There was this shock that someone would have the nerve to try to take what we were doing and castrate it to make it more commercially viable. JOHN BRODEY

THE

BATTLE

JOINED

It’s interesting to consider that one of WBCN’S cornerstone talents, who would remain with the station for thirteen years, developed his Boston radio career by working to co-opt the very audience that “The American Revolution” had fostered since 1968. Ken Shelton would participate in a near-dismantling of Camelot, a surprise attack from across the radio dial that WBCN’S denizens, absorbed in their own greatness, would remain badly naive of until it was almost too late. As one of the standard-bearers at the upstart WCOZ, Ken Shelton was destined to plunder large numbers of listeners from the ranks of a station once considered bulletproof, protected by the unwavering support from its community since inception. But as the seventies passed the halfway point, ’BCN, in a languished state with a depleted rank of veterans, found itself vulnerable to a new rival with roots in an old approach — the Top 40 system of concentrating more attention on fewer songs.

As a kid in Brooklyn, Ken Shelton grew up loving the music of Elvis Presley and the pop hits of the late fifties and early sixties, furtively listening at night to a small transistor radio hidden under his pillow. Later, he discovered and embraced the sixties counterculture, hanging out in the Village and seeing the Fugs and the Blues Project as well as the Band at the Fillmore. He graduated from college with a bachelor’s in speech and theater, ostensibly for a career in television. “It was 1969; Vietnam was still going on, so the goal was to stay in school,” he remembered. “I looked around for graduate schools and ended up at BU.” When Shelton arrived in Boston, the first thing he did, like everybody else, was set up his stereo system. “I scanned up and down the dial and suddenly I heard ‘Witchi-Tai-To’ by Everything Is Everything. [I] never heard that before. So, for the next two years, I did not move that radio dial from ’BCN; I couldn’t tell you the name of any other station.”

After graduation, considering Shelton’s distinctive deep voice and passion for radio, it seemed a likely career choice, but marrying his college sweetheart meant that he better bring home the bacon — and quickly. Since he’d studied for a job in television, Shelton got a job at Channel 4 (WBZ-TV) as an assistant director, working nights, weekends, and holidays, and becoming the floor manager on Rex Trailer’s Boomtown kids show. “Rex used to ride his horse into the studio, and one time, there was a big [accident] on camera,” Shelton recalled, pinching his nose and chuckling. “Somewhere was a pot of gold and some creativity in TV production, but it sure wasn’t there!” Then, the restless director ran into Clark Smidt, one of his grad school buddies, who had worked his way into WBZ’S radio division selling ads for the AM station and managing the younger FM signal, which broadcast classical music by day and jazz at night. Shelton expressed his unhappiness, mentioning he was tired of sweeping up after . . . the talent. Smidt rapidly became Shelton’s ticket, finagling his buddy into the radio division as his programming assistant.

When the parent company, Westinghouse, decided to flip WBZ-FM over to a contemporary Top 40 rock format, the station became an automated jukebox with Smidt and Shelton picking the songs and voice-tracking the entire broadcast day on tape. “It went on the air December 30, 1971, and the first record was American Pie, the long version,” Smidt recalled. “It was a tight playlist, but we did slip in a few album cuts.” The pair came up with innovative features like the “Bummer of the Week,” where listeners suggested a song they hated, and the DJS would, literally, break the vinyl on the air. The format quickly generated impressive ratings, even if the company didn’t want to put too much effort into it. “The general manager came in one day,” Shelton recalled, “and said, ‘We don’t want you guys to have too much of a presence; it’s the music [that matters], so from now on, no last names on the air. You’re Clark. You’re Ken.’ I had a little desk in Clark’s office and he would call over to me, ‘Hey Captain!’ I thought that ‘captain’ had a nice ring to it. They said no last names, but nothing about nicknames, so, I started using ‘Captain Ken’ on the air and it stuck like Krazy Glue!”

At the end of ’74, Smidt and Shelton made a fervent pitch to Westinghouse for more resources, but the company balked at the idea of pumping additional dollars into WBZ-FM. “The head of Westinghouse thought FM was just a fad,” Shelton bemoaned. “Our hearts were broken. Clark didn’t stay much longer, and I was only there a few months after that.” But the lessons learned in that experience proved that there was room for a station in Boston that played a mixture of rock-oriented Top 40 hits and appealing songs from LPs, which had become the medium of choice for much of the college-aged audience. In 1972, Blair Radio had purchased WCOZ, a beautiful music FM station with the slogan of “The Cozy Sound, 94.5 in Boston.” Three years later, “Clark got the job as program director to turn ’COZ into a rocker and go against ’BCN,” Shelton stated. “I was the first person he hired.”

WCOZ switched to rock programming on 15 August 1975 and then, during the Labor Day weekend, aired a syndicated special called “Fantasy Park: A Concert of the Mind.” Smidt marveled, “What a reaction that got!” Originally produced at KNUS-FM in Dallas and broadcast in nearly two hundred markets, the two-day “concert” generated excitement in nearly every market it aired. Songs from existing live albums were assembled to make it appear as if all the best rock bands in the world were together on the bill of some incredible concert that was being broadcast as it happened. “It was a three-day fictional Woodstock-like event designed for radio,” said Mark Parenteau, soon to be hired by the newly minted WCOZ. “People weren’t sure if the concert was real.” David Bieber, at the time a freelance marketing specialist, was also impressed: “It was a total cliché of radio being a theater of the mind, grabbing live album tracks and presenting this concert that had never occurred. ’COZ just came along, taking all these marquee names that ’BCN had been present with during the creation of their careers, and stole the thunder.”

