understood it to have withdrawn to somewhere about Merbes-le-Château, between Charleroi and Maubeuge (to the rear and right of the BEF’s I Corps).

French then asked where Lanrezac himself was, and on hearing he was at Mettet, south-east of Charleroi, some 30–40 miles’ drive, decided not to continue. Spears tried to persuade him otherwise – testament to his unusual strength of character – but failed: a C-in-C’s time was too valuable, said French, though in his own account he registers only his concern that there appeared to be ‘some difficulty in finding General Lanrezac’.

It is perfectly understandable that the commander of the BEF would not want to waste time driving round the French countryside in search of Lanrezac, but it is difficult to imagine what could have been more valuable at that point than to speak face-to-face with the commander of the army on which the security of his own command largely rested. That he risked being received with the same offhandedness as the week before, and having to speak through interpreters, could be of no account: he needed to know, in detail and with absolute assurance, what the intentions were of the troops to his right, and what troops, if any, would be on his left. Sending Wilson, at least, would have been a better option than turning back for Le Cateau. Joffre would have thought nothing of 40 miles on French roads; but, then, his driver was the winner of the French Grand Prix, Georges Boillot, not a sergeant of the Army Service Corps.

What pressing concern reversed the commander-in-chief’s intention? It seems, in fact, that he had already concluded that Lanrezac’s 5th Army was not merely abandoning the idea of the offensive, it was abandoning the field: ‘There is an atmosphere engendered by troops retiring, when they expect to be advancing, which is unmistakable to anyone who has had much experience of war,’ he would write.

It matters not whether such a movement is the result of a lost battle, an unsuccessful engagement, or is in the nature of a ‘strategic man![]() uvre to the rear.’ The fact that, whatever the reason may be, it means giving up ground to the enemy, affects the spirits of the troops and manifests itself in the discontented, apprehensive expression which is seen on the faces of the men, and the tired, slovenly, unwilling gait which invariably characterizes troops subjected to this ordeal. This atmosphere surrounded me for some time before I met Spiers [sic] and before he had spoken a word. My optimistic visions of the night before had vanished, and what he told me did not tend to bring them back … and therefore I decided to return at once to my Headquarters at Le Cateau.

uvre to the rear.’ The fact that, whatever the reason may be, it means giving up ground to the enemy, affects the spirits of the troops and manifests itself in the discontented, apprehensive expression which is seen on the faces of the men, and the tired, slovenly, unwilling gait which invariably characterizes troops subjected to this ordeal. This atmosphere surrounded me for some time before I met Spiers [sic] and before he had spoken a word. My optimistic visions of the night before had vanished, and what he told me did not tend to bring them back … and therefore I decided to return at once to my Headquarters at Le Cateau.

Yet on return to Le Cateau, where he was greeted by the skirl of pipes of the Cameron Highlanders, the GHQ guard, the commander-in-chief made no change of plan and issued no new orders. There was no talk whatever – as Wilson’s diaries confirm – of even halting the forward movement, let alone going on the defensive; and certainly not of any retrograde movement. French’s memoirs say one thing, his actions another. It is fruitless to speculate why.

One man was taking no chances, however. The commander of the BEF might delay his decision to change course and then rely on his artillery to get him out of trouble; his chief of logistics could not. In a withdrawal, stores unloaded had to be reloaded (or else abandoned), waggons plying forward from the distribution points had to be turned round, roads cleared for the marching troops, new replenishment points found … And the hard-headed Quartermaster-General, Wully Robertson, was already discussing contingency plans with Major-General Robb, commanding the lines of communication, in case the BEF were indeed forced to retreat.fn23 And soon the BEF would have cause to be grateful for his foresight, as well as for his robust decisions when the retreat actually began.

But for all the brilliance of his logistical staff work in the weeks ahead, it is difficult not to think that, seniority notwithstanding, Robertson should instead have been in the post for which his experience and temperament so perfectly suited him – the BEF’s head of intelligence. That job was filled by Colonel (from November, Brigadier-General) George Macdonogh, lately head of Section 5 of the War Office intelligence division, concerned with internal security (what would become in part today’s MI5). Macdonogh was brilliant; of that there was no doubt. He and a fellow sapper – James Edmonds, who would become in part the official historian of the Great War – had achieved such high marks in the staff college entrance exam in 1896 that the results, it was said, were adjusted to conceal the margin between them and their classmates (who included Robertson and Allenby). But Robertson had an impact that the intellectual, Jesuit-educated Macdonogh did not. Had he been in the other man’s place in the BEF’s ‘deuxième bureau’, there is every likelihood that on 22 August the infantry would have been digging defensive positions in front of the fortress of Maubeuge, not marching north in the expectation of going to it with the bayonet.fn24