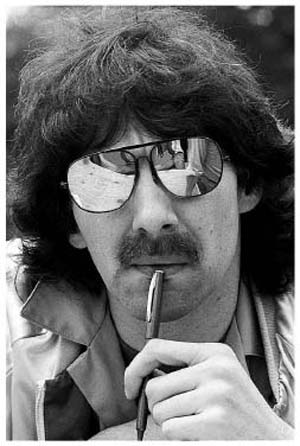

Mark Parenteau gets his break at Boston’s Best Rock: 94 and a half, wCoZ. Photo by Dan Beach.

After WCOZ’S dramatic arrival, Clark Smidt began replacing the automated programming with live DJS, installing his protégé Ken Shelton in the early evening. George Taylor Morris, Lesley Palmiter, Lisa Karlin, Stephen Capen, and others were soon to follow. “Then there was Mark Parenteau,” Smidt laughed. “I remember him telling me, ‘I’m so broke, I’ve got to get hired. I had to run the tolls from Natick just to get here!’” Parenteau then suggested that Smidt hire Jerry Goodwin, one of his buddies at WABX-FM in Detroit, who had been a veteran announcer with his “deep pipes” at several A-list radio stations around the country. Goodwin, a native New Englander, had returned to Boston to pursue a PhD in social ethics at Boston University’s School of Theology. “Mark [Parenteau] seriously hunted me down. He said, ‘Give up this religious zealotry you’re into. Come back to where you belong!’ It seemed like a good idea, so I started working for ’COZ [as] their production director and doing weekends.”

WCOZ’S list of album tracks and mainstream hits included songs that would become classic rock standards many years later: “The Joker” from Steve Miller, “Baba O’Riley” by The Who, Elton John’s “Saturday Night’s Alright for Fighting,” and “Sweet Emotion” from Aerosmith. Along with a tighter playlist, ’COZ guaranteed fewer commercials, less talk from the DJS, vibrant station identifiers, and up-tempo production. Smidt called it, “Boston’s Best Rock: 94 and a half, WCOZ.” The mix appealed to an audience that suddenly had an alternative to the only FM rocker in town. “The first book [ratings period], fall ’75, was a legendary one,” Smidt recalled. “For listeners twelve years and older, WCOZ jumped to a 2.9 [share] right out of the box, and ’BCN had a 1.9.”

“The purists among the radio elite in Boston were horrified,” Parenteau pointed out, “but the audience dug it.”

“[WCOZ] had a focus to their programming, and what had been an advantage at ’BCN turned into a confusion,” David Bieber reasoned. “WBCN had a story to tell and their story got stolen; a Reader’s Digest version of the station defeated them.”

“When ’COZ happened, it was like a pail of cold water,” Tim Montgomery said. “I remember thinking at the time, ‘Man to man, we are a little indulgent.’”

“There was so much of that self-sanctioned, self-righteous thing in radio, and at ’BCN, at the time,” added Parenteau. “For instance, if it was a windy day, each jock would come in with the same genius idea; you’d hear ‘Wind’ by Circus Maximus, ‘The Wind Cries Mary’ [from Hendrix], and ‘Ride the Wind’ by the Youngbloods—forty-five minutes of fuckin’ wind songs!”

Not only did Clark Smidt and his tighter playlist exploit the inconsistencies of a station where the individual radio shifts were self-governed, but also certain songs and genres either intentionally or inadvertently missed at WBCN became important building blocks of WCOZ’S programming. Ken Shelton stated, “’BCN played the Allman Brothers, but considered Skynyrd to be a cheesy bar-room rip-off. [But] people were calling ’COZ: ‘Play “Free Bird”! Play “Free Bird”!’ ’BCN stopped playing ‘Stairway to Heaven.’ They must have looked at the log and realized that they’d played it five thousand times; wasn’t that enough? So, they started losing listeners to the ‘common man’ radio station.” ’BCN’S jocks reacted, feebly at first, not yet grasping the seriousness of the situation. “We just started making fun of them,” John Brodey remembered. “They were the fakes; we were the real deal.”

“They put on the cheesy announcers like Ken,” added Tim Montgomery. “Now, don’t get me wrong, he’s a fabulous guy and he [would have] a great career [later] at ’BCN, but back then, my God, he sounded like . . . an announcer! He had a nice voice!” But, no matter how little regard the WBCN jocks had for their streamlined challenger, the disdain was not enough to prevent WCOZ’S steady rise.

Aside from the listener’s acceptance, WCOZ also began to gain some measure of legitimacy within the music business as record labels recognized the value of promoting their releases on “94 and a half.” As ’COZ’S ratings swelled, a seesaw battle ensued, with each station racing to obtain exclusive association with the biggest talents of the day. Most often, WBCN could rely on the relationships it had fostered over the years with record promotion people and the bands themselves, many of whom had grown up with the station. However, that was not always the case, especially when WCOZ became more aggressive in pursuing its opportunities, as when Mark Parenteau pirated The Who right out from under WBCN’S nose. The original FM rocker had always enjoyed a tight relationship with the English band, dating back to even before Pete Townshend introduced Tommy on the air with J.J. Jackson in 1969, but that didn’t stop Parenteau from recognizing an opportunity and then exploiting it to the max.

On 9 March 1976, The Who returned to play Boston Garden, and although scheduled to be on the air later that night, Parenteau still had time to see a good chunk of the band’s performance before he’d have to leave. “While we were waiting for The Who to come on, all of a sudden there was this big commotion in the loge next to us; some trash was burning under the bleacher seats,” Parenteau remembered.

People started moving quickly, lots of screaming, “Get out of the way! Get out of the way!” This giant column of smoke rose up and hit the ceiling of the Boston Garden, then mushroomed out and settled back on the crowd. The fire alarms went on, all the emergency doors opened, and the Boston Fire Department came in with fire hoses to get this trash fire out. People were trying to find places to sit . . . in stairways, aisles; they moved people away from the fire, but they never closed the show down. Meanwhile during all this extra time, Keith Moon, the drummer of The Who, was doing what Keith Moon always did—getting really fucked up backstage. I think on a good night, they had that all timed out so there wasn’t this enormous break between bands, so he was just high enough to go on stage.

Finally the lights came down and everybody went “YEH!” The fire’s was put out, we weren’t gonna die, and everything was great. The Who came on and started playing, but when they went into the second song, Keith was all over the place; he raised his arms, hit the drums, raised his arms . . . and fell backwards right off the drum [platform] and out of sight! So, off they went and the houselights came back on. Everybody was all tuned up on whatever drugs they were doing and [going] “uhhh . . . what?” There was still smoke in the air, and it was cold because the doors were open; the fun had just been leached right out of it all. Then Daltrey came running [back] on and said, “It’s a bummer; our drummer is ill! But, we’re going to come back!” Everybody was booing, so we went backstage. I found Dick Williams and Jon Scott, the two heavies from MCA, the band’s record label. They said, “Oh, Mark . . . terrible . . .”

“Listen, here’s the hotline number; if you want, those guys can come over on the air and explain what just happened.” So I went back to the studio and told the whole story; the phones were buzzing with people being pissed off.

Parenteau was barely into his show when the hotline rang. “The security guard called and said, ‘There’s a Jon Scott down here with some other people and they want to see you.’” It was Roger Daltrey, who immediately wanted to go on the air. “He explained what had happened and said, ‘We’re going to come back,’ and gave the date [1 April]. So, the next day it was in the newspaper; the article mentioned he had come by WCOZ . . . and ’BCN had nothing to do with it. The ramifications were loud and long lasting. This was a major story, a major event at the Garden, a major band. That legitimized ’COZ as being the right station at the right time, where the action was, and a nail in the coffin of ’BCN—for what they were doing at that time. Norm Winer [must have] gone out of his mind!”

David Bieber observed that it was a most difficult period for WBCN: “The station was searching for its own meaning and what it was all about; if 1976 was the real challenge and crossroads time, then ’77 was the year of twisting in the wind and not knowing where to go.” Music was changing: from the radical underground rock of the late sixties and political Vietnam rants of the earlier seventies to a smoother, more mainstream, arena-rock style that sounded tailor-made for the streamlined WCOZ but was accepted with difficulty on the veteran station. Boston released its first album in September ’76; Steve Miller’s Fly Like an Eagle became one of the year’s biggest hits; and Frampton Comes Alive spent ten weeks atop the Billboard chart. “A more uniform, bland tone pervaded the FM airwaves,” summed up Sidney Blumenthal in the Real Paper in 1978. “Rock became commercial culture.” David Bieber added, “You had some acts that were originally great BCN [artists] now crossing over significantly into Top 40. For example, the monstrosity that Elton John became: complete indulgence and decadence, costumes instead of content.”

The only member of the full-time staff who seemed to thrive during this time was Maxanne, whose original disposition toward rock and roll had pointed the DJ toward the future way back in 1970. Her passion had helped ignite Aerosmith’s career, which by 1976 had resulted in two platinum albums, a handful of hit singles, and sold-out tours. A personal and professional interest in Wellesley singer and guitarist Billy Squier had helped his band Piper get a record deal with A & M, setting up his later, and significant, solo success in the eighties. Plus, as the Boston Phoenix reported in a retrospective article in June 1988, “Maxanne Sartori was an original champion of the Cars. Throughout ’76 and ’77 she played demo tapes of the band, providing it with a ready-made audience in a key college market when it signed with Elektra.” She told the Boston Globe in 1983, “I played the first Cars tapes so much that people at the station used to take the tapes out of the studio so I couldn’t play them!”