For despite the growing evidence French, on seeing the reconnaissance reports brought by Henderson on the twenty-second, had reckoned that ‘there still appears to be very little to our front except cavalry supported by small bodies of infantry’. And it was on this basis that he had sent a not discouraging, though a shade ambiguous, message to Lanrezac:

I am waiting for the dispositions arranged for to be carried out, especially the posting of French Cavalry Corps on my left. I am prepared to fulfill the rôle allotted to me when the 5th Army advances to the attack. In the meantime, I hold an advanced defensive position extending from Condé on the left, through Mons to Erquelinnes, where I connect with two [French] Reserve Divisions south of the Sambre. I am now much in advance of the line held by the 5th Army and feel my position to be as forward as circumstances will allow, particularly in view of the fact that I am not properly prepared for offensive action till to-morrow morning, as I have previously informed you …

Only late that evening did the penny at last drop. The remarkable Spears had been active all day, learning that Lanrezac’s III Corps was falling back to a new (‘unfortified’) defensive line having been ‘roughly handled’ in the morning – one of its divisional commanders seriously wounded by rifle fire – and that 5th Army would in consequence be bowed back with its centre some 5–10 miles south of the Sambre. This would place the BEF at Mons about 9 miles ahead of the main French line, though Spears did not consider this calamitous. The 5th Army was certainly not beaten: its two ‘wing’ corps were intact, and there was every reason to suppose that the two centre corps would be able to recover, for ‘the morale even of those units which had suffered most was good’. The problem lay not with the left-wing, XVIII Corps, but with the gap between it and the BEF, not least because two reserve divisions ordered forward by Lanrezac that afternoon to beef up the left would not reach the Sambre until late the next day. But Spears’ worry was that Sir John French might still believe that Lanrezac intended attacking. At 7 p.m. therefore he set off again for Le Cateau, ‘feeling anything but happy: the responsibility of having to report a situation so serious [with no information beyond what he had been able to glean himself] that it must necessarily profoundly influence British plans overwhelmed me with anxiety’.

He was also exhausted, but fortunately on arrival the eminently sensible Macdonogh gave him half a bottle of restorative champagne and – perhaps more importantly – reassured him in his estimate of the situation with more corroborating reports from the RFC.

Sir John French was dining late, but he came out at once to hear Spears’ report. Having listened to it in silence – testimony to both its clarity and its authority – he told both Spears and Macdonogh to wait in the dining room while he and Sir Archibald Murray, the chief of staff, talked. Spears recalls his dismay on hearing, as he waited, the GHQ staff officers around the map-covered table and the liaison officers from I and II Corps discussing the general advance that was still planned for the following day.

After twenty minutes the door opened and a grim-faced Murray broke the spell. ‘You are to come in now and see the Chief,’ he said to the staff. ‘He is going to tell you there will be no advance. But remember there are to be no questions. Don’t ask why. There is no time and it would be useless. You are to take your orders, that’s all.’

They did, and took them thence to their respective corps commanders, who received the orders rather differently. Smith-Dorrien, having only just taken over II Corps, remained ‘in blissful ignorance of the situation’, for he was allowed to sleep on. Haig, on the other hand, at I Corps, was dismayed at the order to take up a front from Mons to Peissant ‘without delay’, which seemed to him ‘ill considered … in view of the condition of the reservists in the ranks, because it meant a forced march by night’.fn25

Doubtless he believed that all would be made clear at the conference Sir John French had ordered for five-thirty the following morning at II Corps headquarters.

And doubtless, too, before Spears’ arrival, the commander-in-chief had himself been hoping for a decent night’s sleep. Now he would have to cope with several hours fewer. But then another visitor arrived to disturb the chief’s repose. Close to midnight, Colonel Huguet came to the chateau with one of Lanrezac’s officers bearing an extraordinary request: le général wished the BEF to attack the flank of the German forces that were assailing 5th Army.