“Maxanne was the only jock who was really rocking,” remembered “Big Mattress” writer Oedipus, who was similarly excited by what he called “the nascent rock and roll scene developing in the clubs.” Oedipus worked the morning show shift (paid by whatever records and tickets he could scrounge), headed home and slept all day, and then went out nightclubbing, returning to the station after last call. “I’d stay up and hang out with Eric Jackson or Jim Parry.” Not only did Oedipus get to know the overnight personalities at ’BCN, but he was also there when the news department reported for duty in the early morning. “John Scagliotti knew that I got around town, so he said, ‘Why don’t you report on what’s happening?’ I was able to go to all the concerts, the cabaret shows and all kinds of cultural happenings.” Oedipus began taping one-minute reports that ran in the afternoon on Maxanne’s show. “It got sponsored and I actually got paid. So, for my report, I made twelve dollars a week, and I sure needed it! On Fridays I’d get to ’BCN and wait for Al Perry to sign the damn checks; that was my food.” Because of his associations with Maxanne and the news department, Oedipus was not left high and dry when his mentor Charles Laquidara left WBCN for the “Peruvian” mountains in 1976. “I said, ‘Charles, I should take over for you.’ He looked at me and said, ‘Oedipus, you’ll never be hired at WBCN as a DJ!’”

With Al Perry, Norm Winer, and Laquidara gone, the rebuilding effort at WBCN began with the appointment of a new general manager, an experienced radio man named Klee Dobra, whom Mitch Hastings plucked from KLIF in Dallas. In late January 1977, the new boss brought in Bob Shannon, another outsider weaned on radio in Texas and Arizona, to assess the station and interview to be its next program director. Shannon camped out in a hotel room and tuned in the two radio opponents to see if he could determine why a young upstart was beating up Boston’s legendary FM veteran. “What I discovered after listening for awhile was that ’COZ was playing the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, and Led Zeppelin [while] ’BCN was playing Graham Parker and the Rumour. There was no question ’BCN was too hip for the room.” Shannon went back to Dobra: “I said, ‘With all due respect, three-quarters of the stuff I’m hearing on the radio station, I’ve never heard [in] my whole life. There’s a lot of people that want to listen to this radio station: they tune in, [but] they hate what they get, so they tune out.’” After being hired, the new program director worked on a plan to rescue the station, concluding, “At the time everybody played exactly what they wanted, and as a result, when people were great, they were great. But when they were not in a good mood, it was awful. Plus, there was no consistency from shift to shift.”

Shannon had some record cases built and then called on the staff to recommend the best albums in each category of blues, jazz, folk, R & B, and rock music. He ended up with a core library of two thousand records, which became the bulk of the station’s available on-air music. Then, only at certain times in each hour were the DJS given the freedom to access the additional, and gigantic, “outer” record collection. “The idea was to reduce the library to a workable number of tunes. In the beginning they hated it, but all of a sudden the station started sounding consistent.” Tommy Hadges, who had filled the morning gap following Charles Laquidara’s departure, said, “We began to have an awareness and desire to look from show to show, to have some sort of flow so it didn’t sound like six different radio stations.” But not everyone was amenable to the changes. The first to abandon ship was Andy Beaubien, who left his midday slot to pursue a career in artist management. Original ’BCN jock Joe Rogers, who had been back at the station since 1972 operating under his new radio moniker of Mississippi Fats, also departed. “I was having more trouble with the changes than most people; I was having . . . less fun. I think [’BCN] was wonderful for a long time and I can see why it was necessary for it to change, and so it did. It isn’t regrets; it was the sadness of watching . . . when all the jazz albums disappeared, all the blues albums, folk . . . . I felt, ‘I’m a dinosaur here.’”

Rogers signed off to pursue a dream he had fostered—starting his own restaurant—and Mississippi’s Soup and Salad Sandwich Shop opened shortly after in Kenmore Square. Virtually an art gallery that served food, the establishment featured a wall décor of huge pea pods, images of mustard, and other edibles rendered in gigantic size by students at the Museum School. “It was a lot of fun,” the new restaurateur enthused. “We had real and imaginary sandwiches—peanut butter to caviar. We charged people for peanut butter sandwiches according to their height: there was a pole by the cash register, and taller people would pay more. You could get a ‘Gerald Ford’ sandwich: cream of mushroom soup on white bread.” The pioneering disc jockey didn’t forget his adventures at WBCN: “I had a sandwich named the ‘Charles Laquidara,’ a custom prosciutto-based Panini with provolone and tomato. But prosciutto was so expensive that we would have had to lock it in the safe at night, so we compromised with Genoa salami.” He laughed, “We had a total of two customers who ever ordered the ‘Gerald Ford’; but the ‘Charles Laquidara’ ended up being much more popular than the president!”

WBCN lost its most powerful and distinctive personality when Maxanne decided to toss in the towel, exiting after her final show on April Fool’s Day 1977. “She was scared that I was going to change the radio station dramatically,” Bob Shannon concluded. But Maxanne also wanted to pursue a career in the record business, which made a lot of sense since she had always tuned in to new talent. Trading in her headphones, the jock picked up a job doing regional promotion for Island Records, later working in the national offices of Elektra-Asylum and eventually as an independent promoter. Replacing such a memorable talent was an important decision, and Shannon opted to move the infamous oddball Steve Segal (now referring to himself as Steven “Clean”), who had left ’BCN for the West Coast and then returned, into the afternoon drive slot. “On the air he was either brilliant or awful—no in between,” Shannon laughed. “One day he played a record by the Pousette-Dart Band and he came on the air and said, ‘That reminds me of a game I used to play when I was a little kid, called “Pussydarts.” What you do is take darts, throw them at the cats and try to pin them down.’ The animal-rights people went nuts. I mean, they were in the front lobby in thirty minutes!”

Shannon moved John Brodey into evenings and made him music director, and then planned to switch Tommy Hadges, who had inherited the morning shift out of necessity, into the midday slot. But, finding the right talent for mornings was a daunting task. Shannon flashed on a DJ he never met but had heard regularly on a small Tucson radio station back in ’72. “Matt Siegel did a night show there, and I used to sit in the bathtub, smoke a joint, and listen to him. I laughed a lot because he was so funny. So now, I started making calls . . . but I couldn’t find him; nobody knew where he was. The only thing anybody knew was that he had done the voiceover on a regional Fleetwood Mac spot for Warner Brothers.” That actually was true: Matt Siegel had left Tucson and headed for LA, snagging a lucrative freelance job making commercials for record labels. When that opportunity eventually played out, he hit the streets looking for another job but couldn’t find anything. With his money just about exhausted, Siegel phoned his best friend, who happened to live in Boston: “I said, ‘I have to come see you,’ took my last $300, and got to my buddy’s house in Brighton.”

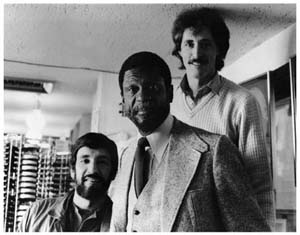

Charles Laquidara and Matt Siegel clowning around with Bill Russell. Who’s taller? Photo by Eli Sherer.

Matt Siegel was now hanging out in the same city as Bob Shannon, but neither of them knew it. “There was this guy, Steven ‘Clean,’ who I met in LA, and he worked for WBCN,” Siegel continued. “I figured I’d call him on a whim to see if there was something available because I was stone broke.” Siegel phoned, and then went to the station, but couldn’t find the DJ. “I was just coming up zeros. So I said, ‘I’d like to talk to the program director.’ I lied to them, saying, ‘It’s Matt Siegel from Warner Brothers in LA,’ hoping the word wasn’t out.” But, once his unexpected visitor’s name was passed along, Bob Shannon sat there stunned; the coincidence too outrageous to be real. “I told the secretary, ‘Ask him if it’s the Matt Siegel from KWFM in Tucson.’ She came back and said, ‘Yeah, that’s who he is.’ I couldn’t believe it!”

“[Shannon] looked at me and said, ‘Matt Siegel, how the hell are you?’ I was amazed. ‘You know me?’ He said, ‘I’ve been following your career.’ I said back to him, ‘I don’t have a career; what are you following?’” When Shannon invited Siegel out to lunch, the DJ was floored: “I felt like I was in the Twilight Zone; my luck was finally turning.”

“We were having lunch,” Shannon remembered, “I was talking and watching him, and he was really funny. Finally I said, ‘How would you like to do mornings on WBCN?’ He looked at me like I was the craziest person he’d ever met in his whole life.”

“[Shannon] said, ‘I can give you a job today. How’s $18,500?’ I went, ‘Uhhh, great!’” In moments, the unknown Matt Siegel became WBCN’S new morning drive announcer. However, this tale of perfect timing from mid-1977 was not quite over, as Siegel related: “The last part of the story is that three weeks later, Bob Shannon was gone. Gone! You want to talk about luck?”

“I was reasonably smart [about how to fix ’BCN] when I walked into that situation, but I was in over my head emotionally,” Bob Shannon confessed. “I was always the outsider, working long hours, alone—this red-headed, bearded asshole from Texas.”

“Bob actually did a lot of good things for the station,” Tommy Hadges admitted. “Whatever animosity existed was just a general unease of having somebody from the outside make all these changes; he wasn’t considered part of the ’BCN family.” When Shannon got a job offer for more money back in Dallas, he tendered his resignation. But just before climbing into his escape pod, he completed two more significant hirings, the first being Tracy Roach, a Brown University student and veteran of the campus radio station, WBRU-FM. The new jock started working weekends even before her graduation, becoming the youngest member of the WBCN air staff, and then bounced around as a full-timer before settling into early evenings. Roach had no experience with WBCN’S rich counterculture heritage, having only been thirteen years old when Joe Rogers dropped the needle on Frank Zappa back in ’68. She told Record World magazine in 1978, “Danny Schechter did an enormous retrospective on the great and glorious past at ’BCN, which I surely have a lot of respect for. But those days are over. There are new things to be done now.” As Roach settled into her job, Klee Dobra approved the deal to entice Jerry Goodwin from WCOZ. Then, as the ink on Goodwin’s contract dried, Bob Shannon disappeared. While his controversial six-month tenancy proved to be critical to ensuring ’BCN’S future, within a few years, the young Texan’s presence would be all but forgotten.