This was a sea change in the situation on Joffre’s left flank – and had it not been for Spears’ initiative, it would have been the first that French had heard of it. He pondered for a moment and then replied that he could not commit to an attack before discovering what lay to his front – ‘until he got reports from his aeroplanes’, Wilson says in his diary – but that he would at least stand on the Mons line for twenty-four hours. In the circumstances it was a good decision, which would only have been better had he made the decision to take up proper defensive positions on the Mons line – in other words, to dig in. Clearly he felt impelled by straightforward loyalty to an allied general under pressure: if the RFC at daylight found no enemy to his front he could indeed incline his advance to the east to attack Lanrezac’s Germans in the flank. But equally, too, he appears still to have been infected by Wilsonian optimism.fn26

However, the suddenness of the request and the part-withdrawal of 5th Army without telling him had their effect on French’s trust in Lanrezac, which within days would precipitate an almost total breach between the two men. For it did not help that Lanrezac was evidently trying to conceal the state of affairs on the left flank, telling GQG that afternoon that the BEF was ‘still in echelon to the rear of the Fifth Army’, although at that very moment II Corps was arriving at Mons, as French had already told him – ‘I hold an advanced defensive position extending from Condé on the left, through Mons to Erquelinnes’ – and I Corps was well north of Maubeuge and level with the left wing of Fifth Army and Sordet’s cavalry corps. In any case, if the BEF were in echelon to the rear, how could they attack the enemy in the flank? If Lanrezac did indeed know the true dispositions – as he must have, for Huguet had been given copies of the movement tables (and Lanrezac was asking for the attack to take place as soon as it was light) – even allowing for the fact that the BEF was still moving, and therefore a part of it would still be behind his left flank, what was the point of telling GQG a half-truth?

Could it have been that Lanrezac was preparing his alibi? Joffre had already removed several generals from command, notably in the 1st and 2nd Armies attacking in Alsace-Lorraine: they were sent to specially appointed quarters at Limoges in west-central France and isolated from all contact with either Paris or the army (coining the verb limoger). Lanrezac, having failed to make any forward movement as instructed by Joffre, would have been only too aware that a railway warrant for Limoges had probably been made out for him in pencil; any sign of retreat would see it inked in. How useful it would be therefore to blame the BEF’s tardiness in coming to his aid. This was certainly Spears’ considered view.fn27

Meanwhile the last of the infantry were slogging up to Mons with rifle and pack, shepherded by the hussars of the divisional cavalry squadrons. Frank Richards could count himself lucky, though: he and the rest of the 2nd Royal Welsh Fusiliers were taking the train. As part of the hastily formed 19th Brigade they were being railed from various places along the lines of communication (in Richards’ case, Amiens), where they had been guarding key points, to Valenciennes, not 10 miles from where they would first see – or rather, hear – action. But if they were welcome reinforcements on II Corps’ left, they were certainly not an RSM’s delight: ‘The majority of men in my battalion had given their cap and collar badges to the French ladies they had been walking out with, as souvenirs, and I expect in some cases had also left other souvenirs which would either be a blessing or curse to the ladies concerned,’ wrote Richards.

For single men in barracks don’t grow into plaster saints.

fn1 They would be reinforced the following day by the 19th Infantry Brigade (another 4,000 men), hastily formed from the lines-of-communication battalions which, their work now largely done, were being railed north.

fn2 Hasty defence: ‘A defence normally organized while in contact with the enemy or when contact is imminent and time available for the organization is limited. It is characterized by improvement of the natural defensive strength of the terrain by utilization of foxholes, emplacements, and obstacles.’ Meeting engagement: ‘A combat action occurring when a moving force, incompletely deployed for battle, engages an enemy at an unexpected time and place.’ NATO Glossary of Terms and Definitions, AAP-6 (2010).

fn3 In his diary Wilson wrote: ‘During the afternoon many reports of Germans advancing in masses from north and east, also that Namur was going to fall [its evacuation was begun next day]. I can’t believe this.’

fn4 It is even more surprising as the RFC’s commander, Brigadier-General Sir David Henderson, had written two highly regarded pamphlets: Field Intelligence: Its Principles and Practice (1904) and The Art of Reconnaissance (1907).

fn5 Beta had been built in May 1910 and consisted of a long frame with a centre compartment for the crew and engines. A 35 hp engine drove two wooden propellers. At the army manoeuvres that year she remained in the air for nearly eight hours on one patrol. In 1912, re-equipped with a 45 hp engine, she had a maximum speed of 35 mph and could carry fuel for about eight hours with a crew of three.

fn6 General Sir George de S. Barrow, The Fire of Life (London, 1942). At fifty, Barrow was only three years younger than Allenby himself, but he had a spectacularly good war – hardly surprising, given the Mons initiative – becoming chief staff officer of the Cavalry Division, then of the Cavalry Corps when it was formed, then X Corps, and 1st Army, then commanding successively 1st Indian Cavalry Division, 7th Division, the Yeomanry Division, 4th Cavalry Division, XXIV Corps, and finally the Desert Mounted Corps in Palestine under Allenby.