In the summer of 1977, Tommy Hadges stepped in as Shannon’s replacement. Although he’d stay less than a year, he was most proud of hiring three significant employees who were destined to shape and guide the station for years to come. The new program director agreed with his predecessor that the playlist needed to be focused and consistent from shift to shift but also believed that some degree of openness had to remain. Staying in touch with the latest artists and the newest trends in music was necessary to serve this latter goal. Hadges remembered asking the staff, “What is this alternative stuff coming out?” He referred to the punk movement building on both sides of the Atlantic, with Boston being one of the point markets for the edgy style. “My roots were folk-rock, so I figured we needed to have a guy on staff who at least had an idea of what was going on, because it was definitely a different scene.” As it turned out, “that guy” already worked for Hadges, writing and producing his one-minute nightlife reports for WBCN. Oedipus had been very active in the two years since he’d been brought on board by Charles Laquidara, not making a whole lot of money but diving deeply into the city’s developing rock and roll culture. Oedipus explained,

There was a different kind of attitude; songs were passionate and intense. There was no possibility of sitting down to this music. We didn’t have time for all those guitar and drum solos! A scene developed with unique looks and black leather jackets. I’d be walking old Beacon Hill with the most intense purple or red hair you could imagine—just flaming! It’s nothing today, but back then, no one did it. Plus, I had these big red Elton John–kinda glasses. But it was supposed to be expressive. Just like the hippies with their long hair in the sixties and seventies, this was another statement: you stood apart.

I thought this music should be played [on the air], and it never would be on ’BCN. Tom Couch told me the MIT station, WTBS, accepted community volunteers to do programs, so I went down and volunteered—which I was certainly used to doing!

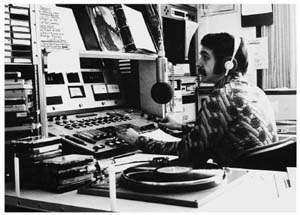

Tommy Hadges, WBCN’S new program director, at the Prudential Studios. Photo by Don Sanford.

The radio host welcomed nearly every important up-and-coming rock and roll band to WTBS’S sweltering basement studio: the Ramones, the Damned, the Jam, the Talking Heads, and dozens more. When a significant number of listeners mentioned Oedipus’s show, “The Demi-Monde,” in their Arbitron ratings responses, Tommy Hadges was mightily impressed; he quickly promoted the pink-haired punk into his own weekend overnight shift at WBCN. In 1998, Oedipus recounted the experience of his first show to Virtually Alternative magazine: “I was so nervous I stood the entire shift. I started with Willie Alexander, segued into the Clash, and played punk rock all night long. To my amazement, they didn’t fire me, which is what I expected. That was going to be my statement. Instead they kept me on midnight to six.”

Hadges’s next mission was to convince his old friend, Charles Laquidara, to return to WBCN after nearly two years in exile. The ex-DJ’S attitude typified the very rebellion that had fueled ’BCN’S presence in the past, and his zaniness inspired a spirit of weirdness and humor that always made the station anything but ordinary. “I went to drag him back,” Hadges chuckled. Laquidara, on a steady diet of cocaine, isolation in the woody Massachusetts suburb of Stowe, and deepening introversion, put up stiff resistance. “He was completely happy; it was quite an emotional thing to convince him that he was wasting his life away.” But Hadges finally prevailed on Laquidara to, at least, meet with Klee Dobra to discuss the idea.

“We were all in a room together,” Laquidara recalled, “and I was not serious about coming back. So, I just started throwing out these outrageous numbers . . . and they kept saying ‘yes.’ Then I went to the bathroom, did a couple sniffs of cocaine, came back and said, ‘It’s got to be tax-free!’ They offered me a tremendous amount of money, and I said, ‘My ratings weren’t even that good before I left.’ And Tommy said, ‘Yeah, but you’re a motivator; the station is just dying. We need some pizzazz, and you can do that.’” Laquidara signed back on once Hadges and Dobra agreed to his additional demands: “I got a contract they couldn’t break: I asked for eight weeks [of] vacation; I said, ‘No military ads.’ I also said I didn’t want to use my real name. I had such a great last show; I didn’t want to keep coming back.” So, Charles Laquidara returned to the air waves of ’BCN at the end of ’77, doing a weekend show as Charles Faux Pas Bidet. “That only lasted two days; I changed it to Lowell Pinkham, a guy in my school.” Still, the ideal pseudonym eluded him. Laquidara mentioned the nerdy Pinkham to a friend of his, who responded, “We had a guy like that; his name was Duane Glasscock.” Charles loved it. “But I needed something in the middle. D.I.G. . . . dig? Duane Ingalls Glasscock! That was it! He’ll talk with a Boston accent and be a guy that exposes all the hypocrisies around him.” Laquidara lurked behind his new character much like he’d hidden himself behind the mounds of coke. Eventually, though, enough of the old self-assurance returned that he was persuaded to return to weekday mornings as himself, and D.I.G. was put on a shelf.

However, Duane would rise again. The mysterious alter ego, known as Laquidara’s teenage “Six Dollar Clone” (as opposed to the “Six Million Dollar Man”), allowed the DJ to indulge his passion for acting, Duane emerging for the occasional fill-in show and a more frequent Saturday midday shift. WBCN’S future music director and producer Marc Miller attested, “He would not respond to the name Charles on Saturdays, only the name Duane. That was really nuts!” Glasscock was destined to be fired several times but, like a cockroach, always popped up again, shouting his trademark “Hello, Rangoon!” to announce each return. Even though the shows were organized affairs with prerecorded bits and routines from ’BCN’S inventive production staff, Duane’s ad-lib style and ADHD personality, along with his (supposed) amateur ability, resulted in a true free-form pandemonium. Duane traveled to places that even his extroverted alter ego wouldn’t touch; and the show always championed some specific cause or goal, like ousting Mayor Kevin White from office, giving away a dinner with the Stones (not the band, but a local couple), or taking over ’BCN to force management’s hand in giving the clone more radio time.