fn7 Joffre was also buoyed up by the news of the Russians’ success in East Prussia, into which they had advanced almost a fortnight earlier. On 20 August the Germans were thrown back at Gumbinnen, and by the twenty-second the Russians had twenty-eight army corps in contact with the Germans. It could not be long, he reckoned, before this would have a drawing-off effect on the Western Front.

fn8 A number of histories (including Richard Holmes’s biography, The Little Field Marshal: A Life of Sir John French, London, 1981) date his arrival on the twentieth, but Smith-Dorrien’s diary says firmly the twenty-first; and, indeed, the general chronology makes more sense thus. Either way, II Corps was preparing to move north on Mons, or was already on the move, when he arrived.

fn9 Horace Smith-Dorrien, Memories of Forty Years’ Service (London, 1925).

fn10 Nevertheless, Kitchener was unable or unwilling to save Smith-Dorrien when French removed him from command of 2nd Army the following May. At the time of French’s publishing 1914 both Kitchener and Douglas were dead. Sir John Fortescue, the great historian of the army, writing of French’s account in the Quarterly Review in October 1919, described it as ‘one of the most unfortunate books ever written’. Much of the correspondence with Smith-Dorrien, especially that of Edmonds, the official historian, is in the National Archives; its excoriation of French does not make pretty reading.

fn11 Quotations in this and the following paragraphs are from Memories of Forty Years’ Service. At this meeting, Smith-Dorrien asked French for formal permission to keep a diary, since, he explained, the King had told him to ask the C-in-C for such permission in order that he could write periodically to ‘keep His Majesty posted in all pertaining to my command’. Sir John French could hardly refuse the King, but it could not have pleased him, knowing also that Haig too had a direct line to the Palace.

fn12 Blue because in military map marking, the enemy is shown in red, and friendly forces in blue.

fn13 Spears makes an interesting observation about the BEF’s staff cars: they were prone to breaking down, unlike those of the French, because they had been bought ‘straight out of the shop windows’, and not run in and tuned up. The French, on the other hand, had requisitioned all theirs in good running condition. Some of the best of the BEF’s cars were those given – loaned – by prominent figures such as the duke of Westminster and the earl of Derby, sometimes complete with chauffeur.

fn14 General Johan von Zehl, commanding VII Corps (Bülow’s 2nd Army), Das VII. Reserve-Korps im Weltkriege von s. Beginn bis Ende 1916 (1921), quoted in Herwig, The Marne, 1914.

fn15 Like everyone else, for no one had predicted the tactical circumstances in which Namur would find itself – effectively abandoned. Generaloberst Karl von Bülow’s army laid siege on the twentieth, bringing up the big guns from Liège. It was all over by the twenty-fifth, at which point, by Schlieffen’s plan, the road to Paris (or, at least, to the rear of the French army) lay open.

fn16 De Lisle, who would succeed Allenby in command of the Cavalry Division, was never popular with his officers. It perhaps went back to his time as adjutant of the Durham Light Infantry in India, where he had trained and led the DLI’s polo team to victory in the inter-regimental cup – a victory (the infantry over the cavalry) that should simply never have happened. He had later transferred to the 1st Dragoons (The Royals). Opinions of his character and ability are as mixed as those of Haig.

fn17 Uhlan regiments were modelled on the Polish lancers of the Napoleonic era, though because all German cavalry – hussars, dragoons, cuirassiers – carried the lance, ‘uhlan’ became a generic term for men on horseback carrying lances. The lance consisted of a tube made of rolled steel-plate 3.2 metres long (10 feet 6 inches) weighing 1.6 kg (3 lb 9 oz), and a four-edged tempered steel spearpoint. By contrast, the lance carried by the British cavalry (lancer regiments) consisted of a steel head mounted on an ash stave, with an overall length of 9 feet 1 inch.

fn18 No such orders to avoid damage to crops had been given the Germans. To Kluck’s regiments, damage to crops, and much else, was not just unavoidable; it was war. A few days later they would pour petrol over the medieval manuscripts in the library of Louvain’s Catholic University and burn the place to the ground.

fn19 All timings were Greenwich Mean Time (in modern military terminology, ‘Zulu Time’), or Western European Time as the French called it. On 23 August 1914 at Mons sunrise was at 4.44 a.m., and sunset at 6.49 p.m. The time of first and last light – the sun’s light from below the horizon (or, as the Highway Code has it, ‘lighting-up time’) – varies depending on the cloud, but is generally about thirty minutes before and after sunset respectively. It is sometimes defined as the time at which colours can be discerned, but for soldiers it is the point at which night-time routine – strengthening the position, sentries, patrolling or sleeping – changes to that of day (and vice versa), with movement becoming respectively easier or more restricted. It is the point also at which an enemy attack is likeliest (particularly first light) and therefore when a body of troops stands to arms. The term ‘stand to arms’ (or simply ‘stand to’) means to adopt a position from which to fight in case of attack.