In one memorable Duane segment, the excitable host became agitated with Arbitron, as Charlie Kendall, who would replace Tommy Hadges in the program director chair, recalled: “Duane got on the radio and said, ‘We just got the ratings back and they say we have no listeners! Let’s prove to them we do. I want you all to send a bag of shit to Arbitron!’ I was listening and I go, ‘Did he just say that?’ Yes he did! And he said it again and again.”

“Duane told them, ‘Make sure you put it in plastic bags because you don’t want the postman knowing,’” Laquidara clarified (referring to himself in third person). “He gave out the exact address of Arbitron in Beltsville, Maryland, every fifteen minutes.”

“About two, three days later, I get a call from a friend of mine who works at Arbitron,” Kendall resumed. “He said that they had gotten 14 bags of shit [in the mail] and would I happen to know anything about it. I said, ‘Uh, gee, no.’ He said, ‘Look, you’ve got to stop this from happening anymore.’ So, I had to tell the general manager.” Laquidara recalled,

Monday came and I was doing my show. Klee Dobra popped open the studio door and said, “I’d like to see you after your show.” So I went to his office and he was sitting in there with this huge cup of steaming coffee, and he was stirring it with his finger! “Uh-oh.”

He said, “Charles is the consummate radio announcer; he is a professional. But Duane Glasscock is a FUCKING IDIOT! And he’s fucking over! He’s never to step foot in this station again! If we lose our license over that asshole, there’s going to be hell to pay!”

“Klee, you can’t do that. Duane has huge ratings; he has a huge cult following . . .”

“Stop! You’re talking about him like he’s another person!”

“But you just fired him, and kept me!” Anyway, Duane was blown off the air for three or four weeks, but by popular demand, he was back.

Duane Ingalls Glasscock, the Six Dollar Clone, would eventually die, but it didn’t happen until 1989. A D.I.G. official armband of mourning. From author’s collection.

With Charles on board again and the bespectacled Oedipus rocking out, Tommy Hadges’s third major hire, in March 1978, was David Bieber, the promotional maestro who had occasionally worked with WBCN as a freelancer in the past. “’BCN never had any budget or money for marketing and advertising,” Bieber said. “But Tommy and Klee convinced Mitch Hastings that it was opportune to have a kind of resurgence.” With an actual budget in his hand, the new hire began flooding the local, mostly print, media with WBCN’S presence. He not only created ads that focused attention on the heritage that the station had justifiably earned but also heightened awareness of the rebuilt and recharged jock lineup. The station now began to grapple with its radio rival in earnest. Instead of being locked into the self-absorption that had crippled it earlier, ’BCN now understood the politics and practices of competition and how to do “underground radio” in the brave, new world around it.

But as Boston dug itself out from the “Blizzard of ’78,” and even before Bieber had settled into his new office, Tommy Hadges arrived at a difficult decision: he would accept the offer he’d received to join WCOZ as its program director. At the same time, quite independently, ’COZ’S afternoon drive personality Mark Parenteau decided he needed to move on, too. While Hadges desired the professional surroundings of Blair Broadcasting, “a more respected company,” as he put it, Parenteau had grown to hate the place: “WCOZ had a corporate mindset, not at all like where I was in Detroit, which was a hippie station like ’BCN. Tight playlist . . . I had to sneak records in. You couldn’t even touch the records either; they had union engineers. You were at a desk with a microphone and a phone; that was it.” Parenteau met secretly with Klee Dobra at the Top of the Hub restaurant and cut a deal while Hadges worked on his own arrangements. Then, as in some Cold War exchange between East and West, the two left their respective jobs on the very same day, passing each other on their chosen paths like two captured spies swapped by their respective governments.

WBCN’S newest addition had been introduced to radio at a very early age in Worcester, thanks to his mother, who was part of an afternoon women’s talk show on WAAB. He’d stop by the station on the way home from school and inevitably be invited into the on-air conversation. “They’d put the big boom microphone on me, and they loved me because I would just talk. There was no stopping me; I’d just go on and on.” As Parenteau got older, he hosted his own record hops on Friday nights at the Bethany Congregational Church, which catapulted him onto Worcester’s premier Top 40 teen station, WORC-AM, when he was only fifteen. “I became Scotty Wainwright on the air; I was a sophomore in high school making a ton of money. I’d be on from 10:00 p.m. to 2:00 in the morning. My mother would pick me up and take me home; I’d get some sleep and be in school at 7:30. The kids that had gone to sleep listening to me were now sitting next to me in school.” By eighteen, Parenteau as Wainwright, was living in Boston and taking the commuter rail to his new gig at WLLH in Lowell. When he attended the infamous Alternative Media Conference in Vermont early in 1970, connecting with some Detroit radio movers and shakers, it led to a successful stint on FM rockers WKNR and then WABX before he returned to Boston as a seasoned veteran nearly six years later. “But I always wanted to be at ’BCN . . . the great station.”