fn20 Lieutenant-Colonel L. B. Oatts, The Emperor’s Chambermaids: The Story of the 14th/20th King’s Hussars (London, 1973).

fn21 French records that ‘At 5.30 a.m. on the 21st I received a visit from General de Morionville, Chief of the Staff to His Majesty the King of the Belgians, who, with a small staff, was proceeding to Joffre’s Headquarters … He confirmed all the reports we had received concerning the situation generally, and added that the unsupported condition of the Belgian Army rendered their position very precarious, and that the King had, therefore, determined to effect a retirement on Antwerp, where they would be prepared to attack the flank of the enemy’s columns as they advanced. He told me he hoped to arrive at a complete understanding with the French Commander-in-Chief.’

fn22 They had possibly set out later than French recalled, since Spears had already visited several advanced units that morning to gain for himself an impression of the views of the operations staff.

fn23 In fact he was following Field Service Regulations: ‘Orders for a possible retreat should always be thought out beforehand in case of need, but they should not be communicated to the troops before it becomes necessary to do so.’

fn24 Macdonogh’s effectiveness was undoubtedly reduced by suspicion of his Catholicism. He had been one of the few senior officers to advocate the use of force in Ulster during the home rule crisis (as had Churchill); the Curragh ‘Mutiny’ had opened fissures within the army, albeit tiny cracks compared with the gulf between the brass hats and the frocks. In 1916 he would return to the War Office as director of military intelligence and do brilliant work; but he suffered from poor relations with Haig and his chief of intelligence, Charteris, who in November 1917 would write to his wife: ‘My chief opponents are the Roman Catholic people, who are really very half-hearted about the whole war and have never forgiven DH unjustly for being Presbyterian.’

fn25 Haig’s diary is somewhat confused at this stage, the chronology not wholly reliable.

fn26 French would never have described himself as innovative, but in many respects he was quick on the tactical uptake, realizing soon enough that the real intelligence he needed would come from the RFC – who had the necessary range and perspective – rather than from his beloved cavalry, who would be drawn inexorably into the actual fighting to help extricate the infantry during the prolonged withdrawal after Mons.

fn27 Lanrezac’s memoirs are full of infelicitous references to the BEF compared with the French army at this time, of their ‘not speaking the same language and having different mentalities’ etc. As for the fear of being limogé, in less than a month fifty-eight senior officers would be sent to the rear. By December, 40% in all had been removed from post. But Sir John French is, it has to be said, unreliable in his recollection of, or explanation of, his decision to abandon the advance on the twenty-third. His diaries suggest it was the enemy situation that was the cause, although no new information reached him during the evening of the twenty-second (and GQG reports of increasing strength were still being considered a shade over-egged, though not by Macdonogh). His description in 1914 of the poilus’ ‘tired, slovenly, unwilling gait’ on the morning of the twenty-second is reflected in his diaries, and conflicts with Spears’ impressions. Spears had not, of course, ‘much experience of war’, but his description of the morale of 5th Army is so positive that it seems unlikely that he had merely failed to notice its absence. Nor, indeed, on the morning of the twenty-second had 5th Army’s X Corps made much of a retrograde movement – certainly not enough to have the effect in the rear areas that French describes. Besides, as John Terraine puts it succinctly in Mons: The Retreat to Victory (London, 1960), the poilus, overloaded with equipment which made them lean forward on the march, as if bowed by fatigue, ‘Straggling along in loose formation, all over the roads, out of step … were a startling sight to English observers; but they usually “got there”, all the same.’ It was surely Spears’ report that changed the orders for the BEF from advance to defence; and perhaps the realization that if 5th Army had been so roughly handled, the Germans were indeed advancing in strength. Either way, it does not speak well of GHQ’s coordination with 5th Army (relying on a single subaltern liaison officer), and its appreciation of intelligence. Sir Walter Raleigh’s official history, The War in the Air (London, 1922, and therefore subject to correction by French) is unequivocal: ‘Sir John French on the evening of the 22nd held a conference at Le Cateau, whereat the position of the Germans, so far as it was then known, was explained and discussed. At the close of the conference Sir John stated that owing to the retreat of the French Fifth Army [author’s italics] the British offensive would not take place.’