With the departure (again) of Steven “Clean,” Matt Siegel (displaced and a bit unsettled by Laquidara’s return) ended up in afternoons for a short time. New arrival Mark Parenteau grabbed the evening shift, and Tracy Roach took middays. When Klee Dobra brought in radio veteran Charlie Kendall to be operations manager (a program director with some expanded responsibilities), the team, befuddled by the defection of their boss and friend Tommy Hadges, now had an experienced programmer at the helm.

“The thing about ’BCN was that the attitude was so counterculture that it was hard to get them to focus on the fact that it was a business and we needed to be entertaining,” Kendall pointed out. “I had to instill the will to win in that staff and give them a few tricks on how to do that: getting in and out of a break and how to relate to the audience in some way other than simply being self-focused and self-serving. I introduced a thing called center-staging: ‘As long as every other song is by an artist that can fill up the Boston Garden, we’re going to win.’” Matt Siegel didn’t think the new restrictions were a big deal at all. He chuckled, “When you talk about Kendall tightening things up, it was like telling your kids, ‘You really have to be in by 4:00 a.m. on school nights!’”

But not everyone agreed with Siegel. “Kendall was really a formatted radio guy; he didn’t have any sympathies for what we were doing,” Jim Parry charged. “It definitely tightened up a lot and became a very different station.”

“Charlie Kendall didn’t really like me on the air; his was more of the slick school of progressive rock radio,” assessed Sam Kopper. In other words, Kendall understood and felt affinity with the WCOZ way of doing things: quick breaks, smooth DJ delivery, and tighter playlists. Kopper, who was driving his “Crab Louie” recording bus all around the East Coast to engineer as many as three live broadcasts a week for several radio stations, took the hint: “He wanted me to leave, and I was so busy anyway, we decided I would resign at the end of 1978.” Kopper got a bigger bus, stuffed it with recording gear, renamed his company “Starfleet,” and went on to continued success. In his defense, Kendall stated, “There were some who didn’t like me, but it’s what had to be done, or the place would have become a parking lot.”

In May 1978, not happy with the energy level of the station, Kendall sought out a music director with a harder rock and roll edge to replace John Brodey, whose tastes ran more toward R & B, reggae, and soft rock. The DJ, operating on the air under the moniker of “John Brodey, John Brodey” in honor of the popular television sitcom “Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman,” kept his air shifts but would only hang around till early ’79, when he left for a job at Casablanca Records (promoting the dance music he loved but also, ironically, the primal thump of Kiss). Kendall filled the vacant slot with Tony Berardini, whom he found at San Rafael’s KTIM-FM. “All Tony wanted to be was a DJ; I said, ‘No, no, no, you’re the music director; I need someone who rocks!” Nevertheless, he promised Berardini a radio show, and the new recruit packed up his beloved VW bus and drove east. “My first three songs on the air at ’BCN were AC/DC’S “It’s a Long Way to the Top,” Van Halen’s “Ain’t Talkin’ ’Bout Love,” and “California Man” by Cheap Trick. I figured that was a good sampling of where I was coming from musically!” Tony Berardini would began his WBCN career with no more aspirations than enjoying his next radio show and organizing the station’s music, but he’d soon be thrust into greater roles, desired or not, to eventually become one of the station’s principal sculptors for a great portion of its history.

California governor Jerry Brown visits WBCN. (From left) Tony Berardini, Oedipus, Brown, Tracy Roach, Danny Schechter, and Lorraine Ballard. Photo by Eli Sherer.

Then, Charlie Kendall took a sobering look at the news department and slashed the daily newscasts: “They were running ten, fifteen minutes long, all day long!” When he did that, “everybody got upset,” Kendall recalled.

“News was reduced in size and importance,” Schechter pointed out. “The consequence was that an important part of the character of the station began to be lost: that we were concerned with issues, engaged with the community, and giving airtime to people who were advocates of change. As the airtime went away, those people would go away.” Kendall was not entirely unsympathetic; out of this developed WBCN’S long-standing news and entertainment show called the “Boston Sunday Review.” Sue Sprecher, hired as a reporter into the news department from the University of Wisconsin in 1976, liked Kendall’s idea: “The station’s other public affairs programs had become rather tired and almost cliché; there was a gay show, a women’s show, a black show, [and] Mackie MacLeod did the prison show. I can see why Charlie, as a programmer, would take all this time and put it into Sunday morning.”

“Danny told me, ‘I like that. It can work,’” Kendall explained. “That got him off my back.” Schechter, for his part, didn’t remember being as agreeable to the idea and saw the show as a bittersweet compromise, but the “News Dissector” would be gratified to witness the “Boston Sunday Review” win the Boston Globe Reader’s Poll as best radio talk show in the city and gain high Arbitron ratings for its time slot. A testament to its enduring strength and popularity, the “Boston Sunday Review” would continue to thrive, past the departures of Sue Sprecher and Danny Schechter in the forthcoming decade, to live on, even beyond the long-distant demise of its parent radio station.